Deer

Mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), feeding in grassland, Salt Point State Park, California, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), feeding on lush vegetation of red goosefoot (Oxybasis rubra), Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sambar deer stag (Cervus unicolor), Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Resting wapiti stag (Cervus canadensis), Fort Niobrara Wildlife Refuge, Nebraska, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spotted deer stag (Axis axis), drinking from a waterhole in Sariska National Park, Rajasthan, India. A rufous treepie (Dendrocitta vagabunda) is sitting on its back. To the left a peacock (Pavo cristatus). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Deer are a group of ruminants, constituting the family Cervidae, which contains 20 genera with about 90 species. They are believed to have evolved from tiny, rabbit-sized, tusked ancestors, without antlers, which lived about 50 million years ago.

Gradually, they developed into the first antlered, deer-like animals about 20 million years ago, and eventually, with the development of antlers, the tusks disappeared, except in a single species, the water deer (Hydropotes inermis), which, in this respect, resembles the unrelated musk deer (Moschidae). Genus Muntiacus (described below) has retained the tusks, but also has small antlers.

Deer live in almost all types of habitats, ranging from tundra to tropical rainforest. They are widely distributed, with native species present in all continents, except Antarctica and Australia. The largest concentration of species is found in Asia.

In Africa, antelope have replaced deer in almost the entire continent, with the exception of the Atlas Mountains in the north-western corner, where the native Barbary stag, a subspecies of red deer (Cervus elaphus) is found. Fallow deer (Dama dama) have been introduced to South Africa.

The antlers are shed every year. In this respect, deer differ from the permanently horned ruminants of the family Bovidae (cattle, sheep, goat, antelope, and goat-antelope). Only males have antlers, with the exception of female reindeer, or caribou (Rangifer tarandus). During the rut, when females are in oestrus, males use the antlers to fight for dominance, i.e. the right to mate with the females.

When the mating season is over, the antlers are shed, leaving only two small knobs, called pedicles. While new antlers emerge, they are covered by a layer of short-haired skin, called velvet. Once they cease growing, the velvet dies, creating an intense itching. To relieve this itching, the deer brushes the antlers against bushes or young trees, causing the velvet to loosen and fall off. This behaviour is called fraying. This fraying is often so violent that the bark of younger trees is removed all the way around the trunk, and the plant dies.

In many deer species, which live in cold climates, the summer pelt is reddish-brown, whereas the winter pelt is greyish.

A larger deer male is called a stag, a female a hind, and a young a kid or a calf. An exception is the huge moose (Alces alces), where a male is a bull, a female a cow. A smaller deer male is called a buck, a female a doe, a young a fawn. A group of deer is a herd.

Although deer-like, musk deer (Moschidae) and chevrotains, or mouse-deer (Tragulidae), constitute separate families of ruminants, which are not closely related to true deer. Musk deer are described in depth on the page Animals – Mammals: Mammals of the Indian Subcontinent.

Resting spotted deer stag (Axis axis) with antlers in velvet, Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sparring barasingha stags (Rucervus duvaucelii ssp. branderi), Kanha National Park, Madhya Pradesh, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stag of eastern swamp deer (Rucervus duvaucelii ssp. ranjitsinhi) in evening light, Kaziranga National Park, Assam, eastern India. His antlers have been shed, leaving only two small knobs, the pedicles. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A selection of antlers, shed by roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sycamore maples (Acer pseudoplatanus), Nature Reserve Vorsø. One has been killed by a fraying roe buck. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The trunk of this young wild cherry (Prunus avium) has a partly healed wound, after being frayed by a roe buck, Nature Reserve Vorsø. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Classification

A genetic study from 2006 concludes that Cervidae consists of two subfamilies.

Cervinae, or Old World deer, has two tribes, Cervini, comprising the genera Cervus, Dama, Axis, Hyelaphus, and Rucervus; and Muntiacini, comprising the genera Muntiacus and Elaphodus.

Capreolinae, or New World deer, has three tribes, Capreolini, comprising the genera Capreolus and Hydropotes; Alceini, comprising the genus Alces; and Rangiferini, comprising the genera Rangifer, Odocoileus, Pudu, Blastocerus, Hippocamelus, and Mazama. (Source: C. Gilbert, A. Ropiquet & A. Hassanin 2006. Mitochondrial and nuclear phylogenies of Cervidae (Mammalia, Ruminantia): Systematics, morphology, and biogeography. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 40 (1): 101-17)

Selected species

Below, a collection of pictures depict deer species that I have managed to photograph around the world.

