Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Rose of the Revolution

Rose of the Revolution

Novel by John A. Burke

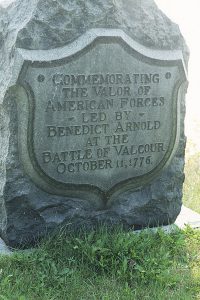

In September 2001, John and I traveled together to Lake Champlain, Fort Ticonderoga, Fort Crown Point, and other localities in up-state New York, and on to Quebec, to experience some of the sites, where Benedict Arnold and his men fought crucial battles against the British during the Revolution. We also visited localities in the Maine wilderness, where ‘The Scarecrow Army’ endured hardships beyond belief during their trek towards Quebec.

Unfortunately, John’s novel was never published, but now it is presented, unabridged, on this website, and it is my hope that you will enjoy it as much as I did. I have added a few relevant pictures here and there. I have also made minor corrections, e.g. the word ‘leftenant’ has been corrected to ‘lieutenant’, as that is the correct spelling, even though the British pronounce it as ‘leftenant’. Likewise, ‘O.K.’ has been corrected to ‘all right’, as the former was unknown in those days.

During the process of writing this novel, John was contacted by a young student, Andrea Meyer, who also had a great interest in the Culper Spy Ring. Together, they wrote an article, Spies of the Revolution, published in the magazine New York Archives, Vol. 9, No 2, 2009.

Please bear in mind that this material is copyrighted. After John’s death, his siblings and I have the entire copyright of the novel. If you would like to use parts of it for any purpose, please write to me at the following address: respectnature108@gmail.com.

Historian Pennypacker’s work was concluded on Patriot’s Day, 1964, as an historical marker was unveiled at Robert Townsend’s grave, rifles fired a long overdue salute, and the American flag fluttered in the breeze. I was the twelve-year-old Boy Scout, holding the flag on that day, and for me it began a never-ending fascination with this long-dead man and the great events, which unfolded in both my small home town of Oyster Bay and my birthplace of Manhattan. Only as an adult, however, would this interest lead me to stumble on the mystery woman at the eye of the storm, and the even more secret side to this long-secret story.

Most of the events described here took place in Manhattan, Long Island, and in the Hudson Valley. During the American Revolution, the City of New York endured the longest occupation by a wartime enemy army of any city in modern history. During these years, the average resident suffered hardships beyond our comprehension. They were forced to find ways to improvise and make do in a frightening situation, over which they had no control. Worst of all, however, was the lot of anyone labeled a traitor by the British authorities. The treatments reserved for them would result in war crimes trials today. Yet, through all of this, a few patriots chose to remain in New York, engaged in the most perilous pursuit of all – espionage. Their role was that of mice in the lion’s cage, and at times their chances of victory must have seemed just about as likely. History, of course, has been the final judge.

Getting all the facts straight hasn’t been easy. There seems to have been an invisible, sometimes cloak-and-dagger resistance against bringing this long-suppressed story to the public. Just before Pennypacker’s book went to press, several chapters of the manuscript were stolen from the safe in his publisher’s office. Taken as well were the original Revolutionary War letters from Robert Townsend’s sister Sally – a key figure in the hot debate about what really happened, when Benedict Arnold committed treason.

I ran into similar problems. During the lengthy research necessary for this book, I sometimes began to feel like a detective, re-opening an old case only to find that important pieces of the original evidence had somehow vanished, before I got there. Many of historian Pennypacker’s original documents have mysteriously disappeared from the East Hampton Library archives. Pennypacker himself came back and removed some not long before his death, at a time (in his mid-nineties) when he badly needed money. Their fate remains a mystery. Other documents have simply been stolen from the archives by persons unknown.

This intrigued me even more. Oyster Bay in the twentieth century was, after all, not unlike Oyster Bay in the Colonial Era. It is a staid town of old money families and values, in which scandal has always been un-welcome, but present. When I was a child, we played in the abandoned ruins of the Woodward estate, gaping at the shotgun blast still visible in the wall, where (it was said) a gold-digger’s wife blew the head off her wealthy, high-society husband before he could divorce her. According to two books and a TV mini-series about it, his family – incredibly – protected their son’s killer rather than allow a scandal to develop. It seems they may even have gotten the Duke and Duchess of Windsor to lie to the police about it, all in a desperate effort to stave off sensational headlines. That is how badly old families here fear scandals.

Finally, even during the American Revolution, cover stories were invented for the events contained in this book. In espionage this is frequently necessary. As a result, what has faced any truth-seeker has been the proverbial riddle wrapped inside an enigma. It comes complete with fall guys, red herrings, double agents, and invisible ink. Yet modern archives offer sufficient clues that as one orders the events chronologically and examines all the evidence, one begins identifying with the participants, and a clear picture begins to emerge. From the fog of contradictions, false statements, and cover-ups, we find – among other things – that women (on both sides) played a far more crucial role in the struggle for American Independence, than the images of Betsy Ross and Molly Pitcher would have us believe.

In researching this material, I also came to appreciate another ‘secret’ of the American Revolution. Our War of Independence probably could not have succeeded were it not for the limitless bravery and personal genius of the most effective battlefield commander in North America – Benedict Arnold. Inspiring the fledgling nation, while George Washington floundered in defeats, he was considered the second greatest hero of the American Revolution – until, that is, he married a beautiful and wealthy woman half his age. Though no one knew it at the time, that moment launched the flamboyant Arnolds on a collision course with another couple – one of infinitely lower profile. At this crucial juncture, when the American cause was experiencing its darkest hour, the question of which couple won would determine, whether or not America gained her independence.

While the final effect of their struggle is well known, the personal fates of these flesh-andblood participants have remained too long in the shadows. I have tried to let these very real individuals speak for themselves. Since some specific conversations and personal incidents are unknown, I have added a little of my own imagination in those instances, but only to flesh out the known developments. Historians always have and always will argue among themselves about what really happened at any point in the past. What can be said here is that all significant historical incidents herein seem to have happened as described and are documented directly or indirectly by information in historical archives. The picture which emerges is the only one offered to date that is consistent with all the evidence. Such cannot be said of the other versions – even the ones in the history books.

Today, as privileged citizens of one of the great democracies, we should know the true stories of a handful of real people who stepped forward when needed, prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice, and who wrestled unseen over the fragile balance of power at a time, when the lifeline of our infant republic dangled precariously. It is their daring, their shrewdness, their dedication – but most of all their passionate love for one another – that burns them into the memory and fires the imagination.

For warmth, she tried to wrap herself up in her own arms, but she could not make them move. They seemed paralyzed, as did her legs. She was lying on her back, at an angle, as though pinned. In one mighty effort she willed her arms and legs to move, and, belatedly, recognized that other feeling. Her wrists and ankles were shackled! Pain radiated from them, reminding her of previous attempts to move, which had left the skin there torn and terribly sensitive. Iron cuffs bound her to a rock! They had chafed through the skin, and salt water stung raw flesh. Now she was also conscious of the rough rock, pressing into her back. But what rock?

It was then that the first wave rolled over her mouth. Gagging, choking, she was alternately coughing and gasping for air. Another wave slapped her full in the face, but this time her mouth was closed. Water trickled down her nostrils and burned the back of her throat, but this only served to focus her. How could she have forgotten? She had to keep her mouth closed! She had to breathe sparingly, and only through her nose.

Now she remembered. The tide was rising, and she had been shackled to this rock at low tide, left there to drown, ever so slowly, under a rising tide. She clamped her mouth firmly shut. A calm resignation flooded her bloodstream, diffusing throughout the body. Strange, she thought, that one could feel calm at a moment like this. But she did. Until, that is, that the next wave forced jets of water down her nostrils. She was drowning! Calm was replaced by panic. She was drowning, one wave at a time, and there was no way she could stop it. She shut her eyes and felt the cold and the fetters, and the rock at her back. Odd, though, she thought, the rock also felt like straw, like ticking, like a cheap mattress. On her arms, she felt hands now, and a scratching, like coarse wool. And there was a new sound – shouting! The hands were pulling her up, while they continued to shout at her.

“Get up, you traitorous bitch, get up!”

