Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Iraq 1973: Dust storm and sheep’s head

By now, we have been in Iraq for a month and are well aware, that when someone presents himself as a tourist guide, he is invariably an agent from the ubiquitous secret police.

The Iraqi government has a dense network of plain-clothes policemen, whose job it is to find and eliminate people, who oppose the Baath Party and its peculiar Islamic type of socialism. The police operate through a huge number of informers, scattered across the entire country.

Before we became aware of this fact, we often tried to discuss politics with Iraqis, but almost everyone avoided the topic, and we now very well understand their reasons. Enemies of the system are thrown in jail without trial.

To avoid the Iraqi people being subject to harmful Western ways of thinking, members of the secret police are surveying all tourists to make sure that they do not impose their imperialistic ideas on people, or fraternize with dangerous elements, i.e. enemies of the regime.

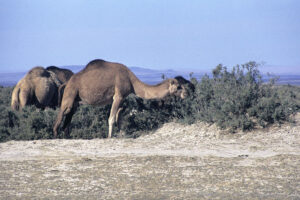

The following morning, after shopping in the souk, we drive into the desert, accompanied by our ‘guide’. Near a couple of black nomads’ tents, a huge herd of camels is grazing – more than 500.

We pass through farmland, where many fields are covered in a layer of salt, washed out from the soil due to excessive irrigation. Farm houses here are often surrounded on all sides by fences, made from thorny shrubs, to keep wolves and other wild animals away from the sheep and goats at night.

Here and there are green groves of date palms and fruit trees, and in the shade beneath them people grow vegetables. White-throated kingfishers (Halcyon smyrnensis) and Indian rollers (Coracias benghalensis) are perched on branches, surveying the surroundings for prey, and collared doves (Streptopelia decaocto) are cooing among the trees.

We arrive at a road block. Oh no, not again! Throughout our journey in Iraq, we have spent a considerable amount of time at these road blocks, because the policemen always scrutinize our papers, and as their English is often very poor, this takes time. But thanks to our ‘guide’, the policemen at this road block are remarkably fast, and we can continue after a couple of minutes.

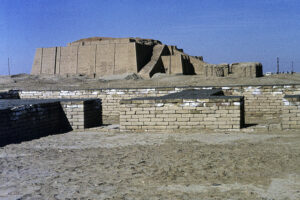

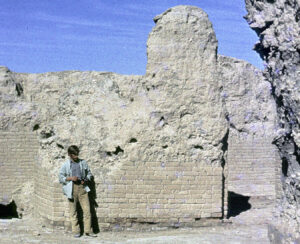

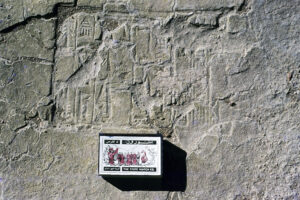

Excavations started here in the 1920s, supervised by British archaeologist Leonard Woolley, who had spent 12 years searching for the place. Royal tombs were found, containing skeletons, weapons, jewelry of gold and lapis lazuli, a unique golden helmet, mosaics, etc.

The remains of a 25-metre-high temple tower, shaped like a step pyramid, were excavated. Such buildings are called ziggurats, and this particular one may have been one of the famous ‘hanging gardens’, where crops were grown on fields on the terraces. Perhaps the top of the ziggurat was an astronomical observatory, as the Sumerians were moon worshippers. The temple of the Moon God Nanar was also excavated by Woolley.

Evidence of the Biblical Deluge was found near these ruins. A layer of sediments, many feet thick, does not contain any cultural remains, whereas the layers below and above these sediments do. The layer without artifacts bears testimony of a tremendous flood, inundating this land around 3000 B.C.

From the top of the ziggurat there is a marvellous view, but for some reason or other it is not allowed to take photographs from here. Among the ruins we find a brick with an imprint of the seal of King Ur-Nammu, who ruled c. 2100 B.C.

We notice tracks that look like large dog tracks, and our guide is of the opinion that they are made by wolves (Canis lupus), which are common in this area.

“Goodbye, Mister,” he says.

“Goodbye, and thank you.”

“What a snot nose!” says Arne, when the man has left. “They are not quite right in their head!”