Subfamily Cervinae, tribe Cervini

Axis

Previously, the hog deer (Hyelaphus porcinus) and three other small deer were placed in this genus. However, genetic studies have revealed that they differ sufficiently from the spotted deer (below) to constitute a separate genus, leaving the latter as the only member of the genus Axis.

Axis axis Spotted deer, chital

This beautiful deer is native to the Indian Subcontinent, including Sri Lanka, but is found nowhere else. It is fairly common in most of the distribution area, though declining in places due to habitat destruction. It has been introduced elsewhere, including Australia, United States, and several South American countries.

A medium-sized deer, males may weigh up to 100 kg, whereas the females are much lighter.

The generic and specific names are Latin, referring to an Indian animal, mentioned by Roman philosopher and naturalist Pliny the Elder (c. 23-79 A.D.). The Hindi name chital is derived from Sanskrit citrala (‘spotted’).

On a baking hot summer day, spotted deer quench their thirst in a waterhole, Sariska National Park, Rajasthan. The palms in the background are Indian date palms (Phoenix sylvestris). A peahen (Pavo cristatus) is seen in the lower picture. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This hind with a kid is raising her tail as an alarm signal, Sariska National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

When approaching these spotted deer in Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, Tamil Nadu, I stepped on a dead branch. The sound immediately made them raise their heads and stare in my direction. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spotted deer in grassland, Corbett National Park, Uttarakhand. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

We found this abandoned kid in the grassland of Corbett National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This stag was killed by a tiger or a leopard, but was left due to heavy rain, Corbett National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cervus

Genetic research indicates that this genus evolved in Central Asia, where an ancient species, now named Cervus hanglu, still exists, with 3 subspecies, the Kashmir stag (below), the Bactrian deer, ssp. bactrianus, which is widespread in Central Asia, and the Yarkand deer, ssp. yarkandensis, which is restricted to Xinjiang. About 7 million years ago, the climate became cooler, causing this ancestral deer to migrate north, east, and west.

Today, the western Eurasian group, called red deer (C. elaphus, see below), has several subspecies in western Europe, the Balkans, the Middle East, and North Africa. However, the taxonomy of this group remains unsettled, and some subspecies may merit specific status, including C. (e.) corsicanus, which lives on Corsica and Sardinia. It may be conspecific with the Barbary stag (C. (e.) barbarus) of north-western Africa.

The eastern Eurasian group includes the wapiti (below), which is distributed in north-eastern Asia and North America, Thorold’s or white-lipped deer (C. albirostris), which occurs in eastern Tibet, Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan, and north-western Yunnan, and the sika deer (below), which is found in Japan and Taiwan, at scattered locations in eastern China, and in Ussuriland, south-eastern Siberia.

Some authorities place several South Asian deer in the genus Cervus, others in the genus Rusa, including the sambar deer (below) and the rusa deer (below).

The generic name is the classical Latin term for deer.

Cervus canadensis Wapiti, American elk

This is one of the largest deer species, stags weighing 320-330 kg, hinds 225-240 kg. It is also one of the largest mammals within its distribution area, which encompasses north-eastern Asia and North America. It has been introduced elsewhere, including Argentina and New Zealand.

To the early European explorers in North America, this animal resembled a moose (below), and, consequently, they gave it the name elk, which is the European English name for the moose, derived from Old Norse elgr. The name wapiti is a Shawnee and Cree word, meaning ‘white rump’. The Altai wapiti of Central Asia (C. c. sibiricus) is locally known as the Altai maral.

Grazing wapitis, Fort Niobrara Wildlife Refuge, Nebraska, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

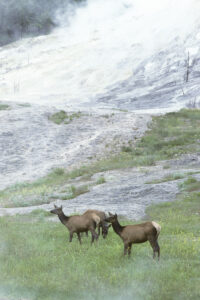

Wapitis, grazing near Minerva Springs, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, United States. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grazing wapiti stag, his antlers in velvet, Fern Canyon, Redwood National Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grazing wapiti hind, Sinkyone Wilderness State Park, California. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cervus elaphus Red deer

A large deer, the stag typically weighing 160-240 kg, the hind 120-170 kg. It is native to the major part of Europe, north-western Africa, and Turkey, eastwards to southern Russia, the Caucasus, and northern Iran. It has also been introduced as a hunting object to other areas, including Australia, New Zealand, United States, Canada, and several South American countries. In New Zealand, it is very harmful to the environment, and eradication programs are carried out in several national parks.

At one time, the red deer was rare in parts of Europe, and had even been eradicated in some areas. Since then, conservation efforts, combined with reintroduction, has resulted in growing populations in several countries, including England, Portugal, and Denmark. In other areas, the species is declining, including in North Africa.

