Plants of Sierra Nevada

Forest of giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum), Sequoia National Park. This species is dealt with below. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Morning light on a forest of quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides), clad in yellow autumn foliage, Conway Summit. This species is dealt with in detail below. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cirrus clouds above the Sierra Nevada, seen from the town of Bishop, Inyo County. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Coniferous forest around Lake Hume. In the background Mount Goddard (4134 m), named after civil engineer George Henry Goddard (1817-1906), who surveyed the Sierra Nevada during the 1850s. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“(…) strange-looking Sabine pine (Pinus Sabiniana), which here forms small groves or is scattered among the blue oaks. The trunk divides at a height at fifteen or twenty feet [4,5-6 m] into two or more stems, outleaning or nearly upright, with many straggling branches and long gray needles, casting but little shade. In general appearance this tree looks more like a palm than a pine. The cones are about six or seven inches [15-17 cm] long, about five [12 cm] in diameter, very heavy, and last long after they fall, so that the ground beneath the trees is covered with them. They make fine resiny, light-giving camp-fires, next to Indian corn the most beautiful fuel I’ve ever seen. The nuts, the Don* tells me, are gathered in large quantities by the Digger Indians for food. They are about as large and hard-shelled as hazelnuts – food and fire fit for the gods from the same fruit.”

John Muir (1838-1914), Scottish-American writer and environmentalist, in his book My First Summer in the Sierra, 1911.

* Mr. Delaney, a sheep farmer, for whom Muir worked during his stay in the Sierra. He was tall and bony, with a sharply hacked profile like Don Quixote.

The Sierra Nevada (‘snowy saw-like mountains’ in Spanish) is a huge mountain range in California and Nevada, varying in width from 75 to 120 km, and stretching over more than 600 km, from the Mojave Desert in the south to the Cascade Range in the north, near the border to Oregon. The vast majority of these mountains is situated in California, although the Carson Range lies primarily in Nevada.

The Sierras harbour three national parks: Yosemite, Sequoia, and Kings Canyon, besides 20 wilderness areas and two national monuments. Prominent features in these mountains include Mount Whitney (4421 m), the highest peak in the lower 48 states, Lake Tahoe, the largest alpine lake in North America, and Yosemite Valley, which is certainly one of the most spectacular valleys on the continent, sculpted by glaciers from ancient granite rocks.

At 496 km2, Lake Tahoe is the largest alpine lake in North America. This picture shows Fanette Island in Emerald Bay. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Yellow lichens on a rock face, Yosemite National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

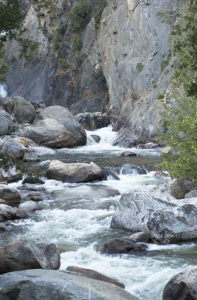

Sierra Nevada is criss-crossed by streams, large and small. This picture shows Roaring River, Kings Canyon National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A number of waterfalls are found in Yosemite National Park, including Vernal Fall (top) and Yosemite Fall, here seen with a rainbow, created by reflections in the vapours from the falling water. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Barren landscape on a hilltop at the southern outskirts of Sequoia National Forest, near Lake Isabella. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kings River, Kings Canyon National Park, with incense cedars (Calocedrus decurrens) growing along the shore. This species is dealt with below. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Two remarkable peaks in Yosemite National Park, El Capitan (left) and Half Dome. They were sculpted from ancient granite rocks by glaciers. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Half Dome is named after its shape. One side is a sheer rock face, whereas the other three sides are smooth and round, making it appear like a dome, cut in half.

An Ahwahneechee legend relates that, long ago, two travellers, Tissiak and her husband Tokoyee, were quarrelling with each other. He became so enraged that he began beating her, which made her so angry that she hurled her basket of acorns at him. As they stood facing each other, they were turned to stone for their wickedness. The acorn basket (Basket Dome) lies upturned beside Tokoyee (North Dome), and the rock face of Tissiak (Half Dome) is stained with her tears.

Half Dome in evening light. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Plant communities

Due to the wide variety of ecosystems and habitats in the Sierras, these mountains are home to numerous plant communities. The superior plant zones are mentioned below, with an indication of typical indicator trees, followed by presentation of a number of species within each of these zones, except the alpine zone, which I have not visited.

1) Foothill grasslands, oak woodlands, and chaparral (including Great Basin dry zone on eastern slopes), altitude c. 300-900 m. Indicator species: grey pine (Pinus sabiniana) and blue oak (Quercus douglasii). Chaparral is a community of shrubby plants, adapted to dry summers and moist winters, which is typical of southern California.

2) Lower montane forest (dry south-western part), altitude c. 900-2100 m. Indicator species: ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) and Jeffrey’s pine (P. jeffreyi).

3) Lower montane forest (moist north-eastern part), altitude c. 900-2100 m. Indicator species: ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) and giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum).

4) Piñon pine – juniper woodland (eastern dry slopes), altitude c. 1500-2100 m. Indicator species: singleleaf piñon (Pinus monophylla) and Utah juniper (Juniperus osteosperma).

5) Upper montane forest, altitude c. 2100-2700 m. Indicator species: red fir (Abies magnifica) and tamarack pine, or Sierra lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta ssp. murrayana).

6) Subalpine zone, altitude c. 2700-2900 m. Indicator species: whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis).

7) Alpine zone, above c. 2900 m. Indicator species: willow shrubs (Salix spp.).

Foothill grasslands, oak woodlands, and chaparral, c. 300-900 m

Aesculus californica California buckeye

An alternative name is this tree is Californian horsechestnut. It is widely distributed in California, but nowhere else, growing along the coast and in lower elevations of the Sierras and the Cascade Range.

