Animal tracks and traces

These tiny sand balls on a beach near Tongxiao, western Taiwan, have been left here by small crabs, which cleaned their dens after high tide. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tracks of red deer (Cervus elaphus). In recent years, this species has increased significantly in numbers in Jutland, Denmark, where this picture was taken. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This leaf of giant taro (Alocasia macrorhiza), photographed in western Taiwan, has numerous holes, gnawed by insects. This plant is described in depth on the page Nature: Nature’s patterns. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bird tracks around a dead Launaea arborecens on a dune, Maspalomas, Gran Canaria. This bush is a member of the daisy family (Asteraceae). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Rabbits come out of the brush to sit on the sand in the evening, and the damp flats are covered with the night tracks of ‘coons, and with the spread pads of dogs from the ranches, and with the split-wedge tracks of deer that come to drink in the dark.”

From the novel Of Mice and Men (1937), by American author John Steinbeck (1902-1968).

This page deals with various forms of animal traces, including footprints, dens, nests, food items, gnawing marks, dung, diggings, etc.

Mammals

Bovidae Cattle, antelopes, and allies

Aepyceros melampus Impala

This rather large, but slender and graceful antelope constitutes the sole member of this subfamily. The male is a magnificent animal, with lyre-shaped horns, which may reach a length of 90 cm.

This species is common in much of eastern and southern Africa. Two subspecies are recognized, the nominate, which is distributed from southern Uganda and central Kenya southwards to eastern South Africa and the major part of Namibia, and subspecies petersi, known as black-faced impala, which is restricted to north-western Namibia and south-western Angola. This subspecies can be identified by the black markings on its face.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek aipus (‘high’ or ‘steep’) and keras (‘horn’), referring to the long horns of the male, whereas the specific name is from the Greek melas (‘black’) and pous (‘foot’), alluding to the black spots on its hind feet. The name impala is a corruption of the Tswana word phala, which means ‘red antelope’.

Two-banded courser (Rhinoptilus africanus), resting among impala pellets, Lake Manyara National Park, Tanzania. This bird is described on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in Africa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Canidae Dog family

This family is presented in depth on the page Animals – Mammals: Dog family.

Nyctereutes procyonoides Raccoon dog

Originally, this dog was distributed in eastern Asia, from Ussuriland southwards through eastern China to northern Vietnam, and also in Japan.

However, between 1928 and 1958, at least 10,000 raccoon dogs were released at various locations in the Soviet Union in an attempt to improve their fur quality. Many of these feral populations increased rapidly, and the species has spread to most countries in Europe, where it is regarded as invasive, being a threat to many breeding birds. (Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raccoon_dog)

Scats of raccoon dog, Alam-Pedja, Estonia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Vulpes vulpes Red fox

The most widespread of all canines, the red fox is found all across Eurasia (except tropical parts), in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa and the Nile Valley, and in North America, almost southwards to the Mexican border.

It has also been introduced to Australia, where it has become a menace to indigenous mammals and birds, and is regarded as highly invasive.

In cities, red foxes often become accustomed to people. This confiding pup was photographed in the Botanical Garden of Copenhagen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tracks of red fox on a frozen pond, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tale in the snow, Nature Reserve Vorsø: A red fox has killed and eaten a bird. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tracks of red fox, and of a mouse, in snow, Hardangervidda, Norway. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tracks of red fox on a muddy forest road, central Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Excreta of red fox with rose hip seeds and remains of crab shields, Nature Reserve Vorsø. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This scat shows that the fox has been eating crowberries (Empetrum nigrum), Thy, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Castoridae Beavers

Formerly, this family was a very diverse group of rodents, but is now restricted to a single genus, Castor, with 2 species.

These animals construct an underwater den beneath a huge pile of branches, which they have collected themselves. The den is made waterproof by stuffing water plants, twigs, leaves, and soil between the larger branches. In late autumn, the beavers collect a winter supply of branches, which are kept inside the den to serve as winter food for the animals.

Castor canadensis Canadian beaver

This species is native to the major part of North America, but has been introduced to various locations in Europe, and also to Patagonia, southern Argentina.

In 1937, 7 Canadian beavers were introduced to Finland, where they were released with the intention of letting them crossbreed with the local European beavers, to supplement the declining population.

However, the two species are not able to interbreed due to differences in their chromosome numbers, and today the European beaver has been replaced in most locations in Finland by the stronger Canadian beaver.

Beaver dens, Parker River National Wildlife Refuge, Massachusetts (top), and Acadia National Park, Maine. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This eastern white pine (Pinus strobus), which was growing at the edge of Crystal Lake, Massachusetts, has been felled by a Canadian beaver. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Beaver gnawing marks on an eastern white pine, Crystal Lake. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This black tupelo (Nyssa sylvatica) has been partly felled by a beaver, Crystal Lake. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Castor fiber European beaver

The European beaver was once widespread in Eurasia, but was hunted to near-extinction for its fur and for the so-called castoreum, a secretion from its scent gland, which was believed to have medicinal properties. Around 1900, only c. 1,200 beavers survived in 8 relict populations.

Today, it has been reintroduced to many areas, occurring in Scotland, and from northern Scandinavia southwards to France and thence eastwards across Russia and Kazakhstan to Sinkiang.

Tooth marks of a European beaver on the trunk of a Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris), Tammemäe, Estonia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cercopithecidae Old World monkeys

This large family, comprising 24 genera and about 140 species, is widely distributed in Africa and Asia. Members include baboons, macaques, colobus monkeys, langurs, and many others.

On the page Animals – Mammals: Monkeys and apes, many genera of this family are described.

Fallen acorns of spiny-leaved oak (Quercus semecarpifolia), some eaten by monkeys (macaques or langurs), Upper Langtang Valley, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chlorocebus pygerythrus Vervet

This small monkey is distributed from Ethiopia and southern Somalia southwards through Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Mozambique, and Botswana to South Africa. It lives mainly in savanna and open woodland, almost always near rivers, but is extremely adaptable and able to survive in cultivated areas, and sometimes in towns.

Vervets, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Vervet tracks on a beach, Kisiju, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Macaca cyclopis Taiwan macaque

As its name implies, this species is endemic to Taiwan, where it is quite common, from the lowlands to the highest mountains.

These fruits of Chinese screw palm (Pandanus tectorius, formerly P. odoratissimus var. sinensis) have been partly eaten by Taiwan macaques, Sheding Nature Park, Kenting National Park, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This twig, likewise in Sheding Nature Park, was bitten off by a Taiwan macaque, which ate a bit of the bark and then let it fall to the ground. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cervidae Deer

This large family contains 20 genera with about 90 species, with native species present in all continents, except Antarctica and Australia. They live in almost all types of habitats, ranging from tundra to tropical rainforest.

Deer are characterized by shedding their horns, called antlers, annually, when the mating season is over. While new ones emerge, they are covered by a layer of skin, called velvet. When the new antlers are complete, the velvet dies, creating an intense itching. To relieve this itching, the deer brushes the antlers against bushes or young trees, causing the velvet to loosen and fall off. This behaviour is called fraying. This fraying is often so violent that the bark of younger trees is removed all the way around the trunk, and the plant dies.

Many deer species use the same routes every day when foraging, and, over time, animal paths, called tracks, evolve.

Some species of deer have a habit of scraping aside withered leaves and vegetation, before they lie down on the forest floor.

Deer often wallow in mud to protect themselves from stinging insects.

Other information on this family is found on the page Animals – Mammals: Deer.

Capreolus capreolus Roe deer

This small deer is distributed all over Europe, with the exception of Ireland, far northern Scandinavia, Finland, and Russia. It is also found in Turkey, the Caucasus, and northern Iran.

From Ukraine and the northern flanks of the Caucasus, eastwards through the taiga zone to the Pacific Ocean, and also in Tibet, Korea, and Manchuria, this species is replaced by the Siberian roe deer (Capreolus pygargus). Formerly, these deer were regarded as a single species, but today most authorities recognize them as separate species. The Siberian roe deer is larger, with longer, more branched antlers than the European roe deer.

