Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Young animals

The generic name is a corruption of arawata, the Carib name of the Venezuelan red howler monkey (A. seniculus). The specific name is derived from the Latin pallium, a large cloak, worn by Greek philosophers. In this case, it refers to the tuft of long hairs on the sides of this animal.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek ateleia (‘incomplete’ or ‘imperfect’), alluding to the reduced or non-existent thumbs of these monkeys. The specific name was given in honour of French naturalist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1772-1844), who participated in an expedition to Egypt 1798-1801.

The springbok lives in dry areas of south-western Africa, from extreme southern Angola southwards through Namibia and western Botswana to western South Africa. It is the national animal of the latter country.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek anti (‘opposite’) and dorkas (‘gazelle’), indicating that this animal is not a true gazelle, and the specific name is derived from the Latin marsupium (‘pocket’), alluding to the skin flap.

In differs from the true gazelles by having horns that are straight, or with the tips curving slightly forward, whereas those of the true gazelles are usually curving backward in an arch. (However, see Nanger granti below.)

The yak was domesticated by nomadic tribes as early as c. 5000 B.C., and today the population is estimated at 14 million, the vast majority in Chinese territories. The population of wild yak may be fewer than 15,000, and though it is legally protected, illegal hunting still takes place and may threaten this magnificent animal with extinction.

The generic name is the classical Latin term for oxen, derived from Ancient Greek bous (‘ox’). The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘grunting’ – a most descriptive name, as yaks grunt incessantly.

A Nepalese legend, relating how the yak got its rich fur, is found on the page Animals – Animals as servants of man: Water buffalo.

Domestication of the eastern subspecies of the aurochs, ssp. namadicus, took place about 6,000 B.C. in the Indus Valley. These domesticated animals evolved into today’s zebu, with its characteristic hump. From the Indus Valley, this breed was brought to practically all warmer areas of Asia, including China, Southeast Asia, and Indonesia. Around 2,000 B.C., it arrived in Africa. Today, it is also found in tropical areas of the Americas. (Source: Ajmone-Marsan et al. 2010)

The specific name is the classical Latin term for a bull, originating from Proto-Indo-European tawros (‘bull’).

Many pictures, depicting cattle, are shown on the page Animals: Animals as servants of man.

The name nilgai is Hindi, meaning ‘blue cow’, which refers to the slate-coloured, slightly bluish coat of the male, and to its similarity to the sacred cow. For the latter reason, the nilgai is protected by devout Hindus and has thus escaped the fate of many other animals in India, which are on the brink of extinction, such as the tiger (Panthera tigris), the lion (Panthera leo), and the blackbuck (Antilope cervicapra). The coat of females and young animals is a pale sandy brown. Both sexes have a white throat patch.

The scientific name of this antelope is quite peculiar. It is derived from four Greek words, bous (‘cow’), elaphos (‘deer’), tragos (‘goat’), and kamelos (‘camel’). The name was applied by Prussian naturalist Peter Simon Pallas (1741-1811), to whom this antelope apparently resembled a mixture of these four animals.

The main difference between the two lies in the shape of the horns, which in the wild species are massive, spreading out sideways almost horizontally, only curving at the tip, whereas the horns of the domestic animals are smaller, curved almost from the base.

Traditionally, the water buffaloes, which live in the wild in several national parks in Sri Lanka, were regarded as wild buffaloes, but in all probability they descended from feral domestic buffaloes, as their horns are smaller than those of the genuine wild water buffaloes in Assam.

The generic and specific names are a Latinized version of Ancient Greek boubalos, the classical word for buffaloes.

The water buffalo is described in depth on the page Animals: Animals as servants of man.

The domestic goat is still closely related to the Bezoar goat, which is named ssp. aegagrus, to distinguish it from the domestic goat, ssp. hircus.

A male goat is called a billy, or a buck, whereas a castrated male is a wether (like a castrated sheep). A female goat is a nanny or a doe. Young goats are called kids.

Over time, goats, similar to sheep (Ovies aries, below), have been spread to most areas of the globe. Its total worldwide population is estimated at one billion, about half of which are in Asia.

It is almost unbelievable, what goats are able to digest – bone-dry grass, thorny twigs, cardboard boxes. Indeed, in northern India, I once watched a herd of goat head straight for a growth of very poisonous thorn-apples (Datura stramonium) and commence eating the fruits. Apparently, goat stomachs can neutralize the toxins.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for a she-goat. A billy-goat was called caper. The specific name a Latinized version of Ancient Greek aigagros (‘wild goat’). The subspecific name is another classical Latin term for a billy-goat.

In summer, the alpine ibex lives in rocky areas just below the snow line, at elevations between 1,800 and 3,300 m, descending to lower altitudes in the winter.

The specific name is the classical Latin term for the chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra). Its origin is unknown. Why it was applied to this goat is not clear.

The blue wildebeest, also known as brindled gnu, is distributed from southern Kenya southwards through eastern Africa to central Zambia, and from southern Angola and Zambia southwards to South Africa and Mozambique. The specific name means ‘bull-like’, derived from the Greek tauros (‘bull’), whereas the prefix blue refers to the bluish sheen of the coat.

Five subspecies are recognized:

The nominate blue wildebeest (ssp. taurinus) is widely distributed in southern Africa, from southern Angola and south-western Zambia southwards to central South Africa and southern Mozambique.

Cookson’s wildebeest (cooksoni) is restricted to the Luangwa Valley, Zambia.

The black-bearded wildebeest (johnstoni), also called Nyasaland wildebeest, occurs from central Tanzania southwards to northern Mozambique. It is extinct in Malawi (formerly called Nyasaland).

The eastern white-bearded wildebeest (albojubatus) lives in southern Kenya and northern Tanzania, east of the Rift Valley.

The western white-bearded wildebeest (mearnsi) is found in southern Kenya and northern Tanzania, west of the Rift Valley, westwards to Lake Victoria. This subspecies undertakes a spectacular annual migration, where 2 or 3 million wildebeest migrate from the Serengeti Plains northwards to southern Kenya, and later vice versa.

The pictures below all depict white-bearded wildebeest, subspecies mearnsi.

The generic and specific names may stem from a Wolof word, koba, used for the roan antelope (Hippotragus equinus).

These antelope live in marshy areas, feeding on aquatic plants. Their legs are covered in a water-repellant substance, which allows them to run quite fast in water, and thus having a greater chance of escaping from predators.

The red lechwe, subspecies leche, is widely distributed in wetlands of northern Botswana, north-eastern Namibia, and south-western Zambia. A core area is the Okavango Delta in Botswana.

The Kafue Flats lechwe, subspecies kafuensis, is restricted to a small area in the Kafue Flats, a seasonally inundated flood-plain on the Kafue River, south-western Zambia. It is listed on the IUCN Red List as vulnerable.

The black lechwe, subspecies smithemani, is confined to the Bangweulu Basin, northern Zambia. In former times, hundreds of thousands of these antelopes roamed the grasslands in this area, but their numbers have shrunk drastically due to uncontrolled hunting, and today there may be as few as 30,000. Only the adult male is blackish, whereas females and young are various shades of brown. Following the rainy season, when the water recedes from the flooded areas around the Bangweulu Swamps, fresh grass sprouts, and large numbers of black lechwe frequent these areas to graze.

A fourth subspecies, robertsi, called Roberts’ lechwe or Kawambwa lechwe, is now extinct. It was previously found in north-eastern Zambia.

The specific name may stem from a Sotho word, letsa, meaning ‘antelope’.

This species was described in 1878 by Anglo-Irish naturalist Sir Victor Alexander Brooke (1843-1891). The generic name is from the Greek lithos (‘stone’) and the Latin cranium (‘skull’). Apparently, the gerenuk has a hard skull. The specific name was given in honour of English naturalist Richard Waller (c. 1655-1715), whereas the common name derives from a Somali word, garanuug, meaning ‘giraffe-necked’.

Two subspecies are identified, northern gerenuk or Sclater’s gazelle, ssp. sclateri, which is found from eastern Ethiopia and Djibouti southwards to north-western Somalia, and southern gerenuk or Waller’s gazelle, ssp. walleri, which is distributed from central Somalia southwards to north-eastern Tanzania. Sclater’s gazelle was named for English lawyer and zoologist Philip Lutley Sclater (1829-1913).