Its large fruits, called chestnuts, are poisonous. Several indigenous peoples, including Pomo, Yokut, and Luiseño, used to catch fish by strewing pounded nuts into streams, causing the stupefied fish to float on the surface.

Other members of this genus are presented elsewhere, European horsechestnut (A. hippocastanum) on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees, and Indian horsechestnut (A. indica) on the page In praise of the colour yellow.

Three pictures of California buckeye from Sequoia National Park, showing bare limbs just before foliation (top), bursting leaf buds (centre), and a fallen nut. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pinus sabiniana Grey pine

This pine, also called California foothill pine or digger pine, is one of the indicator species of this zone. It is endemic to California, found from sea level up to an altitude of about 1,200 m. The name grey pine alludes to its grey foliage, whereas digger pine may stem from early settlers, who observed Paiute people digging around these trees for their seeds.

Grey pine, photographed in Pinnacles National Park, western California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Quercus douglasii Blue oak

Another indicator species, sometimes called mountain oak or iron oak. This tree, which is common in the Coast Ranges and in the foothills of the Sierras, is also endemic to California.

The specific name was given in honour of Scottish gardener and botanist David Douglas (1799-1834), who explored the North American flora during three expeditions. He introduced Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and other conifers, especially pine species, as well as a number of bushes and herbs, into British cultivation. In a letter to Sir William Jackson Hooker (1785-1865), director of the Botanical Gardens of Glasgow University, he wrote, “You will begin to think I manufacture pines at my pleasure.”

Douglas died under mysterious circumstances while climbing Mauna Kea in Hawaii in 1834. Apparently, he fell into a pit trap and was possibly crushed by a bull that fell into the same trap. He was last seen at the hut of Englishman Edward ‘Ned’ Gurney, a bullock hunter and escaped convict. Gurney was suspected in Douglas’s death, as Douglas was said to have been carrying more money than Gurney subsequently delivered with the body. (Source: Nisbet, J. 2009. The Collector: David Douglas and the Natural History of the Northwest. Sasquatch Books)

Grassland with open forest of blue oak, Cache Creek Wilderness Area, central California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Quercus garryana Garry oak

This tree, also called Oregon white oak, has a wide distribution, found from southern British Columbia southwards to southern California, growing from sea level to an altitude of about 1,800 m. In the Sierras, a local variety, semota, is a shrub, growing to 5 m tall.

It was named in honour of Nicholas Garry (1782-1856), who was deputy governor of the Hudson Bay Company 1822-35.

Evening light on garry oak, Sequoia National Forest, near Lake Isabella. Acorns of this species are small and rounded. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Quercus wislizeni Interior live oak

An evergreen oak, widespread in California, and also occurring at scattered locations in northern Baja California. It is very common in the lower Sierras.

The specific name was given in honour of Friedrich Adolph Wislizenus (1810-1889), a German-born physician, explorer, and botanist, who first collected it.

Acorns of interior live oak are narrow and pointed. – Sequoia National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Herbs

Amsinckia Fiddleneck

This genus, comprising about 13 species of the borage family (Boraginaceae), is named after the inflorescence, which is curled like the head of a fiddle.

The generic name was given as a tribute to German businessman and politician Wilhelm Amsinck (1752-1831), who was a benefactor of the Hamburg Botanical Garden.

Amsinckia eastwoodiae Eastwood’s fiddleneck

This species is endemic to California, where it grows in various habitats. In the Sierras, it is restricted to the western lower slopes. It has some of the largest flowers of the genus, to 2 cm long and 1.5 cm wide.

It was named in honour of Canadian botanist Alice Eastwood (1859-1953), who created the botanical collection at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco.

Eastwood’s fiddleneck, Sequoia National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hesperoyucca whipplei Chaparral yucca

This impressive plant, formerly included in the genus Yucca, is native to southern California and Baja California, mainly growing in dry, rocky soils in sage scrub and chaparral, up to an altitude of 2,500 m. Its narrow leaves are all basal, to 1 m long, grey-green, stiff, saw-toothed, ending in a sharp point. It only has one inflorescence, a large panicle with hundreds of bell-shaped, white or purplish flowers, situated at the end of a thick stalk, which grows very fast, reaching a height of up to 3 m.

Other common names of this spectacular plant include Our Lord’s candle, in allusion to the huge inflorescence, and Spanish bayonet, which, of course, refers to the needle-sharp tips of the leaves.

The specific name honours Amiel Whipple (1818-1863), head surveyor during construction of the Pacific Railroad.

Chaparral yucca, Sequoia National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lupinus Lupines

A large genus in the pea family (Fabaceae), comprising more than 200 species, which are mainly distributed in the Americas, but also some species around the Mediterranean and in North Africa.

According to Collins English Dictionary, the generic name, and with that the common name, stems from the Latin lupinus (‘wolfish’), referring to an old belief that these plants would ravenously exhaust the soil.

Lupinus stiversii Harlequin lupine

This pretty plant is endemic to California, where it occurs in several separate mountain ranges.

The specific name was given in honour of army physician Charles Austin Stivers, who first collected it in 1862, near Yosemite. The harlequin part refers to the vivid flower colours of this plant, likened to an Italian Middle Age comic figure, Arlecchino (in English Harlequin), who is characterized by his chequered costume.

Harlequin lupine, Yosemite National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lupinus subvexus Valley lupine

Distributed from Washington southwards to California, this species was first described by American botanist Charles Piper Smith (1877-1955). In the Sierras, it is restricted to low altitudes. Its seeds are reputedly poisonous.

Some authorities consider it synonymous with the widespread chick lupine (L. microcarpus).

Large growth of valley lupine, near Jackson, west of the Sierras. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Triteleia ixioides Prettyface

Naturally, this plant, which is also known as golden star, got its common names in allusion to its pretty, yellow flowers, which are arranged in a spectacular umbel-like cluster, situated at the end of a stem, which may grow to 80 cm long. It is distributed between south-western Oregon and central California, growing in various habitats.

