Rocks and boulders

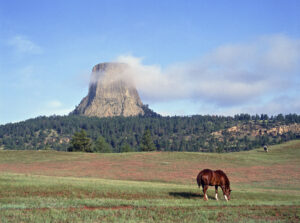

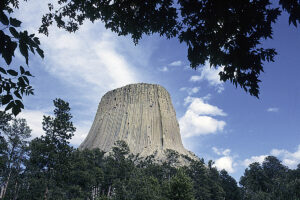

Devil’s Tower is an amazing rock formation in north-eastern Wyoming, 265 m tall, consisting of mainly 6-sided, vertical columns of solidified magma. The rock is described in depth below under the United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This striking rock, situated between the islands Vágar (in front) and Mykines, Faroe Islands, is named Tindholmur. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Deposited minerals add gorgeous colours to this rock wall at Lisong Hot Springs, Sinwulu River, eastern Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

White kittiwakes (Rissa tridactyla), breeding on dark rocks off Rauðanupur (‘Red Cliff’), northern Iceland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cumulus clouds, gathering around the Sella Mountains, Dolomites, northern Italy. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“I followed him [Luigi] round to the back of the house, where the fields swept up to the edge of the woods in all their stoniness. Many of them could scarcely be called stones. They were rocks and boulders, which had come rolling down off the mountain. It was like looking out on a parable.

“I want those fields cleared of stones,” he said, quite casually. “All of them. I should start with that one up there. The others will help you with the big ones, when they’ve finished what they’re doing, in a week or two. There’s a cart over there,” he indicated a vehicle with solid wooden wheels and sides made from plaited stems of osiers. It looked like a primitive chariot.

“What shall I do with them,” I said, “when I’ve put them in the cart, the stones?”

“You can do what you like with them,” he said, “as long as they don’t stop on my land.”

Then he looked at me, and seeing that I was genuinely puzzled, he gave me the same kind of foxy grin that Sergeant-Major Clegg used to when he announced to us that there would be no weekend leave.

“You can throw them over the cliff,” he said. “You can start now.”

From the book Love and War in the Apennines (1971), by English author Eric Newby (1919-2006).

“The rocks are not so close akin to us as the soil; they are one more remove from us; but they lie back of all, and are the final source of all. I do not suppose they attract us on this account, but on quite other grounds. Rocks do not recommend the land to the tiller of the soil, but they recommend it to those who reap a harvest of another sort – the artist, the poet, the walker, the student and lover of all primitive open-air things.”

American author and conservationist John Burroughs (1837-1921), in his essay The Friendly Rocks, from Under the Apple-Trees, 1916.

Limestone caves

Wonderful rock formations are created in limestone caves under certain pH conditions. Rain water, which contains carbon dioxide, seeps through cracks in the limestone and dissolves tiny amounts of calcium carbonate and other minerals. Over the millennia, various types of calcium bicarbonate structures are formed in the cave.

The commonest types are stalagmites (Greek for ‘dropping’ or ‘trickling’), which rise from the floor of the cave, when water drips from the ceiling, causing the minerals to be deposited. The corresponding type that hangs down from the ceiling is called stalactites. Often, the two types connect to form columns.

Limestone formations, including columns, stalactites (hanging) and stalagmites (standing), Sung Sot Cave (‘Surprise Cave’), Halong Bay, Vietnam. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

What do you think that this stalagmite in the Sung Sot Cave resembles? (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stalactites and stalagmites, Carlsbad Caverns, New Mexico, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pointed stalactites, Carlsbad Caverns. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Glacial erratics

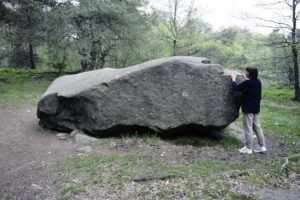

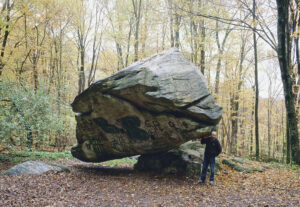

This term covers large boulders, left by glaciers during the last Ice Age, 10,000 to 15,000 years ago. They are a very common sight in Denmark and southern Sweden, and there are also many in North America.

One of these boulders inspired Danish poet Steen Steensen Blicher (1782-1848) to write the following in his short-story Brudstykker af en Landsbydegns Dagbog (’Fragments of the Diary of a Parish Clerk’), from 1824: ”Thus I recognize many a tree, many a heather-covered hill, and even the dead boulders, which stand here unchanged for millennia, watching one generation after another grow up and vanish.”

Damestenen (‘Lady’s Boulder’), or Hesselagerstenen (‘The Hesselager Boulder’), Funen, is Denmark’s largest erratic boulder, with a circumference of 45 m, a volume of c. 370 m3, and a weight of about 1000 tons. As legend has it, an ogress, living on the island of Langeland, who was annoyed by the tolling bells of Svindinge Church, hurled this huge boulder, aiming at the church spire, but missed.

(Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Kroppkaka Stone is a glacial erratic that has been eroded to an almost globular form, resting on a number of smaller stones near the village of Folkeslunda, on the island of Öland, Sweden.

As legend has it, a giant named Wälter lived on Öland with his wife. One day, they were arguing as to where the centre of Öland might be, and, as they were very skilled at throwing stones, they decided to use this method. They knew that the giant was able to throw his large round stone exactly as far, as the wife was able to throw the lesser stones she was carrying in her apron. The wife now went to the northern tip of the island, from where she threw her stones southward, as far as she could, whereas Wälter, from the southern point of the island, with all his might threw his one large stone northward. Later, they met at Folkeslunda, and, as it turned out, the stones had all landed on the exact same spot, with the large stone resting on the smaller stones. They now knew that they had found the centre of the island.

