Ancient and huge trees

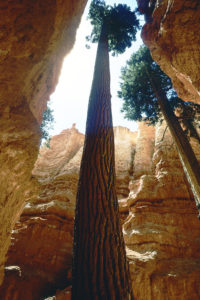

Magnificent trunks of coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens), soaring towards the sky, Humboldt Redwood State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

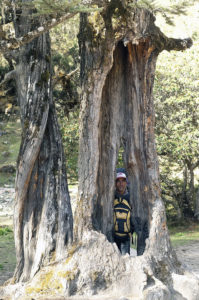

People, gathered at the foot of a huge tree, Myanmar. Many women and children in Myanmar smear a white paste, called thanaka, in their face to protect the skin against the sun, and it also makes the skin smooth. This paste is made from branches of the orange jessamine tree (Murraya paniculata). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

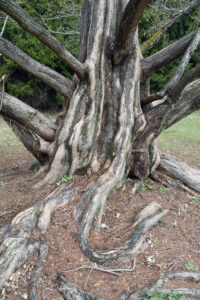

Planted row of ancient cypresses, near Manchester, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

For some reason or other, this stump of a giant tree has been allowed to remain in the middle of agricultural land near Ohakune, New Zealand. The stump ’lives’ on, as several bushes have taken root in its top. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Chinese Hemlock Nature Trail leads through montane monsoon forest in Taipingshan National Forest, eastern Taiwan. In this picture, the trail is passing beneath the roots of an ancient tree. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The root net of a toppled conifer, photographed with a very wide-angled lens, Stora Sjöfallet National Park, Lapland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In 1902, when the Long Bien railway station in Hanoi, Vietnam, was built, this tree was spared, and the roof was built accordingly. Since then it has grown to huge dimensions, and today it functions as a Buddhist shrine inside the waiting hall. The areial roots of a strangler fig (Ficus) are wrapped around its trunk. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fungi, growing on the trunk of a burned forest tree, Silent Valley National Park, Kerala, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

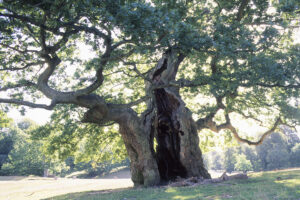

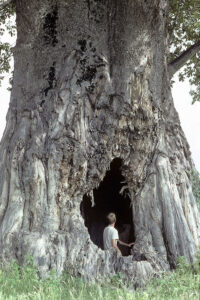

Old and giant trees appeal to most people. Standing under a huge, gnarled trunk, thousands of years old, makes the majority of us feel very humble indeed.

In the old days, however, most people had an entirely different view of these giant beings. Everywhere on the planet, huge tracts of thousand-year-old forests were ruthlessly cut down by the lumber industry, or to make way for farming or urbanization. Numerous examples of this destructive behaviour are described on the page Folly of Man.

Even today, there are well-educated people who do not appreciate old trees. Danish author Thorkild Bjørnvig (1918-2004) once told me about an incident, which took place on his residential island, Samsø. One of the residents in the local community lived in a farmhouse, in front of which grew an enormous old horsechestnut tree (Aesculus hippocastanum). One day, Bjørnvig noticed that the tree had disappeared, and he asked the owner why. This was his answer: “For a long time, that tree has been a thorn in my flesh!”

Below, a number of trees are described, presented in alphabetical order according to family, genus, and species.

Altingiaceae

This family was named for the genus Altingia, which is now regarded as a synonym of Liquidambar – the only present genus in the family.

Liquidambar Sweetgum

A genus of 15 species of large, deciduous trees, 25-40 m tall, with palmately lobed leaves, which have a pleasant aroma when crushed. The leaves often attain brilliant colours in autumn and winter, including bright red, orange, yellow, and purple. Pictures depicting such leaves are shown on the page Autumn.

The fruit is a globular, woody capsule, to 4 cm across, covered in prickles, presumably an adaptation to being attached to the fur of animals, which then spread the seeds in this way. Pictures depicting the capsules are shown on the page Plants: Burs.

These plants were formerly placed in the witch-hazel family (Hamamelidaceae), but has now been transferred to Altingiaceae. They are found from north-eastern India eastwards to China, Taiwan, and Korea, and thence southwards through Indochina to Sumatra and Java, and also in the eastern United States, Mexico, and Central America, with an isolated species in south-western Turkey and on Rhodes. Several species are cultivated elsewhere as ornamental trees.

The generic name is derived from the Latin liquidus (‘fluid’) and the Arabic anbar, which, via the Moors, became ambar in Spanish and amber in English. The generic and common names both allude to the fragrant sap of several species of the genus, which was formerly used in the cosmetic industry.

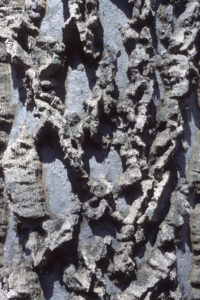

Liquidambar styraciflua American sweetgum

This species, also known by a number of other popular names, including hazel pine, bilsted, redgum, satin-walnut, and alligator-wood, is native to south-eastern United States, and is also found in montane areas of southern Mexico and Central America. The leaves are almost star-shaped, with 5 to 7 pointed lobes, and the fruits are ball-shaped, hard, and spiky. A picture, depicting the colourful autumn foliage, is shown on the page Autumn.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘flowing with storax’ (a plant resin), like the generic name alluding to the gum.

A close relative, Chinese sweetgum (L. formosana), is presented on the page Autumn.

Deeply furrowed and corky bark of sweetgum, Point of Rocks Park, Richmond, Virginia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anacardiaceae Sumac family

Dracontomelon duperreanum Indochina dragonplum

An evergreen tree, to 20 m tall, with buttresses. The bark often peels off in flakes, creating a beautiful pattern on the trunk. The leaves are pinnately divided, with 11-15 alternate, oblong leaflets. Inflorescences are panicles with small bluish-white, bell-shaped flowers. The fruit is a globular yellow drupe, to 4 cm across.

It is distributed in southern China and northern Indochina, growing in forests up to elevations around 350 m.

The fruits are much utilized in the Vietnamese cuisine, as souring agent, or cooked with duck. After being preserved in sugar, it can be used to make a cooling drink.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek draco (‘dragon’) and melon (‘apple’), referring to the fruit.

Indochina dragonplum, Hanoi Botanical Garden, Vietnam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pistacia Pistachio trees

This genus, comprising about 11 species, is native to southern Texas, Mexico, Central America, southern Europe, northern and eastern Africa, and from the Middle East eastwards to China, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

The generic name is derived from pistakia, the Ancient Greek name of the true pistachio tree (P. vera).

Pistacia chinensis Chinese pistachio tree

This small tree is native from Afghanistan eastwards to Myanmar, China, and Taiwan, and thence southwards to the Philippines. A disjunct population is found in the Caucasus.

Due to its hardiness, and the attractive autumn foliage, it is widely cultivated in temperate and subtropical areas around the world. In warmer areas, it sheds the leaves in mid-winter. Pictures, depicting this winter foliage, are shown on the page Autumn.

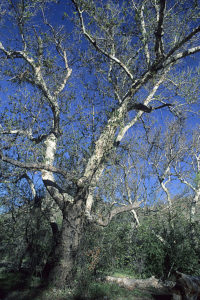

Chinese pistachio tree is very commonly planted in parks and along streets in Taiwanese cities. This picture shows an old tree with peeling bark, Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Apocynaceae Dogbane family

Alstonia

A genus of evergreen trees and shrubs with about 45 species, distributed in tropical regions of Africa and Asia, New Guinea, Australia, Mexico, and Central America, with a core area in Malaysia and Indonesia. Some of the species grow very large, for instance A. pneumatophora, which may reach a height of 60 m, with a trunk diameter over 2 m.

The generic name honours Charles Alston (1685-1760), professor of botany in Edinburgh.

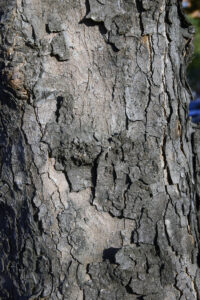

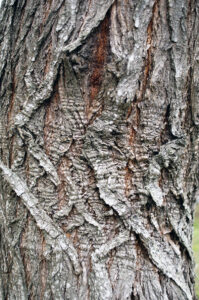

Alstonia scholaris Blackboard tree

This tree, also known by several other names, including devil tree, milkwood-pine, and white cheesewood, is found in mixed forests, from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to south-western China, and thence southwards through Indochina, the Philippines, Indonesia, and New Guinea to northern Australia.

It grows to 40 m tall, with greyish bark, and young branches have numerous lenticels. The leaves, arranged in whorls of 3-10, are glossy-green above, greyish below, obovate, to 23 cm long and 8 cm broad, tip usually rounded. Flowers are white, tubular, to 1 cm long, in dense clusters. The fruit is a pod-like follicle, very narrow, to 40 cm long.