Previously, this species was included in the family Themidaceae, but has since been moved to Brodiaeoideae, a subfamily of the asparagus family (Asparagaceae). At least 5 subspecies are known, of which foothill prettyface, ssp. scabra, is mainly restricted to the foothills of the Cascades and the Sierras, growing in open sandy places up to an elevation of c. 2200 m.

Foothill prettyface, ssp. scabra, Sequoia National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Great Basin dry zone on eastern slopes, c. 300-900 m

Cercocarpus betuloides Birch-leaf mountain mahogany

A small tree of the rose family (Rosaceae), growing to 9 m tall. It is native to Oregon, California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Baja California. In the Sierras, it is mainly restricted to chaparral.

This plant has distinctive leaves, which are entire in the lower half, then toothed to the rounded tip. These leaves somewhat resemble birch leaves (Betula), which has given rise to its specific and popular names. The flowers are small and white, and the fruit is a one-seeded nut (an achene), with the long, plumelike style still attached.

The generic name refers to this plume, from the Greek kerkos (‘tail’) and karpos (‘fruit’), thus ‘tailed fruit’. The name mahogany alludes to the hard, dark wood of these trees, but they are entirely unrelated to true mahogany, of the family Meliaceae.

Fruiting birch-leaf mountain mahogany, near Junction View, Sequoia National Forest. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Yucca brevifolia Joshua tree

This large species of yucca is characterized by its many branches. It is a typical plant of the Mojave Desert, in the Sierras growing on the lower, dry, south-eastern slopes. Its popular name stems from Californian Mormons, who encountered this plant on their way to settle with their fellow soul mates in Utah. To them, the outstretched ‘arms’ of this tree recalled the Biblical Joshua, guiding the Children of Israel to the Land of Canaan.

Typical landscapes on the dry eastern slopes of Sequoia National Forest, with Joshua trees and yellow rabbitbrush (see below). (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Shrubs

Chrysothamnus Rabbitbrush

This genus, also known as chamisa, contains 9 shrubs of the composite family (Asteraceae). These plants are found in the western parts of Canada and the United States, eastwards to South Dakota and Nebraska.

The generic name is derived from the Greek chrysos (‘golden’) and thamnos (‘bush’), referring to the golden-yellow flowers of these plants.

Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus Yellow rabbitbrush

This species, also called sticky rabbitbrush, is the most widespread of the genus, occurring from British Columbia and Montana in the north to to California and New Mexico in the south. It is a typical colonizer of disturbed habitats, such as burned land, landslides, and areas prone to flooding.

The specific name is from the Latin viscum (birdlime, made from mistletoe), and floro (‘flower’), thus ‘sticky-flowered’.

Previously, yellow rabbitbrush was utilized medicinally by a variety of indigenous peoples, among the Paiute to treat colds and cough, and among the Hopi for skin problems. Gosiute and Paiute produced chewing gum from latex of the roots, whereas Hopi and Navajo made orange and yellow dyes from the flowers.

Yellow rabbitbrush, observed near Junction View, Sequoia National Forest. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Herbs

Datura innoxia Downy thorn-apple

This shrubby herb of the nightshade family (Solanaceae), also called recurved thorn-apple, prickly-burr, Indian-apple, or moonflower, grows to 1.5 m tall. The most common name stems from the short, greyish hairs, which cover stem and leaves. When bruised, the entire plant has an unpleasant smell of rancid peanut butter. The spectacular white flowers are very large, trumpet-shaped, to almost 20 cm long, in fruit turning into an egg-shaped, spiny capsule, about 5 cm long. The spines often get caught in the fur of animals, which then spread the seeds.

When Scottish botanist Philip Miller (1691-1771) first described this species in 1768, he misspelled the Latin word innoxia (‘inoffensive’), when naming it Datura inoxia. Another name, D. meteloides, has also erroneously been applied to it.

The generic name is the Hindi term for thorn-apples, usually spelt dhatura.

This species is native to south-western United States, southwards to large parts of South America, and it has been widely introduced elsewhere as an ornamental, or inadvertently. It contains the highly toxic alkaloids atropine, scopolamine, and hyoscyamine. The Aztecs used this plant long before the Spanish conquest for many therapeutic purposes, including as a poultice for wounds. The Aztecs warned against ingestion of it, as it might cause madness. Nevertheless, various indigenous tribes used it as a hallucinogenic.

The effects of scopolamine and hyoscyamine are described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry (Hyoscyamus niger). On the same page, you may read an amusing anecdote from 1676, describing the altered mental state of British soldiers, who consumed common thorn-apple (Datura stramonium).

Downy thorn-apple, Kern Valley, eastern California. The yellow shrub in the background is yellow rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus) (see above). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spiral-shaped flower-bud of downy thorn-apple, Sequoia National Forest. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Diplacus bigelovii Bigelow’s monkey-flower

Formerly known as Mimulus bigelovii, this plant grows in deserts and other dry areas in the south-western United States. It is very variable in size and shape, growing from 2 to 25 cm tall. The flower colour is generally magenta, with a yellow throat.

It is one among many species, which were named in honour of surgeon and botanist John Milton Bigelow (1804-1878), who collected many new plant species on expeditions to south-western U.S. and northern Mexico.

Bigelow’s monkey-flower, photographed in Joshua Tree National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Eriogonum Wild buckwheat

A huge genus in the buckwheat family (Polygonaceae), comprising maybe 250 species, all occurring in North America and Mexico.

Eriogonum fasciculatum California buckwheat

This plant, also called flat-topped buckwheat, is distributed from central California southwards to Baja California, growing in a variety of habitats, including chaparral, grasslands, sagebrush scrub, and piñon-juniper woodland.