The name Kroppkaka Stone is due to the almost globular form of this rock, which resembles a kroppkaka, a traditional Swedish dish, consisting of balls made of potato and wheat flour, with a filling of salt and onions, and beef, pork, or bacon.

Hans and Ann-Christine Lomosse at the Kroppkaka Stone, Öland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

According to legend, Slingestenen (‘The Sling Boulder’), an erratic boulder on the island of Bornholm, Denmark, was hurled at Bodil’s Church. An ogre, living on the islet of Christiansø, aimed at the church, using a silver cord, which left an indent around the boulder. He missed his goal, and the boulder landed in the nearby Paradisbakkerne.

Slingestenen. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

‘Rocking stones’ are erratic boulders, resting on the bedrock, which can be moved a little up and down with very little force, often merely by pushing with one hand. Once there were several of these boulders on Bornholm, but most of them have lost the ability to ‘rock’.

Rokkestenen (‘The Rocking Stone’), Paradisbakkerne, Bornholm. It lost the ability to be moved, but the authorities have cheated, using force to make it move again, so as not to lose this tourist attraction. They didn’t do a nice job, note that the boulder is resting on an ugly, square stone, which doesn’t look natural at all. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Elsebeth Norup, attempting to move Rokkestenen (‘The Rocking Stone’) in Rutsker Højlyng, Bornholm, but it has lost the ability to be moved. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stony coast with glacial erratics, Vivesholm, Gotland, Sweden. The buildings in the background are fishermen’s sheds. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Erratic boulder, Møn, Denmark. It has been split due to severe cold. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hønen (‘The Hen’), a glacial erratic, balancing precariously on the bedrock, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This glacial erratic near Lanesborough, Massachusetts, United States, is resting on a very small area of an underlying rock. It has been aptly named ‘Balance Rock’. (Photo Søren Lauridsen, copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Earth pyramids

In many areas around the Earth, cone-shaped pillars are formed in volcanic layers, or in moraine clay or gravel, which was deposited during the last Ice Age. In dry weather, these layers are hard as stone, but when it rains, it becomes softer and begins to erode away. However, larger rocks were also deposited by the volcanoes and the glaciers, and under such stones the soil is protected from the rain. Over the years, the surrounding soil is eroded away, and beneath the rocks majestic pillars are formed, often rising steeply out of the soil. Such structures are called earth pyramids.

Earth pyramids, carved out along a river, Pang, Ladakh, northern India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The volcanic tuff layer in the Zelve Valley, Cappadocia, central Turkey, has been eroded into earth pyramids. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These earth pyramids in the Zelve Valley strongly resemble stinkhorn fungi (Phallus). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Eroded tuff landscape with earth pyramids, Çavuşin, Cappadocia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Earth pyramids, Segonzano, Dolomites, Italy. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Remarkable rocks and boulders around the world

Below is a collection of pictures, depicting remarkable rocks or rock formations, arranged alfabetically according to country name. Other pictures may be seen on the page Nature: Nature’s artwork.

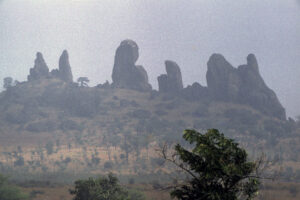

Cameroun

Misty rock formations, Kapsiki Mountains. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

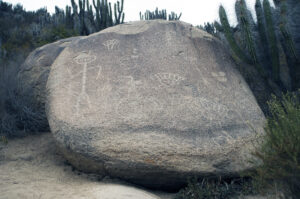

Chile

Boulder with petroglyphs, dating back from the El Molle Culture (c. 300-700 A.D.), Valle del Encanto, Ovalle. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

China

These strange rock formations in ‘The Stone Forest’, east of Kunming, Yunnan Province, resemble aliens. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Peculiar limestone formations, Mei Shan (‘Plum Mountains’), Guizhou Province. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Denmark

The coastal rock in the pictures below, off the coast of Bornholm, was formed by rainfall, waves, and wind. This formation is called Kamelhovederne (‘The Camel Heads’), although one of the figures resembles a wolf, rather than a camel. In the lower picture, a variety of sea mayweed, Matricaria maritima var. retzii, and a yellow lichen, are growing atop the rock.

(Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lyseklippen (‘Candle Rock’) is a 22 m tall, columnar rock at Helligdomsklipperne, Bornholm. A herring gull (Larus argentatus) is nesting on top of the rock. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Another columnar rock at Helligdomsklipperne is called Mågebænken (‘Gulls’ Bench’). A rowan (Sorbus aucuparia) has sprouted in a crack in the rock. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

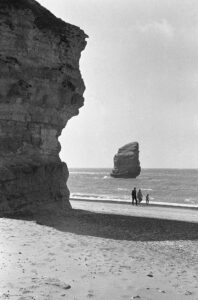

Skarreklit was a remarkable limestone cliff in Thy, which fell into the sea in 1978. To the left another limestone cliff, Bulbjerg. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

There was a colony of kittiwakes (Rissa tridactyla) on Skarreklit. This small gull is described below under Iceland. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stone fence in evening light, Møn. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Old road marker from 1847, Elling Wood, north of Horsens, Jutland. Green algae are growing on the stone. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Near the village of Tappernøje, southern Zealand, are the remains of two ancient roads, one built on top of the other, across the rivulet Hulebækken, Broskov. The lower one (in front) is an elaborate structure, dating back to the Iron Age (c. 300-400 A.D.). On top of this, where the person is standing, a much less sophisticated road was built during the Middle Ages (c. 1300-1400 A.D.

(Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Egypt

Rocks in morning light, Djebel Musa (Mount Moses), Sinai. On this mountain, Moses, according to The Book of Exodus, received the two tablets with the Ten Commandments inscribed. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Faroe Islands

Risin og Kellingin (‘The Giant and the Hag’) are two monoliths off the north-westernmost mountain Eiðiskollur on Eysturoy, Faroe Islands. A Faroese legend relates how the giants in Iceland decided that they wanted to drag the Faroe Islands to Iceland. So a giant and his hag of a wife were sent down to do the job.

