Mammals in the Indian Subcontinent

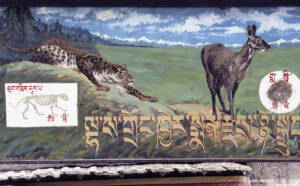

This male alpine musk deer (Moschus chrysogaster) is enjoying his meal of old-man’s-beard lichens (Usnea), which have fallen to the ground in the forest below the Tengboche Monastery, Khumbu, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

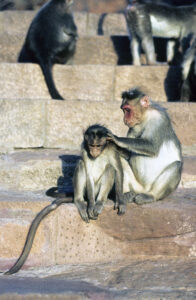

Female rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta), enjoying the evening sun in Sariska National Park, Rajasthan. The one in front is suckling its young. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

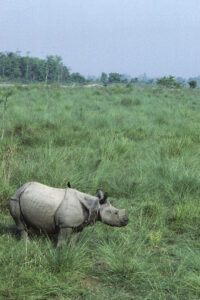

Greater one-horned rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) in Kaziranga National Park, Assam – one of the few strongholds of the species. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Five-striped palm-squirrel (Funambulus pennantii) with nesting material, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Himalayan tahr (Hemitragus jemlahicus) males, grazing in the Khumbu area, eastern Nepal, where this species is common. The animals are not harmed by the local Buddhist Sherpas. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Asian elephant (Elephas maximus), using the trunk to spray mud on its body. The purpose is probably to cool down, and perhaps the mud cake also protects its skin against stinging insects. – Yala National Park, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Royle’s pika (Ochotona roylei), encountered at Phedi, near Gosainkund, Langtang National Park, central Nepal, was remarkably confiding, scurrying about between our feet. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Northern plains langurs (Semnopithecus entellus), silhouetted against the light, Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This page deals with a selection of mammals, which I have encountered during my travels in the Indian Subcontinent since 1974. Families, genera and species are presented in alphabetical order.

Tibet (called Xizang by the Chinese), Qinghai, and Xinjiang are treated as separate areas. The term ‘western China’ indicates Chinese territories just east of Tibet and Qinghai. The term ‘south-western China’ includes the provinces Yunnan, Guizhou, and Sichuan.

As is obvious from most of the pictures below, I like to show the animals in their natural surroundings, or studies of their behaviour.

In case you find any errors on this page, I would be grateful to receive an email. You may use the address at the bottom of the page.

Map, showing Indian states and union territories. (Borrowed from www.mapsofindia.com)

Bovidae

This large family, comprising about 47 genera and c. 143 species, are cloven-hoofed, ruminant animals, including cattle, antelopes, sheep, goats, and many others. Members occur in Eurasia, Africa, and North America, and the water buffalo (below) has become feral in Australia.

Many species of antelope are presented on the page Animals – Mammals: Antelopes.

Antilope cervicapra Blackbuck

The male of this species is a wonderful creature: coal black, with white markings on face, legs and belly, and long, straight, spiralled horns, growing to 65 cm long in some individuals. During territorial battles, the males spar with their horns, trying to gather as many females as possible for their harem. Females and young males have more subtle colours, being brown and white.

Formerly, this gorgeous animal was distributed all over plains and semi-deserts in India and Pakistan, but uncontrolled hunting by British and Indian ‘sportsmen’ (as they were fond of calling themselves), and competition from grazing cattle, goats and sheep, took their toll.

The blackbuck disappeared completely from Pakistan, and from most of India. Larger herds survived only in the states of Rajasthan and Gujarat, mainly because the animals were protected by the Bishnoi and other local peoples. Traditionally, they protect all wild animals, even allowing them to graze in their fields of wheat and lentils. Thanks to their protection of the blackbuck, biologists have been able to re-introduce the species to many locations in India.

The blackbuck also plays a role in Hindu mythology, where the chariot of the moon god Chandrama is pulled by this animal.

The specific name is derived from the Latin cervus (‘deer’) and capra (‘she-goat’), thus ‘deer-goat’.

At the outskirts of the town of Mamallapuram, Tamil Nadu, a huge sculpture, measuring c. 15 by 30 m, has been carved into two boulders. The main theme of this sculpture, which has been dubbed The Descent of the Ganges, is an event in the Hindu epic Mahabharatha. Bhagiratha was a great king, doing penance for a thousand years to obtain the release of his 60,000 great-uncles from the curse of Saint Kapila, eventually leading to the descent of the goddess Ganga to Earth, in the form of River Ganges. However, many other themes have been included in the sculpture, including animals like elephants, cats, and blackbuck.

My difficulties to obtain permission to photograph blackbuck in Tal Chapar Wildlife Sanctuary are related on the page Travel episodes – India 1979: Hunting blackbuck with camera.

Adult male blackbuck, Gudi, near Osiyan, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sub-adult males with brownish parts, Gudi. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Females and sub-adult males, Gudi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Adult male, Tal Chapar Wildlife Sanctuary, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

An adult male shows a threatening attitude towards another male, which runs away, Tal Chapar Wildlife Sanctuary. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Younger males, Tal Chapar Wildlife Sanctuary. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Blackbuck, Velavadar National Park, Gujarat. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Blackbuck at a waterhole, Velavadar National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Detail of the sculpture ‘The Descent of the Ganges’ (see text above), depicting blackbuck. – Mamallapuram, Tamil Nadu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Boselaphus tragocamelus Nilgai

This large, stout antelope, the only member of the genus, is distributed in the major part of India, and there is also a small population in southern Nepal. It is especially common in Rajasthan.

The name nilgai is Hindi, meaning ‘blue cow’, which refers to the slate-coloured, slightly bluish coat of the male, and to its similarity to the sacred cow. For the latter reason, the nilgai is protected by devout Hindus and has thus escaped the fate of many other animals in India, which are on the brink of extinction, such as the tiger (below), the lion (Panthera leo), and the blackbuck (above). The coat of females and young animals is a pale sandy brown. Both sexes have a white throat patch.

The scientific name of this antelope is quite peculiar. It is derived from four Greek words, bous (‘cow’), elaphos (‘deer’), tragos (‘goat’), and kamelos (‘camel’). The name was applied by Prussian naturalist Peter Simon Pallas (1741-1811), to whom this antelope apparently resembled a mixture of these four animals.

The slate-coloured, slightly bluish coat of the male nilgai, and its similarity to the sacred cow, have given rise to its name, which means ‘blue cow’ in Hindi. This bull was photographed in Sariska National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cows and calves are pale brown with white chin and upper neck. Note the typical black-and-white markings on the ears. – Sariska National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nilgais, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nilgais, running across a swamp, Keoladeo National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Resting nilgai bull, Keoladeo National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bull, greeting a young animal, Keoladeo National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nilgais, drinking from a waterhole, Sariska National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A cow and a younger animal, drinking from a waterhole, Sariska National Park. A rufous treepie (Dendrocitta vagabunda) is sitting on the back of the young animal. Peafowl (Pavo cristatus) are also present. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bubalus Asian buffaloes

This genus contains 4 or 5 species, the wild water buffalo (below), the tamaraw (B. mindorensis), found on the island Mindoro in the Philippines, the lowland anoa (B. depressicornis) and the mountain anoa (B. quarlesi), which are both restricted to Sulawesi, and finally the domestic water buffalo (below), which has no genuine wild populations, but feral populations exist in South America, Australia, and Sri Lanka.

The generic name is a Latinized version of Ancient Greek boubalos, the classical word for buffaloes.

Bubalus arnee Wild water buffalo

This magnificent animal is restricted to a few locations in north-eastern and central India, the Kosi Tappu Reserve in southern Nepal, and a single place in each of the countries Myanmar, Thailand, and Cambodia. It is believed that the global population is less than 3,400 individuals, of which about 3,100 live in India, mainly in Assam. As it is still declining, it has been listed as Endangered in the IUCN Red List.

The specific name is the Hindi name of this animal, also spelled arni.

Wild water buffaloes, Kaziranga National Park, Assam. The bird is a cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bubalus bubalis Domestic water buffalo

Research indicates that this animal most probably descended from the wild water buffalo. It was domesticated about 5,000 years ago, and today it is so different from the wild species that most authorities regard them as separate species.

