Grasses

Withered grass tufts, Atacama Desert, Chile. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Late afternoon light illuminates a grass-clad plain around a lake, Corbett National Park, Uttarakhand, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Withered grass tufts and Mojave yuccas (Yucca schidigera) in the Colorado Desert, Joshua Tree National Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Boys, playing with a wheelbarrow in a sea of silver-headed grass, Tumlingtar, Arun Valley, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Savanna in morning light, with grazing impalas (Aepyceros melampus), Tarangire National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grass at sunset, growing on the shore of the Ayeyarwady River, Bagan, Myanmar. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grass-clad hills in morning light, Hutiao Xia (‘Tiger Leaping Gorge’), Jinsha River, Yunnan Province, China. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red grass in morning light, Crystal Cove State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grazing Gotland sheep in late autumn afternoon light, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sinhalese girl, picking grass, Dambulla, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

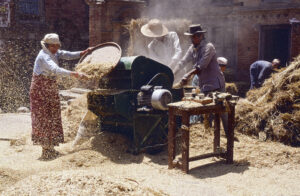

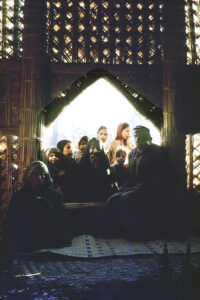

Women, planting rice plants in a flooded field, central Myanmar. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The bottom picture above reminds me of a true story from Taiwan.

A teacher brought his young students, who had grown up in the heart of a city, out to a rice field so that they could learn where the food came from. One of the kids was afraid to step into the field, as he thought he would sink into it.

The teacher heard one of the other kids saying: “Oh no, you don’t have to be afraid! There is cement underneath!”

The old hometown looks the same,

As I step down from the train,

And there to meet me is my mama and papa.

Down the road I look, and there runs Mary,

Hair of gold and lips like cherries.

It’s good to touch the green, green grass of home.

Yes, they’ll all come to meet me,

Arms reaching, smiling sweetly.

It’s good to touch the green, green grass of home.

The old house is still standing,

Though the paint is cracked and dry,

And there’s that old oak tree that I used to play on.

Down the lane, I walk with my sweet Mary,

Hair of gold and lips like cherries.

It’s good to touch the green, green grass of home.

Then I awake and look around me,

At four grey walls that surround me,

And I realize, yes, I was only dreaming,

For there’s a guard, and there’s a sad, old padre.

On and on, we’ll walk at daybreak,

Again, I’ll touch the green, green grass of home.

Yes, they’ll all come to see me

In the shade of that old oak tree,

As they lay me ‘neath the green, green grass of home.

Green, Green Grass of Home, country song, written by American songwriter Claude Putman Jr. (1930-2016).

Grasses are a huge, very successful plant family, Poaceae, also known as Gramineae, comprising about 780 genera and 12,000 species. It is found in almost any habitat on the globe, and on all continents, including Antarctica, where a single species is found in the western peninsula. The family names are derived from poa, the Ancient Greek term for fodder, and from gramen, the classical Latin term for grasses.

These plants are characterized by having hollow stems, except at the nodes, popularly called knees. Each leaf grows from a node, the lower part enclosing the stem and forming a sheath. At the base of the leaf, there may be a membrane, or a ring of hairs, the ligule. The stem is usually circular, sometimes flattened, but never triangular like the sedges (Carex).

The inflorescence may be a spike, consisting of a long row of stalkless spikelets, each with one or several flowers, or a panicle, an often pendent, many-branched inflorescence with stalked spikelets. The stamens are characteristic, the anthers hanging from the end of a very thin, thread-like filament, often pulling it downwards.

The bract that surrounds the seed is called chaff, and in many species a more or less stiff hair, the awn, grows out from the base of the chaff.

On this page, nomenclature largely follows Kew Gardens’ website Plants of the World Online (powo.science.kew.org). Regarding the etymology, I have relied on the website Wiktionary, and on an excellent book by Jens Corneliuson: Växternas namn. Vetenskapliga växtnamns etymologi. Språkligt ursprung och kulturell bakgrund (‘Etymology of scientific plant names’), Wahlström & Widstrand, 1999 (in Swedish).

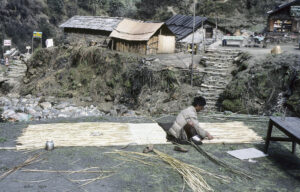

Grasses have hollow stems, clearly demonstrated in this picture, in which a Sasak tribal woman is carrying bamboo stems to her village near Senaru, Mount Rinjani, Lombok, Indonesia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grass leaves grow from nodes, the lower part enclosing the stem and forming a sheath, often quite long. These pictures show greater sweet-grass (Glyceria maxima), Ejstrup Lake, central Jutland, Denmark, and reed canary-grass (Phalaris arundinacea), covered in rime, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The inflorescence of grasses may be a spike as in crested dog’s-tail (Cynosurus cristatus) (top), or a panicle as in barren brome (Bromus sterilis), both photographed on the island of Bornholm, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grass anthers are often colourful, hanging at the end of a very thin, thread-like filament. These pictures show flowering cock’s foot (Dactylis glomerata), Bornholm, Denmark (top), couch grass (Elymus repens), Roskilde Fjord, Denmark, and an unidentified species in Hanoi, Vietnam. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chaff and awn of wild oat (Avena fatua), naturalized in Crystal Cove State Park, California. It is very similar to the cultivated oat (A. sativa), but may immediately be identified by the very long awn. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bamboo

Bamboo is a term applied to various types of grasses, mostly found in warmer regions of the world. This group, comprising about 1,400 species in 115 genera, is divided into three tribes, tropical woody bamboos (Bambuseae), temperate woody bamboos (Arundinarieae), and herbaceous bamboos (Olyreae). They vary enormously in size, from less than 1 m to over 30 m tall.

Most bamboo species rarely blossom, some only flowering at intervals of 65 to 120 years. Mass-flowering is common in many species, and once flowering has taken place, the plants spread the seeds, wither, and die.

Bamboo is of huge value to many cultures, utilized for production of a large number of items (see caption Grasses and Man).

Bamboo forest surrounds a lake in Parambikulam Wildlife Sanctuary, Kerala, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

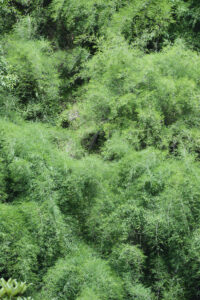

Stands of bamboo in a subtropical evergreen forest, Huoyan Mountain (’99 Peaks’), Pinglin, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dwarf bamboo forest, Lower Langtang Valley (top), and Lower Marsyangdi Valley, Annapurna, both in Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dwarf bamboo, Modi Khola Valley, Annapurna, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stem of a dwarf bamboo, bent down by newly fallen snow, between Tharepati and Melamchigaon, Langtang National Park, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Foggy morning at Sauraha, in the Nepal Terai, the tropical lowland plains beneath the foothills of the Himalaya. On his way to work in the fields, a farmer is hurrying past a growth of bamboo. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young bamboo shoot, Sun-Moon Lake, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On bamboo stems, the sheaths often remain for a long time, even though they have withered. – Yin Tan waterfall, Rueilli (top), and ’99 Peaks’, near Fangyuan, both in Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flowering bamboo, Dandeli Wildlife Sanctuary (upper 2), and Anshi National Park, both in Karnataka, India. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These bamboo plants, which have just flowered, are now dying, stretching their withering stems towards the sky, Dandeli Wildlife Sanctuary. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Black-footed langur (Semnopithecus hypoleucos), climbing up a dying bamboo stem, Anshi National Park, Karnataka, India. This species and many other monkeys are described on the page Animals – Mammals: Monkeys and apes. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bamboo with seeds, Dandeli Wildlife Sanctuary, Karnataka, India. The bird is a spotted dove (Spilopelia chinensis). This species is described on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Seed-bearing dwarf bamboo, Ubud, Bali, Indonesia. In the lower picture, Javan munias (Lonchura leucogastroides) are feeeding on the seeds. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Vernal hanging parrot (Loriculus vernalis), eating bamboo seeds, Anshi National Park, Karnataka, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Selected grass species

Arranged in alphabetical order, according to generic and specific names.

