Reptiles and amphibians in the Indian Subcontinent

Rock python (Python molurus), basking in the sun outside its den, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. Formerly, this den was probably inhabited by a family of Indian porcupines (Hystrix indica), which may have deserted it – or the python simply chased them away. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

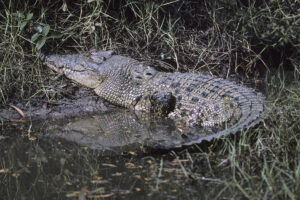

Saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), Maipura River, Bhitarkanika Wildlife Reserve, Odisha. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The red-spotted agama (Paralaudakia himalayana) is very common in Ladakh. This one is sitting on a stone wall in the town of Leh. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sri Lankan green whip snake (Ahaetulla nasuta), Tissawewa, near Hambantota, southern Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male brown-patched kangaroo lizard (Otocryptis wiegmanni), Sinharaja Forest Reserve, south-western Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea), digging a nesting hole on a sandy beach, Hikkaduwa, south-western Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This page deals with a selection of reptiles and amphibians, which I have encountered during several visits to the Indian Subcontinent since 1974. Within each of the two groups, families, genera, and species are presented in alphabetical order.

A number of pictures, depicting unidentified species, are also shown here. If you are able to identify any of these animals, or if you find any errors, I would be grateful to receive an email. You may use the address at the bottom of this page.

Map, showing Indian states and union territories. (Borrowed from www.mapsofindia.com)

Reptiles

Agamidae Agamas

Agamas are a large group of lizards, comprising 6 subfamilies with about 64 genera and more than 300 species, distributed in Asia, Australia, Africa, and southern Europe.

Calotes Forest lizards, garden lizards

This genus of the subfamily Draconinae contains about 29 species, native from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to southern China, and thence southwards through Indochina and Malaysia to Indonesia. The greateast diversity is found India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kalos (‘beautiful’), referring to the beautiful colours of many of the species.

Calotes calotes Southern green forest lizard

This large agamid, growing to 65 cm long including the long, slender tail, lives in forests of Sri Lanka and in montane areas of south-western India. It is bright green with white vertical stripes on the body. In the breeding season, or when excited, the male develops a bright red head and throat, and it may also become a much darker green.

Southern green forest lizard, Sinharaja Forest Reserve, Sri Lanka. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male southern green forest lizard, displaying a reddish head, Ratnapura, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calotes nigrilabris Black-cheeked forest lizard

This species is endemic to the central hills of Sri Lanka, at elevations between 1,300 and about 2,500 m. The male is easily identified by its black cheeks, whereas the female resembles the green forest lizard (above), but has black dots on the cheeks.

The specific name is derived from the Latin niger (‘black’) and labrum (‘lip’).

Male black-cheeked forest lizard, Baker’s Falls, Maha Eliya Thenna National Park (Horton Plains), Sri Lanka. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female black-cheeked forest lizard, Maha Eliya Thenna National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female black-cheeked forest lizard, Pidurutalagala, central Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calotes versicolor Oriental garden lizard

This species is also known as changeable lizard, or bloodsucker, the latter name alluding to the bright red head and throat of the male in the breeding season, or when excited. It is common, living in a wide range of habitats, including urban areas.

It is distributed from eastern Iran and Afghanistan eastwards across the entire Indian Subcontinent to southern China, and thence southwards through Indochina to Sumatra. It has also been introduced to other places, including Oman, Mauritius, the Seychelles, Singapore, and the United States. In Singapore, it is a threat to the native green crested lizard (Bronchocela cristatella).

In China, it is declining due to persecution, presumably collected for food or traditional medicine.

The specific name is derived from the Latin verso (‘to turn’) and color (‘colour’), thus ‘the one that changes its colour’.

Male oriental garden lizard, sitting on bamboo poles, Andaman Islands. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

When exited, the male oriental garden lizard turns bright red on head and throat. – Sinuwa, Tamur Valley, eastern Nepal (top), Sauraha, southern Nepal (centre), and Manas National Park, Assam. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female oriental garden lizard, Andaman Islands. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This female is sitting on a bamboo pole on the roof of a storage hut, Sauraha, southern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Draco Gliding lizards

This genus of unique agamids contains about 40 species, all but one restricted to Indochina, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia. A single species (below) is found in south-western India.

Another name of these lizards is flying lizards, which is not a very descriptive name, as they are not able to truly fly, but glide from one tree to another by spreading out their ribs, which are connected by a wing-like membrane, called patagia.

The generic name is a Latinized version of Ancient Greek drakon (‘dragon’).

Draco dussumieri Malabar gliding lizard

This species is found in the Western and Eastern Ghats, from Goa and Maharashtra southwards to Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

The specific name honours French merchant and traveller Jean-Jacques Dussumier (1792-1883), who collected numerous animals in southern Asia and other regions around the Indian Ocean, from 1816 to 1840.

Female Malabar gliding lizard, Mahaveer Wildlife Sanctuary, Goa. The plant with blue flowers is a member of the family Acanthaceae. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Japalura

A genus of 8 slender species of lizards, belonging to the subfamily Draconinae. They are distributed in the northern part of the Indian Subcontinent, from Pakistan eastwards to Myanmar and the Yunnan Province of China. A number of species, which were formerly placed in this genus, have been moved to genus Diploderma.

Members of the genus Japalura are notoriously difficult to identify, and the two species mentioned below have only been tentatively identified.

Japalura tricarinata Three-keeled mountain lizard

This lizard is extremely variable, ranging from bright green to brown, often with black bands or other markings. It is distributed from central Nepal eastwards to Sikkim and south-eastern Tibet.