The specific name is a Latinized version of elaphos, the classical Greek term for deer.

Resting red deer stag, Jægersborg Deer Park, Zealand, Denmark. In the 1600s, red deer and fallow deer (below) were introduced to this park as hunting objects for the king and his retinue. Today, about 300 red deer and 1,600 fallow deer live here. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red deer, bred in captivity, Jubilee Park, Ohakune, New Zealand. The birds in front of the deer are paradise shelduck (Tadorna variegata). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cervus hanglu ssp. hanglu Kashmir stag

Traditionally, this deer was regarded as a subspecies of C. elaphus. However, recent genetic studies have concluded that it belongs to an ancient lineage (see genus above).

It is restricted to a few locations in Kashmir and northern Himachal Pradesh. Habitat destruction, competition from grazing livestock, and poaching brought it to the brink of extinction, with only about 150 individuals surviving around 1970. Conservation measures has had the effect that the population is now around 300, but this number is still dangerously low.

The specific name is a corruption of hangul, the local Kashmir name of this deer.

According to the Indian Hindu epic Mahabharata, one of the Pandava brothers, Bhima, spent some time in exile in Manali, Himachal Pradesh, northern India. During his stay, he fell in love with a local beauty, Hadimba (also called Hidimbi), who, as a young woman, had vowed to marry the man, who was able to defeat her brother Hadimb (or Hidimb) – a very brave and strong person.

Bhima managed to kill Hadimb, whereupon Hadimba married him. Later, the local people regarded her as a goddess, an incarnation of the supreme Mother Goddess Devi.

The Hadimba Temple in Manali was erected in 1553 over a cave in a huge rock, where Hadimba supposedly meditated. Later, this rock was worshipped as an image of the deity.

The Pandava brothers are described in depth on the page Religion: Hinduism.

The Hadimba Temple is adorned with antlers of Kashmir stag, and horns of various other animals, including bharal (Pseudois nayaur) with smooth horns and Siberian ibex (Capra sibirica) with ringed horns. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cervus nippon Sika deer

The name of this smallish deer is derived from shika (鹿), meaning ‘deer’ in Japanese. Comprising about 13 subspecies, it is distributed in East Asia, from Ussuriland in south-eastern Siberia southwards through most of China, Korea, Japan, and Taiwan to northern Vietnam. A population on Jolo Island, Philippines, is tentatively regarded as subspecies soloensis. It was originally introduced and has possibly become extinct. The species is threatened in the wild everywhere in its distribution area, with the exception of Japan, where it is abundant.

Sika deer have been introduced to many countries around the world, and in some places they have escaped to form feral populations. This is the case in the Scottish Highlands, where they hybridize with native red deer, thus being a serious threat to the gene pool of the red deer population.

The specific name is taken from Nippon, the Japanese term for Japan.

Sika deer stags, Jægersborg Deer Park, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cervus timorensis Rusa deer

This medium-sized deer, by some authorities named Rusa timorensis, is native to a number of Indonesian islands, from western Java eastwards to Timor, and on Sulawesi, the Moluccan Islands, and Seram. It has also been introduced elsewhere, including Australia, New Zealand, and many Melanesian and Pacific islands.

The specific name refers to the island of Timor. Presumably, the type specimen was collected there.

On the island of Komodo, this deer constitutes an important food item for the Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis). This huge lizard waits patiently at a waterhole, and when a potential prey approaches to quench its thirst, the dragon suddenly rushes forward, biting a leg of the animal. Then all it has to do is to follow the scent trail of the victim. The saliva of Komodo dragons is toxic, and after some hours the prey is so weak that the lizard is able to kill it.

My encounter with these monsters is related on the page Travel episodes – Indonesia 1985: Difficult journey to Komodo.

Rusa deer hind, Komodo Island, Indonesia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cervus unicolor Sambar deer

This very large deer, by some authorities named Rusa unicolor, has a wide distribution in Asia, from the entire Indian Subcontinent eastwards to southern China and Taiwan, and thence southwards through Indochina and Malaysia to Sumatra and Borneo.

The weight of a stag is typically around 350 kg, although large specimens may weigh as much as 550 kg. Hinds are smaller, weighing 100-200 kg. Populations of this deer have declined substantially in most areas, mainly due to hunting and habitat destruction. It has been introduced to various countries around the world, including Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.

The common name is derived from Sanskrit sambara (‘deer’).