Five subspecies have been described, distributed from South Sudan and Ethiopia southwards through Kenya to northern Tanzania. The male has thick horns that curve backwards and outwards, whereas the female has slender, usually straight horns, with the tip pointing slightly forward. In this respect, they resemble those of the springbok (above).

The generic name is a local Senegalese name for the dama gazelle (Gazella dama).

Formerly, it was placed in the genus Hemitragus, together with the Himalayan tahr (above) and the Arabian tahr (H. jayakari, today called Arabitragus jayakari). However, genetic research has shown that it is more closely related to sheep of the genus Ovis than to the other tahrs, and, consequently, it was moved to a separate genus.

The last part of the generic name is derived from Ancient Greek tragos (‘goat’), thus ‘the goat from the Nilgiri Hills’. The specific name is likewise from Ancient Greek, from hyle (‘forest’) and Krios, one of the Titans, son of Uranus and Gaia.

The domestic sheep is described in depth on the page Animals: Animals as servants of Man.

The generic name is the classical Latin term for sheep, the specific name for a ram.

The adult ram is a splendid animal, weighing up to 75 kilos, with thick, sweeping horns that may grow to a length of 80 cm. The coat is grey with a bluish sheen (hence its English name), with black markings on chest, flanks, and legs. Ewes and young males are more uniformly grey. The horns of females are small, growing to 20 cm long.

This species is widely distributed in Central Asia, from Ladakh, the northern Himalaya, and the Yunnan Province northwards across Tibet to Gansu, Ningxia, and Inner Mongolia. The Helan Mountains of Ningxia have the highest concentration of bharal in the world, with a population of about 30,000. It is also quite common in parts of the Himalaya, including Ladakh, Dolpo, and the border area between Nepal and Sikkim.

Bharal is the Hindi name of this animal, whereas the Nepali name naur has given rise to the specific name. The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek pseudes (‘false’) and ois (‘sheep’), alluding to the fact that the animal is sheep-like, but also has traits from goats.

The bharal was the main focus of an expedition to the Dolpo area of Nepal in 1973, led by German-American zoologist George Schaller (born 1933). He was accompanied by the famous American writer and environmentalist Peter Matthiessen (1927-2014). Their personal experiences are well documented in Schaller’s book Stones of Silence: Journeys in the Himalaya (1980), and Matthiessen’s The Snow Leopard (1978).

This species is distributed across the Sahel zone of central Africa, from Senegal eastwards to Ethiopia, and thence southwards to southern Tanzania. It was first described in 1767 by Prussian naturalist Peter Simon Pallas (1741-1811). Five subspecies are presently recognized.

The generic and specific names are Latin, meaning ‘bent backwards’, derived from uncus (‘hook’). This is odd, as the horns of these animals point forward.

These horns have given rise all names of this animal. The generic name is from the Greek tetra (‘four’) and keras (‘horn’), whereas the specific name is from the Latin quattuor (‘four’) and cornu (‘horn’). The Hindi name chowsingha is derived from chaar (‘four’) and siing (‘horn’).

Three subspecies have been described, quadricornis, which is distributed in most of the Indian Peninsula, subquadricornutus, which is found in southern India, and iodes, which is restricted to southern Nepal.

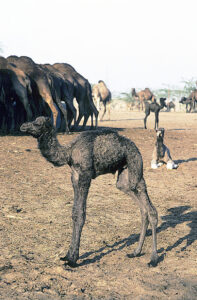

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kamelos (‘camel’), originating from Arabic jamal or Hebrew gamal. The specific name is Latin, derived from Ancient Greek dromos (‘race course’), thus ‘racing camel’. From ancient times, camel races have been popular.

Under all circumstances, the archaeological evidence shows that the wolves, which were domesticated by hunter-gatherers, were the first domesticated animal species of all. This domestication took place at different localities simultaneously, probably in Western Europe, Central Asia, and East Asia.

The complicated ancestry of the dog is described on the page Animals: Animals as servants of Man.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for dog, the specifc name for wolf.

Hunting dogs live in packs, the size of which varies enormously, from 2 to about 25 members – usually between 6 and 10. Most of the year, these animals are nomads, roaming savannas and woodland in search of prey. The hunting area of a pack may exceed 4,000 km2.

As a rule, a bitch gives birth to 8 to 16 pups. She only has 12 or 14 teats, and if the litter is larger the pups must suckle in turn. Under normal circumstances, the other dogs in the pack have no difficulty in supplying enough food for the mother and her pups. During his studies, biologist Hugo van Lawick noticed a peculiar behaviour, when he watched a dominant female suckling a mother dog of a lower status (H. Lawick & J. Goodall 1970. Innocent killers. Collins). The desire for suckling seems to be quite strong.

Formerly, the African hunting dog was distributed throughout sub-Saharan Africa but has disappeared from much of its former range. This decline is due to habitat fragmentation, persecution from humans, and a very contagious viral disease, which has killed entire packs all across East Africa. In 2016, the total population was estimated at about 6,600 adults, of which only c. 1,400 were reproducing, in 39 subpopulations (IUCN).

The species is still fairly common in Botswana and Zimbabwe, and it may be able to spread northwards from here. Hopefully, these fascinating nomads will continue to roam the African savannas in the future.

My encounters with the African hunting dog are described on the page Animals – Mammals: Hunting dogs – nomads of the savanna.

Red foxes live in pairs or small family groups, in which young from a previous litter assist in bringing up the next litter. They are quite omnivorous, their food consisting of rodents, rabbits, young deer, birds, reptiles, invertebrates, fruit, and sometimes also green plants. In areas with wolves, coyotes, golden jackals, or large cats, the red fox is very vulnerable to attacks from these larger predators.

The red fox has been extensively persecuted by humans for thousands of years. Initially, it was hunted for its rich fur, but when humans settled as farmers and began raising fowl, the fox quickly began killing the fowl. For this reason, it was persecuted as a pest. In later years, it has successfully spread to urban areas, where no hunting takes place. Here they thrive, feeding on rodents and edible garbage. Many people also feed them.

The generic and specific names are the classical Latin word for fox.

The generic name originates from the Brazilian Tupi word sauja, a term used for a species of spiny rat, Makalata armata. In Old Portuguese, this was corrupted to çavia.

The specific name is Latin, a diminutive of porcus (‘pig’), thus ‘little pig’, alluding to its somewhat pig-like shape. The common name is rather odd, as the animal never lived in Guinea.

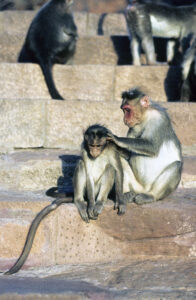

The vervet, as of today, is distributed from Ethiopia and southern Somalia southwards through Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Mozambique, and Botswana to South Africa. It lives mainly in savanna and open woodland, almost always near rivers, but is extremely adaptable and able to survive in cultivated areas, and sometimes in towns. There are no major threats to this species, although many are shot in agricultural areas, where they do damage to crops. It is also hunted as bushmeat in some areas.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek khloros (‘green’) and kepos, a type of long-tailed monkey. The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek pyge (‘rump’) and erythros (‘red’), alluding to the rump having a reddish tinge.

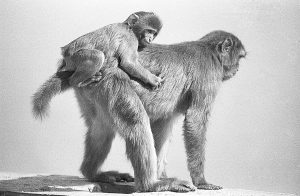

Taiwan macaque occurs from sea level to c. 3,600 m altitude, but is most common between 1,000 and 1,500 m. There are no major threats to the species.

The generic name stems from the word makaku, plural of kaku, a West African Bantu name for a species of mangabey. In Portuguese, makaku became macaco, and in French macaque, the latter adopted by the British. In 1798, French taxonomist Bernard Germain de Lacépède (1756-1825) applied this word of African origin, in the form Macaca, to an almost exclusively Asian group of monkeys, presumably because he was familiar with the Barbary macaque (Macaca sylvanus, below) – the only species of the group outside Asia, living in north-western Africa and on the Rock of Gibraltar, southern Spain. (Source: itre.cis.upenn.edu/~myl/languagelog/archives/003458.html)

The specific name refers to the cyclops, a one-eyed giant from the Greek mythology. Why the name was applied to this monkey is hard to see.