In former days, it was widely used medicinally by various tribes for numerous ailments, including colds, headache, diarrhoea, and wounds. It was also eaten raw or used in porridges and baked items, and tea was made from leaves, stems, and root. Today, it is a very important source of honey.

Fruiting California buckwheat in evening light, Lake Isabella, Sequoia National Forest. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lower montane forest (dry south-western part), c. 900-2100 m

Calocedrus decurrens Incense-cedar

Formerly called Libocedrus decurrens, this large conifer, growing to about 57 m tall, may have a trunk diameter up to 3 m. Before settlers started logging at a large scale, trees reportedly reached 69 m, with a diameter of 4 m.

It grows very slowly, but can reach an age of more than 500 years. Indigenous tribes utilized it for numerous purposes, the bark to construct temporary conical-shaped huts and also more permanent houses, and to produce fire by friction. Hunting bows and baskets were made from thin branches. It was also used medicinally for stomach problems.

Bark of incense-cedar is thick, on older trees up to 15 cm, with deep furrows, exfoliating in long strips. Yellow lichens are growing on the trunk of this old tree in Yosemite National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fruits of incense-cedar, with Liberty Cap in the background, Yosemite National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dried out trunk of incense-cedar with holes from insect larvae, and fallen needles of ponderosa pine (see above), Kings Canyon National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pinus lambertiana Sugar pine

A typical tree of this zone, the tallest and most massive of all pines, often growing to 60 m tall, the record being 83 m, and with a trunk diameter to 2.5 m, in some specimens even 3.5 m. It also has the longest cones of any conifer, often growing to 50 cm long, rarely to 65 cm.

This species is native from Oregon south through California to Baja California. Scottish botanist David Douglas (1799-1834) named it lambertiana in honour of English botanist Aylmer Bourke Lambert (1761-1842). The common name stems from its sweet resin, which indigenous tribes used as a sweetener. The famous Scottish-American writer and environmentalist John Muir (1838-1914) preferred it to maple sugar.

The sad fate of David Douglas is related above at Quercus douglasii.

Sugar pine is the tallest of all pines, often growing to 60 m high. This towering specimen was photographed in Mariposa Grove, Yosemite National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Branches of a sugar pine, outlined against pale foliage, Mariposa Grove. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Douglas’ squirrel (Tamiasciurus douglasii) in Yosemite National Park is feeding on a sugar pine cone larger than itself. This species, and many other squirrels, are described on the page Animals – Mammals: Squirrels. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pinus ponderosa Ponderosa pine

Also known as bull pine or western yellow-pine, this is an indicator tree of this zone. It grows to a huge size, the record being 81 m. The yellow or orange-red bark of older specimens is very characteristic, cracking into broad plates, bordered by black crevices.

Ponderosa pine is native to a huge area in western United States and Canada, found from British Columbia southwards to southern California, eastwards to South Dakota and New Mexico. It was first collected in 1826 by David Douglas (see previous species), who labelled it Pinus ponderosa, from the Latin ponderosa (‘heavy’), referring to its heavy wood.

Ponderosa pine grows very tall, the record being 81 m. These were observed in Sequoia National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ponderosa pine in morning light, near Junction View, Sequoia National Forest. The yellow-flowered plants in front of the withered grass are prickly lettuce (Lactuca serriola), an introduced plant from Europe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Quercus kelloggii California black oak

This is mainly a tree of northern California and western Oregon, where it grows in foothills and lower mountains. Its occurrence in southern California and Baja California is patchy, but it is common in the Sierras. Most trees live between 100 and 200 years, but some specimens are known to be almost 500 years old.

This species is adapted to fire, protected from smaller fires by its thick bark. It is killed by larger fires, but easily sprouts again from the roots. Acorns mainly sprout, when a fire has cleared an area of leaf litter. This was known by several indigenous peoples, who purposely lit fires to renew growths of this tree, whose acorns was a staple food source to them.

Autumn foliage of California black oak, Kings Canyon National Park. Leaves of this species are deeply cleft, 10-20 cm long. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Feeding tunnels of a species of leaf miner moth create patterns in a leaf of California black oak, Junction View, Sequoia National Forest. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Acorns of California black oak are relatively large, about 3 cm long and 1.5 cm wide. – Junction View, Sequoia National Forest. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Herbs

Anaphalis margaritacea Common pearly everlasting

Also known as western pearly everlasting, this erect herb of the aster family (Asteraceae) grows to 1.2 m tall. It is widespread in North America, from north-western Mexico to Alaska, and in northern Asia, southwards to China and the Himalaya, and thence westwards to eastern Europe.

The scientific name is derived from the Greek ana (‘on’, ‘up’, ‘above’, ‘exceedingly’), phalos (‘white’), and margarites (‘pearl’), thus ‘exceedingly white pearl’, referring to the white, pearl-like flowerheads.

In this picture from Kings Canyon National Park, common pearly everlasting has invaded a burned forest of oak and pines. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Common pearly everlasting, near Junction View, Sequoia National Forest. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Claytonia Spring beauty

A genus of 27 species, which was formerly included in the purslane family (Portulacaceae), but has since been transferred to a separate family, Montiaceae. These plants are distributed mainly in montane areas of northern and central Asia, and in North and Central America. The genus was named to commemorate botanist John Clayton (c. 1694-1773) of Virginia.

Claytonia perfoliata Miner’s lettuce

Formerly known under the names winter purslane and Montia perfoliata, this plant is usually prostrate, but may sometimes grow to 40 cm tall. One of its main characters is the rounded, fleshy leaves, which often encircle the stem.