The main difference between the two lies in the shape of the horns, which in the wild species are massive, spreading out sideways almost horizontally, only curving at the tip, whereas the horns of the domestic animals are smaller, curved almost from the base.

Traditionally, the water buffaloes, which live in the wild in several national parks in Sri Lanka, were regarded as wild buffaloes, but in all probability they descended from feral domestic buffaloes, as their horns are smaller than those of the genuine wild buffaloes in Assam.

Feral water buffaloes, Yala National Park, Sri Lanka. The bird to the right is a little egret (Egretta garzetta). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Water buffaloes, cooling off in water, Yala National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Water buffalo, enjoying a mudbath, Yala National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This calf in Yala National Park is unusually pale. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In Hindu mythology, Mahishasura was a powerful demon, who threatened the power of the gods, and not even the mighty gods Vishnu and Shiva could resist him. Then Durga, Shiva’s shakti (female aspect), took action. Riding on her lion, she attacked Mahishasura, who first changed into a huge buffalo, then into a lion. Durga sliced off his head, but he then changed into an elephant, whereupon Durga cut off his trunk. The demon hurled large mountains at the goddess, but, nevertheless, she managed to kill him with her spear.

Durga and other Hindu gods are described on the page Religion: Hinduism.

This sculpture in the great temple near Aihole, Karnataka, depicts Durga, riding on her lion, battling against Mahishasura, here in the shape of a buffalo. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Capra Goats

This genus contains about 9 species, including the domestic goat and several species of ibex. The domestic goat is presented in depth on the page Animals: Animals as servants of Man.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for a she-goat. A billy-goat was called caper.

Capra sibirica Siberian ibex

In former times, this goat was treated as a subspecies of the Alpine ibex (Capra ibex), and whether it is specifically distinct from other ibex is still not entirely clear. Traditionally, 4 subspecies have been recognized, but some authorities regard it as monotypic. In the Himalaya, subspecies sakeen occurs in Pakistan and north-western India, and it is also found in Afghanistan and the Pamir Mountains.

The Siberian ibex is a heavily built animal. Males measure 90-110 cm across the shoulder, weighing 60-130 kg, with horns typically about 115 cm long, although a length up to 148 cm has been recorded. Females are smaller, measuring 70-90 cm across the shoulder, weighing 35-56 kg, with horns measuring an average of 27 cm long. Both sexes also possess a scent gland beneath the tail. Their greyish coat is well suited for camouflage in mountains with low or no vegetation.

This picture is from the interesting Hindu temple Hadimba in Manali, Himachal Pradesh, which is adorned with various items, including ringed horns of Siberian ibex, smooth horns of bharal (Pseudois nayaur, see below), and antlers of Kashmir stag (Cervus hanglu ssp. hanglu, see below). The history behind this temple is described on the page Religion: Hinduism. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Near Saspol, Ladakh, many of the boulders, which lie helter-skelter in the desert, are covered in petroglyphs, depicting various items, including ibex, hunters, birds, and stupas – artwork by an unknown people and of unknown age. The black surface on these boulders is called desert varnish. It consists of a thin layer of manganese and clay, formed through thousands of years by bacteria, living on the rock surface. These bacteria absorb small amounts of manganese from the atmosphere and deposit it on the boulders. The petroglyphs have been made by scraping off this ‘varnish’ from parts of the surface.

(Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

My beloved is like a gazelle or a young stag.

Behold, there he is standing behind our wall,

Gazing through the windows,

Looking through the lattice.

Until the cool of the day,

When the shadows flee away,

Turn, my beloved, and be like a gazelle,

Or a young stag on the mountains of Bether.

Song of Solomon, 2:9, 2:17.

This genus was erected in 1758 by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), who named it for the Arabian word for gazelle, gazal. It includes 10 species, found in the northern half of Africa, Arabia, the Middle East, Central Asia, and the Indian Peninsula.

Formerly, the genus was larger, but 4 species have been transferred to the genus Eudorcas and 3 to Nanger.

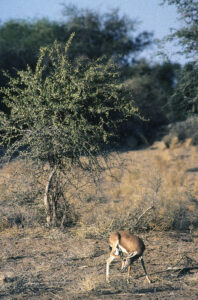

Gazella bennettii Chinkara, Indian gazelle

This small species is distributed from central and eastern Iran and southern Afghanistan eastwards through southern Pakistan to southern central India, living in deserts, arid hills, and dry scrub forests. In Pakistan, it has been found up to elevations of 1,500 m.

Six subspecies are recognized, some of which are regarded as full species by some authorities: The Deccan chinkara, subspecies bennettii, is distributed from the Gangetic Plain southwards to Andhra Pradesh, the Gujarat chinkara, ssp. christii, from southern Pakistan eastwards to Rajasthan and Gujarat, the Salt Range gazelle, ssp. salinarum, in eastern Pakistan and north-western India, the Kennion or Baluchistan gazelle, ssp. fuscifrons, in eastern Iran, southern Afghanistan, southern Pakistan, and Rajasthan, the Jebeer gazelle, ssp. shikari, in north-eastern Iran, and the Bushehr gazelle, ssp. karamii, in a small area near Bushehr, north-eastern Iran.

Populations of this gazelle have been severely reduced by hunting. The Iranian and Pakistani populations are scattered and fragmented, and it may be extinct in Afghanistan. The stronghold of the species is India, with an estimated 100,000 individuals, of which about 80,000 live in the Thar Desert in Rajasthan and Gujarat.

The specific name may refer to English physician and naturalist George Bennett (1804-1893), who travelled widely between 1828 and 1835. Later, he emigrated to Australia, where he held a number of posts, including president of the Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales.

Gujarat chinkaras, subspecies christii, in morning light, near Osiyan, Thar Desert, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Detail of the sculpture ‘The Descent of the Ganges’ (see blackbuck above), depicting chinkaras. – Mamallapuram, Tamil Nadu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hemitragus jemlahicus Himalayan tahr

This animal, the sole member of the genus, is widely distributed in the temperate zone of the Himalaya, found from Kashmir eastwards to Sikkim and extreme south-eastern Tibet, in summer encountered up to an elevation of 5,200 m, in winter sometimes descending to about 1,500 m. The population is declining due to hunting and habitat loss.

Elsewhere, this species has been introduced as a hunting object, including New Zealand, Argentina, and South Africa. In these countries numbers of tahrs have exploded, as they have no natural enemies here, and they have become a serious threat to the local environment through overgrazing.

In 1826, English artist, naturalist, antiquary, illustrator, soldier, and spy, Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Hamilton Smith (1776-1859) named this animal Capra jemlahica, meaning ‘the goat from Himalaya’. However, in 1841, the outstanding British naturalist and ethnologist Brian Houghton Hodgson (1801-1894) renamed it Hemitragus jemlahicus, derived from Ancient Greek hemi (‘half’) and tragos (‘goat’), thus ‘goat-like’. Apparently, he found that this animal was not really a goat. Today, however, genetic research has revealed that it is in fact a goat.

A stunning encounter with this animal is related on the page Travel episodes – India 2008: Mountain goats and frozen flowers.

Himalayan tahrs, grazing in the Khumbu area, eastern Nepal, where this species is common. The animals are not harmed by the local Buddhist Sherpas. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Naemorhedus Gorals

A genus with 4 species of small, stocky, goat-like animals, distributed in Central Asia. Goral is the Hindi name of these animals, probably of Sanskrit origin. The generic name is explained below.

Naemorhedus goral Himalayan goral

This species is usually 1-1.3 m long, weighing 35-42 kg, with short, curved horns. It is found along the Himalaya, from Pakistan eastwards to Arunachal Pradesh, mostly living on the lower slopes, at elevations between 1,000 and 3,000 m. The population is declining significantly due to habitat loss and hunting.

In 1825, English soldier and naturalist, Major-General Thomas Hardwicke (1755-1835) named this animal Antilope goral. Apparently, he found that it resembled an antelope, presumably due to its small size. Only two years later, Hamilton Smith (see tahr above) renamed it Naemorhedus, derived from the Latin nemus (‘forest’) and haedus (‘a young goat’). Later research has shown that it is neither a true antelope or a true goat, but a member of the so-called goat-antelopes, which have traits from both groups. Other goat-antelopes are the Asian serow (Capricornis), the European chamois (Rupicapra), and the American mountain goat (Oreamnos).

