Vanishing peoples of India

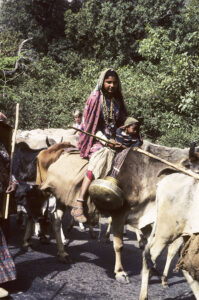

Shy Mali girls, Odisha. One of them has smeared yellow paste in her face, presumably to protect her skin from the fierce sunshine. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gujjar-Bakarwal with camels, laden with huge bundles of hay, Rajaji National Park, Uttarakhand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

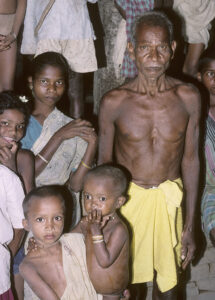

Gadaba girl with her grandfather, Odisha. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

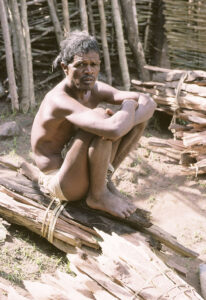

Sabara man, weaving a basket from bamboo strips, Odisha. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

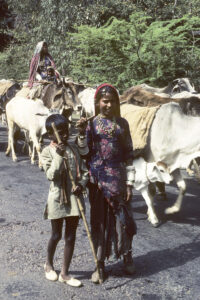

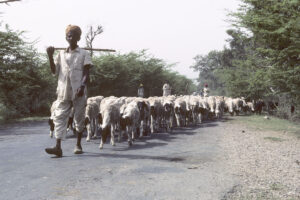

Rabari nomads, walking along a road with their animals, near Alwar, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Koya child, Odisha. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Aboriginals of India are mostly small people, many of Australoid descent, who have been living in the forests for thousands of years. When the Dravidians, and later the Aryans, invaded India, these tribal peoples were driven into remote areas.

Unfortunately, the culture and way of living of these peoples are rapidly disintegrating, and many have lost their land to entrepreneurs, who extract coal, iron and other minerals from it. Owners of paper factories have persuaded several of the tribes to plant eucalyptus trees on their land, promising these people a large outcome from these trees. However, they omit to inform them that eucalyptus trees dry out the soil, often leading to scarcity of water in areas, which were previously covered in lush forest.

In village schools, tribal children get acquainted with modern ways, and some have begun to despise their traditional way of life. Many half-grown boys drift to the cities, where they become unskilled labour. Today, poverty and alcoholism prevail in many tribal villages.

Many tribal people still live in the states of Odisha (Orissa), Chattisgarh, and Madhya Pradesh. As per 2001 census, the tribal population in Odisha alone was about 8 million, which constitutes around 22% of the total population of this state and almost 10% of the total tribal population in India.

The Indian Government has classified most of these peoples with the peculiar terms ‘scheduled caste’ and ‘scheduled tribe’. However, most Hindus regard them as dalit, ranging outside the Hindu caste system, and, as such, as a lower class of people.

This page also includes some nomadic peoples of Caucasian or Mongolian descent. The major part of the pictures below were taken in 1997, or prior, when many tribal peoples had still preserved part of their traditional ways, and some were practicing animist rituals. More about this issue is found on the page Religion: Animism.

Bhogta

This tribe, numbering around 260,000, live mainly in the state of Jharkhand, but also some in Bihar, West Bengal, and Odisha (Orissa). Officially, they are classified as a scheduled caste, but they themselves claim status as Kshatryas (the second highest caste). All are Hindus, but they also worship their ancestors and family deities. Brahmins perform their marriage rituals, which they will not do for any scheduled caste.

The Bhogtas were traditionally farmers, and they also produced rope and cots to sell. Today, many are day-labourers on tea plantations, others work in private and government services. (Source: joshuaproject.net)

These Bhogta tribals have been collecting firewood in the scrub forest around their village, near Bodhgaya, Bihar. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bhogta children in a village school, near Bodhgaya. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bhumia

The name of this tribe is derived from the word bhumi (‘soil’). According to their legends, they were the first people to start farming in the highlands of Koraput, and agriculture is still their main occupation. Their houses are rectangular in shape with gabled roofs. The walls are made either of wooden planks or wattle plastered with mud. The roof consists of bamboo or wooden rafters, thatched with a local grass named piri. They grow rice in the lower areas, gram, rape seed, and vegetables on higher ground. They also produce baskets, made of split bamboo, to sell in the local markets. (Source: kbk.nic.in/tribalprofile/Bhumia)

According to a 2011 census, their number is about 126,000. They worship various local deities, but also the Hindu god Shiva. Most of their festivals are connected with agriculture.

