Algae

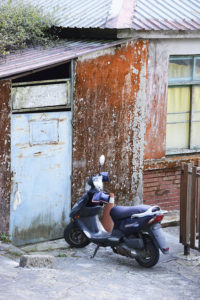

Orange algae, growing on a stone wall, Alishan National Forest, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Seaweed, caught in grass on a beach, Kosa Ruskaya Koshka, Chukotka Peninsula, eastern Siberia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This little girl is playing with green algae, placing them on her head, Langeland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Channelled wrack (Pelvetia canaliculata), a brown alga, growing on a rocky coast, Loch Hourn, Scotland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Green algae, growing on a Hindu sculpture, depicting a tiger, Holy Water Temple, Ubud, Bali, Indonesia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“This kelp, oar-weed, tangle, devil’s-apron, sole-leather, or ribbon-weed – as various species are called – appeared to us a singularly marine and fabulous product, a fit invention for Neptune to adorn his car with, or a freak of Proteus.”

American writer Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862), in his book Cape Cod, first published 1865. – Neptune is the Roman sea god, whereas Proteus is his Greek counterpart.

Algae is a term that covers a large and diverse group of organisms, of which the majority are aquatic and autotrophic (i.e. producing organic material through photosynthesis or through inorganic chemical reactions). Many forms lack most of the distinct cell and tissue types of typical land plants.

Algae range from one-celled microalgae like Chlorella, Prototheca, and Ochrophyta (diatoms) to multicellular forms, including the large seaweeds, of which the largest, the giant kelp (below), may grow up to 50 m long. The most complex freshwater forms are the Charophyta, a division of green algae, which includes Spirogyra and Charales (stoneworts).

Some species of algae form symbiotic relationships with other organisms, in which the alga supplies organic material to the host organism, which, in turn, provides protection to the alga. Examples of hosts are lichens, corals, and sea sponges.

Cyanobacteria (Cyanophyceae)

These organisms, popularly known as blue-green algae, live in freshwater and obtain energy via photosynthesis. Their name stems from their colour, derived from the Greek kyanos (‘blue’). Modern botanists do not regard these organisms as algae, but I include them here due to their popular name.

Proliferate reproduction of these ‘algae’ often takes place late in the summer. They sometimes occur in huge masses, dying ponds and lakes a characteristic bluish-green colour, which is often an indication of pollution with phosphates and other fertilizers to a level that may constitute a health hazard.

This female mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) is swimming about in a ‘soup’ of blue-green algae, Skanderborg Lake, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Blue-green algae in Århus River, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Blue-green and green algae in an alkaline lake, Lake Bogoria, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A profusion of blue-green algae in a pond, Møn, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Green algae (Chlorophyta and Streptophyta)

This huge and diverse group of algae contains between 9,000 and 12,000 species. Both scientific names are derived from Ancient Greek, chloros (‘green’), phyton (‘plant’), and strepto (‘twisted’), the latter alluding to the morphology of the sperm of some members.

At the small coastal town of Laomei, near the northernmost point of Taiwan, is an area of flat coastal rocks of volcanic origin, the major part covered in a species of sea lettuce (Ulva).

(Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Continued erosion by waves at Laomei has created numerous channels in the rocks, some so narrow that when a large wave enters them, the water is pressed upwards like a fountain. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rubble from a Khmer temple, covered in green algae, Ta Prohm, Angkor, Cambodia. – Numerous pictures from this impressive area are shown on the pages Religion: Hinduism, and Decay. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

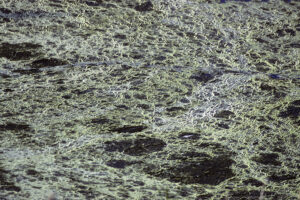

Green algae on the surface of a stagnant river, Wufong, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Green hair alga (Chaetomorpha), washed ashore on rocks, covered in channelled wrack (Pelvetia canaliculata, see below), Loch Hourn, Scotland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Green algae, covering the surface of a forest pond, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Patterns in green algae, growing in a polluted stream, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Green algae on a greenhouse, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Light and shadows on a wall along a canal, overgrown by green algae, Taichung, Taiwan. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Green algae, growing on a Hindu sculpture, depicting a temple guardian, Holy Water Temple, Ubud, Bali, Indonesia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Green algae on a tidal flat during low tide, attached to the shell of a European cockle (Cardium edule), Fanø, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Green algae among rice plants, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pond with green algae, Bumpass Hell, Lassen Volcanic National Park, Cascade Range, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