And her eyes opened, not to blue, but black. Her eyes were met by darkness, broken slightly by something that seemed like candle light. Yes, she could smell the candle, it was a lamp. And she was in her bed, not the water! She opened her mouth and was able to breathe through it. She was alive! It had only been a dream! But all the while, the hands pulled at her, and the shouting continued. They wanted her out of bed and fast, that much was obvious. Fine! What did she care? She was alive! And she was awake. It had only been a dream.

She struggled to her feet, feeling the flagstones through her stockings, but the hands now gripped both her arms so tightly that it hurt. They pulled her forward and she stumbled, so they dragged her by the arms now, cursing her.

“That won’t help you none, Missy, you’re going, whether you walk or we drag you!”

Then she saw it. In the dim light of the lamp, which one of them held aloft, she saw the color of their jackets, and it was red – scarlet red. It all came back to her now. She remembered why they wanted her, and where they were taking her. She knew, and her knees now failed her completely. They cursed her while dragging her down the flagstone hallway, pulling her forcibly into the light of the overhead lamp at the first door, manned by the sick one. The old redcoat in charge of the door smiled his toothless grin.

“Going for a little sunrise swim, are we, Missy?” And he coughed out that gurgling, phlegm-filled laugh that she had come to despise during the past weeks. In response, she spat in his face. He slapped her hard across the cheek, and she tasted blood. The other guards pulled her on.

“Now, leave her alone, Silas! She’ll get what’s coming to her shortly!” With that, they dragged her through the doorway and into the courtyard, but then stopped. She breathed deep, gulping the fresh, clean air of morning. She had always loved the feel of the air at this, her favorite time of day. But she knew now that, after this morning, she would never breathe it again. This realization seared the very texture of this moment into her memory to accompany her on the journey to come.

In the dim gray of pre-dawn, a door on the opposite side of the courtyard squeaked open, and two more red-coated jailers emerged. They were gripping a heavily-manacled young man who moved woodenly, staring straight ahead.

The woman screamed, “No! Not you, Tommy! Not you, too! Oh, surely they can’t blame you!”

The male prisoner blinked several times before slowly turning his shoulders to recognize the woman who had so suddenly and violently come to life. “It’s all right, sister. It’s all right,” he murmured in a poor attempt at a soothing voice. “Don’t fear for me, I…” But tears rushed to his eyes and he fell silent. Before his mouth could again form words, the jailers themselves flinched in startled unison, as her lone female voice let out a long, shrill scream of utter agony, which was cut short as suddenly as it had begun. An officer had stepped up and punched the woman in the solar plexus, knocking the wind out of her, leaving her a gasping, writhing wretch, held up only by her flanking guards. He bent down, placing his face inches from hers, allowing one corner of his lip to curl in amusement.

“Next stop, my dear, is Execution Rock! And we will make the trip in silence, by God!” Then, addressing her escort, he commanded, “Let go of her!” Her jailers stepped away, letting her fall gasping in a heap to the cobblestones of the courtyard. While she fought for air, a quick picture of the trip to come flashed through her mind.

Execution Rock was where the British army executed prisoners, of whom they wished to make a public example. A mere pile of rocks at the western edge of Long Island Sound, it stood a mile offshore from any land, but just a quick row by longboat from the military garrison at King’s Point. Shackles were affixed to the sloping rocks between the high and low tide levels. The condemned were fettered hand and foot in a spread-eagled position at low tide and then left to contemplate their fate during the ensuing hours, knowing that, ultimately, they were doomed to a slow death by incremental drowning. Today was the day set by the judge for her to be taken there. Her dream had been only a dream, yes, but it was about to come true.

At this moment, a window opened out into the dim mist, from the second floor, overlooking the courtyard. From this window, a voice boomed, “Lieutenant! Bring her to me!”

Still gasping for air, knees bent, lying on her side in the fetal position, she was hoisted by her guards and dragged up the wooden stairway, through a door and before their commanding officer. At a nod of his head, she was dumped on the rough planking of his floor. He stood over her, saying “Release her bonds, and leave us.”

Captain Alexander Hendry stood silently, a grim smile on his lips, staring down at her limp form. When her breathing began to stabilize, she spoke.

“Oh, sir, why, sir? Why has my brother been condemned to the same fate as myself?”

Her question was met with silence.

“He is only a boy, of sixteen, surely he cannot be held responsible!”

The silence continued.

“It was I who brought him into the fort with me – under false pretenses. He had no idea that I was mapping your armaments! He merely came with me, as he did every week, when we sold our milk and vegetables to the soldiers. That is all! On my mother’s grave, sir, that is all! With God as my witness, that is all!”

Still, silence prevailed. Now her voice rose nearly to a scream, “It was me! Me! Only me!”

Finally, Captain Hendry broke his silence, “Then you will have only yourself to blame for his death, my dear. Let his blood be on your head.”

“But, sir, is there no decency, does the Crown not know mercy for…”

“Unless,” he continued, as if he had never been interrupted, “hmmm, I wonder?”

She merely stared as he continued, rubbing his chin thoughtfully.

“Perhaps there is a way.”

“What, sir, oh, pray tell me, what?”

“Perhaps a gesture of good faith on your part might induce me to find some way to ‘lose his paperwork’. Something might be arranged. It would not be unprecedented.”

“What?” The glare she threw his way demanded that he identify the gesture.

“Excuse me?”

“What would be a gesture of good faith?”

“Well, let me see. Oh, perhaps not. It is, after all, a foolish idea.”

“Tell me!” Then more desperately, “Please.”

“Ah, perhaps I spoke too hastily”

“Captain!” The officer of the guard was calling up from the courtyard.

Captain Hendry, annoyance clearly seizing him, strolled to the open window. “Yes, Lieutenant?”

“Sir, we need to be off shortly, if we are to carry out the sentence as directed.”

“Yes, yes, Lieutenant, just a moment.”

Swiveling on his heel, he addressed the woman, “As I said, perhaps I spoke too…”

“Anything! Please! Tell me! Kill me, but spare my brother! I’ll do anything you want.”

“Anything? How intriguing.”

Captain Alexander Hendry did not consider himself an evil man. He was, after all, a loving husband and a devoted father. But he had been stationed in what he considered a barbaric slum of a colonial city for three years now, and a man could only stand so much isolation and deprivation without a little amusement.

“You are a virgin?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Hmmm.” He rocked backward and forward on his heels, hands clasped behind his back, head raised as if in contemplation of the ceiling. He had to admit to himself that he would not have considered these games he so enjoyed with his prisoners, if the prison had been Newgate, or any other back home. But here, with these uncivilized brutes, and no one to share his bed for these long years, it was different. Now at least he had this – this little diversion.

“Please, sir, just tell me what to do to save my brother. He’s my father’s only son. He needs him to run the farm.”

“Oh, shut up!” These lying fools, always thought they could play on your sympathies, when in truth you could hardly believe a word they said. And they were stupid in the bargain. Truly, this was a dismal post. An exile. Still, it had its moments.

“Stand up.” It was days such as this that made his lot bearable. “Remove your coat.”

He approached, as she obeyed his order, looking at the floor, letting her cloak fall. He reached out his hand and pulled at the corner of her blouse, exposing a shoulder. Then he repeated the motion on the other side. She never flinched.

“I will give you a day and a night.”

“Sir?”

“I will give you a day and a night, in which to demonstrate to me your gratitude for my reconsideration.”

He reached out and placed his first two fingers under her chin, raising it, until her eyes met his. “If at the end of that period I am convinced of your gratitude, I shall set you both free. It will be put down to a bureaucratic mix-up. It certainly will not be the first.”

She stared silently, barely breathing, never moving. She feared that even the movement of her lungs might be enough to break the mood of the moment, in which he had thrown her this barest of lifelines. Blood pounding in her temples to a rhythm, driven by her heartbeat, seemed to shut out all other sound. He waited for some response. And as his adrenaline coursed through his body, he congratulated himself on crafting such an effective relief of the crushing boredom that filled his colonial tour of duty in New York. No matter what happened now, today would not be merely another day of tedium.

“Well, my dear? You heard the Lieutenant. It is time.”

