Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Iran & Turkey 1973: “Kurdistan! Bum-bum-zip!”

In places, flowering crocuses, irises, and many others add bright colours to the otherwise drab steppe. The ground is dotted with numerous dens, inhabited by two species of ground squirrel. One is the fat bobak marmot (Marmota bobak), the size of a hare, the other the slim Anatolian ground squirrel (Spermophilus fulvus), not much larger than a rat. When they notice us, they emit a shrill, whistling call, withdrawing into their den.

Many birds have arrived from their wintering areas. In small puddles along the road, red-necked phalaropes (Phalaropus lobatus) swim around in circles, the whirling bringing water insects to the surface. Spotted crakes (Porzana porzana) scurry from one reedbed to the next, and collared pratincoles (Glareola pratincola) twitter above our heads. Beautiful rollers (Coracias garrulus) and red-footed falcons (Falco vespertinus) are perched on wires, keeping a lookout for dragonflies and other insects. On buildings and in trees, many nests of white storks (Ciconia ciconia) are already occupied.

In Ancient Palestine, a ‘clean beast’ was any animal that would chew the cud and have a completely split hoof, i.e. cattle, sheep, goats, and other members of the family Bovidae, whereas ‘unclean beats’ were other animals.

Three Kurdish sheep herders, accompanied by a couple of enormous, long-haired sheepdogs, approach our car to inspect the strangers. One is clad in a coarse felt cape, and they all carry thick herder’s sticks. Our conversation is rather limited, as we have almost forgotten the tiny bit of Turkish, that we learned in November. But, as usual, we get quite far using sign language. Huge herds of sheep are grazing in the meadows, and if some of them stray into the wheat fields, the herders whistle and shout to scare them out again. When the sheep ignore their calls, the men hurry out into the meadows, followed by their dogs.

After sunset, it quickly gets rather cold, and we retire early. However, we are not permitted to rest for long. Outside, a car comes to a stop, and men peep through our rear window, using torches. We get up to open the door, whereupon a police officer and three soldiers, armed with rifles, approach us.

“Kurdistan! Kurdistan! Bum-bum-zip!” says the police officer, using sign language to illustrate how Kurdish bandits will arrive during the night to shoot us and afterwards cut our throat. Despite the severity of the matter, it looks so funny that we cannot help laughing.

We do our best to persuade them to let us sleep here, as we have learned from other travellers that the Kurds don’t mind tourists – only Turks. But to no avail. They order us to follow their car to the nearest town, Dogubayazit, and sleep there. Turkish soldiers are very much afraid of the Kurds – not without reason, as many of their colleagues have been killed by Kurdish guerillas.

In former times, a small part of Kurds were sedentary farmers, but the majority were nomads, who, with their herds of sheep and goats, roamed the mountains of eastern Turkey, north-eastern Syria, northern Iraq, north-western Iran, and the adjacent parts of the Caucasus. Farmers and nomads would benefit from each other, as much trading took place between them. Cereals and vegetables were exchanged for mutton, felt, and wool. Today, however, almost all Kurds are sedentary.

This people has been a victim of political interests, as imperial powers have drawn borders all across their land. During World War I, the Kurds were fighting the Turks alongside the British, who in fact promised them that they would have an independent Kurdistan in eastern Turkey after the war. The treaty with the British was never ratified, and when, during the Turkish-Greek War in 1919-20, Mustafa Kemal (later called Atatürk – ‘Father of Turks’) and his generals turned out to be a considerable power, the British ‘forgot’ what they had promised the Kurds.

The Turks continued to rule the Kurds, and two uprisings in the 1920s were brutally crushed by Kemal’s soldiers. Many Kurds were imprisoned and later executed, and thousands of poor peasant families were forcefully moved to western Anatolia.

Kemal now introduced a new policy: Turkey was for Turks, and everybody who wanted to live in Turkey, had to speak Turkish. Even though many Kurds had participated in the Turkish-Greek War, they were brutally suppressed – the Turks even refused to acknowledge them as a separate people. They were called ‘Mountain Turks’, and the Kurdish language – based on a ‘scientific’ report from the 1920s – was regarded as a Turkish dialect, even though the two languages are not at all related. It was forbidden to teach in Kurdish in the schools. In Iraq, the Kurds were also suppressed and persecuted by the Arab rulers in Baghdad, as the two peoples had always been hostile towards each other.

In the 1970s, the Kurds numbered about 15 million people, of these 7 million in Turkey. The Turks still regard them as Turks, and Kurdish political parties are forbidden. Nevertheless, several exist. The Kurds have no other options than an armed conflict. Kurdish guerillas are considered terrorists by the government, and this is the reason why the soldiers fear for our lives.

Persecution of national minorities in Turkey was not introduced by Atatürk. From ancient times, all of north-eastern Anatolia was inhabited by Christian Armenians, who were farmers and traders. In the late 1800s, a large group of Armenians demanded an independent state, and on two occasions, in 1895-96 and 1914-15, Turkish troops (sometimes assisted by the Kurds!) attacked and killed thousands of Armenians.