We commence our journey. Numerous waders are foraging in small puddles along the road, including white-tailed plovers (Vanellus leucurus), marsh sandpipers (Tringa stagnatilis), and Kentish plovers (Charadrius alexandrinus). A passing truck comes to a stop, and the driver hands us two refreshing oranges.

Suq as-Shukh is a cluster of dilapidated stone houses near the shore of Hoor al-Hamar. Huge flocks of sheep are grazing in the desert, and over the reed beds, marsh harriers (Circus aeruginosus) and pallid harriers (C. macrourus) glide effortlessly in search of prey.

A fisherman throws his net into a small pool, holding on to the top end of the net, to which a rope is attached. Numerous iron rings are attached to the bottom of the net, which is pulled underwater by gravity, hereby trapping any fish that might happen to be below it.

A truck now arrives, and the driver disembarks, followed by several other men. One of them speaks a bit of English, and he informs us that we shall have to make a long detour to cross the river. He suggests that I join him to the local police station to inform the constables about our situation, while Arne will stay back at our van.

My guide and I wade across the stream, and as we approach the village, dogs begin to bark furiously. My companion quickly bends down to pick up a clod of soil, and I don’t hesitate to do likewise. The dogs snarl, but keep a respectful distance.

At the police station, we are received by three friendly constables. The youngest one shows me into his spartan room, while my companion and the two other police officers walk back to the river. By now it is completely dark, and above the village lies the Moon, back down, like a sickle. The young man removes his sandals and commences to pray on a sack on the floor, oblivious of my presence.

When he has finished his prayer, he offers me a cup of tea, but before I can finish it, the two officers return with Arne. They are going to show us the detour, so that we can park in front of the police station and spend the night there. They bring two automatic guns to ensure that nobody will bother us on the way.

The two constables occupy the front seat beside Arne, so I take my seat on a wooden box in the cabin. From my position, I can’t see a thing. The bumpy road shakes the car violently, and I’m tossed from one side of the cabin to the other. To make things worse, I am bored out of my wits, cursing the trip. Why did I have to go? I might as well have stayed at the police station.

Finally, our car comes to a stop, and I can get down and stretch my legs. However, we still haven’t reached our destination. The police officers are busy buying fish from a truck driver, after which we continue our journey on the terrible road. In the head lights, Arne spots a jerboa (Jaculus), jumping over the road.

When we reach our goal, the policemen hand us a fish, and we are served several cups of tea. After our meal we talk with the men, but progress is slow, as they do not speak English, and our Arabic is still very basic.

The road now crosses the railroad track between Nasiriya and Basra. However, we are convinced that the officers did not mention any railroad. We ask some passing nomads, and by using sign language they instruct us to go back across the railroad and follow the track eastwards. We do as we are told, but soon have our doubts again.

A fierce wind starts blowing, and the air is soon filled with dust. This reduces visibility drastically, and around noon we realize that we are completely lost. We stop to have some food and wait for the wind to subside. However, it only gains in force, and we decide to spend the night here, as the road track is now impossible to distinguish from the surrounding desert. We decide to return to Suq as-Shukh the following morning, as we don’t have much petrol left.

However, late in the afternoon a truck arrives, and the driver generously offers to guide us back the way we came from. A man and his son take their seat beside Arne, and again I must retreat to the cabin. As it turns out, this journey is even more terrible than the one the previous evening. The truck driver is driving like a madman, but all Arne can do is to stay close. Our car rattles and bounces, and when a wheel hits a stone or a pothole, the shock-absorbers bottom out. Back in the cabin, boxes fall to the floor, and our belongings are scattered all over.

Hours pass, and by now I feel utterly miserable, wondering why we still haven’t reached Suq as-Shukh. Our car gets stuck in a mud hole, and it takes a while to get it out again. The truck driver returns to see, what became of us, urging Arne to drive faster!

We continue our journey, driving 80-90 km/h – and suddenly we are back in Nasiriya! After thanking the truck driver, we manage to find our familiar camping spot in front of the ‘tourist office’.