The long-tailed macaque lives in a wide range of habitats, including mangrove, forests, agricultural areas near forest, and temple groves. In the Philippines, it is found at elevations up to 1,800 m, in Indonesia up to 1,000 m, and in Thailand up to 700 m, whereas in Cambodia and Vietnam it generally occurs below 300 m. In the Philippines, some populations are threatened by hunting.

It is rather puzzling, why Sir Thomas Raffles (1781-1826), Lieutenant-Governor of British Java 1811-1815, and Governor-General of Bencoolen (on Sumatra) 1817-1822, applied the specific name fascicularis (‘with a small band or stripe’) to this species, as it does not have any stripes.

The following pictures are all from the so-called ‘Monkey Forest’ in Ubud, Bali, Indonesia, a forested area around the Hindu temple Wenara Wana, which is home to several troops of these monkeys.

Its fur is mainly brown, with yellowish-orange hind parts, and the tail is rather short, 20-30 cm. This monkey lives in very diverse habitats, from semi-desert via various forest types to temple groves and cities, from the lowland up to altitudes around 2,500 m.

Following a strong decline due to felling of forest, combined with export of many animals for medical research, the rhesus monkey is now expanding in India, with an estimated population of 500,000 individuals, or more. This expansion is mainly due to the fact that it has adapted to a life in cities.

The size of a territory of a typical troop of rhesus monkeys has been measured at up to 16 km2 in montane forest, and 1-3 km2 in other types of forest, whereas in Kolkata, a troop of 62 individuals was studied, thriving successfully in an area of less than 4 hectares, in the centre of this metropolis.

In some areas, especially in Laos and Vietnam, the species is hunted for food, and habitat destruction has also affected populations locally in Indochina.

In the great Hindu epic Ramayana, the monkey army, led by Hanuman, plays a significant role, and for this reason monkeys are regarded as sacred animals among devout Hindus. Troops of rhesus monkeys, bonnet macaques (below), and northern plains langurs (below) often live around temples, where part of their diet consists of rice, sweets, or other edibles, brought as offerings to the gods.

Examples of such temples are Pashupatinath, a Hindu temple on the shores of the Bagmati River, Kathmandu, the Manakamana Kali Temple in central Nepal, the great Buddhist stupa Swayambhunath in Kathmandu, which also contains Hindu shrines, and the Buddhist temple atop Mount Popa, Myanmar.

In the West, the rhesus monkey has become well-known due to its usage in medical research, which detected the rhesus factor, an inherited antigen in the blood of humans.

The specific name is of unknown origin. The common name may refer to a person in Greek mythology, King Rhesus of Thrace, who sided with the Trojans during the Trojan War, related in the Iliad.

It is very common, locally abundant, living in all forest types, scrubland, plantations, agricultural lands, and urban areas. It is usually found below 2,000 m altitude, occasionally up to 2,600 m. As it often feeds in agricultural areas, conflicts with humans is an increasing problem. It is locally hunted, and many are caught for research, as well as for street performing.

Whereas the temple monkeys in northern India are mainly rhesus monkeys, this role is taken over by bonnet macaques in southern Indian temples.

It lives in a variety of forest types, from sea level up to about 2,100 m. The distribution areas of all three subspecies are very fragmented, and opisthomelas is restricted to an area of less than 500 km2, with only a fifth of this area actually occupied by the animals. The chief threat to this species is habitat loss due to establishment of plantations and agricultural lands. Many are shot, as they are doing considerable damage to crops.

The toque macaque is still widely distributed, but the population may have declined by more than 50% since 1975.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘from China’. When Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) named the species in 1771, he must have been misinformed about the origin of it. The common name is a kind of hat without brim.

Recently, the Moroccan population was estimated at 6,000 to 10,000 individuals, whereas in 1975 it was about 17,000. In Algeria, around 1980, the population was estimated at 5,500, but the present number is unknown. The total population may have declined by more than 50% since 1980, and the decline is expected to continue. All areas occupied by the Barbary macaque are under growing pressure from human activities.

There is also a small population of about 300 animals on the Rock of Gibraltar, southern Spain, which may, at least in part, be a remnant of the former European population. Historical sources, however, mention repeated release of African animals on the rock.

In his work from about 1610, Historia de la Muy Noble y Más Leal Ciudad de Gibraltar (’History of the Very Noble and Most Loyal City of Gibraltar’), Alonso Hernández del Portillo writes, “But now let us speak of other and living producers, which in spite of the asperity of the rock still maintain themselves in the mountain; there are monkeys, who may be called the true owners, with possession from time immemorial, always tenacious of the dominion, living for the most part on the eastern side in high and inaccessible chasms.” (Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barbary_macaques_in_Gibraltar)

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘living in forests’, derived from silva (‘forest’) and the suffix anus, meaning ‘from’ or ‘of the’.

It is very adaptable and is able to survive in secondary forest and cultivated areas. Despite being considered a pest, which is trapped, shot, and poisoned in places, it is still locally common.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for baboons. The specific name refers to Anubis, the Egyptian god of embalming, who had the head of a jackal. Baboons have dog-like muzzles.

It is quite common, living in a variety of habitats, including forests, scrubland, temple groves, gardens, and towns, up to an altitude of c. 1,700 m. It is locally threatened by habitat loss due to intensified agriculture and fires, and by hunting for food by newly settled people in Andhra Pradesh and Orissa.

Previously, western and southern populations of this species were regarded as a separate species, the southern plains langur (S. dussumieri), but recent genetic research has declared this name invalid.

The generic name is from Ancient Greek semnos (‘sacred’) and pithekos (‘monkey’), alluding to the sanctity of monkeys to Hindus (se Macaca mulatta above).

The specific name refers to an aged Trojan, mentioned in the poem The Aeneid, by Roman poet Publius Vergilius Maro (70-19 B.C.), also known as Virgil. The Aeneid relates the legendary story of Aeneas, a Trojan who fled after the fall of Troy to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Romans.

It is still widespread, but was much affected by droughts, which ravaged Ethiopia in the 1980s. From an estimated population of maybe 800,000 individuals, a present guesstimate says c. 200,000. Its habitat is being eroded as a result of agricultural expansion, as an increasing number of people are moving into the central highlands. In some areas, the grazing pressure is high, forcing the geladas to move to less productive grass slopes.

The generic name is from the Greek thero (‘beastly’) and pithekos (‘monkey’), alluding to the rather grotesque appearance of the male of this species. In Greek mythology, Thero was a fierce Naiad, nurse of the infant Ares, who later became god of courage and war, but also of civil order.

The specific name is the Amharic name of this monkey.

The size of this huge deer varies considerably according to subspecies and also availability of nutritious food. On average, an adult bull measures 2 m at the shoulder, the cow 1.4 m. Bulls may weigh almost up to a ton, although 380-700 kg is more common. Cows typically weigh 200-490 kg. Besides his enormous antlers, the bull is characterized by a large dewlap. Seven subspecies are recognized.

The generic and specific names probably stem from Proto-Germanic algiz, which was corrupted to alke in Ancient Greek, and in Norse elgur, which was shortened to elg in Danish and Norwegian, älg in Swedish.

A medium-sized deer, males may weigh up to 100 kg, whereas the females are much lighter.

The generic and specific names are Latin, referring to an Indian animal, mentioned by Roman philosopher and naturalist Pliny the Elder (c. 23-79 A.D.). The Hindi name chital is derived from Sanskrit citrala (‘spotted’).

From Ukraine and the northern flanks of the Caucasus, eastwards through the taiga zone to the Pacific Ocean, and also in Tibet, Korea, and Manchuria, this species is replaced by the Siberian roe deer (C. pygargus). Formerly, these deer were regarded as a single species, but today most authorities recognize them as separate species. The Siberian roe deer is larger, with longer, more branched antlers than the European roe deer.