Agrostis Bentgrass

This large genus, comprising about 190 species, is widely distributed on all continents, except Antarctica, and it is also absent from certain rainforest and desert areas.

The generic name is Ancient Greek, originally a term translated as ‘a grass that mules feed on’, possibly couch grass (Elymus repens).

Agrostis gigantea Black bentgrass

This plant is native to temperate regions, from western Europe (except Iceland and the British Isles) eastwards to the Pacific Ocean, and from Scandinavia and Siberia southwards to North Africa, Iran, and northern Indochina. It has become widely naturalized elsewhere, especially in North America, where it was widely cultivated as a pasture grass until the 1940s.

It grows in a variety of habitats, including open woodland, grasslands, roadsides, and waste ground, and as a weed in agricultural areas.

Black bentgrass, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Agrostis stolonifera Creeping bentgrass

This species is quite similar to black bentgrass, but may immediately be identified by its numerous runners. It has the same distribution, but is also native to Iceland and the British Isles. It mainly grows in meadows and along rivers, but may also be found in open forests and disturbed sites. In meadows, it often forms dense, carpet-like growths.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘bearing stolons’ (runners).

Large growth of creeping bentgrass in a littoral meadow, Møn, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Alopecurus Foxtail

This genus, counting about 43 species, is widely distributed in subarctic, temperate, and subtropical areas of the Northern Hemisphere, and also in cooler regions of western South America.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek alopex (‘fox’) and oura (‘tail’), genitive urus, alluding to the shape of the spike.

Alopecurus aequalis Orange foxtail

This species is very widely distributed, found in temperate and subarctic areas of the Northern Hemisphere, southwards to southern United States, North Africa, the Himalaya, and China, and also in the northernmost part of the Andes. It may be identified by the yellowish-green spike and the inflated leaf sheaths.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘equal’ – equal to what is not clear.

Orange foxtail, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Alopecurus arundinaceus Creeping foxtail

This plant resembles the previous species, but may at once be identified by its dark inflorescences. Stem erect, to 1.1 m tall, mostly solitary from the ends of long rhizomes. Leaf to 40 cm long and 1.2 cm wide, upper sheaths somewhat inflated, spike to 10 cm long, dark.

It is partial to humid grasslands, including saline ones, in mountains found up to an elevation of about 1,200 m. It is native to the major part of Europe, eastwards to the Pacific Ocean, southwards to northern Africa, Iran, western Himalaya, and northern China. It has been widely introduced elsewhere as a fodder plant and for erosion control.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek arundo, the classical name of giant reed (Arundo donax, below), but it may also mean ‘reed’ in general, in this case probably alluding to the reed-like leaves.

Creeping foxtail, Gräsgårds Hamn, Öland, Sweden. In the background fishermen’s sheds. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Alopecurus geniculatus Marsh foxtail

Native to all of Europe, eastwards to the Ural Mountains, and thence southwards to North Africa, Turkey, the Caucasus, Kazakhstan, and north-western Himalaya. It has also become naturalized elsewhere, including Australia and North America. It is partial to moist meadows.

This plant, which grows to about 60 cm tall, resembles orange foxtail, but has green spikes, and the sheaths are not inflated. The stem is often bent at the nodes. It is able to reproduce vegetatively by rooting at the nodes.

The specific name is derived from the Latin genu (‘knee’) and culum, a diminutive suffix, thus ‘little knee’, alluding to the bent nodes.

Marsh foxtail, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Alopecurus pratensis Meadow foxtail

As its name implies, this species is partial to meadows, but avoids wetter ones. It is found all over Europe, and thence eastwards to eastern Siberia, southwards to the Mediterranean, Iran, and northern China. It is also widely cultivated for fodder and has become naturalized elsewhere, including Australia and North America.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘of meadows’.

Meadow foxtail, Sassolungo, Dolomites, Italy (top), and Bornholm, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ammophila arenaria, see Calamagrostis arenaria.

Anthoxanthum

This genus with about 50 species is widespread in the Northern Hemisphere, with a patchy occurrence in South America, southern Africa, Southeast Asia, and Australia.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek anthos (‘flower’) and xanthos (‘yellow’), alluding to the spikes of A. odoratum (below) turning yellow when ageing.

Anthoxanthum nitens Sweetgrass

This fragrant grass, by many authorities called Hierochloe odorata, is very widespread in subarctic and temperate areas of the Northern Hemisphere, southwards to the United States, Iran, and China. It is found in humid grasslands, mainly along rivers and lake sides.

The stem is to about 50 cm tall, the leaves often growing outwards horizontally, to a length of 1 m or more.

The specific name is from the Latin niteo (‘shining’ or ‘thriving’), probably alluding to the lush growth of the leaves.

The alternative generic name is derived from Ancient Greek hieros (‘sacred’) and chloe (‘young green shoot’). Because of its fragrance, it was strewn at church doors on saints’ days in northern Europe. It has also been used in France to add flavour to candy, tobacco, soft drinks, and perfumes, and in Poland it has been added to vodka.

Sweetgrass, covering the ground in a reedbed, Ringkøbing Fjord, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flowering sweetgrass, Ringkøbing Fjord. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anthoxanthum odoratum Sweet vernal grass

This species is native from Iceland eastwards to western Siberia, southwards to North Africa, Turkey, and Mongolia.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘fragrant’.

Sweet vernal grass, growing among coastal rocks together with sheep’s-bit (Jasione montana), Gudhjem, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sweet vernal grass in evening light, Fanø, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Apera

This small genus with 5 species is found from Europe eastwards to eastern Siberia, southwards to Mauritania, Egypt, Pakistan, and southern Siberia.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek a (‘not’) and peros (‘mutilated’), i.e. ‘unadulterated’. What it refers to is not clear.

Apera spica-venti Common windgrass

Common windgrass is native to from Denmark eastwards to Yakutia, southwards to Mauritania, Egypt, Iran, and Kazakhstan, and has become naturalized in northern Europe and North America.

It is a common weed in fields with winter cereals.

The specific name is Latin-Italian, meaning ‘twenty spikes’, alluding to the numerous spikes.

Common windgrass, growing at a roadside together with cornflower (Centaurea cyanus), Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Common windgrass, Mols, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Arrhenatherum

A small genus with 7 species, distributed from the entire Europe, including Iceland, eastwards to the Ural Mountains and Kazakhstan, southwards to northern Africa, Jordan, and Iran.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek arrhenos (‘male’) and atheros (‘bristle’), alluding to the fact that only the male flowers have awns.

Arrhenatherum elatius False oat-grass

This grass, growing to 1.5 m tall, is very common, found from Iceland eastwards to the Ural Mountains, southwards to North Africa, Iran, and Kyrgyzstan.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘tall’.

False oat-grass, southern Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

False oat-grass with raindrops, Rossfeld, near Berchtesgaden, southern Germany. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flowering false oat-grass, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Arundo

This small genus, comprising 5 species, occurs from the Mediterranean eastwards to Kazakhstan and Japan, southwards to Yemen, India, Indochina, and the Philippines.

The generic name is the classical Latin term for several reed species with stiff, bamboo-like stems.

Arundo donax Giant reed

This huge grass is often to 6 m tall, sometimes even to 10 m. It is native from Turkey, Jordan, Arabia, and Kazakhstan eastwards across central and southern Asia to Japan, but has become widely naturalized elsewhere.

In western United States it has been extensively planted as a means to control soil erosion, and as a biomass plant, but it often escapes and has become highly invasive in numerous places, especially along rivers, where it often displaces the natural vegetation.

The specific name is the Ancient Greek name of this species.

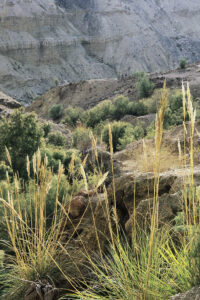

Giant reed in one of its native areas: Wadi Zarqa Main, Jordan Valley, Jordan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this picture, giant reed grows on a bluff in Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park, Big Sur, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Arundo formosana Formosan giant reed

This species usually grows in dry coastal grasslands and on sea cliffs, but is sometimes found inland, often forming dense masses of leaves, and with large, pendent inflorescences. It occurs from Iriomote Island in the south Ryukyu Islands, Japan, southwards through Taiwan to the Philippines.