Her eyes never left his, but they did change. The slightest film of moisture spread across them, and they narrowed, almost imperceptibly. Yet they did not blink, and they did not look away. Without diverting her gaze from her captor’s, she silently reached her right hand to her left shoulder and began to pull her blouse further down her body. He crooked his index finger, gently rubbing the underside of her chin in a light caress. Then his hand fell, and he returned to the window.

“Lieutenant! I must see you! A slight change of plan.”

Captain Alexander Hendry, His Majesty’s Warden of the military prison at King’s Point, New York, stepped out onto the crude wooden stairway, closing the door behind him. From where the woman stood, a slight hum of voices could be heard, and then the Captain returned.

“Very well! Please, my dear, don’t let me stop you.”

Hendry leaned back on his desk, as the pile of clothing at the woman’s feet grew. At length, he smiled broadly and began to circle her with the same authoritative air that seemed integral to his nature. Hands behind his back, he murmured approval as he considered his prize, inspecting her with a mounting excitement. Finally, in one practiced motion, he picked up the naked woman, threw her over his shoulder and walked into the adjoining bedroom, kicking the door closed behind him.

“May I take your cloak, Mr. Arnold, we’ve been expecting you,” offered Thomas Clark, secretary to the Massachusetts Committee of Safety. “The committee is in closed session just now, Mr. Arnold, but…”

“Squire Arnold, if you please,” reprimanded the visitor.

“Ah, yes, Squire Arnold, of course.” A short silence ensued. “If you will step inside, perhaps Mr. Nichols can offer you something to take the chill from your bones. It is truly a frightful night to be making such a long ride.”

Arnold gazed levelly at the secretary, and in a calm measured fashion that was his personal style, replied, “I do not need spirits to cloud my mind before I have a chance to speak it, sir.”

Coloring slightly, but deferring to the well-known, older man, Clark retorted, “Perhaps a hot cider to warm you, sir.”

Benedict Arnold turned slowly on his heel and snapped, “Just let me know, when the committee is ready to see me.” And with hands clasped firmly behind his back, he began to pace.

The uneven floorboards of Nichol’s Tavern usually produced some unsteadiness of gait in those, who were new to them. The thick planks of local, soft white pine had worn down under decades of boot traffic – everywhere but at the knots. The knots stood well above the rest of each board, and their appearance here and there at random intervals produced the overall appearance of a choppy sea. Unconsciously, Benedict Arnold slipped into the slightly bowlegged, rolling gait, with which he strode the decks of his ships. Others may have moved unsteadily on this floor, but Arnold never even noticed it.

As he was famous for doing on the forecastle of his trading sloop, Arnold paced back and forth impatiently. It was clear that this was a man who was used to action, resenting any constraints on his time. These characteristics had made Arnold a huge financial success, but had brought him few friends. Early in life, a yellow fever epidemic in his hometown of New London had carried away his mother and four siblings, leaving only Benedict, his sister Hannah, and a disabled, alcoholic father.

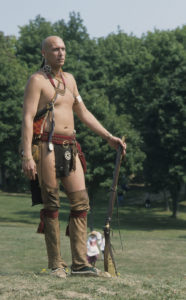

The town fathers saw that the boy was apprenticed to and adopted by an apothecary in the modest port of New Haven, where he grew up in a near-frontier environment, showing an early distaste for learning. While the other town boys were packed into the schoolhouse, studying their lessons, young Benedict was more likely to be found doing perfect swan dives off the yardarms of docked ships with the Indian boys, who still lived with their families at the edge of town and were his best friends. They looked at his aquiline nose and swarthy skin and gave him a name, which would one day seem so appropriate to his fate: Dark Eagle. He learned many of their ways and developed a reputation throughout the town as a wild boy – a boy, with whom mothers forbade their sons to play.

When business faltered for Benedict’s adoptive father, the grateful younger man felt it his obligation to throw himself into the family commerce. He shrewdly expanded the types of merchandise sold at the apothecary shop and gradually – through years of hard work – returned the family to a comfortable income and a position of respect. His five feet seven inches of powerful build and erect carriage looked taller, as he strode purposefully through the streets of a town that he felt had once looked down upon him as a poor orphan. Black hair and a sun-darkened complexion accentuated light blue eyes that fairly sparkled with intelligence.

Soon being the best merchant in New Haven was not enough. For kindled within the soul of this most unusual young man there burned a new fire – that of pride. The poor orphan child had grown into a man, bent on proving that it was he, not they, who was the superior human being. For years, the young merchant Arnold had complained bitterly about what he said were exorbitant prices of the goods he purchased for resale. He came to despise the wholesalers who seemed to do nothing but take the goods and mark them up.

In a style, which was to become associated with him for life, Benedict Arnold decided to do something about this. Using his savings and a small loan from the local bank, he bought his first merchant ship, a small coastal sloop, with which he began to make regular runs to the Caribbean. Carrying timber south, and rum, molasses, and other sundries back north, Arnold used the weeks at sea to train his men. By the time they reached San Juan or other ports, most captains and crew were ready for some rest and relaxation, even celebration. Not Benedict. He was in a hurry.

The greatest profits in trading went to the first captain to sail into port with goods, which had become scarce. Subsequent arrivals might only command half the price of the first ship. In the 1750’s, so many ships were lost at sea that the merchants of a port never knew whether the first Captain to sail in with this year’s crop might also be the last. The merchants were eager to pay top dollar, and an aggressive captain could literally sell his goods at the dock before they had even been unloaded.

Sea-going custom, however, demanded that when American ships dropped anchor in Caribbean harbors, captains would hail the new arrival and invite their commander to dine. The captains of other ships which lay in port would also attend. Much drinking and story-telling would continue far into the night. Meanwhile, the sailors of their vessels met in the port taverns, joining in celebration of surviving yet another dangerous passage. This was the ancient brotherhood of the sea.

The hangover the day after the festivities, however, invariably carried the price tag for such revelry – a lost day’s work. Still, no one had ever thought of tinkering with this tradition, until Arnold. He tried denying his crews port liberty, but quickly changed his mind, when he discovered that continuing such a policy would make it impossible for him to get crews at all. Instead, Arnold himself stayed aboard the ship to supervise and assist with the dock men’s loading and unloading. He did not entertain his fellow captains. He did not accept invitations to be entertained. Benedict Arnold was a businessman, driven to attain a station in life better than that, to which he had been born. He was glad that he didn’t live in class-conscious England, which made such upward mobility well-nigh impossible. Other captains, however, understood none of this, and took his aloofness for arrogance. One even challenged him to a duel over his refusal of an invitation. When the challenger’s first shot missed, but Arnold’s creased his arm, the steady blue eyes of Benedict looked straight at his opponent, who was reloading, informing him, “If you miss again, I shall shoot you dead.” At that point, the challenger announced that satisfaction had been obtained.

There was much talk and much resentment, but all of it was tinged with a touch of envy, because month after month, year after year, Arnold carried more cargo and obtained higher prices than any other captain on the Caribbean run. He quickly went from being the most prosperous shopkeeper in New Haven to its most profitable sea captain as well.

Now, on this wet and bracing spring evening in 1775, Arnold had come to Nichols’ tavern with a plan. He turned on his host and snapped, “How long are they going to be in there?”

“Excuse me, Squire?”

“How long are these damn intellectuals going to keep wagging their tongues?”

“I really wouldn’t know, Squire.”

“Well, I was told to report here this evening and, by God, I am here, and I am here for a reason. Would you please tell them I would like to get on with it.”

He went back to pacing, hands still clasped behind him. Finally, approaching midnight, the Committee door opened. Clark entered, closing the door behind him. Then, a few moments later, he emerged – summoning Arnold with a beckoning hand. “If you will, sir, the Committee shall see you now.”

Benedict Arnold strode across the threshold, and all eyes looked up. This was a man who made an entrance. It was rarely a conscious attempt; it was simply the physics of personality. Even here in the dim candlelight, under a low, beamed ceiling, there was an indefinable aura about him.

“Won’t you please be seated, Squire Arnold.?”

