In praise of the colours violet, purple and lilac

Glass art with violet and blue streaks, Baltic Sea Glass, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Purple bands on eroded gullies, Badlands National Park, South Dakota, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Evening light adds a purple hue to the ice-covered Mill Neck Creek, Long Island, New York State. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flowering Persian lilac (Melia azedarach), Tunghai University Park, Taichung, Taiwan. The name refers to the flower colour. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Violet and purple are colours between red and blue in hue. Violet is generally used for hues close to blue, purple for redder hues. The term lilac indicates a pale violet tone. This page shows pictures, depicting all three colours.

The word violet stems from Old French violete, which refers to the flower colour of many species of violet (Viola), presumably originally sweet violet (V. odorata), which has been a popular garden plant for hundreds of years due to its fragrant flowers. This means that the term for the colour violet stems from the flower colour, not the other way around.

The genus Viola contains no less than 550-600 species, and members are found almost worldwide, with the highest diversity in temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere. The flowers have 5 very unequal petals, the lower one larger and spurred. The fruit is a capsule, splitting along 3 seams.

The flowers of most wild violets are various shade of blue or violet, but species with yellow and white flowers are also common (see page In praise of the colour yellow). Many species are popular garden plants, often called pansies, and this name is also used for 2 wild Eurasian species. It is a corruption of the French pensée, meaning ‘thought’ – these plants were regarded as a symbol of remembrance.

In the wild, sweet violet (Viola odorata) is found from central Europe and the Mediterranean eastwards to Kazakhstan and Iran, but is cultivated in temperate areas around the world. Its flower colour is usually bluish-violet, but a form with white flowers is also common.

Cultivated sweet violet, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The flowers of early dog-violet (Viola reichenbachiana) range in colour from blue to deep violet, and the long-stalked leaves are heart-shaped. It is a perennial, spreading mainly by means of runners, thus often forming large growths where undisturbed. It resembles the common dog-violet (below), but the spur is blue or violet, not white, and slightly slimmer than that of the common dog-violet.

This plant grows in broad-leaved forests, woodlands, and along roads. It is distributed in almost all of Europe, eastwards to the Baltic States and Ukraine, southwards to North Africa, Turkey, the Caucasus, and northern Iran.

The specific name was given in honour of Heinrich Gustav Reichenbach (1823-1889), a German specialist in tropical orchids. The prefix dog– is derogatory, indicating that these violets are scentless, and thus inferior to the sweet violet (above).

Early dog-violet, photographed on the island of Møn, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The common dog-violet (Viola riviniana) is quite similar to the early dog-violet (above), but can usually be identified by its whitish spur. However, the two species often hybridize, which complicates identification. The common dog-violet grows in similar habitats and has a similar distribution, but seems to be absent from Ukraine, Caucasus, and the Middle East. It also occurs in Iceland.

The specific name honours German physician and botanist August Bachmann (1652-1723), also known as Augustus Quirinus Rivinus, who improved classification of plants.

Common dog-violet, Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Common dog-violet, central Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The heath dog-violet (Viola canina) is distributed in all of Europe and further east to eastern Siberia, southwards to the Mediterranean and Kazakhstan. It is partial to acidic soil, growing in heaths and sand dunes. It may be identified by the fat, white spur. In this respect, it resembles common dog-violet, but lacks the leaf rosette of that species, and its leaves are normally narrower.

Like with other dog-violets, the name is derogative, reflected in the specific name, which is Latin, meaning ‘pertaining to a dog’.

Heath dog-violet, Fanø, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The spurred violet (Viola calcarata) is to 10 cm tall, stem smooth, with leaves on the lower part. Flowers are terminal, solitary, to 4 cm across, colour variable, blue, violet, yellow, or white, but always with a dark yellow spot near the throat, usually with violet veins. The lower petal has a spur, to 1.5 cm long, often pointing upwards.

This plant is found in the Alps, from France eastwards to Slovenia, and also on the Balkan Peninsula, southwards to Macedonia. It grows in grassy areas at altitudes between 1,500 and 2,800 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘having a spur’, alluding to the long spur of this species.

Spurred violet with raindrops, Cabane de Prarochet, Col du Sanetsch, Valais, Switzerland. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The arrowleaf violet (Viola sagittata) is found in a variety of habitats, including prairies, meadows, fields, river and lake shores, and woodlands, often in sandy or rocky soil. The leaves are all basal, much longer than wide, entire or lobed, often with a heart-shaped or square base. Petals are blue or purple.

It is widespread in eastern Canada and the United States, westwards to Minnesota, Oklahoma, and Texas.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘arrow-shaped’. However, in this connection it refers to the leaves, which resemble those of certain species of arrowhead (Sagittaria), which do not have arrow-shaped leaves.

Arrowleaf violet, Oswego Forest, Pine Barrens, New Jersey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Viola inconspicua is distributed from north-eastern India eastwards to Japan, and thence southwards through Indochina and the Philippines to Java. According to Kew Gardens, it also occurs in Mauritius, which is most odd, considering the great distance between the two distribution areas. Maybe they constitute 2 separate species.

By some authorities, the plants in Japan and Taiwan are regarded as a local subspecies, nagasakiensis, but this subspecies is not recognized by Kew Gardens.

Viola inconspicua is rather common at high altitudes in Taiwan, here observed on Hohuan Shan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The marsh blue violet (Viola cucullata) is distributed in eastern North America, from Newfoundland westwards to Ontario and North Dacota, southwards to Louisiana and Georgia. It is partial to wetlands, preferably growing in swamps.

The specific name is derived from the Latin cucullus (‘hood’) and the suffix atus (‘having a beard’), presumably alluding to the white tuft of hairs in the mouth of the flower.

Marsh blue violet, growing next to cinnamon ferns (Osmundastrum cinnamomeum), Shu Swamp, Long Island, New York. In the background leaves of eastern skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus). This species is presented on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wild pansy (Viola tricolor) is common almost everywhere in temperate areas of Eurasia. It is also found in North Africa, and has become naturalized in North America. It mainly grows on acidic or neutral soils in open areas, from sea level to elevations around 2,700 m.

The specific name alludes to the flowers having 3 colours: violet, yellow, and white.

These pictures show a variety of wild pansy, var. curtisii, called sand pansy, which is partial to sand dunes. – Fanø, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The vervain genus (Verbena), counting about 150 species of shrubby herbs, is native to temperate, subtropical, and tropical areas of the Americas, Europe, western and southern Asia, Africa, and Australia, with the majority in the Americas and Asia.

The tuberous vervain (Verbena rigida), also called slender vervain, is native to South America, from Bolivia and south-eastern Brazil southwards to northern Argentina. Elsewhere, it is a popular garden plant, which has become naturalized in numerous warmer areas around the world. The popular name alludes to its undergrond tuber.

Tuberous vervain, Jacksonville, North Carolina, United States. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bluewing, or wishbone flower (Torenia violacea), is a pretty plant of the family Linderniaceae. This species has a very wide distribution in warmer parts of Asia, from India eastwards to southern China and Taiwan, and thence southwards to Indonesia.

Bluewing is very common on the lower mountain slopes in Taiwan, where these pictures were taken. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Common sea-lavender (Limonium vulgare) is partial to salt marshes, where it often covers large areas – a spectacular sight late in the summer when it displays an abundance of lilac, purple, or pink flowers.

The leaves are all basal, oblong or spoon-shaped, to 15 cm long and 4 cm wide, dark green above, paler below. The flower stalk, which grows to 40 cm tall, is much-branched, each branch with a terminal inflorescence. The calyx is paper-like, surrounding the flower, which is to 7 mm long.

It is distributed from Scotland, Denmark, and southern Sweden southwards through western Europe to Portugal and Spain, and has also been reported from the Azores. According to some authorities, it also occurs in North Africa, and it has been introduced to North America.

The generic name was used by Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder (23-79 A.D.) for an unidentified plant, derived from Ancient Greek leimon (‘meadow’). The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘common’.

