Poultry

Crowing rooster, Hanoi, Vietnam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Purchases at a market in Yuanyang, Yunnan Province, China: a rooster and vegetables in a basket. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mass breeding of Beijing ducks, near Fuxing, south of Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dyed chickens and ducks for sale, Hanoi, Vietnam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

”Old McDonald had a farm…” – These gigantic paper lanterns, depicting a farmer with buffalo cart, geese, and a goat, are exhibited during the Festival of Lanterns, celebrated during Chinese New Year 2005, Tainan, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chickens

The Red Rooster

I have a little red rooster, too lazy to crow ‘fore day,

I have a little red rooster, too lazy to crow ‘fore day,

Keep everything in the barnyard upset in every way.

Oh, the dogs begin to bark, hound begin to howl,

Oh, the dogs begin to bark, hound begin to howl,

Oh, watch out, strange kin people,

‘Cause the little red rooster’s on the prowl.

If you see my little red rooster, please drive him home,

if you see my little red rooster, please drive him home,

There ain’t no peace in the barnyard

since the little red rooster been gone.

Blues song, credited to American blues musician, singer, and songwriter William James Dixon (1915-1992). The song was first recorded in 1961 by American blues singer and guitarist Chester Arthur Burnett (1910-1976), better known by his stage name Howlin’ Wolf.

In the early 1900s, it was a common belief in the American South that a rooster contributed to peace in the barnyard.

Recent studies indicate that chickens, or simply fowl, were first domesticated in China about 8000 B.C., descended from the red junglefowl (Gallus gallus), which is still found in the wild in India and Southeast Asia. Later, about 6000 B.C., domestication of the red junglefowl also took place several places in Southeast Asia and in India, where some hybridization with the grey junglefowl (Gallus sonneratii), living in the southern part of India, may have occurred.

By 3900 B.C., chickens were present in Iran, by about 2400 B.C. in Turkey and Syria, and by 2000 B.C., they had reached Spain. They arrived about 1400 B.C. in Egypt, where they were called “the bird that gives birth every day” – in allusion to the prolific egg-laying of the species. In West Africa, Iron Age farmers in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Ghana were keeping domesticated chickens from about 500 A.D.

From Southeast Asia, sailors brought chickens to the Polynesian islands about 1300 B.C., and in Chile, remains of domesticated chickens, dating from c. 1350 A.D., have been excavated. Before these excavations, it was believed that the first chickens to arrive in the Americas were brought by Columbus on his second voyage in 1493. Chickens arrived in Australia with the First Fleet, bringing settlers to the continent in 1788.

Today, the chicken is the most numerous and widespread domestic animal, with a total population of more than 19 billion. Chickens are kept primarily as a source of food, both meat and eggs.

Roosters can be very aggressive. Below is an excerpt from the memoirs of my father, Jens Christen Pedersen: “The caretaker of Tåning co-op shop had humour. He kept chickens at the other side of the road, including a handsome rooster. One day he told me to bring the sweepings from the warehouse to the chickens. Usually he did that himself, but I soon found out why he wanted me to do it. When I entered the chicken yard, the rooster at once jumped on me, so that I had to retreat in a hurry and close the door. Meanwhile, the caretaker was bent double with laughter.”

It is often said that chickens are stupid, but I have a true story which shows that chickens are able to reason. In 1980, Thomas Læssøe was working in Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. They had chickens, which were ushered into the hen house every evening, and the door was closed, so that fox or marten couldn’t get in.

One evening, after dark, Thomas was working at the typewriter, when he heard a pecking sound from the window. Looking up, he saw a hen outside, looking in. When he went outside, the hen came running round the house corner to be let into the hen house. It seems that it had been too late to be let in with the other hens.

Thus, the hen must have been reasoning like this: “There is light in this window. Light is connected with those two-legged creatures that let us into the hen house. If I peck on the window, one of these creatures will probably come and let me in.”