Incidentally, Smith made two spelling mistakes in the name Naemorhedus. It ought to be Nemorhaedus. However, according to the rules of nomenclature, we must stick to the former spelling.

Himalayan goral in its typical habitat: grassy slopes, interspersed with rocks and taller vegetation. – Amjilassa, Lower Ghunsa Valley, eastern Nepal (upper two), and near Shyabrubesi, Langtang National Park, central Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Himalayan goral, resting on a rock ledge, near Sherpagaon, Lower Langtang Valley, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This picture from Delhi Zoo shows the stockiness of the goral. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nilgiritragus hylocrius Nilgiri tahr

“Still, so tenuous is the existence of this species that one-fourth to one-third of all the Nilgiri tahr in existence were within my view from Anaimudi Peak.”

This quote is from the book Stones of Silence: Journeys in the Himalaya (1980), by German-American biologist and environmentalist George B. Schaller (born 1933). In the 1970s, he estimated that the total population of the Nilgiri tahr might be as low as 1,500 individuals. Since then, conservation measures have caused its numbers to increase to about 3,100. This species is restricted to high altitudes in the southern Western Ghats in Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

Formerly, it was placed in the genus Hemitragus, together with the Himalayan tahr (above) and the Arabian tahr (H. jayakari, today called Arabitragus jayakari). However, genetic research has shown that it is more closely related to sheep of the genus Ovis than to the other tahrs, and, consequently, it was moved to a separate genus.

The last part of the generic name is derived from Ancient Greek tragos (‘goat’), thus ‘the goat from the Nilgiri Hills’. The specific name is likewise from Ancient Greek, from hyle (‘forest’) and Krios, one of the Titans, son of Uranus and Gaia.

Eravikulam National Park, Kerala, where the pictures below were taken, is a stronghold of the Nilgiri tahr, housing an estimated 800-900 individuals, app. one-fourth of the total population.

Nilgiri tahrs. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nilgiri tahrs, scratching and grooming. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nilgiri tahr female with a suckling kid. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nilgiri tahr ‘kindergarten’. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pseudo-mating, a male mounts another male. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In the late 1990s, tourists began feeding the tahr in Eravikulam, and the animals lost their fear of people. This practice has since been banned. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pseudois nayaur Bharal, Himalayan blue sheep, Chinese blue sheep

Today, this species is considered the only member of the genus. For many years, it was assumed that an animal living in eastern Tibet and the Sichuan Province was a distinct species, called dwarf blue sheep or dwarf bharal (P. schaeferi). However, genetic research has shown that it is a mere dwarf form of the common bharal.

Today, this species is considered the only member of the genus. For many years, it was assumed that an animal living in eastern Tibet and the Sichuan Province was a distinct species, called dwarf blue sheep or dwarf bharal (P. schaeferi). However, genetic research has shown that it is a mere dwarf form of the common bharal.

The adult ram is a splendid animal, weighing up to 75 kilos, with thick, sweeping horns that may grow to a length of 80 cm. The coat is grey with a bluish sheen (hence its English name), with black markings on chest, flanks, and legs. Ewes and young males are more uniformly grey. The horns of females are small, growing to 20 cm long.

This species is widely distributed in Central Asia, from Ladakh, the northern Himalaya, and the Yunnan Province northwards across Tibet to Gansu, Ningxia, and Inner Mongolia. The Helan Mountains of Ningxia have the highest concentration of bharal in the world, with a population of about 30,000. It is also quite common in parts of the Himalaya, including Ladakh, Dolpo, and the border area between Nepal and Sikkim.

Bharal is the Hindi name of this animal, whereas the Nepali name naur has given rise to the specific name. The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek pseudes (‘false’) and ois (‘sheep’), alluding to the fact that the animal is sheep-like, but also has traits from goats.

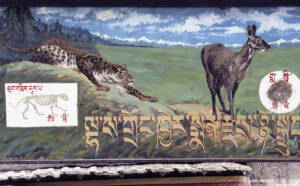

The bharal was the main focus of an expedition to the Dolpo area of Nepal in 1973, led by German-American zoologist George Schaller (born 1933). He was accompanied by the famous American writer and environmentalist Peter Matthiessen (1927-2014). Their personal experiences are well documented in Schaller’s book Stones of Silence: Journeys in the Himalaya (1980), and Matthiessen’s The Snow Leopard (1978).

Bharals, illuminated by morning sun, Trisul Nala, Nanda Devi National Park, Kumaon, Uttarakhand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bharals, grazing in a semi-desert near Niki La Pass, Ladakh. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bharals, Ramtang, Upper Ghunsa Valley, eastern Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

My guide Karma Tsering, showing the sweeping horns of a bharal, Ulley, Ladakh. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tetracerus quadricornis Four-horned antelope, chowsingha

This tiny antelope, the only member of the genus, stands only about 60 cm at the shoulder and weighs about 20 kg. It is the only wild bovid with four horns, of which the anterior pair, in the centre of the skull, is much smaller than the posterior pair.

These horns have given rise all names of this animal. The generic name is from the Greek tetra (‘four’) and keras (‘horn’), whereas the specific name is from the Latin quattuor (‘four’) and cornu (‘horn’). The Hindi name chowsingha is derived from chaar (‘four’) and siing (‘horn’).

Three subspecies have been described, quadricornis, which is distributed in most of the Indian Peninsula, subquadricornutus, which is found in southern India, and iodes, which is restricted to southern Nepal.

Female four-horned antelope, drinking from a waterhole in Sariska National Park, Rajasthan. Note the many bees around the animal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female at a waterhole, Sariska National Park. Peafowl (Pavo cristatus) and a crested bunting (Melophus lathami) are also present. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female at a waterhole, Sariska National Park. The birds are a white-browed fantail (Rhipidura aureola) and a crested bunting (Melophus lathami). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female with a kid at a waterhole in Sariska National Park. A northern plains langur (Semnopithecus entellus, see below) is seen to the left. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Canidae Dog family

This family, comprising about 35 species, includes domestic dogs, wolves, jackals, hunting dogs, foxes, and many other dog-like animals. About 50 million years ago, a group of carnivores split into two groups, the cat-like Feliformia and the dog-like Caniformia.

The latter evolved into a large number of families, of which the Canidae, about 12 mio. years ago, split into three groups:

Canini includes wolf-like dogs, and South American dogs and foxes.

Vulpini includes typical foxes, bat-eared fox (Otocyon megalotis), and raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides)

Two foxes of the genus Urocyon seem to have split out at a very early stage (Lindblad-Toh et al. 2005). Modern taxonomists do not include these two species in Canini or Vulpini.

Many species are presented on the page Animals – Mammals: Dog family.

Canis Wolf-like dogs

In later years, following a number of genetic studies, this genus has been the cause of much confusion and has been revised several times. As of 2022, the genus contains between 5 and 11 species. All authorities now recognize 5 species: grey wolf (C. lupus), coyote (C. latrans), African golden wolf (C. lupaster), Ethiopian wolf (C. simensis), and golden jackal (below). Others also regard one or more of the following as separate species: domestic dog (C. familiaris), dingo (C. dingo), red wolf (C. rufus), eastern wolf (C. lycaon), Indian wolf (C. pallipes), and Himalayan wolf (C. himalayensis).

Recently, two species of jackals, the black-backed (formerly C. mesomelas) and the side-striped (formerly C. adustus), have been moved to a separate genus, Lupulella.

Canis aureus Golden jackal

A highly adaptable and successful animal, living in a large variety of habitats. As it often takes domestic fowl and lambs, it is much persecuted, but is nevertheless still expanding its range. Today, 7 subspecies are distributed from Myanmar and Thailand westwards through India, Sri Lanka, the Middle East, and the Arabian Peninsula to the Balkans, Austria, and parts of Germany. Since 2015, several animals have been reported as far north as Denmark.

In north-western India, the ranges of the subspecies aureus and indica overlap.