Sambar stags, one with the antlers in velvet, Maha Eliya Thenna (Horton Plains) National Park, Sri Lanka. The subspecies unicolor, found in India and Sri Lanka, is the largest of the seven accepted subspecies. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This stag, observed in Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan, has had a close encounter with a tiger or a leopard, evident from the scar on the flank. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sambar deer ofte feed in the lakes of Ranthambhor National Park. This herd is resting in front of ruins of a former Rajput palace. The fierce Rajputs are described on the page Travel episodes – India 1986: “His name is Muhammad!” (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sambar hind, grazing on succulent water plants in a lake, Ranthambhor National Park. A grey heron (Ardea cinerea) is using its back as a lookout post. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sambar stag, drinking from a lake, Ranthambhor National Park. It is raising its tail as an alarm signal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sambar deer in morning light, Sariska National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hind in evening sun, Sariska National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Portrait of a hind, which is much bothered by flies, Ranthambhor National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This hind is feeding in a swamp in Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. Painted storks (Mycteria leucocephala) are nesting in the tree in the background. One of the storks is spreading its wings like two large fans. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A hind and her calf quenches their thirst at a waterhole, Sariska National Park. The monkeys to the right are northern plains langurs (Semnopithecus entellus). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A rufous treepie (Dendrocitta vagabunda) is using the back of this hind as a lookout post, Sariska National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Drinking hinds, Sariska National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On a hot September day, this hind is cooling down in a waterhole, Sariska National Park. Peafowl (Pavo cristatus) are seen in the background. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stag, enjoying a bath, Sariska National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sambar calf, gazing at its reflection in a lake, Ranthambhor National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Suckling calf, Ranthambhor National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dama

This genus contains one or two species, the European fallow deer (below) and the Persian fallow deer (Dama mesopotamica or Dama dama ssp. mesopotamica). Most taxonomists regard it as a separate species, as it is larger, with larger antlers. This animal is nearly extinct today, with tiny populations in Khuzestan, southern Iran, Mazandaran, northern Iran, on an island in Lake Urmia in north-western Iran, in northern Israel, and possibly a few places in Iraq.

The generic name is the classical Latin term for the fallow deer.

Dama dama Fallow deer

During the last interglacial period, the fallow deer was native to the major part of Europe, but retreated due to the advancing glaciers and became restricted to the Middle East, replaced further east in Asia by the Persian fallow deer (see above).

At an early stage, the fallow deer was reintroduced to deer parks all over Europe, and recently it has also been introduced to many other countries, including Australia, New Zealand, Argentina, and the United States. It often forms feral populations.

Fallow deer, seen as silhouettes, Jægersborg Deer Park, Zealand, Denmark. In the 1600s, fallow deer and red deer (above) were introduced to this park as hunting objects for the king and his retinue. Today, about 1,600 fallow deer and 300 red deer live here. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In the 1200s, the island of Romsø, near Funen, Denmark, was the property of the king. He introduced fallow deer from Turkey and released them on this island as a hunting object. On this island, there were no wolves to prey on the deer, which was the case in most areas of Denmark in those days. Today, a large herd of fallow deer are roaming the island, which is a private reserve.

Fallow deer, Romsø. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hyelaphus

Previously, the Indian hog deer (below) and three other small Asian deer were placed in the genus Axis (above). However, genetic studies have revealed that they differ sufficiently from the spotted deer (above) to constitute a separate genus.

I have not been able to find an explanation regarding the etymology of the generic name. The last part is a Latinized version of Ancient Greek elaphos (‘deer’), and the first part may be derived from Ancient Greek hyle (‘forest’).

Hyelaphus porcinus Indian hog deer

A small deer, the buck standing about 70 cm at the shoulder and weighing about 50 kg. The doe is much smaller, standing about 60 cm and weighing c. 30 kg.

It ranges from Pakistan in a belt eastwards across the Gangetic Plain of northern India to Bangladesh and Myanmar. It has also been introduced to Australia and Sri Lanka. In Indochina and south-western China, it is replaced by the Indochinese hog deer (H. annamiticus).

The specific name, from Ancient Greek porkos (‘pig’ or ‘hog’), was given in allusion to the hog-like manner, in which it runs through the forest, with the head stretched forward, so that it can duck under obstacles instead of leaping over them.