In Roman Latin, the term capra, or caprea, usually indicates a billy goat, but with the diminutive suffix olus added, it means ‘small deer’. The name pygargus stems from Ancient Greek pygargos, from pyge (‘rump’) and argos (‘white’), alluding to the deer flashing the white hair on the rump when alarmed.

The weight of a stag is typically around 350 kg, although large specimens may weigh as much as 550 kg. Hinds are smaller, weighing 100-200 kg. Populations of this deer have declined substantially in most areas, mainly due to hunting and habitat destruction. It has been introduced to various countries around the world, including Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.

The generic name is the classical Latin term for deer. The common name is derived from Sanskrit sambara (‘deer’).

The generic name is derived from the Greek odous (‘tooth’) and koilos (‘hollow’), alluding to the fact that deer of this genus have hollow teeth.

The name mule deer refers to its rather large ears, reflected in the specific name, from the Greek hemionos (‘mule’). The two common names indicate the main differences between this species and the white-tailed deer (O. virginianus).

This deer differs from all other Indian species in that the antlers carry more than 3 tines, giving rise to the Hindi name barah singga, meaning ‘twelve-horned’. Mature stags usually have 10-14 tines, but up to 20 has been recorded.

Three subspecies have been described. The western nominate race has splayed hooves, an adaptation to live in flooded grasslands in the Indo-Gangetic plain. Today, a population of about 2,000 live in scattered locations in Uttar Pradesh, and about 2,200 in the Sukla Phanta Wildlife Reserve in western Nepal.

The eastern subspecies ranjitsinhi is restricted to the north-eastern state of Assam, where the population was as low as about 700 in 1978. Since then, numbers have been steadily rising due to conservation efforts. In 2016, it was estimated that about 1150 individuals were present in Kaziranga National Park. A few also live in Manas National Park and other protected areas.

The southern subspecies branderi differs from the other subspecies in having hard hooves, an adaptation to live in open forest with an understorey of grass. Formerly, it was restricted to Kanha National Park in Madhya Pradesh, where only about 750 individuals survive. Lately, it has been reintroduced to Satpura Tiger Reserve, likewise in Madhya Pradesh.

The generic name is a combination of two other genus names, Rusa, which means ‘deer’ in Malay, and Cervus (above).

The specific name commemorates French naturalist and explorer Alfred Duvaucel (1793-1824), who died in India, only 31 years old. Rumours had it that he was killed by a tiger.

The current range of the Asian elephant is highly fragmented. In 2008, IUCN listed it as endangered due to a 50% population decline over the past 60-75 years. The total population of wild Asian elephants may now be as low as 50,000, or maybe even lower, as this number is an estimate. Researchers believe that about half of the population lives in India. In Sri Lanka, their number is about 6,000 – half as many as in the 1800s. However, Sri Lanka still has the highest density of Asian elephants anywhere.

When bulls are in rut, secretions ooze from a gland on the side of their head, signifying a higher production of male hormones, a condition called musth. During musth, bulls are highly aggressive, and tamed elephants in musth have been known to kill their mahout (trainer), without any apparent reason.

The gestation period is almost two years. A new-born Asian elephant calf weighs about 100 kilos. Six years old, it weighs about a ton.

In former days, bulls with large tusks were the prime target of trophy hunters, and today such animals do not exist. Cows have much smaller tusks than bulls. In the Sri Lankan subspecies, maximus, only 10% of the bulls grow tusks, the cows none at all. This trend has been reinforced by poachers, who select the bulls with the largest tusks.

The Asian elephant was first tamed in the Indus Valley about 5,500 years ago. Since its taming, it has been much utilized by people to pull or carry heavy burdens. In the Hindu Khmer culture of Indochina, royalty and other prominent persons were riding on elephants, when they went on hunting trips to shoot tigers and other big game. Elephants were also much used in Khmer warfare, and during the British colonial wars in India in the 1800’s, elephants hauled heavy cannons to the battlefields.

Until recently, in India and Southeast Asia, elephants were much used in the timber industry to haul out tree trunks from hilly forests. This usage continues today on a small scale in areas, which cannot be entered by heavy vehicles.

In India and Sri Lanka, elaborately adorned elephants are much used in processions during religious festivals.

In some national parks of Asia, elephants are utilized in the tourist industry, carrying people on wildlife watching trips. The elephants move silently through the forest, and tourists can get very close to wild animals, as most of them have no fear of elephants.

The generic name is the classical Greek term for elephants.

The savanna elephant is the largest land animal on Earth, a normal bull weighing 5 to 6 tons, a cow around 3 tons. The heaviest elephant ever recorded was a bull, shot in Angola in 1955, which weighed 10 tons and stood more than 4 m tall across the shoulder. On average, a forest elephant weighs only about half as much as a savanna elephant.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek loxos (‘slanting’ or ‘crosswise’) and odous (‘tooth’).

The generic name is derived from Proto-Indo-European ekwos (‘horse’). The subspecific name is the classical Latin term for donkey.

The donkey is described in depth on the page Animals: Animals as servants of Man.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘wild’, originating from Proto-Italic. The subspecific name is possibly derived from Persian kaval, a term used for horses of lower quality.

Previously, plains zebras in Namibia were regarded as a distinct subspecies, antiquorum. However, recent studies have revealed that it is genetically identical to Burchell’s zebra, subspecies burchelli, which was once regarded as extinct. As subspecies burchelli was described prior to antiquorum, the former name takes precedence. Thus, the plains zebras of Namibia are now called E. quagga ssp. burchelli.

The specific name is derived from Afrikaans kwagga, which originated from Khoisan koaah, perhaps an imitation of its neighing.

By the 1930s, the Cape mountain zebra had been hunted to near extinction, and only about 100 individuals survived. Since then, strict conservation measures have had the effect that the population has increased to more than 2,700.

In 1998, the population of Hartmann’s mountain zebra was estimated at about 25,000 individuals, whereas recent estimates say around 33,000.

The specific name is the Portuguese term for zebras, originating from Galician-Portuguese enzebro, ezebra, or azebra (‘wild ass’).

This species mainly inhabits savanna, but is also found in various types of open forest. Four subspecies are currently recognized. The nominate jubatus occurs from Uganda and Kenya southwards through eastern and southern Africa to Namibia and South Africa. It has been exterminated in Zaire, Rwanda, and Burundi. The population is estimated at around 5,000 individuals.

Subspecies soemmeringii is restricted to north-eastern Africa, occurring in South Sudan, Ethiopia, and Eritrea.

With a total population estimated at less than 250 individuals, subspecies hecki is listed as critically endangered by the IUCN. It has a scattered occurrence of tiny populations in southern Algeria, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Benin.

Today, the Asiatic cheetah, subspecies venaticus, is confined to Iran. It is classified as critically endangered by the IUCN, as the total population in 2017 was estimated at fewer than 50 individuals, scattered over the central plateau of Iran. In former times, this subspecies was distributed from the Arabian Peninsula and Turkey eastwards to Central Asia and India.

By 2016, the total cheetah population was estimated at around 7,100 individuals in the wild. Its decline is caused by loss of habitat, poaching for the illegal pet trade, and conflict with humans.

The generic name is derived from the Greek akinitos (‘motionless’) and onyx (‘nail’ or ‘hoof’), thus ‘motionless nails’, referring to the fact that the cheetah, unlike other cats, is unable to retract its claws. The specific name is from the Latin iuba (‘mane’ or ‘crest’) and atus (‘like’), thus ‘having a mane-like crest’, referring to the long mane of cheetah kittens below the age of 3 months. This mane is a means of camouflage, when the kittens are left in dense cover by their mother, when she goes hunting. The name cheetah is derived from the Sanskrit citra, meaning ‘variegated’, ‘spotted’, or ‘speckled’.

The generic and specific names are both classical Latin terms for cat.

The lion is unique among cats due to the male’s mane, a large growth of hair around the neck and down the chest, and often a little way down the back. The mane makes a male lion look larger than he actually is, without the disadvantage of a larger weight, which would require more food. A large mane is a signal to other males that here comes a powerful animal that shouldn’t be challenged, even if the challenging male is in fact larger than his opponent, but has a smaller mane. The mane also gives some protection during fights among males, for instance when stray males attempt to take over a pride.