This male Japalura tricarinata (?) is clinging to a house wall in the village of Bagarchap, Marsyangdi Valley, Annapurna, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Japalura variegata Variegated mountain lizard

As its name implies, this species is highly variable. It is often greenish or greyish with black bands across back and legs. It is found in eastern Nepal, north-eastern India, and Bhutan.

Japalura variegata (?), photographed near Mure, Arun Valley, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Laudakia

A small genus of 10 species, restricted to Asia. 11 species, which were formerly included in this genus, have been moved to the genera Paralaudakia (below), Acanthocercus, and Stellagama.

Laudakia tuberculata Kashmir rock agama

This large lizard is bluish with a yellow belly and yellow spots on the back and flanks. It is quite common on rocks at medium altitudes in the Himalaya, found from eastern Afghanistan eastwards to south-eastern Tibet.

Male Kashmir rock agama, Kopche Pani, Lower Kali Gandaki Valley, Annapurna, central Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female Kashmir rock agama, Sekathum, Lower Ghunsa Valley, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This female Kashmir rock agama is busy digging a hole to lay her eggs in, Kopche Pani, Lower Kali Gandaki Valley, Annapurna, central Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Otocryptis Kangaroo lizards

These small agamids, comprising two species, are endemic to Sri Lanka.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek ot-, the stem of ous (‘ear’) and kryptos (‘hidden’), thus ‘with hidden ears’. The common name alludes to the very long legs of these lizards.

Otocryptis wiegmanni Brown-patched kangaroo lizard

This species lives in forests of the wet zone and lower mountains of south-western Sri Lanka, up to altitudes around 1,300 m. The male has a large, elongated, brown patch on his dewlap, whereas the very similar O. nigristigma has a black patch. The latter seems to be restricted to the dry zone of the island.

The specific name honours German herpetologist Arend Friedrich August Wiegmann (1802-1841), who described numerous species of reptiles, 55 of which are still considered valid, and he also described several new species of amphibians.

Male brown-patched kangaroo lizard, Sinharaja Forest Reserve, south-western Sri Lanka. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Paralaudakia

A small genus of 8 species, found from eastern Europe eastwards to Mongolia and western China. They were formerly included in the genus Laudakia (above).

Paralaudakia himalayana Red-spotted agama

This species is easily recognized by a red patch on both sides of the neck. It is very common in Ladakh and is otherwise widely distributed in Asia, from Turkmenistan and eastern Uzbekistan eastwards to Sinkiang, and thence southwards to eastern Afghanistan, northern Pakistan, Kashmir, and Nepal.

Red-spotted agama, sitting on a stone wall, Leh, Ladakh. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This red-spotted agama is sitting on a mani stone (a stone slab with Buddhist mantras engraved), Martselang, near Hemis, Ladakh. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Phrynocephalus Toad-headed agamas

About 44 species are distributed from the Middle East and the Arabian Peninsula eastwards to Central Asia and western India. These small agamas are adapted to a life in dry areas. When hunting, they often sit still for long periods of time, scanning the surroundings.

An unidentified species of toad-headed agama, Gyantse, Tibet. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Phrynocephalus theobaldi Theobald’s toad-headed agama

This small agama is found from Kazakhstan and Sinkiang southwards across the Tibetan Plateau to Ladakh and northern Nepal, living in desert, grassland, and among shrubs.

The specific name was applied in honour of British naturalist William Theobald (1829-1908), a staff member of the Geological Survey of India in Myanmar, which was then a part of British India. He described about a dozen new species of reptiles, and was the first person to publish a catalogue of the reptiles, which had been collected in British India. His work on Indian freshwater snails was one of the first of its kind, and he made his shell collections available to American missionary and naturalist Francis Mason (1799-1874) for his epic work Burmah, its People and Natural Productions, of which the third edition was completely rewritten by Theobald.

Theobald’s toad-headed agama, Tso Kar, Ladakh. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Theobald’s toad-headed agama, Puga Marshes, Ladakh. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Boidae Boas

This family of non-venomous snakes, comprising 15 genera and about 54 species is found in the Americas, Africa, Europe, and Asia, and on some Pacific islands. The greatest diversity is in the Americas.

Eryx Old World sand boas

Members of this genus, counting about 13 species, are distributed in south-eastern Europe, in northern Africa, southwards to Central African Republic and Tanzania, in the entire Arabian Peninsula, and in Asia, eastwards to Mongolia and the Indian Peninsula.

In Greek mythology, Eryx was a legendary king in northern Sicily, in the province today known as Erice.

Eryx conicus Rough-scaled sand boa

This species, also known as Russell’s boa or rough-tailed sand boa, is widely distributed in drier areas of the Indian Peninsula and northern Sri Lanka. It preys on birds and small mammals, which it kills by constricting.

Rough-scaled sand boa, Sariska National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chamaeleonidae Chameleons

This family of unique reptiles, comprising 12 genera with more than 200 species, is distributed in Africa, Madagascar, southern Spain, Corsica, Sardinia, southern Italy, southern Greece, the Near East, the Arabian Peninsula, southern India, and Sri Lanka. The vast majority of the species are found in Africa south of the Sahara, and in Madagascar.

The eyes of these animals move independently, and they are able to analyze two different images simultaneously when hunting for prey. When a suitable prey has been spotted, the chameleon projects its very long, sticky, folded-up tongue at a tremendous speed at the prey, often from quite a distance. The poor victim sticks to the tongue, which is then folded up and retracted into the mouth, prey and all.

Chameleons are also able to change colour very fast, which mostly happens when they get excited. An example is shown on the page Reptiles and amphibians: Reptiles in Africa, under Chamaeleo dilepis.