Hog deer and a single spotted deer (see above), eating soil to obtain minerals, Rapti River, southern Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hog deer buck, his antlers in velvet, Rapti River. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hog deer does, Kaziranga National Park, Assam (top), and Corbett National Park, Uttarakhand. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hog deer, drinking from a rainwater puddle, Corbett National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rucervus

This genus is an ancient lineage that, together with the genus Axis (above), represents the oldest radiation in the subfamily Cervinae. It was originally proposed as a subgenus of Cervus by British naturalist and ethnologist Brian Hodgson (1801-1894), based on antler shape. Today, the genus has a single member, the barasingha (below), as the only other member, Schomburgk’s deer (R. schomburgki) of Indochina, is probably extinct.

The generic name is a combination of two other genus names, Rusa, which means ‘deer’ in Malay, and Cervus (above).

Rucervus duvaucelii Barasingha, swamp deer

In the 1800s, this species ranged from Pakistan eastwards across northern and central India and southern Nepal to Bangladesh and north-eastern India. However, due to uncontrolled hunting and habitat loss, the population is today highly fragmented, with scattered herds found in southern Nepal and in Uttar Pradesh, Assam, and Madhya Pradesh. It is extinct in Pakistan and Bangladesh.

This deer differs from all other Indian species in that the antlers carry more than 3 tines, giving rise to the Hindi name barah singga, meaning ‘twelve-horned’. Mature stags usually have 10-14 tines, but up to 20 has been recorded.

Three subspecies have been described. The western nominate race has splayed hooves, an adaptation to live in flooded grasslands in the Indo-Gangetic plain. Today, a population of about 2,000 live in scattered locations in Uttar Pradesh, and about 2,200 in the Sukla Phanta Wildlife Reserve in western Nepal.

The eastern subspecies ranjitsinhi is restricted to the north-eastern state of Assam, where the population was as low as about 700 in 1978. Since then, numbers have been steadily rising due to conservation efforts. In 2016, it was estimated that about 1150 individuals were present in Kaziranga National Park. A few also live in Manas National Park and other protected areas.

The southern subspecies branderi differs from the other subspecies in having hard hooves, an adaptation to live in open forest with an understorey of grass. Formerly, it was restricted to Kanha National Park in Madhya Pradesh, where only about 750 individuals survive. Lately, it has been reintroduced to Satpura Tiger Reserve, likewise in Madhya Pradesh.

The specific name commemorates French naturalist and explorer Alfred Duvaucel (1793-1824), who died in India, only 31 years old. Rumours had it that he was killed by a tiger.

Barasingha stags, subspecies branderi, in morning light, Kanha National Park, Madhya Pradesh. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Barasingha stags, Kanha National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Barasingha stags in evening light, Kanha National Park. The bird is a black drongo (Dicrurus macrocercus). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Barasingha hind in evening light, Kanha National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Herd of eastern swamp deer, ssp. ranjitsinhi, Kaziranga National Park, Assam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hind and calf, Kaziranga National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Cervinae, tribe Muntiacini

Muntiacus Muntjac, barking deer

This genus of small deer, comprising 12 species, is native to Asia, occurring from India and Sri Lanka eastwards to southern China and Taiwan, and thence southwards to the Indonesian Archipelago. They are thought to have originated in Europe 15-35 million years ago. Several species are threatened, and one, the giant muntjac (M. vuquangensis) of Indochina, which was described as late as 1994, is critically endangered.

Males are characterized by their short antlers, often only about 10 cm long. Instead of using their antlers, they tend to fight for territory with their 2-4 cm long upper canines. Where the males have antlers, the females have small bony knobs with tufts of fur.

The generic name is a Latinized form of the Dutch name of these animals, muntjak, which is a corruption of their Sundanese name, mencek. The popular name barking deer was given in allusion to their alarm call, which is reminiscent of a dog’s barking.

Muntiacus muntjak Indian muntjac

This very widespread animal, in Hindi known as kakar, is distributed from India and Sri Lanka eastwards to southern China, and thence southwards through Indochina and Malaysia to Java and Bali. 15 subspecies have been described. In the Himalaya, it is found up to elevations around 2,500 m.

Male Indian muntjac with antlers in velvet, between Sherpagaon and Surkhe, Lower Langtang Valley, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Indian muntjac doe in dense vegetation, Begnas Tal, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Does, Corbett National Park, Uttarakhand. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Indian muntjac in captivity, Melamchi Phul, Helambu, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Muntiacus reevesi Reeves’s muntjac, Chinese muntjac

This species is distributed in southern China and Taiwan. It was named in honour of English naturalist John Reeves (1774-1856), who was a tea inspector for the British East India Company. He developed a notable collection of Chinese drawings of animals and plants.

Reeves’s muntjac was introduced to Britain in the 1800s, and a steadily growing feral population has been established from zoo escapes. It is now found in most English counties and has expanded its range into Wales and southern Scotland. It has also been introduced to Japan, Holland, and Belgium.

