Scotland 2002: Late summer in Scotland

Grazing ram on Conic Hill (385 m), Loch Lomond. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dusk at Loch nan Uamh, Sound of Arisaig. To the left a stranded boat with grafitti. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Evening light, Loch Hourn. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

By yon bonnie banks and by yon bonnie braes,

Where the sun shines bright on Loch Lomond,

Where me and my true love will never meet again

On the bonnie, bonnie banks of Loch Lomond.

Oh, you take the high road, and I’ll take the low road,

And I’ll be in Scotland afore ye,

But me and my true love will never meet again

On the bonnie, bonnie banks of Loch Lomond.

bonnie = beautiful, attractive

braes = hillsides

Scottish traditional song, according to some historians a Jacobite adaptation of an erotic song from the 18th Century, in which the lover dies for his king and takes the ‘low road’ of death back to Scotland.

Following the so-called Glorious Revolution in 1688, the Catholic Stuart King James II was deposited, and his daughter Mary II, who was a Protestant, ascended the throne. The Jacobites were a political-religious Catholic movement, named after the exiled King James (in Latin Jacobus), whom they supported. The movement was strong until at least the 1750s, especially in Scotland, Wales, and Ireland, but despite a number of wars and rebellions, the Jacobites never succeeded in restoring a Stuart on the British throne.

“The inn at Kinlochaline was the most beggarly vile place that ever pigs were styed in – full of smoke, vermin and silent Highlanders.”

(…)

“The next minute Alan had set the brandy bottle to my lips, and forced me to drink about a gill*, which sent the blood into my head again. Then, putting his hands to his mouth, and his mouth to my ear, he shouted, “Hang or drown!” and turning his back upon me, leaped over the farther branch of the stream and landed safe. I was now alone upon the rock, which gave me the more room; the brandy was singing in my ears; I had this good example fresh before me, and just wit enough to see that if I did not leap at once I should never leap at all. I bent low on my knees and flung myself forth, with that kind of anger of dispair that has sometimes stood me in stead of courage. Sure enough, it was only my hands that reached the full length; these slipped, caught again, slipped again; and I was sliddering back into the lynn** when Alan seized me, first by the hair, then by the collar, and with a great strain dragged me into safety.”

*Scottish gill = about 1 dl

**lynn = stream

From the novel Kidnapped (1886), by Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894), who made this note: “Kidnapped, being the memoirs of David Balfour of his adventures in the year 1751; how he was kidnapped and cast away; his sufferings in a desert isle; his journey in the West Highlands; his acquaintance with Alan Breck Stewart and other notorious Highland Jacobites; with all that he suffered at the hands of his uncle Ebenezer Balfour of Shaws.”

From Glasgow, I board a bus, bound for the village of Drymen, near Loch Lomond. The bus is a double-decker, and there is a fine view from the top deck. It is late summer, and the low hills have intense colours from two species of blooming heather, the common heather (Calluna vulgaris) and the bell heather (Erica cinerea). The specific name of the latter means ‘ash-coloured’ in Latin – not a very appropriate name for this gorgeously coloured plant.

A clever dog

In Drymen, I spend the night in a B&B, run by a friendly family. My talkative hostess says: “Our dog understands many languages. If you say: “Shut the door!” in your language, the dog will close the door.” So I say it in Danish, and, quite right, the dog runs to the door and shuts it. I am convinced that the woman has taught the dog to shut the door at a certain signal, and while my attention was focused on the dog, she probably gave the signal.

In the evening, I stroll to the village graveyard, which contains several fine old, lichen-covered tombstones. Near the small river Endrick Water I observe Canada goose (Branta canadensis) and rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) – both introduced and invasive species.

The Canada goose was introduced to Britain in the 1600s, when a few birds were released in St. James’s Park in London. Since then, numbers have exploded, and today the population is over 150,000 birds.

The rabbit was first brought to Britain as a hunting object by the Romans, following their invasion in A.D. 43, and today it is extremely common – an estimate in 2004 suggested about 40 million. In countless cases, it has done severe damage to the environment, partly through overgrazing, partly through its system of underground tunnels, and partly through competition with local wildlife. It is regarded as an invasive species in most countries.

In 1972, English author Richard Adams (1920-2016) wrote a novel, Watership Down, describing the life of a group of wild rabbits in southern England. Although the rabbits have been anthropomorphized, the story gives a fair account of their way of life.

Lichen-covered tombstones in evening light, Drymen. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The European rabbit was introduced to Britain almost 2,000 years ago, and today it is extremely common. These are sitting outside their den in the Spey Valley, Scotland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Up on Conic Hill

Early the following morning, I commence a 3-day hike along the famous Loch Lomond, so highly praised in Scottish folklore. My first goal is Conic Hill (385 m), situated near the village of Balmaha on the lake shore.