The stems are slender, often pendent, to 1.2 m tall/long and to 6 mm across, branching from the nodes. Leaf sheaths are longer than the internodes, smooth, blade to 25 cm long and 1.5 cm broad, basal part with long silky hairs. Inflorescence is a panicle, to 30 cm long, pale brown, spikelets to 1 cm long, with 2-5 florets.

The stems are used for making baskets.

Formosa is the old Portuguese name of Taiwan, meaning ‘beautiful’.

Formosan giant reed, Tungling Forest, near Wufong, western Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Avena Oat

This genus contains about 27 species, distributed from the entire Europe eastwards to eastern Siberia, southwards to northern and eastern Africa, Arabia, Sri Lanka, and southern China.

The generic name is the classical Latin term for oat.

Avena barbata

Stem to 1.2 m tall, ascending or erect, solitary or in groups. Leaf sheaths densely hairy, ligule blunt, to 6 mm long, leaf blade linear, pointed, to 25 cm long and 2 cm wide, hairy or smooth. The inflorescences are spreading panicles, to 35 cm long and 15 cm wide, at the end of stalks, to 18 cm long, spikelets to 2.5 cm long, with 2-3 florets, chaff lanceolate, to 2.5 cm long, with 5 or 7 veins, awn to 3 cm long, densely hairy at its attachment.

The specific name may refer to the long awns, or to the tuft of hairs at their base.

Avena barbata, Esemçe, near Mudanya, Marmara Sea, Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Avena fatua Wild oat

Stem to 80 cm tall, ascending or erect, smooth. Leaf sheaths hairy or smooth, ligule blunt, to 6 mm long, leaf blade linear, pointed, to 25 cm long and 1 cm wide, smooth or scaly. The inflorescences are spreading panicles, to 40 cm long and 12 cm wide, spikelets to 2.7 cm long, with 2-3 florets, chaff lanceolate, pointed, to 2.7 cm long, 7-9-veined, awn to 3.5 cm long, often bent or twisted.

This plant grows in open areas and is a common weed in fields and plantations, found from sea level up to altitudes around 1,500 m.

It is believed to have originated in Central Asia and has been associated with the cultivation of the common oat (A. sativa) and other cereals since the early Iron Age. Wild oat also has edible seeds, but is unsuitable for cultivation due to the fact that as soon as the kernels are ripe they fall to the ground, as opposed to the cultivated oat.

In former days, wild oat was so numerous that in certain areas it would lower the yield of crops by 40%. In Denmark, it was declared an outlaw in 1956, to be “removed from all cultivated and un-cultivated areas by the owner or the user.”

Before the introduction of chemical herbicides, the plants had to be removed by hand, which was a very time-consuming task. However, it was an advantage that wild oat is often taller than the surrounding crop, making it relatively easy to spot.

Today, wild oat is still is a serious pest in many countries, and as it is highly adaptable to various environments, it has become naturalized in numerous places. It is regarded as being among the world’s worst agricultural weeds. (Sources: D.P. Jones (ed.) 1976. Wild oats in world agriculture. An interpretative review of world literature. Agricultural Research Council. London; and L.G. Holm et al. 1977. The World’s Worst Weeds. Distribution and Biology. University Press of Hawaii)

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘tasteless’ – an odd name, as the seeds are edible. The name is probably derogatory, alluding to the seeds falling off soon after ripening, thus being worthless.

Wild oat, Djursland, Denmark (top), and near Rokka, north-western Crete. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Avenella

This genus contains only 2 species, the widespread A. flexuosa (below), and A. foliosa, which is restricted to the Azores.

The generic name is derived from the Latin Avena (‘oat’) and ella, a diminutive suffix, thus ‘small oat’.

Avenella flexuosa Common hair-grass

This plant, previously known as Deschampsia flexuosa, forms tussocks, with delicate stems to 30 cm tall, and panicles with thin, wavy stalks. It grows in dry grasslands, on moors and heaths, and in birch woodlands, always on acidic soils.

It is very widespread in the Northern Hemisphere, and is also found in montane areas of southern South America, central parts of Africa, and Indonesia.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘winding’, alluding to the panicle stalks.

Large growth of common hair-grass, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Common hair-grass, growing in a crack in a rock, Aspeberget, Bohuslän, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Common hair-grass with raindrops, Thy, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Close-up of common hair-grass, seen against the light, Fanø, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bambusa

A large genus with about 150 species, occurring from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to Taiwan and the Philippines, and thence southwards to northern Australia.

The generic name is derived from Dravidian banbu or Malayan bambu, both local words for bamboo.

Bambusa ventricosa

This bamboo, growing to 10 m tall, is native to south-eastern China and Vietnam, but is widely cultivated in subtropical regions around the world as an ornamental.

In stressing conditions, this plant develops short, swollen internodes, hence the popular name Buddha’s Belly – not alluding to the Buddha Sakyamuni, but to the fat-bellied Budai, often called ‘The Laughing Buddha’, who is a bodhisattva. More about this issue is found on the page Religion: Buddhism, and pictures depicting The Laughing Buddha are shown on the page Culture: Wood carvings.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘distended’.

This specimen of Bambusa ventricosa, growing in the Botanical Garden, Dehra Dun, Uttarakhand, India, is thriving, so the internodes are only moderately swollen. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bambusa vulgaris Common bamboo

A large bamboo, stems growing to 20 m tall and 10 cm thick, and often forming large clumps. It originated in Indochina and the Yunnan Province of China, but is widely cultivated elsewhere as an ornamental plant and has become naturalized in many countries.

Many varieties have been created through selection, including var. striata, which has a bright yellow stem with longtudinal green streaks.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘common’.

Evening sunshine illuminates stems of the green-striped variety of common bamboo, Mysore, Karnataka, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Close-up of the green-striped variety, Botanical Garden, Dehra Dun, Uttarakhand, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bonnet macaque (Macaca radiata), resting among stems of the green-striped variety, Periyar National Park, Kerala, India. This species and many other monkeys are described on the page Animals – Mammals: Monkeys and apes. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tiny spiders have spun their webs between stems of the green-striped variety, Basianshan National Forest, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Brachypodium

A genus with around 20 species, found from Europe eastwards to eastern Siberia and Japan, southwards to southern Africa, Madagascar, Indonesia, and New Guinea.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek brachys (‘short’) and pous (‘foot’), alluding to the very short-stalked spikelets of these plants.

Brachypodium sylvaticum Wood false brome

This tufted grass, growing to 90 cm tall, is found in a huge area, stretching from Europe eastwards to central Siberia, Sakhalin, and Japan, southwards to North Africa, Ethiopia, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and New Guinea. It has been introduced to North America, where it has become an invasive plant in many areas, often outcompeting native species.

It is partial to shady forests, often growing along trails and forming large populations. It has narrow, drooping, to 15 cm long spikes, with very short-stalked spikelets.

The specific name means ‘growing in forests’, derived from the Latin silva (‘forest’).

Wood false brome, Funen (upper 2), and northern Zealand, both in Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Briza Quaking-grass

This genus with 5 species occurs from Europe eastwards to central Siberia, southwards to northern Africa, Iran, the Himalaya, and southern China, but is absent from large regions of Central Asia.

In Ancient Greece, briza was the name of an unknown grass with an intoxicating effect, perhaps a species of Lolium (below), derived from brizo (‘being sleepy’ or ‘nodding from fatigue’). The toxins were not in the grass itself, but in galls or other parasites on the plant.

The English name refers to the dried spikelets, which quiver in even slight breezes. Other popular names include rattle grass and rattlesnake grass.

Briza maxima Large quaking-grass

This plant is native to all countries in and around the Mediterranean, but is often cultivated elsewhere and has become naturalized in numerous countries around the globe.

It may grow to a height of 60 cm. Seeds and leaves are edible.