Reeves’s muntjac is very common in Taiwan, where it was formerly a popular food item of the indigenous Malayan tribes. This picture shows a Bunun man, his head ornament adorned with muntjac antlers in velvet. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Capreolinae, tribe Capreolini

Capreolus capreolus Roe deer

This small deer is distributed all over Europe, with the exception of Ireland and far northern Scandinavia, Finland, and Russia. It is also found in Turkey, the Caucasus, and northern Iran.

From Ukraine and the northern flanks of the Caucasus, eastwards through the taiga zone to the Pacific Ocean, and also in Tibet, Korea, and Manchuria, this species is replaced by the Siberian roe deer (C. pygargus). Formerly, these deer were regarded as a single species, but today most authorities recognize them as separate species. The Siberian roe deer is larger, with longer, more branched antlers than the European roe deer.

In Roman Latin, the term capra, or caprea, usually indicates a billy goat, but with the diminutive suffix –olus added, it means ‘small deer’. The name pygargus stems from the Greek pygargos, from pyge (‘rump’) and argos (‘white’), alluding to the deer flashing the white hair on the rump when alarmed.

Roe buck and doe in the reddish summer coat, Møn, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Roe buck in the reddish summer coat, crossing a pond, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Doe in the reddish summer coat, Nature Reserve Vorsø. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Doe in the greyish-brown winter coat, feeding at the edge of a forest, Funen, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fawn, Nature Reserve Vorsø. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Capreolinae, tribe Alceini

Alces alces Moose, European elk

The only member of the genus, the moose is distributed across the entire taiga zone in the Northern Hemisphere, from Norway eastwards to eastern Siberia, and in Alaska, Canada, and northern United States. In Sweden and other places, it has adapted to other types of forest, and can also be encountered in open areas, such as fields.

The size of this huge deer varies considerably according to subspecies and also availability of nutritious food. On average, an adult bull measures 2 m at the shoulder, the cow 1.4 m. Bulls may weigh almost up to a ton, although 380-700 kg is more common. Cows typically weigh 200-490 kg. Besides his enormous antlers, the bull is characterized by a large dewlap. Seven subspecies are recognized.

The generic and specific names probably stem from Proto-Germanic algiz, which was corrupted to alke in Ancient Greek, and in Norse elgur, which was shortened to elg in Danish and Norwegian, älg in Swedish.

Their antlers interlocked in battle, these two bull moose were found near New Sweden, Maine, United States, in 2005. Presumably, they died of starvation. Today, they are on display in L.L. Bean Shopping Centre, Portland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Moose cow grooming, Halleberg, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In a dense forest on the island of Öland, Sweden, I stumbled on this newborn moose calf, which is struggling to get on its feet. The mother crashed into the undergrowth, when I approached, and, fearing that it would attack me, I hurriedly snapped this single photo and retreated. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In Denmark, the moose was eradicated by hunters, probably during the Bronze Age. The antlers below, excavated on the island of Bornholm, are from the Stone Age, displayed at the Museum of Bornholm. Several moose were reintroduced to Lille Vildmose, Jutland, in 2015-17, and the population is thriving.

(Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Capreolinae, tribe Rangiferini

Odocoileus

This small genus of medium-sized deer only has two members, native to the Americas. The generic name is derived from the Greek odous (‘tooth’) and koilos (‘hollow’), alluding to the fact that these deer have hollow teeth.

Odocoileus hemionus Mule deer, black-tailed deer

This deer is widespread and rather common in the western half of North America, from southern Alaska southwards to Baja California and central Mexico.

The name mule deer refers to its rather large ears, reflected in the specific name, from the Greek hemionos (‘mule’). The two names of this deer indicate the main differences between this species and the white-tailed deer (below).

Mule deer, Badlands National Park, South Dakota. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mule deer stags, Mariposa Grove, Yosemite National Park, Sierra Nevada, California. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mule deer hind and calf, Point Reyes National Seashore, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On a hot spring day, this mule deer hind is resting in the shade of a desert bush, Saguaro National Park, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Odocoileus virginianus White-tailed deer

One of the most widespread and common deer species in the world, found in the major part of North America, from southern Canada southwards, and in Mexico, Central America, and northern South America, southwards to Peru and Bolivia.

It has also been introduced elsewhere, including Cuba, Jamaica, New Zealand, Finland, and the Czech Republic. It is regarded as an invasive in Finland and New Zealand, and even in parts of its native United States. More about this issue is related on the page Nature: Invasive species.