The family name is derived from the Greek khamai (‘on the ground’) and leon (‘lion’), thus ‘earth-lion’, undoubtedly alluding to the hunting method and voracious appetite of these animals.

Several species are popular pets, and some places they have escaped (or have been released) to form feral populations, which are often a threat to the local insect fauna – and thereby indirectly to insectvorous birds, and plants which are dependent on insects for pollunation. This is seen in Hawaii and other places.

Chamaeleo

Today, this genus contains about 14 species. Previously, it was much larger, but the major part of the species have been moved to other genera.

Chamaeleo zeylanicus Indian chameleon

This species occurs in extreme south-eastern Pakistan, in the Indian Peninsula south of the Ganges River, and in western Sri Lanka. It is widely separated geographically from other members of the family. Presumably, in the distant past, a species of chameleon drifted on a tree trunk across the Indian Ocean from the East African coast or the Arabian Peninsula.

The specific name refers to Sri Lanka, called Ceylon in the British colonial time. The type specimen was collected here.

Indian chameleon, Guindy National Park, near Chennai, Tamil Nadu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cheloniidae Sea turtles

Of the world’s 7 species of sea turtles, 6 belong to this family. These animals are characterized by having shields covering back and belly, firmly attached to vertebra and ribs. The back shield is called a carapax, the belly shield plastron. Both shields are covered in scutes, consisting of horn-like keratin. The scutes on the back are arranged in 3 longitudinal rows.

The seventh species is the huge leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), which forms a separate family, Dermochelyidae. It has no scutes, but a leathery skin that covers 5 or 7 longitudinal ribs along the back.

Although sea turtles spend about 98% of their life in the oceans, the females must get ashore, when they are about to lay eggs. With a great effort, they crawl ashore on a sandy beach, where they use their hind flippers to dig a hole above the high tide line.

When a female has finished digging, she lays a number of white eggs, often between 80 and 100. They resemble table tennis balls, but are soft, so as not to break when they fall into the hole. When the egg-laying is over, the female covers the eggs, throwing sand about with her flippers to camouflage the spot. Then she returns to the sea.

Some sea turtle species lay eggs several times in a season, in some cases up to 11 clutches. It sounds incredible, but the female often returns to the beach where it hatched many years before. How she is able to do that remains a mystery. One theory is that the animals are imprinted by the physical and chemical composition of the beach, and that they are able to use the Earth magnetism to navigate from.

Earlier, adult sea turtles didn’t have many enemies. Tidligere havde voksne havskildpadder ikke mange fjender. Large sharks and orcas (Orcinus orca) may take some, although it is a rather bony mouthful. However, with the spreading of humans to the entire planet, the situation is quite different, and all eight species are declining drastically. The eggs are dug up and eaten by poor settlers, or eaten as a delicacy in restaurants, or because they are regarded as an aphrodisiac. Many adult turtles are also eaten by people.

The hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) is persecuted due to its beatiful carapace, from which jewelery, combs, and other items are carved. Numerous carapaces are imported by the Japanese. Even entire, varnished carapaces are sold as souvenirs, among other places in Indonesia.

Tens of thousands of sea turtles drown in fishing nets or become damaged by the propellors of boat engines. Young turtles die from eating waste oil and lumps of tar, floating on the surface. Many leatherbacks eat plastic, which resembles their main food, jellyfish. The plastic cannot be digested and gets stuck in the intestines, causing the animal to die from starvation.

The characteristic tractor-like tracks from an egg-laying sea turtle, Hambantota, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Robbed sea turtle nest, Andaman Islands. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lepidochelys Ridleys

A small genus of 2 species, the olive ridley (below) and the endangered Kemp’s ridley (L. kempii), which is restricted to the Gulf of Mexico.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek lepidos (‘scale’) and chelys (‘turtle’), perhaps alluding to the scaly appearance of the head and flippers of these animals. The common name is of unknown origin.

Lepidochelys olivacea Olive ridley

This rather small species, growing to about 75 cm long, is the most abundant of all sea turtles. It occurs in all warmer seas, primarily in the Pacific and Indian Oceans. It is known for its spectacular synchronised mass nesting, called arribada (Spanish for ‘arrival’), where thousands of females gather on the same beach to lay eggs. Two of these places are Playa Ostional, Guanacaste Province, Costa Rica, and Odisha, eastern India (see below).

The specific name alludes to the olive tinge on this otherwise brownish or greyish animal.

A female olive ridley usually lays between 80 and 100 white eggs, which resemble tabletennis balls. – Hikkaduwa, south-western Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

When the female has finished laying eggs, she covers them by scraping sand over them with her flippers. – Maipura River delta, Odisha. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

When she has finished, she creeps back to the sea. – Hikkaduwa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young olive ridleys, hatched at a breeding centre for ridleys, Mayabunder, Andaman Islands. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This olive ridley was caught by fishermen off the coast of Sri Lanka. Shortly after, it was slaughtered and eaten. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Catching olive ridleys

Wheeler Island is a small island in the mouth of the large Maipura River in Odisha. On this island is a cluster of small thatched huts, in which fishermen live part of the year. In one of these huts, Indian biologist Bivash Pandav from the Wildlife Institute of India stayed together with his staff each autumn in the period 1994-1999.

In this area, Pandav was studying the life and ways of the olive ridley. In November-December, thousands gather off this coast to mate. He tried to estmate the number of egg-laying females, the number of which varies significantly from year to year. In 1994, it was estimated that about 525,000 females came ashore at Gahirmata. In 1999, the number was more than 200,000. Today, only Costa Rica has similar numbers.