The bark contains a very bitter, milky sap. Bark and leaves are utilized medicinally for headache, influenza, bronchitis, and pneumonia, and the wood is used for making coffins.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘relating to schools’, alluding to the former usage of the wood for blackboards.

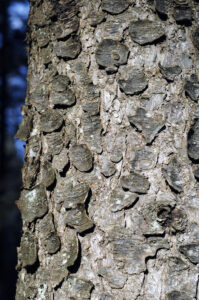

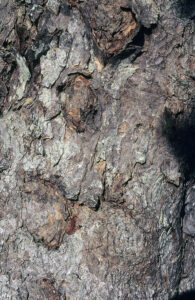

Bark of a huge blackboard tree, Taichung, Taiwan. According to Kew Gardens, this species is not native to Taiwan, but it is very commonly planted on the island. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Aquifoliaceae Holly family

Ilex Holly

This is the sole genus of the family, comprising about 480 species of evergreen or deciduous trees, shrubs, or climbers, distributed almost worldwide. The fruit is a berry-like drupe, containing 1 or 2 nuts.

In Ancient Rome, ilex was the name of the holm oak (Quercus ilex). In 1753, Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) adopted this name as the generic name of hollies, probably due to the similarity of the leaves of the common holly (Ilex aquifolium) to those of the holm oak. The ancient name of holly was acrifolium, from Proto-Italic akris (‘sharp’) and the Latin folium (‘leaf’), which was later changed into aquifolium.

Ilex opaca American holly

A medium-sized evergreen tree, usually below 20 m high, but may occasionally grow to 30 m. The trunk diameter is less than 50 cm in most individuals, but may sometimes be up to 1.2 m. The leaves are quite similar to those of the common holly, but less glossy.

It is native to the eastern United States, from Massachusetts and southern New York State southwards to northern Florida, and thence westwards to eastern Oklahoma and eastern Texas.

The specific name is Latin, meaning either ‘growing in the shade’ or ‘giving shade’.

Trunk of an old American holly with lichens, Fire Island, Long Island, New York State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Araucariaceae Araucaria family

Agathis Kauri trees

Kauris, together with members of the genus Araucaria (below), belong to an ancient group of trees, which first appeared during the Jurassic period (190 to 135 million years ago).

Mature trees have straight trunks, in some species to 60 m tall, with little or no branching below the crown. The bark is smooth, pale grey or grey-brown, usually peeling into irregular flakes. Young leaves are often a coppery-red, varying in shape from ovate to lanceolate, whereas older leaves are green, elliptic to linear, leathery and thick. Female cones are huge, ovate or globular, maturing after 2 years.

These trees, altogether 17 species, are found in Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, New Guinea, north-eastern Australia, and New Zealand.

Several species yield resin, called kauri gum. The durable timber is excellent for boat-building, and to make guitars and other items.

The generic name is Latin, denoting something notable or precious, derived from Ancient Greek agathon (‘a good thing’), originally from agathos (‘good’).

Agathis australis Southern kauri tree

This iconic species is restricted to the northernmost part of New Zealand’s North Island. It is among the world’s largest trees, growing to over 50 m tall, with trunk girths up to 16 m. Although their age is difficult to estimate, it is believed that they may live for more than 2,000 years.

Today, the largest kauri is found in Waipoua Forest. It is called Tane Mahuta (‘Lord of the Forest’), which refers to Tane, the Maori god of trees and birds. The height of this majestic tree is c. 46 m, its girth is about 15.5 m, and its volume is estimated at 516 m3. In the past, even larger specimens were known. The largest on record, called The Great Ghost, was about 8.5 m in diameter, with a girth of c. 26.9 m. It was consumed by fire around 1890.

When the Maoris settled in New Zealand about 700 years ago, small-scale usage of kauri began. The timber was utilized to construct houses and boats, and for carving. Kauri trees exude a gum through cracks in the trunks, and, over the years, large quantities are built up in the soil beneath the trees. The Maoris used this gum to start fires, and also for chewing, after it had been soaked in water and mixed with the milky juice of common sow-thistle (Sonchus oleraceus).

A full-scale destruction of these magnificent forests began with the arrival of Europeans in the 1700s and 1800s. Sailors found that the trunks of young kauri were ideal for ships’ masts and spars, and settlers utilized the high-quality timber of mature trees for construction. Kauri gum was also used at a large scale to manufacture varnishes and other products. The gum was obtained through digging or, more destructively, by bleeding live trees. Large areas of kauri forest were also cleared for farmland until as late as the mid-1900s.

It has been estimated that kauri forests once covered between 10,000 and 15,000 km2. Today, a tiny fraction, c. 70 km2, exists, corresponding to 0.5% of the original extent.

Now the kauri is facing a new threat, called kauri dieback. This disease is caused by a fungus, Phytophthora agathidicida, which attacks the trees through their shallow root system, eventually causing their death. There is no known cure for this disease, and its spread can only be reduced by avoiding trampling near kauri roots. (Source: doc.govt.nz/nature/native-plants/kauri)

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘southern’.

The largest known kauri is Tane Mahuta (‘Lord of the Forest’), which may be more than 1,500 years old. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Araucaria

This genus contains 20 species, which occur in Chile, Argentina, and southern Brazil, in New Guinea and eastern Australia, and on a number of islands in the south-western part of the Pacific. No less than 14 species are endemic to New Caledonia.

Most species are large, with a massive, erect trunk, in some species reaching a height of 80 m. The branches grow in whorls, covered in leathery or needle-like leaves. Female cones are globular, the largest ones to 25 cm across. They contain up to 200 large, edible seeds. Male cones are cylindric, to 10 cm long and 5 cm wide.

The generic name was derived from the name of a Chilean tribe, the Araucanians, who ate the seeds of Araucaria araucana (below).

Araucaria araucana Pehuén, Chilean monkey-puzzle tree

Grand forests of this tree are ubiquitous in Conguillio National Park and a few other places in the Andes. Elsewhere, it is endangered. It is described in depth on the page Travel episodes – Chile 2011: The white forest.

Forest of pehuén, Conguillio National Park, Chile. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This gigantic pehuén, called Araucaria Madre (‘Mother of monkey-puzzle trees’), is about 1,800 years old, 50 m tall, and has a diameter of c. 2.1 m. – Conguillio National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Arecaceae Palms

Jubaea chilensis Chilean palm

This stately tree, the only member of the genus, is endemic to a small area in central Chile. It may grow to 25 m tall, with a very thick trunk, sometimes up to 1.3 m in diameter. The dark green leaves are pinnate, to 5 m long, with pinnae to 50 cm long.

In a botanical context, a juba is a loose panicle, whose axis falls to pieces. Perhaps this is the case in this species. However, the name may also refer to King Juba II (c. 50 B.C. – 19 A.D.) of Numidia (in present-day Algeria and Tunisia), who had a great interest in plants and often described them.

A stronghold of the Chilean palm is La Campana National Park, where these pictures were taken. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Phoenix Date palms

A genus of 14 species, distributed from the Canary Islands and Africa across the Middle East, Arabia, and the Indian Subcontinent to Indochina and southern China, and thence southwards to the Philippines and Indonesia.

The generic name is derived from phoinikos, the Greek word for the cultivated date palm (P. dactylifera), used by Greek scholar and botanist Theophrastos (c. 371-287 B.C.), and also by Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder (23-79 A.D.). It may refer to the Phoenicians, or to Phoenix, son of Amyntor and Cleobule in Homer’s Iliad, or to the phoenix, the sacred bird of Ancient Egypt. (Source: U. Quattrocchi 2000. CRC World Dictionary of Plant Names)

Phoenix canariensis Canary Islands date palm

As its name implies, this species is endemic to the Canary Islands. It grows to 20 m tall, occasionally to 40 m, with pinnate leaves to 6 m long and with 80-100 leaflets on both sides of the central rachis. The fruit is an ovoid, yellow to orange drupe, to 2 cm long. It is edible, but not very tasty.

Old Canary Islands date palm, Barranco Mogán, Gran Canaria. The withered leaves, which remain on the trunk for several years, have been chopped off. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Washingtonia American fan palms

A small genus with only 2 species of fan palms, W. filifera, which is native to the Mohave and Colorado Deserts in southern California, northern Baja California, a few places in south-western Arizona, and W. robusta, which is endemic to north-western Mexico.

The generic name was given in honour of George Washington (1732-1799), the first president of the United States (1789-1797).

Washingtonia filifera California fan palm

An impressive fan palm, to 20 m tall, with a trunk diameter up to 1 m, and numerous huge, terminal, fan-shaped leaves, which may grow to 4 m long, with leaflets to 2 m. The leaf-stalk, to 2 m long, is heavily armed with sharp thorns. The inflorescence is huge, to 5 m long, with masses of white flowers, maturing into small blackish-brown drupes, to 1 cm across, with a thin layer of sweet flesh over a single seed.