The lion is described in detail on the page Animals – Mammals: Lion – king of the savanna, and an unusual nightly encounter with lions is related on the page Travel episodes – Tanzania 1990: Lions in the camp.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek panther, referring to the black-coated leopards (P. pardus) of India, in English often called panther.

The tall and seemingly ungainly giraffe was once distributed throughout Africa, except in rainforest. However, it has diminished alarmingly, and today there may be less than 100,000 individuals.

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), only one species of giraffe exists, divided into nine subspecies, whereas other authorities recognize up to eight separate species.

The generic name was derived from the Arabic zarafah, ultimately from Persian sotorgavpalang (‘camel-ox-leopard’), whereas the specific name is derived from the Greek kamelos (‘camel’) and pardos (‘leopard’), and the Latin alis (‘resembling’), alluding to its camel-like shape and leopard-like pattern.

It is distributed from Ethiopia and Somalia southwards through eastern Africa to north-eastern South Africa, and from southern Zaire and Zambia westwards to Angola and northern Namibia.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek helos (‘marsh’) and gale (‘weasel’), alluding to its weasel-like appearance. However, the first part is not appropriate, as members of this genus often live in dry areas. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘very small’.

The generic and specific names stem from Marathi mungus (‘mongoose’). The common name refers to the dark vertical stripes on the side of the body.

The scientific name is derived from Ancient Greek hippos (‘horse’), potamos (‘river’), amfi (‘both sides’), and bios (‘life’), thus ‘the river horse that lives on both sides’, referring to the fact that hippos live in water as well as on dry land.

This word was later used by American physician and missionary Thomas Staughton Savage (1804-1880) and naturalist Jeffries Wyman (1814-1874), when they described the gorilla in 1847, calling it Troglodytes gorilla. (Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gorilla)

Previously, gorillas were regarded as belonging to a single species, Gorilla gorilla, but they have since been divided into two species, the western gorilla (Gorilla gorilla), with two subspecies, the lowland gorilla (gorilla) and the Cross River gorilla (diehli), and the eastern gorilla (Gorilla beringei), likewise with two subspecies, the mountain gorilla (beringei) and Grauer’s gorilla (graueri).

The western gorilla is found in Cameroun, Central African Republic, Gabon, and the Republic of Congo, with tiny populations in eastern Nigeria and northern Angola. The population of subspecies gorilla is probably around 250,000 individuals, whereas subspecies diehli is seriously endangered, counting only about 300 individuals. The population reduction of this species, in its widest sense, is predicted to exceed 80% by 2070, due to illegal hunting, disease (Ebola virus), and habitat loss.

The eastern gorilla lives in montane forests of eastern Zaire, north-western Rwanda, and south-western Uganda. This region has been subject to war and civil war for many decades, during which gorillas also fell victim. Subspecies beringei, which counts only about 900 individuals, is the only great ape that has increased in number lately, whereas subspecies graueri has been severely affected by human activities, most notably poaching for commercial trade of bushmeat. This illegal hunting has been facilitated by a proliferation of firearms from the various wars of this region. Previously estimated to number around 17,000 individuals, recent surveys show that Grauer’s Gorilla numbers have dropped to only about 3,800 individuals.

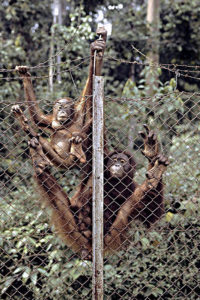

All three species are seriously endangered due to habitat destruction and fragmentation, and illegal poaching for zoos. It has been estimated that the population of the Bornean orangutan in 1973 was about 300,000 individuals, and it is assumed that this number will decline to c. 50,000 by 2025. The Sumatran orangutan has an estimated population of fewer than 14,000, and it is predicted that this number will decline by 80% by 2060. The population of Tapanuli orangutan is fewer than 800, and this number is still decreasing.

The generic name was erroneously applied to orangutans. It is the derived from the Kongo word mpongo, which means ‘gorilla’. The common name is Malay, meaning ‘forest people’.

In 1985, I visited the Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre in Sabah, Borneo. This centre is home to a number of orphaned orangutans, which were confiscated from poachers, who shot their mothers to get hold of the young. This centre, where the young ones are trained to a life in the wild, is presented in depth on the page Travel episodes – Borneo 1985: Visiting orangutans.

The spotted hyaena has a very complex social behaviour, with respect to group-size, hierarchical structure, and frequency of social interaction among both kin and unrelated group-mates. However, their social system is openly competitive rather than cooperative, with access to kills, mating opportunities, and the time of dispersal for males, all depending on the ability to dominate other clan-members. (Source: Holekamp, Sakai & Lundrigan, 2007. Social intelligence in the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, London, 362, pp. 523-538)

The generic and specific names are derived from Ancient Greek krokottas, which is described as an animal, being a mix of wolf and dog, native to Ethiopia.

Since its protection, the sea otter has made a dramatic comeback, and the total population may be as high as c. 110,000 individuals, with the most stable population, counting c. 27,000, living in Russia, notably on the Kuril Islands.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek en (‘in’) and hydra (‘water’), thus ‘living in the water’, and the specific name is Latin, meaning ‘otter’.

The Cape fur seal ranges along the southern coasts of Africa, from Ilha dos Tigres in southern Angola, along the Namibian coast to Algoa Bay in South Africa, whereas the Australian subspecies lives in south-eastern Australian waters, along the coasts of Tasmania, New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia, with the largest concentration in the Bass Strait.

The preferred breeding habitats of these seals are rocky islands, or pebble or boulder beaches. The population of the Cape fur seal is approximately 2 million, whereas that of the Australian fur seal is around 120,000. (Source: iucnredlist.org/details/2060/0)

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek arktos (‘bear’) and kephale (‘head’), thus ‘with a head like a bear’. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘small’.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek keras (‘horn’) and therion (‘beast’). The specific name is derived from the Greek simos (‘snub-nosed’), alluding to the square mouth of this species, an adaptation for grazing.

It has often been claimed that the most commonly used name, white rhino, is a mistranslation of the Dutch word wijd to the English word white. Wijd means ‘wide’ in English, and it was supposed to refer to the width of the rhinoceros’s mouth. However, this is not the case. In fact, the name white rhino can be traced back to a letter in Dutch, written by the Boer Petrus Borcherds to his father in 1802. In this letter, he mentions two rhinos, both killed in 1801, a male of the ‘black variety’, and a female ‘white’ rhino. Concerning the female, Borcherds stated (still in Dutch): “She was of the type known to us as the white rhinoceros. (…) I expected this animal to be entirely white, according to its name, but found that she was a paler ash-grey than the black male.” (Source: Jim Feely 2007. Black rhino, white rhino: what’s in a name? Pachyderm 43, pp. 111-115)

However, both species are in reality grey, the ‘black’ rhino somewhat darker than the ‘white’ rhino.

Both scientific names mean ‘two-horned’, the generic name derived from the Greek dyo (‘two’) and keras (‘horn’), the specific name from the Latin bis (‘twice’) and cornu (‘horned’). The last common name refers to the pointed lips of this species, an adaptation for browsing on bushes.

By far the largest colony is in the Janos Region of Chihuahua, where hundreds of thousands of animals survive, although their numbers are declining, mainly due to increasing cultivation of the area.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kynos (‘dog’) and mus (‘mouse’), thus ‘dog-mouse’, the first part of which refers to an old French term for these animals, petite chien (‘little dog’), alluding to one of their calls, which slightly resembles the barking of a dog.

The specific name, which is the Latin form of Ludwig or Louis, refers to Captain Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809) of the famous Lewis and Clark expedition 1804-1806, when this prairie dog was first collected for science.

This species and other prairie dogs are described in depth on the page Animals: Squirrels.

From a distance, this animal appears largely naked, seemingly only with a crest along the back, and tufts of hair on the cheeks and tail. At close quarters, however, you notice a cover of short, bristly hairs on the body. The male has prominent tusks that may sometimes reach a length of up to 60 cm, much smaller in the female.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek phakos (‘wart’) and khoiros (‘pig’), like the common name referring to the facial wattles of these animals, largest in the males.