Pandav and his staff also counted turtles, which had drowned in fishing nets, had been thrown overboard, and then drifted ashore. When a specimen was found, the month of observation was painted on the shield to avoid counting it again. In the period December 1993 to April 1994, 5,282 animals, which had drifted ashore, were counted along the coast of Odisha. In later years, the numbers have been even higher.

Finally, Pandav and his staff tagged as many turtles as possible to follow their wandrings. A steel ear-mark, used for pigs, was attached to one of the front flippers, using a plier. Each tag had a number and the address of the Wildlife Institute. During the 1990s, Pandav and staff tagged almost 15,000 turtles. Recoveries indicate that a large part of the population reside in Sri Lankan waters outside the breeding season.

While it is easy enough to tag the females, when they come ashore to lay eggs, it is far more difficult to catch the males. In reality, it can only be done when the animals mate, as they are then oblivious of the presence of people.

I met Pandav in India in October 1997, and when he realized that I was very interested in his work, he kindly invited me to join him and his staff on Wheeler Island, and a few weks later I went there.

From the island, we went to sea in a small motorized vessel named Maa Panchu Barahi (named after a local Hindu goddess). Choppy waves made the boat very unsteady, making it difficult to spot the turtles. However, the staff had eyes like hawks and spotted a pair at the surface at regular intervals.

When a pair was spotted, the helmsman turned the engine on full speed, steering towards the pair, while the other staff members made the gear ready, which was simply a net, made from nylon strings and attached to a triangular frame of robust bamboo stems. From two of these stems, ropes were tied to small projections on the rails of the boat.

To me, it seemed that the boat would run over the pair, but at the last instant the helmsman turned it to the right, and the assistant with the net steered it under the pair, which got entangled in the ropes.

”Pull!”, he shouted, and the other two staff members pulled hard at the ropes to attach the net to the rail. If this was not done quickly, the turtles might jump out of the net. But everything went well, and one of the turtles was lifted into the boat.

Besides tagging the turtles, length and width of the shield were measured, and the turtle was lifted into a net, which was then hung on a hook, attached to a scale. The scale was hanging from a pole, which two of the men lifted onto their shoulders. As it turned out, an olive ridley weighs between 35 and 50 kilos.

Later in the day, while the men were busy with a turtle in the net, I asked Pandav:”Did you ever catch one of your tagged turtles from the previous years?”

”Not yet”, he said.

At the same instant, one of the men shouted: ”This one is tagged!”

Pandav ran to have a look at the tag, and then performed a veritable war dance on the deck.

”This one was tagged last year!” he said happily.

In the course of the day, we caught 24 pairs – a personal record for Pandav. ”You bring me luck!” he said.

Late in the day, we returned to Wheeler Island, exhausted but elated. It had been a fine day for all of us.

Indian biologist Bivash Pandav (left) and his staff on the lookout for olive ridleys off the coast of Odisha. In front is the net to catch the mating pairs. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A mating pair of olive ridleys. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pandav’s assistant steers the net under a pair, which gets entanglet in the ropes. This pair is still mating. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A ridley is pulled into the boat and placed on an old car tyre to get measured. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pandav’s staff, weighing a ridley. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A steel ear-mark, used for pigs, is attached to one of the front flippers, using a plier. Each tag has a number and the address of the Wildlife Institute of India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Colubridae Grass snakes, keelbacks, and allies

This is the largest family of snakes, comprising over 250 genera and more than 2,100 species. They are found on all continents, except Antarctica.

Members of the family are non-toxic, with a few exceptions, including the genus Rhabdophis (below).

Ahaetulla Asian whip snakes, Asian vine snakes

These slender snakes, counting about 19 species, are diurnal and arboreal, and they are thought to be mildly venomous. However, they are not at all aggressive. They are found from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to southern China, and thence southwards to the Philippines and Indonesia.

In later years, many species have been split into several separate species, and many of these have a very restricted range. The greatest diversity is found in southern India.

The type specimen was described from Sri Lanka, and the generic name was adapted from the Sinhalese name of these snakes, Aheatulla, which means ‘eye-plucker’ – whatever that may refer to.

Ahaetulla nasuta Sri Lankan green whip snake

As of today, this species is endemic to western and southern Sri Lanka. It was once thought to have a much larger range, in India, Sri Lanka, and Southeast Asia.

The specific name is derived from the Latin nasus (‘nose’) and utus, a suffix forming adjectives, thus ‘with a (long) nose’.

Sri Lankan green whip snake, Sinharaja Forest Reserve, south-western Sri Lanka. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sri Lankan green whip snake, Tissawewa, near Hambantota, southern Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chrysopelea Flying snakes

A genus of 5 species, distributed from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to southern China, and thence southwards to the Philippines and Indonesia.

The common name refers to the fact that these snakes are able to glide from one tree to another by spreading out their ribs, giving the impression of flying.

The first part of the generic name is derived from Ancient Greek khrysos (‘gold’), alluding to the splendid colours of the type species, the golden tree snake (below). What the last part refers to is not known.

Chrysopelea ornata Golden tree snake, golden flying snake

This beautiful snake is widely distributed, found from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to southern China, and thence southwards through Indochina to the Malay Peninsula.

Due to its gorgeous colours, it is a very popular pet.

Golden tree snake, Sigiriya, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dendrelaphis Bronzeback tree snakes

A large genus with about 50 species, distributed from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to southern China, and thence southwards to New Guinea, Australia, and the Solomon Islands.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek dendron (‘tree’) and elaphe, the classical Greek word for non-venomous snakes, in particular the Aesculapian snake (Zamenis longissimus), named after Asclepius, the god of medicine in Greek mythology. This snake was considered a symbol of healing.

