Hippo – the river horse that lives on both sides

Hippos, resting in a pool, Lake Manyara National Park, Tanzania. The birds in the background are yellow-billed storks (Mycteria ibis) and a single great white pelican (Pelecanus onocrotalus). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The origin of hippos is not clear. Previously, it was assumed that they evolved from a pig-like ancestor about 40 million years ago, but genetic research indicates that they are distantly related to whales.

In former times, there were many species of hippo, which were distributed in the major part of Eurasia and Africa. Until about a million years ago, eight species existed in Africa, and on Madagascar three species became extinct in historical times, probably exterminated by people who colonized the island from Indonesia about 2,000 years ago. Today, only two species remain, both in Africa.

Social animal

The scientific name of the common hippo is Hippopotamus amphibius, from the Greek hippos (‘horse’), potamos (‘river’), amfi (‘both sides’), and bios (‘life’), thus ‘the river horse that lives on both sides’. This name refers to the fact that the hippo lives in water as well as on dry land. They are huge animals, where males may be up to 3.5 m long and weigh up to 3 tons.

Hippos are highly gregarious, living in smaller or larger herds, which spend most of the time submerged in ponds or rivers, or basking in the sun along the shores. When sun-bathing, they excrete a red fluid, which was previously erroneously thought to be blood, but is merely sweat. This sweat creates a varnish-like layer, which protects the animal from getting sunburned. In the daytime, their characteristic call, sounding like a honking laughter, is often heard.

The herd is organized in a rigorous hierarchy, each member having its status within it. There is often much squabbling and fighting among the members, and most animals carry a lot of scars on their hides, inflicted by the huge tusks in their lower jaw.

Hippos, sleeping in a pond, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ears, eyes, and nostrils are placed on elevated ridges, allowing the hippo to orientate itself, as soon as it emerges from the water. – Mara River, Masai Mara National Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This hippo is wallowing in mud, belly up, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sun-bathing hippos, Lake Manyara National Park, Tanzania. In the background yellow-billed storks (Mycteria ibis) and white-bearded wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus ssp. mearnsi). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hippos often fight, and most of them have innumerable scars on the body, inflicted by their sharp canines. An Egyptian goose (Alopochen aegyptiacus) is standing on the shore. – Lake Manyara National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female hippo with her newborn calf, Masai Mara National Park, Kenya. The calf has difficulties scaling the river bank. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grazing at night

Usually at night, but sometimes during the day, hippos go ashore to graze, mostly on grasses. They eat up to 60 kilos every night, their 14 stomach chambers very efficiently breaking down the cellulose of even the toughest grasses. Hippos look very fat, but what you see is pure muscles – in fact there is very little fat on a hippo.

A very peculiar habit of hippos is to spread their dung in the water, flicking their tail back and forth, like a pendulum.

Occasionally, hippos graze during the day. This one was encountered between the staff buildings in Queen Elizabeth National Park, Uganda. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hippos spread their dung in water by flicking their tail back and forth, like a pendulum. In the foreground are various feeding waders, in the background an Egyptian goose (Alopochen aegyptiacus). – Lake Manyara National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

One of the most dangerous animals in Africa

When you watch a hippo sunbathing or wallowing in mud, it looks quite docile, but in reality, it is among the most dangerous animals in Africa. If it feels threatened on its nightly foraging trip, it will run towards the water as quickly as possible, and should any creature be so unhappy as to block its way, it will surely be trampled.

If a hippo feels threatened in the water, for instance by a passing canoe, it attacks without warning, its huge teeth crushing the canoe and everybody in it.

Hippos can crush a canoe with a single bite from their enormous jaws. – Banagi River, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hippos and people

In former days, the common hippo was distributed over most of Africa – even in the Sahara Desert, about 10,000 years ago, when the vegetation here was lush. It was also found along the Nile River, all the way up through Egypt, where it became extinct, probably due to hunting.

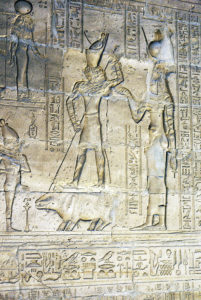

In ancient Egyptian mythology, the god Seth was often depicted as a hippo. He was a grim fellow, who killed his brother Osiris and spread his parts all over Egypt. When reaching adulthood, the falcon-headed god Horus, son of Osiris, revenged his father, killing Seth. The ferocious battle between the two is often depicted in Egyptian temples.