This species is common in the Sierras. It occurs from southern Alaska southwards through western United States and Mexico to Central America. In Europe, where it has been cultivated as a vegetable as far back as in the 1500s, it is widely naturalized today. The name miner’s lettuce stems from the 1849 Gold Rush in California, when miners ate this plant as a fresh salad, presumably to avoid getting scurvy.

Miner’s lettuce, Yosemite National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Close-up of miner’s lettuce, Sequoia National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Epilobium canum California fuchsia

This shrubby herb of the evening-primrose family (Onagraceae), which grows to 60 cm tall, is native from Oregon, Idaho, and Wyoming southwards to northern Mexico, growing on dry slopes and in chaparral.

Previously, it was called Zauschneria californica, named in honour of physician and botanist Johann Zauschner (1737-1799) of Prague. However, genetic research has revealed that it is in fact a species of willow-herb (Epilobium). The popular name refers to the scarlet flowers, which resemble those of fuchsias. Hummingbirds are much attracted to these flowers, giving rise to two other common names, hummingbird flower and hummingbird trumpet.

California fuchsia, Yosemite National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Erysimum Wallflower

A genus of about 180 species, belonging to the mustard family (Brassicaceae). These plants are native to Europe, the major part of Asia, and North America, southwards to Costa Rica.

Erysimum capitatum Western wallflower

This plant, also called sanddune wallflower or Douglas’s wallflower, has attractive flowers, whose colour varies from bright golden to yellow, red, white, or purple. It is found in western North America, from Alaska southwards to north-western Mexico. Formerly, it was used medicinally by tribal peoples for various ailments, including stomach ache and muscle pain.

Western wallflower, Sequoia National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lower montane forest (moist north-eastern part), c. 900-2100 m

Trees

Abies concolor White fir

Native to montane areas of western North America, this tree is found at elevations between 900 and 3,400 m. Two subspecies have been described, of which the nominate concolor is found from Wyoming westwards to eastern Nevada, southwards to Arizona and New Mexico, just extending into Mexico, whereas subspecies lowiana occurs from southern Oregon through California to northern Baja California.

This species may live up to 300 years. The largest specimens have been found in the central Sierras, the largest one 75 m tall, with a trunk diameter at breast height 4.6 m.

Other pictures, depicting white fir, are shown below (see wolf lichen).

Mixed forest, partly burned, of white fir and ponderosa pine (see above), Mariposa Grove, Yosemite National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Acer macrophyllum Bigleaf maple

As its name implies, this tree, also called Oregon maple, has large leaves – in fact the largest leaves of any maple, often to 30 cm across, with five deeply indented lobes. Usually, it grows 15-20 m tall, but specimens up to 48 m have been encountered. It is native to the Pacific Coast, from southernmost Alaska to southern California. Inland, it occurs in the Sierras, and in central Idaho.

Pictures, depicting the yellow autumn foliage of this species, may be seen on the page Autumn.

Fruiting bigleaf maple, Yosemite National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Alnus rhombifolia White alder

A deciduous tree, to 25 m tall, which grows in moist habitats at altitudes up to 2,400 m. It is distributed from southern Washington and Idaho through Oregon to southern California.

Trunk of white alder, covered in grey and orange lichens, Kings Canyon National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cornus nuttallii Pacific dogwood

This tree, growing to about 25 m tall, has very characteristic inflorescences, with tiny greenish-white flowers clustered in a dense head, which is surrounded by large white bracts. The fruit is a large pink ‘berry’, to 3 cm across, containing 50-100 seeds. It is edible, though not very tasty.

It is native along the Pacific Ocean, from southern British Columbia to southern California. Inland populations are found in the Sierras, and also in central Idaho. In 1956, this tree was appointed as the provincial flower of British Columbia.

In his book My First Summer in the Sierra, from 1911, Scottish-American writer and environmentalist John Muir (1838-1914) writes about this tree: “Nuttall’s flowering dogwood makes a fine show when in bloom. The whole tree is then snowy white. The involucres are six to eight inches [15-20 cm] wide. Along the streams it is a good-sized tree thirty feet [9 m] high, with abroad head when not crowded by companions. Its showy involucres attract a crowd of moths, butterflies, and other winged people about it for their own, and, I suppose, the tree’s advantage.”

The specific name was given in honour of Thomas Nuttall (1786-1859), a British printer, who came to the United States in 1808. Shortly after his arrival, he met botanist Benjamin Barton (1766-1815), who induced a strong interest in natural history in him. During the following years, until 1841, Nuttall undertook several expeditions in America, and numerous plants and animals are named after him.

Pacific dogwood is easily identified by its large white bracts. – Yosemite National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Quercus chrysolepis Canyon live oak

This evergreen oak is common from southwestern Oregon through California to northern Baja California, with scattered populations in Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, and Chihuahua, Mexico. It is the most widely distributed oak in California.

The leathery leaves are entire or toothed, glossy green above. Young leaves are covered in yellowish down beneath, often turning grey and almost hairless the second year. The acorns vary quite a lot, but are mostly ovoid, with a shallow, turban-like, scaly cup, densely covered in yellowish hairs, which have given rise to the specific name, from the Greek krysos (‘gold’) and lepis (‘scale’). After leaching of the tannins, the acorns were a staple food of many indigenous tribes. They have also been used as a coffee substitute.

Acorns of canyon live oak, Yosemite National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sequoiadendron giganteum Giant sequoia

“A grove of giant redwood or sequoias should be kept, just as we keep a great and beautiful cathedral.”

Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), American president 1901-1909.

In the wild, this magnificent tree is found only in the Sierra Nevada. It is the heaviest living being on the planet, the largest ones having an estimated weight of about 2,100 tonnes. This fantastic species is described in detail on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees.