The scattered growths thrive in oases with springs, but may also be found in drier areas.

California fan palms with hanging ‘bags’ of old leaves, Oasis of Mara, Joshua Tree National Park, California. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Betulaceae Birch family

Alnus Alder

This genus, comprising about 40 species of shrubs or trees, is distributed throughout the northern temperate zone, with a few species in Central America and the Andes. The fruits are very distinctive, woody, resembling diminutive cones.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of alders. Some authorities connect the name with High German elo (’greyish-yellow’), and with Sanskrit aruna (’reddish-yellow’), referring to the fact that the wood of common alder (below), when cut, assumes a bright reddish-brown colour. The common name evolved from the Old English word for these trees, alor, which in turn derived from Proto-Germanic aliso.

Alnus glutinosa Common alder

Also known as black alder, this species is native to the major part of Europe, south-western Asia, and northern Africa. It thrives in wet locations, living in symbiosis with a nitrogen-fixing actinomycete bacterium, Frankia alni. These bacteria cause the growth of coral-like nodules on the roots of the trees, inside which thick-walled cells are formed, housing the bacteria. Protected here against the harmful oxygen of the air, the bacteria change nitrogen into nitrates, which can be utilized by the alder trees. This is the reason that these trees are able to grow in oxygen-poor soils. The nitrates enrich the soil, making it possible for other plants to grow in these poor soils.

The specific name is derived from the Latin gluten (’glue’), alluding to the glutinous leaf buds and newly opened leaves.

Trunk of an ancient common alder, Funen, Denmark. Note the ceramic insulator to the right, almost overgrown by bark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

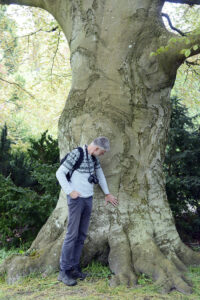

Lars Skipper, admiring an old common alder, growing at the shore of Lake Mossø, central Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A row of old alders along Gudenåen River, central Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Betula Birch

A genus with 50-60 species, distributed in temperate and subarctic areas of Europe, Asia, and the Americas. Male and female flowers are borne in catkins, in separate inflorescences, males pendulous, females erect. The fruit fragments into 3-lobed scales and winged nutlets when mature.

In Norse religion, the birch represented Freya, the Great Mother Goddess, and among Celtic peoples the star goddess, Arianrhod, whose caer (‘throne’) was situated in the Corona Borealis (Northern Lights). She was invoked through the birch to assist in births and initiations.

Previously, the soft birch wood was carved into numerous items, including furniture, cups, bowls, bobbins, cradles, and toys. The bark separates into thin strips, which peels off easily. It is tough, water proof and rot proof, making it perfect as roofing material. It was also utilized to make buckets, baskets, bottles, plates, and shoes, and for writing and drawing. Due to its content of volatile oils, rolled-up bark could be used as torches.

Danish author and artist Claus Bering (1919-2001) once sat on his terrace, writing, and from a large birch tree a lot of seeds and seed scales blew into his hair and his coffee. He was curious to know how many seeds a big birch tree like that would produce, so he chose a twig with average fertility. There were 12 female catkins on it. He plucked these 12 catkins, pulled them apart, and counted the number of seeds in each of them. On average they contained 350 seeds. Then he counted the number of branches on the tree, about 50, each having on average 32 twigs. Now the calculation was simple: 50x32x12x350 = 6.720.000 seeds. An impressive number!

The generic name is derived from Celtic betu (’glue’), referring to the fact that Celts extracted a glue-like substance from birch sap. In certain areas with Gaelic-speaking peoples, including Wales and Brittany, birch is still called bezuenn or bedwen. The name birch is derived from Proto-Germanic berko, in all probability rooted in Sanskrit bhurja, the name of a species of birch.

Betula alleghaniensis Yellow birch

This tree is widely distributed in south-eastern Canada and eastern United States, found from Minnesota eastwards to Newfoundland, southwards to Tennessee and northern Georgia. It is the provincial tree of Quebec.

It is a medium-sized, deciduous tree, growing to about 24 m tall, occasionally to 30 m, with a trunk diameter to 0.9 m, making it the largest North American birch species. It often becomes about 150 years old, and some specimens to 300 years have been reported.

The specific name alludes to the Allegheny Mountains, a part of the Appalachians, whereas the common name refers to the yellowish bark of this species.

The bark of this old yellow birch is peeling off in small strips, Kenoza Lake, Haverhill, Massachusetts. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Betula lenta Sweet birch, black birch

A medium-sized, deciduous tree, usually below 24 m tall, occasionally to 30 m and rarely to 35 m, with a trunk diameter up to 60 cm. On older trees, the bark cracks into irregular, scaly plates. The oldest known specimen was about 370 years old.

It is found from southernmost Ontario and southern Maine southwards through New England and the Appalachian Mountains to northern Georgia and Alabama.

The common name refers to the sap that can be tapped to make syrup. It is stronger than maple sap, and is mainly used to make birch beer. The inner bark may be eaten raw, but has been labelled ’emergency food’. Tea can be made from twigs and inner bark.

Peeling bark of an old sweet birch, Winnikenni Park, Haverhill, Massachusetts. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Betula papyrifera Paper birch

Paper birch with the snow-white bark is a medium-sized, deciduous tree, often growing to 20 m tall, occasionally to 40 m, with a trunk diameter up to 75 cm. The leaves are doubly serrated, with sharp teeth. It is a pioneer species, which often takes over an area that has burned or been cleared of other trees.

It is widely distributed in subarctic areas of North America, southwards to northern Montana, the Great Lakes area, and New England. It is the provincial tree of Saskatchewan and the state tree of New Hampshire.

The specific and common names refer to the fact that paper can be produced from the wood, which also make sexcellent firewood. The sap may be boiled down to produce syrup, which has a sugar content of about 1%.

Large paper birch, covered in frozen rain, Freeport, Maine. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Betula pendula Silver birch, warty birch

This species is very widespread and common in Eurasia, from Norway, Ireland, and Spain eastwards to eastern Siberia and Japan, southwards to the Balkans, Turkey, the Caucasus, Kyrgyzstan, and China. It has also been introduced to North America, where it is considered invasive in some parts. It forms forests in many regions, but may also grow singly in open areas.

It is typically between 15 and 25 m tall, occasionally to 30 m, the trunk usually under 40 cm across at breast height. The bark is golden-brown at first, later turning to white and peeling off in flakes. The base of old trees has numerous corky fissures. The twigs are slender and often pendulous, giving rise to the specific name. The leaves are heart-shaped, long-pointed, margin doubly toothed. They turn a lovely yellow in autumn.

The name silver birch refers to the white bark, which peels off in strips, whereas the name warty birch alludes to the twigs having a rough surface due to numerous resinous ‘warts’.

Old silver birch, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

As silver birches age, the colour of the bark on the lower part of the trunk changes from almost pure white to blackish. This one was encountered in central Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Weeping birch is a cultivated form of silver birch with hanging branches. This old specimen is in the garden of the Boller Estate, near Horsens, Denmark. Ivy (Hedera helix) is climbing up the trunk. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Betula pubescens Downy birch

This species resembles silver birch (above), but may be identified by the downy twigs and leaf-stalks, margin of the leaves is singly, not doubly toothed, and the twigs are not hanging. Almost all older individuals are infested with a fungus, Taphrina betulina, which causes twigs to form large galls, popularly called witches’ brooms.

It is likewise widespread and common in Eurasia, but is more northerly, found from Iceland, Ireland, and Portugal eastwards to eastern Siberia, southwards to the Caucasus, northern Iran, and southern Siberia.

The specific name is derived from the Latin pubes (’downy’), like the common name alluding to the downy twigs.

In former days, birch populations in Arctic regions were regarded as a subspecies, tortuosa, of the downy birch. However, genetic research indicates that it evolved from hybridization between downy birch and dwarf birch, and today most authorities regard it as a variety of the former, named B. pubescens var. pumila.

Bark of an old downy birch, Ismanstorp, Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Betula utilis Himalayan birch

This large deciduous tree may grow to 35 m tall, but is much smaller and shrub-like at higher altitudes. It is easily identified by its white, brownish, or reddish bark, which peels off in very thin horizontal flakes. Lenticels are very numerous on trunk and branches. Branches red-brown, smooth, twigs downy, with dense resinous glands. The stalked leaves are ovate or oblong, smooth above, with resinous glands, to 10 cm long, 6 cm broad, woolly-hairy beneath when young, margin irregularly saw-toothed, tip pointed.