This white-tailed deer hind, in its greyish winter pelt, is raising its tail as an alarm signal, Shenandoah National Park, Appalachian Mountains. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

White-tailed deer hind, in its reddish summer pelt, Everglades National Park, Florida. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grazing white-tailed deer hind, Cathlamet, Washington State. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rangifer tarandus Reindeer, caribou

You know Dasher and Dancer and Prancer and Vixen,

Comet and Cupid and Donner and Blitzen,

But do you recall

The most famous reindeer of all?

Rudolph, the red-nosed reindeer,

Had a very shiny nose,

And if you ever saw it,

You would even say it glows.

All of the other reindeer

Used to laugh and call him names,

They never let poor Rudolph

Join in any reindeer games.

Then one foggy Christmas Eve

Santa came to say:

“Rudolph, with your nose so bright,

Won’t you guide my sleigh tonight?”

Then how the reindeer loved him,

As they shouted out with glee:

“Rudolph, the red-nosed reindeer,

You’ll go down in history!”

Image borrowed from englishenglish.biz

Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer is a hugely popular Christmas song, written by American songwriter Johnny Marks (1909-1985), based on a story from 1939 with the same title, written by Robert L. May (1905-1976).

The belief among small children that Santa Claus’s sleigh is pulled by eight reindeer, when he brings gifts to them on Christmas Eve, actually has its root in the mythology of semi-nomadic Siberian reindeer herders.

As American author and ethnologist Robert Gordon Wasson (1898-1986) amply demonstrates in the classic Flesh of the Gods, one sacred ritual of ancient, pre-Christian Europe centered around a red mushroom, the fly agaric (Amanita muscaria). The powerful, mind-altering properties of this mushroom were so prized by shamans that it was hunted to extinction on the Indian subcontinent. It is hard to exaggerate the importance of this fungus to Western consciousness.

One group of Amanita users who, until the early 1900s, still practiced a late Ice Age lifestyle, were semi-nomadic reindeer herders of far northern Scandinavia and Russia, living in yurts and moving about in reindeer-drawn sleighs. Their shamans wore pointed red hats, symbolizing the mushroom that was their sacrament. The shamans also wore red capes, symbolizing their flight through the air, when they consumed the mushroom on their most sacred night of the year – the Winter Solstice (then December 25). Do you recognize the dress of Santa Claus?

The modern character of Santa was based on traditions surrounding Saint Nikolaos (c. 270-343), in English Nicholas, an early Christian bishop of Greek descent from the city of Myra, today called Demre, in the present-day Antalya Province of southern Turkey. Hence the name Santa Claus, a corruption of Nikolaos.

The reindeer, or caribou, as it is called in America, is the only member of the genus Rangifer. It has a circumpolar distribution, being a native of tundra and boreal areas of northern Europe, Siberia, Alaska, and Canada. This animal usually lives in large herds, of which some are sedentary, others migratory.

Caribou is an algonquin word, mening ‘shoveler’, referring to the way reindeer scrape in the snow to find food.

The Taimyr subspecies of Siberia, sibiricus, constitute the largest wild reindeer herd in the world, estimates varying between 400,000 and 1,000,000. What was once the second-largest herd, the George River herd in Canada, of the subspecies caribou, which was estimated at a maximum of 385,000 individuals, has dwindled to a tiny fraction of its former numbers, today counting fewer than 9,000 animals. A southern population of this subspecies, which lived in the contiguous United States, is virtually extinct.

In former days, wild reindeer were roaming over large parts of northern Europe. Climate change, combined with uncontrolled hunting, and also domestication of the animals, have caused the wild reindeer to become extinct in Europe, with the exception of southern Norway, where a total of c. 25,000 individuals live in 23 fragmented areas. A vast high plateau, called the Hardangervidda, harbours the largest population, 6,000-7,000.

Wild reindeer, Hardangervidda, southern Norway. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A large number of Vietnamese are Christians. On the occasion of the approaching Christmas, these bushes in a park in Hanoi, Vietnam, have been shaped to form reindeer. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

As its name implies, the reindeer lichen (Cladonia rangiferina) constitutes an important food item for reindeer. It is distributed in tundra and coniferous forests in arctic and northern temperate areas of the Northern Hemisphere, being very common in the major part of its distribution area.