Large quaking-grass, near Kentroxori, Crete (top), and near Casares, Andalusia, Spain. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Briza media Common quaking-grass

This elegant grass resembles the previous species, but is more slender, with smaller, green and purple spikelets. It is distributed from the entire Europe eastwards to central Siberia, southwards to Morocco, Iran, the Himalaya, and central China.

Common quaking-grass, Listed, Bornholm, Denmark. In the background bird’s-eye primrose (Primula farinosa). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flowering common quaking-grass, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bromus Brome

A large genus with about 160 species, widely distributed on all continents, except Antarctica, and it is also absent from certain rainforest and desert areas.

In Ancient Greece, the generic name was applied to a grassy weed, presumably wild oat (Avena fatua, see above). The word bromos means ‘noise’, alluding to the panicles rattling in the wind. Why the name was applied to bromes is not clear.

Bromus hordeaceus Soft brome

Native to all of Europe, except Iceland, and thence eastwards to eastern Siberia, southwards to northern Africa and Central Asia. It has also become naturalized in the Americas, South Africa, Australia, Korea, and Japan. It is very common in Europe, growing along roads, in empty plots and grasslands, and as a weed in fields.

The specific name means ‘resembling Hordeum’ (barley, see caption Cereals below). The common name refers to the soft-haired chaffs of this species.

Soft brome, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Soft brome, Djursland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flowering soft brome, Djursland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bromus ramosus Hairy brome

A large grass, sometimes growing to 2 m tall, with finely hairy leaves, to 50 cm long and 1.5 cm wide, and a long, elegantly drooping panicle. Unlike most other brome species, it grows in shady forests.

It is native from the British Isles, Scandinavia, and Spain towards the south-east, across Turkey, the Caucasus, and Iran to the Himalaya.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with many branches’.

Hairy brome, Møn, Denmark. The young tree is a sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hairy brome, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bromus sterilis Barren brome

This grass, also called poverty brome or sterile brome, is very common, native to the major part of Europe, North Africa, and south-western Asia, eastwards to Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. It grows in a wide variety of open habitats, including waste areas, roadsides, and gardens.

The specific and common names are derogatory, probably indicating that this species is worthless in all respects.

Barren brome, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Barren brome, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Barren brome, Funen, Denmark. The golden leaves in the upper picture are bramble (Rubus fruticosus). (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bromus tectorum Downy brome

Stem to 45 cm tall, with a many-branched, nodding panicle, to 15 cm long. Stem and inflorescence are downy-hairy, awn to 1.8 cm long.

This grass is native to the major part of Europe, eastwards across the Middle East and Central Asia to Mongolia, China, and the Himalaya. It has also become naturalized in many areas across the globe, especially in North America, where it often expels native species and has been declared a noxious weed. It grows in various open habitats and is often among the first colonizers of disturbed areas.

The specific name is derived from the Latin tectum (‘roof’). Presumably, when Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) named this plant in 1753, he heard that it may grow on thatched roofs.

Downy brome, Valnontey, Gran Paradiso National Park, Italy. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calamagrostis Reed-grass, small-reed

This large genus with about 170 species is found on all continents, except Antarctica, but is absent from large parts of South America, Africa, and Tropical Asia.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greel kalamus (‘reed’) and Agrostis (above).

Calamagrostis arenaria Marram grass

This grass, previously known as Ammophila arenaria, is native to coasts of Europe and the Mediterranean. It is a proliferous species, spreading via a network of thick rhizomes, which can grow up to 2 m in six months. If the plant is covered in sand, the rhizomes grow upwards. The rhizomes can withstand submersion in sea water, sometimes drifting with the water to other places, where they may establish new plants.

Today, marram grass is found on coastal sand dunes around the world. At some point, it was introduced to North America, Australia, New Zealand, and other places and planted to prevent coastal erosion. However, it has spread beyond control and is now a serious pest along the Pacific coast of North America, and in New Zealand and western Australia, often expelling native plant species.

The specific name, derived from the Latin arena (‘sand’), as well as the former generic name, derived from Ancient Greek ammos (‘sand’) and philos (‘loving’), both allude to its habitat. The English name is adapted from Old Norse maralmr, from mar (‘sea’) and halmr (‘straw’).

Marram grass has been planted to stabilize dunes, Fanø, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Marram grass, Oregon Dunes, near Eugene, Oregon, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Marram grass, Råbjerg Mile (top), and Mols, both in Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fruiting spikes of marram grass, waving in the wind, Fanø, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Marram grass and biting stonecrop (Sedum acre), Fanø. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calamagrostis canescens Purple small-reed

This plant is distributed from most of Europe eastwards to central Siberia, southwards to the Mediterranean, Caucasus, and Kazakhstan. It is partial to wet meadows.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘slowly becoming grey’, perhaps alluding to the withered inflorescences.

Purple small-reed, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calamagrostis epigejos Wood small-reed

A very widely distributed plant, found from Scandinavia, the British Isles, and Spain eastwards to the Pacific Ocean, southwards to Iraq, Iran, the Himalaya, and northern China, and also in eastern and southern Africa.

One of its favourite habitats is littoral meadows, where it is highly invasive, spreading by its underground rhizomes and often expelling other plants.

The specific name is adapted from the Greek epigaios (‘with a creeping rootstock’).

Wood small-reed, Mols, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wood small-reed, Hagestad Nature Reserve, Skåne, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wood small-reed, Amager, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wood small-reed, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calamagrostis arenaria x C. epigejos Baltic beachgrass, purple marram grass

This hybrid, also known as Ammocalamagrostis baltica, is quite common in dunes around the Baltic Sea, and has also been observed several other places, including Kattegat, northern Denmark/Sweden, and in the British Isles. It can be told from marram grass by the purple inflorescences.

Baltic beachgrass, Dueodde, Bornholm, Denmark. The lighthouse of Dueodde is seen in the background. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Baltic beachgrass, Mols, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Baltic beachgrass, Hagestad Nature Reserve, Skåne, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cenchrus Sandspur, fountain grass

A large genus with about 110 species, found from southern Canada, Greece, Turkey, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and northern China southwards to Chile, Argentina, southern Africa, and Australia. Some species have also become naturalized in Europe. The fountain grasses were formerly placed in the genus Pennisetum.

The generic name is a Latinized form of Ancient Greek kegchros (‘millet-grass’), alluding to the resemblence of some of these plants to certain types of millet. The name fountain grass alludes to the leaves and seedheads of some members, resembling a spray from the base of the plant.

Cenchrus alopecuroides Foxtail fountain grass

This species, by some authorities called Pennisetum alopecuroides, is native from northern China, Korea, and Japan southwards through China, Taiwan, Indochina, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Java to Australia.

Stems erect, to 1 m tall, leaves erect or drooping, to 45 cm long and 1 cm wide. The inflorescence is a silvery-white spike, densely covered in bristles. Later, the spike turns yellow, and when the seeds ripen it turns brown.

The specific name means ‘resembles Alopecurus’ (above), derived from Ancient Greek alopex (‘fox’), oura (‘tail’), genitive urus, and oides (‘resembling’), thus ‘like a foxtail’, alluding to the spike. Other common names include Chinese fountain grass and dwarf fountain grass.

The pictures below are all from Taiwan, where foxtail fountain grass is very common.

Foxtail fountain grass, Taichung (upper 2), and Guoxing. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Close-up of the spike. Malabang National Forest, near Hsinshu, northern Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These plants were photographed in rainy weather on a hill above Nanfangao, a huge fishing harbour south of Yilan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In Taiwan, foxtail fountain grass also grows in cities. This picture is from Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cenchrus echinatus Southern sandspur

If you have once stepped barefoot on the spiny fruits of this grass, you will never forget it. The specific name is derived from the Greek ekhinos (‘hedgehog’), alluding to the fruits, which have lots of sharp spines. This fact is also reflected by its common names, which include spiny sandbur, burgrass, and hedgehog grass.

This species is native to tropical America, but has become naturalized in most tropical and subtropical areas, easily spreading by its spiny fruits, which attach themselves to almost anything. It grows in many different habitats and is regarded as an agricultural weed in 35 countries.