Arnold looked around the long table appraisingly. From Silas Deane of Connecticut, he got a familiar nod. The others simply returned his gaze levelly. There was no hostility. Neither was there friendliness at this table. There was simply a circle of hard-working and dedicated patriots who were deep into a long night of business.

Tentatively, Arnold ran his tongue over his lips and began to speak. “Gentlemen, I come here tonight as a friend of independence. Silas Deane will confirm that.” Deane nodded. “For some years now, myself and other traders in New England have risked life and limb to eke out a livelihood with backbreaking labor and the high risks of the sea. Now Old John Bull seems to have decided that any profits we make belong to him. His taxes, his duties, his regulations on import and export have crippled us. We have a right to reward ourselves for our hard work and our risks. We are not slaves, and neither are we indentured servants, nor children. Yet the Crown insists on treating us as such. And I for one, Gentlemen, have suffered insult enough.”

No one interrupted, so Arnold continued. “There has been much talk, notably in the fine pamphlets of Thomas Paine. Stirring speeches by Patrick Henry and others. But, Gentlemen, the time for speeches has passed! Let us take the ideal and turn it into reality!”

“And how do you propose to do this, Squire?” drawled John Adams in a clearly skeptical tone.

Arnold turned his gaze on Adams, coloring visibly. His jaw set, he responded in a less than level tone. “By the same means that kings are always stopped, sir. Muskets and cannon fire!”

“All very good, Squire. But of muskets we have few, and of cannon, next to none.”

“Precisely!” Arnold retorted, and at this the room grew still. Arnold was clearly a man with a temper. The Committee was tired. And while they were not intimidated, no one wanted a fight. Arnold sensed this, and allowed the silence to continue for several moments – producing just the kind of tension-filled moment he desired. Finally, he spoke, “That, gentlemen, is why I am here.”

“Go on, Squire,” said Samuel Adams.

“Gentlemen, we have thirteen colonies, filled with farmers — barely one in twelve owns a musket, and virtually none has ever faced hostile cannon fire. Revolt against the English army without cannon of our own is sure suicide.” Around the table, heads nodded curtly in recognition of this bitter truth. A candle on the table begin to sputter, casting a pulsing shadow of Arnold on the plaster wall behind him, as he continued. “What I propose, Gentlemen, is to obtain a complement of cannon.”

Heads now stopped moving, and hands stopped writing. He clearly had their attention. “Once they realize that Lexington and Concord were not an aberration, the English army will go on full alert. It will guard its arms and ammunition with a vigilance, which will make any attempt at gaining them well-nigh impossible. Therefore, we must strike before making a full declaration of our intentions.”

No response came from the eleven men.

“We must strike first and declare our independence later. We must raise our arms from British stores.”

“And just where, Squire, do you intend to walk in and ‘raise’ a complement of cannon?” Dr. Joseph Warren was doing the interrogating now, looking skeptical.

Arnold, now hitting his stride, stood close by John Adams, towering over the diminutive man, and uttered a single word, “Ticonderoga.”

“Gentlemen,” interrupted Samuel Adams, “Let us have some refreshments before we continue in our discussion. Mr. Clark, drinks for everyone, if you please.”

Arnold was puzzled. Clearly, they had sat up and paid attention to him. But now, surely, they were choosing to stop him with an utterly trivial diversion. When Clark asked Arnold what he could get him, “Water” was the response. As Clark continued around the table taking orders, Arnold began to notice sideways glances and conspiratorial nods being subtly exchanged between the Committee members. Slight jerks of the head were obviously freighted with meaning. There was an entire silent conversation taking place here that Arnold could not follow. There was a level to these men’s discussions that he had not expected.

When Clark had returned with refreshments and everyone had been served, Samuel Adams spoke up, “Excuse the interruption. Pray continue, Squire.”

Slightly unsure of himself for the first time this night, Arnold cleared his throat and resumed. “Fort Ticonderoga, in the Hudson Valley, below Lake Champlain, has two types of strategic value for our cause. In the first place, it controls the key waterway connecting the Hudson Valley to the St. Lawrence and Canada. These bodies of water allow the English to use their overwhelming superiority in naval power to reinforce and re-supply their troops. If they control the Hudson Valley, they split the colonies in two. They can then attack New England and the South one at a time, in any fashion they please. You all know, that even as a united front, the odds of our success are not high. Divided, we most certainly shall fail.”

Arnold now paused again for effect, and noticed that this time the silence seemed to be tinged with an excitement, which was not there when he had first entered.

“Currently, Fort Ticonderoga is occupied by a mere skeleton garrison. My scouts have informed me that they are not on alert and, in fact, they apparently feel so secure that no one has paid attention to the wooden gates. They have warped over the years and would probably prove impossible to close and lock. They are left open all the time. A waterborne assault on the fortress is impossible. Large stone walls and most of the cannon face the lake.”

John Hancock interrupted, “And the last land assault, in 1758, cost the attackers 2,000 dead, before they gave up and withdrew.”

“I believe that a small force, moving quietly through the forest on foot, could reach the fort by stealth and rush the gate. If such a force were composed of a few good men, they could quickly overwhelm the garrison.”

“Go on, Squire.”

“At this point, we could hold the fort as our own defensive jewel, breaking the British control over the Hudson Valley. But more importantly, I fully believe that the fort can be held with a third of the cannon there now. The rest could be mounted on wheels and hauled to Boston where they could be turned on the redcoats with some effect.”

“And where, Squire, did you ever come up with such a wild plan?” prodded John Adams.

Arnold colored yet again, fought vigorously to control himself, and through gritted teeth muttered, “It’s obvious, isn’t it?”

“If it is obvious, Squire, why has no one done it?”

“That, gentlemen, is for you to answer.”

“Or perhaps the Continental Congress. They have forbidden such attacks.”

John Adams looked across to Silas Deane. These two had been exchanging significant looks ever since the break. Deane nodded once to Adams, then gestured toward the door with his head. Adams returned the nod and spoke, “Thank you, Squire, and what is it you request of us?”

“Merely permission to lead such a force.”

“And do you expect us to supply this force?”

“No, I have men well-armed and loyal to me. Several of them are at the fort now. They have been scouting the defenses for a month.”

“All right. If you will step outside and leave us for a moment, Squire, we will discuss your proposal and let you know our answer.”

Clark coughed diplomatically to draw Arnold’s attention to the door, which he had opened for him. As Arnold left, Adams’ glare gradually evolved into a broad grin – which John Hancock returned. Then, still smiling, John Adams spoke. “Well, I guess it truly is obvious.”

“And what do you mean by that, John.?”

“Simply that Arnold is right. We must attack Ticonderoga without warning to gain cannon. And to gain a strategic position in the Hudson Valley. Congress be damned! And how could Arnold know that Ethan Allen was here with the exact same plan a month ago?”

Chuckles all around the table.

“Silas, you know Arnold. What kind of man is he?”

Silas Deane settled uneasily back in his chair. He thought for a few moments, then began cautiously, “He is a man not easily summed up in words, gentlemen. He’s a successful merchant, with an exceptionally beautiful wife who is devoted to him, three young sons, and a mansion that dominates the New Haven waterfront. He is a natural leader, a man who is used to command and eager for action. He has a reputation for being hard-driving and not very likable.”

“Well,” Sam Adams sighed, “We have had a surplus of ‘likable’ men for some time now. We could stand to redress the balance, by adding some unlikable men of action.”

A single “Hear, hear,” and several approving grunts made it clear that Benedict Arnold had achieved his goal.

“But Ethan Allen is already on the march. His Green Mountain boys will be at Ticonderoga any day now.”

“Yes, that’s true. But it was a good plan when Allen presented it, and it is a good plan now. That, as you recall, is the only reason we gave the commission to Allen.”

“That’s true,” interjected John Hancock. “I don’t trust that Allen. He’s only interested in building empires for himself. He wants to declare Vermont a separate kingdom with himself as king. That is all that interests Ethan Allen – not our cause.”

“Yes, yes. We discussed all this a month ago. But we do need cannon, and we need Ticonderoga. Furthermore, we need someone with the means, the fortitude, and the brains to take it.”

“Brains? Ethan Allen?”