Golden jackal in morning light, Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Golden jackal, drinking from a waterhole, Sariska National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On an extremely hot April day, this pair of golden jackals enjoy a bath in a waterhole, Sariska National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cercopithecidae Old World monkeys

This large family, comprising 24 genera and about 140 species, is widely distributed in Africa and Asia. Members include baboons, macaques, colobus monkeys, langurs, and many others. A large number are described on the page Animals – Mammals: Monkeys and apes.

Macaca Macaques

The number of species in this genus has been growing steadily in later years to 23, as two new species have recently been described.

The generic name stems from the word makaku, plural of kaku, a West African Bantu name for a species of mangabey. In Portuguese, makaku became macaco, and in French macaque, the latter adopted by the British. In 1798, French taxonomist Bernard Germain de Lacépède (1756-1825) applied this word of African origin, in the form Macaca, to an almost exclusively Asian group of monkeys, presumably because he was familiar with the Barbary macaque (Macaca sylvanus) – the only species of the group outside Asia, living in north-western Africa and on the Rock of Gibraltar, southern Spain. (Source: itre.cis.upenn.edu/~myl/languagelog/archives/003458.html)

Macaca assamensis Assamese macaque

This monkey is quite similar to the well-known rhesus macaque (below), but has a longer tail, and it lacks the orange hindquarters of that species. It is distributed from western Nepal eastwards to south-western China, and also has populations in Indochina and Bangladesh.

It generally lives in forests at altitudes between 200 and 2,000 m, but may be observed down to sea level in Bangladesh, and it occasionally strays to high mountains, sometimes as high as 4,000 m. It is declining in many places due to hunting and habitat fragmentation.

Members of a troop of about 50 Assamese macaques, observed near Pairo, Lower Langtang Valley, central Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Macaca mulatta Rhesus monkey

Here we go in a flung festoon,

Half-way up to the jealous moon!

Don’t you envy our pranceful bands?

Don’t you wish you had extra hands?

Wouldn’t you like if your tails were – so –

Curved in the shape of a Cupid’s bow?

Now you’re angry, but – never mind,

Brother, thy tail hangs down behind!

Here we sit in a branchy row,

Thinking of beautiful things we know;

Dreaming of deeds that we mean to do,

All complete, in a minute or two –

Something noble and grand and good,

Won by merely wishing we could.

Now we’re going to – never mind,

Brother, thy tail hangs down behind!

All the talk we ever have heard

Uttered by bat or beast or bird –

Hide or fin or scale or feather –

Jabber it quickly and all together!

Excellent! Wonderful! Once again!

Now we are talking just like men.

Let’s pretend we are – never mind,

Brother, thy tail hangs down behind!

This is the way of the Monkey-kind.

Then join our leaping lines

that scumfish through the pines,

That rocket by where, light and high, the wild-grape swings,

By the rubbish in our wake,

and the noble noise we make,

Be sure, be sure, we’re going to do some splendid things!

Road song by the Bandar-log, from The Jungle Book (1894), by English writer Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936). In Hindi, bandar-log means ‘monkey-people’.

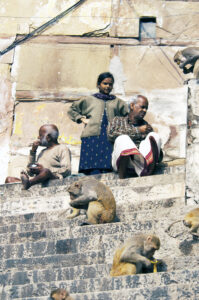

The rhesus monkey is the well-known brown monkey of northern India, in Hindi called bandar. It is found almost everywhere in the country north of the rivers Tapti in Gujarat and Godavari in Maharashtra. The total distribution area stretches from Afghanistan eastwards through Pakistan, India, Nepal, Bangladesh, and the northern part of Myanmar, Thailand, and Laos to Vietnam, and thence northwards to central China.

Its fur is mainly brown, with yellowish-orange hind parts, and the tail is rather short, 20-30 cm. This monkey lives in very diverse habitats, from semi-desert via various forest types to temple groves and cities, from the lowland up to altitudes around 2,500 m.

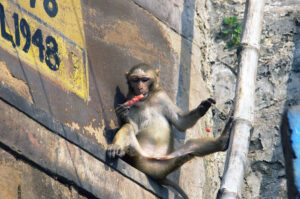

Following a strong decline due to felling of forest, combined with export of many animals for medical research, the rhesus monkey is now expanding in India, with an estimated population of 500,000 individuals, or more. This expansion is mainly due to the fact that it has adapted to a life in cities.

The size of a territory of a typical troop of rhesus monkeys has been measured at up to 16 km2 in montane forest, and 1-3 km2 in other types of forest, whereas in Kolkata, a troop of 62 individuals was studied, thriving successfully in an area of less than 4 hectares, in the centre of this metropolis.

In some areas, especially in Laos and Vietnam, the species is hunted for food, and habitat destruction has also affected populations locally in Indochina.

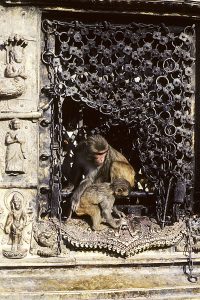

In the great Hindu epic Ramayana, the monkey army, led by Hanuman, plays a significant role, and for this reason monkeys are regarded as sacred animals among devout Hindus. Troops of rhesus monkeys, bonnet macaques (below), and northern plains langurs (below) often live around temples, where part of their diet consists of rice, sweets, or other edibles, brought as offerings to the gods.

Examples of such temples are Pashupatinath, a Hindu temple on the shores of the Bagmati River, Kathmandu, the Manakamana Kali Temple in central Nepal, and the great Buddhist stupa Swayambhunath in Kathmandu, which also contains Hindu shrines.

The role of the monkey army in Ramayana is described on the page Animals – Mammals: Monkeys and apes.

In the West, the rhesus monkey has become well-known due to its usage in medical research, which detected the rhesus factor, an inherited antigen in the blood of humans.

The specific name is of unknown origin. The common name may refer to a person in Greek mythology, King Rhesus of Thrace, who sided with the Trojans during the Trojan War, related in the Iliad.

The fur on the rear part of the rhesus monkey is yellowish-orange. This one has found a garland of marigold flowers, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The behind of rhesus monkeys is reddish with two bare patches of skin that the animal sits on. – Swayambhunath, Kathmandu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rhesus monkey, Varanasi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rhesus monkeys, resting on a chorten (a Tibetan Buddhist shrine, similar to a stupa), Swayambhunath. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Clinging to a clothes-line, this one is looking through a window, Varanasi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is walking along a narrow wall, surrounding the Hawa Mahal Palace, Jaipur, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This rhesus monkey is enjoying the morning sun, sprawled on a tree branch, where it spent the previous night, Uttarkashi, Garhwal, Uttarakhand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rhesus monkeys are true acrobats, sometimes walking on wires from one building to the next, or even hanging upside down. – Haridwar, Uttarakhand (top), and Swayambhunath. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female rhesus monkeys are affectionate mothers. These were photographed at the Manakamana Kali Temple (top), and at Swayambhunath. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rhesus monkeys spend a considerable time grooming. – Swayambhunath (top), and Pashupatinath, Kathmandu. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Copulating rhesus monkeys, Swayambhunath. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Females and young on a wall near the Ganges River, Varanasi. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This young rhesus monkey jumps from one wall to another, Varanasi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rhesus monkeys, eating offerings of rice, Manakamana Kali Temple, central Nepal (top), and Swayambhunath. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rhesus monkeys, gnawing banana peels, Varanasi. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These rhesus monkeys are eating biscuits, presented by a tourist, Manakamana Kali Temple. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This young monkey is eating a piece of water melon, Varanasi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

One day, when I had visited the Swayambhunath Stupa, I was descending the staircase, when I heard a strange sound behind me. Turning around, I saw an empty Tuborg beer can come tumbling down the stairs, pass me, and come to a stop just in front of a rhesus monkey. The monkey grabbed the can, sniffed it, and then quickly dropped it, baring its teeth as if to say, “This stuff is not for me!”

(Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A street entertainer with performing rhesus monkeys, Delhi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Macaca radiata Bonnet macaque

This macaque is restricted to the southern half of India, replacing the rhesus monkey south of the Tapti and Godavari Rivers. It is a little smaller than the rhesus monkey, its fur is greyish-brown, paler on the belly. It has an extremely long tail, longer than the body. On its crown is a cowlick, resembling a bonnet. The specific name also refers to the cowlick.