When they reached Eiðiskollur, the giant stayed in the sea, while the hag climbed up the mountain with a rope to tie the islands together, so that she could push them onto the giant’s back. However, when she attached the rope and pulled, the northern part of Eiðiskollur split. They struggled through the night, but the base of the islands was firm and could not be moved.

Now, if the sun shines on a giant, he or she turns to stone. During their struggle, they didn’t notice time passing, and as dawn broke they were turned to stone on the spot. There they have stood ever since, staring longingly across the ocean towards Iceland. Risin, 71 m tall, is furthest from the coast, whereas Kellingin, 68 m tall, is closer to land, standing with her legs apart.

Mist blurs the outline of Risin og Kellingin, seen from Tjørnuvik, Streymoy. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

France

Once upon a time, people were living in this house, built into rocks along Gorge du Tarn, Cévennes. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Iceland

The kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla) is a small gull, which is widely distributed in Arctic seas, breeding in colonies on steep rocks or cliffs, where each pair builds a nest, consisting of plants and seaweeds, on a narrow ledge. As a breeding bird, this species is found southwards to the Kuril Islands, southern Alaska, Newfoundland, the British Isles, and France, with scattered colonies in Portugal and Spain. In winter, it disperses to a huge area in subarctic and temperate seas.

The generic name is derived from the Icelandic name of the bird, rita, whereas the English name was given in allusion to its call. The specific name is from Ancient Greek tridaktylos (‘three toes’), referring to the fact that this species is missing the small, back-pointing fourth toe, which most other gull species possess.

In North America, this species is called black-legged kittiwake to differentiate it from its near relative, the red-legged kittiwake (Rissa brevirostris), which breeds on small islands in the far northern Pacific.

White kittiwakes, breeding on dark rocks off Rauðanupur (‘Red Cliff’), northern Iceland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Millions of years ago, volcanic activity in today’s northern Iceland brought fluid basaltic lava to the surface, where it formed a plateau. As the lava cooled, it contracted and fractured in a similar way to drying mud. As the lava cooled further, these cracks penetrated downwards, forming 6-sided (sometimes 4-, 5-, and 7-sided) columns. Further volcanic activity since pushed some of the columns into a horizontal position.

Some of these formations, named Hljoðaklettar, have withstood erosion from the river Jökulsá á Fjöllum River. Hljoðaklettar means ‘Echo Rocks’, so named due to the peculiar acoustics of the area, which produce echoes.

Following the formation of these columns at Hljoðaklettar, further volcanic activity pushed them into a horizontal position. The tree in the foreground is arctic downy birch (Betula pubescens var. pumila). (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

An alpine lady’s mantle (Alchemilla alpina) adds a touch of colour to the otherwise sombre Hljoðaklettar rocks. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Vertical basaltic columns, Aldeyarfoss, Aldeyjardal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hardened lava, Þingvellir. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hardened lava from a volcanic eruption which took place about 15 years previously, Krafla, near Lake Myvatn. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus) is a large wader, belonging to the curlew genus, of the large snipe family (Scolopacidae). It breeds in Arctic and Subarctic areas in North America, Greenland, Iceland, northern Scotland, Scandinavia, Finland, north-western Russia, and at scattered locations across Siberia. The name whimbrel is an imitation of its call, a number of rattling tones.

Whimbrels, resting on a lava rock, Aðaldal, northern Iceland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

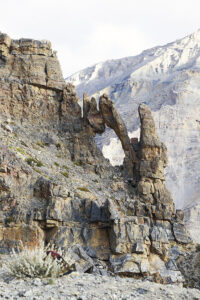

India

Ladakh is a barren land in north-western India. Geologically it constitutes a part of the Tibetan Plateau. This outlying part of the Himalaya is characterized by sharply rising sedimentary rocks, which have been eroded into any imaginable shape.

Eroded rocks near Sumda. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Eroded rocks, creating a ‘window’, near Pang. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this rocky area near Lato, rain and meltwater have eroded away the softer parts of the rock, leaving the columbs and what will perhaps be columbs in the future. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Evening shadows on rocks, Lamayuru. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tilted sedimentary rocks, Stok La. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Evening light and shadows, near Pang. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

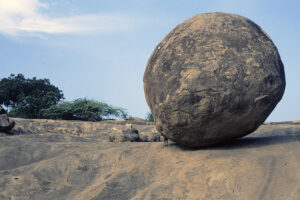

Krishna, who is the eighth avatar (incarnation) of the great Hindu god Vishnu, is a very popular deity, identified by his blue skin. He is often depicted, playing on his flute, accompanied by his greatest love, Radha, or with gopis, beautiful female herders, whom he was fond of seducing.

Krishna grew up with a herdsman, well protected against a cruel king, Kansa, who was killing man-children, as a fortune teller had warned him that he would be overthrown by a young man. A divine voice warned Krishna, who took shelter with the herdsman. When he had reached manhood, he killed the evil king and liberated the people.

Krishna and other Hindu gods are presented on the page Religion: Hinduism.