In the major part of Africa, hippo meat is much relished by people, and it has become extinct in countless places due to overhunting. Hippos are also often killed because of the damage they cause by eating crops. Today, the species is only common in some national parks and private game parks.

In Columbia, a herd of hippos, once owned by the late drug baron Pablo Escobar, has spread to wetlands near his former estate. Nobody knows, how many animals are living in the wild here, but they constitute a growing threat to the local wildlife. (Source: bbc.com/news/magazine-27905743)

The battle between Horus and Seth is depicted in many Egyptian temples, here in the Temple of Horus, Idfu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The lantern in the picture below, depicting a weight-lifting hippo, was exhibited during the Lantern Festival, which takes place in Taiwan during Chinese New Year, in this case in the city of Tainan, celebrating the Year of the Rooster (2005). – Other pictures depicting lanterns from this festival may be seen on the page Culture: Folk art of Taiwan.

(Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Huberta’s story

Not all wild hippos are dangerous, and some can even get accustomed to people, becoming quite docile. One such hippo was Huberta, which was initially called Hubert, as she was thought to be a male. In 1928, she left her home in Zululand and began wandering. For more than two-and-a-half years, she amazed biologists by walking about in fields, villages and even towns, sometimes covering several kilometres a day. Altogether, she walked more than 1,600 km.

Local papers began writing about her, and when, by chance, it would often rain when she arrived at a new location, the natives began to regard her as some sort of rain god. Many Zulus viewed her as a reincarnation of Shaka kaSenzangakhona (c. 1787-1828), also known as Shaka Zulu, a famous ruler of the Zulu Kingdom. This belief was reinforced, when two members of the tribe, who had been laughing and throwing stones at her, suddenly died in a landslide.

Indians of Natal also regarded her as a reincarnation and worshipped her in their temples. Farmers fed her cabbages, celery, sugarcane and other goodies, and when they failed to do so, she would gorge herself in their fields, ploughing up vegetables with her sharp tusks.

When she entered Durban, the town had planned a party in honour of her, feeding her a huge bundle of sugarcane. However, a sign on top of the bundle, saying Welcome Hubert, scared her, so she trotted off, entering Victoria Park, where she dined on exotic flowers. These, however, made her thirsty, so she went in search of water. Snatching guavas and other fruits from a fruit vendor on the way, she hastened towards the town reservoir, where she had a bath.

Huberta soon got tired of people, who wanted to scratch her back, and set off for the town of East London, about 400 km down the coast. Despite her having been declared Royal Game – and thus protected – by the Natal Provincial Council, she was shot by hunters, when she had almost reached East London. Following a public outcry, the hunters were arrested and fined £25.

The carcass of Huberta was shipped to London to a taxidermist, arriving back in South Africa in 1932. Today, she is displayed in the Amathole Museum (formerly the Kaffrarian Museum), King William’s Town, Eastern Cape Province. In 1953, citizens of Durban erected a life-size statue of her in Victoria Park.

The carcass of Huberta was shipped to London to a taxidermist, arriving back in South Africa in 1932. (Photo: Public domain)

Pygmy hippos

The pygmy hippo (Choeropsis liberiensis) is a much smaller species, only about 1.6 m long. It is found in ponds and small rivers in rainforests, and, like its larger cousin, is semi-aquatic. Unlike the common hippo, the pygmy hippo lives singly, or a mother with her calf – rarely up to three animals together. It is also much less vocal than the common hippo.

Although the pygmy hippo has been legally protected since 1933, it is very rare today, restricted to four river systems in West Africa. Its rainforest habitat has been cleared to create farmland, and by the logging industry. It is also hunted illegally. Today, the pygmy hippo is threatened with extinction.

A sister species was the little-studied Malagasy pygmy hippo (C. madagascariensis), one of three recently extinct hippo species from Madagascar. The Malagasy pygmy hippo was of similar size to C. liberiensis, but was more terrestrial, inhabiting forested highlands. It is believed to have gone extinct within the last 500 years. In former times, very similar species lived in East Africa, India, and southern Europe.

Grazing male pygmy hippo, Givskud Zoo, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

References

Harris, J.M. 1991. Family Hippopotamidae. Koobi Fora Research Project, Vol. 3. The Fossil Ungulates: Geology, Fossil Artiodactyls and Paleoenvironments. Clarendon Press, Oxford: 31-85

Lake, A. 1955. Killers in Africa. W.H. Allen

Witz, L. 2004. The making of an animal biography: Huberta’s journey into South African natural history, 1928-1932. Kronos 30: 138-166

(Uploaded February 2016)

(Latest update May 2020)