Bhumia village, near Jeypore, Odisha. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Changpa

A semi-nomadic people, living mainly in the Changthang region of Ladakh. It is believed that they originally migrated from Tibet in the 8th Century, and, until recently, a small number resided in the western part of Tibet. However, most of them were relocated due to establishment of the Changthang Nature Reserve.

For the major part of the year, the Changpa move across vast areas of the Tibetan plateau, where they graze their flocks of sheep and goats. They also raise yaks for meat, milk, and transportation, and horses for riding or carrying loads. Since the early 1970s, many have also been raising cows for milk production. Many of their goats produce the famous pashmina wool, which is one of the main sources of income for this people. In winter, they descend to lower areas.

Changpa are Mahayana Buddhists. This branch of Buddhism is presented in depth on the page Religion: Buddhism.

Changpa family, encountered on the Pulo Konka La Pass, Ladakh. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gadaba

This tribe, also called Gutob, number around 123,000, residing in Odisha, Telangana, and Andhra Pradesh. They live in villages, and a majority are farmers, practicing both slash-and-burn and plough cultivation. Others work as day-labourers.

In former times, Gadaba girls would wear two white metal neck rings, and as their head grew bigger, the rings could not be removed. Only after the death of the woman, a blacksmith would remove them. The women would also wear a traditional two-piece dress, often striped in red, blue, and white, woven by the women themselves.

This tribe performs a group dance, called dhemsa. The dancers form a chain by clutching each other at a shoulder and waist, moving to the tune of traditional instruments.

Since the early 1980s, many Gadabas have been displaced from their villages by the building of hydro-electric dams and the resulting lakes.

Gadaba tribals in a village near Jeypore, Odisha. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This old woman is wearing the traditional neck rings of the Gadaba. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

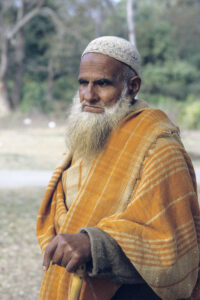

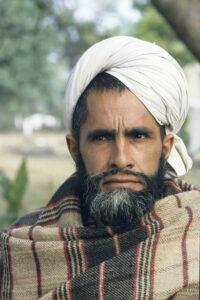

Gujjar-Bakarwal

This people of pastoral Muslim nomads live in the north-western part of the Indian Himalaya, in northern Pakistan, and in the Nuristan Province of north-eastern Afghanistan. They are mainly goatherders and shepherds, and some also have camels. The term bakarwal is Indo-Aryan, derived from bakara (‘goat’ or ‘sheep’) and wal (‘one who takes care of’).

In 1991, the Gujjar-Bakarwal were granted tribal status in Jammu and Kashmir by the Indian government.

Although the Rajaji area in Uttarakhand was declared a national park in 1993, the Gujjar-Bakarwal still live here. Foresters have pointed out that these people should be banned from grazing their animals in the park, but, ironically, they seem to benefit wildlife here, as they keep poachers away from the area. For instance, the number of wild Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) in the park has increased in later years. The Gujjar-Bakarwal themselves do not harm wildlife, as they are vegetarians.

However, the efforts of the foresters have been successful, and it seems that the Gujjar-Bakarwal have to be relocated. How that will effect the population of elephants and other animals remains to be seen.

Gujjar-Bakarwal men are bearded. – Rajaji National Park, Uttarakhand. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Camels, laden with huge bundles of hay, Rajaji National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Jani

The Jani are a sub-tribe of the Paraja tribe of Odisha (see below).