Roe buck, crossing a pond, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tracks of roe deer, and a leaf rosette of scentless mayweed (Matricaria perforata), central Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Track, urine, and pellets of roe deer, and tracks of blackbird (Turdus merula), Nature Reserve Vorsø. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Roe deer tracks, Funen, Denmark. In the lower picture, withered leaves have gathered in the track. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Scrapings of roe deer, Nature Reserve Vorsø. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Resting places of roe deer in a carpet of lesser celandine (Ranunculus ficaria) and white anemone (Anemone nemorosa), Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Resting place of a roe deer in tall grass, Funen, Denmark. The vegetation was too tall for the deer to scrape aside, so it simply lay down upon it. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A selection of antlers, shed by roe deer, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The trunk of this young wild cherry (Prunus avium) has a partly healed wound, after being frayed by a roe buck, Nature Reserve Vorsø. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This small common fir (Abies alba), which was formerly frayed by a roe buck, has withered in the top, but managed to grow a side branch. Lately, the buck has scraped in the forest floor to mark its territory. – Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The top of this young sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus) has died after being frayed by a roe buck, but new leaves are sprouting from the base of the tree. – Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A roe deer has eaten the tips of these leaves of ramsons (Allium ursinum), which have made their way up through withered leaves, Hansted Skov, eastern Jutland, Denmark. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cervus elaphus Red deer

Native to the major part of Europe, north-western Africa, Turkey, the Caucasus, northern Iran, and scattered locations in Central Asia, this species has also been introduced as a hunting object to other areas, including Australia, New Zealand, and North and South America.

In recent years, this species has increased significantly in numbers in Jutland, Denmark, where these pictures were taken.

Red deer tracks. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red deer tracks, crossing a forest road. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red deer tracks in a newly ploughed field. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red deer tracks in mud, and pollen from Norway spruce (Picea abies). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wallowing places for red deer. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red deer tracks. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Reindeer lichen (Cladonia), pruned by red deer. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Norway spruce (Picea abies), pruned by red deer. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Beech (Fagus sylvatica), pruned by red deer. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pellets of red deer. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pellets of red deer, overgrown by fungi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dama dama Fallow deer

Originally, this deer was indigenous to Turkey, the Caucasus, and Iran, and possibly also the Balkans and Italy. At an early stage, it was introduced to deer parks all over Europe, and in modern times, it has also been introduced to many other countries, including Australia, New Zealand, Argentina, and the United States. It often forms feral populations.

In the 1600s, fallow deer and red deer (above) were introduced to Jægersborg Deer Park, Zealand, Denmark, as hunting objects for the king and his retinue. Today, about 1,600 fallow deer and 300 red deer live in this park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In the 1200s, the island of Romsø, near Funen, Denmark, was the property of the king. He introduced fallow deer from Turkey and released them on this island as a hunting object. On this island, there were no wolves to prey on the deer, which was the case in most areas of Denmark in those days.

Fallow deer, Romsø. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These midland hawthorns (Crataegus laevigata) on Romsø have been extensively pruned by grazing fallow deer. – Hawthorns are described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Odocoileus hemionus Mule deer

This species, also called black-tailed deer, is found in the western half of North America, from southern Alaska southwards to Baja California and central Mexico. The name mule deer refers to its rather large ears, which, together with the black tail, distinguishes it from the white-tailed deer (below).

Mule deer stag with antlers in velvet, Yosemite National Park, Sierra Nevada, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Track of mule deer, Ronald W. Caspers Wilderness Park, Santa Ana Mountains, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dried-out pellets of mule deer in black lava, Kana’a Lava Flow, Coconino National Forest, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The common beavertail cactus (Opuntia basilaris) is distributed in dry areas of the Colorado Plateau, from southern Utah and Nevada, western Arizona, and eastern California, southwards to north-western Mexico. In May, this species displays wonderful pink or rose-coloured flowers.

Chomp! – Pads of this common beavertail cactus in Red Rock Canyon State Park, California, have been partly eaten, probably by a mule deer. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Odocoileus virginianus White-tailed deer

This medium-sized deer is one of the most widespread deer species in the world, found in most of North America, Mexico, Central America, and northern South America, southwards to Peru and Bolivia. It has also been introduced elsewhere, including Cuba, Jamaica, New Zealand, Finland, and the Czech Republic.

It is regarded as an invasive in Finland and New Zealand, and also in parts of its native United States. You may read more about this issue on the page Nature: Invasive species.

Female white-tailed deer, Cathlamet, Washington State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This American holly (Ilex opaca) on Fire Island, Long Island, New York, has been pruned by white-tailed deer. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chiroptera Bats

Counting more than 1,400 species, bats constitute the second largest order of mammals after rodents, comprising about 20% of all mammal species worldwide.

The Gomantong Caves are a huge system of limestone caves in the Sandakan District, Sabah, Borneo, whereas the Niah Caves are similar caves in the Miri District of Sarawak, likewise in Borneo.

These caves are famous for housing huge colonies of bats (more than a quarter of a million in Gomantong), and also hundreds of thousands of swiftlets of the genus Aerodramus. The guano from these bats and birds have accumulated on the floor of the caves, forming a thick layer.

Various animals, including cave cockroaches (Pycnoscelus striatus) and water scavenger beetles (Cerycon gebioni), feed on this guano, while others feed on dead bats and swiftlets.

Cave cockroaches and water scavenger beetles, feeding in a thick layer of bat dung and remains of insects from bat food, Gomantong Caves. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This cave cockroach is feeding on the remains of a dead frog, which perished in the bat dung, Gomantong. Presumably, the frog had entered the cave by mistake. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cave cricket (Rhaphidophora oophaga), feeding on a dead bat of the genus Hipposideros, Niah Caves. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cricetidae Voles and allies

This huge family of small to medium-sized rodents includes voles, lemmings, hamsters, and New World rats and mice, counting about 112 genera and 600 species. They are distributed in Europe, Asia, and the Americas.

Numerous dried-out pellets of an unidentified mouse (and a single rabbit pellet), Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Arvicola amphibius Water vole

As its specific name implies, this species has a semi-aquatic way of life. It is derived from the Greek amfi (‘both sides’) and bios (‘life’), thus ‘the one that lives on both sides’.

This rodent is widely distributed, from northern Scandinavia and Siberia southwards to Italy, Greece, Turkey, northern Iran, and Kazakhstan, and from the British Isles eastwards to eastern Siberia.

Water vole, encountered in Nature Reserve Klægbanken, Ringkøbing Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Remains of reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea), left by a water vole, Nature Reserve Klægbanken. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tracks of water vole and red fox (Vulpes vulpes) in snow, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Water vole hills, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Microtus agrestis Field vole

This vole lives in a wide range of habitats, including meadows, fields, plantations, woodlands, heaths, dunes, and marshes, and along rivers.

It is distributed in all of Europe, except Iceland, Ireland, southern Spain, Italy, and the Balkans, and thence eastwards across Siberia to east of Lake Baikal. In the Alps, it is found up to about 1,700 m altitude.

At some time during the winter, the bark of this young hawthorn (Crataegus) in Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark, has been eaten all the way around the trunk by field voles, resulting in the death of the shrub. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This hybrid crack willow (Salix x rubens), likewise in Nature Reserve Vorsø, was felled in the autumn, and during the winter, parts of the bark was eaten by field voles. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Elephantidae Elephants

Elephants and their sad fate are described in depth on the page Animals – Mammals: Rise and fall of the mighty elephants.

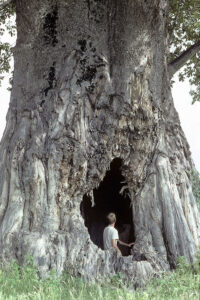

The common baobab (Adansonia digitata) is the most widespread among the nine species in this genus, of which six are native to Madagascar, two to mainland Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, and one to Australia. The bark of this majestic tree is a popular food item among elephants (Loxodonta africana), who often peel off the bark with their tusks. The tree may become so damaged by this treatment that it will topple during the next storm.