The name of this huge boulder, resting on a flat rock near Mamallapuram, Tamil Nadu, South India, is ‘Krishna’s Butterball’. The goat beneath the boulder gives an impression of its size. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Jain pilgrim, clad in an orange lungi (sarong), and carrying a metal jar with sacred water and a flower garland, makes his way up the steep rock Vindhyagiri, Sravanabelagola, Karnataka, on whose top a gigantic statue of the Jain saint Bahubali (Gomateswara) is situated. This statue is shown on the page Religion: Jainism. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

At the foot of Vindhyagiri, clothes have been spread out on a flat rock to dry. A woman is washing other clothes in a pool beneath the rock. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Changabang (6864 m) is a striking mountain, consisting of very pale granite, Nanda Devi National Park, Uttarakhand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Over the millennia, the Kalhatti Waterfall, in the Nilgiri Mountains, southern India, has carved out a circular depression in the rock. The flowers to the left are marigolds (Tagetes). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In 2007, together with Indian forester Ajai Saxena and his wife Madhu, I undertook a hike in the Great Himalayan National Park, Himachal Pradesh. At several spots, the trail along the Tirthan River had been washed away by heavy monsoon showers, and new ‘paths’ had been constructed, many of them leading through the river itself. This hike is described in detail on the page Plants – Plant hunting in the Himalaya: Abode of the deodar.

Along the Tirthan River, we had to jump from one rock to the next, and to balance on logs along a rock wall. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Indonesia

This Hindu temple, named Tanah Lot, has been built on a rock off the west coast of Bali. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ireland

Rock formations, Cliffs of Moher. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The ancient road in the picture below, on Black Head, western Ireland, is marked by upright slabs of rock. It has been erroneously labelled as a part of the famous Famine Road, built during the Great Famine, a period of mass starvation and disease in Ireland 1845-1852. However, this particular road was there long before the construction of the Famine Road, according to some sources maybe even a thousand years before.

Morning sun illuminates the slabs along the old road, Black Head. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Italy

The Dolomites is a dramatic mountain area of numerous sharp peaks, situated in north-eastern Italy. These mountains consist of a carbonate rock, named dolomite. This mineral was named for French geologist Déodat Gratet de Dolomieu (1750-1801), who was the first person to describe it.

Sella group, seen from Passo Gardena (2136 m). The highest peak in this group is Piz Boè (3151 m). (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Evening light on Monte Averau (2649 m), the highest mountain in the Nuvolau group, seen from Passo di Valparola (2192 m). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Evening light on mountains around Passo di Valparola. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Layered coastal rock, Terrasini, near Palermo, Sicily. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Jordan

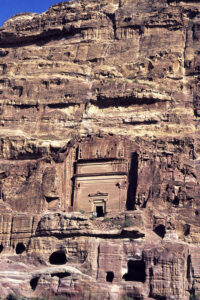

Petra is an area of dramatic rocks near the mountain Jabal al-Madbah in southern Jordan. This area has possibly been inhabited as far back as 7000 B.C. Perhaps as early as the 4th Century B.C., the nomadic Nabataeans, in Arabic al-Anbat, settled here and established a major trading centre, based on trade with incense. A city named Raqmu evolved, which, at its peak, may have had as many as 20,000 inhabitants.

As sea trade routes emerged, the importance of Raqmu declined, and in 106 A.D. it was conquered by the Romans, who renamed the Nabataean kingdom Arabia Petraea (‘Rocky Arabia’). In the Byzantine era, several Christian churches were built in Petra, but the city continued to decline, and by the time the Muslims gained power in Jordan, the city had already been abandoned. Only a handful of nomads resided here.

The area remained unknown to the West, until it was rediscovered in 1812 by Swiss traveller and orientalist Johann Ludwig Burckhardt (1784-1817), who travelled in Arabia under the name Sheikh Ibrahim Ibn Abdallah.

Access to Petra is through a narrow gorge. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dwellings and temples were carved into the rocks of Petra. The scale is indicated by the people. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Multi-coloured rocks, Petra. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

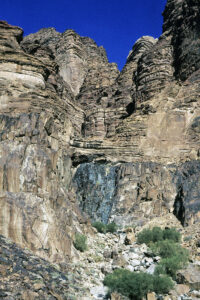

Wadi Rum, in Arabic Wadi Ramm, is a valley cut into sandstone and granite rocks in southern Jordan – the country’s largest wadi. Ramm is the Arabic term for the Romans, but some believe that the name is a corruption of an earlier name of the area, Iram dhat al-Imad (‘Iram of the Pillars’, or ‘Iram of the Tentpoles’), a lost city mentioned in the Quran, and also in The Book of One Thousand and One Nights. A popular name is Wadi al-Qamar (‘Valley of the Moon’).

Rocks, Wadi Rum. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kenya

Three species of zebra live in Africa. The commonest and most widespread is the plains zebra (Equus quagga, previously known as E. burchellii). It was formerly far more widespread, but today the range is fragmented, with scattered populations of 5-6 subspecies, found from southern Ethiopia southwards through eastern Africa to northern Namibia and north-eastern South Africa.

The three zebra species are described on the page Nature: Nature’s patterns.

Plains zebras, subspecies boehmi, in front of basalt columns, Hell’s Gate. These structures are described above, under Iceland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The African fish-eagle (Haliaeetus vocifer), which is widely distributed in sub-Saharan Africa, always lives near water. This iconic raptor is the national bird of no less than three countries: Zambia, Zimbabwe, and South Sudan. This species was described by French naturalist François Levaillant (1753-1824), who named it vocifer (’the one who has a penetrating voice’) – a most suitable name for this eagle, whose scream often resounds over African wetlands.

This African fish-eagle is resting on a huge boulder near Adamson’s Falls, Tana River, Meru National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kyrgyzstan

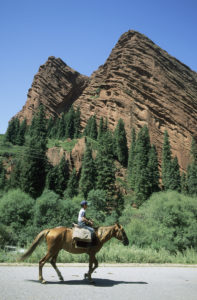

The rocks of Djeti-Ögüz (‘Seven Bulls’) is a natural monument, located in the Issyk-Kul Province. A local legend relates, how these rocks got their name.

A long time ago, a khan (chief) had a beautiful wife. Another khan fell in love with the wife and stole her from her husband. This caused a brutal war to break out between the khans. The khan, who had abducted the wife, asked a wise man what to do. He advised the khan to kill the wife, so that her former husband could never take her back.