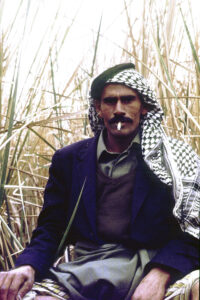

In Diwaya, we shall again try to get into contact with the local tribal people, called Madan, whose way of life is completely adapted to the wetland they live in. There are almost no roads in the marshes, and to get around you must go by boat. The main boat type is a long, slender canoe, called meshof. Motor boats arrived as late as the 1960s, still being a relatively rare sight.

The Madan make a living by growing rice, raising water buffaloes, and by hunting and fishing. Their houses are constructed of reeds, either along the shores of the waterways through the marshes, or on islets.

In the town of Shattra we enquire a man for directions to Diwaya, and at once he guides us to the office of the secret police. Here we are served a cup of tea, while the boss makes a telephone call to his colleagues in Diwaya to inform them of our arrival. He then instructs people to drive in front of us to show the way and to help us pass a road block.

In Diwaya, we are guided to the local police station. Inside this building, on our way to the office, we pass a jail cell, from which several prisoners smile and wave at us. In return, we wave and greet them: “Alab-el-khrer.” (‘Good day.’)

A surly officer receives us, noting down our names, when we have repeated them three or four times. He wants to know where we are going, and when he learns that we would like to eat, he escorts us to a nearby restaurant.

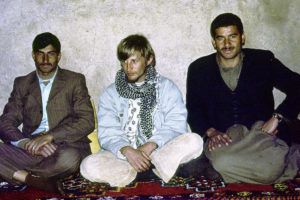

While we are having lunch, we get acquainted with a nice man named Hassan, who speaks a bit of English. We inform him that we would like to go into the marshes, and he volunteers to go with us to a nearby river, Shatt al-Saadir, where three or four villages are situated near the edge of the marshes. Unfortunately, the ‘bloodhound’ is going to join us.

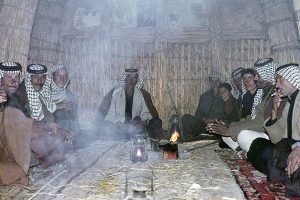

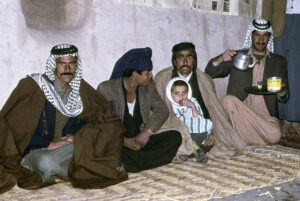

Entering the mudhif, we greet the men gathered here. The centre of the floor is occupied by a huge fireplace, dominated by an enormous coffee pot. We are served coffee in tiny cups, following an ancient ritual. We drink three cups, after which we shake the cup, indicating that we have had our fill. Afterwards, we are served tea.

Several men arrive, and we are now about 25 people gathered in the mudhif. Apart from the fire, it is illuminated by four kerosene lamps. Now, in the far end of the fireplace, another fire is lit, its light flickering on the reed arches. This, and the dense smoke under the roof, creates a cozy atmosphere, only disturbed by a blaring transistor radio.

We are invited for dinner, rice and mutton. Boys bring in the food on small trays, one for each person. As guests of honour, Arne and I are served the best part of the sheep, namely the head, one half for each of us. We glance enviously at the other men, who have been served more genuine mutton. But out of politeness we have to pretend that we are delighted with our share. The brain doesn’t taste too bad, and some scraps of meat can be found here and there on the cheeks. I lift the ear, looking enquiringly at our host, who nods eagerly. Consequently, I crunch the cartilage, smacking my lips politely. The eye is lying in its hollow, looking at me, somewhat accusingly, I imagine. Politeness or no politeness, I just cannot make myself eat it, though my act will break the laws of hospitality. Arne is in similar distress. After the meal we are handed soap and water to wash our hands outside the mudhif.

I have to go to the bathroom, and when I return, Arne informs me that the mudir has tried to persuade him to have sex with him. It seems that the mudir is convinced that since we are travelling together, we must be homosexuals. When Arne has to go to the bathroom, he makes a similar suggestion to me, but I politely decline. The mudir curtly bids us good night and retires to his bedroom.

The following morning, in a restaurant, we enjoy kebab – small chunks of meat, roasted on skewers. A cool wind is blowing, and from the opposite river bank a blaring loudspeaker plays Arabian music. Hassan and his brother join us. The brother is very eager to practice his English on us, finally asking: “Is my English good or bad?”

We are too polite to inform him that it is almost incomprehensible.