This magnificent tree is described on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees.

Elephants, eating bark from a fallen baobab, Tarangire National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This hollow baobab, likewise in Tarangire, has been partly destroyed by elephants. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Not only the bark, but also the wood of this baobab in Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe, has been tremendously frayed by elephants. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Elephant dung often attracts butterflies, which suck nutrients from it. This picture shows butterflies of the genus Dixeia, family Pieridae, Meru National Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Southern yellow-billed hornbills (Tockus leucomelas), feeding on insects in elephant dung, presumably dung beetles (see below), Krüger National Park, South Africa. Many species of hornbill are described on the page Animals – Birds: Hornbills. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Felidae Cats

Following genetic studies, this family is today divided in two subfamilies, Pantherinae with 5 large species in the genus Panthera and 2 smaller in the genus Neofelis, and Felinae, encompassing the remaining 34 species, divided into 10 genera. Cats live on all continents with the exception of Australia and Antarctica.

Panthera onca Jaguar

With a body length of up to 1.85 m and weight of up to about 95 kg, the jaguar is the largest cat in the Americas and the third largest in the world after lion and tiger. It is distributed from the extreme southern Arizona through Mexico and Central America southwards to Paraguay and northern Argentina, living mainly in forests.

Jaguar pugmarks on a sandy beach, Tortuguero National Park, Limón, Costa Rica. The leaves are beach morning-glory (Ipomoea pes-caprae). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Panthera uncia Snow leopard

This elusive cat lives in mountains of Central Asia, but has been hunted to extinction in many areas because of its rich and beautiful fur. In Buddhist areas of the Himalaya, hunting is banned, and in these areas this rare cat has safe havens. It is described on the page Animals – Mammals: Mammals in the Himalaya.

One morning, in the Jarsang Khola Valley, Annapurna, Nepal, we found these partly melted pugmarks in the snow, signifying that a snow leopard had passed here the previous night. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Puma concolor Cougar

This large cat, also known as puma or mountain lion, has a very wide distribution, found from the Yukon area in Canada southwards through western North America to the southern Andes of South America. It is very adaptable, found in almost all habitat types of this vast area.

Cougar scat on a gravel road, Volcán Arenal National Park, Cordillera de Tilarán, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hominidae Apes and Man

Gorillas, chimpanzees, and orangutans are described in depth on the page Animals – Mammals: Monkeys and apes.

Gorilla beringei Mountain gorilla

The mountain gorilla lives in montane forests of eastern Zaire, north-western Rwanda, and south-western Uganda. This region has been subject to war and civil war for many decades, during which gorillas also fell victim.

Today, however, the population of subspecies beringei, which counts only about 900 individuals, is the only great ape in the world that has increased in number lately, whereas subspecies graueri has been severely affected by human activities, most notably poaching for commercial trade of bushmeat. This illegal hunting has been facilitated by a proliferation of firearms from the various wars in this region.

This spot on the forest floor in Bwindi National Park, Uganda, was used as a night resting place by a mountain gorilla, which left a pile of dung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pan troglodytes Chimpanzee

Comprising 4 subspecies, the chimpanzee has a discontinuous distribution from southern Senegal east across the forested belt north of the Congo River to extreme western Tanzania and Uganda, living in various types of forest, along rivers in savanna woodland, and sometimes in plantations, from the lowland up to app. 2,800 m altitude.

The chimpanzees in Gombe Stream National Park, western Tanzania, were made famous by celebrated primatologist Jane Goodall (born 1934) – the first person to study these apes in depth.

Faeces of chimpanzee with remains of hard-shelled fruits, Gombe Stream National Park. A bluebottle is sitting on the excrement. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Leporidae Hares and rabbits

This family, containing more than 60 species, has members on all continents, except Antarctica. In Australia, the European rabbit (below) has been introduced.

Lepus europaeus European hare

This animal is native to the major part of Europe and the Middle East, and thence eastwards across the steppes of Asia to Mongolia. It has also been introduced elsewhere, including Britain, Australia, New Zealand, and southern South America.

European hare in a littoral meadow, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hares often use the same routes every day when foraging, and, over time, animal paths, called tracks, evolve. This picture is from a littoral meadow in western Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Oryctolagus cuniculus European rabbit

This rabbit has been introduced to many countries as a hunting object, including Britain, Denmark, Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii, and South Africa. In countless cases, the rabbit has done severe damage to the environment, partly through overgrazing, partly through its system of underground tunnels, and partly through competition with local wildlife. It is regarded as an invasive in most countries.

It is described in depth on the page Nature: Invasive species.

Dried-out dung pellets of European rabbit on the island of Fanø, Denmark. Rabbits were introduced to this island in 1913, and today it is extremely common here. The grass-tuft is grey hair-grass (Corynephorus canescens), which is common on this island. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Muridae Old world mice and rats

This is the largest mammal family, containing more than 700 species of mice, rats, and allies, native throughout Eurasia, Africa, and Australia, but accidentally introduced to the rest of the world.

The family name is derived from the Latin mus (genitive muris), meaning ‘mouse’.

Kernels of cherry plum (Prunus cerasifera), gnawed by mice, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rattus True rats

A genus of about 64 species, native to Asia. Several species have been accidentally introduced elsewhere, especially the brown rat (below) and the black rat (Rattus rattus).

Rattus norvegicus Brown rat

The brown rat originated somewhere in Asia, but has spread with humans to almost all parts of the world. It is a serious pest, as it competes with native mammalian species, raids birds’ nests, and consumes huge amounts of cereals and other food items. Furthermore, it spreads various diseases among humans. During the Middle Ages, fleas of the brown rat were carrying bubonic plague, which in some places reduced the human population by 50 to 75%. This much feared disease was aptly named The Black Death.

This brown rat has been killed by a cat, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mustelidae Mustelid family

This family of small to medium-sized carnivores, comprising 25 genera with about 60 species, includes weasels, martens, badgers, otters, and many others.

Lutra Otters

A small genus of semi-aquatic mustelids, with only 2 living species, the widespread common otter (below) and the Sumatran otter (L. sumatrana), which is confined to parts of Southeast Asia. 12 other members of the genus have become extinct at various times, including the Japanese otter (L. nippon), which was last seen as late as 1979.

Lutra lutra Common otter

A very widespread species, living in freshwater and saltwater habitats from the entire Europe in a belt across central and southern Siberia to Sakhalin Island, southwards to northern Africa, Turkey, Iran, the Himalaya, and China, with isolated populations in South India, Sri Lanka, and Sumatra.

Otter track, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Excreta of otter, Vorsø. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Footprint of a young otter, Vorsø. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Martes Martens

Marten footprints on a snow-covered tree trunk, either of pine marten (Martes martes) or stone marten (M. foina), Elling Skov, north of Horsens, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Meles meles European badger

One of the largest members of the family, the badger is distributed in almost all of Europe and the Middle East, eastwards to the Pamir Mountains of Afghanistan, divided into 8 subspecies.

From western Russia eastwards across Central Asia to Ussuriland, Korea, and China, it is replaced by the paler Asian badger (Meles leucurus), and in Japan by the Japanese badger (Meles anakuma), which is brownish, with very faint facial stripes.

The badger lives in large family groups in dens, often ten or more animals together. This complex in Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark, has no less than c. 30 entrance holes. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The badger has a habit of defecating at places, where it has been digging for roots, larvae, bumblebee nests, etc. – Nature Reserve Vorsø. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Badgers use the same routes every day when foraging, and, over time, paths, called tracks, evolve. – Vorsø. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tracks of European badger on a sandy beach, Vorsø. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Phocidae Earless seals

These seals differ from fur seals and sea lions, of the family Otariidae, through their lack of external ears. Likewise, they are unable to use the front flippers as feet, for which reason they are sometimes called crawling seals. With the exception of the monk seals, most species are confined to colder climates.