Some chicken breeds still resemble their wild progenitor a great deal, including this old Danish breed. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Early in the morning, these chickens in Namche Bazaar, Khumbu, eastern Nepal, are still sitting on their night roost – a pile of firewood. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Crowing rooster in front of a Hindu shrine, Bhaktapur, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This man in the Jhong River Valley, Mustang, central Nepal, is guarding wheat and buckwheat, drying in the sun. He fell asleep on his post, which was soon detected by nearby chickens, who take advantage of it to fill their gizzards. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chick, a few days old, Denmark. The incubation period of chickens is 21 days. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This hen is showing her chickens how to feed. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chickens love dust bathing, which will often rid them of parasites like fleas. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chickens are often kept under cruel conditions, like these cage chickens in Palapye, Botswana. Today, an increasing number of consumers buy eggs and chickens of free-running chickens, whose feed has been grown organically. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These chickens, stuffed into a small cage, are waiting to be brought to a market, Hanoi, Vietnam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chickens for sale at a market near Er Hai Lake, Yunnan Province, China. To prevent them from straying, their feet have been tied together. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Porters, transporting chickens in cages up the Kali Gandaki Valley, Annapurna, central Nepal, to be sold at various restaurants. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This chicken house in the village of Gul Bhanjyang, Helambu, Nepal, is constructed of materials at hand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This enormous paper lantern, depicting a rooster, is exhibited during the Festival of Lanterns, celebrated during Chinese New Year 2005 (the Year of the Rooster in the Chinese Zodiac), Tainan, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This sculpture in the city of Rochefort en Terre, Brittany, depicts a crowing rooster. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

For thousands of years, cock fighting was a popular sport in many countries, including India, Indonesia, China, Japan, and Polynesia. Two trained cocks, often with metal spurs attached to their natural spurs, were released, fighting until one of the contestants was dead, slashed by the spurs. Cock fighting is still practiced in a few countries today.

This Khmer frieze in Angkor Thom, Cambodia, depicts a fight between cocks, owned by Khmer people (left), and by Chinese, identified by their pigtail. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cock fighting is still practiced in a few countries today, here in Sarawak, Borneo. Before the fight, metal spurs are tied to the spurs of the cock. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ducks

Almost all domestic ducks are descended from the mallard (Anas platyrhynchos), which is very widely distributed across subarctic, temperate, and subtropical areas of North America, Eurasia, and North Africa, southwards to Mexico. Morocco, Egypt, Pakistan, and China. It has also been introduced to many other places as a hunting object, including South America, New Zealand, Australia, and South Africa. The drake is a gorgeous bird in breeding plumage, with grey sides, purple breast, and glossy-green head, with a blue shine from certain angles. The female is a uniform speckled brown.

Mallards were first domesticated at least 4,000 years ago, in Southeast Asia. In Ancient Egypt, ducks were captured in nets and then bred in captivity, and domestic ducks are frequently depicted in Egyptian wall paintings in graves and elsewhere. At an early stage, ducks were also farmed by the Romans. The Beijing duck (formerly called Peking duck), a distinct breed in China, also descended from the mallard.

In many places, white domestic ducks developed, probably being favoured in preference to darker breeds, as they were easy to spot, in case they should stray. Domestic ducks have also lost the territorial behavior of the mallard, being less aggressive. Despite these differences, domestic ducks are still very closely related to the mallard, the two forms producing fertile offspring. These semi-tame ducks, which are often found in city parks, come in all plumages, varying from pure white to ‘almost-wild-mallard-type’.

Ducks are mainly farmed for their meat and eggs, and for their down. In some countries, the blood from slaughtered ducks is used as an ingredient in various dishes. Some breeds have been developed for ornamental reasons and are often exhibited in competitions.

The mallard drake is a beautiful bird. – This one was photographed on the islet of Christiansø, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female mallard, resting on a fallen log in a pond, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. The bird in the background is a sleeping common teal (Anas crecca). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mass breeding of Beijing ducks, near Fuxing, south of Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Selling live ducks at a market in Kintamani, Bali, Indonesia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Barbecued ducks, displayed at a market, Yuanyang, Yunnan Province, China. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Muscovy duck (Cairina moschata) is a type of domesticated duck, which is not descended from the mallard. This duck, which is heavier than the common domestic duck, is native to Central and South America, from Mexico south to northern Argentina.

The name Muscovy duck has nothing to do with the Grand Principality of Moscow, founded in 1283 (in English often called the Muscovy), although the spelling of the duck’s name, with a capital M, could easily lead to this misconception. The name is thought either to be a corruption of musk duck, due to its musky smell, or derived from the Spanish word mosquito, named after the Mosquito Coast in Central America, where Spanish conquistadors first encountered this duck.