The khan now organized a large fiest, ordering seven bulls to be killed, after which he killed the wife. However, huge splashes of blood gushed from her heart, drowning the khan and his servants, and washing away the seven bulls. When they finally came to rest, the bulls turned into a red stone formation, resembling the backs of seven bulls. (Source: advantour.com/kyrgyzstan/legends/jety-oguz)

Horse rider, passing by Djeti-Ögüz. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Namibia

The varied and interesting nature in Namibia is described on the page Countries and places: Namibia – a desert country.

Eroded rocks in morning light, Spitzkoppe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Alternating temperatures have caused this rock near Spitzkoppe to crack into thin flakes, resembling the layers of an onion. Further erosion is made by rain and wind. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nepal

Eroded cliff, Upper Marsyangdi Valley, Annapurna. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Patterns on an eroded rock wall, Chiruwa, Tamur Valley, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cattle, grazing in front of eroded rocks, Manang, Upper Marsyangdi Valley, Annapurna. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

New Zealand

Several high coastal rocks near Muriwai Beach, North Island, are home to a large colony of Australian gannets (Morus serrator). This species is described on the page Sleep.

Rough sea beneath the rocks at Muriwai Beach. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Norway

Granite rocks in Lake Femunden, Hedmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Philippines

The picture below shows limestone rocks in a forest of Pinus kesiya var. langbianensis (previously known as Pinus insularis), Sagada, Luzon, northern Philippines. Previously, Bontoc tribals in this area placed their deceased relatives in coffins, which were stacked in caves in such limestone rocks. Today, most Bontocs are Christians, and this old custom is no longer utilized. The picture was taken in 1984, when the coffins were already in various stages of decay. Other pictures, depicting such coffins, may be seen on the page Culture: Graves.

(Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Scotland

Old stone fence in morning sun, Drymen, Loch Lomond. The upper part of the fence consists of upright slabs, making it difficult to climb over it. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

South Africa

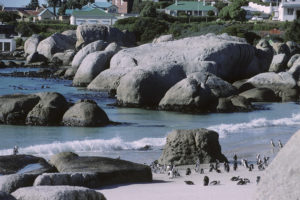

Boulders is the name of a coastal area at Simonstown, near Cape Town, with many rounded boulders, among which a breeding colony of jackass penguins (Spheniscus demersus) have made their home. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The penguins at Boulders have become so accustomed to people that they ignore them. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rock formation in morning light, Augrabies National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The klipspringer (Oreotragus oreotragus) is a small antelope, which lives in rocky habitats. The outer keratin layer on its hooves is rubber-like, causing them to have a tremendously firm grip on steep surfaces.

It is widely distributed, from eastern Sudan and Eritrea southwards through eastern Africa to north-eastern South Africa, and also in western Angola, Namibia, and western South Africa. Small remnant populations exist in western Central African Republic and Nigeria. About 11 subspecies have been described.

It prefers rocks with growth of scattered bushes, where it can seek shelter from enemies, including eagles. It has been observed as high as 4,500 m altitude on Mount Kilimanjaro.

The klipspringer is an animal of rocky habitats. These pictures show Cape klipspringer, subspecies oreotragus, Augrabies National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spain

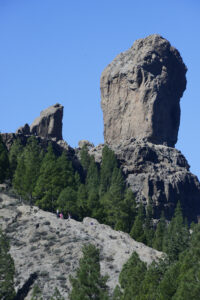

This spectacular rock in central Tenerife, Canary Islands, has been dubbed Los Roques de Garcia, and popular names include ‘God’s Finger’ and ‘The Stone Tree’. The mountain in the background is the volcano Teide, at 3,715 m the highest peak in the archipelago. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Roque Nublo (‘Rock in the Clouds’) is a striking volcanic formation in central Gran Canaria. It is 67 m high, and its top is 1,813 m above sea level – the third-highest peak on the island, after Morro de la Agujereada (1,956 m) and Pico de las Nieves (1,949 m).

(Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Roque Nublo is popular among rock climbers. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Roque Nublo in evening light. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Another striking rock formation in the Roque Nublo area. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These peculiar rock formations in the mountain chain El Torcal de Antequera, Andalusia, consist of Jurassic limestone, about 150 million years old. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Roque Bentayga is a rock formation in central Gran Canaria, located within the volcanic caldera of Tejeda. Its top is 1,414 m above sea level. Near the rock is an old settlements of the Guanches, the aboroginals of the Canary Islands, consisting of around a hundred caves with rooms, besides silos, and a burial place.

Towards evening, clouds gather around Roque Bentayga. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Roque Bentayga in evening sun. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Morning light on El Rejo, a rock formation surrounded by subtropical evergreen laurel forest, La Gomera, Canary Islands. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rock formations, Caldera de los Marteles, Gran Canaria. The rock in the background is Roque Nublo (1,813 m) (see above). (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

‘Window’ in a rock, Caldera de los Marteles. Note the person. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

During the last hundred years, the griffon vulture (Gyps fulvus) has declined in large parts of Europe, but there is still a viable population in Spain.

Griffon vulture on its nesting site, situated on a rock ledge, Valle Hecho, Aragon. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Evening light on a rock, utilized by griffon vultures as a night roost, Salto el Gitano, Parque Natural de Monfragüe, Extremadura. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This rock wall, Risco de la Merica, Valle Gran Rey, La Gomera, Canary Islands, is home to the endemic La Gomera giant lizard (Gallotia bravoana). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Roque Palmès and misty mountains, central Gran Canaria. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sri Lanka

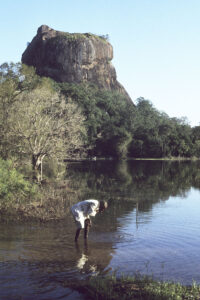

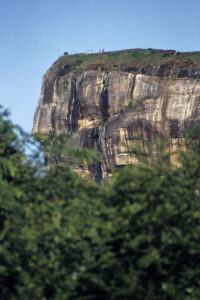

Usually, construction of a fortress atop Sigiriya (‘Lion Rock’), eastern Sri Lanka, has been ascribed to the Sinhalese King Kasyapa, or Kassapa (ruled 473-495 A.D.) – a terrible man, who killed his own father and tried to kill his brother Moggallana, who was the rightful heir to the throne. Moggallana escaped to India, but later returned to Sri Lanka with an army. A huge battle ensued, during which Kasyapa was killed.