Mirounga angustirostris Northern elephant seal

Elephant seals derive their name from their great size, and also from the male’s large, inflatable proboscis, with which he makes loud roaring noises, especially during the mating season.

Formerly, the northern elephant seal was hunted extensively for its blubber, from which oil was made. By 1869, it had almost been extirpated, and around 1890 only one group, comprising about 100 animals, was known to exist. However, it managed to survive, and since the early 20th century it has been protected by law in Mexico and the United States. Subsequently, it has now recovered, counting more than 200,000 individuals. Today, it occurs in scattered colonies along the Pacific Coast, from Baja California to the Gulf of Alaska and the Aleutian Islands.

When moulting, elephant seals spend a lot of time sleeping. In this picture, American herring gulls (Larus smithsonianus) are fighting over faeces that have just been delivered by an immature elephant seal. – San Simeon, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Procyonidae Raccoons and allies

Nasua narica White-nosed coati

This animal is described in depth on the page Animals – Mammals: Long-nosed coatis – charming bandits.

Tracks of white-nosed coati on a sandy beach with a fallen coconut (Cocos nucifera), Corcovado National Park, Peninsula de Osa, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Procyon lotor Raccoon

This animal is very common in North and Central America, from central Canada southwards to Panama. It has also become naturalized in large parts of Europe, the Caucasus, and Japan. In many places, it is regarded as a pest, plundering birds’ nests and competing with local mammals. In America, it is a nuisance in urban areas, as it will turn over garbage cans, looking for food, and spread the garbage over large areas. It also consumes food at bird feeders, if the food is not being placed out of reach.

The word raccoon was adopted by settlers in Virginia, a corruption of a Powhatan term, meaning ‘the animal that scratches with its hands’. It was variously written as aroughcun or arathkone.

Tracks of raccoon, Crescent Beach, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rhinocerotidae Rhinos

These pachyderms, comprising 5 species, are distributed in warmer areas of eastern and southern Africa, India, Nepal, Southeast Asia, and Indonesia.

Rhino parts have been used as ingredients in traditional Asian medicine for at least 2000 years, and today all 5 species are critically endangered due to widespread poaching, in Asia also due to habitat loss. This issue is described in depth on the page Folly of Man.

Ceratotherium simum White rhino, square-lipped rhino

This species has 2 subspecies, the southern white rhino, counting about 20,000 individuals, mainly found in South Africa, and the northern white rhino, which is virtually extinct, with only 2 animals surviving, both in captivity.

Rhino dung attracts butterflies, as in this picture from Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe, which shows burnet moths, and a single dung beetle (see below). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sciuridae Squirrels

A huge family with about 51 genera and c. 300 species, distributed in the major part of the Americas, Eurasia, and Africa. They have also been introduced by humans to Australia.

The family name is derived from Sciurus, the Latin name of these animals, in 1758 applied by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) to the Eurasian red squirrel (below). The word squirrel, which has been in use as early as 1327, is from the Anglo-Norman name esquirel, which is again from the Old French escurel, a corruption of the Latin sciurus, which is derived from Ancient Greek skia (‘shadow’) and oura (‘tail’), thus ‘shadow-tailed’, alluding to the habit of some squirrels to raise their bushy tails over the body, thus creating shade.

Many species of squirrel are presented on the page Animals – Mammals: Squirrels.

A rodent, probably a squirrel, has opened these walnuts (Juglans regia) and eaten the nuts, Dharkot, Uttarakhand, northern India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Callosciurus erythraeus Red-bellied squirrel, Pallas’s squirrel

This animal is widespread, found from eastern Nepal, Bhutan, and north-eastern India eastwards to Indochina, southern China, and Taiwan. More than 30 subspecies have been described, although not all are recognized by many authorities.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek erythros (‘red’), alluding to the belly, which is often – but not always – reddish.

Nest of red-bellied squirrel, subspecies taiwanensis, in the top of a silk-cotton tree (Bombax ceiba), Taichung, Taiwan. This subspecies is common and widespread at lower elevations on the island. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cynomys ludovicianus Black-tailed prairie dog

Prairie dogs, of the genus Cynomys, are a type of ground squirrels, which live in large underground colonies on the North American prairie, popularly called ‘prairie dog towns’. Each family has several entrances to their ‘apartment’. These entrances are at different levels, causing an air current to flow through the tunnels, which will supply fresh oxygen to the animals. The soil, which has been dug up, creates a bank around the den, preventing rain water from pouring into it.

Black-tailed prairie dogs, gathered around their den, Badlands National Park, South Dakota. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Petaurista albiventer White-bellied giant flying squirrel

The white-bellied giant flying squirrel is distributed from north-eastern Afghanistan eastwards along the Himalaya to Nepal, occurring at altitudes between 150 and 3,000 m. Its upperparts are reddish-chestnut with many whitish hairs, whereas the underside, throat, and cheeks are whitish. The tail is brown, often with a black tip.

Previously, this species was regarded as a subspecies of the widespread red giant flying squirrel (P. petaurista). However, recent genetic research has split that species into a number of separate species. The white-bellied was also formerly reported eastwards to the Yunnan Province, but eastern Himalayan animals are now recognized as belonging to a recently described separate species, the Yunnan giant flying squirrel (P. yunanensis).

Indian forester B.P. Bahuguna shows a leaf of spiny-leaved oak (Quercus semecarpifolia), which has been partly eaten by a giant flying squirrel. The squirrel always eats only part of the leaf, by folding it up and biting the central, less toxic part. During a hike up the Asi Ganga Valley, Uttarakhand, northern India, we found many such leaves along the trail. This hike is related in detail on the page Travel episodes – India 2008: Mountain goats and frozen flowers. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ratufa indica Indian giant squirrel, Malabar giant squirrel

This species is endemic to India, found from Rajasthan and Bihar southwards to the southern Western Ghats, near the southern tip of India. It mainly lives in forests and woodlands in hilly areas. It is strictly arboreal, and most of its food consists of leaves, fruits, and seeds.

The seeds of this huge pod of a leguminous tree (Fabaceae) have been eaten by an Indian giant squirrel, Mahaveer Wildlife Sanctuary, Goa, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sciurus vulgaris Eurasian red squirrel

Despite its name, the coat of this animal varies from bright rufous to black, not only between separate populations, but also within a single population. Regardless of the colour, the belly is always whitish.

This species is common and very widely distributed, from the major part of Europe eastwards across the Siberian taiga to the Kamchatka Peninsula, and thence along the Pacific coast southwards to north-eastern China, Korea, and the Japanese island Hokkaido. There are also scattered populations in Central Asia, and a separate population in the Caucasus.

The seeds of these spruce cones have been eaten by a red squirrel, Nørlund Plantation, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Scales from a cone of Nordmann’s fir (Abies nordmanniana), gnawed by a red squirrel, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Soricidae Shrews

Shrews are tiny insectivores, counting about 385 known species, which are distributed almost worldwide, with the exception of New Guinea, Australia, New Zealand, and Antarctica.

Apart from owls, very few animals eat shrews, as they undoubtedly taste extremely bad because of the strong, pungent smell, emitted from their anal gland. This smell is utilized to mark territory, create scent trails, communicate with other shrews, and, finally, as a defense mechanism. The latter is often not sufficient to deter carnivores from killing them, but the smell is so powerful that the carnivores will not eat them. This is why you so often come across dead shrews in nature.

Neomys fodiens Water shrew

One of the larger shrew species, to 10 cm long, and with a tail to 7 cm long. The fur on the back is almost jet-black, contrasting strongly with the white belly. It has stiff hairs around the feet and along the tail, an aid to its semi-aquatic life. It is an excellent swimmer, catching prey by diving. It is distributed from northern Europe southwards to northern Spain, Italy, and the Balkans, eastwards across central Asia to Russian Ussuriland and Sakhalin.