The earliest known domestication of the Muscovy duck took place in the Mochica culture, southern Peru, and in coastal Ecuador, by about 50 to 80 A.D. In Bolivia, it is known as a domestic animal from about 600 A.D., and in Central America from about 750 A.D. With the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in the 1500s, the Muscovy duck was taken to Europe, and from there it has spread around the world.

The plumage colour of the domestic Muscovy duck is more variable than in its wild cousin, many of the domestic ducks being pure white.

Feral populations of the Muscovy duck have been established in the United States and southern Canada, as well as in New Zealand, Australia, and various places in Europe.

Speckled Muscovy duck, standing on a rock in the Kali Gandaki River, Annapurna, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pure white Muscovy duck in a city park, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Geese

Domestic geese are descended from two species of wild geese, the greylag goose (Anser anser) and the swan goose (Anser cygnoides). The greylag goose is widely distributed across northern Eurasia, whereas the wild swan goose has a restricted distribution, breeding in Mongolia, northern China, and south-eastern Siberia.

The greylag goose was first domesticated in Egypt, maybe as far back as 1500 B.C., and spread from here to Europe and West Asia. Today, about 80 breeds of this domestic goose are known. The swan goose, which is readily identified by the large knob at the base of the bill, was first domesticated in China, maybe as early as 1000 B.C. The domesticated form, which is often called Chinese goose, comes in about 20 breeds.

Today, both forms of domestic geese are found worldwide, and as the greylag goose and the swan goose are rather closely related, hybrids between the two domestic forms often occur.

Domestic geese are kept for meat and eggs, and for their excellent down, used in quilts, down jackets, sleeping bags, and other items.

Wild greylag geese, Lake Hornborga, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Domesticated swan geese with goslings, Sauraha, southern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Goslings of Chinese goose for sale at a market near Er Hai Lake, Yunnan Province, China. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pigeons

Domestic pigeons descended from the rock pigeon (Columba livia). It is believed that in the wild this species was originally found in southern Europe, northern Africa, and from the Middle East eastwards to Afghanistan and India, with isolated populations in Ireland, Scotland, the Faroe Islands, the Azores, Madeira, the Canary Islands, and the Cape Verde Islands.

However, the bird was domesticated at a very early stage and has since been brought to almost every corner of the planet. Over time, more than a thousand breeds have evolved. In numerous cities around the world, birds have escaped to form huge feral populations. Feeding these birds is often a very popular occupation, despite the fact that they are a nuisance, dropping their guano everywhere, and maybe also spreading contagious diseases.

A specialized type of domestic pigeons are so-called homing pigeons, which are a bred for navigation and speed. They originally developed through selective breeding to carry messages to their home place, tied to one of their legs. It is believed that they were able to find their way mainly through sensitiveness to the magnetic field of the Earth. Today, this variety is used in the sport of pigeon racing, which is very popular in many countries.

The specific name stems from Theodore Gaza’s work from 1476, Aristotelis de natura animalium, in which he translates the Greek word for dove, peleia (probably derived from pellos, ‘dark-coloured’), into livia, derived from the Latin livens (‘lead-coloured’), ultimately from livere (‘being bluish’).

Wild rock pigeon, resting on the wall of a ruined fort, Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dovecote, Hanoi Botanical Garden, Vietnam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This form of the domestic pigeon is called white peacock pigeon. – Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

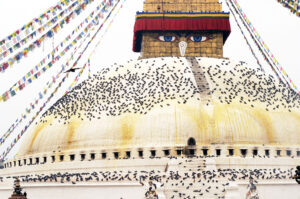

Every morning, numerous feral pigeons are being fed in Kathmandu, Nepal, here around the Buddhist Bodhnath Stupa (top), and on Durbar Square. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This feral pigeon is sitting in a hole in a wall in the city of Ragusa, Sicily, presumably its breeding place. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pigeon racing is a popular sport in Taiwan. This abandoned dovecote in the city of Taichung is applied with spikes to prevent raptors from landing on the roof. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Uploaded September 2017)

(Latest update October 2024)