This was genuine genocide, and it is estimated that about one million Armenians were killed. The majority of the survivors fled to Russia, where they later got their own Soviet Republic, Armyanskaya SSR. Many of the Armenians, who stayed in Turkey, later emigrated to Soviet Armenia, USA, and Europe.

The towns in this area are grey, bleak, and dirty, with roads of cobbled stones, filled with holes. Each and every town possesses an army camp, and guarding soldiers are ubiquitous. Near the town of Ağrı we are stopped by a soldier, standing beside a broken-down bus. He asks for a lift to town. When he spots our cassette tapes, he takes one of them and places it in his basket. I have to ask him to get it back.

“What a snotnose!” says Arne, when the man has left.

The fields along the road are covered in crocuses, lilies, and lesser celandines, and cranes (Grus grus) are feeding here, together with white storks, rooks (Corvus frugilegus), and lapwings (Vanellus vanellus). The weather is dark and rainy.

A fair number of tourists must be passing through this area, judging from the behaviour of the sheep herders. They run towards our car, demanding cigarettes, and when we refuse to give them any, some even throw stones at our van, another beating the car with his stave.

The bumpy tar road becomes a gravel road, and we start our ascent towards a pass, Tahir Geçidi, and yet another pass, Kopdağı Geçidi. The landscape around these passes is covered in a thick layer of snow. The inhabitants of the few dilapidated villages here are as unpleasant as the herders down on the plains. The houses are built of granite stones, with a flat roof, a few of them with a covered chimney.

In bare patches among the snow drifts, white and violet crocuses grow together with marsh marigolds (Caltha palustris). Horned larks (Eremophila alpestris), crimson-winged finches (Rhodopechys sanguineus), and snow finches (Montifringilla nivalis) hop about in the grass. North of the last pass, the road heads down through a wild gorge, surrounded by high crags, before entering the level plains again.

At a petrol station, we ask permission to park and sleep in our car. The attendant invites us into his spartan room, containing a table, three chairs, and an iron stove on the raw concrete floor. He disappears into the next room and returns with tea and sugar. As it is very cold outside, we stay near the stove until late in the evening.

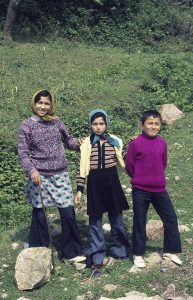

On our way towards the next pass, we make a stop to enjoy the gorgeous view. Suddenly, 4 school girls appear, seemingly jumping out of the sky. They have made a shortcut from one hairpin bend to the next, climbing down an almost perpendicular rock wall.

In the thickets, chaffinches (Fringilla coelebs) and blackbirds (Turdus merula) are singing, and among the grass grow primroses (Primula), snowbells (Soldanella), and a species of hellebore, called the Lenten rose (Helleborus orientalis), named for its early flowering. In Christianity, the Lent is a period of 40 days prior to Easter.

Back on the plains, we pass through numerous villages with narrow streets and houses with tiled roofs. There are groves of green trees, and hazel plantations, producing the nuts that we buy in European supermarkets at Christmas. The sky is dark, and rain is pouring.

We pass the coastal town of Trabzon, founded by the Greeks in the 7th Century B.C. For 250 years, between 1204 and 1461, this city was the capital of the Trapezunt Empire.

Along the road are dense thickets of tree heath (Erica arborea) and two species of rhododendron, the reddish-violet Rhododendron ponticum and the yellow R. luteum. (You may read more about these, and many other species of rhododendron, on the page Plants: Rhododendrons.)

In open areas, we find herbs like yellow saxifrage (Saxifraga), blue forget-me-not (Myosotis), and a red-flowered form of English primrose (Primula vulgaris ssp. sibthorpii). To our surprise, we observe a sub-adult male trumpeter finch (Bucanetes githaginea), quite far from its usual area of distribution, which is deserts near the Mediterranean.

Villages and towns are numerous along the coast. In Espiye, we shop at a local market, where all sorts of items are sold, including beautiful copper kitchenware. Obviously, Europeans are not a common sight here, and shortly after our arrival quite a few people follow us around. A barber approaches me, grabs my arm and leads me to his shop. I am convinced that he wants to cut my rather long hair, but he just wants to serve tea.

Accompanied by a local man, who speaks German, we stroll in the neighbourhood. Many of the houses are very attractive, built entirely of wood. Several women are working in a field, turning over the soil and cutting the weeds into tiny bits. They are astonished to see us, but invite us to join them, offering us refreshing buttermilk. Ten steppe buzzards (Buteo buteo ssp. vulpinus) and one honey buzzard (Pernis apivorus) are soaring over a nearby hill.

At dusk, we stop for the night at a brook, in which little bitterns (Ixobrychus minutus) walk about. A tawny owl (Strix aluco) hoots, and an evening chorus of howling golden jackals (Canis aureus) is heard from far away.

In the evening, we are paid a visit by two peasant girls, dressed in the local red women’s dress. They are spectacular, but when I try to take pictures, they run away, giggling. The kids assist us in making a fire, and we chat with them, until their parents call them to their home. We share a bottle of Martini, while nightingales (Luscinia megarhynchos) are singing in the thicket, and tree frogs (Hyla arborea) are calling, a penetrating ”rekke-rekke-rekke”, from nearby waterholes. A lovely end to a fine day!