Inflorescences are yellowish, male catkins slender, to 10 cm long, appearing before the leaves. Female catkins are solitary or 2-3 together, to 5 cm long and 1.2 cm broad when in fruit. The nutlet is ovoid or ellipsoid, to 3 mm long, with membranous wings to 3 mm wide.

This species is very common in mountains, from Afghanistan eastwards to western China, often forming pure stands at altitudes between 2,500 and 4,300 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘useful’. Locally, the wood is used for building construction and as firewood. The bark is used as roof cover, and to make paper, and is also burned as incense. A paste of the bark is utilized for wounds and burns, a decoction of the bark for jaundice and earache, a paste of the resin for boils, and also as a contraception remedy. The foliage is lopped for fodder.

The reddish bark of Himalayan birch peels off in large, thin flakes. These older trees were encountered near Kyangjuma, Khumbu, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Carpinus Hornbeam

A genus with about 50 species of deciduous trees, distributed in Asia, Europe, and the Americas. No less than 27 species are endemic to China. Previously, this genus was placed in the now defunct family Corylaceae.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of hornbeams, probably derived from Proto-Indo-European kar (‘hard’), alluding to the hard wood of these trees. The common name is from Middle English hernbem, hern– of uncertain meaning and origin, bem a corruption of the German baum (‘tree’).

Carpinus betulus Common hornbeam

A medium-sized tree, often to 25 m tall, sometimes to 30 m, with smooth, greyish bark. Leaf buds are to 1 cm long, pressed close to the twig. The leaves resemble those of the common beech (Fagus sylvatica), to 9 cm long, with serrated margin. Male and female catkins appear after the leaves, pollination is done by wind. The fruit is a small nut, to 8 mm long, partially surrounded by a leafy involucre, to 4 cm long.

This species is found in the major part of Europe, from England, Denmark, and southern Sweden southwards to the Mediterranean, eastwards to western Russia, the Caucasus, and northern Iran.

The hard wood was formerly utilized for various items, including cog wheels in mills, pulleys on sailing ships, bottoms of planers, shoe trees, and hammers in pianos. Today, it is mostly used as excellent, slow-burning firewood.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘birch-like’, alluding to the catkins, which resemble those of birch trees (Betula).

The furrowed bark of an old hornbeam, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Corylus Hazel

A genus with about 16 species of deciduous trees and large shrubs, widely distributed in Europe, from Ireland and Portugal eastwards to the Ural Mountains, and from Scandinavia and Finland southwards to the Mediterranean, the Caucasus, and Iran, in eastern Asia, from north-eastern China southwards to northern Indochina and the Himalaya, and in North America, from southern Canada southwards to southern United States.

Hazels have simple, rounded leaves with double-toothed margins. The flowers appear very early in spring, before the leaves. Male catkins are pale yellow, to 12 cm long, whereas the female catkins are very small, largely concealed in the buds, with only the bright-red, small styles protruding. The fruit is a nut, to 2.5 cm long and 2 cm wide, surrounded by a large, leafy involucre, called a husk, which encloses the nut partly or fully, depending on the species.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for hazel trees.

Previously, this genus was placed in the now defunct family Corylaceae.

Corylus avellana European hazel

This tree is found in the major part of in Europe, from Ireland and Portugal eastwards to the Ural Mountains, and from Scandinavia and Finland southwards to the Mediterranean, the Caucasus, and the Alborz Mountains in northern Iran.

Usually, it is a large shrub to about 10 m tall, sometimes to 15 m, typically with many slender trunks clustered together. It prefers sunny places, and specimens in forests are often low and stunted. The ovoid nut, to 2 cm long, is partly covered by the husk.

The specific name was given by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), who took this name from De historia stirpium commentarii insignes, published by German physician and botanist Leonhard Fuchs (1501-1566) in 1542, in which it was described as Avellana nux sylvestris (‘forest nut of Avella’, a town in southern Italy). In turn, that appellation was taken from Naturalis Historia, by Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder (23-79 A.D.).

The succession of a wild growth of common hazel is described on the page Nature Reserve Vorsø: Expanding wilderness.

The base of an ancient European hazel, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Numerous trunks of an old European hazel, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Casuarinaceae Ironwood family

Casuarina Ironwood, she-oak

This genus, comprising about 14 species of trees, is native to the Indian Subcontinent, Indochina, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, New Guinea, Australia, and islands in the Pacific. Several species have been planted, or accidentally introduced, in many other places, where they easily become naturalized, and some species are now often regarded as invasive plants.

Photosynthesis of these plants is done by the green, soft, pendulous branchlets, and the leaves are reduced to scales, arranged in whorls of 5 to 20 around the branchlets. Male flowers are in spikes along the branchlets, whereas the female flowers sit in spikes on short flower-stalks, which look different from the true branchlets. The fruit is small and cone-like.

The generic name is derived from Casuarius, the Latin name of cassowaries, due to the resemblance of the branches to the feathers of these birds. Both common names refer to the durable wood of these trees. The strange term she-oak arose, when the quality of the timber was equaled to that of the English oak (Quercus robur).

Casuarina equisetifolia Coastal ironwood

This species is usually below 12 m tall, but may reach a height of 35 m under favourable conditions. The greyish bark is smooth on younger trees, but deeply furrowed on old trees. The branchlets may grow to 30 cm long.

It has about the same distribution as that of the genus, but has become naturalized in many countries and is considered a pest in Florida, Bermuda, and Hawaii.

The specific name means ‘with foliage like Equisetum’ (horsetail), which is somewhat erroneous, as the leaves of this plant are reduced to scales. It must be admitted, however, that the twigs look like horsetail plants.

Coastal ironwood has been extensively planted on Cretan beaches. This ancient specimen was observed on Preveli Beach. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This row of white-painted coastal ironwood trees was observed on the Rodopos Peninsula, Crete. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Celastraceae Bittersweet family

Euonymus Spindle tree, burning-bush

A large genus with about 130 species of deciduous or evergreen shrubs, small trees, or climbers. The fruit is a globular capsule, pink or white, which splits open to reveal the seeds, which are covered by a fleshy, orange or red layer. This fleshy layer attracts birds, which eat it, thereby dispersing the seeds in their droppings.

Most species are native to eastern Asia, with 50 species endemic to China. Others occur in Europe, northern Africa, Madagascar, Indonesia, New Guinea, eastern Australia, North America, Mexico, and Central America.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek eus (‘good’) and onoma (‘name’). It is not clear why Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) applied this name to this genus. The name spindle tree stems from the former usage of the hard wood of the European spindle tree (below) to make spindles for wool-spinning, whereas the name burning-bush refers to the brilliant autumn foliage of several species.

Euonymus europaeus European spindle tree

This is a small tree, rarely reaching a height of 10 m, with a trunk to 20 cm across. It is widely distributed in Europe, from the British Isles, southern Scandinavia, and the Baltic countries southwards to the Mediterranean, eastwards to central Russia and the Caucasus. It mainly grows at forest edges.

The gorgeous fruits are red, pink, or purplish capsules, opening late in the autumn to reveal the black seeds, which are coated with a fleshy orange layer. These fruits look very inviting indeed, but the seeds contain highly toxic alkaloids, and several cases of poisoning of children have been reported.

The wood of this species is very hard and was formerly used to make butchers’ skewers and spindles for wool-spinning.

A close relative, the eastern burning-bush (E. atropurpureus), is presented on the page Autumn.

This old spindle tree has toppled, but is still full of life, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Combretaceae Leadwood family

Terminalia Tropical almonds

A huge genus of large trees, counting about 280 species, distributed in tropical and subtropical regions around the world.

The generic name is from the Latin terminus (‘end’), referring to the fact that the leaves appear at the very tips of the shoots. Despite the common name, these plants are not even distantly related to the true almond (Prunus amygdalus). The name alludes to the fruits, which resemble almonds.

Several pictures, depicting the glorious winter foliage of the Indian almond (Terminalia catappa), are shown on the page Autumn.

Terminalia myriocarpa East Indian almond

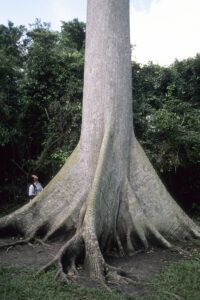

This tree is typically between 15 and 25 m tall, but may grow to huge dimensions, to a height of 40 m, with a diameter up to 4 m, and with large buttresses, sometimes to 5 m tall. The bark is grey and smooth, flaking with age. The leaves are elliptic, to 20 cm long, dull green, finely toothed along the margins. The flowers are small, pale yellow, in slender, terminal clusters. The fruit is small, initially green, becoming bright pink when mature.

It is distributed in forests, from eastern Nepal eastwards to southern China, and thence southwards through Indochina to Sumatra. In the Himalaya, it may be found up to elevations around 1,700 m.