It is very common, locally abundant, living in all forest types, scrubland, plantations, agricultural lands, and urban areas. It is usually found below 2,000 m altitude, occasionally up to 2,600 m. As it often feeds in agricultural areas, conflicts with humans is an increasing problem. It is locally hunted, and many are caught for research, as well as for street performing.

Whereas the temple monkeys in northern India are mainly rhesus monkeys, this role is taken over by bonnet macaques in southern Indian temples.

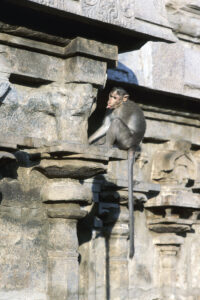

The bonnet macaque has a very long tail, longer than the body. This one, resting on a cornice in the Sri Minakshi Temple, Madurai, Tamil Nadu, is licking on a discarded drinking straw. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male bonnet macaque, resting in a growth of bamboo, Periyar National Park, Kerala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This bonnet macaque in Honnevara Forest, Karnataka, is trying to decide, whether I am dangerous or not. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female bonnet macaques are loving mothers. This one with a tiny young was observed at Azhiyar Ghat, Tamil Nadu. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one at Singhur Ghat, Nilgiri Mountains, Tamil Nadu, is feeding on acacia seeds. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sitting on our car, this one is gnawing on a banana peel, afterwards looking at its own reflection in the rear window. – Azhiyar Ghat. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This bonnet macaque is washing food in the Theppakadu River, Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, Tamil Nadu, before eating it. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A large troop of bonnet macaques live around the famous Hindu cave temples in the city of Badami, Karnataka. In this picture, several females and a young huddle together to keep warm in the morning cold. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Three females, one with a tiny young, Badami. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This female is grooming another monkey, presumably its young, Badami. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young bonnet macaque, enjoying the evening sun, Badami. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Like most other macaques, bonnet macaques love bathing, as these young ones in the Theppakadu River, Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, Tamil Nadu. After the bath, their ‘bonnet’ looks rather punky. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This bonnet macaque is crossing a heavily trafficked road in Badami by balancing on an electric wire, using its long tail as counter-balance. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

At temples, food is always plentiful, and as the monkeys don’t move much around, they often become obese, like this one, observed in the Sri Minakshi Temple, Madurai, Tamil Nadu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Macaques, which live near humans, often become scavengers, like this bonnet macaque in Periyar National Park, Kerala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This street entertainer in the city of Tirumalai, Andhra Pradesh, has caught two young bonnet macaques, which he is going to train to perform. They seem to be arguing about something. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This relief in a Jain temple atop the rock Vindyagiri, Sravanabelagola, Karnataka, depicts a bonnet macaque, embracing a jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Macaca silenus Lion-tailed macaque

This macaque is unique, as both male and female have a huge greyish mane around the head, which has given rise to its German name, Bartaffe (‘bearded monkey’). Apart from the mane, the fur is jet-black. The English name stems from another characteristic of this animal: the tuft at the end of the tail.

The lion-tailed macaque is endemic to rainforests of the southern part of the Western Ghats, in Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu. Although it is distributed in a huge area, the factual area of occupancy is small, as its habitat has been severely fragmented due to establishment of agricultural areas and plantations of tea, coffee, cardamom, and eucalyptus.

The total population of this animal is estimated at less than 4,000 individuals, made up of 47 isolated sub-populations. In one location, the Kodagu District, Karnataka, the species was formerly highly threatened by hunting for food. In later years, the population seems to have become stabilized due to better protection measures.

The specific name is a Latinized version of Ancient Greek Seilenos, in Greek mythology tutor of the wine god Dionysus.

The pictures below are all from the Puthutottam Forest, Tamil Nadu, where a troop of lion-tailed macaques have become accustomed to people, as they are often being fed by tourists.

Lion-tailed macaques on the road through Puthutottam Forest, Tamil Nadu. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This male is baring his huge canines, but he is probably just yawning, as this species is not at all aggressive towards people. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female with a young. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This lion-tailed macaque is lying on the road, eating tiny pebbles, which make loud crunching noises between its teeth! (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lion-tailed macaque in its true habitat: rainforest. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Macaca sinica Toque macaque

This reddish-brown monkey resembles the bonnet macaque, but the cowlick is further forward on its crown. It is restricted to Sri Lanka, where 3 subspecies are recognized, sinica in the dry zone of the eastern and northern parts of the island, aurifrons in the south-western lowland rainforest zone, and opisthomelas in the central highland wet zone.

It lives in a variety of forest types, from sea level up to about 2,100 m. The distribution areas of all three subspecies are very fragmented, and opisthomelas is restricted to an area of less than 500 km2, with only a fifth of this area actually occupied by the animals. The chief threat to this species is habitat loss due to establishment of plantations and agricultural lands. Many are shot, as they are doing considerable damage to crops.

The toque macaque is still widely distributed, but the population may have declined by more than 50% since 1975.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘from China’. When Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) named the species in 1771, he must have been misinformed about the origin of it. The common name is a kind of hat without brim.

The dry-zone race of the toque macaque, sinica, is found in the eastern and northern parts of Sri Lanka. This one was photographed at Polonnaruwa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young toque macaque, sitting between stilt roots of a banyan fig (Ficus benghalensis), Sigiriya, eastern Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This young toque macaque at Polonnaruwa is drinking by dipping its hand into a puddle inside a hollow tree trunk, whereupon it licks its hand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subspecies aurifrons is distributed in the south-western lowland rainforest zone. This one was observed in Sinharaja Forest Reserve. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Semnopithecus Typical langurs

This genus of leaf-eating monkeys contains about 8 species, all restricted to the Indian Subcontinent. In the past, all grey langurs living here were regarded as belonging to a single species, S. entellus, divided into six subspecies. However, recent morphological studies, combined with DNA-analyses, suggest that the grey langurs should be regarded as 6 full species: northern plains langur (S. entellus), terai langur (S. hector), pale-armed langur (S. schistaceus), Kashmir langur (S. ajax), black-footed langur (S. hypoleucos), and tufted langur (S. priam). A seventh species, dussumieri, has been declared conspecific with northern plains langur.

Today, most authorities consider all langurs on the Indian Subcontinent as belonging to the this genus. Formerly, two species, the Nilgiri langur (S. johnii) of south-western India, and the purple-faced langur (S. vetulus) of Sri Lanka, were regarded as members of the genus Trachypithecus (below),which is today considered to be distributed only in north-eastern India, Bhutan, and Southeast Asia.

The generic name is from the Greek semnos (‘sacred’) and pithekos (‘monkey’), alluding to the sanctity of monkeys to Hindus. The role of the langur in the great Hindu epic Ramayana is described on the page Animals – Mammals: Monkeys and apes.

Semnopithecus entellus Northern plains langur

This speciesis widespread in northern, central, and south-central India, from Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal southwards to Telangana and northern Karnataka and Kerala, with a small population in western Bangladesh, which probably originated from a single pair, introduced by Hindu pilgrims on the bank of the Jalangi River.

It is quite common, living in a variety of habitats, including forests, scrubland, temple groves, gardens, and towns, up to an altitude of c. 1,700 m. It is locally threatened by habitat loss due to intensified agriculture and fires, and by hunting for food by newly settled people in Andhra Pradesh and Orissa.

Previously, western and southern populations of this species were regarded as a separate species, the southern plains langur (S. dussumieri), but recent genetic research has declared this name invalid.

The specific name refers to an aged Trojan, mentioned in the poem The Aeneid, by Roman poet Publius Vergilius Maro (70-19 B.C.), also known as Virgil. The Aeneid relates the legendary story of Aeneas, a Trojan who fled after the fall of Troy to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Romans.

Northern plains langurs in morning sun, Sariska National Park, Rajasthan. This species usually carries its tail arched over its back. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Northern plains langurs, drinking from a waterhole, Sariska National Park. Note the many bees in the bottom picture. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Troop of northern plains langurs, resting on a rock outside the sacred Udayagiri Caves, near Bhubaneswar, Odisha. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This female outside the Udayagiri Caves has a tiny young. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Resting male, Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This male is baring his teeth as a sign of aggression, Sariska National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pseudo-mating young, Sariska National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In many places, the northern plains langurs have adapted to a life in cities, where they often become a menace, stealing fruit or other edibles that are not guarded. Their status as sacred animals ensure that they are not harmed, despite their impudence. They are also common around temples, where they feed on rice and other edibles, brought by devout Hindus as offerings to the gods.