Reindeer lichen, covering the ground around a dead branch from a Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris), Byrums Sandfelt, Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A common bird’s-foot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus) has sprouted among reindeer lichen, Vendsyssel, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Footprints and other signs of deer

The presence of deer is often revealed by their footprints, or by heaps of faeces, called pellets. Many deer species use the same routes every day when foraging, and, over time, animal paths, called tracks, evolve. Some species of deer have a habit of scraping aside withered leaves and vegetation, before they lie down on the forest floor. Larger species often wallow in mud to rid themselves of stinging insects. Sometimes, a population of deer is so large that they prune bushes to get enough food.

Footprints of red deer. In recent years, this species has increased significantly in numbers in Jutland, Denmark, where these pictures were taken. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Footprints of roe deer, and a leaf rosette of scentless mayweed (Matricaria perforata), central Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Footprints, urine, and pellets of roe deer, and tracks of a blackbird (Turdus merula), Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dried-out pellets of mule deer in black lava, Kana’a Lava Flow, Coconino National Forest, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tracks of red deer, Borris Hede, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Roe deer tracks, Funen, Denmark. In the lower picture, withered leaves have gathered in the track. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Resting places of roe deer in a carpet of lesser celandine (Ranunculus ficaria) and white anemone (Anemone nemorosa), Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Resting place of a roe deer in tall grass, Funen, Denmark. The vegetation was too tall for the deer to scrape aside, so it simply lay down upon it. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wallows of red deer, Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These midland hawthorns (Crataegus laevigata) on the island of Romsø, Denmark, have been severely pruned by grazing fallow deer. – Hawthorns are described in detail on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This American holly (Ilex opaca) on Fire Island, Long Island, New York, has been pruned by white-tailed deer. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Deer and Man

Deer have been a source of food for humans from Palaeolitic times. They appear in mythologies of numerous cultures, and artwork, depicting deer, is found throughout their distribution area.

For thousands of years, deer antlers in velvet have been an important ingredient in traditional Chinese medicine, utilized for various ailments, including joint and bone problems, and calcium deficiency, and also as a growth tonic for children, as a remedy against old age, and as an aphrodisiac.

Deer penis is reported to have important therapeutic properties. It is sliced into small pieces, roasted, and dried in the sun. In former days, in Taiwan, women were reported to consume deer penis during pregnancy, as it was believed that it would make the mother and child stronger. The Ancient Mayans were also known to roast deer penis, and Greek physician Hippocrates of Kos (c. 460-370 B.C.) recommended it as an aphrodisiac.

A selection of pictures, depicting the relationship between deer and Man, is shown below.

These rock carvings, depicting reindeer, were made during the Stone Age, 6.000-8.000 years ago. – Tømmerneset, northern Norway. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Another rock carving, depicting a reindeer, made during the Bronze Age, Aspeberget, Bohuslän, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Middle Age mural in Holtug Church, Zealand, Denmark, depicts red deer, a goat, and a gigantic rat. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Jataka terracotta frieze, illustrating a hunter, aiming at a deer, Anauk Petleik Paya, Bagan, Myanmar. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Angkor area in western Cambodia contains thousands of statues, sculptures, reliefs, and carvings from the Khmer Hindu Kingdom, depicting various items, including a wealth of animals. Pictures from this area may be seen on several pages on this website, including Religion: Hinduism, and Plants: Ancient and huge trees.

Khmer relief, depicting two Hindu ascetics with tied-up hair, one embracing a deer fawn, Bayon, Angkor Thom. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Khmer relief, also from Bayon, depicts a fawn, suckling its mother. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In Buddhism, the circular shape of the dharma wheel represents the perfection of the dharma, the teachings of the Buddha. The rim represents concentration during meditation, whereas the hub represents moral discipline. At the centre is a Daoist yin-yang symbol, where yin represents the dark, or negative forces, and yang the bright, or positive forces, the two being intertwined, symbolizing that they are interconnected.

These deer, kneeling beside the dharma wheel, symbolize the deer garden at Sarnath, where the Buddha gave his first teachings. This sculpture was observed on the Jokhang Temple, Lhasa, Tibet. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Daoist relief, depicting a family of sika deer, Fushing Temple, Xiluo, western Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These gaudy clocks are for sale outside the Manakamana Kali Temple, central Nepal, one shaped as a deer, with antlers and all. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Deer antlers in velvet for sale as traditional Chinese medicine, Kowloon, Hong Kong. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Poster, announcing sale of deer antlers and gall bladders from bears, Lhasa, Tibet. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Traffic signs

Numerous countries have traffic signs, depicting deer jumping across the road.

Schladminger Tauern, Austria. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

It seems that a frustrated hunter (or whatever one should call him) has ‘decorated’ this sign in Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This sign, which warns against crossing moose, is from the island of Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Uploaded August 2020)

(Latest update July 2023)