“All right. All right. Your point is well taken. I think Arnold might just be the man with the brains.”

“Well, we can’t just call it off with Allen and give the commission to Arnold. Allen will do it anyway and just keep the cannon! Don’t forget, he is the one with men on the scene now.”

“I know, I know. Isn’t there some way we can use Arnold to keep Allen in check?”

Secretary Thomas Clark cleared his throat. “Yes, Mr. Clark?”

“Excuse me, sir, but perhaps a joint command might be the answer.”

Sam Adams laughed heartily. “Why, Thomas, you devil!” He laughed again. “You have learned from your time with us, haven’t you? Please, elaborate.”

“Well, sir, from what I have heard here tonight, both these men have dangerous egos and may go their own way, following their own, quite independent plans. Forcing them to share the command, on an equal basis, assures us that each will keep the other in line.”

“What say you, gentlemen?” Adams prompted.

Nods of assent all around.

“We shall put it to a vote then. All in favor?”

“Aye.”

“Opposed?”

“Nay!” Silas Deane, the only person at the table who knew Arnold, was the only person at the table to vote against him.

“Silas,” flustered John Adams, “You puzzle me sometimes. First you speak well of Arnold as a man of action, then you vote against him!”

“It is not his ability to act or to lead that concerns me, sir. It is his ability to belong as a member of a group, striving toward the greater good – a common goal. Arnold cares too much about Arnold. I worry over his ability to obey orders, to sacrifice his own good for the good of the whole.”

Adams fumed, “Let us worry about that later, sir, shall we! For the time being we need cannon!”

“Thomas, bring in Mr. Arnold.”

To Jemmy, Harner’s Notch represented everything to which she and her husband had dedicated their lives. When the two had first eloped – a full generation before, she reminded herself – they knew that they would have to head for the frontier to escape the wrath of her father. ‘Landed gentry’ was what they called his sort: a wealthy tobacco farmer with a 2,000-acre plantation and the slaves to work it. Those slaves who had tried escaping had always been hunted down and brought back to horrifying punishment. Certainly, his agents would range far and wide to bring back his only daughter from the clutches of the penniless farm boy, with whom she had fallen hopelessly in love. So, to the wilderness they went.

The eighteen-year-old ax-swinger and his sixteen-year-old bride had reached the settlement of Madison in their headlong flight at about the time, when their money ran out. The ‘downtown’ part of Madison consisted of six log cabins and a mill. Its other forty inhabitants were spread over several mountains. Henry and Jemmy had found a hillside and valley that was unclaimed, inside which you could not even see your neighbor’s chimney smoke.

It was Henry’s abilities with an ax that had provided their first home – just in time for winter. It was his skills with the long rifle that had kept them fed that first year. Henry may have grown up on a farm near the coast, but he was as good as any mountain woodsman with the ‘Pennsylvania rifle’. These six-foot-long flintlock muskets added something new to the industry of firearms. They possessed rifling. This meant that inside the barrel there were grooves which curved in a lazy kind of spiral. Any musket ball that passed through such a barrel was given a spin by these grooves, or ‘rifling’. This spin kept the projectile on target, and made certain muskets, crafted in Pennsylvania, some of the first true rifles, and the envy of the military world (or so Henry said). Normal muskets had a fifty percent chance of hitting a deer at fifty yards. Henry could put a ball in its head at 100 yards – every time. At 200 yards, he could hit a man on the run.

It was no surprise then, that when western Virginia Indian tribes went on the war path, it was Henry to whom the neighbors turned. Of course, every man had taken up arms and had done his part. But Henry had used all his hunting skills to locate the war party, shimmy up a tree, and put a ball in the head of the chief, before the braves had even geared up for the attack. This apparently convinced the war party to try another community.

It also brought him to the attention of a living legend: Dan Morgan. Henry’s hand-picked group of long rifles had done something never before accomplished in the mountains of Virginia Colony. They had taken the offensive against their Native American neighbors. Penetrating deep into the heart of unsettled wilderness, the ragtag bunch in buckskins had brought their hunting skills and marksmanship together in a group, which soon distinguished itself for bravery and effectiveness. War parties never bothered their valleys again.

This had made Henry Warner something of a local hero. It provided a commodity, which no amount of money seemed to do here on the frontier: It had provided respect. Since then, his sons had helped him clear a large and prosperous farm. They had grown, married, and gone off to homestead land of their own. Jemima and he had everything they needed.

When Henry had left their cabin to go with Dan Morgan, he was a driven, but insecure young man. He returned four months later with a relaxed, confident air of authority that, at first, unsettled Jemmy. She told herself that this was not the personality of the boy she had fallen in love with. With time, though, she realized that this impressive ‘new man’, who had come back from the wilderness after defending his loved ones, actually prized her above all else in life. Henry directed all of his new-found skills into protecting Jemmy and their world. And as he did so, Jemmy grew to revel in the new Henry. He made her feel warm and safe, loved and protected. He made her feel like a woman. One of the luckiest women alive. Now that their children were grown and had moved on, they were growing even closer, and the valley seemed quieter than ever.

Husband and wife both still sported the black hair they had begun with, but time had put new lines on their faces. Henry was as lean and muscular as the day they had met, though with a bushy beard that had come along later. Jemmy had plumped up with each of her pregnancies, but her ceaseless motion had always slimmed her right back down, and she blushed with pride whenever a quick turn caught Henry leering at her backside. They were considered a handsome couple, just now learning to enjoy an occasional day of relaxation like this.

It was, therefore, all the more jarring when she heard a knock on the front door. She startled. Normally, she heard someone approaching, long before they got close enough to knock. Only Indians moved this quietly, and stealthy visits from them were not something to be relished. Without pausing to look, she hurried out the back door to the barn for Henry. He was bent over the milk cow that had of late produced more in the way of lowing complaints than of milk. He turned at the sound of her footsteps on the straw.

“Henry! There’s someone at the door!”

He laughed. “Who?”

“I don’t know. I never heard their approach. That scared me enough so as I came straight out here.”

At first, Henry Warner smiled. Then he paused, cocking his head, froze for several seconds, then swiveling fast to pick up his rifle. He cocked the flintlock and was rising from his milking stool, weapon in hand, when a human shout shattered the mountain calm.

“Henry, you old bastard, where are you?”

Henry froze, holding his breath. The speaker seemed to be on the far side of the house. It took a few seconds to place the voice.

“Dan?” he yelled back.

“No, it’s the sheriff, come to tell you you’s never were legally married after all, and I have a warrant for the arrest of you, Jemmy, and your children!”

Henry and Jemima looked at one another, laughing.

“And what makes you think you are man enough to take me?” Henry bellowed back.

Only silence followed.

“Dan?”

“Dan?” he repeated.

“Because,” a voice suddenly very close whispered, startling the couple, “I’ll be right on top of you before you know what hit you. Like always.” And with that, a giant of a man stepped into the barn behind them, grinning from ear to ear.

Four hours later, sitting at the Warners’ table, Morgan’s grin was gone. He and Henry had been laughing and drinking, recalling old times. War stories with war comrades were a tradition best left undisturbed, Jemmy had learned. So, in the past, she had largely left them alone. She had fed them and refilled their glasses, even laughing with them on occasion. But today she was not smiling.

“I need you, Henry,” Dan Morgan continued. “The men respect you. They know you are the best at what you do, but that you don’t volunteer for no suicide missions. They’ll figure, that if you’re coming, then this must be all right. And that’s what I’m counting on. I’m counting on you, Henry.”

“Go count on someone else!” she snapped.

“Now, Jemmy…” Henry began.

“Dan, you’ll kill him!” She was practically screaming.

“But, Jemmy…” Morgan began to defend himself.

“Henry is not what he used to be, Dan! He’s had the consumption and is in no condition to go back to chasing Indians.”

“But I ain’t aiming to chase Indians,” the amiable giant replied with a smile.