Flowering southern sandspur, encountered in a city park, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Here, southern sandspur is growing next to a busy road in Taichung. The tall plant to the left is horsetail fleabane (Erigeron canadensis). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These pictures from Taichung show the spiny fruits of southern sandspur. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cenchrus setaceus Purple fountain grass

This species, by some authorities called Pennisetum setaceum, forms large clumps of slender, arching leaves, to 60 cm long and 5 mm wide. Leaf sheaths are usually smooth, but sometimes has white hairs along the margin. The inflorescence is a dense, cylindrical, bristly spike, to 35 cm long, the colour varying from light green when young, to white, pink, buff, or purple when maturing.

It is native to northern and eastern Africa, Arabia, and the Near East, but has become naturalized in many other places, and is often regarded as an invasive species, which is a threat to native species. It also tends to increase the risk of wildfires, to which it is well adapted, thus posing a further threat to certain native species.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘bristly’, alluding to the awns.

Purple fountain grass is very common in Gran Canaria, where these pictures were taken. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Purple fountain grass, Point Mugu State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chloris

A genus with about 53 species, distributed in Africa, subtropical and tropical Asia, New Guinea, Australia, and the Americas, except the northern part of North America.

The generic name refers to the goddess Chloris, in Greek mythology the protector of plants.

Chloris barbata Peacock-plume grass

The origin of this plant, also known by the names purple top and swollen fingergrass, is uncertain. Some authorities maintain that it is native to Tropical America, others claim that it is indigenous in Tropical Africa.

Whatever its origin may be, it has been accidentally introduced to most warmer parts of the world and is regarded as an invasive in a number of countries, including Australia, Korea, Thailand, Cambodia, and India.

It is a common weed in sugarcane and rice fields, which is a serious problem, as it is a host of a number of rice insect pests, including white-backed planthoppers (Sogatella furcifera and Sogatodes pusanus), rice bug (Leptocorisa oratorius), rice ear-cutting caterpillar (Mythimna separata), cereal thrips (Haplothrips ganglbaurei and Chirothrips mexicanus), and others.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘bearded’, alluding to the inflorescence.

Peacock-plume grass is extremely common in Taiwan, often covering large tracts of fallow land. This picture shows a huge growth in a fallow plot, Ziguan, north of Kaohsiung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This tuft of peacock-plume grass has taken root in cracks in the asphalt in an abandoned parking lot, Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Close-up of spikes, Fangyuan, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chusquea

This huge genus, comprising about 200 bamboo species, occurs from Mexico and the Caribbean southwards to southern South America.

The generic name stems from Aymara chusque, the name of a bamboo species. Even today, the word survives on several islands in the Caribbean, as the Taino peoples, who once inhabited these islands, originally lived on the mainland, but had to flee.

Chusquea quila Chilean weeping bamboo

This plant is restricted to humid temperate forests of the Andes in Chile and Argentina, where it often forms dense stands, creating an understorey in the forest. It flowers every 10 to 30 years. Seeds and shoots are edible. In former days, Mapuche and Pehuenche peoples made flour from the seeds.

The specific name is a Spanish corruption of cula, the Araucana people’s name of the plant.

Chilean weeping bamboo, Conguillio National Park, Chile. The trees are Chilean monkey-puzzle tree (Araucaria araucana), and the yellow flowers in the foreground are a species of monkeyflower (Erythranthe). (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chilean weeping bamboo, Reserva Nacional Altos de Lircay, Chile. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Coix

This small genus of 3 species is found from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to southern China and Taiwan, and thence southwards to north-eastern Australia.

The generic name is a Latinized form of Ancient Greek koix, according to Greek scholar and botanist Theophrastos (c. 371 – c. 287 B.C.) the name of an Egyptian palm species, from whose leaves various weaved articles were produced. Why Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) linked the name to this grass genus is anybody’s guess.

Coix lacryma-jobi Job’s tears

This plant is native from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to southern China and Taiwan, and thence southwards to Indonesia, but is widely cultivated elsewhere in the tropics and subtropics, often becoming naturalized. The seeds are edible, cooked as grain. In the Far East, a nourishing drink is made from the powdered seeds, and also an alcoholic drink. Necklaces are made from the seeds of hard-shelled varieties. Leaves and stems are used for fodder.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘Job’s tears’. This name, as well as the English names Job’s tears, Christ’s tears, David’s tears, Saint Mary’s tears, tear grass, and Chinese pearl barley, refer to the tear-shaped, pearl-like seeds.

In the Old Testament, Job was a pious man of great virtues, who went through much suffering, as a result of Satan challenging God, saying that he was able to make Job curse God. This made God allow Satan to test Job’s piety through various hardships. Job, knowing that he was innocent, concluded that God must be unjust, but remained faithful to him. The Book of Job, 16:20: “Mine eye poureth out tears unto God.”

At an early stage, Job’s tears was introduced to the United States. To the Cherokee tribe, its seeds became known as Cherokee corn beads, being used for adornment since at least the time of the foundation of the Cherokee Nation (1794). During the forced removal of c. 16,000 Cherokee, in 1838, from their home lands in south-eastern U.S. to present-day Oklahoma, an estimated 4,000 died. Legend has it that Cherokee corn beads sprang up along the various migration routes, called ‘The Trail of Tears’, or, in Cherokee, Nunna daul Isunyi (‘The trail where we wept’).

Job’s tears, naturalized in a dried-out riverbed, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cortaderia

A genus with about 20 species, found from Central America to the southern part of South America. One species, C. selloana (below), is widely cultivated as an ornamental, but it readily escapes and has become a troublesome weed in many places.

The generic name is derived from Spanish cortadera (‘machete’), alluding to the leaves of these grasses, which have very sharp edges.

Cortaderia araucana

This grass, growing to 2 m tall, is found in central and southern Chile, and in southern Argentina, growing at elevations between 300 and 2,000 m. It prefers humid areas with almost constant rainfall.

The specific name refers to the Araucanians, a former local tribe in Chile.

Cortaderia araucana, growing in an old lava flow from the Llaima volcano, Conguillio National Park, Chile. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cortaderia selloana Pampas grass

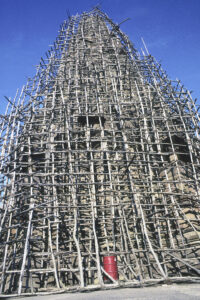

This huge grass species, which may grow to a height of 3 m, is native to southern South America, named after the Pampas region. It has been introduced as an ornamental plant, and also as animal feed, to numerous other areas, including southern Europe, the United States, China, Australia, and New Zealand. When dried, the plumes are widely used in flower arrangements, and in China, the strong stems have been used in the construction of kites.

Pampas grass is very adaptable, and a single plant can produce over one million seeds during its lifetime. As a result, it has become invasive in many places, including New Zealand, Florida, California, Hawaii, South Africa, and Spain.

The specific name honours German naturalist Friedrich Sellow (originally Sello) (1789-1831), who stayed in Brazil and Uruguay 1814-31, where he collected a huge number of plants new to science. In 1831, he drowned in Rio Dolce, only 42 years old.

Pampas grass is highly invasive in New Zealand. These pictures were taken on the Karikari Peninsula (top) and near Trouson Kauri Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Corynephorus

A small genus with 7 species, distributed from Scandinavia and Scotland southwards to northern Africa, eastwards to European Russia, the Caucasus, and Iran.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek koryne (‘club’) and phoros (‘bearing’), referring to the shape of the awn.

Corynephorus canescens Grey hair-grass

A tufted, reddish or bright green grass, growing in sandy soils, often on older dunes near the coast. It is native to Europe, from Scandinavia and England eastwards to the western part of European Russia, southwards to Morocco, Italy, and Romania. In North America, it was introduced as an ornamental and has become naturalized several places.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘slowly becoming grey’, perhaps alluding to the withered inflorescences.

Inland sand dune with grey hair-grass, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grey hair-grass and a species of reindeer lichen (Cladonia), Fanø, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Inflorescences of grey hair-grass, Fanø. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Morning dew in grey hair-grass, Ho Bugt, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cynosurus Dog’s-tail

This genus with about 11 species occurs in Europe, except Iceland, eastwards to the western part of European Russia, southwards to northern Africa, Arabia, Iran, and Turkmenistan.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kyon (‘dog’), genitive kynos, and oura (‘tail’), genitive urus, referring to the shape of the spike.