Now, the weather in Scotland is known for being quite unpredictable, but on this hike the weather gods are beneficial to me. The pale morning sun casts a yellowish light on a stone fence, on which the upper part consists of upright slabs, making it difficult to climb over it. Instead there are openings at regular intervals with gates to keep the sheep on the right side of the fence.

On my way towards Conic Hill, I come across a number of flowers, including the pretty foxglove (Digitalis purpurea) and black knapweed (Centaurea nigra). A honey buzzard (Pernis apivorus) circles above me, screaming.

The slopes of Conic Hill are gorgeously coloured by the two heather species. From the top of the hill there are splendid views over the beautiful Loch Lomond, with the outlet of Endrick Water. To the other side are grass fields, alternating with hedges and small woods.

Birdlife on the hill is rather scarce, I only observe whinchat (Saxicola rubetra), wren (Troglodytes troglodytes), meadow pipit (Anthus pratensis), and two soaring raptors, a common buzzard (Buteo buteo) and a kestrel (Falco tinnunculus). Many long-legged flies are sitting in the heather.

Far to the north is Ben Lomond, at 974 metres the highest mountain at Loch Lomond. In Gaelic, it is called Beinn Laomainn, which is generally translated as ‘Beacon Mountain’.

Old stone fence in morning sun, Drymen. The upper part of the fence consists of upright slabs, making it difficult to climb over it. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On my way towards Conic Hill, I found black knapweed. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Conic Hill (385 m). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Common heather, Conic Hill. The hill in the background is Ben Lomond. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bell heather is a gorgeous spectacle when blooming. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Loch Lomond, seen from Conic Hill, with the village of Balmaha, and the islands Clairinch (left), Inchcailloch (right), Torrinch, Creinch, Inchmurrin, and Arran. The white dots are sailboats. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Ochill Plateau, seen from Conic Hill. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hike along Loch Lomond

From Conic Hill, the trail descends steeply to Balmaha, where I find shelter for the night in a B&B. I stroll along the lake, but the tranquility is disturbed by the noise from a large number of speedboats. Bird life includes goosander (Mergus merganser), grey heron (Ardea cinerea), and greater black-backed gull (Larus marinus). Woodland germander (Teucrium scorodonia), a member of the mint family (Lamiaceae) with yellowish-white flowers, grows among the rocks.

The trail continues north along the lake shore to the village of Rowardennan, leading through rocky areas, heath, and forests with different types of trees, including oak (Quercus), hazle (Corylus avellana), and common alder (Alnus glutinosa), and various herbs, including small cow-wheat (Melampyrum sylvaticum) and hard fern (Blechnum spicant).

Many different birds live in these forests, and among the observed species are great spotted woodpecker (Dendrocopos major), robin (Erithacus rubecula), song thrush (Turdus philomelos), long-tailed tit (Aegithalos caudatus), treecreeper (Certhia familiaris), and coal tit (Periparus ater). Along the lake shore I encounter several grey wagtails (Motacilla cinerea).

Fishing boats and pleasure boats in late afternoon light, Balmaha, Loch Lomond. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The island of Inchfad, Loch Lomond. In the background Luss Hills. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ben Lomond in evening light, seen from Cashel, Loch Lomond. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Crinan Canal

I have arranged to meet with a Danish friend, Søren Lauridsen, in the village of Inverbeg, across the lake from Rowardennan. However, I miss the ferry and have to call Søren on his mobile phone. He then drives around the lake to pick me up in Rowardennan.

We now make a leisurely drive along the west coast of Loch Lomond to the village of Tarbet, from where a road leads to Loch Long and over a pass with breathtaking views to the beautiful town Inveraray, situated at the northern end of Loch Fyne.

About halfway between Loch Fyne and the Sound of Jura, we make a brief stop at Cairnbaan to watch the sluice gate at Bellanoch Bridge on the Crinan Canal, a 14 km long canal, which connects the village of Ardrishaig on Loch Gilp with the town of Crinan on the Sound of Jura. This canal was opened in 1801.

Hills and shadows from wandering clouds, Glen Croe Forest, Argyll, between Loch Long and Loch Fyne. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Far from the Madding Crowd.” – Cairndow, Loch Fyne. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sluice gate at Bellanoch Bridge, Crinan Canal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Standing stones and medieval castles

Near Kilmartin are many prehistoric megaliths, a group of standing stones, called Nether Largie, and a stone circle, called Temple Wood. (Numerous pictures, depicting standing stones and other megalithic structures, are shown on the page Culture: Megaliths.)