Jani village, near Kotpad, Odisha. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Jani woman, weaving a basket from bamboo strips. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Jani woman, cutting horse radishes. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Jani man is loading rice into baskets. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female Jani shaman, standing next to a sacred pole outside a shrine, dedicated to a local goddess, Mauli. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This picture shows clay images, which have been placed as offerings beneath a sacred tree outside the Mauli shrine. I was told that an offering of a clay tiger, for instance, would protect you against tigers, an offering of a clay cow would protect against disease among cattle, etc. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Khond

The Khonds are a designated scheduled tribe in the states of Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Jharkhand, and West Bengal. Traditionally, they are hunter-gatherers, and a few still practice this way of life. Today, the majority are farmers, practicing slash-and-burn agriculture. However, the introduction of education, medical facilities, irrigation, and establisment of plantations, have forced many into the modern way of life, and their traditional life style, customs, and values have changed drastically in later years.

Traditionally, these people were animists, but today almost all are Hindus. According to a 2011 census, they number around 1.6 million.

Khond village, near Rayagada, Odisha. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Khond beauties. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Koya

This people, numbering about 750,000, live in the states of Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Odisha. Today, they are mainly farmers and artisans, making bamboo furniture, mats for fencing, dust pans, and baskets. They grow various types of millet, vegetables, and edible tubers.

Many Koya have been displaced by development and hydro-electric projects, forcing them to work as day-labourers. The scarcity of such jobs has lead to malnutrition of children and instances of anemia in women.

The Koya practice marriage after maturity. In former days, the bride’s maternal uncle arranged the match, and marriages between cousins were common. A wealthy groom would have no problem finding a bride, but poor ones would often have to bribe the village headman to allow them to capture a bride. In the most simple wedding ceremony, the bride bent her head, and the groom would lean over her, while water was poured on their heads. Once the water had drained off the bride’s head, they were declared man and wife. They would then drink milk, eat rice, and walk around a mound of earth. After getting the blessings of the elders, they would go to their new home. (Source: The Castes and Tribes of Southern India. Nature 84 (2134): 365-367, September 1910)

Koya tribals, Odisha. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This elderly Koya woman is carrying embers on a piece of bark. She is wearing the traditional female dress of this tribe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Elderly Koya woman, weaving a basket from bamboo strips. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This young Koya is cutting his friend’s hair with a razor-blade. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Koya woman, pounding maize. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

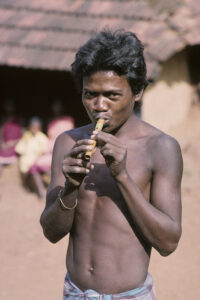

Mali

The Mali of Odisha are expert farmers and vegetable growers. However, vast changes have occurred in the form of schools, health centres, power plants, roads, etc., disrupting their traditional life style, values, and occupations.

Mali village, near Jeypore, Odisha. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mali people. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mali beauties. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This young Mali is playing on a flute. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mali man with sugarcane. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mali women, pounding tubers of Indian arrowroot (Curcuma caulina) to produce edible starch. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Maria

A scheduled tribe of the Bastar District in the state of Chhattisgarh. They grow lentils and vegetables, and liquor plays a key role in their society. They are famous for their mixed-sex dormitories, called ghotul, where young people experience premarital sex, sometimes with a single partner, sometimes several.

Maria villagers, Bastar District. Their grave countenance is caused by the fact that they had been deprived of their land and were suffering from malnourishment and disease. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Maria woman, carrying firewood. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Paraja

The Paraja claim that their ancestral home is in the Bastar area of today’s Chattisgarh, and that they migrated to Odisha several hundred years ago. Traditionally, they were hunter-gatherers, but today a majority are farmers, practicing slash-and-burn cultivation or crop rotation. Some also breed cattle, others are artisans, producing textiles, baskets, and tools.

The latest population census puts their number at around 350,000. Most are Hindus, a few are Christians.

Paraja tribals, bringing goods to a market in Tanginiguda, Odisha. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Parajas, Tanginiguda. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These young Paraja girls, their hair adorned with flowers, are selling peas at the market in Tanginiguda. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female Paraja vendors at a market in Kotpad. Note the tattoos on their arms. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Paraja tribals, performing a ceremony in their field. After a satisfactory harvest, they bring offerings of food to the Hindu Mother Goddess Durga, after which they eat a meal in the field. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rabari

The Rabari were nomads in the past, roaming the states of Gujarat, Rajasthan, and Punjab, as well as Sindh in Pakistan. However, they are now semi-nomads, returning to their village at a certain season to sell meat and milk. Many have abandoned the nomadic lifestyle for a modern life, settling down in cities. The majority are Hindus. The name Rabari means ‘outsider’, a fair description of their status within Indian society.