Cynosurus cristatus Crested dog’s-tail

This species, which is more or less tufted, is easily identified by the flattened spikes. It grows on rich, rather dry soils, and avoids extremes of pH.

It is found in Europe, except Iceland, eastwards to the western part of European Russia, southwards to the Mediterranean and Iran. It has also become naturalized in other parts of the world, including the Americas, Australia, and New Zealand.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘crested’, alluding to the shape of the spikelet (see picture at the beginning of this page).

Flowering crested dog’s-tail, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Crested dog’s-tail, Fanø, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dactylis Cock’s foot, orchard grass

Today, only 2 species are accepted in this genus, the widespread D. glomerata (below), and D. smithii, which is restricted to Madeira, the Canary Islands, and the Cape Verde Islands.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek daktylis, a kind of grape with finger-shaped bunches. In a botanical context, the word refers to an inflorescence, which is divided into finger-like sections.

Dactylis glomerata Common cock’s-foot

One of the few grasses with a flat stem, this tussock-forming species grows to 1.4 m tall. Leaf sheaths are strongly keeled, blade flat, greyish-green, to 50 cm long and 9 mm wide, surface rough to the touch. The inflorescence is a large panicle, branches to 15 cm long, ending in distinctive triangular spikelets to 9 mm long, florets green or purplish, anthers white or yellow. It grows in a variety of habitats, including roadsides, grasslands, and waste plots, ssp. lobata also in forests.

It is widely distributed, from Iceland eastwards to central Siberia, southwards to northern Africa, Sri Lanka, China, and Taiwan, but as it is an important fodder plant, it has been widely introduced to temperate and subtropical regions throughout the world. and has become naturalized in many places. In some areas, it is considered an invasive species. In the northern regions, it grows down to sea level, in the southern parts restricted to mountains. In the Himalaya, it may be found at altitudes between 2,500 and 4,000 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘up-rolled’, in this case referring to the clustered spikelets.

Common cock’s-foot in morning fog, Store Hjøllund Plantation, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Common cock’s-foot, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Common cock’s-foot with raindrops, Winnekenni Park Conservation Area, Haverhill, Massachusetts, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wood cock’s-foot, ssp. lobata, Jutland, Denmark. This subspecies is partial to forests. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Deschampsia Hair-grass, tussock grass

This genus, comprising about 62 species, is found on all continents, with D. antarctica being one of only two flowering plants native to Antarctica. However, the genus is absent from large parts of South America, Africa, Tropical Asia, and Australia.

The generic name honours French surgeon and naturalist Louis Auguste Deschamps (1765-1842). He was physician on board the French frigate L’Esperance, which, with other ships, set sail in 1791 in search of another ship, La Perouse, which had vanished in Oceania. However, the search was in vain, and L’Esperance was also haunted by misfortunes. Of its 119 crew members, 89 died, including the captain, and the ships were seized by the Dutch in Dutch East India (today Indonesia). Deschamps remained in Java until 1802, exploring the local flora and fauna.

Deschampsia cespitosa Tufted hair-grass

The leaves of this tussock grass are very characteristic, having many white, longitudinal nerves, clearly seen against the light. The upper surface and edge have tiny, forward-pointing teeth, feeling rough in one direction, smooth in the other.

It grows to about 1.4 m tall, found in various types of grassland, preferably in humid areas. It is very widespread in the Northern Hemisphere, southwards to Mexico, Iran, and China, and it is also found in montane areas of the central parts of Africa, and in eastern Australia.

The specific name is derived from the Latin caespes (‘lump’), in a botanical context referring to a tussock.

Tufted hair-grass, Vitranc, near Kranjska Gora, Slovenia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tufted hair-grass is easily identified by the leaves, which have clear white nerves. – Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Withered inflorescences of tufted hair-grass, Funen, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Deschampsia flexuosa, see Avenella flexuosa.

Eleusine

This genus, containing about 10 species, is found in Africa, Madagascar, warmer parts of Asia, and the southern half of South America.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek Eleusis, the name of a town, in which initiation rites in a cult centered around the goddesses Demeter and Persephone took place. This cult is believed to have been based on an older agrarian cult.

Eleusine indica Indian goosegrass

This species, also called by other names, including yard-grass, wiregrass, and crowfoot-grass, is a close relative of the cultivated finger millet (E. coracana, see caption Cereals below). Like that species, its kernels are edible, but due to their tiny size, the yield is too low to be worth the effort. Instead, it has become a most troublesome weed in cultivated fields, and also on lawns and golf courses. A single plant may produce more than 50,000 seeds, which can be easily dispersed by wind and water, or attached to animal fur or machinery.

Indian goosegrass, which is possibly a native of warmer areas of Africa and Asia, is considered a “serious weed” in at least 42 countries. Besides being an agricultural weed, it also invades forests margins, grasslands, marshes, river banks, and road sides. Currently, it is listed as invasive in several countries in Europe, Asia, Central and South America, and the Caribbean, and on many islands in the Pacific Ocean. (Sources: cabi.org/isc/datasheet/20675; L.G. Holm et al. 1977. The World’s Worst Weeds. Distribution and Biology. University Press of Hawaii)

Large growth of Indian goosegrass, Tunghai University Park, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Elymus Couch grass, wild rye

The native range of this large genus, counting about 180 species, is temperate and subtropical areas of the Northern Hemisphere, Ethiopia, and Central and South America.

The generic name is a Latinized form of Ancient Greek elymos (‘millet’).

Elymus caninus Bearded couch grass

This species grows in forests, from Iceland eastwards to eastern Siberia, southwards to the Mediterranean, Iran, the Himalaya, Kazakhstan, and Xinjiang.

The specific name is derived from the Latin canis (‘dog’), a derogatory term, indicating that this grass is worthless to people.

Bearded couch grass, growing next to a moss-covered tree stump, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bearded couch grass, Funen, Denmark (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bearded couch grass, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flowering bearded couch grass, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Elymus repens Common couch grass

This grass, previously known as Elytrigia repens or Agropyron repens, is a native of Eurasia and north-western Africa, but has become naturalized in many other areas, where it is often regarded as an invasive plant. It is an extremely troublesome weed in fields and gardens, as just a tiny bit of underground stem is able to produce a large colony of plants, sending up stems at regular intervals.

The specific name means ‘creeping’ in Latin, referring to the creeping rhizome, and the common name quick-grass alludes to its fast growth. The former generic name Elytrigia is derived from the Greek eletryon (’cover’) and tryge (’corn crop’), referring to the habit of couch grass to ‘hide’ in crops.

The common name dog’s grass stems from the habit of dogs to chew its leaves in order to procure vomiting. In former days, it was believed that the leaves would cure sick dogs. English herbalist Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654) says: ”If you know it [couch grass] not by this description, watch the dogs when they are sick and they will quickly lead you to it.”

Greek physician, pharmacologist, and botanist Pedanius Dioscorides (died 90 A.D.), who was the author of De Materia Medica, five volumes dealing with herbal medicine, asserts that a decoction of the rhizomes is a useful remedy as a diuretic and for bladder stones. English herbalist John Gerard (c. 1545-1612) writes: “Although that couch-grasse be an unwelcome guest to fields and gardens, yet his physicke virtues do recompense those hurts; for it openeth the stoppings of the liver and reins without any manifest heat.”

Flowering common couch grass, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord (top), and Roskilde Fjord, Zealand, both in Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Close-up of the spike, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Festuca Fescue

A huge genus with around 650 species, widely distributed on all continents, except Antarctica, and it is also absent from certain rainforest and desert areas.

The generic name is Latin, probably meaning ‘grass straw’. The English name is a corruption of the Latin name.

Festuca altissima Wood fescue

This species occurs from Scandinavia and the British Isles eastwards to central Siberia, southwards to the Mediterranean, Iran, and Kazakhstan. It is gregarious, forming many-leaved tussocks, leaves evergreen, up to 50 cm long, pointing upwards and only slightly drooping at the apex.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘tall’.

Wood fescue, central Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Festuca arundinacea, see Lolium arundinaceum.

Festuca gigantea, see Lolium giganteum.

Festuca rubra Red fescue

This species is very adaptable, growing in most open habitats, including beaches and dunes, and it has also adapted to a life in cities. It is widespread across much of the temperate and subarctic areas of the Northern Hemisphere, southwards to Mexico, northern Africa, Iran, the Himalaya, and southern China.

It is cultivated as an ornamental plant, used for lawns and as groundcover.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘red’, alluding to the reddish spikelets.

Field of cultivated red fescue, Vitlycke, Bohuslän, Sweden. Strong wind or rain has bent most of the plants to the ground. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red fescue, growing along a water front at Lake Mälaren, central Stockholm, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Festuca vivipara Viviparous fescue

This grass is found in subarctic areas around the globe, and also in the British Isles, the Alps, and Kamchatka. It is a small plant, growing in dense tufts to 20 cm tall.

The generic and common names are derived from the Latin vivus (‘living’) and parus (‘to give birth’), thus ‘the one who has living offspring’, alluding to the spikelets sprouting while still on the plant.

Viviparous fescue in evening light, Aðaldal, northern Iceland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Glyceria Sweetgrass

This genus, comprising about 40 species, is found on all continents, except Antarctica, but is absent from large parts of South America, Africa, and Tropical Asia.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek glykeros (‘sweet’), alluding to the edible, sweet grains of these plants.

Glyceria fluitans Floating sweetgrass

This species, also called water manna-grass, grows in very wet habitats, along rivers and in ponds. It has a creeping rootstock and a thick stem to 1 m tall, leaves bright green, to about 25 cm long, folded at first, then becoming flat. It is remarkable by being able to develop floating leaves, which may sometimes form mat-like growths on the surface.

It is found all over Europe, eastwards to the Ural Mountains, southwards to Morocco, Turkey, and Turkmenistan.

In former times, this plant was cultivated for the grains, which were cooked and eaten as a kind of porridge, hence the name ‘manna-grass’.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘floating’, referring to the floating leaves.

Floating leaves of floating sweetgrass, Bornholm (top), and north of Horsens, both in Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Inflorescence of floating sweetgrass, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Glyceria maxima Reed-sweetgrass

A large grass, stem erect, to 2 m tall, leaves bright green, to 60 cm long and 2 cm wide. The inflorescence is a panicle, to 45 cm long, many-branched. It is mainly growing in eutrophic reedbeds.

It is native to Europe, with the exception of Iceland and the Iberian Peninsula, eastwards to western Siberia, southwards to Kazakhstan and Xinjiang. It has also become naturalized elsewhere, including North America, Australia, and New Zealand, and is regarded as an invasive plant in many areas.

Like the previous species, the seeds are edible, with a sweet taste.

Reed-sweetgrass, growing at the edge of a mill pond, north of Horsens, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Reed-sweetgrass, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gynerium sagittatum White cane

This vigorous species, in Spanish known as caña blanca, caña brava, and many other names, grows to 6 m tall, often forming very dense growths. It is the only member of the genus, found from Mexico southwards to northern Argentina.

In Columbia, sombreros are made from the straw, and in Brazil it is made into trellises for climbing plants (such as beans) and tomatos. The plant was formerly used in traditional medicine.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek gyne (‘woman’) and erion (‘wool’), alluding to the glumes of the spikelets bearing long hairs. The specific name is derived from the Latin sagitta (‘arrow’), referring to the shape of the leaves.

White cane, Volcán Arenal National Park, Cordillera de Tilarán, Costa Rica. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hesperostipa

A small genus with 5 species, widely distributed in North America and northern Mexico. They were previously included in the genus Stipa, which has since been divided into a number of genera, including Stipellula (below).

The generic names is derived from Ancient Greek hesperos (‘western’).

Hesperostipa comata

This plant is widespread in North America, from southern Canada southwards to northern Mexico, eastwards to the Great Lake area. It is especially common in the western third of the continent, growing in many habitat types, including grasslands, pine and juniper forests, and sagebrush scrubland.

It forms small tussocks, stem erect, to 1 m tall, inflorescence to 28 cm long. At maturity, the awn twists into a large spiral, to 20 cm long, giving rise to the popular name needle-and-thread grass, as it sometimes resembles a threaded sewing needle.

The specific name is derived from the Latin coma (‘hair’), alluding to the long, hairy awn.

Hesperostipa comata, Wupatki National Monument, Arizona, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hierochloe odorata, see Anthoxanthum nitens.

Holcus lanatus Meadow soft-grass

This common species, also known as velvet grass, was named due to its velvety, grey-green leaves. It grows to about 60 cm tall, forming tufts, stem erect or ascending, downy, reddish or violet near the base, leaf sheaths slightly inflated.

It is distributed in Europe, from Ireland and Portugal eastwards to western Russia and the Caucasus, and from Scandinavia southwards to northern Africa, but has been widely introduced elsewhere as a pasture grass. In North America, it is considered an invasive species.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘woolly’, alluding to the downy stem and leaves.

Meadow soft-grass, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Inflorescences of meadow soft-grass, bent down by a rain shower, Fanø, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Holcus mollis Creeping soft-grass

This grass often forms dense growths, spreading by underground rhizomes. It is partial to nutritious-poor soils, growing in open forests and along forest edges, and sometimes in open areas. Stem to 50 cm tall, furrowed, hairy on the nodes.

It is distributed in Europe, from Ireland and Portugal eastwards to western Russia, and from Scandinavia southwards to northern Africa and Greece.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘soft’, alluding to the downy stem and nodes.

Creeping soft-grass, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hordeum Barley

This genus contains about 34 species, native to temperate and subtropical areas of the Northern Hemisphere, and also to South America and southern Africa.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for barley, derived from Proto-Italic horzdeom (‘bristly’), alluding to the long, prickly awns of these plants.

Hordeum jubatum Squirreltail barley, foxtail barley

This species is native to the entire North America, and from western Siberia eastwards to the Pacific, southwards to the Caucasus, Tadzhikistan, and north-eastern China. Elsewhere, it is grown as an ornamental plant, and has become naturalized in many places.

The stem is erect, to 1 m tall, smooth, leaf sheaths split and hairy, inflorescence a nodding spike, each spikelet having 7 awns, to 8 cm long, with upward-pointing barbs, which easily get attached to an animal fur or people’s clothes, thus spreading the seeds.

In former days, the Kawaiisu people pounded the seeds for food, and they used the entire plant as a tool to rub the skin off yucca stalks. The Chippewa and Potawatomi used the root medicinally.

The specific name is derived from the Latin iuba (‘mane’ or ‘crest’), like the common names alluding to the bushy awns.

Squirreltail barley, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hordeum murinum Wall barley

Wall barley, also called false barley, is native to central and southern Europe, eastwards to the Ural Mountains and Kazakhstan, southwards to northern Africa, Arabia, and north-western Himalaya. It grows along roads, as a weed in fields, and in waste plots. It has readily adapted to a life in cities.

The stem is unbranched, to 40 cm tall, spikes pale green or yellowish, spikelets in groups of 3, awn short, to 2 cm long, pointing outward at maturity.

The specific name is derived from the Latin murus (‘wall’), alluding to the fact that this plant often grows along stone fences and house walls.

Unripe spikes of wall barley, Frederiksø, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pale spikes of wall barley stand out against a dark house wall, Rønne, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wall barley, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wall barley, Rodopos Peninsula, Crete. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Koeleria

This genus, comprising about 73 species, is found on all continents, except Antarctica, but is absent from large parts of South America, Africa, Tropical Asia, and Australia.

The generic name commemorates German physician and botanist Georg Ludwig Koeler (1764-1807), who began botanical studies in 1786. His goal was to write a work named Flora von Deutschland, Frankreich und der Schweiz (‘Flora of Germany, France, and Switzerland’). However, only the chapter on grasses was published. His untimely death during a typhoid epidemic in 1807 put an end to his work.