Common sea-lavender, Fanø, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The genus Anchusa, called alkanets, ox-tongue, or bugloss, belongs to the borage family (Boraginaceae). It contains about 38 species, native from Europe and North Africa eastwards to the Ural Mountains, Mongolia, and northern China, and also in Ethiopia and southern Africa.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek ankhousa, the name of Alkanna tinctoria, a plant of the same family, which was used as a cosmetic. The name bugloss stems from the Greek bouglosson, the name of Anchusa azurea, from bous (‘ox’) and glossa (‘tongue’), referring to the leaves, which are shaped like an ox-tongue and have a rough surface – just like the tongue of an ox.

The common alkanet (Anchusa officinalis), also known as common bugloss, probably originates from the Mediterranean area or western Asia, but was spread to the major part of Europe at a very early stage. Today, it ranges from Scandinavia and France eastwards to the Ural Mountains, Kazakhstan, and Turkey, and it has been introduced to North America, where it is regarded as a noxious weed in many places. It grows in disturbed habitats, often along roads, and in fallow fields and waste ground.

The small flowers are tubular, to 1.2 cm across, petals 5, fused, corolla initially reddish-brown, later changing colour to dark blue or purple. The plant was formerly cultivated for its edible leaves, and for the root, which was used as a dye and as a folk medicine. Originally, the name officinalis was derived from officina (‘workshop’, or ‘office’), and the suffix alis, which, together with a noun, forms an adjective, thus ‘made in a workshop’. However, in a botanical context, the word denotes plants species that were sold in pharmacies due to their medicinal properties.

Common alkanet, Djursland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Saffron is a spice made from the crimson styles of the flower of the saffron crocus (Crocus sativus). They contain a pigment, crocin, which adds a golden-yellow colour to textiles and dishes, especially rice. This dye has been used for thousands of years. There is much work involved in picking the styles off the flowers, and, at a price exceeding 5,000 US$ per kg, saffron is the world’s most expensive spice.

The native area of the plant is disputed, but Mesopotamia, Iran, and Greece have been suggested as possible places of origin. Cultivation of the saffron crocus slowly spread throughout much of Eurasia, and later the plant was brought to North Africa, North America, and Oceania.

The word saffron probably derives from Arabic zafaran, which stems from Persian zarparan, meaning ‘gold strung’, alluding to either the golden stamens of the flower, or to the golden dye extracted from the styles.

Cultivated saffron crocuses, Pampur, Kashmir, India. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Harvested saffron crocuses, Pampur. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Onion, leek, and garlic (Allium) is a huge genus with more than 1,000 species of herbs, distributed mainly in temperate and subtropical regions of the Northern Hemisphere, with some species in southern Africa. The core area of the genus is temperate areas of Asia. At one time, these plants were placed in the family Alliaceae, which is now regarded as a subfamily, Allioideae, of Amaryllidaceae.

The inflorescence is very distinctive, consisting of a compact globular umbel on an unbranched stem. Initially, the umbel is enclosed in a papery spathe, which splits into lobes, when the stalked flowers unfold.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of garlic (A. sativum), which is described in depth on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

In the wild, chives (Allium schoenoprasum) has a very wide distribution, found in all of Europe, the Middle East eastwards to the western Himalaya, and in all temperate areas of Asia, including Korea and Japan, and in Alaska, Canada, and northern parts of the United States. Elsewhere, it is widely cultivated as a vegetable and spice.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek skhoinos (‘rush’, genus Juncus) and prason ‘leek’, thus ‘rush-like leek’, naturally referring to the shape of the leaves.

Wild chives, Hallnäs Udde, Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wild chives, Col du Mt. Cenis, France. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cultivated chives, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Round-headed leek (Allium rotundum), also known as purple-flowered garlic, often divides, forming large growths, stem to 90 cm tall, leaves 2-5, flat and narrow, to 40 cm long. The rounded umbels may contain up to 200 bell-shaped flowers, to 7 mm across, petals purple, sometimes with white margin.

It is found from Germany and European Russia southwards to Morocco, Jordan, and Iran, growing in disturbed places, including fields, along roads, open slopes, and beaches.

Round-headed leek, Pointe du Toulinguet, Brittany. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

As opposed to most other Asian onion species, Allium wallichii thrives in humid areas, distributed from Pakistan eastwards to south-western China, at altitudes between 2,300 and 4,800 m. It is easily identified by its large umbel, to 7 cm across, with red or purple (rarely white) flowers. The flat, keeled leaves, to 2 cm broad, are edible, and the bulbs are used for diarrhoea, cough, and colds.

This plant was named in honour of Danish physician and botanist Nathaniel Wallich (1786-1854), who studied the Indian and Himalayan flora in the early 1800s.

Allium wallichii, just beginning to form fruits, Ghangyul (2500 m), Helambu, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tibetia himalaica, formerly known as Gueldenstaedtia himalaica, is a plant of the pea family (Fabaceae), which forms dense or lax mats of tiny, pinnate, densely silky-hairy leaves, to 7 cm long, with many leaflets of variable shape. The flowers are arranged in groups of 1-3, sometimes 4, on thread-like stalks, violet, blue, or deep mauve, sometimes red.

It grows at elevations between 3,000 and 5,000 m, from the Chinese provinces Gansu and Qinghai southwards across Tibet to Pakistan, and thence eastwards to south-western China.

Tibetia himalaica, Fanga, Gokyo Valley, Khumbu, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Blue jacaranda (Jacaranda mimosifolia) is native to north-western Argentina and southern Bolivia, growing on plains, flooded savannas, and montane slopes of the eastern Andes, up to an elevation of about 2,600 m. It is widely cultivated elsewhere in warmer countries due to its wonderful display of violet, fragrant flowers.

The name is of Tupi-Guarani origin, meaning ‘fragrant’. This name was adopted by the Portuguese.

Flowering blue jacaranda, Kathmandu, Nepal. The clock tower in the upper picture is Ghanta Ghar, originally built in 1894, but altered after the huge 1934 earthquake, when it was almost completely destroyed. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Scabious (Knautia) is a genus of about 48 species, native to Europe, North Africa, and Turkey, eastwards to central Siberia and Central Asia. The flowers are borne on inflorescences in the form of heads, similar to composites. Each head contains many florets.

Members of this genus are usually called scabious, although, strictly speaking, that name is reserved for a closely related genus, Scabiosa. Species of scabious were once utilized to treat scabies and other skin problems, hence the name. The word is derived from the Latin scabere (‘to scratch’).

The generic name was applied by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) in honour of two German brothers, Christoph Knaut (1638-1694) and Christian Knaut (1656-1716), both botanists and physicians. The latter published Compendium Botanicum sive Methodus Plantarum Genuina, in which he provided a classification system for flowering plants, based on petal number and arrangement.

Previously, these plants were placed in the scabious family (Dipsacaceae), but this family has been reduced to a subfamily, Dipsacoideae, within the honeysuckle family (Caprifoliaceae). The flowers are densely clustered in a terminal head, resembling composites of the family Asteraceae.

Field scabious (K. arvensis) is widely distributed, from western Europe eastwards across temperate areas of Asia to central Siberia, southwards to the Mediterranean, the Caucasus, Kazakhstan, and Mongolia.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘growing in fields’, derived from arvus (‘cultivated land’).

Field scabious, Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The main distribution area of the tall, bristly-hairy wood scabious (K. dipsacifolia) is the Alps and the Pyrenees, at elevations between 400 and 2,100 m. It also occurs in Hungary and the Balkans, and further north in scattered locations in Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Its habitat includes grassy areas, forest margins, and open forests.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with leaves like Dipsacus‘ (teasel).

Wood scabious, Rosanin Valley, near Thomatal, Austria. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The long-leaved scabious (K. longifolia) is much like the wood scabious (above), but the leaves are very long and narrow, long-pointed. It is distributed in the southern and eastern Alps, the Carpathians, and the Balkan Peninsula, growing in grasslands, shrubberies, and forest clearings, preferably on calcareous soils.

Long-leaved scabious, Passo Gardena, Dolomites, Italy. Kidney-vetch (Anthyllis vulneraria) and spiked yellow lousewort (Pedicularis elongata) are also seen. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Scales from a cone of Nordmann’s fir (Abies nordmanniana), gnawed by a red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris), Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Larkspur (Delphinium) is a huge genus with more than 500 species, found in most of the Northern Hemisphere, and also in eastern and south-eastern Africa.