When we express our wish to go into the marshes to watch birds, our host takes it for granted that we want to go hunting. What else are birds for? Several men join us, the leader of the village bringing a rifle and a shotgun.

Several canoes lie in the water some distance from the shore, and a boy is sent out to bring two of them ashore, so that we don’t have to wet our feet. Arne and I take our seats in a leaking meshof, punted by two pranksters. All the others are crammed into a larger boat.

We now punt across small lakes and along channels through a dense growth of bulrush (Typha). Our meshof is leaking quite badly, and Arne and I must join the others in the larger boat, which by now is somewhat overcrowded.

A boat approaches us, and after a lengthy talk the men in the boat hand us a coot (Fulica atra), which they have shot. The leader of the village jokes with the men and puts his gun in their face, and when their canoe is about a hundred yards away, he takes his rifle, aiming so that the bullet hits the water a few feet from their canoe!

He is also eager to show us his ability to shoot birds. The other men cheering, he brings down a pied kingfisher (Ceryle rudis), hovering above us, and a black tern (Chlidonias niger), passing the boat. He aims at a flock of pelicans (Pelecanus onocrotalus) far away, but to our intense relief, he misses. Naturally, ducks and coot are very shy and take off at a distance of several hundred yards.

The sky is overcast, and a cold wind is blowing. Back in the village, we enjoy a cup of hot tea. When we leave, the men hand us the three birds.

On our return trip, we are invited for dinner in a village.

Back in Diwaya, the chief of the police force invites us to his home. We hesitate a bit, but, as it turns out, he is much more pleasant than the mudir and not at all inclined to homosexuality.

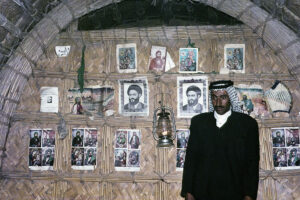

This day is the beginning of the Haj, the annual pilgrimage to the Kaaba, a square building in Mecca which houses a black stone, sacred to all Muslims. This stone – presumably a meteor – was a fetish to the local tribes, long before the foundation of Islam. During the Haj, the most important ceremony is to circumambulate the Kaaba seven times, each time kissing the black stone. A person, who has made the holy pilgrimage to the Kaaba, is honoured by the title of Haji.

Most Muslims cannot afford to make the Haj, so, on this day, people instead try to visit a qubba, a grave of a holy man. We leave in our van, which is fairly crowded, as we bring Hassan, the chief of the police, and two of their friends. We are heading for the tomb of a local holy man, Said Achmet al-Rifai. Said is a title, used by descendants of the Prophet Muhammad.

The road leading to the tomb is an awful dirt track, full of potholes, and sometimes we have to leave the road, crossing an irrigation canal on an incredibly narrow bridge without rails, driving across ploughed fields, and getting stuck in mud.

As it turns out, the qubba is somewhat dilapidated, partly covered in sand, paint peeling off the green dome. A nearby minaret is partly crumbled. Inside the qubba, the coffin of the said is enclosed by a rail, which pilgrims kiss and touch with their forehead. Women tie bits of cloth to the rail to ward off ‘evil eyes’. On the wall, people write their names with chalk, and the chief of the police also writes our names, in Arabic.

On our way back, we stop to cook the birds that were shot the previous day. They are delicious, but then we are hungry.

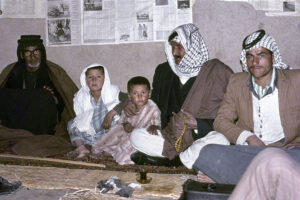

Shortly before Diwaya, we pay a visit to a couple of black nomads’ tents. A camel is lying outside the tents, chewing the cud, others are grazing in the distance. The nomads receive us very courteously, and we are seated on carpets at one end of the tent, surrounded by bleating sheep.

A horse rider, armed with a rifle, arrives at the tent, dismounts and greets us by shaking our hands and kissing our cheeks. He hands us cigarettes, and we talk, frequently interrupted by an elderly woman, who puts her head over a large cloth, which separates the men’s and the women’s sections of the tent.

Suddenly, a fierce gust of wind fills the air with a mixture of dust and rain. We leave abruptly and hurry back to Diwaya. The wind increases in force, and while we sip tea in a tea house, the date palms around the town are bending under the storm.