Sorex araneus Common shrew

As its name implies, this animal is widespread, and, in fact, one of the most common mammals in northern Europe. It is found in forests, scrubland, and grasslands, from England eastwards to southern central Siberia and Mongolia, and from northern Scandinavia southwards to the Pyrenees and northern Greece.

It may be told from the water shrew by its smaller size, brownish back, and greyish belly.

In his delightful book The Naming of the Shrew (2014), English author John Wright says: “It may sound extraordinary, but until recently the shrew had a most fearsome reputation. The creature’s bite was likened to that of a spider – araneus in Latin. Both Aristotle1 and Pliny2 wrote of its venomous nature, and this belief continued down the centuries, gaining momentum as time went by. The general feeling was summed up neatly by the Reverend Topsell3 in his seventeenth-century History of Four-footed Beasts and Serpents: ‘It is a ravening beast, feighning itself gentle and tame, but, being touched, it biteth deep, and poisoneth deadly. It beareth a cruel minde, desiring to hurt anything, neither is there any creature that it loveth, or it loveth him, because it is feared of all.’

Not that an actual bite was considered necessary for the shrew to do its evil work. Elyot4 in 1538 wrote: ‘Mus araneus, a kynde of myse called a shrew, whyche, yf it goo ouer a beastes back, he shall be lame in the chyne.’ (Chyne here means ‘spine’).”

1Greek scientist and philosopher Aristotle (384-322 B.C.).

2Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder (23-79 A.D.).

3English cleric and author Edward Topsell (c. 1572-1625).

4English diplomat and scholar Thomas Elyot (c. 1496-1546), in his The Dictionary of syr Thomas Eliot knyght.

Water shrew (top) and common shrew, killed by cats and left in a farm yard, Funen, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Suidae Pigs

Members of this family, counting 18 or 19 species, are native to Europe, Asia, and Africa. Some authorities recognize the domestic pig as a separate species, Sus domesticus, others regard it as a subspecies of the wild boar (below).

The domestic pig is described on the page Animals: Animals as servants of Man.

Sus scrofa Wild boar

This pig is found in a vast area, from almost all of Europe and North Africa across the Middle East and Central Asia to Japan, and thence southwards to Sri Lanka, the Philippines, Sumatra, and Java. It has also been introduced elsewhere, notably the United States, Australia, and New Guinea.

I once had a close encounter with a wild boar, see Travel episodes – Iran 1973: Car breakdown at the Caspian Sea.

An amusing account of wild boar, described by the famous hunter and conservationist Jim Corbett (1875-1955), is related on the page Quotes on Nature.

Diggings of wild boar, De Hoge Veluwe National Park, Holland (top), and near Kutumsang, Langtang National Park, central Nepal. Presumably, the animals were searching for tubers. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Talpidae Moles and allies

Moles, shrew-moles, and desmans are insectivores, which have adapted to an underground life, where they feed on worms and other invertebrates. They include 19 genera and about 60 species, distributed across the Northern Hemisphere.

Moles are occasionally found dead, presumably killed by foxes, dogs, or cats. As they are not eaten, one may assume that they, like shrews, are ill-tasting.

In 1989, German professor Werner Holzwarth (born 1947) wrote a fantastic children’s book, Vom kleinen Maulwurf, der wissen wollte, wer ihm auf den Kopf gemacht hat, illustrated by Wolf Erlbruch (born 1948). In 1993, it was published in English, titled The Story of the Little Mole Who Went in Search of Whodunit. It tells the story about a mole who sticks his head out of his hole one morning, and gets a load of shit on his head. He then embarks on a journey to find the culprit. Read it and have a great laugh!

Mogera insularis Formosan mole

Taxonomically, this species has been moved about a great deal, since it was first described in 1863 by English diplomat and naturalist Robert Swinhoe (1836-1877). Initially, it was named Talpa insularis, but was later regarded as a subspecies of La Touche’s mole (today named Mogera latouchei) of mainland China and northern Vietnam. Later, the Formosan mole was renamed Mogera insularis and lumped with a mole from Hainan Island. However, the Hainan moles are today regarded as a separate species, M. hainana, and, furthermore, moles from the western lowlands of Taiwan are now considered a distinct species, Kano’s mole (M. kanoana).

Dead Formosan mole, Guanxi, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Talpa europaea European mole

This well-known animal is distributed from Scotland, Denmark, southern Sweden and southern Finland southwards to southern France, northern Italy, and the northern part of the Balkans, eastwards to western Siberia.

Dead European mole in its den, Zealand, Denmark (arranged situation). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mole hills in a field, central Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this picture, a mole has managed to press up soil across a hard forest road, central Jutland – testimony to the extreme strength of moles. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ursidae Bears

A small family with 8 species, distributed in Europe, Asia, North and South America, and the Arctic. Bears have disappeared, or become very rare, in many areas, including Europe, Southeast Asia, Korea, China, and Taiwan, as they have been shot illegally to supply the various markets of eastern Asia with ingredients for production of traditional medicine, and to make bear paw soup. More about this subject is found on the page Folly of Man.

Melursus ursinus Sloth bear

This bear is widespread in the Indian subcontinent, found from Rajasthan, southern Nepal, and Bhutan southwards to Sri Lanka. However, it has declined in later years due to loss of habitat, as many areas have been transformed to farmland. It mainly feeds on fruits, ants, and termites. It is also called labiated bear due to its long lower lip, used for sucking up insects.

Track of sloth bear on a sandy road, Anshi National Park, Karnataka, India. Note the separate marks from the exceptionally long claws of this bear. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ursus americanus American black bear

This smallish bear is very widely distributed in North America, found from Alaska and northern Canada southwards to central Mexico. Due to shrinking areas of suitable habitats, this bear has become a nuisance in many suburban areas of the United States, searching for edibles in garbage cans and other places.

This American black bear cub is eating seeds of a sugar pine cone (Pinus lambertiana), Sequoia National Park, Sierra Nevada, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Scats of American black bear, Kings Canyon National Park, Sierra Nevada (top), and Okefenokee Swamp, Georgia, both containing undigested pine seeds. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ursus arctos Brown bear

Divided into 10 subspecies, this large bear is distributed in many parts of northern and central Eurasia and north-western North America. The vary greatly is size between the different subspecies, weighing from 80 to 600 kg. The colour of the coat also varies and may be dark brown, yellowish-brown, reddish, or creal-coloured.

Tracks of a brown bear, subspecies collaris, on a sandy beach, Chukotka Peninsula, eastern Siberia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ursus thibetanus Asian black bear

This bear, also known as moon bear or white-chested bear, was previously named Selenarctos thibetanus. In former days, this animal had a much larger distribution in Asia, but illegal hunting has had the effect, that today only scattered populations are found in Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, the Himalaya, Southeast Asia, China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan, and Ussuriland in south-eastern Siberia.

Asian black bear, photographed in Chengdu Zoo, Sichuan Province, China. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Scats of Asian black bear, containing hairs and bone splinters, Ghunsa Valley (top) and Sagarmatha National Park, both in eastern Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this picture from Great Himalayan National Park, Himachal Pradesh, India, an Asian black bear has been digging for tubers. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Scratch marks from an Asian black bear on a trunk of Himalayan birch (Betula utilis), Great Himalayan National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Viverridae Civets

This family, which includes civets, palm civets, and genets, comprise 15 genera with 38 species, distributed in Africa, southern Europe, and warmer parts of Asia.

Civettictis civetta African civet

This animal, formerly known as Viverra civetta, is widely distributed in open woodland and secondary forest of sub-Saharan Africa. It is rather common, but is locally threatened by hunting. Wild individuals are also caught and kept in captivity to produce civetone for the perfume industry.

African civets often defecate on the same spots, creating large heaps of dung, called ‘toilets’.