Flowers are irregular, with 5 sepals, the upper one with a large, back-pointing spur, and 4 inner petals, of which the upper 2 have nectar-producing spurs that are enclosed in the larger spur.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek delphinion (‘dolphin’). In his De Materia Medica, Greek physician, pharmacologist, and botanist Pedanius Dioscorides (died 90 A.D.) says that the these plants are named for their dolphin-shaped flowers.

Rocket larkspur (Delphinium ajacis, also known as Consolida orientalis), is native to southern Europe, the Caucasus, Arabia, and from Turkey eastwards to Pakistan and Tibet. It is widely cultivated as an ornamental and has become naturalized in many other areas. In wild forms, the flowers are violet, but cultivated forms may also have pink or white flowers.

Rocket larkspur, growing in an abandoned field, together with corn poppy (Papaver rhoeas) and a species of Anthemis, near Aksaray, Turkey. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Barestem larkspur (Delphinium scaposum), also known as naked delphinium, is a tall plant, sometimes growing to 80 cm tall. It is distributed in desert areas of south-western United States and the Mexican state of Sonora, found on rocky hillsides, in juniper woodlands, and in grasslands, at elevations between 1,200 and 2,700 m.

The common names allude to the leaves being almost all basal.

Barestem larkspur, Saguaro East National Park, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The genus Erica, which has given name to the heather family (Ericaceae), is huge, containing more than 800 species, most of which are small shrubs, between 20 cm and 1.5 m tall, though some species are larger, the tallest being the tree heather (E. arborea) and besom heather (E. scoparia), both occasionally reaching a height of 7 m. The absolute stronghold of the genus is South Africa with around 690 species, most of which grow in a heath-like habitat, named fynbos. The remaining species are native to other parts of Africa, Madagascar, Arabia, Turkey, the Caucasus, and Europe west of Russia.

Cross-leaved heather (Erica tetralix) is native to western Europe, found from Scandinavia and Finland southwards to Portugal and Spain, westwards to the British Isles. It has also been introduced to eastern North America. It grows on acid soil in moorland, bogs, vegetated sand dunes, and along lakes.

It is a dwarf shrub, to 25 cm tall, with needle-like leaves, to 6 mm long, in whorls of 4, arranged crosswise. Leaves and sepals are covered in sticky glands. The rose-coloured flowers are in terminal racemes, corolla urn-shaped, pendent, to 9 mm long.

Like the common name, the specific name refers to the leaves, arranged in whorls of 4, derived from Ancient Greek tetra (‘four’).

Cross-leaved heather, Fanø, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bell heather (Erica cinerea) is likewise distributed in western Europe, from the British Isles eastwards to Germany, southwards to northen Spain and northern Italy. It is also found in southern Norway and on the Faroe Islands. It mainly grows on moors and heathland, but may also be found coastal dunes, and occasionally in woodland.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘ash-coloured’. What it refers to is not clear.

Bell heather, Pointe de Dinan, Brittany. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bell heather, Ross Wood, Loch Lomond (top), Loch Hourn (centre), and near Dervaig, Isle of Mull, Inner Hebrides, all in Scotland. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The red campion (Silene dioica), also known as red catchfly, is a beautiful member of the carnation family (Caryophyllaceae), formerly known as Melandrium rubrum. The colour of the flowers is a lovely reddish-purple.

This plant is distributed from northern Scandinavia and Ireland southwards to the Pyrenees, Italy, and the Balkans, and eastwards to western Russia. It has an isolated population in the Caucasus, and a scattered occurrence in Iceland, Spain, and western Siberia. It has also been introduced to North America. In northern Europe, it is very common, growing in shrubland, woods, along roads, and among rocks.

The generic name refers to the Greek woodland god Silenus, whose name is derived from the Greek sialon (‘saliva’). Silenus was often depicted covered in a sticky foam. The connection is that the female flowers of red campion secrete a frothy foam, which captures pollen from visiting insects.

The specific name dioica is the feminine gender of dioicus, from the Greek dis (‘twice’) and oikos (‘house’), thus ‘two houses’, referring to the fact that the plant has male and female flowers on separate plants. The former name Melandrium is derived from the Greek melas (’black’) and aner, genitive andros (’adult male’), referring to the dark (male) stamens, whereas rubrum is Latin, meaning ’red’.

On the Isle of Man, Britain, the plant is called blaa ny ferrishyn (‘fairy flower’) in the Gaelic, and traditionally there is a taboo against picking it. (Source: A.W. Moore 1924. A Vocabulary of the Anglo-Manx Dialect. Oxford University Press)

Red campion, growing together with common nettle (Urtica dioica), Nature Reserve Vorsø, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red campion is very common on the Danish island of Bornholm, where this picture was taken. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red campion, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Another member of the carnation family with the same flower colour is the sticky catchfly (Viscaria vulgaris), which is distributed from England eastwards to western Siberia, and from Scandinavia southwards to Italy, Greece, the Caucasus, and Kazakhstan. It has also become naturalized in north-eastern North America.

The generic name is Latin, meaning ‘resembling viscum‘ – the classical Latin name of mistletoe, from which a birdlime with the same name was produced. In this connection, the name refers to the sticky stem of this plant, on which small insects are often caught – reflected in the common name. The sticky substance may deter nectar thieves such as ants.

Fallow field with thousands of sticky catchfly, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sticky catchfly, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Beautyberries (Callicarpa) are a genus with about 160 species of shrubs, distributed from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to Korea and Japan, and thence southwards to Australia, and also in Madagascar, the southern United States, Central America, and northern South America.

These plants have dense clusters of purple flowers, which turn into purple or whitish, berry-like drupes. They were previously included in the vervain family (Verbenaceae), but have since been moved to the mint family (Lamiaceae).

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kalos (‘beautiful’) and karpos (‘fruit’), like the common name alluding to the colourful berries of some species.

An unidentified species of beautyberry, Nanren Lake, Kenting National Park, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

An unidentified species of beautyberry, Longdongwan Cape Trail, north-eastern Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fruit clusters of an unidentified species of beautyberry, Dasyueshan National Forest, central Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Persian silk tree (Albizia julibrissin) is a small tree in the subfamily Mimosoideae, of the huge pea family (Fabaceae). It is native to large parts of southern Asia, from the Middle East eastwards to China and Japan, but is widely cultivated elsewhere. Stamens of this species are white and reddish-purple, or entirely purplish.

The generic name was given in honour of an Italian nobleman, Filippo degli Albizzi, who introduced this species to Europe in the 18th Century. The specific name is a corruption of the Persian gul-i abrisham, from gul (‘flower’) and abrisham (‘silk’), thus ‘silk flower’.

Judy (lower picture) and her niece Guochin, showing stamens of Persian silk tree, Siao Liouchou Island, southern Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this picture from New Plymouth, New Zealand, masses of fallen stamens cover most of the ground. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Previously, purple owl’s clover (Castilleja exserta), also known as red owl’s clover, was placed in the genus Orthocarpus, named O. purpurascens. It is native to California, Arizona, New Mexico, and north-western Mexico. In former days, indigenous peoples of California harvested the seeds for food.

This species is crucial as a host plant for a threatened subspecies of the Bay checkerspot butterfly (Euphydryas editha ssp. bayensis), of the family Nymphalidae, which is endemic to the San Francisco Bay area.

Purple owl’s clover, Lake Saguaro, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Woolworth Tower in Manhattan, New York City, was built as early as 1913, and with a height of 241 m it was the tallest building in the world until 1930.

The night sky behind the Woolworth Tower assumes an almost violet colour. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rockroses (Cistus) is a genus of about 20 species of shrubs, growing on dry or rocky soils around the Mediterranean, from France, the Iberian Peninsula, and Morocco eastwards to the Caucasus and northern Iran, and also on the Canary Islands.

The generic name is derived from kistos, the Greek word for rockroses.

The gum rockrose (Cistus ladanifer) is well adapted to grow in the Mediterranean area, as it is able to withstand the hot summer due to a sticky substance that covers the entire plant. In Spanish it is known as jara pringosa (‘sticky rockrose’).

It is an invasive plant, which has taken over much of former farmland and grasslands in central Spain and much of southern Portugal.

The specific name refers to the fragrant resin of this plant, from which labdanum is extracted, used in herbal medicine and perfumes.