The largest known giant sequoia, called General Sherman, grows in Sequoia National Park. It is about 2,300 years old, 84 m tall, with a diameter of 11 m at ground level, a mass of c. 1,500 m3, and an estimated weight of 2,100 tonnes. Note the burned parts on the lower trunk. Due to their thick, spongy bark, these trees are able to withstand forest fires. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A majestic growth of giant sequoias, Sequoia National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

People appear like midgets, when they stand next to a giant sequoia. – Mariposa Grove, Yosemite National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Turned-up roots of a giant sequoia, covered in yellow lichens and green mosses, Mariposa Grove, Yosemite National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Umbellularia californica California bay laurel

Mainly coastal, this evergreen tree occurs from south-western Oregon southwards through California to the Mexican border. It is quite common in the western foothills of the Sierras.

It grows to 30 m tall, with fragrant lance-shaped leaves, to 10 cm long. The yellow or yellowish-green flowers are arranged in small umbels, which has given rise to the generic name, meaning ‘little umbel’. The fruit is an oval berry, to 2.5 cm long, green at first, purple when mature.

The leaves have been used as a substitute for those of the true bay laurel (Laurus nobilis) in cooking. They were utilized by native tribes for a number of ailments, including headache, toothache, earache, stomach ache, colds, sore throat, and mucus in the lungs. A poultice of the leaves was used for rheumatism and neuralgia.

Flowering California bay laurel, Sequoia National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

California bay laurel with unripe fruits, Kings Canyon National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Shrubs

Arctostaphylos Manzanitas

A group of evergreen shrubs or small trees of the heath family (Ericaceae), occurring from southern British Columbia southwards to Texas and Mexico. They are characterized by smooth orange or reddish bark and stiff, twisting branches. The word manzanita is Spanish, diminutive of manzana (‘apple’), referring to the fruits. Several species occur in the Sierras, often difficult to identify.

Red bearberry (A. uva-ursi), and a presumed hybrid between this species and hairy manzanita (A. columbiana), often called A. x media, are presented on the page Autumn.

Arctostaphylos viscida Whiteleaf manzanita

The ovate, pointed leaves of this shrub, growing to 5 m tall, are not really white, but whitish-green or dull green. It is widely distributed in California and Oregon. It is quite common in the lower montane zone of the Sierras.

The specific name is from the Latin viscidus (‘sticky’), alluding to its glandular leaves and fruits.

In the past, the Miwok people of northern California made cider from the fruits.

Reddish trunk of whiteleaf manzanita, Yosemite National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Whiteleaf manzanita often produces an abundance of white or pinkish flowers. – Sequoia National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fallen flowers of whiteleaf manzanita, forming a carpet on the ground, Sequoia National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sambucus Elder

This genus of about 27 species of smaller trees, shrubs, or large herbs, is found mainly in temperate and subtropical areas of the Northern Hemisphere. On the Southern Hemisphere, they are restricted to parts of Australia and South America.

In the past, this genus and the genus Viburnum constituted the family Sambucaceae, but were then transferred to the honeysuckle family (Caprifoliaceae), and later to the moschatel family (Adoxaceae), which is today called Viburnaceae.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek sambuca, the name of an ancient string instrument of Asian origin. Presumably, elder wood was used in its construction. The name elder is derived from the Anglo-Saxon word aeld (’fire’). In those days, the hollow stems of elder were used to kindle a fire.

Sambucus cerulea Blue elder

This deciduous shrub, which can grow to a height of 9 m, was formerly known as Mexican elder (S. mexicana). In spring, it displays an abundance of butter-yellow flowers, followed by purplish-blue berries in autumn.

It grows in a variety of habitats, including river valleys, woodlands, and exposed slopes with access to water, up to an altitude of 3,000 m. It has a very wide distribution, from British Columbia southwards through much of western United States to north-western Mexico, with scattered occurrence in Oklahoma and Texas.

Many indigenous tribes used the berries of this plant for food, and a number of herbal medicines were produced from its wood, bark, leaves, flowers, and roots. The wood was also used to make pipes and musical instruments, such as flutes and small whistles. A dye was obtained from the berries.

Some authorities reduce this species to a subspecies of the widespread common elder (S. nigra), described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Blue elder, Yosemite National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Herbs

Castilleja Indian paintbrush

This genus, also known as prairie-fire, contains about 200 species, most of which have brilliant red flowers and bracts, whereas a few are orange, yellow, or violet. The vast majority are native to the western parts of the Americas, from Alaska southwards to the Andes. One species, however, C. pallida, is distributed across Siberia, southwards to the Altai Mountains and westwards to the Kola Peninsula.

These plants of the broomrape family (Orobanchaceae) are parasitic, obtaining a large part of their nutrients from roots of other plants. The flowers of some species are edible, and were formerly consumed by various native tribes, but as these plants tend to absorb and concentrate selenium in their tissue, roots and green parts can be very toxic.

An unidentified Castilleja species from Yosemite National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Diplacus aurantiacus Sticky monkey-flower

This shrubby plant, also called orange monkey-flower, and formerly known as Mimulus aurantiacus, grows to 1.2 m tall, with sticky, narrow leaves, to 7 cm long. The flower colour may be yellow, orange, or red.

An attractive plant, distributed from south-western Oregon through much of California, just extending into Baja California. Formerly, members of the Miwok and Pomo tribes used it medicinally for treatment of wounds, burns, diarrhoea, and eye trouble.

Yellow-flowered form of sticky monkey-flower, Sequoia National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Equisetum hyemale Rough horsetail

This plant, also called scouring rush, has an enormous distribution, found in North America, Europe, and northern Asia, southwards to Tibet, Korea, and Japan. It has also been introduced to other countries, including South Africa and Australia, where it is regarded as an invasive.

It grows in wet areas in forests, often on slopes along streams. In Japan, it is cultivated in ponds in ornamental gardens. Certain indigenous American tribes used a decoction of the stems for venereal diseases and as a diuretic.