The Warners stared at him, puzzled. Dan Morgan was a living legend. In an era, when the average man stood five feet six inches, Morgan was closer to six feet four or five inches. An unruly shock of dark hair always seemed to be hanging over his high forehead. His rugged good looks were only marred by a splash-shaped scar on his left cheek, where an Indian musket ball had exited after entering the back of his neck, taking out all the teeth on that side. Barrel-chested, a champion arm wrestler, expert hunter, and superb marksman, Morgan carried what people called ‘a presence’. Everyone on the frontier knew that he had once taken 500 lashes from an arrogant English lieutenant, without uttering a sound. His skill at tall tales, that most respected of American backwoods pastimes, was as legendary as his ability to lead men into battle. Morgan had proved himself time and again in the French and Indian War.

“When a man like that stands up with a rifle in one hand and a tomahawk in the other and gives a war cry, followed by a smirk,” Henry once told Jemima, “and then plunges toward the enemy without so much as a glance back, you actually want to follow him – even when you know he’s heading toward a force that outnumbers you. It’s like you just know he is going to win somehow, and you’re afraid to be left out.” But in Henry’s case, Jemima knew, the tie ran even deeper.

At the battle of Edward’s Fort, Henry had been kneeling, struggling to reload and, while his ramrod was still in his rifle, three braves burst out of a ravine just a few steps from him, tomahawks raised. Henry was sure he was dead. But instantly, seemingly out of nowhere, Morgan had leapt between the braves and the kneeling Warner. “He had a tomahawk in one hand and a scalp in the other,” Henry told her, “and he held them out, and the braves actually stopped. Dan had this grin on his face that I think they just couldn’t understand. Then he waved the scalp at them, and that kind of got them going. It was fresh, still dripping blood. Those fellers got plenty mad and lunged at Dan. I’m still not sure exactly what happened, it all went by so fast. But best as I can recollect, Dan sidestepped the one on the right and hit the middle one an uppercut with his tomahawk. Then he threw himself in the face of the third one, and they wrassled to the ground. By now, the first one had stopped and turned and was coming at Dan from his blind side. My ramrod was still in my rifle, but it was loaded, so I just aimed and pulled the trigger. The ramrod went halfway through that injun’s neck and then just stopped, half of it sticking out one side of his neck, half out the other. He turned and looked at me kind of funny, raised his tomahawk, and then just crumpled to the ground. By the time I was able to turn and locate Dan, he was getting up from the ground with another scalp in his hand, and he was smiling away like he was at a party or something. Other than the scalping, there wasn’t a mark on that corpse, but his neck was bent at a funny angle. If Dan hadn’t been there that day, Jemmy, I wouldn’t be here today.”

So, when Dan Morgan spoke, the Warners listened.

“No, this time, Henry, I won’t be chasing Indians. No Indians what hide on you and are hard to see. This time I’m chasing a bunch what is polite enough to wear red, so as you can see them real good through the trees. They stand real straight so you can get off a fine shot. And just in case your aim is a little off, they are considerate enough to stand in lines. If you miss one, you get the man next to him. It’s like shooting into a small pond with a large flock of ducks. Interested, Henry?”

“What in the world are you taking about, Dan?”

“I’m talking about freedom, Henry.”

Though Robert reveled in the scent of the sea today, at other times it made him so sick to his stomach that he wished he would die. This was when he would wake from a deep sleep on one of his father’s six trading sloops and rediscover that the force of nature behind that smell wreaked havoc with his insides. Born the third son in a family of sea captains, importers, and coastal traders, he soon found out that he simply couldn’t stomach the sea. His father had insisted that he go out again and again, once as far as the Caribbean, but he had never developed sea legs. As a result, he remained something of an embarrassment to the elder Townsend.

Yet Robert never minded days like these, when the sea breeze served merely as another sensual pleasure in ‘his’ garden nook behind the dark green hedges surrounding the Townsend residence. Called Old Homestead, it was a stately house, by rural colonial standards. The sounds of seagulls and songbirds dominated. Only occasional hoof beats intruded from the dirt street of this hamlet of several dozen wood frame houses along the southern shoreline of Long Island Sound. Here in the garden is where he tried to spend the bulk of his time in warm weather, and today was no exception.

Within an hour of his arrival, an onlooker would have found Robert Townsend seemingly dozing in a hammock (the one shipboard custom he had enthusiastically embraced). An open volume of Pope covered his face, and one arm dangled idly. When the volume was lifted for as long as it took to read another poem, the face that emerged was that of a handsome twenty-two-year-old with a thick mane of long black hair, worn tied back, emphasizing the piercing pair of light blue eyes below. Combined with an aquiline nose and strong cheekbones and jaw, the total effect was distinctive: His was a face that stood out in a crowd. Only medium height, his trim physique made him look taller than he was.

When the poem was finished and the book replaced over his face, he would again seem to all the world to be asleep. In reality, he was engaging in his favorite pastime. While his mind still reverberated to the verse of the greatest poet in the English Empire (in his own humble but educated opinion), his ears took in every rustle of leaf, hum of fir, birdcall, and bee, as well as the occasional cries of his seven-year-old sister Phebe. His nose delighted in the pungent perfume of his father’s English boxwood, imported from the mother country and nurtured along by the gardener into a precarious coexistence with the American climate. His hands, languidly dangling off the hammock, served as secret detectors of the deliciously cooling gusts of wind.

His senses were bathed in a sort of luxurious stupor, but this was a familiar game he played with himself. After the pleasure of Pope, he engaged in a form of sensory overload. Only when his senses of smell, touch, and hearing were full to overflowing would he reach up and slowly remove the book of poetry that was blocking his vision. Keeping his eyes open while he did this always reminded him of watching the curtain go up on a play. All at once, his already stimulated senses would be driven over the top, as darkness yielded to brilliance, and perhaps the occasional cumulous cloud drifted lazily overhead, its brilliant white contrasting with the dazzling depth of blue, overlaying all. For Robert Townsend, this was as good as life got.

“Robert!” An authoritative male voice shattered the castle of carefully constructed sensual bliss.

“Robert! Where are you?” Townsend let out a long sigh. By the edge of excitement in his father’s voice, he knew that the reverie was over, probably about to be replaced by a long, boring monologue on something he would rather ignore.

“Robert!” Oh, well, the son thought, it seems inevitable.

“Here, Father,” he finally muttered in an annoyed tone, barely audible over the rustling trees.

“Well, why the devil didn’t you answer at once? Oh, I see, Pope again, is it? Robert, my God, the world is on fire, and you seem content to just lie here in a hammock, reading Pope!”

“Someone has to do it, Father. Colonies without culture would hardly be worth saving, now, would they?”

“Well, come along, son, it’s time for supper. Mr. Woodhull is dining with us tonight.”

Robert sighed, took one long last gaze at the incomparable sky and headed inside. “Good day, Mr. Woodhull, so good to have you here again.”

The tall, painfully thin man extended a hand. “Thank you, Robert. And what are you up to these days?”

“Well, I…”

“The usual!” his father Samuel interrupted. “Reading poetry!”

“How pleasant,” Woodhull responded, with a tone of careful neutrality in his voice. He knew the family well enough to realize what was coming.

“My God, Woodhull, brave men are fighting and dying at Lexington and Concord, while my son sits in a garden, reading poetry, and all you can say is ‘How pleasant’?”

Woodhull, wisely, chose silence.

Robert’s mother Sarah tried to restore peace, or at least provide a diversion. “Please, everyone, eat up before the food gets cold. We have some of those new-style beans in molasses from Boston here, boiled beef, some of the last of the potatoes, oh, and Robert, will you help Phebe with her bread?”

Everyone knew, though, that once Samuel Townsend had the fire aroused within, there was no stopping him. “All I’m saying is that it is time for all good men to choose sides. Do they stand for pride or submission, freedom or slavery? That’s the choice, and it doesn’t seem a very hard one to me.”

Robert hesitated but could not contain himself. “You’re wrong, Father. There is also the choice of what to do about it. You go on about the nobility of the men at Lexington and Concord. I don’t dispute that, Father, no one does. But nobility is measured for a gentleman in how it affects the lives of others, and whether a man’s actions do more harm than good.”

“What are you talking about, boy?”

“I am talking about the ramifications of such actions. After all, what did they really accomplish at Lexington and Concord?”