The flowers of gum rockrose are white with a dark purple spot at the base of each of the 5 petals, and bright yellow stamens. On this flower, the spots are unusually large. It was photographed in Parque Natural de Monfragüe, Extremadura, Spain. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Osbeckia is a genus of shrubs with spectacular violet, red, or pink flowers with a curved style and 8-10 yellow stamens in a dense cluster. The fruit is a capsule, opening by pores at the tip. The genus contains about 45 species, mainly found in tropical and subtropical parts of Asia, from India eastwards to Japan, and thence southwards to Australia, and also in tropical areas of West Africa, and on Madagascar.

The generic name honours Swedish explorer and naturalist Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805) who was an apostle of the famous Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778). In 1750-1752, he travelled on board the Prins Carl to Asia, where he spent four months studying flora, fauna, and culture of the Canton region of southern China. Returning home, he contributed more than 600 plant species to Linnaeus’ Species Plantarum, published in 1753. In 1757, he published an account of his work in China, called Dagbok öfwer en ostindisk Resa åren 1750, 1751, 1752. Med anmärkningar uti naturkunnigheten, främmande folkslags språk, seder, hushållning, m.m. (‘Diary of a Journey to the East Indies 1750, 1751, 1752. With notes about lore on nature, languages of foreign peoples, habits, household etc.’).

Osbeckia lanata is endemic to highlands of Sri Lanka. It may be identified by its small and crowded, ovate or rounded leaves with 3 deeply indented nerves. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘woolly’, referring to the underside of the leaves, which is covered in brown hairs.

Osbeckia lanata, Hakgala, Nuwara Eliya, Sri Lanka. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

An unidentified species of Osbeckia, Adam’s Peak Wilderness Sanctuary, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Petunia is a genus of about 20 species in the nightshade family (Solanaceae), native to South America. Hybrids (Petunia x atkinsiana or P. x hybrida) are very popular garden and house plants around the world.

The generic and popular names are derived from the French word pétun, which means ‘tobacco’ in a Tupi-Guarani language. Leaves and flowers somewhat resemble those of tobacco plants, which may be the cause of the mistake of the French.

Petunia as decoration in a city park, Brugge, Belgium. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

As its name implies, the beach vetchling or beach pea (Lathyrus japonicus, previously L. maritimus) is partial to beaches, growing in sandy or stony areas. It is native to arctic, subarctic, and temperate areas of Eurasia and North America, but with a disjunct occurrence, found in western and north-eastern North America, northern Europe, and from north-eastern Siberia southwards to Japan and south-eastern China. It has also become naturalized in Chile and Argentina.

Young pods and seeds are edible and were formerly consumed by various North American indigenous peoples. In his book Cape Cod (1865), American author Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) quotes that “in 1555, during a time of great scarcity, the people about Orford in Sussex, England, were preserved by eating the seeds of this plant, which grew there in great abundance on the sea-coast.”

However, the seeds contain a toxic amino-acid, which can cause lathyrism (muscle wasting), if consumed in large quantities. The leaves are used in Chinese traditional medicine.

Beach vetchling, Welwyn Preserve, Long Island, New York State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The native area of the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) is probably around the Mediterranean, but it has been cultivated for so long that this cannot be stated with certainty. It is grown to produce poppy seeds, which are used on bread and other foods, and for opium and other alkaloids, used in the medicinal industry.

It is an annual herb, growing to about 1 m tall, stem and leaves greyish-green, flowers to 10 cm across, with 4 purple, white, mauve, or red petals, sometimes with dark markings at the base. The fruit is a rounded capsule, topped with a cap, consisting of 12-18 radiating ‘ears’.

Cultivated opium poppies, Uluköy, northeast of Dinar, Turkey. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lantana is a genus of shrubs and herbs of the vervain family (Verbenaceae), counting about 115 species. These plants are distributed in most warmer areas of the globe, except Southeast Asia, New Guinea, and Australia.

In Late Latin, and in several dialects in Italy and Switzerland, lantana was the name of members of the genus Viburnum, and the name was also used in 1583 by Flemish physician and botanist Rembert Dodoens (1517-1585) for the Guelder rose (Viburnum opulus). Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) applied the name to the new genus, presumably because he found some similarities between the two genera.

Lantana involucrata is native to Mexico, the Caribbean, Central America, Columbia, and Venezuela, but is widely cultivated elsewhere as an ornamental. It grows to about 2 m tall, with downy, ovate, rounded leaves, which smell like sage (Salvia officinalis) when crushed. This gave rise to the common name buttonsage. The small, fragrant flowers are white, lavender, or lilac, arranged in terminal clusters. They turn into purple berry-like fruits.

Lantana involucrata, planted in a city park, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The prevailing religion in Taiwan is a unique blend of Buddhism and Daoism, described in depth on the page Religion: Daoism in Taiwan. During Daoist festivals, various rituals are performed, and lots of fireworks are ignited.

Colourful fireworks in front of a Daoist temple, dedicated to Wang-yieh, the god of diseases, Beimen, western Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Although the lion has never lived in Taiwan, it occurs abundantly as sculptures in Daoist temples, in the form of a mythological creature, which protects the temple. Such sculptures are also abundant on Daoist graves, guarding them against evil forces.

The lion also appears during the so-called lion dances, which are performed in front of the temples. As a rule, this dance is performed by two men, hidden under a gaily coloured cloth, which acts as the body of the lion, whereas a lion mask is held by the man in front.

During a Daoist procession, a lion dance is performed in front of a shop in the city of Taichung. Supposedly, this should cause the owner to make more money. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The genus Aster has given name to the composite family (Asteraceae). The word is Ancient Greek, meaning ‘star’, alluding to the spreading ray florets.

Alpine aster (Aster alpinus) is very variable, occurring in at least 10 subspecies. It has a huge distribution area, found in the major part of central and southern Europe, eastwards to Central and East Asia, and also in western North America. In Europe, an isolated population occurs in the Harz Mountains, northern Germany, probably an Ice Age relic.

Alpine aster, Passo Gardena, Dolomites, Italy. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Aster himalaicus is a small plant with spreading or erect stems to 25 cm tall, but often much lower. Flowerheads are terminal, solitary, to 4.5 cm across, with up to 50 lilac ray florets, whereas the disc florets are yellow, orange, or brownish-yellow. This species grows in open areas between 3,600 and 4,800 m altitude, from central Nepal eastwards to Myanmar and south-western China.

Early in the morning, the flowerhead of this Aster himalaicus, growing near the Kyanjin Gompa, Langtang National Park, central Nepal, was covered in rime, which by now has melted in the morning sun. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In former days, a large number of North American composites were included in the genus Aster (above). However, following comprehensive research, the New World species have been transferred to the genera Almutaster, Canadanthus, Doellingeria, Eucephalus, Eurybia, Ionactis, Oligoneuron, Oreostemma, Sericocarpus, and Symphyotrichum. Popularly, they are still called asters.

Despite its name, the New England aster (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae) is widely distributed, found in south-eastern Canada and the major part of the United States, except the south-western states. It is a robust plant, which may grow to 1.2 m tall. The flowerheads have numerous ray florets, sometimes up to 100, which are normally deep purple, occasionally pink or white. The likewise numerous disc florets are yellow or orange, turning brownish with age.

New England aster, Muttontown Preserve, Long Island, New York State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Golden dewdrop (Duranta erecta) is a small shrub of the vervain family (Verbenaceae), native from Mexico and the Caribbean southwards to Paraguay and Argentina. Elsewhere in warmer countries, it is widely cultivated as an ornamental and has become naturalized in many places. It is regarded as an invasive species in a number of countries, including Australia, China, and South Africa, and on several islands in the Pacific.

Other common names of this plant include pigeon berry and Brazilian skyflower, and in Tonga it is known as mavaetangi (‘tears of departure’), alluding to the fruit, which is a small, globose, yellow or orange berry, to 1 cm across. Unripe berries are toxic and are known to have killed children, dogs and cats. Birds, however, are not harmed by the berries. A picture, depicting the berries, is shown on the page In praise of the colour yellow.

The generic name was given in honour of Italian physician, botanist, and poet Gualdo Tadino (1529-1590), better known as Castore Durante da Gualdo.

Golden dewdrop is widely cultivated in Taiwan, in this case in Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Blueberry (Vaccinium myrtillus), a dwarf shrub of the heather family (Ericaceae), is described on the page In praise of the colour blue.