Archaeological excavations, however, have revealed that parts of the fortress were built long before Kasyapa’s reign. (Source: R. Beny & J. L. Opie 1970. Island Ceylon. Thames & Hudson, London)

Ancient paintings, depicting beautiful noble women, are found on the rock wall. A selection is shown on the page Culture: Folk art around the world.

Sigiriya (‘Lion Rock’). Note the people on the top in the bottom picture. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sweden

Late afternoon light on coastal limestone formations, called raukar, formed by sea erosion, Byrum, Öland. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

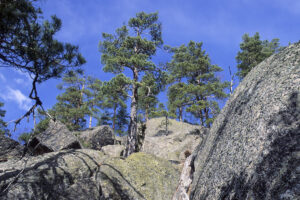

Forest of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris), growing among huge rocks, Tiveden, Närke. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The common guillemot (Uria aalge), in America known as common murre, is a species of auk with a circumpolar distribution, found in Arctic, sub-Arctic, and temperate waters, southwards to Portugal, Sakhalin and the Kurille Islands, northern California, and Nova Scotia.

Limestone cliff with a colony of common guillemot, Stora Karlsö, Gotland. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Taiwan

These flat coastal rocks at Laomei, near Cape Fugueijiao, northern Taiwan, have been eroded into wedge-shaped, more or less parallel rocks, covered in a species of sea lettuce, Ulva compressa. Sea water is washed into hollows beneath the rocks, sprouting up geysir-like through cracks. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

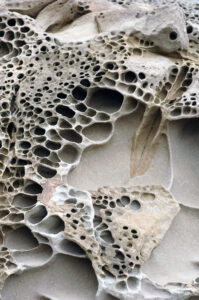

Eroded formations of Nanya Sandstone with layers of oxidized iron, Nanya Peculiar Rocks, northern Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

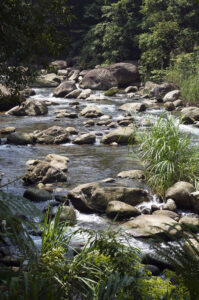

Stony bed of the Penglai River, Lion’s Head Mountain, northern Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Eroded coastal rocks, forming a pattern of concentric circles, Sandiao Cape, north-eastern Taiwan. Note the anglers. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Patterns on a rock face, Shakadang River, Taroko National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Coastal rocks, Jialeshuei, Kenting National Park, southern Taiwan. Other rocks from this area are shown on the page Nature: Nature’s art. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This opening in coastal rocks at Eluanbi, Kenting National Park, southern Taiwan, which consist of fossilized coral, is called ‘The Sea Pavillon’. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These coastal rocks have been eroded into formations, which resemble giant mushrooms. Against the light, they form a stark contrast to the paler rock base. – Bitou Cape Trail, northern Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Patterns on a rock wall along the Tacijili River, Taroko Gorge. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Coastal rocks, tilted during volcanic activity, Sandiao Cape, north-eastern Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Coastal rocks, Xiao Yeliou, eastern Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Coastal rocks with anglers, Yeliou Geopark, northern Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

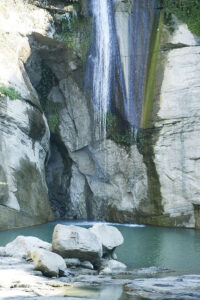

Cing Yun Waterfall, south of Alishan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tanzania

Kopjes are isolated rocky outcrops, which, somewhat wantonly, pierce the African savanna here and there. Incidentally, they are the remains of ancient, eroded mountains. To the Boer, when they migrated to Southern Africa in the 1700s, these outcrops resembled bald heads, so they named them kopjes (‘heads’ in Dutch).

These rocky outcrops in Serengeti National Park, have been dubbed Simba Kopjes (‘Lion Heads’). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this picture, a herd of kongoni (Alcelaphus buselaphus ssp. cokei) are passing in front of Simba Kopjes. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young lions (Panthera leo), resting on Simba Kopjes. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus), surveying the surroundings from a formation in Serengeti National Park, named Gol Kopjes. A male pallid harrier (Circus macrourus) is passing by. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Turkey

Eroded rock formations, consisting of volcanic tuff, Göreme, central Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

United States

The states of Utah and Arizona, and the western part of Colorado, south-western United States, are home to extremely dramatic landscapes, displaying rocks in almost every imaginable form and shape. The following pictures show a selection of these rocks.

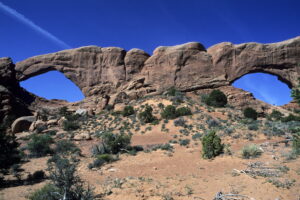

The presence of natural arches in Arches National Park, Utah, is caused by thick layers of salt, deep in the underground. These layers are unstable because of the tremendous weight of sediments, resting on them. The layers sometimes move, causing the rocks in the overlaying sediments to crack, often along parallel lines. In these cracks, alternating temperatures loosen small bits of rock, which are removed by rain and wind. In some places, underlying, softer sediments are eroded away, leaving natural arches of harder material.