It is sometimes cultivated as an ornamental. The wood is used as timber for construction of houses, floors, and boats.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek myrios (‘ten thousand’) and karpos (‘fruit’).

This magnificent East Indian almond in Cuc Phuong National Park, Vietnam, has been dubbed ‘Thousand-year-old tree’. Mosses and algae are growing on the trunk. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cupressaceae Cypress family

Calocedrus Incense-cedars

A small genus of 4 conifers, one native to western North America, 3 to eastern Asia.

These trees are rather closely related to members of the genus Thuja (below), with similar overlapping scale-like leaves, but the leaves are in what looks like whorls of 4 (in reality 2 x 2), not evenly spaced apart as in Thuja, instead with the successive pairs closely, and then distantly spaced. Calocedrus cones have only 2-3 pairs of erect scales, rather than 4-6 pairs of very thin scales in Thuja.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kallos (‘beautiful’), and Cedrus, the generic name of true cedars (see below under Pinaceae).

Calocedrus decurrens Californian incense-cedar

Formerly called Libocedrus decurrens, this large conifer, growing to about 57 m tall, may have a trunk diameter up to 3 m. Before settlers started logging at a large scale, trees reportedly reached 69 m, with a diameter of 4 m. It grows very slowly, but can reach an age of more than 500 years.

It is distributed from Oregon southwards through California and western Nevada to northern Baja California.

Indigenous tribes utilized it for numerous purposes, the bark to construct temporary conical-shaped huts and also more permanent houses, and to produce fire by friction. Hunting bows and baskets were made from thin branches. It was also used medicinally for stomach problems.

On old incense-cedars, the bark is deeply furrowed and up to 15 cm thick. This old specimen was photographed in Kings Canyon National Park, Sierra Nevada, California. The small holes in the bark were probably drilled by a sapsucker (Sphyrapicus). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chamaecyparis False cypresses

A genus of about 6 species of evergreen conifers, 2 in Japan, 2 in Taiwan, one in eastern United States, and one along the Pacific coast, from California north to Washington. Full-grown trees vary in size from 20 to 70 m. Individuals up to a year old have needle-like leaves, whereas older specimens have scale-like leaves. The cones are globular or ovoid, with 8-14 scales, each bearing 2-4 small seeds.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek khamai (‘near the earth’) and kyparissos (‘cypress’) – an odd name, considering that some of these trees can attain heights of 70 m.

Two species are native to Taiwan, the red false cypress and the yellow false cypress, both presented below.

Following the Sino-Japanese war of 1894, Taiwan was ceded to Japan and became a Japanese colony. In 1912, the Japanese government began large-scale logging of false cypresses in the Alishan area, and where the Alishan Mountain Railway today passes through areas at higher elevations, cypress forests once covered the entire landscape.

Soon, the forests on Taiping Shan, Ilan County, and Pahsien Shan, Nantou County, were also opened up for logging, and later also many other areas. An endless stream of cypress logs flowed out of the mountains, to be transported across the sea to Japan, where they were used for various purposes, including pillars for Shinto shrines.

Early surveys estimated that, before logging began, about 20 million ancient false cypresses were found in Taiwan. Of the approximately 300,000 false cypresses at Alishan, which were more than 1,000 years old, all that remains today is a few giant trees, scattered among introduced Japanese red cedar (Cryptomeria japonica).

Large-scale logging of these magnificent trees was continued, even after the Japanese left Taiwan in 1945 – in fact, right up to 1989. Today, the only larger areas of ancient false cypresses are forests on Hsiukulan Shan, central Taiwan, and on Chilan Shan, Ilan County. (Source: Chang Chin-ju, Ancient Giants of the Forest – Taiwan’s False Cypresses)

Chamaecyparis formosensis Red false cypress

A magnificent tree, endemic to Taiwan, where it grows in the central mountains in areas of high precipitation, at elevations between 1,000 and 2,900 m.

This species is slow-growing, but when left in peace it may live for at least 2,000 years and grow to enormous dimensions, to 60 m tall with a trunk diameter up to 7 m. The bark is reddish-brown, vertically fissured. Adult leaves are scale-like, to 3 mm long, tip pointed, green above and below, with an inconspicuous band of pores at the base, in which respect it differs from yellow false cypress (below). Leaves on young plants are needle-like, to 8 mm long, soft and bluish-green. The cones are ovoid or oblong, to 1.2 cm long and 8 mm across.

It is threatened by habitat loss and excessive felling for its valuable timber.

In 1544, when the Portuguese first saw Taiwan from the sea, they named it Formosa (‘beautiful’). Since then many plants and animals, which were described from specimens collected on the island, were named various forms of this word.

The oldest and largest red cypress in Alishan National Forest, about 2,000 years old, height 43.5 m, circumference 13 m. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red cypress, c. 1,000 years old, Alishan National Forest. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These red cypresses in Alishan National Forest are called ‘Three Generations Trees’. The first generation is a decayed trunk, lying on the ground. A seed sprouted in this trunk and lived for several hundred years before dying. A third tree has sprouted in the remains and is now a vigorous tree. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stump of an old red cypress, Alishan National Forest. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The lower part of the trunk of an ancient red cypress, Dasyueshan National Forest. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Two red cypresses in Yushan National Park, named the Fuci Trees, were killed by a forest fire in 1963. The dried-out trunks remained standing for many years, but one of them fell in 2019. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This trail in Alishan National Forest has been worn by so many visitors’ feet that the roots of a red cypress has appeared on the surface. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chamaecyparis taiwanensis Yellow false cypress, Taiwan cypress

This tree, by many authorities regarded as a subspecies, formosana, of Japanese false cypress (C. obtusa), is native to the mountains of Taiwan, where it grows in areas of high rainfall and air humidity, at altitudes between 1,300 and 2,800 m, whereas C. obtusa is primarily found on drier mountain tops.

Yellow false cypress grows to 40 m tall, with a trunk diameter up to 2 m. The bark is reddish-brown, vertically fissured. Older leaves are scale-like, to 1.5 mm long, green above and below, the underside with a white band of pores at the base, in which respect it differs from red false cypress (above), tip acute (unlike the blunt tip on leaves of C. obtusa). Leaves on seedlings are needle-like, to 8 mm long. Female cones are globular, to 9 mm across (smaller than those of C. obtusa).

An essential oil, named Taiwan Hinoki, is obtained from twigs and wood. This oil is valued for its ability to kill harmful bacteria, viruses, and fungus. It is also excellent for respiratory problems, blocked sinuses, high blood pressure, and skin diseases. Research indicates that its fragrance can effectively release tension and stress.

The wood is excellent for construction and furniture. The species is protected by law and may only be harvested with special permission, but in recent years there has been several cases of trees being cut illegally.

Yellow cypresses, 600-700 years old, Mingchih National Forest. The lower picture shows a close-up of the bark, with a climber. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cunninghamia

A genus with one or two species, depending on authority. Some regard C. lanceolata, which is found in southern China, as a separate species, others consider it a subspecies of C. konishii (below).

Apparently, the generic name honours two persons, Scottish physician James Cunningham (died 1709), who introduced this genus into cultivation in 1702, and British botanist Allan Cunningham (1791-1839), who collected plants in Brazil and Australia. In 1839, he died of consumption in Sydney, only 47 years old.

Cunninghamia konishii Lunta spruce

A very large tree, growing to 50 m tall, with a trunk diameter up to 3.5 m, crown conical or pyramidal, dark green. Bark dark grey, dark brown, or reddish-brown, with deep fissures on older trees, which crack into flakes and thereby exposing the aromatic, yellowish or reddish inner bark. The needles are stiff, linear-lanceolate, arranged in dense spirals, glossy dark green above, to 6.5 cm long and 5 mm wide. Male cones are broadly obovoid, to about 2 cm long, sitting in groups of 8-20, female cones ovoid, to 3 cm long and wide, scales spreading at maturity.

In the wild, its occurrence is restricted to Taiwan, the Fujian Province in south-eastern China, and a few locations in northern Laos and Vietnam. According to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (2017), it is endangered in the wild.

The specific name is a Japanese surname, but I have not been able to find out who is being honoured. The English name refers to a mountain in Taiwan, Luan Ta, where this species was first found in 1908.

This huge Lunta spruce in Taroko National Park, Taiwan, called ‘Pilu Sacred Tree’, is about 3,200 years old, 50 m high, and has a trunk diameter of about 3.5 m. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lichens grow on the furrowed bark of this Lunta spruce in Malabang National Forest, Hsinshu, northern Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cupressus Cypress

About 15 species of these grand trees are distributed from the Mediterranean eastwards across the Middle East and the Himalaya to southern China and northern Indochina. Previously, a number of North American trees were included in this genus, but have now been transferred to the genus Hesperocyparis (below).