The name scouring rush stems from its former usage as a scouring remedy, and as sandpaper, due to its high content of silica. The generic name is from the Latin equus (‘horse’), and seta, which has several meanings, including ‘rough’, ‘brush’, or ‘hair’. Seta can refer to the rough, silica-containing stems of these plants, but together with equus, the word means ’horse hair’. With a bit of imagination, a bunch of drying stems do resemble a horsetail.

Other horsetail species are dealt with on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

This picture from Kings Canyon National Park shows the American subspecies of rough horsetail, ssp. affine, which is often yellow above each sheath. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kumlienia hystricula Waterfall false buttercup

This herb was formerly regarded as a species of buttercup, named Ranunculus hystriculus. As its common name implies, it grows in wet places, such as meadows and along streams. It is endemic to the Sierras, where it is restricted to coniferous forests.

Waterfall false buttercup, Yosemite National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Letharia Wolf lichens

Wolf lichens, of the family Parmeliaceae, are widely distributed in North America, Siberia, and Europe. Two species, the common wolf lichen (L. vulpina) and the brown-eyed wolf lichen (L. columbiana), occur in the Sierras.

Native peoples of California utilized these plants for a variety of purposes. Arrow poison was produced from their toxic foliage. Klamath people would soak porcupine quills in an extract of the plants, which dyed them yellow. They were then woven into baskets to make patterns. The Okanagan-Colville tribe used these lichens medicinally, internally for stomach problems, externally for wounds.

In the old days, Norwegians used common wolf lichen to kill wolves and foxes. The toxic foliage was mixed with crushed glass, and then stuffed into a carcass on frozen ground. (The specific name vulpina refers to foxes, in Latin Vulpes.)

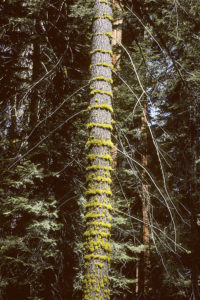

A species of wolf lichen, growing on trunks of white firs (see above), on one of the trees forming concentric rings. – Sequoia National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Close-up of wolf lichen, growing on the trunk of a tamarack pine (see below), Yosemite National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Madia

A genus of 11 species of aromatic and pretty herbs of the aster family (Asteraceae), distributed in western North America and south-western South America.

The generic name is derived from madi, a native Chilean name of the coast madia (M. sativa). Their foliage exudes a fragrant oil, hence the common name tarweed.

Madia elegans Common madia

This plant, distributed from Washington southwards to central California and Nevada, is divided into a number of subspecies, whose flower colour varies from solid lemon-yellow to lemon-yellow with white or maroon centre. The ray florets curl up during the daytime, opening late in the afternoon and staying open all night until mid-morning. The small nut-like fruits (achenes) were eaten raw by several indigenous tribes, or ground into flour and baked.

Common madia, ssp. vernalis, Sequoia National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Primula Shooting stars

These plants belong to a group of primroses, which were formerly placed in the genus Dodecatheon, erected by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), supposedly because the inflorescence of these plants often consists of 12 flowers. The name stems from Ancient Greek dodeka (’twelve’) and theos (’god’), thus ‘twelve gods’. The Ancients applied this name to plants that they thought had acquired their medicinal properties from the twelve most prominent gods and goddesses.

This group, comprising 17 species, is widespread in North America, from north-western Mexico northwards through western United States and Canada to Alaska, with a single species extending into north-eastern Siberia. The flowers are pollinated by bees, which cling to the petals by beating their wings very fast, thus releasing the pollen.

The popular name shooting star refers to the flowers, in which the yellow stamens and the petals, which are bent backwards, converge to a common point, likened to a shooting star, in which the petals constitute the ‘tail’.

Primula jeffreyi Jeffrey’s shooting star

This species, previously named Dodecatheon jeffreyi, is distributed from Alaska and Montana southwards to California, growing in mountain meadows and along streams. An alternative name of it is Sierra shooting star.

The Nlaka’pamux people used the flowers as amulets and love charms.

It was named in honour of Scottish botanist John Jeffrey (1826-1854), who spent four years exploring and collecting plants in Washington, Oregon, and California, sending his specimens back to Scotland. In 1854, he disappeared while travelling from San Diego across the Colorado Desert, and was never seen again.

Jeffrey’s shooting star, Yosemite National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Piñon pine – juniper woodland (eastern dry slopes), c. 1500-2100 m

Juniperus osteosperma Utah juniper

This is a small tree, usually much stunted and only 3-6 m tall, which grows in very dry desert areas and on mountain slopes at moderate altitudes, from southern Montana and Idaho southwards to western New Mexico, westwards to the extreme eastern California. In the Sierras, it is restricted to the eastern slopes and the White Mountains.

Dead Utah juniper, Monument Valley, Arizona. The rock in the background is one of two formations, called The Mittens. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

An unusually straight Utah juniper, Canyonlands National Park, Utah. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pinus monophylla Singleleaf piñon

As its specific and common names imply, needles of this pine are not arranged in groups. It is the only pine in the world with solitary needles.

It is one among several pines of the piñon pine group, which are native to western United States and north-western Mexico, from southernmost Idaho, Utah, and south-western New Mexico westwards to eastern and southern California and Baja California.

This tree, which grows to 20 m tall, usually occurs at altitudes between 1,200 and 2,300 m. It is very common, forming open woodlands, often mixed with junipers. Its edible nuts were an important source of food for indigenous peoples, and they are still widely harvested.