I once had a close encounter with a wild boar, see Travel episodes – Iran 1973: Car breakdown at the Caspian Sea.

An amusing account of a wild boar hunt is related on the page Quotes on Nature, written by the famous hunter and conservationist Jim Corbett (1875-1955).

The generic name is the classical Latin word for hog. The specific name stems from Proto-Indo-European skreb (‘to scrape’), but in classical Latin it became the term for a sow.

The generic name is the classical Latin term for mole.

The drake is a gorgeous bird in breeding plumage, with grey sides, purple breast, and glossy-green head, with a blue shine from certain angles. The female is a uniform speckled brown. Pictures, depicting male and female, may be seen on the page Animals – Animals as servants of Man: Poultry.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for duck. The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek platys (‘flat’) and rhynkhos (‘bill’).

Over the last 50 years, the population has greatly increased due to protection from shooting on the wintering grounds. Numbers in Ireland and England have risen from about 30,000 in 1950 to about 300,000 today.

The pink-footed goose is closely related to the bean goose (A. fabalis) and was formerly treated as a subspecies of that species.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for goose. The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek brakhys (‘short’) and rhynkhos (‘snout’, ‘bill’), alluding to the rather short bill of the bird.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek kyknos (‘swan’) and the suffix oides (‘resembling’), referring to the similarity of the bill of this goose with the bill of mute swan (Cycnus olor).

The generic name is a Latinized form of brandgás (‘burnt goose’), the Old Norse name of the brent goose (Branta bernicla), referring to the mainly black plumage of this species. In English, ‘burnt’ became ‘brent’.

The scientific name is derived from Ancient Greek khloe (‘young green grass’), phagein (‘to eat’), polion (‘grey’), and kephale (‘head’).

This species has two disjunct breeding areas, from Eritrea southwards to Tanzania, and from Namibia and Zimbabwe southwards to the Cape Province.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek oxys (‘sharp’) and oura (‘tail’). The specific and common names can be traced back to the Boer, who apparently found that this duck resembled the domestic Muscovy duck, which, for some reason or other, they called makou. This was then corrupted to maccoa. In fact, the word makou is of Chinese origin, referring to the Portuguese enclave Macau.

Both scientific names, as well as one of the common names, refer to the bronze-coloured speculum of this bird, whereas the name spectacled was given in reference to the large white patch in front of the eye. Locally, it is known as pato perro (‘dog-duck’), alluding to the harsh, barking call of the female.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for herons. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘ash-coloured’.

Other pictures, depicting this bird, are shown on the pages Fishing, Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan, and Animals: Urban animal life.

Originally, this bird was native to southern Spain and Portugal, the northern half of Africa, and across the Middle East and the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to Japan, and thence southwards to northern and eastern Australia. In the late 1800s, it began expanding its range into southern Africa, and in 1877 it was observed in northern South America, having apparently flown across the Atlantic Ocean. By the 1930s, it had become established as a breeding bird in this area, rapidly spreading to North America, where it is now found as far north as southern Canada. In later years, it has also spread northwards in Europe.

As its name implies, it often follows cattle to snap grasshoppers and other small animals, flushed by the grazers. It is also often observed in newly ploughed fields. The generic name is Latin, meaning ‘cowherd’. The specific name is the Ancient Greek term for ibises. Why it was applied to the cattle egret is not clear.

Today, some authorities split the cattle egret into two species, the western (B. ibis) and the eastern (B. coromandus). Apart from minor differences, they are identical, so why this split was made, is a bit of a mystery to me.

Many other pictures, depicting this bird, are shown on the pages Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan, and Birds in the Himalaya.

When the British were ruling in India, hunters often shot the openbill for meat, calling it the ‘beef-steak bird’, a term that was also used for the woolly-necked stork (Ciconia episcopus).

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek anastomoo (‘to furnish with a mouth’), in this connection meaning ‘with mouth wide open’. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘yawning’, derived from oscitare (‘to yawn’), naturally also alluding to the beak.

The word stork originates in Ancient Germanic sturkoz.

The generic and specific names are the classical Latin term for stork.

Due to its intelligent behaviour, the raven appears in numerous mythologies. In Norse mythology, the ravens Hugin (‘thought’) and Munin (‘memory’) were the servants of the supreme god Odin, bringing news to him from all over the world. The raven figured on banners of Norse kings like Cnut the Great and Harald Hardrada. The raven was also an important bird to the Celts. According to Irish mythology, the goddess Morrígan alighted on the hero Cú Chulainn’s shoulder in the form of a raven after his death. In Welsh mythology, the name of the god Bran Fendigaid (in English called ‘Bran the Blessed’) means ‘raven’, and the bird was his symbol.

Among a number of peoples in Siberia, north-eastern Asia, and North America, the raven was regarded as a creator god. To the Tlingit and Haida peoples of Pacific North America, it was also a trickster.

Genesis 8: 6-7 says, “So it came to pass, at the end of forty days, that Noah opened the window of the ark, which he had made. Then he sent out a raven, which kept going to and fro, until the waters had dried up from the earth.”

The generic name is the classical Latin word for raven, whereas the specific name is a Latinized form of korax, the Ancient Greek term for raven. The English name derives from Old Norse hrafn, ultimately from Proto-Germanic khrabanas.

Even though the Indians for religious reasons leave the large birds alone, it declined drastically here for a number of years due to draining, increased cultivation, urban development, induatrial pollution, and increased usage of pesticides. In Indochina, it is threatened by draining, building of dams, overgrazing, poaching, and illegal collecting of eggs. The prolonged wars in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia also took its toll of cranes. In Australia, threats include draining and grazing by cattle.

Today, it is estimated that the total global population is 15-20,000, of which 8-10,000 are found in northern India, where it is now slowly recovering due to increased protection.

It is resident, but outside the breeding season it disperses to areas with abundant rainfall. The two eastern subspecies are found in wetlands, and outside the breeding season also in grasslands and farmland. The Indian subspecies is used to people and may nest in very small wetlands in agricultural areas.

In India, it is said that when the sarus cranes flock, it is a sign of the imminent monsoon rains. As cranes pair for life, the sarus crane is also a symbol of a happy marriage. In Hindu mythology, the goddess Baglamukhi has the head of a crane. She is a master of black magic and all sorts of killing with poisons.

In Greek mythology, Antigone was the daughter of Oedipus, who unwittingly killed his father Laius, king of Thebes, and married the widow, his mother Jocasta. When Jocasta learned the truth of their relationship, she hanged herself, and Oedipus, according to one version of the story, went into exile after blinding himself, accompanied by his daughters Antigone and Ismene.

The common name is the Hindi name of the bird.

The grey crowned crane lives in savannas and river valleys, and also sometimes in agricultural land, provided there are accessible wetlands. Traditionally, some tribes have regarded this bird as sacred, and in many places it has adapted to living near people. It is mainly sedentary, but moves around in search of areas with recent precipitation. It often spends the night in trees.

During the last 50 years or so, this species has declined drastically, and the total population may now be as low as 25-30,000, with two thirds of this number in East Africa. The decline is caused by draining, conversion of savanna to agricultural lands, and lack of flooding due to construction of dams. East African populations are classified as near-threatened, whereas the South African population is stable.

The generic name refers to the Balearic Islands in the Mediterranean. It is derived from grui Balearicae (‘the Balearic crane’), mentioned by Roman philosopher and naturalist Pliny the Elder (c. 23-79 A.D.). It is not known to which species Pliny referred, or even if it was a type of crane, although the demoiselle crane (Grus virgo) formerly occurred in Spain, and still migrates through the Nile Valley. (Source: J.A. Jobling 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names, Christopher Helm, London)

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘royal’, derived from regis (‘king’), of course alluding to the prominent crest.

The wattled crane is almost exclusively found in wetlands, being most numerous in the vast wetlands along rivers in Zambia and Botswana. It is resident, but moves about to areas with recent rainfall. Outside the breeding season, Ethiopian birds may be encountered in grasslands. This species usually lays only one egg and has a very slow reproduction rate. It doesn’t breed every year, only when ample rain has fallen. For this reason, dams have a huge negative effect on its reproduction.