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kyparissos, the classical word for the Mediterranean cypress (C. sempervirens).

Cupressus torulosa Himalayan cypress

This magnificent tree may grow to 45 m tall, with a diameter up to 3.5 m, with spreading branches and drooping branchlets. The leaves are scale-like, triangular, to 1.8 mm long, with white margins, densely overlapping. The bark often peels off in large strips. When young, the cones are bluish, globular, to 2 cm long and 1.8 cm wide, grey when older, scales separating, when the fruit dries out.

It is distributed from Kashmir eastwards through the Himalaya to south-eastern Tibet, growing in dry areas, mostly on calcareous soil, at altitudes between 1,800 and 3,300 m. Its foliage is often burned as incense in Hindu and Buddhist shrines.

The specific name is derived from the Latin torulus, diminutive of torus (‘swelling’), presumably alluding to the furrowed bark.

Two magnificent specimens of Himalayan cypress, Upper Kali Gandaki Valley, Mustang, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hesperocyparis Western cypresses

These trees, comprising about 16 species, were formerly placed in the genus Cupressus (above). They are distributed from extreme western and southern United States southwards to Costa Rica. Most of the species have a very restricted range, and only a few are widely distributed.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek hesperos (‘western’) and kyparissos, the classical word for cypress.

Hesperocyparis macrocarpa Monterey cypress

This tree, previously known as Cupressus macrocarpa, is native to central California, formerly growing only on two small locations, Point Lobos State Park and Pebble Beach, both in Monterey County, south of San Francisco. Today, however, it has been planted in many other areas along the Pacific Coast, and also in Europe, New Zealand, South Africa, and elsewhere.

Due to the strong winds that blow in its native area, this species often becomes stunted, with an irregular trunk and a flat-topped crown. In sheltered places, it may grow up to 40 m tall, with a trunk diameter up to 2.5 m. The foliage is bright green, smelling of lemons when crushed. The leaves on older trees are scale-like, to 5 mm long, whereas young trees up to one year old have needle-like leaves, to 8 mm long. Male cones are very small, to 5 mm long, whereas female cones are globular or oblong, to 4 cm long, with 6-14 scales.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek makros (‘long’) and karpos (‘fruit’).

Both of these ancient Monterey cypresses were encountered in Point Lobos State Park. In the lower picture, the trunk is covered in an orange alga, Trentepohlia aurea. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hesperocyparis pygmaea Mendocino cypress

This tree, formerly known as Cupressus pygmaea, is restricted to a very small area around Mendocino, north of San Francisco, California. Its foliage is dull green, with scale-like leaves, to 1.5 mm long, in trees more than one year old, whereas seedlings have needle-like leaves, to 1 cm long. The cones are small, to 2.5 cm long.

The status of this species is disputed. Some authorities, including Kew Gardens, regard it as a separate species. Others maintain that it is a mere variety of the more widespread Gowen cypress (H. goveniana).

Under all circumstances, not much is pygmy-like about this tree, as it may be able to grow to a height of 43 m, with a diameter exceeding 2 m. The specific name may refer to the small cones.

The trunk of an old Mendocino cypress, illuminated by the evening sun, Laguna Point, Mackerricher State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Juniperus Juniper

This genus of c. 60 species of trees and shrubs is distributed in almost the entire Northern Hemisphere. The cone is berry-like, with an outer fleshy, leathery layer. Foliage of junipers is often burned as incense at Buddhist and Hindu shrines.

There are various theories as to the origin of the generic name. Some authorities claim that it stems from the Latin iungere (’tie together’ or ’weave’), referring to the use of its branches in baskets and fences, whereas others maintain that it is derived from juvenis (’young’) and parere (’to produce’), referring to the fact that juniper bushes constantly are renewed by new shoots.

The words gin and genever are derived from Juniperus, attesting to the usage of juniper fruits in these beverages.

Juniperus communis Common juniper

This is the most widespread conifer in the world, found in almost the entire northern subarctic and temperate zones, southwards to North Africa, northern Iran, the Himalaya, Japan, and Arizona.

It may grow to a large shrub, but is often prostrate, and may at once be identified by it needle-like leaves, to 1.3 cm long, which have a sharp point. The cone, to 8 mm across, is bluish-black when ripe, often with a bloom.

Common juniper is much utilized in folk medicine, and also plays a substantial role in folklore, described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘common’.

This old juniper in central Jutland, Denmark, has toppled, and the trunk is covered in mosses, but it is still full of life and growing vigorously. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Juniperus indica Black juniper

This high-altitude species is often a shrub, but at lower altitudes it may grow into a tree, up to 20 m tall. It has two kinds of leaves: on younger individuals, and sometimes also on lower branches of older specimens, the leaves are awl-shaped, to 6 mm long, whereas those on older branches are scale-like, to 1.5 mm long, densely overlapping in four ranks, which gives the branch a smooth appearance. The cone is brown when young, later shining blue or black, to 1.3 cm across.

This species is found at altitudes between 2,100 and 5,200 m, from Pakistan eastwards through the Himalaya to south-western China. Its foliage is burned as incense in Hindu and Buddhist shrines, and the fruit is utilized in traditional medicine for fever and headache.

This old and gnarled black juniper was photographed at an altitude of c. 3,600 m, Marsyangdi Valley, Annapurna, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

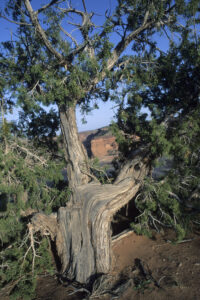

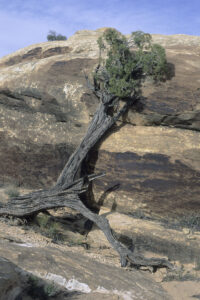

Juniperus osteosperma Utah juniper

A shrub or a small tree, growing to 6 m, rarely 9 m tall. It is native to western United States, from southern Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming southwards to eastern California, Arizona, and western New Mexico. It grows in dry areas, at elevations between 1,300 and 2,600 m. Its cones are berry-like, to 1.3 cm across, bluish-brown, with a whitish waxy bloom.

In former days, Native Americans used the bark for a variety of purposes, including beds, and ate the cones both fresh and in cakes. The gum was smeared on wounds as a protective covering. Tea made from the leaves was given to women to calm their contractions after giving birth. The Navajo would sweep their tracks with boughs from the tree, so that death would not follow them.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek osteon (‘bone’) and sperma (‘seed’), alluding to the hard seeds of this species.

Old Utah junipers often have strongly distorted trunks. These were observed in Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Arizona (top), and Inyo National Forest, White Mountains, California. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This stunted Utah juniper in Canyonlands National Park, Utah, has only a 10 cm wide strip of bark on the left side. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Juniperus pseudosabina Turkestan juniper

This shrub or small tree may reach a height of 10 m. It is native to mountains of Central Asia, found in south-central Siberia, Xinjiang, western Mongolia, eastern Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, north-eastern Afghanistan, and northern Pakistan, growing at altitudes between 2,000 and 4000 m.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek pseudes (‘false’) and sabina, the specific name of the savine (Juniperus sabina). Thus, the name means ‘the false savine’, presumably due to its similarity to the savine.

Lene Smith, standing at two ancient Turkestan junipers, growing over rocks, Yrdyk Valley, Kyrgyzstan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Juniperus recurva Drooping juniper

This species may grow into a tree, up to 20 m tall, but at higher altitudes it becomes a low shrub, often covering large areas. The bark is grey-brown, peeling off in thin strips. The growth is rather lax, and outer branches are often drooping and slightly recurved, hence the specific and common names. Leaves are awl-shaped, to 8 mm long, in whorls of 3, more or less adpressed to the branch and loosely overlapping. The cone is brown when young, later black, shining, ovoid, to 1.3 cm long.

It is distributed from Pakistan eastwards across the Himalaya and southern Tibet to Myanmar and the Yunnan Province, at elevations between 1,800 and 4,600 m.

Wood and foliage are burned as incense at Buddhist shrines.

Strictly speaking, the specific name means ‘bent backwards’ in the Latin. However, in this connection it means ‘bent downwards’, alluding to the pendulous branches.

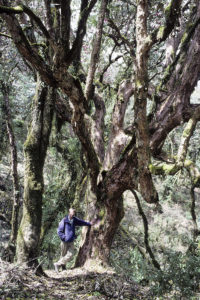

A growth of magnificent old drooping junipers near the Pangboche Monastery, Khumbu, eastern Nepal. These trees are sacred to the local Tibetan Buddhists – a remnant of the animist Bon religion, in which trees, prominent rocks, etc. were worshipped. This belief dominated in Central Asia prior to the introduction of Buddhism. This subject is described at length on the page Religion: Animism. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Juniperus virginiana Eastern redcedar, eastern juniper

This juniper is native to eastern North America, found from North Dakota and extreme south-eastern Canada southwards to Texas and Florida. It is a slow-growing conifer, usually below 20 m tall, with a trunk diameter up to 1 m, but on rare occasions up to 27 m tall with a diameter of 1.7 m. On poor soils it is low and stunted. The oldest specimen reported was about 940 years old.