Dung heap of an African civet, observed near the town of Samfya, northern Zambia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Paguma larvata ssp. tytleri Andaman palm civet

As its name implies, this subspecies of the Southeast Asian masked palm civet is restricted to the Andaman Islands, close to Myanmar. It was perhaps introduced to these islands by settling negrito peoples, and has since formed feral populations.

Excreta of Andaman palm civet, containing palm seeds, John Lawrence Island, Andaman Islands. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Birds

A raptor (peregrine or goshawk) has eaten the major part of this common teal (Anas crecca), Thy, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Apodidae Swifts

This family contains about 19 genera and 113 species of fast-flying birds, which catch insects in the air. They are superficially similar to swallows, but are not even distantly related to them, the resemblance being a result of convergent evolution due to similar life styles.

On this page, swifts are dealt with in the caption Chiroptera above.

Fringillidae Finches

A large family with about 228 species, divided into 50 genera. They are distributed worldwide, except for Australia and the polar regions. Most species have stout conical bills, adapted for eating seeds and nuts.

The family name is from the Latin fringilla (‘finch’), derived from frigutio (‘I chirp’).

Chloris chloris Greenfinch

This finch is found in all of Europe, except Iceland, eastwards to the Ural Mountains and Kazakhstan, southwards to northern Africa, Iraq, and northern Iran.

Hips of Rosa rugosa are a popular food item of the greenfinch. This picture was taken in Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hirundinidae Swallows and martins

A large family with 19 genera and about 90 species, distributed around the world on all continents, including Antarctica, where the barn swallow (Hirundo rustica) is an occasional visitor. The greatest diversity is found in Africa.

In Europe, the term swallow is mainly used for species with forked tails, martin mainly for species with squarish tails. In America, however, the term martin is reserved for members of the genus Progne.

Riparia Sand martins

A genus of 6 small, brown and white martins, widely distributed in the Old World. The common sand martin (below) also breeds in North America.

The nests of these birds are placed many together at the end of tunnels, up to about 1.2 m long, which the birds dig into sand or gravel banks. This fact is reflected in the generic name, which is derived from the Latin ripa (‘riverbank’).

Riparia riparia Common sand martin

This bird, in America known as bank swallow, breeds in a vast area, covering subarctic and temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere. In autumn, it migrates to Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America.

Breeding site of common sand martin, Marais de Mousterlin, Bretagne. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Laridae Gulls, terns and skimmers

This cosmopolitan family constitutes 22 genera with about 100 species. A large number of species are described on the page Animals – Birds: Gulls, terns and skimmers.

Tracks of large gulls, either herring gull (Larus argentatus) or greater black-backed gull (L. marinus), around a dead pup of harbour seal (Phoca vitulina), Thy, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chroicocephalus ridibundus Black-headed gull

This small gull breeds from southern Greenland and Iceland across most of Europe and temperate areas of Asia, eastwards to Kamchatka, Russian Ussuriland and north-eastern China. It is also a rare breeding bird in north-eastern North America. It winters in Europe, northern Africa, the Middle East, the Indian Subcontinent, Southeast and East Asia, Japan, and along the east coast of North America.

The specific name is from the Latin ridere (‘to laugh’), referring to one of its calls, ke-ke-ke, mostly heard in the breeding colonies.

For hundreds of years, Hirsholmene, a group of islets in northern Kattegat, Denmark, have housed large colonies of birds, breeding in the thousands, including black-headed gull, in this picture seen above the colony at sunset. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The windows of an observation tower near the colony of black-headed gulls on Hirsholmene have had their share of guano from the birds. A black-headed gull is standing on the railing. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Larus argentatus Herring gull

Previously, the herring gull was regarded as being a circumpolar species, divided into a number of subspecies. Today, however, it has been split into several species, and the herring gull proper is restricted to north-western Europe, from Iceland, northern Norway and north-western Russia, southwards along the coasts of the Baltic Sea, North Sea, and the Atlantic Sea, to southern France.

In later years, numbers of European herring gulls have increased significantly in cities, where the birds place their nest on top of high-rise buildings.

It is known that herring gulls often drop mussels on hard surfaces, so that the shells break, and the gull can extract the animal.

Broken shells of blue mussel (Mytilus edulis), dropped by herring gulls, Nyborg, Denmark. The plants are buck-horn plantain (Plantago coronopus) and biting stonecrop (Sedum acre). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Muscicapidae Old World flycatchers

Genetic research has revealed that many smaller birds, which were formerly regarded as belonging to the thrush family (Turdidae), are in fact flycatchers. Today, the family includes about 51 genera with c. 324 species, widely distributed in Africa and Eurasia. The family name is derived from the Latin musca (‘a fly’) and capere (‘to catch’).

Oenanthe Wheatears

Following a number of genetic studies, this genus today contains about 32 species, as members of the former genus Cercomela are now included in Oenanthe.

These birds are widely distributed in Europe, Asia, and Africa, with a single species, the northern wheatear (below), also breeding in Greenland and eastern Canada, and in Alaska and western Canada.

The generic name is derived from the Greek oenos ‘wine’ and anthos (‘flower’), alluding to the northern wheatear returning from Africa to Greece in spring, when the grapevines blossom.

The common name is an old folk name of the northern wheatear, meaning ‘white arse’, referring to the conspicuous white rump of the bird.

Oenanthe oenanthe Northern wheatear

The northern, or common, wheatear breeds in a vast area, in almost the entire Europe, from Iceland and northern Norway southwards to the Mediterranean, and thence eastwards across Siberia, Turkey, Iran, and Central Asia to Alaska and north-western Canada, and also in Greenland and extreme north-eastern Canada.

The strange thing is that the entire population winters in Africa south of the Sahara. This means that birds from Greenland and eastern Canada cross the Atlantic, a distance of about 3,000 km. Birds from western Canada and Alaska fly all the way across Asia. One should think that evolution had caused some populations to choose other wintering areas, but this is not the case.

Excreta of northern wheatear, Karums Alvar, Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Phalacrocoracidae Cormorants

Cormorants and shags are a cosmopolitan family of c. 42 species of small to medium-sized, fish-eating birds. Some taxonomists divide these birds into three genera: 22 species of mainly larger birds in the genus Phalacrocorax, 15 species of mainly medium-sized birds in the genus Leucocarbo, and 5 species of small birds in the genus Microcarbo. However, the number of genera is often disputed.

A number of cormorant species are described on the pages Animals – Birds: Birds in Africa, Birds in the United States and Canada, and Fishing.

Phalacrocorax carbo Great cormorant

During the 1800s, this bird was persecuted all over Europe, partly because it was competing with fishermen, partly because its guano destroyed the trees, in which it was breeding. From about 1970, it was protected in many countries and has since then made a dramatic comeback. Today, it is very common in Europe.

The generic name is derived from the Greek phalakros (‘bald’) and korax (‘raven’), whereas the specific name is Latin, meaning ‘coal’, thus ‘the coal-black, bald raven’. The word ‘bald’ refers to the white crown of the great cormorant during the breeding season. However, as the crown is feathered, the name is rather misleading. The word ‘raven’ presumably refers to its otherwise black plumage.

Cormorant guano is caustic, and most of the plants that grow beneath a cormorant colony, will perish. These ramsons (Allium ursinum) in Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark, have been covered by a moderate layer of dung and may be able to survive. Ramsons is described on the page Nature: Invasive species. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This tree near Les Grangettes, Geneva Lake, Switzerland, which serves as a night roost for wintering great cormorants, is completely covered in guano. A highway is seen in the background. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Phasianidae Pheasants and allies

This family, containing about 190 species, includes pheasants, partridges, junglefowl, Old World quails, peafowl, grouse, and many others. These birds are found worldwide, except in Antarctica.

According to the latest genetic research, guineafowl and New World quails are treated as separate families, Numididae and Odontophoridae, respectively.