The total population may be as low as 8.000-9.000 individuals, and almost everywhere it is steadily declining due to draining, dam construction, fires, and human settlement around wetlands. In South Africa, it has almost disappeared.

The generic name is onomatopoetic, referring to the loud trumpeting of cranes. The specific name is derived from the Latin caruncula (‘a small piece of flesh’, diminutive of carnis (‘flesh’), alluding to the red wattles under the bill.

This bird, which is restricted to wetlands, was formerly widely distributed in northern Siberia, but has been declining drastically since the 1800s. The eastern population, counting 3500-3800 individuals, predominantly breeds in the Yakutia Republic and a little further eastwards. It is wintering at the Yangtze River in China, 98% in Lake Poyang. A part of this lake is protected, but is threatened by a collection of huge dams, Three Gorges, which now control the annual inundations of the lake area. Other threats include mercury poisoning and oil drilling in Siberia.

The central and western Siberian populations, whionce bred along the Ob River, are now practically extinct. The western population spent the winter around the Caspian Sea. In the 1990s, up to 10 birds could still be seen there, but the number dwindled to 4 in 2002, and just a single bird since 2010.

The central population spent the winter in northern India. In Keoladeo National Park, up to around 200 birds were still found here until the 1960s, but the number was declining alarmingly, and in the 1970s only about 75 birds remained.

The International Crane Foundation attempted to try to save this population by placing eggs of Siberian cranes in nests of common cranes, which would then rear the young. But numbers still declined in Keoladeo to count just 4 individuals in 1996, and the last observation was in 2002. The birds were shot for human consumption during the migration through Afghanistan and Pakistan. In Keoladeo, attempts have been made to hatch eggs of Siberian cranes in nests of sarus cranes, but the young were imprinted on their foster parents and stayed with them year-round in the area.

In Ancient times, the Siberian crane was wintering as far west as Egypt. A relief from Saqqara, which is now in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen, depicts 6 Siberian cranes, and there is also a picture depicting a Siberian crane in Senet’s grave from the 12th dynasty (1991-1785 B.C.). A Siberian crane is also mentioned in a text, written by Egyptian author an-Nuwayri (1279-1332 A.D.).

The generic and specific names are derived from Ancient Greek leukos (‘white’) and geranos (‘crane’).

Four subspecies are migratory, spending the winter as far south as South Africa, northern Australia, and Argentina. The birds may be seen year-round in southern Mexico, southern Iberian Peninsula, Egypt, the Himalaya, southern China, and Taiwan.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘rural’, derived from ruris (‘countryside’). In his Historiæ animalium, Liber III, published in 1555, Swiss physician and naturalist Konrad Gessner (1516-1565) calls the bird Hirundo domestica, from the Latin domus (‘house’). The barn swallow mostly builds its nest on or inside buildings, very often in stables or barns – hence its common name.

It may be told from the barn swallow (above) by its shorter outer tail feathers, the greyish, checkered vent, and lack of black breast band.

The generic name is the classical Latin term for swallows.

Previously, birds in southern India and Sri Lanka were included in this species, but are now regarded as a separate species, called hill swallow (H. domicola).

The generic name is Ancient Greek, meaning ‘stupid’ or ‘foolish’. In the old days, sailors often killed these birds for food, and they found them very stupid, as they were confiding and thus easy to kill. The specific name is Latin, also meaning ‘stupid’ or ‘foolish’.

In former days, this species was very common in most of Europe, but has declined drastically during the last 30 to 40 years.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek khroizo (‘to colour’) and kephale (‘head’), alluding to the dark head of many of the species in the breeding season. The specific name is from the Latin ridere (‘to laugh’), referring to one of its calls, ke-ke-ke, mostly heard in the breeding colonies. Despite its common name, the head (in the breeding plumage) is not black, but a dark chocolate brown.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek gelao (‘to laugh’) and khelidon (‘swallow’), alluding to its call and its elegant flight style. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘of the Nile’, presumably the type locality. The common name alludes to the rather heavy bill of this bird.

Previously, the Australian gull-billed tern (G. macrotarsa) was considered a subspecies of the common gull-billed tern, but is today regarded as a separate species.

In later years, numbers of European herring gulls have increased significantly in cities, where the birds place their nest on top of high-rise buildings.

The generic name is a Latinized form of Ancient Greek laros, pertaining to a kind of ravenous sea bird, presumably a gull. The specific name is derived from the Latin argentum (‘silver’) and the suffix atus (‘resembling’), thus ‘silvery’, presumably alluding to its pale grey wings.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘marine’, derived from mare (‘sea’).

The specific name is a misspelling of the name of German physician and zoologist Georg Christian Karl Wilhelm Michahelles (1807-1834) who collected birds in Dalmatia and Greece. He died of dysentery in Greece, only 27 years old.

The generic name is derived from the Icelandic name of the bird, rita, whereas the English name was given in allusion to its call. The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek tridaktylos (‘three-toed’), referring to the fact that this species is missing the small, back-pointing fourth toe, which most other gull species possess.

In North America, this species is called black-legged kittiwake to differentiate it from its near relative, the red-legged kittiwake (R. brevirostris), which breeds on small islands in the far northern Pacific.

It also breeds in a few tropical areas, e.g. in the Bahamas and Cuba, and on small islands off Venezuela. Since 1980, small breeding colonies have existed on islands off the east and west coasts of Sri Lanka.

It spends the winter along coasts from about 20 degrees northern latitude southwards to southern South America, Africa, and Australia.

The generic name is derived from Old English stearn, which appears in the poem The Seafarer, from the 10th Century. A similar word was used for these birds by the Frisians, whereas the Scandinavians used, and still use, the word terne (Danish and Norwegian) or tärna (Swedish).

The specific name is the Latin name of swallows. It dates back to the 1600s, where the bird was called Hirundo marina (‘sea-swallow’) by English ornithologist and ichthyologist Francis Willughby (1635-1672). The name alludes to the elegant flight of terns.

It is famous for its long-distance migration, flying from the northern breeding areas to Antarctica and back again every year, the shortest distance between these areas being 19,000 km. This means that it experiences two summers per year. One speculates if the bird doesn’t like dark nights.

A Dutch tracking study from 2013 has concluded that the average annual migration is about 48,700 km. An Arctic tern may live up to 30 years, and during its lifetime it may travel up to 2.4 million km.

Some examples of its long-distance migration: An adult bird, which was ringed on the island of Saltholm, Denmark, in May 1958, was shot along the pack ice close to the Antarctic coast south of Australia, in February 1959 – a distance of about 15,700 km. A chick, which was ringed in summer 1982 on the Farne Islands, Northumberland, England, reached Melbourne, Australia, in October, just 3 months after fledging – a journey of more than 22,000 km. A third example is a chick ringed in Labrador, Canada, in July 1928, which was found in South Africa 4 months later – a distance of about 12,600 km.

The specific name probably refers to the beauty and elegance of this bird.

During the 20th Century, most European populations declined drastically due to habitat loss, pollution, and human disturbance.

The generic name is a diminutive of Sterna (see above), in which genus they were formerly included. The specific name is derived from the Latin albus (‘white’) and frons (‘forehead’).

The nominate race alba is found in eastern Greenland, Iceland, and the entire Europe, apart from the British Isles, and further east, almost to the Ural Mountains. In the British Isles, it is replaced by the race yarrellii, in Morocco by subpersonata, and from the Ural Mountains southwards to the Caspian Sea by dukhunensis. In Siberia and western Alaska, the race ocularis is breeding, in Iran persica, in the western part of Central Asia personata, in Central Asia baicalensis, in the Himalaya alboides, in China, Korea and Taiwan leucopsis, and in Japan, Sakhalin and Kamchatka lugens. Many of the northern races are migratory, whereas the southernmost are resident.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for this bird. It is derived from motare (‘to move’ or ‘to shake’), and the diminutive suffix illa, thus ‘the little shaker’, alluding to the tail of the white wagtail always bobbing up and down. However, some time during the Middle Ages the erroneous belief arose that cilla meant ‘tail’. (Source: J.A. Jobling 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm, London)

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘white’.