Dendrelaphis tristis Common bronzeback tree snake

This slender snake is widely distributed in the Indian Subcontinent, and also occurs in Myanmar.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘sad’. Why this name was applied to a colourful snake is quite a mystery.

Common bronzeback tree snake, Sinharaja Forest Reserve, Sri Lanka. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ptyas Rat snakes

A genus of 13 species, found in warmer areas of Asia. The generic name is a misnomer. It is derived from Ancient Greek ptyas (‘the one who spits’), referring to a kind of snake believed to spit venom in the eyes of humans. However, no member of this genus is known to spit venom.

Ptyas mucosa Oriental rat snake

This is a large snake, often exceeding 2 m in length, with some recorded specimens measuring up to 3.7 m. It is distributed from Turkmenistan and eastern Iran eastwards across the entire Indian Subcontinent to southern China, and thence southwards through Southeast Asia to the Indonesian islands Sumatra and Java.

In the Himalaya, it may be found up to an elevation of about 2,000 m.

Oriental rat snake, observed along the Vishnumati River, Kathmandu, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rhabdophis Keelbacks

A genus of the subfamily Natricinae, comprising about 27 species, which are primarily distributed in Southeast Asia.

Rhabdophis himalayanus Himalayan keelback, orange-collared keelback

This keelback is highly variable and may be almost black, reddish or pale olive-brown, often with numerous black, brown, and yellow spots. A whitish, yellow, or orange stripe stretches from the mouth beneath the eye to the hindneck, forming a collar. The underside is yellowish or reddish, speckled with brown or black.

This species is distributed from central Nepal and Bangladesh eastwards across northern Indochina to southern China. In the Himalaya, it is mostly encountered at lower elevations.

Himalayan keelback, Gul Bhanjyang, Helambu, central Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Xenochrophis Keelbacks

This small genus, likewise called keelbacks, contains 5 species, found from Pakistan and northern India eastwards to Indochina, and thence southwards to Indonesia.

Xenochrophis cerasogaster Painted keelback

This species, also known as dark-bellied marsh snake, is found from Pakistan across northern India, Nepal, and Bangladesh to north-eastern India.

It is quite variable, brown or blackish above, with or without darker spots, and with a yellow, more or less distinct band on each side, from the mouth to the end of the tail.

Painted keelback, observed at Tungnath, Uttarakhand. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Crocodylidae Crocodiles

These huge reptiles, altogether about 17 species in 3 genera, are widely distributed in tropical areas, with 3 species in Africa and western Madagascar, 9 species in Asia, New Guinea, and northern Australia, and 5 in the Americas.

Crocodylus Typical crocodiles

A genus of 13 or 14 species, distributed in warm areas across the globe. The status of the Bornean crocodile (C. raninus or C. porosus ssp. raninus), remains unclear.

The generic name is derived from krokodeilos, the Ancient Greek term for these animals.

Crocodylus palustris Marsh crocodile, mugger crocodile

This crocodile occurs in the Indian Subcontinent, including Sri Lanka, and also in southern Iran. It lives in freshwater habitats, preferring slow-moving, shallow waters.

The largest known specimen measured 5.63 m, but on average males reach a length of 3-3.5 m, females 2-2.5 m, males weighing up to 200 kg. Its numbers have decreased alarmingly during the last 50 years due to habitat destruction (dam building and conversion of wetlands to farmland). They occasionally get entangled in fishing nets and drown, and some are killed by fishermen who regard them as competitors. In 2013, it was estimated that less than 8,700 individuals were living in the wild.

The word mugger is in fact pronounced ‘magar’, the Hindi name of this animal, derived from the Sanskrit makara, referring to a mythical crocodile-like creature.

The specific name is derived from the Latin palus (‘marsh’ or ‘swamp’).

Marsh crocodile, basking on the shore of the Rapti River, southern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Marsh crocodile, Kasara Crocodile Breeding Centre, Chitwan National Park, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young marsh crocodile, caught in a fishing net, Bolgoda Lake, south-western Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Crocodylus porosus Saltwater crocodile

As its name implies, this species is living in coastal areas, from south-eastern India and Sri Lanka eastwards to Indochina, and thence southwards through Indonesia and the Philippines to New Guinea and surrounding islands, and northern Australia.

It is the largest living reptile, males sometimes growing more than 6 m long and weighing up to 1,300 kg. Females are much smaller, rarely exceeding 3 m in length. The largest specimens occasionally turn into dangerous man-eaters.

The specific name is derived from the Latin porus (‘an opening’), thus ‘having pores’. What it refers to is not clear.

Saltwater crocodiles in captivity, Port Blair Zoo, Andaman Islands. The uppermost picture shows a male and a female, the lower two a juvenile. The rest are sub-adults. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Elapidae

A huge and diverse family of snakes, comprising 55 genera with about 360 species, including highly venomous groups like mambas, cobras, kraits, and sea snakes. They are characterized by their permanently erect fangs at the front of the mouth.

These snakes live in tropical and subtropical regions around the world, with terrestrial forms in Asia, Australia, Africa, and the Americas, and marine forms in the Pacific and Indian Oceans. They vary greatly in size, from the king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah), which may sometimes grow almost 6 m long, to the white-lipped snake (Drysdalia coronoides), which is a mere 18-20 cm long.

Naja True cobras

Following several revisions, this genus now contains about 38 species, distributed in the entire Africa, southern Arabia, and from Turkmenistan and Iran eastwards across the Indian Subcontinent to southern China, and thence southwards to Indonesia and the Philippines. The greatest diversity is in Africa.

The generic name is derived from naga, the Sanskrit name of the Indian cobra (below).

Naja naja Indian cobra

This well-known snake is found in the entire Indian Subcontinent, but nowhere else.