If you want to see the slender and fragile Landscape Arch, you probably have to do so soon. It may fall anytime. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Delicate Arch is balancing at the edge of an abyss, looking as it could fall any moment. In the background the La Sal Mountains. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Delicate Arch, illuminated by late afternoon sunshine. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Delicate Arch in evening light. Note the persons sitting under the rock. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Broken Arch resembles two giant lizards, one biting the other one’s snout. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Double Arch. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

South Window (left) and North Window. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mesa Arch in morning light, Canyonlands National Park, Utah. This stunning natural arch was created by rain water, eroding away the rock layer around the arch. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These rocks in Canyonlands National Park have been named The Needles. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This huge rock formation in Capitol Reef National Monument, Utah, has been named Egyptian Temple. Washed-out minerals are seen in the riverbed. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A unique landscape is found in Bryce Canyon National Park, southern Utah, displaying spires, towers, and other fantastic figures in brilliant red and yellow colours. The local Paiute people called the figures ’The Legendary People’, and, according to their mythology, they were people, turned into stone by the wizard Coyote, whom you may read more about on the pages Animals: Dog family, and Plants – Plants in folklore and poetry: Ranunculus).

The first white settler here was Ebenezer Bryce, whom the national park is named after. He grazed his cattle on the plateau above the gorge and had an entirely different opinion about this magnificent landscape: “A hell of a place to lose a cow.”

The figures are shaped by rivulets and rain water, eroding the soft sediment along the edge of a fault. This erosion caused many tiny gorges to emerge, through which the sediment could be washed out more quickly, leaving only ‘fins’ of harder material, consisting of a mixture of limestone, siltstone, dolomite, and mudstone, filled with holes and cracks. As the park is situated at a high altitude (c. 2300 m), the climate is harsh. In the holes and cracks, rain water freezes and expands, eroding away even more sediment. Only the hardest material remains, often shaped to the strangest forms. In American, these figures are called hoodoos.

Morning light (top) and evening light on eroded rocks, Bryce Canyon National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Morning sun on rocks, seen from Sunrise Point, Bryce Canyon. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This remarkable rock in Bryce Canyon has been sculptured by wind and water. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

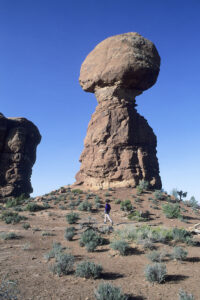

Rocks, balancing on other rocks, often rather precariously, are found in numerous locations in the United States.

Balancing rock, consisting of tuff, Chiricahua National Monument, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This balancing rock in Chiricahua National Monument is aptly named Mushroom Rock. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Balancing rock, resembling a head with an old-fashioned bonnet, Arches National Park, Utah. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Over time, this rock in Arches National Park will also become balancing. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These balancing rocks in Goblin Valley State Park, Utah, have been carved in Entrada Sandstone by erosion from wind and rain. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Balanced Rock, at North Salem, New York State, is a pre-Columbian dolmen, consisting of a 90-ton granite boulder, which is balancing atop several slabs of granular quartz. Geologists have labeled it an accidental glacial erratic, but it sits precisely over a major magnetic anomaly, and brilliant golf-ball sized lights have repeatedly been photographed circling it.

Such structures show links with electro-magnetic energies and increased crop production. This interesting theory, which was proposed by my late friend John Burke, is described in depth on the page Book – Seed of Knowledge, Stone of Plenty: Understanding the Lost Technology of the Ancient Megalith-Builders.

Balanced Rock is balancing atop several slabs of granular quartz. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

From this angle, Balanced Rock resembles the head of a turtle. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hickman Natural Bridge in Capitol Reef National Monument, Utah, is a 40 m long and 37 m tall natural bridge, named for Joseph Hickman, a local school administrator and Utah legislator who was an early advocate of the Capitol Reef area. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This remarkable rock north of Monticello, Utah, has been dubbed Church Rock. A more suitable name would be ‘Stupa Rock’, as it clearly resembles this Buddhist structure. In the background La Sal Mountains with Mount Peale (3868 m). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In Monument Valley, Arizona, rainfall and wind have eroded rocks into bizarre forms.

This picture shows The Totempole, which seems to defy gravity. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This rock formation, called Three Sisters, is silhouetted against the evening sky. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

East Mitten (left) and Merrick Butte in evening light. East and West Mitten were named due to their outline, resembling mittens, complete with a separate pocket for the thumb. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Blue Mesa, situated in Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona, consists of thick layers of grey, blue, purple, and green mudstone, deposited approximately 220 million years ago. This area abounds with petrified tree trunks.

Eroded gully with broken petrified logs, Blue Mesa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

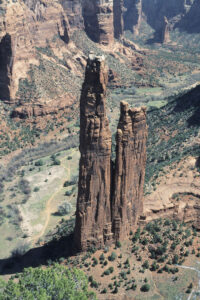

Spider Rock is a striking rock formation in Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Arizona. According to Navajo legend, this rock is the abode of Spider Woman, who wove the web of the universe. She taught the Navajo how to weave, how to create beauty in their life, and how to spread the ‘Beauty Way’ – the teaching of balance within the mind, body, and soul.

Spider Rock, Canyon de Chelly. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bluffs, Torrey Pines State Beach, California. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flat coastal rock, Torrey Pines State Beach. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

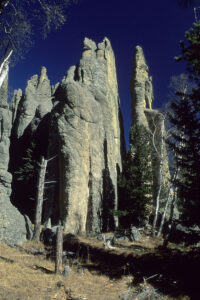

Eroded rock formations, Harney Peak, Black Hills, South Dakota. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

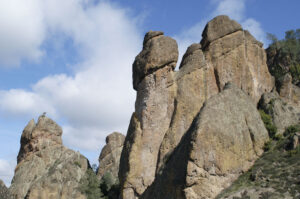

Eroded rocks, Pinnacles National Park, California. The tree in the upper picture is a valley oak (Quercus lobata), draped with Usnea lichens. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum), growing over a rock, Sequoia National Park, California. This magnificent tree is described on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Crazy Horse Memorial is a monument under construction, which is going to depict the Oglala Lakota warrior Crazy Horse, riding a horse and pointing to his tribal land. It is situated in the Thunderhead Mountain, South Dakota, on land considered sacred by the Oglala Lakota people. The memorial was commissioned in 1948 by Lakota elder Henry Standing Bear, undoubtedly to outdo the famous Mount Rushmore monument nearby, which depicts four American presidents, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln.