Despite the name redcedar this tree is not related to true cedars of the genus Cedrus (see below).

Trunk of an old eastern redcedar, Parker River National Wildlife Refuge, Massachusetts. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Libocedrus

A small genus with 5 species of conifers, native to New Zealand and New Caledonia. The leaves are scale-like, to 7 mm long, in what looks like whorls of four. The cones are up to 2 cm long, with two pairs of rather thin, erect scales, each scale with a spine, to 7 mm long.

The etymology of the generic name is disputed. Some authorities maintain that it is derived from Ancient Greek libos (‘tear’) and kedros (‘cedar’), referring to the resin that oozes from the trunk. Others suggest that it is derived from the Greek libanos (‘incense’), and again kedros.

Libocedrus bidwillii New Zealand cedar

As its name implies, this species is restricted to New Zealand, where it grows in temperate rainforests at altitudes between 250 and 1,200 m. It is listed as near-threatened, and, apart from logging, the main threat is from browsing Australian brushtail possums (Trichosurus vulpecula), which may sometimes kill cedars. This introduced pest is presented on the page Nature: Invasive species.

It was named in honour of British botanist and explorer John Carne Bidwill (1815-1853), who investigated plant life in New Zealand and Australia, discovering several species new to science. In 1851, while marking out a new road in Queensland, Bidwill got lost and was without food for eight days. He eventually succeeded in cutting a way through the scrub with a pocket hook, but never properly recovered from starvation, and died in March 1853, 38 years old. (Source: Serle, P. 1949. Bidwill, John Carne (1815-1853). Dictionary of Australian Biography. Angus & Robertson)

Old New Zealand cedars, Tongariro National Park, New Zealand. Presumably, the lump on the trunk in the lower picture has been caused by fungi. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Metasequoia glyptostroboides Dawn redwood

This genus was described as fossils in 1939. However, in 1942 Chinese botanist Toh Gan discovered an unusual conifer in Lichuan County, Hubei Province. The locals called this tree 水杉 (‘water fir’). In 1942, specimens were collected, and, as it turned out, it belonged to the same genus as the described fossil tree of 1939.

This discovery caused a sensation in botanical circles around the world, and the species was called ‘a living fossil’. It is a large tree, growing to 50 m tall, and it is among the few conifers shedding its foliage in winter. Today, it is a popular ornamental in cooler areas around the globe.

The generic name is composed of Ancient Greek meta (‘near’), and the genus name Sequoia (Californian redwood, below), indicating that it is closely related to that species. The specific name is composed of the genus name Glyptostrobus (Chinese swamp cypress), and the Greek eides (‘like’), thus ‘resembling Chinese swamp cypress’.

An old dawn redwood, Maudslay State Park, Massachusetts. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bark of an old dawn redwood, eastern Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sequoia sempervirens Coast redwood

The tallest tree in the world, reaching a height of up to 115 m. It is also among the longest-living trees, some individuals being more than 1,800 years old. Before commercial logging began in the 1850s, this tree occurred in the wild along coastal California (excluding the southernmost parts), northwards to the south-western corner of Oregon. Today, it is restricted to rather scattered locations, from Monterey County, south of San Francisco, northwards to extreme south-western Oregon.

This species was originally named Taxodium sempervirens in 1824 by Scottish botanist David Don (1799-1841), but was moved to a new genus, Sequoia, in 1847 by Slovakian-born Austrian botanist, numismatist and sinologist Stephan Ladislaus Endlicher (1804-1849), also known as Endlicher István László, who was director of the Botanical Garden in Vienna. He never explained the reason for choosing this name. The specific name is derived from the Latin semper (‘always’) and virens (‘green’), thus ‘evergreen’.

Magnificent forest of coast redwood, Humboldt Redwood State Park, California. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lars Skipper (upper picture) and I seem like midgets, compared to the size and grandeur of these fallen, partly decayed trunks of coast redwood, Humboldt Redwoods State Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sequoiadendron giganteum Giant sequoia

In the wild, this relative of the coast redwood is found only in the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California. Specimens of this tree are the heaviest living beings on the planet, the largest ones having an estimated weight of c. 2,100 tons.

The following quote of Scottish-American writer and environmentalist John Muir (1838-1914), from 1870, is cited in the book John Muir: His Life and Letters and Other Writings, edited by T. Gifford, Mountaineers Books, 1996: “Do behold the King in his glory, King Sequoia! Behold! Behold! seems all I can say. Some time ago I left all for Sequoia and have been and am at his feet, fasting and praying for light, for is he not the greatest light in the woods, in the world? Where are such columns of sunshine, tangible, accessible, terrestrialized?”

Most people of that period did not share Muir’s enthusiasm. Despite the fact that their wood is fibrous and brittle, and of little use for construction, thousands of these magnificent trees were ruthlessly cut down, between the 1880s and 1924, even though their commercial value was marginal. The heavy trees would often shatter when they hit the ground, and it has been estimated that as little as 50% of the timber came to use. The wood was utilized mainly for shingles and fence posts, or even for matchsticks. – Imagine! From grand tree to matchstick!

Today, fortunately, felling of this species is strictly forbidden, and a few magnificent groves have been saved.

The generic name is composed of the genus name Sequoia (Californian redwood, above), and Ancient Greek dendron (‘tree’).

Other pictures, depicting these impressive trees, may be seen on the page Plants: Plants of Sierra Nevada.

Giant sequoias, Giant Sequoia National Park, Sierra Nevada Mountains, California. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Standing next to a giant sequoia, people appear like midgets. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Due to their thick, spongy bark, giant sequoias can withstand forest fires. However, there are limits to this resistance. In these pictures, two of the trees have succumbed. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In the 1930s, this giant sequoia was dubbed ‘Auto Log’, because its trunk was levelled, making it possible for cars to drive on it. This picture shows the root net of this tree. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

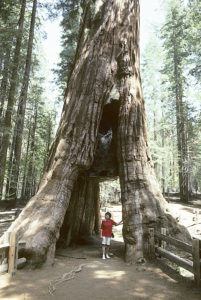

Likewise in the 1930s, a road was cut through the trunk of this giant sequoia in Mariposa Grove, Yosemite National Park. Today, fortunately, this type of vandalism is strictly prohibited. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Thuja Thuja, white-cedar, red-cedar, arborvitae

This genus contains 5 species, 3 in eastern Asia (China, Korea, and Japan), and 2 in North America. They are evergreen trees with reddish-brown bark, the largest growing to 70 m tall. The shoots are flat, leaves scale-like, to 1 cm long, but seedlings in their first year have needle-like leaves.

The generic name is derived from thuia, the Ancient Greek name of the stinking juniper (Juniperus foetidissima), originally from thuo (‘I sacrifice’), relating to the fact that wood of this species was often burned with animal sacrifices by the ancients to add a pleasing aroma to the fire. Why Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) applied the name to this genus is not clear. Maybe he found that the foliage resembled that of the stinking juniper.

Despite the names red-cedar and white-cedar, these trees are not related to the true cedars (Cedrus) of the Old World. The name arborvitae is Latin, meaning ‘tree of life’, stemming from the medicinal properties of these trees.

Thuja occidentalis Northern white-cedar, eastern arborvitae

A medium-sized tree, normally growing to a height of about 15 m, with a trunk diameter of up to 1 m. However, trees up to 38 m tall with a trunk diameter of 1.8 m have been observed. It is often stunted or prostrate in less favourable locations. The bark is reddish-brown and furrowed, peeling off in narrow, longitudinal strips.

It is distributed in south-eastern Canada and north-eastern United States, with scattered occurrence along the Appalachians southwards to Tennessee and North Carolina. It is widely cultivated elsewhere as an ornamental plant.

Trunks of old northern white-cedars, Lake Champlain, New York (top), and Parker River Wildlife Refuge, Massachusetts. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Thuja plicata Western red-cedar, giant arborvitae

A massive tree, sometimes growing to 70 m tall, with a trunk diameter up to 7 m, mainly growing in areas with a mild climate and high rainfall, in valleys and along streams. It may grow very old, some individuals being more than 1,000 years old.

It is native along the Pacific coast in south-western Canada and north-western United States, but is widely cultivated elsewhere as an ornamental, especially in northern Europe and New Zealand.

Previously, indigenous peoples used the wood of this species for canoes, totem poles, tools, and other items. Fibers from the bark was used to produce rope, baskets, clothing, and rain hats. Today, because of its aroma and resistance to rot, the wood is used for construction of shingles and siding.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘folded’, presumably alluding to the fan-like foliage.