It lives in open forest, secondary growth, and gardens, found in the major part of the Indian Subcontinent, from Indochina eastwards to central and eastern China, and thence southwards to Indonesia. It is the national bird of Bangladesh.

A number of pictures, depicting this species, are shown on the pages Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan, and Birds in the Himalaya.

In his 3-volume work A natural history of birds : illustrated with a hundred and one copper plates, curiously engraven from the life (1731-1738), English naturalist and illustrator Eleazar Albin (c. 1690-1742) calls this bird Dial Bird or Bengall Magpie. The former name alludes to the Hindi name of the bird, dayal. Some authorities have suggested that when Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) included it in his Systema Naturæ in 1758, he named it Gracula saularis, misunderstanding Albin’s name, thinking it had something to do with a sun dial. He then meant to call it Gracula solaris (solaris, ‘of the sun’), but by mistake wrote saularis instead.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kopsykhos, the name of the blackbird (Turdus merula), but also generally meaning ‘thrush’.

It is distributed from Tajikistan and Afghanistan along the Himalaya to Bangladesh, Indochina, most of China, and Taiwan, living exclusively along fast-flowing streams and often seen perched on a rock, from where it takes off to snap some bypassing insect.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek phoinix (‘crimson’) and oura (‘tail’), like the English name referring to the red tail of these birds. Start is an old word for tail. The specific name is from the Latin fuligo (‘soot’) and ous (‘prone to’), alluding to the slaty-black colour of the male.

The generic name is derived from pelekan, the Ancient Greek name of pelicans. The specific name refers to the Philippines, where the species was first collected. It was abundant here until the early 1900s, but became extinct as a breeding bird in the 1960s.

The generic name is derived from the Greek phalakros (‘bald’) and korax (‘raven’), where ‘bald’ refers to the white (but feathered) crown of the great cormorant (below) during the breeding season, whereas ‘raven’ presumably alludes to its otherwise black plumage.

In the 1800s, this species was persecuted all over Europe, partly because it was competing with fishermen, partly because its guano destroyed the trees, in which it was breeding. The complete contrast to this persecution is seen in the Far East, where fishermen, for thousands of years, have been using tamed great cormorants for fishing. Pictures, depicting this practice, are found on the page Fishing.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘charcoal’, alluding to its predominantly black plumage.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek alektoris (‘chicken’). The specific and popular names refer to the bird’s call, a far-reaching chuck-chuck-chukar-chukar.

The generic (and specific) name is the classical Latin word for rooster.

The domestic chicken is described in depth on the page Animals – Animals as servants of Man: Poultry.

It is the national bird of Nepal, locally called danphe, and often referred to as ’the bird of nine colours’. In sunshine, the brilliant plumage of the male is glittering in almost all imaginable colours. The female is brownish and heavily streaked, with naked blue skin around the eyes and a pale patch on the throat.

It is also the state bird of Uttarakhand.

As with most other gamebirds, the meat of monal is delicious, and for this reason it is hunted in many places. However, it is still common locally, and in the Khumbu area of eastern Nepal it is very common, as the local Buddhist Sherpas are against killing. So even though the monal does some damage by digging up potatoes and eating them, they are not persecuted here.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek lophos (‘crest’) and phoros (‘bearing’), alluding to the small crest of this species.

The specific name commemorates Lady Mary Impey, wife of Sir Elijah Impey (1732-1809), who was chief justice of the Supreme Court at Fort William, the first settlement of the British East India Company in Bengal.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for peafowl. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘crested’.

The classical Greek word for peacock was taos, derived from Persian tavus. The famous Peacock Throne, in Persian known as Takht-i-Tavus, was a splendid piece of Mughal workmanship, covered in gold and jewels. It was commissioned in the early 17th Century by Emperor Shah Jahan (1592-1666), and located in the Diwan-i-Khas (Audience Hall) in the Red Fort in Delhi. It got its name from two dancing peacocks, depicted at its rear.

By the beginning of the 18th Century, the power of the Mughal Empire was crumbling, and in 1739 Nader Shah (1688-1747), a Turkoman Muslim from north-eastern Iran, invaded Delhi with his army, killing tens of thousands of its inhabitants. When they left in 1739, they brought with them the Peacock Throne and many other valuables as war trophies. When Nader Shah was assassinated by his own officers in 1747, the throne disappeared, most probably being destroyed for its valuables.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for coot. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘ornamented with a bracelet’, like the common name alluding to the red ‘garters’ on its legs, contrasting with the yellowish-green feet.

The specific name means ‘crested’, a somewhat erroneous name for the red knobs on the forehead.

The generic name is Latin for ‘little hen’, whereas the specific name is derived from Ancient Greek khloros (‘green’) and pous (‘foot’).

In the Americas, this species is replaced by the similar common gallinule (G. galeata), which was formerly regarded as a subspecies of the moorhen. It is described on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in the United States and Canada.

The generic name is a diminutive of the Greek sphenos (‘wedge’), in reference to the thin, wedge-shaped flippers of these birds. The specific name means ‘plunging’ in the Latin.

Other pictures, depicting this species, are shown on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in Africa.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of the Eurasian eagle-owl (Bubo bubo). The specific name refers to the state of Virginia. Presumably, the type specimen was collected there.

It has yellow feet, reflected in the specific name, derived from the Latin flavus (‘yellow’) and pes (‘foot’).

The generic name is derived from the Malay word for fish-owl, ketupok.

Some authorities include these birds in the genus Bubo.

Previously, birds in north-western Africa and the Himalaya were regarded as subspecies of the tawny owl, but have since been upgraded to separate species, called the Maghreb owl (S. mauritanica) and the Himalayan owl (S. nivicolum).

The generic name is the Ancient Greek word for owl. The specific name stems from the Italian name of the tawny owl, allocco, ultimately from the Latin ulucus, which refers to some type of screeching owl.

The northern ostrich, ssp. camelus, was once widespread in northern Africa, but has disappeared from large parts of its former range. It is today considered critically endangered.

The Somali ostrich, ssp. molybdophanes, which has a bluish neck and legs, lives in southern Ethiopia, north-eastern Kenya, and Somalia. Some authorities regard it as a separate species, S. molybdophanes. This seems rather odd to me, as other ostriches, which are regarded as a single species, live both north and south of this population.

The male Masai ostrich, ssp. massaicus, has pink neck and legs, the female greyish. It is found from southern Ethiopia and southern Somalia southwards to southern Tanzania.

The southern ostrich, ssp. australis, has grey neck and legs. It is widely distributed south of the rivers Zambezi and Cunene. In some places, it is farmed for meat, leather, and feathers.

The Arabian ostrich, ssp. syriacus, which was formerly very common in the Arabian Peninsula, Syria, and Iraq, became extinct around 1966 due to overhunting. Wealthy Arabs, armed with the most modern weapons, pursued anything larger than foxes from jeeps, such as oryx, gazelle, and ostrich, and everything was gunned down mercilessly.

Attempts to reintroduce the species to Israel have failed. In Australia, escaped ostriches have established feral populations.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of the bird. The specific name refers to its great size and its way of walking.

Other pictures, depicting this species, are shown on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in Africa.

The generic name is the Icelandic and Faroese name of the northern gannet (Morus bassanus). The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek dactyl (‘finger’) and from the Latin ater (‘black), alluding to the black, splayed wingtips in flight.

The name booby is derived from Old Spanish bobo (‘stupid person’), given by seamen who often collected seabirds for food. Due to the lack of fear shown by these birds at the breeding ground, they were easy to kill, and therefore labelled ‘stupid’.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek threskeia (‘religious worship’) and ornis (‘bird’), alluding to the sanctity of the sacred ibis (T. aethiopicus) in Ancient Egypt. The specific name is a Latinized version of Ancient Greek melas (‘black’) and kephale (‘head’).

This species is migratory, spending the winter in western Europe, and around the Mediterranean, the Black Sea, and the Caspian Sea. Some birds in south-western Norway and Scotland are resident.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for thrush. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘of the flanks’, derived from ile (‘flanks’), naturally alluding to the red flanks.