Alectoris chukar Chukar

This small gamebird is closely related to the European rock partridge (A. graeca). It is distributed from Turkey and Egypt eastwards across the Middle East to Central Asia, and it has also been introduced as a hunting object to many other areas, forming feral populations in several countries, including the United States and New Zealand.

This confiding chukar was photographed in a camp ground in Capitol Reef National Monument, Utah, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chukar tracks in a sandy area, Ulley Topko, Ladakh, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lophophorus impejanus Himalayan monal

This gorgeous gamebird, which is sometimes called Impeyan pheasant, is distributed from Afghanistan eastwards along the Himalaya to Bhutan. It is the national bird of Nepal, locally called danphe, and often referred to as ’the bird of nine colours’. In sunshine, the brilliant plumage of the male is glittering in almost all imaginable colours. The female is brownish and heavily streaked, with naked blue skin around the eyes and a pale patch on the throat.

It is also the state bird of Uttarakhand, northern India.

The specific name commemorates Lady Mary Impey, wife of Sir Elijah Impey (1732-1809), who was chief justice of the Supreme Court at Fort William, the first settlement of the British East India Company in Bengal.

As with most other gamebirds, the meat of monal is delicious, and for this reason it is hunted in many places. However, it is still common locally, and in the Khumbu area of eastern Nepal it is very common, as the local Buddhist Sherpas are against killing. So even though the monal does some damage by digging up potatoes and eating them, they are not persecuted here.

Male Himalayan monal, surveying his territory from a rock, Khumbu, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tracks of Himalayan monal in snow, Dodi Tal, Uttarakhand, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Phylloscopidae Leaf-warblers

In former days, members of this family were placed in the large warbler family (Sylviidae). However, genetic studies have had the effect that this family has been split into a number of families.

Leaf-warblers are about 80 species of small insectivorous birds, all belonging to the genus Phylloscopus. Previously, the family included the genus Seicercus, but recent genetic studies concluded that members of this genus should be moved to Phylloscopus.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek phyllon (‘leaf’) and skopos, from skopeo (‘to watch’), in this connection presumably meaning ‘to search’ (for insects).

Phylloscopus collybita Chiffchaff

This small warbler breeds in most of northern and central Europe, eastwards across the Siberian taiga, almost to the Pacific, and also in northern Tyrkey, the Caucasus, and northern Iran, wintering around the Mediterranean, in the Sahel zone of Africa, and from Syria eastwards to northern India.

The common name alludes to the song of the bird, a plaintive chiff-chaff.

This chiffchaff nest was built in an unusual place, in a bush about 50 cm above the ground. Usually, the nest is placed on or very near the ground. – Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Picidae Woodpeckers

Members of this family, comprising about 240 species in 35 genera, are found worldwide, except for Australia, New Guinea, New Zealand, Madagascar, and polar regions. Most species are known for their characteristic way of foraging, pecking on tree trunks and branches. Many species communicate by drumming with their beak on a tree trunk.

Plundered ant hills of Formica rufa, presumably the work of either green woodpecker (Picus viridis) or black woodpecker (Dryocopus martius), Gludsted Plantation (top) and Store Hjøllund Plantation, both central Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dead spruce, processed by a woodpecker, presumably black woodpecker, Gludsted Plantation. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spruce stumps, processed by woodpeckers, presumably great spotted woodpecker (Dendrocopos major) or black woodpecker, Store Hjøllund Plantation (top), and Gludsted Plantation. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dendrocopos hyperythrus Rufous-bellied woodpecker

This species is found from northern Pakistan eastwards along the Himalaya to China and Southeast Asia.

Due to its habit of drilling holes in the bark of trees to extract the sap, it was previously believed that this bird was related to the North American sapsuckers, genus Sphyrapicus, which have a similar way of feeding. The rufous-bellied woodpecker, however, is a genuine Dendrocopos species, and the similar habits are an example of convergent evolution.

At some point, a rufous-bellied woodpecker has drilled numerous holes into the trunk of this staggerbush (Lyonia ovalifolia), which has since shed its bark. – Asi Ganga Valley, Uttarakhand, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dendrocopos major Great spotted woodpecker

This species is widely distributed, found from northern Sweden, Finland, and Russia southwards to north-western Africa, the Caucasus, and the Alborz Mountains of Iran, and from the British Isles eastwards to Kamchatka, Japan, and China.

Most populations are resident, but the northernmost birds are migratory. Some birds stray far from the usual distribution area, sometimes as far away as North America.

Portrait of a great spotted woodpecker, Rømø, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spruce stump, processed by a feeding great spotted woodpecker, central Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

‘Workshop’ of a great spotted woodpecker on the trunk of an old apple tree, Funen, Denmark. The bird has placed a hazel nut in a crack and opened it. Note the frayed bark, a result of former usage of this tree by the bird. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spruce cones have been attached to cracks in this crumbling birch by a great spotted woodpecker, whereupon the bird has extracted the seeds. – Tofte Sø, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dryocopus martius Black woodpecker

This large species is distributed from Spain, France, and Scandinavia eastwards across the taiga zone to Kamchatka, Japan, and China, with isolated occurrence in the Caucasus and the Alborz Mountains in Iran.

Pine trees, worked on by black woodpeckers, Småland, Sweden. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dryocopus pileatus Pileated woodpecker

A close relative of the black woodpecker, found across southern Canada and the eastern half of the United States, southwards to Texas and Florida, and also in the Pacific States, southwards to California.

The term pileated refers to the prominent red crest of this bird, from the Latin pilleus (‘cap’) and atus (‘like’), thus ‘with a cap-like (crest)’.

Male pileated woodpecker, feeding on the ground, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Tennessee. The female has a black moustachial stripe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

American beech (Fagus grandifolia) with a nesting hole of pileated woodpecker, Kenoza Lake, Haverhill, Massachusetts. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Feeding marks of a pileated woodpecker on an old tree trunk, Eagle Lake, Acadia National Park, Maine. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Melanerpes formicivorus Acorn woodpecker

This bird is common from California southwards through Mexico and Central America to northern Columbia. As its name implies, its most important food item is acorns. It has an interesting habit of storing acorns as a winter supply in small holes, which the bird chisels into the bark of living or dead trees.

This acorn woodpecker has chiseled its nesting hole in the trunk of a palm tree in Santa Rosa Plateau Ecological Reserve, California, and around the nesting hole, it has made numerous small holes for storage of acorns. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Turdidae Thrushes

Thrushes constitute a large, almost global family of small to medium-sized birds, which spend much time feeding on the ground for worms and other invertebrates, and many species also eat fruit. Previously, this family was much larger, including many genera which are today included in the Old World flycatcher family (Muscicapidae).

The word thrush is derived from Old English throstle, from Proto-Germanic þrustlō, an ancient name for the song thrush (Turdus philomelos). In Old Saxon, þrustlō became throsla, in German Drossel. The latter name was adopted by the Danes, whereas the Swedes use the name trast for these birds, and the Norwegians trost.

Turdus merula Blackbird

The blackbird is described on the page Animals – Birds: Thrushes.

A blackbird has been eating from this apple, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Turdus pilaris Fieldfare

This large thrush breeds in scrubland and open forests, from northern Norway southwards to France, Switzerland, northern Italy, northern Slovenia, and northern Ukraine, and from eastern France eastwards across the entire taiga zone to eastern Siberia, Mongolia, and northern China. In England, it is a scarce breeding bird.

Populations of Scandinavia and Siberia are migratory, spending the winter in the British Isles, southern Europe, northern Africa, the Middle East, and areas around the Caspian Sea.

The name fieldfare is derived from the 11th Century word feldefare, which, according to some authorities, means ‘traveller across the fields’. However, in a paper from 1855, On False Etymologies, in Transactions of the Philological Society (6): 69, H. Wedgwood points out that this is a false presumption. In reality, the name is derived from the old Anglo-Saxon name of the bird, feala-for, perhaps alluding to the tawny-yellow colour on the breast.