Koeleria pyramidata Crested hair-grass

This plant often forms loose tufts, stem to 90 cm tall, downy above and on the sheaths, leaves to 24 cm long and 5 mm wide, inflorescence a spike to 20 cm long.

It is distributed from England, Denmark, and the Baltic countries eastwards to eastern Siberia, southwards to the Mediterranean, Iran, and western Himalaya. Previously, it was thought that it also occurred in North America, but today plants here are regarded as a separate species, prairie junegrass (K. macrantha).

The specific name probably alludes to the inflorescence.

Crested hair-grass, Aggersund, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lagurus ovatus Hare’s-tail grass

This striking grass, the only member of the genus, is native to all countries around the Mediterranean, on Crimea, in the Caucasus and Arabia, and on the Azores, Madeira, and the Canary Islands. It is widely cultivated and has become naturalized in various countries in Europe and the Americas, and also in South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and elsewhere.

It is a tuft-forming species, growing to 50 cm tall, with pale green leaves and numerous short, ovate inflorescences, which turn buff or white when ripe.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek lagos (‘hare’) and oura (‘tail’), genitive urus, referring to the fluffy inflorescence. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘ovate’, alluding to the shape of the inflorescence.

Hare’s-tail grass, near Karasu, Black Sea, Turkey. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hare’s-tail grass, naturalized in Point Lobos State Reserve, Big Sur, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Leymus

A genus with about 56 species, is found in subarctic, temperate, and subtropical regions of the Northern Hemisphere, southwards to northern Mexico, Pakistan, and southern China, with an isolated occurrence in the southern Andes.

The generic name is an anagram of Elymus, which is a Latinized form of Ancient Greek elymos (‘millet’).

Leymus arenarius Lyme grass

This large grass grows in sandy areas along the coasts of Europe, from north-western Russia westwards to Iceland, and thence southwards to Spain, Greece, and Ukraine. A closely related species, Leymus mollis, previously regarded as a subspecies of lyme grass, is native along subarctic and temperate coasts of North America and north-eastern Asia.

Lyme grass is easily identified by the blue-green leaves, to 1 m long and 1.5 cm wide, and the heavyset stem, to 1.5 m tall, with a spike to 30 cm long. The sheath is short, about 1 mm, and hairy along the edge. The plant has many runners and often form large growths.

The seeds are edible when cooked, but are hardly worth the effort, as they are hard to extract from the chaff.

The specific name is derived from the Latin arena (‘sand’), alluding to its habitat.

Lyme grass, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The last sun rays of the day illuminate flowering spikes of lyme grass, Nature Reserve Vorsø. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lolium Ryegrass, fescue

A genus with around 28 species, occurring in northern Africa and the entire Eurasia, except the tropical south-eastern parts. Following genetic research, some species of fescue (Festuca) have been moved to this genus.

The generic name is derived from Indo-European lol (‘making sleepy’ or ‘lull to sleep’). In Ancient Rome, it was the name of a much feared weed, probably poisonous darnel (Lolium temulentum), by Roman poet Publius Vergilius Maro (70-19 B.C.), in English known as Vergil, described as “the evil-bringing Lolium.” It was often infested with fungi that produce a toxic alkaloid, temulin, which causes dizziness, confusion, and blurred vision. The seeds were often ground to powder and mixed with alcohol to enhance the intoxication. Traces of temulin has been found in Egyptian graves from about 2500 B.C.

It may also be this plant that is referred to as tare in Matthew, 13:30: “Let both grow together until the harvest, and in the time of harvest I will say to the reapers: Gather ye together first the tares, and bind them in bundles to burn them; but gather the wheat into my barn.”

Lolium arundinaceum Tall fescue

This plant, also known as Festuca arundinacea, is found in humid grasslands, and along rivers and coasts. It occurs from Scandinavia and the British Isles eastwards to western Siberia, southwards to northern Africa, Iran, north-western Himalaya, and Xinjiang. It is widely cultivated elsewhere as a fodder plant and has become naturalized in many parts of the world.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek arundo, the classical name of giant reed (Arundo donax, above), but it may also mean ‘reed’ in general, thus ‘reed-like’.

Tall fescue, Mols (top), and Zealand, both in Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Inflorescence of tall fescue with spider webs, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stems and leaves of tall fescue, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lolium giganteum Giant fescue

This plant, also known as Festuca gigantea, is widely distributed, from the British Isles and Scandinavia eastwards to central Siberia, southwards to the Mediterranean, Iran, the Himalaya, and central China. It mainly grows in forests and along forest edges.

As its name implies, it is a large species, forming loose tufts, stem to 1.5 m tall, sometimes even more, the broad leaves and panicles gracefully arched. At the base of the leaf, conspicuous sickle-shaped, brownish teeth surround the stem.

Giant fescue, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lolium multiflorum Italian ryegrass

Stem erect, to 90 cm tall, leaves alternate, to 20 cm long and 8 mm wide, smooth and shining, with auricles at the base. Spike to 20 cm long, spikelets arranged with the narrow side towards the stem (as opposed to the rather similar spikelets of couch grass (Elymus repens, above), which have the flat, broad side towards the stem). It may be told from the very similar perennial ryegrass (below) by the much longer awns, and by the rachis, which often undulates strongly between the spikelets. It mainly grows in disturbed habitats, including grasslands, roadsides, fields, and waste areas.

Its native area is probably from southern Europe eastwards to Kazakhstan, southwards to northern Africa, Iran, and western Himalaya. However, it has been cultivated as a fodder plant for centuries, and today it has become naturalized in most parts of the world. In some areas, it is regarded as a noxious weed in fields, and as an invasive species in other habitats.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘many-flowered’.

Flowering Italian ryegrass, cultivated on Møn, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lolium perenne Perennial ryegrass

This grass forms tufts, stem to 90 cm tall, leaves narrow and shining, to 20 cm long and 6 mm wide. Like in the previous species, the spikelets turn the narrow side towards the stem. Awn is absent or very short.

It is native to Europe (except Iceland), eastwards to central Siberia, southwards to northern Africa, Iran, and the Himalaya. At an early stage, it was introduced to most other parts of the world as a fodder plant, to stabilize soil, and for lawns and golf courses.

Flowering perennial ryegrass, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Perennial ryegrass with withering flowers, Svaneke, Bornholm. In the background biting stonecrop (Sedum acre). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Melica Melick

This genus, counting around 90 species, is found in temperate and subtropical areas of the Northern Hemisphere, southwards to northern Mexico, northern Africa, Arabia, and southern China, and also in western and southern South America and southern Africa.

The generic name has been explained in various ways. In the Latin, melica means ‘buckwheat’, and the spikelets of wood melick (below) somewhat resemble buckwheat seeds. Another explanation is that the name derives from Ancient Greek meli (‘honey’), alluding to the stem, which has a sweet taste.

Melica ciliata Hairy melick

A tufted plant, spreading by rhizomes, stem erect, to 1 m tall, leaves flat, stiff, to 15 cm long and 3 mm wide, sheaths tubular and closed, ligule membraneous. Inflorescence a spike-like panicle, to 20 cm long, strongly hairy at maturity.

It is found from south-eastern Sweden, southern Finland, the Baltic countries, and Germany southwards to northern Africa, and from France and Spain eastwards to Kazakhstan, Xinjiang, and Iran.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘hairy’, alluding to the hairy spikes.

Gravel beach with hairy melick, its seedheads waving in a strong wind, Äleklinta, Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

As the sun sets, the fruiting spikes of hairy melick change colour. – Öland, Sweden. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Close-up of inflorescences, Stora Alvaret, Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Melica nutans Mountain melick

This plant, to 70 cm tall, is easily identified by the one-sided, nodding inflorescence with 5-15 fertile, oblong and compressed spikelets, florets elliptic, to 5 mm long.

It is very widely distributed, from England eastwards to Kamchatka, and from Scandinavia and Siberia southwards to the Mediterranean, Tibet, and China, growing in forests and other shady places, at elevations up to 2,300 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘nodding’, alluding to the inflorescence.

Mountain melick, Hansted Skov, north of Horsens, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Melica uniflora Wood melick