“What did they accomplish?” Mr. Townsend repeated in amazement. “Well, let’s see, they put us at war with Old John Bull! I guess that doesn’t compare with Mr. Pope’s latest volume of poems, in your estimation.”

“Father, I have said this to you before. Is it right to begin a war that cannot possibly be won? If this ‘rebellion’, as you call it, gets any further out of hand, there will be slaughter. And very few of those slaughtered will be British soldiers.”

Woodhull cocked his head, leaning across the table towards the young man, “You sound like a pessimist, Robert.”

“I prefer to consider myself a realist, Mr. Woodhull. No group anywhere in the world has ever beaten the army of the British Empire without cannon on its side.”

“You may have a point there,” Woodhull admitted.

“And exactly how many cannon factories do we have in America, Mr. Woodhull?”

Woodhull remained silent because he knew the answer – none.

Robert knew he had embarrassed their guest, but his normal gracious manners were swept aside under pent-up emotion. “St. Augustine said…”

“Oh, my God, now it is St. Augustine, is it?” his father cut in derisively.

Robert turned, glared at his father, and continued. “St. Augustine said that God condones a just war. But he states that one of the conditions of a just war is that it must be winnable. Otherwise everyone who dies, dies for nothing but pride. The prosecution of such a war is no better than murder, on both sides.”

He now swiveled back to Woodhull. “To revolt now is to create slaughter! How can you condone that?”

His mother cut in, “Robert, your manners!”

As he calmed himself and began to fumble an apology, his father burst out, “You, Robert, are beginning to sound more like a parson than my son!”

“A good point, Father. We are members of the Society of Friends. At meeting last Sunday, did not Reverend Silas remind us how our faith prohibits us from killing our fellow man?”

“William Penn was a Quaker, and that never stopped him from defending his land from the Pennsylvania tribes!”

“That does not make it right, Father. Penn was famous, certainly. But no one ever said he was holy. George Fox tells us that all that matters, is finding the Divine Light within each of us.”

“Oh, for God’s sake, boy!”

“Father! Now you are blaspheming on the Sabbath?”

“I left you with your mother too much, that’s what I did.”

This remark stung so deeply that Robert Townsend had to call up all his formidable powers of deception in order not to let his father see how emotionally injured he was by this belittling of his manhood. Nothing had ever meant more to him than his father’s approval and companionship, but his father had spent most of Robert’s childhood away at business at his store in the city, or on the decks of his trading schooners with his two older brothers. Robert had grown up with his mother as guide and his younger sister Sally for companionship. He finally decided that if his father didn’t have time for him, he would go his own way in life. And that way had involved books. What thrilled Robert was learning, culture, art, the play of the senses.

This bright, well-schooled young man of twenty-two had acquired a mastery of art and literature that he could share with no one in this sleepy port village. He had, accordingly, gone inwards. The life of the mind was what Robert valued. He yearned for companionship and a role in the outside world, but none presented themselves in Oyster Bay, or anywhere else he traveled on Long Island. He kept himself apart, quickly learning that it was better to hide his thoughts than to be called a sissy, an effete. When he spoke about the things he cared for, people seemed to think that he considered himself above them.

Robert’s mother Sarah had been right about one thing: He was sensitive. Since he was a child, he could tell what people thought – not by any magical power – but by picking up the nuances of how people held themselves, their tone of voice and choice of words when they spoke – even how their eyes, fingers, and feet moved. He discovered early that it was better not to talk about this. Voicing it only produced anger and denial in those he was observing. Most people did not enjoy admitting to what they really thought. So, Robert had gone through life acting. Only his sister Sally, seven years younger, really understood him.

Robert probably felt as warmly towards his father as any son. However, something in the father’s character kept him from expressing his own warmth to Robert in turn. The son could sense that it was there, but that his father had never known quite how to let it out. He met with his father, where the elder Townsend considered it safe – on the playing fields of intellect. No one in Oyster Bay had ever belittled the intelligence of either. These two thoroughly enjoyed the stimulation of one another’s conversation. Their arguments at the family dinner table were famous. Visiting Quaker parsons, ship’s captains, doctors, and schoolteachers all welcomed an invitation to the Townsend table.

Today, though, it was a table of distress for Robert, and his urge was to flee. “Will you excuse me, Mother? I believe I left a book outside, and it looks as if it might rain.”

An hour later, they were all sitting indolently in the garden, sipping lemonade and listening to a mockingbird. Only eight-year-old Phebe, rolling her hoop around the yard, displayed any energy. It was all the more alarming, therefore, when a rumble of hooves could be heard galloping up the street and clattering to a halt in front of their house. Samuel rushed inside and emerged a minute later beaming, practically pulling a young man after him, whom he continually clapped on the back.

“Go ahead, Thomas,” he laughed, “Tell them, tell them, what you told me!”

“We’ve taken Ticonderoga!”

Blank looks all around the garden prompted Samuel Townsend to explode, “Don’t tell me my own family doesn’t know what this means!! It means we won’t be colonies for long! Look at this dispatch from Albany. Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold have taken Fort Ticonderoga!”

“Ti what?”

“Benedict who?”

“Well, of all the – oh, what’s the point?” the elder Townsend’s voice trailed off, its decibel level dropping, as its tone of depression rose with his shoulders. “Do you really not know who they are? Robert, how about you?”

“Well…” Robert trailed out the word with an obvious air of disdain. “Isn’t Allen some wild frontier fellow, marauding about in the mountains up north somewhere with a band of hooligans?”

“They call themselves the Green Mountain Boys!”

“Yes, precisely. You see, Father, I do know something about him, but who was that other fellow?”

“Arnold, Benedict Arnold. Of New Haven.”

“No. Can’t say I’ve heard of him.”

“Well, while you have been lying here reading books, these two men have been risking their lives to give us our freedom!”

“What did they do?”

“They showed up in the middle of the night and stormed the gate of the great British fort above Albany. Took the sentries by surprise and captured it without firing a shot!”

Robert’s sole response was to blink as a patch of sunlight broke through the trees.

“Son, do you not realize the importance of this?”

“Well, Father, I guess you’re going to tell me it’s like Concord and Lexington. A great victory over the British armies.”

“Well, it is! Robert, this means we have cannon. Don’t you understand?”

Robert sat up, slowly swinging his tensed legs over the side of the hammock, squinting at his father through the afternoon sun.

His father continued. “Sam Adams and the others didn’t send Arnold and Allen after Fort Ticonderoga, because they thought it would be a great lark, or even a symbolic gesture. They did it, because Ticonderoga has masses of the one thing the American army does not have – cannon!”

“How many?”

“I’m not sure, hundreds, I think. Besides the powder and shot, not to mention muskets, bayonets.”

“It’s the cannon that count though, isn’t it, Father?”

“Yes, you know it is! Why, Robert, have you ever heard of anyone beating an English army without cannon?” and he winked.

Robert was wide awake now. “You say hundreds of cannon?”

“And the powder, and the shot. And the greatest strong point of the Hudson Valley, which is crucial, because…”

“The colonies cannot unite, while His Majesty’s armies control New York.”

“Ah, so you do understand something…”

“I may have been disinterested, Father, but I’m not deaf. I have heard everything you and your friends have spoken about. And I had decided your cause was doomed from the start.”

“And so, Robert, what do you think now of ‘our cause’?”

“I think, a few more victories such as this, and you may, perhaps, have a chance!”

The camp buzzed with talk of what they had done. Morgan’s hand-picked band of ninety-six volunteers, afraid that the action might be over before they got here, and eager to help out their Boston ‘neighbors’ in need, had covered an incredible 650 miles in three weeks. This meant walking over thirty miles a day for twenty-one straight days, on trails and bad roads. She knew that Henry had assumed she would crack, plead to go home, and relieve his embarrassment over having a ‘nursemaid’ along. It was obvious that most of the men had felt the same way. But day after day, as Jemmy fell in at roll call shortly before dawn, and then was still there at night, she noticed a gradual, but pronounced change in attitudes toward her.

In the beginning, some of the men had simply ignored her, clearly angered by the presence of a woman. Others had been overly solicitous – always trying to help her, doing small favors without being asked. All of them watched their language around her.