This boy makes a living by performing for people, playing his flute, while his cobra is ‘dancing’ in rhytm with the movements of the flute. It is a myth that the snake moves in rhythm with the music, as snakes have a limited sense of hearing. – Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gavialidae

A small family of crocodile-like reptiles, comprising only two members, the gharial (below) and the false gharial (Tomistoma schlegelii), both living in Asia.

Gavialis gangeticus Gharial

This animal resembles a crocodile, but its snout is long and slender, with 110 sharp, interlocking teeth – a perfect adaptation for catching fish. Males may grow very large, to 6 m long, whereas females are smaller, to 4.5 m long. It lives in rivers in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, only leaving the water to bask in the sun, or to dig a nest in a sandy shore.

The generic and common names both refer to a distinct lump that the adult male has at the end of the snout, which resembles a clay pot, known as a ghara. This lump is hollow, amplifying a hissing sound that the male emits, which can then be heard far away. The specific name means ‘living in the Ganges’.

The gharial population has declined drastically since the 1930s, and the current number may be less than 1,000 individuals. It is listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List.

Gharial, Rapti River, southern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male gharial, basking in the sun, Ramganga River, Corbett National Park, Uttarakhand. The lump on the tip of the snout gave rise to its name (see text). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Captive gharial, displaying its long rows of formidable teeth, Kasara Crocodile Breeding Centre, Chitwan National Park, Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gekkonidae True geckos

This is the largest family of geckos, containing over 950 species in 64 genera.

The name gecko stems from the call of the Southeast Asian tokay gecko (Gekko gecko), rendered as geck-oo or tuc-too.

Hemidactylus

Geckos of this genus are often called house geckos, as many of the species have adapted to a life inside houses. They are native to most tropical areas of the world, and a few species are also found in subtropical parts of Europe and Africa. Presently, about 190 species are known, with new species being described every few years.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek hemisys (‘half’) and daktylos (‘finger’). According to one source, it probably refers to the rows of skin folds under the digits of these geckos, which are grouped in two halves.

Hemidactylus whitakeri Whitaker’s termite hill gecko

This species, described as late as 2018, is restricted to Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.

The specific name honours American-born Indian herpetologist and wildlife conservationist Romulus Earl Whitaker (born 1943), founder of the Madras Snake Park, the Andaman and Nicobar Environment Trust, and the Madras Crocodile Bank Trust, in recognition of his valuable contribution toward the study and conservation of reptiles and other wildlife in India.

Whitaker’s termite hill gecko, sitting on a metal door, south of Mysore, Karnataka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Geoemydidae

A large and diverse family with about 19 genera and altogether around 70 species of turtles, living in freshwater and coastal areas, and forests. Most are herbivorous, but some are omnivorous or carnivorous. These animals are found in tropical and subtropical areas of Eurasia and North Africa, with a single genus in Central and South America.

Melanochelys

This small genus contains only two species, the Indian pond terrapin (below) and M. tricarinata, which is restricted to southern Nepal, north-eastern India, and Bangladesh.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek melas (‘black’) and chelys (‘turtle’). Some individuals seem almost black, other are brown or reddish.

Melanochelys trijuga Indian pond terrapin

A widespread species, found in the Indian Subcontinent, including the Maldives, in Myanmar, and also on the Chagos Islands, where it may have been introduced.

The specific name is derived from the Latin tri– (‘three’) and iugum (‘collar’), perhaps referring to wrinkles on the neck.

Indian pond terrapin, Corbett National Park, Uttarakhand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pythonidae

This family contains 10 genera and about 40 species of non-venomous snakes, which kill their prey by constricting it. They are found in Africa, and from India eastwards to Indochina, and thence southwards to New Guinea, Australia, and the Bismarck Islands, with the largest diversity in Indonesia and Australia.

Python

A genus with 10 species, distributed in Africa south of the Sahara, and in the Indian Subcontinent, Indochina, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

In Ancient Greek mythology, Python was a huge serpent (sometimes depicted as a dragon), born by the mother goddess Gaia. Python resided in the temple at Delphi, which by the Ancient Greeks was regarded as the centre of the Earth, represented by a stone, which Python guarded.

In his book Fabulae, Roman author Gaius Julius Hyginus (c. 64 B.C. – 17 A.D.) relates that Zeus made love to the goddess Leto. Zeus’s wife Hera got jealous, and when Leto was about to give birth to Apollo and Artemis, Hera made Python pursue Leto, so that she was unable to deliver. However, Leto managed to give birth to the twins, and when Apollo grew up, he wanted to avenge his mother. He travelled to Mount Parnassos, where the monster dwelled, and chased it to the Gaia Temple in Delphi, where he killed it with his arrows.

Apollo with the slain Python. A 1581 engraving by German printmaker Virgil Solis (1514-1562) in Metamorphoses, by Roman poet Publius Ovidius Naso (43 B.C. – c. 17 A.D.), better known as Ovid. (Public domain)

Python molurus Indian rock python

This very large and thick snake may grow to 3 m long. It is found in the entire Indian Subcontinent, and also a few places in Indochina.

The specific name refers to a person in Greek mythology, Molouros, son of Arisbas.

Indian rock python, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

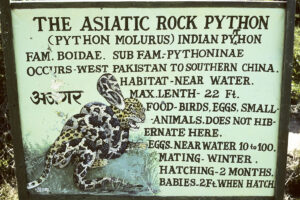

As is obvious from this info sign in Keoladeo National Park, the rock python is a formidable predator. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Scincidae Skinks

A huge, almost worldwide family, counting about 1,500 species of small to medium-sized lizards, many with smooth and shiny scales.