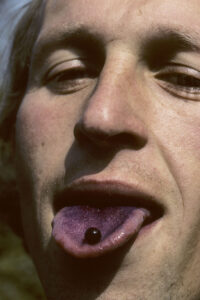

Blueberries are blue, but eating them gives a violet tongue. – Ib Krag Petersen, photographed on the island of Møn, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A close relative of blueberry is bog bilberry (Vaccinium uliginosum), which has a huge distribution, found in temperate and subarctic regions of the Northern Hemisphere, besides isolated populations in montane areas, including the Pyrenees, the Alps, and the Caucasus in Europe, the Sierra Nevada and the Rocky Mountains in North America, and mountains in Mongolia, China, Korea, and Japan. The berries have a slightly acidic taste. They are depicted on the page Autumn.

The specific name is derived from the Latin uligo (‘dampness’), referring to the fact that the prime habitat of this species is swampy areas.

This large growth of bog bilberry, growing in Nature Reserve Tipperne, Jutland, Denmark, displays a fantastic reddish-purple autumn foliage. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chinese tallow-tree (Triadica sebifera) is a smallish tree of the spurge family (Euphorbiaceae), native to China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan, and northern Vietnam. It was formerly called Sapium sebiferum.

The specific name means ‘wax-bearing’, referring to the tallow, which coats the seeds. Candles and soap are made from this wax, and in the Far East, the leaves are used in traditional medicine for treating boils. The sap and leaves are reputed to be toxic, and decaying leaves from the plant are toxic to other plants, inhibiting their growth.

Because of the tallow, this tree was introduced into the United States in the 1700s, and in the 1900s, it was widely planted along the Gulf Coast by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, in an attempt to establish a soap-making industry. However, it soon spread beyond control and is today regarded as a serious pest in south-eastern U.S., which expels native plant species. It is also regarded as invasive in India and Australia, and in Taiwan, despite being indigenous here.

In winter, the leaves of Chinese tallow-tree turn various gorgeous shades of red, varying from orange to wine-red. A collection of pictures, depicting this foliage, is shown on the page Autumn.

Young leaves of Chinese tallow-tree are often purple. It is ubiquitous in Taiwan, where this picture was taken. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The pretty grape hyacinths (Muscari) constitute a large genus with about 80 species, found from central Europe eastwards to European Russia, southwards to northern Africa, and thence eastwards across Arabia and the Middle East to Kyrgyzstan and northern Pakistan. Some species have become naturalized elsewhere, including northern Europe and the United States.

Most of these plants have racemes of dense, urn-shaped, dark blue, pale blue, violet, or whitish flowers, which, when young, resemble bunches of tiny grapes, hence the English name. In fruit, the inflorescence usually becomes elongated and lax.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek moskhos (‘musk’), referring to the scent of some of the species. The name can be traced back to 1601, to Flemish physician and botanist Charles de l’Écluse (1526-1609), also called Carolus Clusius, who was among the first to study the flora of the Alps. The name was formally established in 1754 by British botanist Philip Miller (1691-1771).

Muscari bourgaei is endemic to western and southern Turkey, growing in mountain grasslands and on stony slopes, at elevations between 1,500 and 3,000 m. The specific name honours French naturalist Eugène Bourgeau (1813-1877), who collected plants in numerous places, including the Canary Islands, North Africa, Turkey, Rhodes, western Canada, and Mexico.

Muscari bourgaei, Uludağ Mountains, north-western Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The showy dewflower (Drosanthemum floribundum), of the ice plant family (Aizoaceae), is native to the Cape Province in South Africa, but has become naturalized in other places, including California, north-western Mexico, western Europe, Morocco, Australia, and New Zealand. It is a creeping succulent with pretty, violet, lavender, pink, or occasionally white flowers, to 2.5 cm across.

Showy dewflower, Sunset Bluffs, San Diego, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

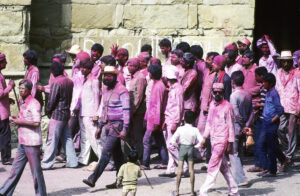

Holi is a Hindu spring festival, celebrating the god Krishna, and the victory of good over evil – a gay festival, in which people, regardless of caste, pelt each other with red, yellow, purple, or green powder, or with water, dyed with powder. For this reason, Holi has been dubbed The Festival of Colours.

My own ‘colourful’ adventures during Holi are related on the page Travel episodes – India 1991: Attending Hindu festivals in Rajasthan.

During Holi, these people in the city of Jaisalmer, Rajasthan, have had their share of purple dye. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cosmos is a genus with about 35 species of plants, belonging to the composite family (Asteraceae). They are native to southern North America, Central America, and northern South America, but many spacies are widely cultivated elsewhere for their beautiful flowers.

The garden cosmos (Cosmos bipinnatus) is native to Mexico, but as its common name implies, it is cultivated in many places.

Garden cosmos, cultivated in Wuling National Forest Recreation Area, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bougainvillea spectabilis is a woody climber of the four o’clock family (Nyctaginaceae), which may reach a height of 12 m. It is native to Brazil, Peru, Bolivia, and Argentina, but has been widely introduced elsewhere due to its gorgeous bracts, which are usually various shades of red, but may also be white, mauve, purplish, or orange. These bracts surround the small, white, inconspicuous flowers.

The name four o’clock family stems from another member of the family, the Marvel-of-Peru (Mirabilis jalapa), whose flowers do not open until late in the afternoon.

Bougainvillea spectabilis with reddish-purple bracts, Hanoi, Vietnam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Salsify, or goat’s-beard (Tragopogon) is a genus with more than 150 species, the vast majority found in drier areas of Central Asia and the Middle East. The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek tragos (‘goat’) and pogon (‘beard’). In some species, the involucral bracts contract before noon, closing the flowerhead, which has given rise to the popular name Jack-go-to-bed-by-noon. During this contraction, the seeds protrude from the flowerhead, hereby resembling a goat’s beard. The name salsify is a corruption of late 17th Century French salsifis, from obsolete Italian salsefica, which is of unknown origin.

The pretty Tragopogon coloratus is found in Turkey, the Caucasus, and Iran. It grows to about 60 cm tall, stem erect, branched or simple, smooth, densely leafy, leaves often longer than the stem, narrowly linear, pointed, margin wavy. Flowerheads solitary, to 4.5 cm long, involucral bracts 6-8, lanceolate, sharp-pointed, a little longer than outher florets, which may be purple, reddish-brown, pinkish, or violet. Anthers are bright yellow.

Tragopogon coloratus, Çukurbağ, Ala Dağları, Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Colchicum montanum, previously known as Merendera montana, has strap-shaped, linear leaves, to 22 cm long and 1 cm wide, which appear in spring, but wither during the summer. Late in the summer, the flowers appear, solitary, with 6 mauve or pinkish petals, to 6.5 cm long and 1 cm wide. The yellow anthers are large, longer than the filaments.

The whole plant contains the alkaloid colchicine, with the highest concentrations in the leaves, which deters herbivores from eating them.

It is widespread in the Iberian Peninsula, northwards to the Pyrenees, where it may be found up to an elevation of about 2,600 m. It is abundant in pasture lands, flourishing along roads and trails, often in dry and stony places. The highest density is found in highly disturbed areas with large populations of a species of vole, Microtus duodecimcostatus. Research suggests a symbiotic relationship between the two: the voles feed on the much less toxic rhizomes, which activates asexual reproduction processes. This mechanism is not observed in undisturbed pastures. (Source: D. Gómez et al. 2003. Seasonal and spatial variations of alkaloids in Merendera montana in relation to chemical defense and phenology. J. Chemical Ecol. 29 (5): 1117-1126)

Colchicum montanum, growing in bog moss, Alto Gallego, Pyrenees, Aragon, Spain. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Morning-glories (Ipomoea) constitute a huge genus with more than 500 species, widely distributed in tropical, subtropical, and temperate areas, especially in the Americas. Most species are twining plants with large, beautiful flowers, which unfold in the morning, then wither and fold up in the late afternoon, giving rise to the common name.

The generic name, from the Greek ip (‘worm’) and hómoia (‘resembling’), was applied by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) in allusion to the worm-like movements of the stem, which twines around other plants, fences, etc.