This huge western red-cedar with multiple trunks grows in a park on the island of Lolland, Denmark. Lotte Møller Pedersen, who is peeping out behind one of the trunks, gives an impression of its size. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dipterocarpaceae

Dipterocarpus

About 70 species of large trees, to about 55 m tall, occurring from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to south-western China, and thence southwards through Indochina and Malaysia to Indonesia and the Philippines.

Many species are utilized for timber, and some were formerly used in traditional herbal medicine.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek di (‘two’), pteron (‘wing’), and karpos (‘fruit’), alluding to the two-winged fruit (see picture below).

Dipterocarpus alatus

A large evergreen tree, to 40 m tall, occasionally even to 55 m, with a straight, cylindric bole up to 1.5 m in diameter, often branchless up to 20 m, and with an umbrella-like crown. It is distributed in Bangladesh, north-eastern India, Indochina, and the Philippines.

This species is one of the most important timber trees of Indochina and is extensively logged commercially. It is threatened by habitat loss, listed as endangered in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. It is also much exploited for its resin, which is used in traditional medicine, as wood lacquering, and to make boats waterproof. Mixed with beeswax, it is used in bandages for ulcerated wounds. The bark of young trees is taken against rheumatism and liver problems, and is also given to cattle to stimulate appetite.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘winged’, alluding to the fruit.

Trunk of Dipterocarpus alatus, Bayon, Angkor Thom, Cambodia. In the background stone lions, carved during the time of the Khmer Empire (see page Religion: Hinduism). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fallen fruits of Dipterocarpus alatus, showing the two wings, Angkor Wat, Cambodia. These wings gave name to the genus and the entire family. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ericaceae Heath family

Rhododendron

A huge, almost worldwide genus with c. 1,025 species of evergreen trees, shrubs, shrublets, or climbers, with the largest concentrations in China, the Himalaya, Malaysia, Borneo, and New Guinea. China is the absolute stronghold of the genus, with no less than c. 571 species, of which 409 are endemic. The Himalaya is home to more than 100 species, and a tiny country like Bhutan harbours more than 60.

In Ancient Greek, rhododendron means ‘rose tree’, and, from a distance, the flower clusters of certain species may resemble roses.

A large collection of pictures, depicting rhododendron species from around the world, is shown on the page Plants: Rhododendron.

Rhododendron arboreum

This is one of the largest species of the genus, growing to about 15 m tall. The bark is reddish or brown. Leaves are oblong or lanceolate, to 20 cm long and 4.5 cm wide, glossy green above, the underside covered in a dense felt of whitish, fawn-, cinnamon-, or rusty-coloured hairs, veins on upper surface grooved. Flowers bright red, pink, or white, in clusters of 10-20, corolla bell-shaped, to 5 cm long and across, with 5 lobes to 1.7 cm long.

It is very common in the Himalaya, and in March-April, when the flowering is at its peak, it adds a reddish or pinkish tinge to the forest in numerous places, stemming from millions of flowers. The intensity of the red colour decreases with altitude, and white flowers may be observed near the upper limit of its distribution.

In Nepal, this tree is the national plant, called lali guras (‘red rhododendron’), and the flowers are brought as offerings in Hindu and Buddhist shrines. The petals are edible, utilized for sore throat and cough, and also pickled. Juice of the bark is taken for diarrhoea, dysentery, and cough, a paste of the leaves for headache, juice of the flowers for menstrual problems and dysentery. Juice of the leaves is spread on beds to get rid of vermin, and young leaves are used to stupefy fish in streams. The wood is utilized for making furniture, fences, and charcoal, and as fuel, and dried leaves serve as compost.

It is widely distributed, from Pakistan eastwards to montane areas of northern Thailand and Vietnam, with an isolated subspecies, nilagiricum, in mountains of South India, called Nilgiri rhododendron, and zeylanicum in Sri Lanka. These subspecies are regarded as separate species by some authorities.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘tree-like’, referring to its large size.

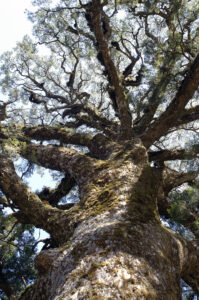

A magnificent old Rhododendron arboreum, Tadapani, Annapurna, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fabaceae Pea family

Acacia

These small to medium-sized trees are characterized by flowers with very small petals and numerous stamens. Formerly, the genus contained no less than c. 1,500 species, but according to the latest update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group’s classification for flowering plants, it is polyphyletic, today being divided into 5 genera, leaving about 980 species in Acacia, mainly restricted to Australasia. The remaining species have been transferred to the genera Vachellia, Senegalia, Acaciella, and Mariosousa.

The generic name is a Latinized version of Ancient Greek akakia, from akis (‘thorn’), referring to the prominent thorns of the Egyptian acacia (Vachellia nilotica), the first acacia species to be described scientifically.

A number of acacia species are presented on the page In praise of the colour yellow.

Acacia confusa Philippine acacia, Taiwan acacia, Formosan koa

This medium-sized tree, growing to a height of about 15 m, is native from south-eastern China and Taiwan southwards to the Philippines and Indonesia, but has been planted extensively elsewhere, including on many Pacific islands. In Hawaii, it is considered invasive. In Taiwan, where it is very common from the lowlands up to an altitude of c. 2,000 m, it is often protected, as it helps prevent landslides and soil erosion.

Philippine acacia has no true leaves, but phyllodes – winged leaf stalks, which function as leaves. They are scimitar-shaped, up to 11 cm long and 2 cm wide, with 3-5 parallel veins. The wood is very hard and was formerly used as beams in Taiwanese underground mines. Today, it is used to make floors, and to produce charcoal. The plant is also utilized in traditional folk medicine in Taiwan.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘mixed’ or ‘confusing’. What it refers to is not clear.

This gnarled Philippine acacia in Tunghai University Park, Taichung, Taiwan, has toppled, but is still growing vigorously. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Delonix

A genus with about 15 species of trees, 13 of which are endemic to Madagascar, with one species in Ethiopia, Somalia, and Kenya, and one in East Africa, and from southern Arabia eastwards to western India.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek delos (‘evident’) and onyx (‘claw’), referring to the central, upright petal, which is slightly curved, hereby resembling a claw.

Delonix regia Flamboyant tree, flame tree, royal poinciana

This tree, which grows to 20 m tall, has gorgeous flowers with 4 spreading, broadly spatulate, scarlet or orange-red petals, to 8 cm long, and a fifth, upright petal in the centre, called the standard, which is slightly larger, curved, and spotted with yellow and white. The flowers are arranged in terminal clusters. The pods are green when young, turning dark-brown and woody, as they mature. They may grow to 60 cm long and 5 cm wide.

The leaves are twice pinnate, bright green, growing to 50 cm long, with 20-40 pairs of primary leaflets, each divided into 10–20 pairs of secondary leaflets, not unlike huge feathers. When ageing, the tree may form large buttresses.

It is endemic to dry deciduous forests of Madagascar, but is cultivated as an ornamental in almost all warmer countries.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘royal’ – a suitable name!

Flamboyant trees are commonly planted in Taiwan. These pictures are from Tunghai University Park, Taichung. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The huge flat pods of the flamboyant tree can grow to 60 cm long and 5 cm wide. – Tunghai University Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tamarindus indica Tamarind tree

Despite its specific name, meaning ‘from India’, this evergreen tree, growing to 25 m tall, is native to Tropical Africa, but is widely cultivated elsewhere in hot countries. In 1753, when Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) named the plant, it had been cultivated for so long in India, that it was natural for him to think that it was indigenous there. It is the only member of the genus.

The pulp of the fruit is used in cuisines around the world, and in many Latin-speaking countries, a beverage called tamarindo is made from the pulp. It is also utilized in folk medicine, and the juice is used to polish metal.

The generic name is derived from Arabic tamar hindi, meaning ‘Indian date’.

Cyclist, passing by the gnarled trunk of an ancient tamarind tree, Bagan, Myanmar. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fagaceae Beech family

Castanea Chestnuts

This genus contains about 9 species, native to south-eastern Europe, the Near East, the Caucasus, Iran, China, Korea, Japan, and eastern North America.

The generic name is derived from kastana, the classical Greek name of the sweet chestnut (below).

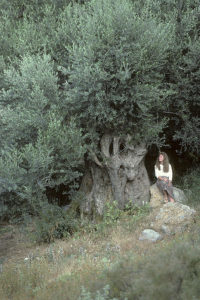

Castanea sativa Sweet chestnut

This large tree is native to the Mediterranean region, eastwards to the Alborz and Zagros mountains of Iran. It grows to 35 m tall and may live for 500 or 600 years. Cultivated specimens are reputedly 1,000 years old.