During a period of severe frost, this small spring in Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark, serves as drinking place for fieldfares. The birds have left piles of reddish dung, the colour stemming from rose hips. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Unidentified birds

Tracks from an unidentified wader in sand, Maspalomas, Gran Canaria. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Reptiles

Cheloniidae Sea turtles

Of the world’s 8 species of sea turtles, 7 belong to this family. The eighth species is the huge leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), which forms a separate family, Dermochelyidae.

Although sea turtles spend about 98% of their life swimming about in the oceans, the females must get ashore, when they are about to lay eggs. With a great effort, they crawl ashore on a sandy beach, above the high tide line, where they dig a hole with their hind flippers.

When a female has finished digging, she lays a number of white eggs, often between 80 and 100. They resemble table tennis balls in shape, but are soft, so that they do not break when they fall into the hole. When the egg-laying is over, the female covers the eggs, throwing sand about with her flippers to camouflage the spot. Then she returns to the sea.

Some sea turtle species lay eggs several times in a season, in some cases up to 11 clutches.

Although a sea turtle will camouflage the egg-laying spot with sand, it is revealed by her characteristic ‘tractor’ tracks, in this case on Latham Island, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lepidochelys olivacea Olive ridley

This rather small species, growing to about 75 cm long, is the most abundant of all sea turtles. It occurs in all warmer seas, primarily in the Pacific and Indian Oceans. It is known for its spectacular synchronised mass nesting, called arribada (Spanish for ‘arrival’), where thousands of females gather on the same beach to lay eggs. Two of these places are Playa Ostional, Guanacaste Province, Costa Rica, and Odisha, eastern India.

The specific name alludes to the olive tinge on this otherwise brownish or greyish animal.

My experience with this animal is related on the page Animals – Reptiles and amphibians: Reptiles and amphibians in the Indian Subcontinent.

Egg-laying olive ridley, Hikkaduwa, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tracks from an egg-laying olive ridley, Hambantota, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Varanidae Monitor lizards

This family is a group of about 80 species of large, carnivorous and frugivorous lizards of the genus Varanus, native to Africa, Asia, and Australia. It includes the largest living lizard, the Komodo dragon (V. komodoensis), which is described on the page Travel episodes – Indonesia 1985: Difficult journey to Komodo.

The generic name is of Semitic origin, meaning ‘dragon’ or ‘lizard beast’. The English name is explained in various ways. Some say it has its origin due to the occasional habit of these animals to stand on their two hind legs, seemingly ‘monitoring’ something. Others say that it arose from an old superstitious belief that they would warn people of the approach of venomous animals.

Varanus salvator Water monitor lizard

As its name implies, this large lizard, growing to about 2 m long, lives close to wet habitats. It is native from Sri Lanka and coastal north-eastern India eastwards to Southeast Asia and thence southwards to the Indonesian archipelago. Usually, people chase these animals away, as they are notorious plunderers of chicken yards, but where left in peace, they often become confiding.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘saviour’. Its origin is unexplained, but possibly indicates a religious connection.

Tracks of water monitor lizard on a sandy beach, Pulau Kapas, Malaysia. The tip of the tail has been dragged along the ground. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Invertebrates

Andrenidae Mining bees

A large, nearly cosmopolitan family of solitary, ground-nesting bees, most members living in temperate or arid areas. It contains some very large genera, including Andrena (below) and Perdita (more than 700 species).

Andrena

A huge genus of mining bees with about 1,500 species, distributed across the globe, with the exception of South America, the Pacific region, and polar areas.

These bees differ from honey bees by digging nests in loose sand or gravel in sunny locations, e.g. on sandy roads or in heaths. They often breed many together, but each female digs her own nest, where she lays eggs, and then collects food for the larvae herself.

Breeding holes of mining bees, Öland, Sweden. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Brachyura Crabs

These tiny sand balls on a beach near Tongxiao, western Taiwan, have been left here by small crabs, which have cleaned their dens after high tide. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

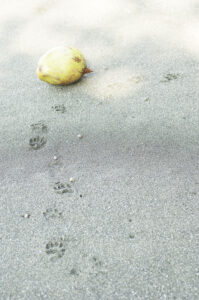

Tracks of numerous hermit crabs create patterns around a fallen fruit on a sandy beach, Corcovado National Park, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cicadiodeae Cicadas

Empty pupae cocoons of cicadas, Chingshuian Recreation Area, central Taiwan. The one in the lower picture has been infested by a fungus. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Coleoptera Beetles

In Ancient Egypt, Khepri was a solar deity, connected with the dung beetle, or scarab beetle (Scarabaeus sacer). These beetles were sacred, because they would roll balls of dung across the ground – an act that the Egyptians saw as a symbol of the forces, which move the sun across the sky. Dung beetles became very popular as amulets and impression seals, called scarab, and they were often depicted on temples, graves etc.

In Africa, dung beetles are very common, often seen on various types of dung, which they form into balls, rolling them away to bury them and lay eggs in them.

As a boy, the famous naturalist and conservationist Gerald Durrell (1925-1995) was much intrigued by these beetles. His amusing account is related on the page Quotes on Nature.

This dung beetle is forming a ball of elephant dung, after which it will roll it away, bury it and lay eggs in it. – Meru National Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Scarab beetles, making balls of zebra dung, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This dung, presumably also from a zebra, has attracted scarab beetles and a single green beetle, Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tortoise beetles, subfamily Cassidinae, are a large group of more than 3,000 beetle species, which resemble miniature turtles due to the forward and sideways extensions of their body. They measure between 5 and 12 mm in length, and the larvae are spiny. Both adults and larvae eat leaves, and some species are regarded as agricultural pests.

One genus in the subfamily is Cassida, containing more than 430 species, distributed in the Old World. The generic name is derived from the Latin cassis (‘metal helmet’).

The Japanese turtle beetle (Cassida japana) is distributed in Japan, China, Taiwan, and Indochina.

This leaf of an Achyranthes species, observed in Malabang National Forest, Taiwan, has been partly eaten by Japanese turtle beetles, one of which is sitting on the leaf. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In the Alps and other montane areas of central Europe, you often come across a growth of common adenostyles (Adenostyles alliariae), whose leaves have been almost completely eaten by larvae of Oreina cacaliae, a metallic, bluish or greenish beetle, which belongs to the family broad-shouldered leaf beetles (Chrysomelidae). This species is partial to common adenostyles, as well as alpine butterbur (Petasites paradoxus).

These leaves of common adenostyles in the Grossglockner area, Austria, have been almost completely eaten by larvae of Oreina cacaliae. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The great capricorn beetle (Cerambyx cerdo), of the family Cerambycidae, is widespread in central and southern Europe, from Spain and France eastwards to Belarus, Ukraine, and Turkey. There is also a small, declining population on the Swedish island Öland.

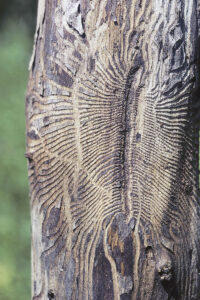

Feeding tunnels of larvae of the great capricorn beetle criss-cross the trunk of this dead common oak (Quercus robur), Halltorps Hage, Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

There are about 6,000 species of bark beetles in c. 220 genera, belonging to the subfamily Scolytinae, of the family Curculionidae.

Feeding tunnels, made by larvae of the ash bark-beetle (Hylesinus fraxini), branching out from the mother-beetle’s egg-laying tunnel on the trunk of an ash (Fraxinus excelsior), Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Egg-laying females of elm bark beetles (Scolytus) often transmit spores of the Dutch elm disease fungus Ophiostoma to elm trees (Ulmus). This disease is described on the page Nature Reserve Vorsø: Dutch elm disease on Vorsø.

Branches of common elm (Ulmus glabra) with feeding tunnels of elm bark beetle larvae, branching out from the mother-beetle’s egg-laying tunnel. The tree has since died from Dutch elm disease. – Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)