The railroad creeper (Ipomoea cairica), also known as coast morning-glory and mile-a-minute vine, is believed to be a native of Tropical Africa, but is today very widely distributed in tropical and subtropical areas around the world. It is capable of very rapid growth, sometimes completely entwining trees and bushes, but is also able to creep along the ground. It is regarded as an invasive species in many countries, including Australia, China, and Taiwan.

These pictures are from Taiwan, where railroad creeper is extremely common. The lower picture shows withering flowers. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Beach morning-glory (Ipomoea pes-caprae) is a very common plant on sandy beaches in all tropical and some subtropical areas of the world, easily spreading by its seeds, which are able to float for a long time, unaffected by salt water.

The specific name is derived from the Latin pes (‘foot’) and the Greek capra (‘goat’), referring to the shape of its leaves, which, to Carl Linnaeus, apparently resembled the footprint of a goat.

Beach morning-glory, Hambantota, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The native area of Uraria crinita, a member of the pea family (Fabaceae), is from north-eastern India, southern China, and Taiwan southwards through Indochina to Sumatra and Java, growing in drier areas, including grasslands, open forests, waste places, and along roads, from sea level to elevations around 1,500 m.

The stem is up to 2 m tall, and the inflorescence is a raceme, to 50 cm long, consisting of hundreds of whitish flowers with a bright violet or reddish standard (upper petal).

It is often gathered from the wild and used locally as a medicinal herb, and it is also cultivated as an ornamental, and as green manure.

Cultivated Uraria crinita, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The pokeweed family (Phytolaccaceae) is an almost worldwide family of herbs, shrubs, small trees, and climbers, comprising 5 genera and about 35 species. 4 genera are restricted to the neotropics, whereas Phytolacca is widespread. This genus, popularly known as pokeweed or inkberry, contains about 26 species of shrubby herbs, mainly distributed in tropical and subtropical regions of the Americas, South and East Asia, Turkey, sub-Saharan Africa, and Madagascar.

American pokeweed (P. americana, also known as P. decandra) grows to about 2.5 m tall, stem purplish, leaves alternate, long-stalked, lanceolate to ovate, entire, pointed, to 40 cm long and 10 cm broad. The flowers are arranged in dense, erect or pendent, long-stalked, cylindric clusters, to 30 cm long, always opposite a leaf, flowers white, pink, or greenish, to 5 mm across, sepals 5 (no petals). The fruit is a black or dark purple berry, to 1 cm across.

This plant is poisonous to humans, dogs, livestock, and other mammals. In spring and early summer, green parts are edible with proper cooking, but later in the summer they become deadly, and the berries are also poisonous. However, birds can eat them without ill effects, and they are an important source of food for birds like grey catbird (Dumetella carolinensis), mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos), cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis), brown thrasher (Toxostoma rufum) and others.

Pokeweed is native to eastern Canada, eastern and southern United States, and Mexico, but has become naturalized many other places around the globe. In some countries, it is regarded as a pest by farmers.

In Nepal, a close relative, P. acinosa, is cultivated, and tender parts are cooked as a vegetable. The root is used for constipation and wounds.

Berries and bright violet-purple fruit-stalks of American pokeweed, Planting Fields Arboretum, Long Island, New York. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In India, during certain Hindu festivals, it is a common practice to decorate the entrance to your home every morning with crayons. This picture is from Mysore, Karnataka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The bipinnate spikenard (Aralia bipinnata) is a shrub or small tree, to 7 m tall, trunk and branches covered in short prickles. The leaves are very large, sometimes more than 1 m long, twice pinnately divided, with a pair of leaflets at each division of the rachis, each with 7-11 ovate pinnae, to 7 cm long and 5 cm broad, tip pointed, base rounded, margins strongly toothed. The inflorescence is a large terminal panicle, up to 70 cm long, prickly, flowers white or yellowish, with small petals, about 2 mm long. The fruit is globular, purple, to 3 mm across.

The native range of this species is from southern Japan southwards through Taiwan and the Philippines to western New Guinea. It grows in open places and at forests edges, at elevations between 200 and 700 m.

Inflorescences of bipinnate spikenard with an abundance of small reddish purple fruits, Dasyueshan National Forest, central Taiwan (top), and with violet fruits, near Guoxing, western Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cranesbill (Geranium) is a large genus with about 380 species of herbs, mainly distributed in temperate areas, in the subtropics and tropics restricted to mountains.

The stipules (leaf-like appendices at the base of leaves) are often distinct on these plants. After flowering, the style forms a long, straight or up-curved beak, which separates into 5 elastic spring-like coils, each containing a single seed that is expelled, usually when the style is touched.

The generic name is derived from the Greek geranos (‘crane’), alluding to the fruit, whose shape resembles a crane’s bill.

Wood cranesbill (Geranium sylvaticum) grows in open forests and meadows, from the lowland up to elevations around 2,300 m. It is distributed in the entire Europe, from Iceland and the British Isles eastwards to central Siberia and Kazakhstan, southwards to Spain, Turkey, and northern Iran. It has also been encountered in southern Greenland, but may be introduced there.

The specific name means ‘growing in woods’, derived from the Latin silva (‘forest’).

Wood cranesbill, growing along a road, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wood cranesbill in rainy weather, Rossfeld, near Berchtesgaden, Bavaria, Germany. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Meadow cranesbill (Geranium pratense) possibly originated in Central Asia, but is today distributed from the entire Europe and Turkey eastwards almost to the Pacific Ocean, southwards to the Himalaya and northern China. It has also become naturalized in North America.

Meadow cranesbill, growing at the edge of a road, eastern Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sticky cranesbill (Geranium viscosissimum) is found in western North America, from southern British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan southwards to California and New Mexico. It grows in a variety of habitats, including pine forest, juniper woodland, meadows, and along rivers, at elevations between 1,000 and 2,500 m.

Stem, leaves, and flower stalks are covered with sticky hairs, and research has shown that the plant is able to absorb protein from insects that get stuck in these hairs.

Formerly, members of the Niitsitapi peoples (‘Blackfeet’) used an infusion from this plant to treat diarrhoea and other gastric problems, and also urinary trouble. The root was dried and powdered and then used to stop external bleeding. An infusion of the leaves was used to treat colds and sore throat.

Sticky cranesbill, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dusky cranesbill (Geranium phaeum) mostly grows in shady places, along forest edges and in shrubberies. It is native to southern, central, and eastern Europe, from Spain and France eastwards to the Balkan Peninsula and Ukraine, northwards to Poland and Belarus. It is widely cultivated and has become naturalized northwards to the British Isles, Sweden, and Finland.

Dusky cranesbill, Lake Gosau, Austria. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

When Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) named the bloody cranesbill Geranium sanguineum (Latin for ‘blood-red’), he did not refer to the flower colour, but to the fact that the leaves turn bright red in autumn. The flowers have a gorgeous reddish-purple colour. This plant is found from the British Isles eastwards to western Siberia, and from Scandinavia southwards to the Mediterranean and the Caucasus.

Bloody cranesbill, Samsø, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bloody cranesbill, growing among coastal rocks at Hammerknuden (top), and Randkløve, both on the island of Bornholm, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wearing a violet sari, this woman brings offerings of mallas (marigold garlands) to the sacred Ganges River, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ruellia tuberosa, of the family Acanthaceae, is native to Central America, but is widely cultivated elsewhere and has become naturalized several places, including eastern Africa, the Indian Subcontinent, and Southeast Asia.

Ruellia tuberosa, growing in a crack in a wall along a drainage canal, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Purple bush-bean (Macroptilium atropurpureum) is a climber of the pea family (Fabaceae), which is easily recognized by its deep purple flowers. It is indigenous to tropical and subtropical regions of America, from Texas southwards to Peru and Brazil. It has been introduced to many other countries as a fodder plant, but often escapes to form large growths which inhibit growth of indigenous species. It is regarded as invasive in Australia, South Africa, India, Hawaii, and many other islands in the Pacific.

Purple bush-bean has become widely naturalized in Taiwan, here photographed in abandoned plots in Taichung. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The genus Melampyrum, comprising about 40 species, are parasitic plants of the broomrape family (Orobanchaceae). They are distributed in arctic and temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere, southwards to Spain, Turkey, and China, and the Carolinas in America.