However, as Jemmy showed that she could hold up as well as any man under this blistering pace, a funny thing happened. They began not to notice her. Those who had liked her, actually stopped trying to help her out. Those who had hated her, forgot to ignore her when she said hello. She began to hear much saltier language from those, marching around her. All this she took for what it was – one of the greatest compliments ever paid to her. This extraordinary band of America’s best frontiersmen had begun to accept her as one of their own.

When they had arrived here at George Washington’s assembly center, it had taken less than an hour to run into the famous Green Mountain Boys of Vermont. Like Dan and Henry’s group, they were woodsmen in buckskin and moccasins, who were nearly as much Indian as white in their ways. “Men!” she said to herself. “Can’t they ever get along together?”

Here were two groups, who had more in common than anyone else in these colonial militias, and instead of celebrating their common bonds, it had taken all of five minutes to start a near brawl. First, the Vermonters started bragging about their conquest of Fort Ticonderoga. Then the Virginians shot back that it didn’t take much gumption or skill to sneak up on a sleeping Englishman, and how they’d done far better than that back in the French and Indian War, when they’d stolen into the camp of an Indian war party…

On and on it went, until they were set to start scrapping.

The friction with Allen’s men paled, however, to the boisterous, buckskin-clad riflemen’s effect on the tight-lipped Yankees of John Glover’s Marblehead mariners. These modest Gloucester sailors resented the loud boasting of the strangely dressed ‘foreigners’, and within a week, the exchanged insults led to blows. Half a dozen men on either side were swinging fists, but when Glover saw Morgan storm toward the group, hollering, he assumed that order was about to be restored. He had no way of knowing that a good bare-knuckled fistfight was Dan Morgan’s favorite form of recreation. Morgan waded in, swinging, and within seconds, two hundred men were locked in a furious brawl.

Much of the rest of the army came to watch and cheer on one side or the other. Most of the participants felt they were just getting warmed up, when George Washington galloped in, leaped off his horse, and battled his way to Morgan and Glover – beating them with the hilt of his sword to get their attention – demanding that they order their men to cease. Jemmy, disgusted by it all, turned away to wander the camp alone.

Passing one kettle after another, hung from iron tripods over cooking fires, she began to see that cookware was probably the only piece of equipment that most groups here had in common. The weapons were the widest array of muskets and fowling pieces she had seen in her entire life. The clothes were just as varied. Washington had a few regular army types in tight white breeches, blue coats of heavy wool, and black tri-cornered hats. They sweltered in the heat. But most of the men here, boys really, many of them, looked like they had started out to the post office one day to mail a letter and had just kept on walking. Since it was summer, most had simple linen shirts, white and blousey over-pants, which were already so torn and dirty that it was hard to tell what style they had once been. Some wore boots, some had silver buckled shoes, which had begun to disintegrate on the walk here. A few gentlemen had fancy uniforms tailor-made with braids, gold buttons, and cockeyed hats, sporting feathers, finished off with polished riding boots. Still others were farm boys in bare feet who had not yet begun to shave.

At the road junction, she spotted the largest group of black men she had ever seen in one place, forming in lines before marching out of the camp. Despite the fact that dozens of black soldiers had been among the best fighters at Lexington and Bunker Hill, despite the fact that hundreds had poured into Springfield to volunteer, when Congress had appointed the southern planter Washington as commander of the Continental Army, the new general had announced that there was no place for non-whites in this army. On the morning the announcement was made, Jemmy heard Dan and Henry mutter that this was a general, whose initial contributions to warfare had been to start the French and Indian War by slaughtering a party of French civilians in the wilderness, then getting surrounded and surrendering two months later. Morgan’s Virginians normally lived in a world, where everyone was valued, based solely on their ability to contribute. Henry and Dan both vowed that when hundreds of gutless white braggarts began deserting, they would do their best to change the mind of this bull-headed commander.

As she was walking, Jemmy thought about that appraisal of some of these white men here. A few sat with serious faces, melting lead to pour into bullet molds, but nearly everyone else was in high spirits now. A few had brought fiddles and were playing popular tunes of the day. Jemmy could pick out both Barbara Allen and Amazing Grace, drifting into the night air. There was much laughing, shouting, boasting.

Later on, as Jemmy passed the sentry at the command tent, she saw General Washington emerge with a figure she didn’t recognize, and she slowed her pace to eavesdrop.

“Of course, Colonel Arnold,” he was saying to a stooped figure, “take a week, if you need it. I don’t know what has gotten into Dr. Church and his committee. Demanding you to produce receipts for feeding your men in the Ticonderoga wilderness, before they will reimburse you, is absurd. Everyone knows there are precious few receipts on the frontier, and good book-keeping does not thrive under combat conditions. Why, Church makes you sound like a common criminal, defrauding the public! You would think that the man was on the other side. And, of course you must get home and see your family. My deepest sympathies again on the death of your wife. I understand that she passed, while you were taking Ticonderoga. Do they know what she died from?”

The stooped figure merely shook his head without so much as looking up.

Feeling like an eavesdropper, Jemmy’s sense of propriety overcame her naked curiosity, and she hurried off. Reaching her tent, she removed her shoes and worsted stockings, crawling into her bedding, exhausted. She pulled the ragged fringe of the blanket tight around her throat, more for emotional comfort than for warmth. She couldn’t stop thinking, though. How many of these carefree boys, she wondered, had ever faced a well-armed enemy? How many had ever survived a winter outdoors? Could they stand up to either?

Later, Henry crept in, thinking her asleep. He lay down silently in his buckskins, and she could tell from the familiar cadence of his breathing that he would soon be sleeping. The smell of his sweaty clothing encompassed her. Henry’s body odor had become almost overpowering of late. He was a man who had always perspired a lot, but had also bathed frequently. She had enough experience with the smell of her husband curled beside her to be able to sleep without noticing it. But something in that smell had changed these past few days. She couldn’t quite put her finger on it, but it seemed fouler than normal. It was as if some poison had gotten into Henry, and his pores were trying to push it out.

Jemima lay in the dark, contemplating it all, when another sound shattered her reverie. Henry coughed. Not once, not twice, but four or five times. Mixed into the sound was the painfully familiar gurgle of fluid in the lungs – the sound of consumption. So it had returned! He never woke, just rolled over, coughing again, unaware that she had begun to sob.

While she squinted wistfully into the smoke-wreathed night, Jemmy asked herself how it could ever have come to this. She had been through a great deal of suffering with Henry, but never gave leaving him a passing thought. When she became pregnant with her first child, she had stopped thinking about herself and began focusing on how to carve a better life for her child. She lost her second-born during a hard winter, which followed on the heels of a failed harvest. They had all been on reduced rations, and when fever swept through their cabin, little Becky had burned with fever, until one morning Jemmy had found her lying still, blue, and cold. She swore to herself then and there that no child of hers would ever again be weak from hunger. Henry had seemed to take the child’s death as a failure of his ability to support his family, and the episode had rekindled his efforts as well.

The following year, and really every year afterwards in their mountain valley at Harner’s Notch, the Warners had worked like a couple possessed. Neighbors began to comment on it. Going off to fight Indians had been the only time Henry had slackened his pace on the homestead. When he returned, he pitched into the place even more furiously than before. Year after year, they had expanded their fields and livestock, and the rest of their children had grown to maturity in good health. Life on the Warner farm had developed something of a comfortable air about it. Fear of starvation was long gone by the time Henry Jr. had come home with a fiancée. Certainly, they were nowhere near as prosperous as her father, and never would be, but what they owned was coveted by many a family – and all of it had come from the sweat and agony of their own labor. This, of course, made it all the sweeter. Together they had built a good life.

By the time the last of their boys left home at the age of twenty, Jemima and Henry were concentrating on reaping some of the rewards of their labors. Every glass of buttermilk, every bowl of cornmeal, every party they hosted, all were full of the immense satisfaction of having brought something meaningful into the world. With little beyond labor, love, and determination, they had wrought much, and they were proud of it. They looked forward to their “golden years of twilight”, as Reverend Silas put it. They would never, even for a second, feel guilty about what small degree of prosperity and security they had achieved.