These northern plains langurs are sitting on a roof top in the town of Pushkar, Rajasthan, from where they, like a bunch of street urchins, survey the surroundings for fruit or other edibles to steal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Northern plains langurs, resting in a pavilion near the sacred lake in Pushkar. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

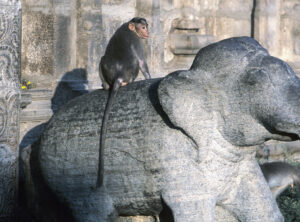

This one is resting on a sculpture, depicting the bull Nandi, mount of the great Hindu god Shiva, Chittorgarh Fort, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A Hindu legend relates that a young man named Narad Muni went to participate in a Swayamwara, during which young girls can choose a husband. This young man was very proud of himself and was convinced that he was the most handsome among the men. However, as the day came to an end, he went away heartbroken, because none of the young girls had chosen him. On his way home, he got thirsty, so he went to a waterhole to quench his thirst. His reflection in the water told him that he now had a monkey’s head.

”His reflection in the water told him that he now had a monkey’s head.” – Sariska National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Semnopithecus hector Terai langur

This species is found in the Himalayan foothills, the terai, encountered up to an altitude of about 1,600 m, from Uttarakhand eastwards to south-western Bhutan. It mainly lives in forests, occasionally feeding in orchards and fields with crops. Its fur is thicker than that of the northern plains langur (above), but not as rich as that of the pale-armed langur (below).

The total number of terai langurs is probably only about 10,000 mature individuals, and the population is slowly declining, mainly due to habitat loss.

The specific name refers to a person in Greek mythology, Prince Hector of Troy, who was one of the foremost fighters among the Trojans during the Trojan War, related in the Iliad.

During an excursion with my Indian friend Ajai Saxena to Rishikesh, Uttarakhand, we had company of a couple of terai langurs, which took their seat on the roof of our car. Presumably, many car drivers feed these monkeys, but as we oppose the habit of feeding wild animals, we didn’t give them anything, and shortly after they disappeared, jumping into the trees. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Semnopithecus hypoleucos Black-footed langur

This monkey has jet-black hands and feet, contrasting sharply with its grey arms and legs. It occurs in the Western Ghats, from Goa southwards through Karnataka to Kerala. In some areas, it is seriously threatened by hunting, and it has already been extirpated from parts of the Brahmagiri Hills in Kodagu District, Karnataka.

Some authorities believe that the black-footed langur is a natural hybrid between the northern plains langur (above) and the Nilgiri langur (below), and others regard it as a subspecies of the former.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek hypo (‘beneath’) and leukos (‘white’), alluding to the whitish belly of this species.

The black-footed langur has jet-black hands and feet, contrasting sharply with its grey arms and legs. – Dandeli Wildlife Sanctuary, Karnataka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Black-footed langur, eating leaves, Dandeli Wildlife Sanctuary. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one in Anshi National Park, Karnataka, is busy scratching itself. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is climbing up a dead bamboo stem, from which it jumps onto another one, Anshi National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Black-footed langur, eating flower buds of a silk-cotton tree (Bombax ceiba), Honnavar Forest, Karnataka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Semnopithecus johnii Nilgiri langur

This species is jet-black, with pale-brown fur on the crown and on a ruff around its face. It is restricted to the Western Ghats in Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu, where it lives in forests at elevations between 300 and 2,000 m.

Formerly, it was threatened by habitat loss due to mining, dams, and human settlement, and by hunting, but the latter has decreased in recent years due to better protection, and after the introduction of the Indian Wildlife Protection Act in 1972, the population has increased. Since the 1990s, it has been relatively stable, counting around 20,000 individuals.

Previously, this species was placed in the genus Trachypithecus (below).

The specific name honours German missionary and naturalist Christoph Samuel John (1747-1813), who worked for the Danish-Halle Mission in the Danish settlement of Tranquebar, Tamil Nadu, today known as Tarangambadi.

Nilgiri langurs, eating leaf buds, Periyar National Park, Kerala. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nilgiri langur, Eravikulam National Park, Kerala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Semnopithecus priam Tufted langur

Two subspecies of this monkey are recognized, priam, which occurs in several disjunct populations, from the southern shores of the Krishna River, Andhra Pradesh, southwards to the city of Madurai, Tamil Nadu, whereas subspecies thersites is found in parts of the Western Ghats, and in the dry zone of Sri Lanka. The affinity of some South Indian populations is not known, as they have been very poorly studied. Genetic research indicates that there are consistent differences between the two taxa, and maybe they will be split into two separate species in the future.

The tufted langur lives in forests, temple groves, gardens, and cultivated areas, in India up to altitudes around 1,200 m, in Sri Lanka up to about 500 m.

The specific name refers to Priam, in Greek mythology the legendary last king of Troy during the Trojan War.

Tufted langurs, subspecies priam, Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, Tamil Nadu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tufted langurs, seen as silhoettes against the light, Mudumalai Tiger Reserve. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tufted langur, Masinagudi, Mudumalai Tiger Reserve. Spotted deer (Axis axis) are seen in the background. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tufted langur, Masinagudi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This male is baring his teeth as a sign of aggression, Masinagudi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tufted langur, running full speed along a road, Mudumalai Tiger Reserve. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tufted langur, ssp. thersites, Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tufted langurs, Anuradhapura , Sri Lanka. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This is probably a hybrid between tufted langur and Nilgiri langur (above), Annamalai National Park, Tamil Nadu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Semnopithecus schistaceus Pale-armed langur, Nepal langur

This species is easily identified by its luxurious, pale grey fur and the large white ruff around its jet-black face. It has a wide distribution at mid-elevations in the Himalaya, mostly between 1,500 and 3,500 m, but occasionally up to 4,000 m, from Pakistan through India and Nepal to Bhutan and extreme south-eastern Tibet.

It mainly lives in lush monsoon forests, occasionally found in scrubland and agricultural areas. It is quite common, and the population is fairly stable. Threats include habitat loss through logging, fire, and human encroachment, and it is hunted in Tibet for usage in traditional medicine.

The specific name is derived from Latin, meaning ‘slate-coloured’ – very pale slate, one must say!

Part of a large troop of pale-armed langurs, resting and playing in a meadow, Ghora Tabela, Upper Langtang Valley, central Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pale-armed langurs, resting on a stone wall, Kuldi Ghar, Modi Khola Valley, Annapurna, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male pale-armed langur, resting in a tree, Tadapani, Annapurna, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pale-armed langurs, Dodi Tal Lake, Upper Asi Ganga Valley, Garhwal, Uttarakhand. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is feeding on buds and flowers of Viburnum grandiflorum, Dodi Tal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Troop of pale-armed langurs, eating soil to obtain minerals, Banthanti, Annapurna, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Semnopithecus vetulus Purple-faced langur

Four subspecies of this langur are recognized, all restricted to Sri Lanka.

The nominate vetulus lives in an area of less than 5,000 km2 of rainforest in south-western Sri Lanka, up to an altitude of around 1,000 m. Where its natural habitat has been destroyed, it may live in gardens and plantations, but these habitats offer no long-term survival prospects for it. Subspecies nestor lives in a similar habitat, further north than vetulus, whereas philbricki is found in moister forests of the dry zone. Subspecies monticola is restricted to the montane forests of central Sri Lanka, at elevations between 1,000 and 2,200 m.

All four subspecies are endangered, as they are believed to have undergone a decline of more than 50% in the last 40 years due to habitat loss and hunting.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘old’. It probably refers to the large whitish beard of this otherwise dark monkey.

Like the Nilgiri langur (above), the purple-faced langur was formerly placed in the genus Trachypithecus.

Portrait of a captive lowland purple-faced langur, of subspecies vetulus or nestor, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The dry-zone subspecies of the purple-faced langur, philbricki, is found in forests of moister areas of the dry zone of Sri Lanka. These pictures are from Polonnaruwa. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Trachypithecus Lutungs

This genus, encompassing 15 species, is distributed from Bhutan and north-eastern India eastwards to the southernmost parts of China, and thence southwards through Southeast Asia to the Indonesian islands Java, Bali, and Lombok.