The generic name is derived from the Greek melampyron, of melas (‘black’) and pyros (‘wheat’), referring to the black seeds, which somewhat resemble wheat grains. An ancient belief had it that the seeds, when mixed with wheat and ground into flour, tended to make the bread black. In the Middle Ages, it was also believed that the seeds were capable of being converted into wheat, supposedly because of the sudden appearance of these plants among wheat, planted on recently cleared land. Cows and sheep readily eat these plants, hence the name cow-wheat. (Source: M. Grieve, 1931. A Modern Herbal. Jonathan Cape, here from botanical.com)

In his Cruydeboeck (herb book), Flemish physician and botanist Rembert Dodoens (1517-1585) tells us that “the seeds of this herb taken in meate or drinke troubleth the braynes, causing headache and drunkennesse.”

Wood cow-wheat (M. nemorosum) is distributed from Denmark and Sweden eastwards to western Siberia, southwards to the Mediterranean and Ukraine. It is quite common in eastern Europe.

Stem to 40 cm tall, branched, soft-haired, leaves opposite, short-stalked, lanceolate or ovate, upper ones toothed at the base. The lower flowers are in pairs from the leaf axils, upper ones in a one-sided, terminal spike, surrounded by crowded bracts, purplish-blue or violet, rarely yellowish-white, sepals fused, calyx bell-shaped, woolly-hairy, 4-lobed, corolla to 2 cm long, bright yellow, tubular, curved, 2-lipped, upper lip hooded, lower 3-lobed.

The specific name means ‘growing in woods’, originally derived from Ancient Greek nemos (‘a clearing in the forest’). Popular names include the Swedish natt-och-dag (‘night-and-day’) and the Russian Ivan-da-Marya (‘Ivan and Maria’), both names referring to its striking inflorescence with yellow flowers and bright purplish-blue or violet bracts.

Large growth of wood cow-wheat, Småland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wood cow-wheat, growing along a hedge near Halltorps Hage, Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wood cow-wheat, Laelatu Nature Reserve, Estonia. Note that the bracts are quite different from those of the Swedish plants above. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stachytarpheta, often called porterweeds, is a genus of about 125 species of shrubby herbs of the vervain family (Verbenaceae). Their flowers are much visited by bees, butterflies, and birds, especially smaller hummingbirds.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek stachys (‘spike’) and tarphys (‘thick’), referring to the inflorescence of many of the species in the genus.

Purple porterweed (Stachytarpheta frantzii), which grows to about 1.2 m tall, is native from Mexico eastwards to Panama.

A close relative, the blue porterweed (S. jamaicensis) is described on the page In praise of the colour blue.

Purple porterweed, El Castillo, Cordillera de Tilarán, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Blue Mesa is an area in Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona, which consists of thick layers of grey, blue, purple, or green mudstone, deposited about 220 million years ago.

This picture from Blue Mesa shows bands of purple layers, alternating with pale grey. In front a bit of a fossilized tree trunk. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cordyline fruticosa is an evergreen palm-like plant of the asparagus family (Asparagaceae), known by a number of common names, including ti plant, palm lily, cabbage palm, and good luck plant. This species grows to 4 m tall, having a fan-like cluster of leaves at the tip of the slender trunk. It is widely cultivated as an ornamental, and a large number of varieties with coloured leaves have been created, varying from reddish-violet to ruby-red to green, or a mixture of the three.

This plant, locally called ti, is of great importance to certain animistic religions of Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and many Pacific Islands. You may read more about this subject on the website en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cordyline_fruticosa.

Cordyline fruticosa as a house plant, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gorgeous reddish-violet leaves of Cordyline fruticosa, photographed in Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kudzu (Pueraria montana ssp. lobata), also called Japanese arrowroot, is a climber of the pea family (Fabaceae), which is native of eastern Asia, but has become naturalized in many other places. It grows vigorously, often completely enveloping indigenous vegetation and over time suffocating it. Today, it is regarded as a serious pest in several countries, including the United States and New Zealand. More about this issue is related on the page Nature: Invasive species.

Kudzu is much utilized in Chinese traditional medicine, described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

These pictures are from Taiwan, where kudzu is a native. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Most species of thyme (Thymus) are creeping dwarf shrubs with a strong fragrance. Leaves and flowers of some species are used as a spice. Some botanists recognize 300-400 species of these plants, which are distributed in subarctic, temperate, and subtropical areas of Eurasia, northern Africa, and Ethiopia. Others regard many of these species as subspecies of the widespread creeping thyme (below). Kew Gardens in London accepts about 267 species.

Creeping thyme (T. serpyllum) is native to northern and central Europe, and from England eastwards to western Siberia. It is a prostrate shrub with creeping stems, to 10 cm long, often forming dense mats, leaves evergreen, ovate, to 8 mm long, flowers in terminal clusters, corolla pink, lilac, or purplish, rarely magenta or white, to 6 mm long.

In the form herpyllos, the specific name was the classical Greek name of this plant, derived from herpo (‘to creep’). For some reason or other, this word became serpyllus in Latin.

Large growth of creeping thyme, Viborg, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Creeping thyme and a species of reindeer lichen (Cladonia), growing on an old dune, Fanø, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Close-up view of the flowers of creeping thyme, Fanø. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The genus Sunhangia, popularly known as tick-trefoil, contains 6 species, distributed from Afghanistan eastwards along the Himalaya to south-western China, and thence northwards to Gansu and Shanxi. They were previously included in the genus Desmodium.

The leaves are trifoliate, and the pods are flattened, conspicuously jointed between the seeds.

The trefoil part of the popular name means ‘three-leaved’, alluding to the 3 leaflets, whereas the tick part refers to the pods, which easily break apart into segments, each one containing a single seed with small hooked hairs that stick to people’s clothes or the fur of an animal, similar to the way a tick clings on with its legs.

Sunhangia elegans, previously known as Desmodium elegans, has the same distribution as the genus, found at altitudes between 1,000 and 4,000 m. It is a many-branched shrub, growing to 3 m tall. Leaves are trifoliate, long-stalked, young leaves reddish, leaflets variable, ovate, rhombic, or rounded, to 10 cm long and 7 cm broad. Flowers are in terminal clusters, to 30 cm long, flowers to 1.7 cm long, corolla lilac, dark purple, pink, or whitish, or a combination. The pod is linear, to 6 cm long and 6 mm broad, lower part of the margin indented between the seeds.

It is often cultivated as an ornamental. In Nepal, the root is used for cholera, and as a tonic, carminative, and diuretic, and the foliage is cut for fodder.

Sunhangia elegans, lower Langtang Valley, Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nightshade (Solanum) is one of the largest plant genera in the world, counting more than 1,300 species, including a number of very important food plants, such as potato (S. tuberosum), tomato (S. lycopersicum), tamarillo (S. betaceum), and eggplant (S. melongena).

The generic name is of unknown origin, possibly derived from the Latin sol (’sun’) referring to the fact that plants of this genus prefer to grow in sunny places. The popular name is a corruption of an ancient Germanic name of these plants, Nachtschatten, of unknown meaning. As Schatten also means ‘shadow’ in German, the name nightshade was introduced, but apparently this is a misnomer.

Solanum etuberosum is a spectacular plant, to 1.5 m tall, leaves pinnate, to 35 cm long and 15 cm wide, flowers violet, to 3.5 cm across, fruit globose, green or deep purple, to 1.3 cm in diameter. It is endemic to central Chile, growing in dry scrub forest or along streams on the slopes of the Andes, up to an altitude of about 2,500 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘without tubers’.

Solanum etuberosum, Reserva Nacional Altos de Lircay. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Purple nightshade (Solanum xanthi) is easily identified by its large, gorgeous flowers, which have green and white markings in the centre. It is native to south-western North America, in Arizona, California, and Baja California,

Purple nightshade, Torrey Pines State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The woolly nightshade (Solanum mauritianum), also known as velvet nightshade, is a shrub or small tree, usually 2-4 m tall, but may grow to 10 m under favourable conditions. The long-stalked, ovate or elliptic, entire leaves are large, to 40 cm long, and like the stem they are greyish-green, covered in whitish hairs. The inflorescence is a cluster of star-shaped purple flowers with a faint white streak radiating on each petal. The stamens are bright yellow, and the style is white. The fruit is a yellow berry, to 2 cm across.