At Loch Awe, we make a brief stop to observe the ruins of Kilchurn Castle, situated on a rocky peninsula. This castle, which dates back to the mid-1400s, was the base of the Campbells of Glenorchy, the most powerful branch of the Clan Campbell. From around the 1430s, they dominated the central Highlands for about 200 years. When the Campbells became Earls of Breadalbane and moved to Taymouth Castle, Kilchurn fell out of use and lay in ruins by 1770.

In Morar, at the western end of Loch Morar, we stay at a B&B, where the friendly Thai hostess prepares a delicious Thai meal for us. In the evening, we have a magnificent vies of the Inner Hebrides from a nearby hill.

During a day visit to the Isle of Skye, the weather turns foul. It is raining most of the day, and the mountains are partly hidden in fog. Furthermore, the people here are rather aloof, so towards evening we return to our nice Thai hostess in Morar.

Prehistoric standing stones at Kilmartin, called Nether Largie, with resting sheep in the background. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Old stone bridge near Kilmartin. Numerous maidenhair spleenwort (Asplenium trichomanes), a species of fern, have sprouted between the stones. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

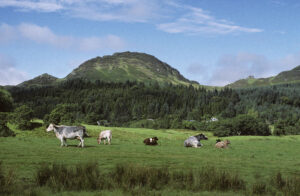

Grazing cattle near Ford (Oban). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kilchurn Castle, Loch Awe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sunset behind the Inner Hebrides, seen from Morar, with islands Eigg and, in the far distance, Rùm. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lealt Falls, 3 waterfalls with a combined height of 90 m, Isle of Skye. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mist envelops a rock formation, called The Old Man of Storr, Isle of Skye. In fact, the faces of two lying ‘ogres’ can be seen – one smaller to the left with a heavy eyebrow, a small nose, and a protruding lower lip, and a larger one to the right with a very long nose and also a protruding lower lip. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Joining the Fison family to Loch Hourn

In 1989, Danish fellow ornithologists and I were investigating bird life in Tanzanian coastal forests. Two of our contact persons were Tim and Ruth Fison, an English couple living in the village Narunyu in southern Tanzania, where Tim, who is a vet, was in charge of the cattle herds of the area.

I kept in touch with the Fisons, who later moved to Scotland. We have now arranged to meet at Spean Bridge, where I say goodbye to Søren and hello to the Fison family, Tim, Ruth, and their two sympathetic sons, Damien and Alastair, around 15 and 13 years old.

We now continue in Fison’s car to the inlet Loch Hourn, where they have borrowed a hut from friends. There is no road leading to the hut, and after fishing for sea trout (Salmo trutta) in the loch, Tim and the boys row a boat, laden with our luggage, to the hut, while Ruth and I walk through the birch forest along the shore. On our way, we find many golden chanterelles (Cantharellus cibarius), which we pick for our dinner.

Not many flowers are blooming at Loch Hourn, but I do encounter the ubiquitous bell heather, and also Devil’s bit (Succisa pratensis), common goldenrod (Solidago virgaurea), and common skullcap (Scutellaria galericulata). The rowans (Sorbus aucuparia) are gorgeous, with large bunches of bright orange-red fruits.

Mammals are numerous in this area, but due to the nocturnal habits of most species, I only observe harbour seal (Phoca vitulina), red deer (Cervus elaphus), and pygmy shrew (Sorex minutus). However, I am lucky to find tracks of wildcat (Felis sylvestris), and I also observe a playground of otters (Lutra lutra), and scats of red fox (Vulpes vulpes) and pine marten (Martes martes).

Birdlife includes raven (Corvus corax), red-throated diver (Gavia stellata), rock pipit (Anthus petrosus), twite (Linaria flavirostris), and stonechat (Saxicola rubicola). I also observe 3 species of amphibians, common toad (Bufo bufo), common frog (Rana temporaria), and smooth newt (Lissotriton vulgaris).

Now the weather turns foul, with dense mist and silent rain. But we endure, and Tim and Ruth continue roasting mackerels over a fire. As it turns out, they are delicious, with a faint taste of smoke.

Various views of Loch Hourn. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tim, Damien, and Alastair, catching sea trout, Loch Hourn. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On our way towards the hut, we found many golden chanterelles. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Channelled wrack (Pelvetia canaliculata), one of the many kelp species growing on the rocky coast along Loch Hourn. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flowers at Loch Hourn, from above bell heather, Devil’s bit, common goldenrod, and common skullcap. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fruiting rowan, Loch Hourn. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Despite the rain, Tim and Ruth continue roasting mackerels over a fire on the beach. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Uploaded May 2024)