This genus, counting 15 species, is distributed from Bhutan and north-eastern India eastwards to the southernmost parts of China, and thence southwards through Indochina to Java, Bali, and Lombok.

The generic name is derived from the Greek trach (‘rough’) and pithekos (‘monkey’), referring to the dense fur of some species in the genus.

Trachypithecus geei Golden langur

This species occurs only in Bhutan and adjacent parts of Assam, between the rivers Manas in the east and Sankosh in the west. It lives in forests along the foothills of the Himalaya up to elevations around 3,000 m.

Its total known range is less than 30,000 km2, and much of it is not suitable habitat. The estimated population is less than 1,200 individuals in India and around 4,000 in Bhutan. It has declined by more than 30% in the last 30 years and is expected to decline further due to habitat loss. The population in India is highly fragmented, with the southern population completely separated from northern populations due to the effects of human activities.

The population in Manas National Park, Assam, is threatened by hybridization with a close relative, the capped langur (T. pileatus). Formerly, these two species were separated by rivers, but a number of constructed bridges has now made it easy for them to cross these rivers.

The golden langur was described as late as 1956, but was known much earlier by naturalists, the earliest record being by R.B. Pemberton in a paper from 1838, Report on Bootan Indian Studies Past and Present. However, his work was lost and not rediscovered until the 1970s, and the golden langur was not mentioned again until 1907, when E.O. Shebbeare reported seeing a ’cream-coloured langur’ in the vicinity of Jamduar.

In 1919, a publication stated that a pale yellow-coloured langur was common in a district near Goalpara in Assam, and in 1947, C. G. Baron wrote: ”I saw some white monkeys (…) and, as far as I know, they are an undescribed species. Their entire body and tail are of the same colour – pale silver-golden, not unlike a blonde.”

A number of other sightings roused the interest of celebrated naturalist Edward Pritchard Gee (1904-1968), who observed and photographed three troops of golden langurs in 1953. He reported his results to the Zoological Survey of India, and in 1955 six specimens were collected. The species was described by Dr. H. Khajuria, who named it Presbystis gee, in honour of Mr. Gee.

Golden langurs, Manas National Park, Assam. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cervidae Deer

These animals differ from other ruminants by possessing antlers, which are shed every year. The family contains 20 genera with about 90 species. Many species are presented on the page Animals – Mammals: Deer.

Deer live in almost all types of habitats, ranging from tundra to tropical rainforest. They are widely distributed, with native species present in all continents, except Antarctica and Australia. In Africa, however, only a single species is present in the Atlas Mountains. The largest concentration of species is found in Asia.

A larger deer male is called a stag, a female a hind, and a young a kid or a calf. A smaller deer male is called a buck, a female a doe, a young a fawn.

Axis

Previously, the hog deer (Hyelaphus porcinus, below) and three other small deer were placed in this genus. However, genetic studies have revealed that they differ sufficiently from the spotted deer (below) to constitute a separate genus, leaving the latter as the only member of the genus.

Axis axis Spotted deer, chital

This beautiful deer is native to the Indian Subcontinent, including Sri Lanka, but is found nowhere else. It is fairly common in most of the distribution area, though declining in places due to habitat destruction. It has been introduced elsewhere, including Australia, the United States, and several South American countries.

A medium-sized deer, males may weigh up to 100 kg, whereas the females are much lighter.

The generic and specific names are Latin, referring to an Indian animal, mentioned by Roman philosopher and naturalist Pliny the Elder (c. 23-79 A.D.). The Hindi name chital is derived from Sanskrit citrala (‘spotted’).

Spotted deer stag, drinking from a waterhole in Sariska National Park, Rajasthan. A rufous treepie (Dendrocitta vagabunda) is sitting on its back. To the left a peacock (Pavo cristatus). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Resting spotted deer stag, with antlers in velvet, Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This hind with a kid is raising her tail as an alarm signal, Sariska National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

When approaching these spotted deer in Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, Tamil Nadu, I stepped on a dead branch. The sound immediately made them raise their heads and stare in my direction. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spotted deer in grassland, Corbett National Park, Uttarakhand. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

We found this abandoned kid in the grassland of Corbett National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On a baking hot summer day, spotted deer quench their thirst in a waterhole, Sariska National Park. The palms in the background are Indian date palms (Phoenix sylvestris). A peahen (Pavo cristatus) is seen in the lower picture. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This stag was killed by a tiger or a leopard, but was left due to heavy rain, Corbett National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cervus

Genetic research indicates that this genus evolved in Central Asia, where an ancient species, now named Cervus hanglu, still exists, with 3 subspecies, the Kashmir stag (below), the Bactrian deer, ssp. bactrianus, which is widespread in Central Asia, and the Yarkand deer, ssp. yarkandensis, which is restricted to Xinjiang. About 7 million years ago, the climate became cooler, causing this ancestral deer to migrate north, east, and west.

Today, the western Eurasian group, called red deer (C. elaphus), has several subspecies in western Europe, the Balkans, the Middle East, and North Africa. However, the taxonomy of this group remains unsettled, and some subspecies may merit specific status, including C. (e.) corsicanus, which lives on Corsica and Sardinia. It may be conspecific with the Barbary stag (C. (e.) barbarus) of north-western Africa.

The eastern Eurasian group includes the wapiti (C. canadensis), which is distributed in north-eastern Asia and North America, Thorold’s or white-lipped deer (C. albirostris), which occurs in eastern Tibet, Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan, and north-western Yunnan, and the sika deer (C. nippon), which is found in Japan and Taiwan, at scattered locations in eastern China, and in Ussuriland, south-eastern Siberia.

Some authorities place several South Asian deer in the genus Cervus, others in the genus Rusa, including the sambar deer (below) and the rusa deer (C. timorensis or R. timorensis).

The generic name is the classical Latin term for deer.

Cervus hanglu ssp. hanglu Kashmir stag

Traditionally, this deer was regarded as a subspecies of C. elaphus. However, recent genetic studies have concluded that it belongs to an ancient lineage (see genus above).

It is restricted to a few locations in Kashmir and northern Himachal Pradesh. Habitat destruction, competition from grazing livestock, and poaching brought it to the brink of extinction, with only about 150 individuals surviving around 1970. Conservation measures has had the effect that the population is now around 300, but this number is still dangerously low.

The specific name is a corruption of hangul, the local Kashmir name of this deer.

This picture is from the interesting Hindu temple Hadimba in Manali, Himachal Pradesh, which is adorned with various items, including antlers of Kashmir stag, ringed horns of Siberian ibex (Capa sibirica, see above), and smooth horns of bharal (Pseudois nayaur, see above). The history behind this temple is described on the page Religion: Hinduism. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cervus unicolor Sambar deer

This very large deer, by some authorities named Rusa unicolor, has a wide distribution in Asia, from the entire Indian Subcontinent eastwards to southern China and Taiwan, , and thence southwards through Indochina and Malaysia to Sumatra and Borneo.

The weight of a stag is typically around 350 kg, although large specimens may weigh as much as 550 kg. Hinds are smaller, weighing 100-200 kg. Populations of this deer have declined substantially in most areas, mainly due to hunting and habitat destruction. It has been introduced to various countries around the world, including Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.

The common name is derived from Sanskrit sambara (‘deer’).