‘Soup’ of green algae, with bits of foam plastic, Vangså River, Thy, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Green algae, growing on eroded coastal rocks, Montaña de Oro State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Coastal rocks, covered in green algae, Wanli, northern Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Green algae and ivy (Hedera helix), growing on a fence, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These African oystercatchers (Haematopus moquini) blend very well with dark-green algae, growing on coastal rocks, Muizenberg, near Cape Town, South Africa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Green algae, growing on the bark of a dead sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus), Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. This tree is presented on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These stairs in a Hindu temple near Ubud, Bali, Indonesia, are covered in green algae. A Chinese hibiscus (Hibiscus rosa-sinensis) has been left on the stairs as an offering. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Coastal rocks, covered in green algae, Jialeshuei, Kenting National Park, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Edible frog (Pelophylax esculentus) among lush vegetation of green algae and water-crowfoot (Ranunculus), Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Green algae, growing on a surface root of a shoemaker tree (Hieronyma alchorneoides), Reserva Nacional Hacienda Baru, Costa Rica. This large forest tree, to 50 m tall, of the family Phyllanthaceae, is found from Mexico southwards through Central America to Brazil, Bolivia, and Peru, and also in the Caribbean. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Green algae, growing on road signs, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sculpture, depicting a Hindu goddess, covered in green algae and cobwebs, Kintamani, Bali, Indonesia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Green algae on the surface of a pond, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Green algae, growing on hairy bracket (Trametes hirsuta), Funen, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Car wreck with green algae, lichens, and moss, Blekinge, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This shrivelled moon jellyfish (Aurelia aurita) got stuck on a washed-up plank, covered in green algae, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. It somewhat resembles a sad alien. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Despite its orange colour, Trentepohlia aurea is in fact a green alga, distributed almost across the globe. It grows on the trunks and branches of trees, and on rocks and old walls. The orange colour stems from carotenoid pigments in its cells.

Trentepohlia aurea, growing on a rock, Point Reyes National Seashore, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In these pictures, Trentepohlia aurea grows on Monterey cypresses (Cupressus macrocarpa) in Point Lobos State Park, California. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In the Hindu legend The Churning of the Milk Ocean, from the Bhagavata-Purana, it is related that the gods had become weakened and had been usurped by the asuras (demons).

The gods appealed to the supreme god Vishnu for help, and he suggested that they should regain their power by drinking the miraculous amrita, the nectar of immortality, which they could obtain by churning the cosmic milk ocean, thus bringing the jar with amrita to the surface.

However, Vishnu advised the other gods to treat the asuras diplomatically by suggesting them to jointly churn the ocean. When the amrita was brought to the surface, Vishnu would ensure that the gods got hold of it.

The asuras readily agreed to participate in the churning. To perform this stupendous task, the gods and the asuras uprooted the mountain Mandara, placed it upside down in the ocean, and coiled the giant, many-headed naga (serpent) Vasuki around it. By pulling alternately at each end of Vasuki, the mountain would act as a gigantic churn, thus bringing the amrita to the surface.

The mountain, however, began sinking into the ocean floor, causing Vishnu to assume the shape of a giant, named Kurma, half man, half turtle. He then dove to the bottom of the sea, where he placed Mandara on his back, thus preventing the mountain from sinking.

Finally, the jar with amrita surfaced, whereupon a fierce battle between the gods and the asuras ensued, the latter grabbing the jar and running away with it.

Again, the gods appealed to Vishnu, who assumed the form of a new avatar, Mohini, a beautiful goddess, who seduced the asuras and managed to get hold of the jar of amrita, thus preventing evil from becoming eternal, and preserving the good.

Due to the role of Kurma in the legend The Churning of the Milk Ocean, turtles are sacred to Hindus. These sculptures, overgrown by green algae, were encountered in a temple in Ubud, Bali, Indonesia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stoneworts (Charophyceae)

Stoneworts are a class of green algae, comprising about 400 species worldwide, most of which grow in freshwater, a few in brackish water. These organisms may grow to 1.2 m long and are strongly branched, with leaves in whorls. They produce energy via photosynthesis. They are often abundant in clear lakes and ponds, but disappear with growing eutrophication, suffocated by increased production of plant plankton.

The name stonewort stems from a layer of calcium carbonate, which over time may be encrusted on these plants.

Young man with a lush growth of stoneworts, eastern Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red algae (Rhodophyta)

One of the oldest groups of algae, containing over 7,000 species, the vast majority consisting of marine algae, including many notable seaweeds, whereas they are rare in freshwater habitats.