The family and common names are adapted from the Ancient Syriac word for these animals, sqinqur.

I have not been able to identify any of the skinks that I encountered in India and Nepal.

Skinks, basking on a rock, Kilanmarg, Kashmir. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rohtang Pass, Himachal Pradesh. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Skink, basking in the sun, sitting on a stone wall, Kuldi Ghar, Annapurna, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This skink, sitting on a stone wall, is shedding its skin, Ulleri, Annapurna, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Testudinidae Tortoises

Tortoises, comprising about 18 genera with around 50 living species, are distributed on all continents, except Australia and Antarctica. They vary greatly in size, from the famous Galapagos giant tortoise (Chelonoidis niger), which grows to more than 1.5 m long and weighs up to 400 kilos, to dwarves with a length of less than 10 cm.

Geochelone Star tortoises

A small genus with only two species, the Indian star tortoise (below), and the Burmese star tortoise (G. platynota), which is restricted to Myanmar.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek geo (‘earth’) and khelone (‘tortoise’).

Geochelone elegans Indian star tortoise

This spectacular tortoise, which is restricted to the Indian Subcontinent, was named after the star-like pattern on each of a number of characteristic humps on the shield. The ground colour is black in younger individuals, changing to brownish with age. It was once common, but is now threatened by habitat loss and illegal export for the pet trade.

Indian star tortoises, a younger specimen with black ground colour (top), and an adult with brown ground colour, Wilpattu National Park, Sri Lanka. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Adult Indian star tortoises, near Hambantota, Sri Lanka. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Trionychidae Softshell turtles

This family contains 13 genera with about 35 species of turtles, living in areas of freshwater and brackish water. Members of the family occur in Africa, Asia, and North America. Traditionally, most species were included in the genus Trionyx, but the vast majority have been transferred to other genera, leaving only a single species in Trionyx.

The common name refers to the fact that the carapace of these turtles lacks horny scales.

This turtle is tentatively identified as a young Indian peacock turtle (Nilssonia hurum), Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chitra

A small genus with 3 species, found from Pakistan eastwards to Indochina, and thence southwards to Indonesia.

The generic name is probably adapted from the Sanskrit citra, which has many meanings, including ‘strange’, ‘conspicuous’, ‘wonderful’, ‘speckled’, ‘excellent’, and ‘brightly coloured’. Make a choice!

Chitra indica Indian narrow-headed softshell turtle

This huge turtle, whose carapace may grow to more than 1 m long, lives in rivers and other freshwater habitats in Pakistan, India, southern Nepal, and Bangladesh. It is nowhere common, threatened by hunting and habitat loss.

It buries itself in sand, with only the eyes and the tip of the nose exposed, waiting for suitable prey to pass by. When this happens, its head shoots out of the shell with lightening speed, grabbing the poor victim, which may be a fish, a frog, a worm, a crustacean, a mollusc, or even a small mammal.

Indian narrow-headed softshell turtle, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. A white-throated kingfisher (Halcyon smyrnensis) is sittin on the bamboo stem. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lissemys Flapshell turtles

This small genus, containing 3 species, is distributed in the Indian Subcontinent, Myanmar, and Thailand.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek lissos (‘smooth’ or ‘plain’) and emys (‘freshwater turtle’).

Lissemys ceylonensis Sri Lankan flapshell turtle

This species is endemic to Sri Lanka. It was previously regarded as a subspecies of the Indian flapshell turtle (below). It usually has a yellow neck with black markings.

The specific name refers to Sri Lanka, called Ceylon in the British colonial time.

Sri Lanka flapshell turtle, Sigiriya, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lissemys punctata Indian flapshell turtle

This species is rather common in lakes and rivers of the Indian Subcontinent and Myanmar. In desert ponds of Rajasthan, hundreds are killed every year by drought during the very hot summer.

The specific name refers to the spotted carapace of some populations.

Indian flapshell turtles, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Typhlopidae Blind snakes

A large family of small snakes, comprising 18 genera with around 280 species. They are found in most warmer areas of the world.

The status of many of the species remains unclear due to the fact that these snakes mostly live underground. They are also called worm snakes due to their similarity to earthworms, for which they are often mistaken. However, a closer view reveals that they have tiny scales and small, indistinct eyes, covered by scales. These eyes, appearing as small dark dots, are light-detecting. They have teeth in the upper jaw.

Indotyphlops

All members but one of this genus, containing about 23 species, are native to Asia. The Brahminy blind snake (below) is widespread throughout the world.

The generic name is derived from Indo (‘Indian’), and Ancient Greek typhlos (‘blind’) and ops (‘eye’).

Indotyphlops braminus Brahminy blind snake

This species is most likely native to Africa and Asia, but has been introduced to many other parts of the world, including southern Europe, the Americas, Australia, and Oceania.

It is unique by being the only known snake to be parthenogenetic, i.e. the young are born without the eggs being fertilized by sexual male cells.

Adults grow to 10 cm long, in rare cases to 15 cm, making it the smallest known snake species.

Brahminy blind snake, Mamallapuram, Tamil Nadu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Varanidae Monitor lizards

This family is a group of about 85 species of large, carnivorous and frugivorous lizards of the genus Varanus, native to Africa, Asia, and Australia.

The family name is of Semitic origin, meaning ‘dragon’ or ‘lizard beast’. The English name is explained in various ways. Some say it has its origin due to the occasional habit of these animals to stand on their two hind legs, seemingly ‘monitoring’ something. Others say that it arose from an old superstitious belief that they would warn people of the approach of venomous animals.

My experience with the famous Komodo dragon (V. komodoensis) is related on the page Travel episodes – Indonesia 1985: Difficult journey to Komodo.