They claim to have been created by the mother goddess Parvati, consort of the mighty god Shiva. According to their legend, Parvati was cleaning dust and sweat from Shiva as he meditated, and from the dirt she moulded a camel. However, it kept running away, so Parvati created the first Rabari to tend it.

Rabari nomads, walking along a road with their animals, near Alwar, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sabara

This people, also known as Sora, mainly live in southern Odisha and northern Telangana. Their houses have mud walls and thatched grass roofs. They practice slash-and-burn cultivation, but are gradually taking up settled agriculture. Some still go hunting in the jungles. The men often wear only a loin cloth, whereas the women wear saris.

Some Sabara still retain their traditional tribal customs and traditions. Marriages are arranged by bride capture, elopement, or negotiations. Their religion is animism. “A shaman, usually a woman, serves as an intermediary between the living and the dead. During a trance, her soul is said to climb down terrifying precipices to the underworld, leaving her body for the dead to use as their vehicle for communication. One by one, the spirits speak through her mouth. Mourners crowd around the shaman, arguing vehemently with the dead, laughing at their jokes, or weeping at their accusations.” (Source: P. Vitebsky. Dialogues with the dead. Natural History Magazine, March 1997)

Sabara village, near the Sabari River, Odisha. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Drying crops. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Sabara woman scoops up crops which have been drying in the sun. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sabara family outside their home. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sabara men, weaving baskets from bamboo strips. The man in the lower picture is blind. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young Sabara mother with her infant son. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sabara children. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sabara boy, playing with a ring, made from woven strips of split bamboo. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Sabara boy, carrying an axe, is passing across a field of rapeseed. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sabara women, selling yoghurt and fruits. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sabara man, selling bundles of firewood. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Some Sabara still go hunting in the jungle. These men show bow and arrow, and a spear made from a bamboo stem. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Sabara demonstrates the usage of bow and arrow. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Toda

The Nilgiri Mountains constitute a part of the Western Ghats, a mountain range, which stretches most of the way along the west coast of India, from Goa south to the southern tip of the subcontinent. The highest point in the Nilgiris, Dodabetta, reaches a height of 2,637 m. The name Nilgiri is derived from the Tamil neelakurinji, the local name of a blue-flowered plant, Strobilanthes kunthiana, of the acanthus family (Acanthaceae), which only blooms at intervals of 12 years, but so profusely that entire mountain slopes become bluish. (Neela means ‘blue’ in Tamil). By the British, neelakurinji was corrupted to nilgiri, which means ’blue hill’ in Hindi, thus largely the same meaning.

In the 1800s, the Nilgiri Mountains were covered in lush monsoon forests. However, establisment of tea plantations by the British led to large-scale immigration by poor, landless people. Following the independence of India, exploitation of the forests expanded, and now large-scale planting of eucalyptus trees was carried out, to supply wood for a fiber factory. Eucalyptus seriously drains the soil, and today there is often scarcity of water in the formerly humid Nilgiri Mountains. The forest has shrunk alarmingly, almost exclusively conserved in nature reserves.

For the Todas, a Dravidian people, who had been living in these mountains for hundreds of years, the arrival of the strangers was fatal. Formerly, their culture and religion was centered around the water buffalo. They drank the milk, exchanging it with neighbouring tribes for crops, honey, metal items, and other necessities. The establishment of tea plantations, however, led to a catastrophic lack of grazing grounds, and the traditional life style of the Todas collapsed.

In the 1940s, their number had dwindled to a mere 600, partly due to the traditional killing of most newborn females to avoid overpopulation, partly due to diseases transmitted by the immigrants. Furthermore, childbirth traditionally took place in the jungle, where the woman was left alone to take care of herself. Many children died as a result, and some mothers were eaten by tigers.

A Toda woman, who had been educated as a nurse, made a huge effort to improve the health situation of the tribe, and with the blessing of the elders, the two above mentioned habits were abandoned.

Today, there are around 1,100 Todas, many of which have converted to Christianity. Some make a living by producing souvenirs for tourists.

Old Toda, Ooty, Tamil Nadu, 1976. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Toda women, Ooty, 1976. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Uploaded June 2021)