Pale morning light on woodland with forest of singleleaf piñon, Inyo National Forest, White Mountains. The Sierras are seen in the background. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cones and foliage of singleleaf piñon, Joshua Tree National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Upper montane forest, c. 2100-2700 m

Pinus contorta Lodgepole pine

One of the indicator species of this zone is the tamarack pine, or Sierra lodgepole pine, which is a subspecies, murrayana, of the widespread lodgepole pine. This species, divided into four subspecies, is very common in western North America, from sea level to subalpine montane forests.

Tamarack pine is widely distributed in mountains, from Washington southwards to northern Baja California, and thence eastwards to southern Nevada. The nominate contorta is found along the Pacific Coast from southern Alaska to north-western California. Another coastal subspecies is bolanderi, which is endemic to Mendocino County, north-western California. It is threatened by urban development. Finally, ssp. latifolia is found in the Rocky Mountains, from Yukon and Saskatchewan southwards to Colorado.

The specific name is derived from the Latin con (‘with’) and torqueo (‘twisted’), referring to the low, twisted trees, commonly found along the Pacific Coast. This is also reflected in one of the common names of this species, twisted pine.

One of the common names of the lodgepole pine is twisted pine, a suitable name for this specimen of tamarack pine in Yosemite National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cones and needles of tamarack pine, Yosemite National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Populus tremuloides Quaking aspen

Another common tree in this zone is the quaking aspen. This species, which is called by many other names, including golden aspen and trembling poplar, is the most widely distributed tree in North America, found from Alaska southwards through western Canada and the United States to central Mexico, and in a broad belt across Canada and northern U.S. to Newfoundland and New England.

In autumn, the foliage of this iconic species adds vivid splashes of yellow to numerous montane areas in western North America.

Quaking aspens, displaying their brilliant autumn foliage on a mountain slope near Conway Summit. The lower two pictures show the snow-white trunk of this iconic species. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Shrubs

Chrysolepis sempervirens Bush chinquapin

The leaves of this small evergreen shrub, to 2 m tall, have a dense layer of golden scales beneath, giving rise to the generic name, from the Greek krysos (‘gold’) and lepis (‘scale’). The fruit is very spiny, a so-called cupule, containing three edible nuts, which were a common food of indigenous peoples, raw or roasted.

It grows at high elevations, between 1,000 and 3,000 m, distributed from southern Oregon to southern California, and thence eastwards to the Sierras.

The name chinquapin also refers to the related genera Castanopsis and Castanea. This word is a corruption of an Algonquian word, chechinquamin or chincomen, possibly from xinkw (‘great’) and mini (‘fruit’).

Fruiting bush chinquapin, Yosemite National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Herbs

Helenium Sneezeweeds

A genus with about 39 species of the aster family (Asteraceae). The common name was given in allusion to the ancient usage of dried leaves to make snuff, which was inhaled to help sneezing, thus ridding the body of evil spirits.

Originally, Helenium was the name of elecampane (Inula helenium), which, it was said, Helen of Troy planted on the island of Pharos.

Helenium bigelovii Bigelow’s sneezeweed

This plant, found in California and Oregon, grows in wet areas, including meadows and along streams, at relatively high altitudes, from 1,000 to 3,000 m. Cultivated forms are widely grown as ornamentals.

The specific name was given in honour of surgeon and botanist John Milton Bigelow (1804-1878), who collected many new plant species on expeditions to south-western U.S. and northern Mexico.

Bigelow’s sneezeweed, Kings Canyon National Park. In the lower picture, a yellow-faced bumblebee (Bombus vosnesenkii) is feeding in the flowers. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sarcodes sanguinea Snow plant

This parasitic member of the heath family (Ericaceae) derives its nutrients from underground fungi. It is distributed from the Cascade Range in Oregon through montane areas of California, including the Sierras, to northern Baja California, Mexico.

American botanist, chemist, and physician John Torrey (1796-1873) found the colour of this plant so striking that he named it Sarcodes sanguinea, from the Greek sarkos (‘flesh’) and the Latin sanguis (‘blood’), thus ‘the blood-coloured fleshy one’. The common name refers to the early flowering of this species, which often appears, when snow is still covering the ground.

Snow plant, photographed in the Siskiyou Mountains, Oregon. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subalpine zone, c. 2700-2900 m

Pinus albicaulis Whitebark pine

This pine is an indicator plant of the subalpine zone in the Sierras. It is native to montane areas, from British Columbia southwards through Washington, Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming, and with patchy occurrence in Oregon, Nevada, and California. In favourable conditions, it may grow to almost 30 m tall, but at exposed locations it often becomes stunted and twisted.

An old, gnarled whitebark pine, standing on the rim in Crater Lake National Park, Oregon. Yellow lichens are growing on its exposed roots. Crater Lake evolved in the caldera of a collapsed ancient volcano, Mount Mazama. In the picture, Wizard Island is seen in the background. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pinus longaeva Great Basin bristlecone pine

One day, towards the end of April 1992, I was hiking up a slope in Inyo National Forest, White Mountains – an eastern spur of the Sierras. In front of me were the most remarkable trees I have ever seen. At a distance, they appeared completely dead, with twisted, naked branches, stretching from a yellowish trunk towards the blue sky. But then – at closer quarters I noticed a narrow strip of bark on the side of the trunk, which pointed away from the direction of the prevailing wind. This strip of bark was leading up to one or two branches, densely covered in green needles, and from the tip of these branches, small cones were hanging down, their scales equipped with bristle-like appendages.

These peculiar trees are restricted to high-altitude areas in eastern California, and in Nevada and Utah. Apart from certain clones, including a creosote (Larrea tridentata) in the Mohave Desert, whose age is estimated at c. 9,400 years, this pine is the oldest living organism on Earth, a few of them being around 5,000 years old.

Other photos, depicting these remarkable trees, are shown on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees.

Ancient Great Basin bristlecone pines, Inyo National Forest, White Mountains. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Uploaded December 2018)

(Latest update April 2024)