Initially, the work was in the hands of Polish-American designer and sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski (1908-1982).

Still, the sculpture is far from completed. When finished (if that should ever happen), the final length will be 195 m and the height 172 m. The outstretched arm will be 80 m long, the opening under the arm 30 m high, and the index finger 9 m long. The face of Crazy Horse, which was completed in 1998, is almost 27 m high. By comparison, the heads of the presidents at Mount Rushmore are 18 m high.

The sculpture of Crazy Horse, as of 1999. The head of his horse is drawn on the rock. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This model shows the monument, as it was planned to be. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Eroded coastal rocks, Salt Point State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Morning light on a spectacular rock with alternating dark and light sedimentation, Mesa Verde, Colorado. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Eroded rocks around ‘Hole-in-the-Wall’, Mohave National Preserve, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The beautiful patterns on this rock wall in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, North Carolina, are created by rain water, following a heavy shower. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Green algae, growing on eroded coastal rocks, Montaña de Oro State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

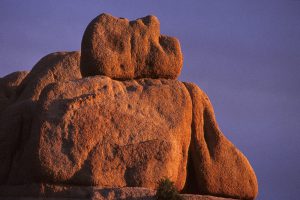

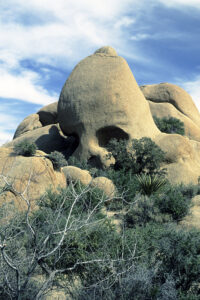

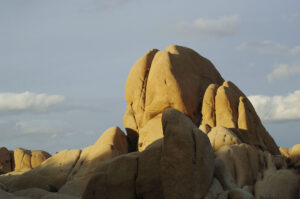

Joshua Tree National Park in the Mohave Desert, eastern California, contains several interesting rock formations. Four examples are shown below.

Morning sun illuminates an eroded rock, resembling the head of a sleeping giant. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Another formation in the national park is Skull Rock – a descriptive name of this eroded rock. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Morning light on Jumbo Rocks, which consist of Monzo granite. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A juniper (Juniperus) has sprouted among these Monzo rocks. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Devil’s Tower is a rock formation in north-eastern Wyoming – presumably the eroded remnant of a laccolith, a large mass of magma, which is intruded through sedimentary rock. As the magma cooled, 6-sided (sometimes 4-, 5-, and 7-sided) vertical columns formed. This amazing rock rises dramatically above the Belle Fourche River, 265 m high from base to summit.

For hundreds of years, this rock has been sacred to local peoples, including Lakota, Cheyenne, and Kiowa, and it appears in the mythologies of several other tribes. One legend relates that a giant bear was pursuing a small band of people who, by magic or otherwise, were able to find shelter on top of the rock, just out of reach of the bear. The deep furrows on the side of the rock were made by the angry bear’s claws as it vainly attempted to climb it.

Today, the rock is the site of tribal vision quests and other rituals, and in the surrounding grasslands, Sun Dances and other tribal ceremonies are performed. Vision quests are described in depth on the page Book: Seed of Knowledge, Stone of Plenty, Chapter 3.

Devil’s Tower rises dramatically above the surrounding landscape. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Devil’s Tower is popular among rock climbers. In this picture, climbers scale some of the columns. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Eroded rocks, Red Rock Canyon State Park, Mohave Desert, California. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Vietnam

A local legend relates that when the Vietnamese people had just begun to form a nation, their young country was invaded by hostile foreigners. To assist the Vietnamese in defending their country, the gods sent a family of dragons as protectors. These dragons began spitting out jewels and jade, which turned into thousands of islands and islets in a bay in the northern part of the country, forming a formidable line of defense against the invaders. By magic, numerous rocks abruptly appeared in the sea, just ahead of the front line of the invaders’ ships, which struck the rocks, whereas the ships behind them had no time to stop and thus hit the wrecked ships of the front line.

In this way, the dragons saved the young Vietnamese nation, and for this reason, the bay was named Ha Long, meaning ‘descending dragons’.

“By magic, numerous rocks abruptly appeared in the sea, just ahead of the front line of the invaders’ ships.” – Islands, consisting of limestone rocks, created about 350 million years ago, Halong Bay. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Caves on the shore of a limestone island, created about 350 million years ago, Halong Bay. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Eroded limestone rock, Van Long Nature Reserve. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wales

Rocky area on the peak of Glyder Fawr, Snowdon National Park, Gwynedd. The standing stones are possibly a man-made structure. The highest mountain in Wales, Mount Snowdon (1085 m), is seen in the background. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

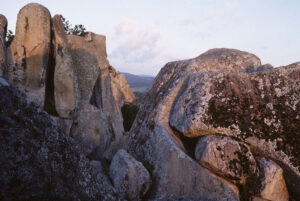

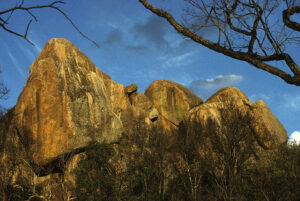

Zimbabwe

Construction of Great Zimbabwe, capital of the Kingdom of Zimbabwe, took place between the 11th and 15th Centuries A.D. It is believed that this stone city, which covers an area of 7.2 km2, was the residence of a local king. At its peak, it would have housed about 18,000 inhabitants.

Evening light on eroded rock formations around the Hill Ruins, Great Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Eroded rocks in evening light, Matobo National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Uploaded February 2020)

(Latest update April 2024)