Sambar stags, one with the antlers in velvet, Maha Eliya Thenna (Horton Plains) National Park, Sri Lanka. Subspecies unicolor, found in India and Sri Lanka, is the largest of the 7 accepted subspecies. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sambar stag, Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This stag, observed in Ranthambhor National Park, has had a close encounter with a tiger or a leopard, evident from the scar on the flank. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sambar deer ofte feed in the lakes of Ranthambhor National Park. This herd is resting in front of ruins of a former Rajput palace. The fierce Rajputs are described on the page Travel episodes – India 1986: “His name is Muhammad!” (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sambar stag, drinking from a lake, Ranthambhor National Park. It is raising its tail as an alarm signal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sambar deer in morning light, Sariska National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hind in evening sun, Sariska National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Portrait of a hind, which is much bothered by flies, Ranthambhor National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calf, reflected in a lake, Ranthambhor National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Suckling calf, Ranthambhor National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sambar deer, grazing on succulent water plants in a lake, Ranthambhor National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This hind is feeding in a swamp in Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. Painted storks (Mycteria leucocephala) are nesting in the tree in the background. One of the storks is spreading its wings like two large fans. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A hind and her calf quenches their thirst at a waterhole, Sariska National Park. The monkeys to the right are northern plains langurs (see above). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A rufous treepie (Dendrocitta vagabunda) is using the back of this hind as a lookout post, Sariska National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Drinking hinds, Sariska National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On a hot September day, this hind is cooling down in a waterhole, Sariska National Park. Peafowl (Pavo cristatus) are seen in the background. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stag, enjoying a bath, Sariska National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hyelaphus

Previously, the Indian hog deer (below) and three other small Asian deer were placed in the genus Axis (above). However, genetic studies have revealed that they differ sufficiently from the spotted deer (above) to constitute a separate genus.

I have not been able to find an explanation regarding the etymology of the generic name. The last part is a Latinized version of Ancient Greek elaphos (‘deer’), and the first part may be derived from Ancient Greek hyle (‘forest’).

Hyelaphus porcinus Indian hog deer

A small deer, the buck standing about 70 cm at the shoulder and weighing about 50 kg. The doe is much smaller, standing about 60 cm and weighing c. 30 kg.

It ranges from Pakistan in a belt eastwards across the Gangetic Plain of northern India to Bangladesh and Myanmar. It has also been introduced to Australia and Sri Lanka. In Indochina and south-western China, it is replaced by the Indochinese hog deer (H. annamiticus).

The specific name, from Ancient Greek porkos (‘pig’ or ‘hog’), was given in allusion to the hog-like manner, in which it runs through the forest, with the head stretched forward, so that it can duck under obstacles instead of leaping over them.

Hog deer and a single spotted deer (see above), eating soil to obtain minerals, Rapti River, southern Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hog deer buck, his antlers in velvet, Rapti River. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hog deer does, Kaziranga National Park, Assam (top), and Corbett National Park, Uttarakhand. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hog deer, drinking from a rainwater puddle, Corbett National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Muntiacus Muntjac, barking deer

This genus of small deer, comprising 12 species, is native to Asia, occurring from India and Sri Lanka eastwards to southern China and Taiwan, and thence southwards to the Indonesian Archipelago.

Males are characterized by their short antlers, often only about 10 cm long. Instead of using their antlers, they tend to fight for territory with their 2-4 cm long upper canines. Where the males have antlers, the females have small bony knobs with tufts of fur.

The generic name is a Latinized form of the Dutch name of these animals, muntjak, which is a corruption of their Sundanese name, mencek. The popular name barking deer was given in allusion to their alarm call, which is reminiscent of a dog’s barking.

Muntiacus muntjak Indian muntjac

This very widespread animal, in Hindi known as kakar, is distributed from India and Sri Lanka eastwards to southern China, and thence southwards through Indochina and Malaysia to Java and Bali. 15 subspecies have been described. In the Himalaya, it is found up to elevations around 2,500 m.

Indian muntjac buck with antlers in velvet, between Sherpagaon and Surkhe, Lower Langtang Valley, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Indian muntjac doe in dense vegetation, Begnas Tal, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Does, Corbett National Park, Uttarakhand. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Indian muntjac in captivity, Melamchi Phul, Helambu, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rucervus

This genus is an ancient lineage that, together with the genus Axis (above), represents the oldest radiation in the subfamily Cervinae. It was originally proposed as a subgenus of Cervus by British naturalist and ethnologist Brian Hodgson (1801-1894), based on antler shape. Today, the genus has a single member, the barasingha (below), as the only other member, Schomburgk’s deer (R. schomburgki) of Indochina, is probably extinct.

The generic name is a combination of two other genus names, Rusa, which means ‘deer’ in Malay, and Cervus (above).

Rucervus duvaucelii Barasingha, swamp deer

In the 1800s, this species ranged from Pakistan eastwards across northern and central India and southern Nepal to Bangladesh and north-eastern India. However, due to uncontrolled hunting and habitat loss, the population is today highly fragmented, with scattered herds found in southern Nepal and in Uttar Pradesh, Assam, and Madhya Pradesh. It is extinct in Pakistan and Bangladesh.

This deer differs from all other Indian species in that the antlers carry more than 3 tines, giving rise to the Hindi name barah singga, meaning ‘twelve-horned’. Mature stags usually have 10-14 tines, but up to 20 has been recorded.

Three subspecies have been described. The western nominate race has splayed hooves, an adaptation to live in flooded grasslands in the Indo-Gangetic plain. Today, a population of about 2,000 live in scattered locations in Uttar Pradesh, and about 2,200 in the Sukla Phanta Wildlife Reserve in western Nepal.

The eastern subspecies ranjitsinhi is restricted to the north-eastern state of Assam, where the population was as low as about 700 in 1978. Since then, numbers have been steadily rising due to conservation efforts. In 2016, it was estimated that about 1150 individuals were present in Kaziranga National Park. A few also live in Manas National Park and other protected areas.

The southern subspecies branderi differs from the other subspecies in having hard hooves, an adaptation to live in open forest with an understorey of grass. Formerly, it was restricted to Kanha National Park in Madhya Pradesh, where only about 750 individuals survive. Lately, it has been reintroduced to Satpura Tiger Reserve, likewise in Madhya Pradesh.

The specific name commemorates French naturalist and explorer Alfred Duvaucel (1793-1824), who died in India, only 31 years old. Rumours had it that he was killed by a tiger.

Barasingha stags, subspecies branderi, in morning light, Kanha National Park, Madhya Pradesh. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Barasingha stags, Kanha National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Barasingha stags in evening light, Kanha National Park. The bird is a black drongo (Dicrurus macrocercus). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Barasingha hind in evening light, Kanha National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Herd of eastern swamp deer, ssp. ranjitsinhi, Kaziranga National Park, Assam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young eastern swamp deer stag in evening light, Kaziranga National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hind and calf, Kaziranga National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cricetidae Voles and allies

This huge family of small to medium-sized rodents includes voles, lemmings, hamsters, and New World rats and mice, counting about 112 genera and 600 species. They are distributed in Europe, Asia, and the Americas.

Alticola

A small Asian genus of voles, counting about 12 species.

The generic name is derived from the Latin altus (‘high’) and colo (‘to inhabit’), thus ‘the one that lives at high altitudes’.

Alticola stoliczkanus Stoliczka’s mountain vole

This vole lives in high altitude desert areas in Tibet and in the northern outskirts of the Himalaya in Pakistan, India, and Nepal.

The specific name was given in honour of Ferdinand Stoliczka (1838-1874), a Czech palaeontologist, geologist, and zoologist, who mainly worked in India. He died of altitude sickness during an expedition to the Karakoram Mountains.

Stoliczka’s mountain voles live in burrows. – Tso Kar, Ladakh (upper 2), and Shigatse, Tibet. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stoliczka’s mountain vole, basking in the sun outside its burrow, Shigatse, Tibet. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is stretching out on a patch of bare, salt-encrusted soil to suck up the warmth from the morning sun. – Tso Kar, Ladakh. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“There were white-tusked wild males, with fallen leaves and nuts and twigs lying in the wrinkles of their necks and the folds of their ears; fat, slow-footed she-elephants, with restless, little pinky black calves only three or four feet high running under their stomachs; young elephants with their tusks just beginning to show, and very proud of them; lanky, scraggy old-maid elephants, with their hollow anxious faces, and trunks like rough bark; savage old bull elephants, scarred from shoulder to flank with great weals and cuts of bygone fights, and the caked dirt of their solitary mud baths dropping from their shoulders; and there was one with a broken tusk and the marks of the full-stroke, the terrible drawing scrape, of a tiger’s claws on his side.

They were standing head to head, or walking to and fro across the ground in couples, or rocking and swaying all by themselves – scores and scores of elephants.”

From Toomai of the Elephants, a story in The Jungle Book (1894), by English author and journalist Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936).