The scientific name is derived from the Greek rhodon (‘rose’) and phyton (‘plant’), thus ‘rose-coloured plant’.

‘Soup’ of filamentous red algae, Cape of Good Hope, South Africa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red algae in sea water along a coast, Ottenby, Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Washed-up red algae, Vangså Beach, Thy, Denmark (upper 2), and Mols, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red algae, living on the surface of snow, Sognefjellet, Norway. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Brown algae (Phaeophyceae)

A huge group of large algae, comprising between 1,500 and 2,000 species, including many species in colder waters of the Northern Hemisphere. In daily speech, brown algae are often called kelp or seaweeds. Some members of the group are consumed by people, especially in the Far East.

Unidentified species of brown algae, Hermanus, South Africa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This large brown alga was washed ashore near Algeciras, Spain. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Washed-up brown algae have attained a reddish colour, Kapelludden, Öland, Sweden. The ruin in the background is Sankta Brita’s Kapell (‘Saint Birgitta’s Chapel’). The story behind this chapel is related on the page Religion: Christianity. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Washed-up brown algae are often used by breeding birds as nesting material.

Incubating common eider females (Somateria mollissima), well camouflaged among washed-up seaweeds, Mågeøerne, Funen, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Where the great cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo ssp. sinensis) breeds on the ground, it often builds tall nests, consisting of washed-up kelp, which, when dry, makes a stable foundation for the nest. – Mågeøerne, Funen (top), and Svanegrund, eastern Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cormorants often bring green plants to their nest. – Svanegrund. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cormorant chicks in a seaweed nest, Mågeøerne. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nest of herring gull (Larus argentatus) among washed-up brown algae, containing two chicks and an egg, Svanegrund, eastern Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera)

This is the largest of all algae, to 50 m long, capable of growing up to 60 cm a day. It forms dense stands along the coast from south-eastern Alaska southwards to Baja California, and is also found along the shores of southern South America, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.

This giant kelp, several stories high, is displayed in the Monterey Aquarium, California. Other pictures from this gorgeous aquarium may be seen on the pages In praise of the colour orange, and In praise of the colour blue. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This specimen was washed up on Melkbosstrand, near Cape Town, South Africa, and is now partly covered by sand. Table Mountain is seen in the background. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bladder wrack (Fucus vesiculosus)

This species is found on the Atlantic shores of Europe, eastwards to northern Russia and the Baltic Sea, in Morocco, the Canary Islands, Madeira, and the Azores, and also from Greenland and eastern Canada southwards to North Carolina.

Attached to stones and rocks, the branched fronds of this plant may grow to 90 cm long and 2.5 cm wide. Along both sides of the prominent midrib are a number of almost globular air bladders.

Since 1811, this species has been a source of iodine, utilized to treat goitre, a swelling of the thyroid gland, caused by lack of iodine.

Bladder wrack, Loch Hourn, Scotland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Knotted wrack (Ascophyllum nodosum)

This species, also known as egg wrack, is the only species in the genus Ascophyllum. The fronds, to 2 m long, are olive-green or olive-brown, without midrib. They are inflated at regular intervals, forming large, egg-shaped air bladders.

It is restricted to the northern Atlantic Ocean, from Svalbard southwards to Portugal, in eastern Greenland and southwards to the north-eastern coasts of North America.

Knotted wrack, Loch Hourn, Scotland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Channelled wrack (Pelvetia canaliculata)

This plant, the only member of the genus Pelvetia, grows in dense, branched tufts, to 15 cm long, and the fronds are deeply channeled on one side, an aid to avoid drying out at low tide. It is common on the Atlantic shores of Europe, from Iceland and Norway southwards to Spain and Portugal.

In Ireland, where this species is known as dúlamán, it was collected for food during famines. A local folk song, Dúlamán, describes a growing relationship between two people who collect the seaweed as a profession.

Rocky coast, covered in channelled wrack, Dervaig, Isle of Mull, Inner Hebrides, Scotland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Channelled wrack, Loch Hourn, Scotland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Postelsia palmaeformis Sea palm

This plant, named for its superficial resemblance to palm trees, is the only member of the genus. It is distributed along the west coast of North America, growing on rocky shores with constant waves. It is one of the few brown algae that can survive and remain erect on land. In fact, it spends most of its life exposed to the air.

The generic name was given in honour of German-Estonian geologist and artist Alexander Philipov Postels (1801-1871).