Previously, the earless monitor lizard (Lanthanotus borneensis) was placed in this family, but has since been moved to a separate family, Lanthanotidae.

Varanus bengalensis Bengal monitor lizard

This monitor can reach a length of 1.75 m, of which the tail constitutes 1 m. Males are generally larger than females, and heavy males may weigh up to 7 kg.

It is found in south-eastern Iran, Afghanistan, and the Indian Subcontinent. Previously, animals in Indochina, south-western China, the Malaya Peninsula, and Java were included in this species, but are now considered a separate species, the clouded monitor (V. nebulosus).

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘of Bengal’. Strictly speaking, Bengal is the lowland around the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta, but during the British colonial time, the term ‘Bengal’ indicated a much larger portion of northern India.

The Bengal monitor is very adept at climbing trees. This picture was taken at Lake Tissa Wewa, near Hambantota, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bengal monitors, Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bengal monitors at waterholes, Sariska National Park, Rajasthan (top) and Corbett National Park, Uttarakhand. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young Bengal monitors are more colourful than adults. These were photographed at Sigiriya (top) and Anuradhapura, both in Sri Lanka. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Viperidae Vipers, adders, rattlesnakes

A huge, worldwide family of poisonous snakes, comprising 3 subfamilies, the true or pitless vipers (Viperinae) with 13 genera and about 90 species, the pit vipers (Crotalinae) with 22 genera and about 250 species, and Fea’s vipers (Azemiopinae) with 1 genus and 2 species.

The Latin name of the pit vipers is derived from Ancient Greek krotalon (‘castanet’), alluding to the rattle on a rattlesnake’s tail. This subfamily is found in Asia and the Americas. The members, which include rattlesnakes, lanceheads, and Asian pit vipers, are distinguished by the presence of a heat-sensing pit organ, located between the eye and the nostril on both sides of the head.

Craspedocephalus Asian pit vipers

This genus, comprising about 14 species, is found from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to Indochina, and thence southwards to Indonesia. They were previously included in the genus Trimeresurus.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kraspedon (‘fringe’ or ‘tassel’) and kephale (‘head’) – whatever that may refer to.

Craspedocephalus strigatus Horseshoe pit viper

This species is restricted to montane forests in the Western Ghats in Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘furrowed’, derived from striga (‘furrow’).

Horseshoe pit viper, Periyar National Park, Kerala. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Craspedocephalus trigonocephalus Sri Lankan green pit viper

This pit viper, which is endemic to Sri Lanka, is widely distributed in the island, but is most common in the wetter south-western part, living in forests and grasslands from the lowlands up to elevations around 1,800 m.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek trigonon (‘triangle’) and kephale (‘head’), thus ‘with a triangular head’.

Sri Lankan green pit viper, Sinharaja Forest Reserve, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Amphibians

Dicroglossidae Fork-tongued frogs

This family occurs in tropical and subtropical regions, from sub-Saharan Africa eastwards through western Asia and the Indian Subcontinent to China and Japan, and thence southwards through Indochina, the Malay Peninsula, Indonesia, and the Philippines to New Guinea.

It was previously regarded as a subfamily of the family Ranidae, but was since upgraded to a separate family, containing 13-15 genera and about 210 species.

Euphlyctis

A genus with 8 species, distributed from south-western Arabia eastwards across Afghanistan and the Indian Subcontinent to Thailand and the Malay Peninsula.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek eu (‘good’ or ‘well’) and the Latin phlyctis (‘blister’). It may thus be translated as ‘well equipped with blisters’, alluding to the warty skin of these frogs.

Euphlyctis cyanophlyctis Skittering frog

This species is widely distributed, found from south-eastern Iran and southern Afghanistan eastwards across the northern part of the Indian Peninsula to extreme western Myanmar.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek kyaneos (‘dark blue’), and again the Latin phlyctis (‘blister’), thus ‘with blue blisters’. The warts on the back of this species may be green or blue (see picture below).

The common name alludes to the fact that, when disturbed, these frogs often skitter along the surface at a tremendous speed.

Skittering frogs, Rapti River, southern Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hoplobatrachus Bullfrogs, tiger frogs

A genus with 6 species, of which 5 are restricted to warmer areas of Asia, with a single species in Africa south of the Sahara.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek hoplon (‘shield’) and batrakhos (‘frog’).

Hoplobatrachus tigerinus Indian bullfrog, Indian tiger frog

This large species may grow to 17 cm long. It is native from Afghanistan eastwards across the northern part of the Indian Peninsula to Myanmar. It has also been introduced to the Andaman Islands, the Maldives, and Madagascar, where it is now a widespread invasive species and a threat to the local fauna.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘tiger-like’, alluding to the pattern on this frog.

Indian bullfrog, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rhacophoridae

A diverse family with about 23 genera and c. 440 species, occurring from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to China and Taiwan, and thence southwards to Indonesia and the Philippines, and also in sub-Saharan Africa.

Pseudophilautus Bush frogs

This genus, comprising about 80 species, is restricted to Sri Lanka and the Western Ghats. Many species are highly endangered, mainly due to habitat destruction, and about 13 species have already become extinct.

The generic name means ‘the false Philautus‘, referring to another genus in this family.

Pseudophilautus amboli Amboli bush frog

This rare species is endemic to the Western Ghats, found from southern Maharashtra southwards to Karnataka. It is small, the largest specimens measuring about 3.7 cm. It lives in forests and is critically endangered due to habitat destruction and fragmentation.

The specific name refers to the type locality in Maharashtra.

Amboli bush frog, Mahaveer Wildlife Sanctuary, Goa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Uploaded August 2023)