Woolly nightshade is native to eastern South America, but has become naturalized in many other warmer areas of the world.

Woolly nightshade, near Wushe, central Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Another member of the nightshade family is the beautiful Schizanthus hookerii, also called butterfly flower, fringe flower, and poor man’s orchid. The flowers of this genus, which is native to Chile and Argentina, are pollinated by bees, bumblebees, and wasps.

Schizanthus hookerii, Reserva Nacional Altos de Lircay, Chile. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chervil (Chaerophyllum) is a genus of about 35 species, native to Europe, North Africa, Asia, and North America. The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek khairephyllon, from khairo (‘to be glad’ or ‘to please’), and phyllon (‘leaf’), thus ‘with pleasing foliage’. It was the classical name of garden chervil (Anthriscus cerefolium), a culinary herb, which is much used in Mediterrenean kitchens. Why the name was applied to this genus, is not clear. However, the leaves of some of the species do resemble those of garden chervil.

Rough chervil (C. temulum) is a pioneer plant, found in a variety of habitats, including forest edges, waste places, and along walls and fences. It is distributed in the major part of Europe, eastwards to the Ural Mountains, the Caucasus, and Turkey, and also in north-western Africa.

The purplish, very hairy stem grows to about 1 m tall, leaves long-stalked, twice or thrice pinnate, pale or dark green, lobes ovate in outline, deeply toothed. Flowers are white. The plant is poisonous.

The specific name is derived from the Latin temulentum (‘drunken’), derived from temetum (‘an intoxicating drink’) and ulentus (‘full of’), alluding to the symptoms from poisoning by the plant being similar to those of alcoholic intoxication.

After flowering, rough chervil often assumes a purple colour. This picture is from eastern Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Knapweed, or centaury, genus Centaurea, is a huge genus, counting maybe between 600 and 700 species, found in Eurasia and Africa, mainly in temperate and subtropical regions. Their core area is Turkey, which has at least 170 species, many of them endemics with a very restricted distribution.

These plants do not have ray florets, but are characterized by most species possessing two types of disc florets, the outer ones much larger, fringed, sterile, acting as attractors to pollinators.

The generic name is derived from the Greek kentauros (‘centaur’), referring to Chiron the Centaur. According to Greek mythology, Chiron once had a festering wound on his foot, made by an arrow dipped in blood of Hydra, a many-headed serpentine monster with a poisonous breath and blood so virulent that even its scent was deadly. Chiron cured himself by dressing the wound with a member of this genus.

These plants have many common names, including centaury, knapweed, starthistle, and cornflower, the latter usually referring to two blue-flowered species, C. montana and C. cyanus, described on the page In praise of the colour blue.

The greater knapweed (Centaurea scabiosa) thrives in drier grasslands, along roads, and in fallow fields, preferably on calcareous soils. It is distributed in almost all of Europe and thence eastwards across the major part of Siberia to Central Asia.

The stem grows to 1.2 m tall, grooved, hairy, branched above the middle, leaves alternate, stalked, to about 10 cm long, dark green, usually pinnately lobed, lobes narrow. Flowerheads usually purplish-red, sometimes pink, solitary at the end of stem and branches, to 4 cm across, involucral bracts ovate, dark-edged, with fuzzy bristles along the margin.

The specific name refers to an old belief that the leaves of this plant could treat scabies.

Greater knapweed, eastern Funen, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The black knapweed (Centaurea nigra) may grow to 1.5 m tall, stem erect or ascending, branched above, downy or scaly, lower leaves oblanceolate or elliptic, to 25 cm long, margin entire or shallowly toothed, or sometimes pinnately lobed, upper leaves sessile, linear or lanceolate, entire or toothed, getting gradually smaller up the stem. The involucral bracts are very dark, and the purple florets are arranged in a very compact head.

It is distributed in Europe, from the British Isles eastwards to Poland, southwards to Morocco and Croatia. It has become naturalized in Scandinavia, Australia, and North America, in some places regarded as invasive.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘black’, referring to the very dark involucre.

Black knapweed, Drymen, Loch Lomond, Scotland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Brown knapweed (Centaurea jacea) resembles black knapweed, but the involucral bracts are pale brown, not blackish, and the flowerheads are much less compact. It grows to about 80 cm tall, stem erect or ascending, branched above, leaves simple, alternate, somewhat hairy, lower ones often stalked, to 25 cm long and 2.5 cm wide, sometimes with a few lobes or teeth, upper ones smaller, lanceolate, entire, stalkless. Flowerheads are purplish or sometimes pink, to 3.5 cm across, single at the end of branches.

It is found in rather dry grasslands and open woodland, from almost the entire Europe eastwards to central Siberia, southwards to the Mediterranean and the Caucasus.

Brown knapweed, near Løgstør, northern Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Counting about 880 genera and more than 22,000 species, orchids comprise one of the world’s largest plant families, Orchidaceae, found almost worldwide. These plants are divided into terrestrial species, growing in soil, and epiphytic species, growing on trees (sometimes on rocks or fallen tree trunks). The latter develop aerial roots that absorb nutrients and moisture from the air, and many have pseudobulbs, swollen, fibrous, bulb-like stems that store water and nutrients.

The flower structure of this family is unique. There are 3 sepals, often coloured and shaped like 2 of the 3 petals. The third petal forms the lower lip, usually differing very much from the other petals in size and shape, and sometimes in colour, often with a spur. Stamens and ovary are fused, forming the so-called column. Anthers and stigma are separated by a beak-like structure, the rostellum. The anthers produce so-called pollinia, small ‘bags’ which contain pollen. These pollinia easily stick to visiting insects by a sticky secrete, and the insects then transport them to the next flower where they get attached to the stigma. Other species are self-pollinating. The fruit is a capsule, containing countless tiny seeds, spread by the wind.

Most of these plants live in symbiosis with the mycelium of underground fungi, which is attached to the rhizome or root of the plants. When an orchid seed is about to germinate, it is completely dependent on this mycelium, as it has virtually no energy reserve, obtaining the necessary carbon from the fungus. Some orchids are dependent on the mycelium their entire life, but their relationship is symbiotic, as the orchid delivers crucial water and salts to the fungus. However, some species do not contain chlorophyll, being parasites on the fungi.

Orchis is a genus with about 22 species, occurring from northern and western Europe eastwards to central Siberia and Mongolia, southwards to northern Africa, Iran, and Xinjiang.

The generic name is Ancient Greek, meaning ‘testicle’, referring to the shape of two rounded or ellipsoid, subterranean tubers of members of the genus.

The stem of the early purple orchid (Orchis mascula) is to 60 cm tall, green below and gradually turning purplish upwards, being very dark purple in the terminal inflorescence. It has 3-5 basal leaves, oblong, pointed, often with purple blotches, and on the lower half of the stem are several sheathing leaves. The terminal inflorescence is a more or less dense, cylindrical spike, to 12.5 cm long, consisting of 6-20 purple or pinkish-purple flowers.

It is found in the entire Europe, except Iceland, eastwards to European Russia, southwards to northern Africa, Iraq, and Iran, growing in woods, meadows and other grasslands, and in montane pastures up to elevations around 2,500 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘male’, referring to the two rounded or ellipsoid, subterranean tubers, which resemble testicles.

Early purple orchid, Hallnäs Udde, Öland, Sweden. Tall buttercup (Ranunculus acris), silverweed (Potentilla anserina), and a species of sedge (Carex) are also present. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The magnificent military orchid (Orchis militaris), also known as soldier orchid, grows to about 60 cm tall, with 2-6 bright green, oblong, pointed basal leaves, to 18 cm long and 5 cm wide, and a robust stem with smaller, sheathing, upright leaves. The terminal inflorescence is cylindrical, carrying up to 40 purplish flowers with a paler helmet-shaped hood, formed by the upper petals and sepals, hence the specific as well as the English name.

This species grows on alkaline soil in grasslands, shrubs, at forest edges, and along roads, distributed from England eastwards to central Siberia and Mongolia, southwards to the Mediterranean, Iran, and Xinjiang. In Sweden, it is restricted to the southern parts, being most common on the islands Öland and Gotland. In Finland and Denmark it is very rare.

Military orchid, Hallnäs Udde, Öland, Sweden. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)