Sea palm, growing on a rock, Salt Point State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana)

This plant forms thick stands, comprising an important part of the kelp forests along the Pacific Coast of North America, from the Aleutian Islands southwards to southern California. It is attached to rocks and has a cylindric stem to 36 m long, terminating in a dense cluster of blades, to 10 m long and 15 cm wide.

The generic name is derived from the Greek Nereis (originally a sea god, but in Latin meaning a mermaid), and cystis (‘bladder’), thus ‘mermaid’s bladder’. The specific name was applied in honour of German-Russian navigator, geographer, and Arctic explorer Friedrich Benjamin Graf von Lütke (1797-1882), in Russia known as Fyodor Petrovich Litke.

Bull kelp, photographed at various locations in California. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Washed-up bull kelp creates patterns on a stony beach, Salt Point State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Snowy egret (Egretta thula), walking on a ‘carpet’ of bull kelp, Point Lobos State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Yellow or yellow-green algae (Xanthophyceae)

Most of these algae, also known as mustard algae, are yellowish, but may sometimes be bright orange. They mainly live in fresh water, but some are found in the sea, others on land, where they may cling to various surfaces, usually in humid places. They vary from single-celled flagellates to simple colonies and filamentous forms. Supposedly, their nearest relatives are the brown algae.

The Baishuei Terraces in the Yunnan Province, south-western China, are an area consisting of snow-white calcium bicarbonate, which has been deposited by water, seeping down a slope. Over the millennia, terraces have been formed, which are sacred to the local Nakhi-people, described on the page People: Chinese minorities.

This pool on the Baishuei Terraces is brimming with yellow algae. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In the humid and mineral-rich air, which surrounds the Wai-O-Tapu Thermal Area, New Zealand, numerous trees and branches are covered by orange-yellow algae. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The outline of orange and green algae on a wet rock in a park in Taichung, Taiwan, resembles a rather sleepy dinosaur. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Orange alge on the trunk of a spruce, Thy, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The natural range of the Monterey pine (Pinus radiata) is limited to a few locations in Santa Cruz and San Luis Obispo Counties, central California, and two islands, Guadalupe and Cedros, off the west coast of northern Baja California, Mexico. In its natural range, it is seriously threatened by an introduced species of fungus, the pitch canker (Fusarium circinatum).

Elsewhere, however, this tree has been planted extensively, especially in Australia, New Zealand, Spain, Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Kenya, South Africa, and the island of Tristan da Cunha.

The trunk of this Monterey pine in Wai-O-Tapu Thermal Area is partly covered by an orange-yellow alga. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In the humid air in the Mangapohue River Gorge, New Zealand, these yellow algae have managed to fasten themselves on a wire netting. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Horsechestnuts and buckeyes, genus Aesculus, are native to temperate areas of the Northern Hemisphere, with one species in Europe, which originally stems from the Balkans, c. 10 in Asia, and 7 in North America. The European horsechestnut (A. hippocastanum) is presented on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees, whereas an American species, the California buckeye (A. californica), is dealt with on the page Plants: Plants of Sierra Nevada.

Indian, or Himalayan, horsechestnut (Aesculus indica) is common in the western parts of the Himalaya at elevations between 900 and 3,000 m, from Kashmir eastwards to western Nepal.

In parts of northern India, the leaves are used as cattle fodder, and the seeds are dried and ground into a bitter flour, called tattawakher. The bitterness is removed by thoroughly rinsing the flour, which is often mixed with wheat flour to make chapatis, and also halwa (sweet cakes). During hunger periods, a type of porridge, called dalia, is made from it. This species is also utilized in traditional medicine for a number of ailments, including skin problems, rheumatism, and headache. (Source: N.P. Manandhar 2002. Plants and People of Nepal. Timber Press)

The trunk of this Indian horsechestnut in Great Himalayan National Park, Himachal Pradesh, is partly covered by a bright yellow alga. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Khmer relief, depicting a Hindu goddess or a noble lady, is partly covered by orange algae, Bayon, Angkor Thom, Cambodia. – Numerous pictures from this impressive area are shown on the pages Religion: Hinduism, and Decay. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The pond in the picture below, on the island of Fanø, Denmark, is filled with a yellowish alga. The floating leaf is of a white waterlily (Nymphaea alba), whose leaves are usually various shades of green, but for some reason this leaf has turned orange-yellow. The green stems in the foreground are common spike-rush (Eleocharis palustris).

(Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This house wall in Alishan National Forest, Taiwan, has acquired patina from an orange alga, growing on it. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Uploaded September 2021)

(Latest update April 2024)