Sheep and goat

Grazing sheep and lambs, Hammerknuden, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mixed flock of goats and sheep, blocking a road, Col du Mt. Cenis, France. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gotland sheep, grazing towards evening on a November day, near Horsens, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Foggy morning with grazing sheep, Gourette, near Col d’Aubisque, Pyrenees. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Yummy! This cardboard box is really delicious!” – Izmir, Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mary had a little lamb,

Its fleece was white as snow,

And everywhere that Mary went

The lamb was sure to go.

He followed her to school one day,

That was against the rule.

It made the children laugh and play,

To see a lamb at school.

And so the teacher turned him out,

But still he lingered near,

And waited patiently about,

Till Mary did appear,

And then he ran to her, and laid

His head upon her arm,

As if he said: “I’m not afraid,

You’ll keep me from all harm.”

“What makes the lamb love Mary so?”

The eager children cry.

“O, Mary loves the lamb, you know,”

The teacher did reply,

“And you each gentle animal

In confidence may bind,

And make them follow at your call,

If you are always kind.”

Sarah Josepha Hale (1788-1879), American writer and editor.

Goats go past the back of the house,

Like dry leaves in the dawn,

And up the hill like a river, if you watch.

At dusk, they patter back like a bough

Being dragged on the ground,

Raising dust and acridity of goats,

And bleating.

Our old goat we tie up at night in the shed

At the back of the broken Greek tomb in the garden,

And when the herd goes by at dawn,

She begins to bleat for me to come down

And untie her.

From the poem She-Goat, by English poet and writer David Herbert Lawrence (1885-1930), written in Taormina, Sicily, during the 1920s.

In all editions of this poem, which I have been able to find on the internet, the poem reads, “Raising dusk and acridity of goats,” which must be a spelling mistake. How do you raise dusk? The talk must be about dust, so, humbly, I have allowed myself to correct the word.

Domestic sheep (Ovis aries)

“Counted the wool bundles this morning as they bounced through the narrow corral gate. About three hundred are missing, and as the shepherd could not go to seek them, I had to go. (…) until I found the outgoing trail of the wanderers. It led far up the ridge into an open place surrounded by a hedge-like growth of ceanothus* chaparal**. Carlo [a dog] knew what I was about, and eagerly followed the scent until we came up to them, huddled in a timid, silent bunch. They had evidently been here all night and all the forenoon, afraid to go out to feed. Having escaped restraint, they were, like some people we know of, afraid of their freedom, did not know what to do with it, and seemed glad to get back into the old familiar bondage.”

John Muir (1838-1914), Scottish-American writer and environmentalist, in his book My First Summer in the Sierra (1911). During his stay in the Sierra, Muir worked for Mr. Delaney, a sheep farmer.

* a genus of about 60 species of shrubs and small trees in the buckthorn family (Rhamnaceae).

** a community of shrubby plants, adapted to dry summers and moist winters, typical of southern California.

Sheep were among the first animals to be domesticated by humans, maybe as early as 11,000 to 9000 B.C., in Mesopotamia. The ancestor of the domestic sheep is still disputed, but today the most common hypothesis is that it is descended from the Asiatic mouflon (Ovis orientalis). Previously, it was assumed that it is descended from the European mouflon (O. musimon). However, today many authorities regard this species as an ancient breed of domestic sheep, which has turned feral.

A male sheep is called a ram, or tup, and a castrated ram is a wether. A female is called a ewe. This word is pronounced in various ways, often as ‘yo’ or ‘you’, in Scotland as ‘yow’ (rhyming on ‘how’). Young sheep are called lambs.

Initially, sheep were raised for meat, milk, and skins, the latter utilized for warmth in the fierce winters of the Middle East.

Woolly sheep emerged in Iran around 6000 B.C., and the earliest woven clothes known are from about 4000 to 3000 B.C. Over time, various cultures, including the Persians, relied on income from trading wool.

Not long after the domestication of sheep, they were brought to other parts of Asia, and around 6000 B.C. they were also brought to Egypt via the Sinai Peninsula. They were present in Europe from about the same time.

In America, the first sheep arrived with the second voyage of Columbus in 1493, and the first sheep were brought to Australia in 1788. By 1820, there were already about 100,000 on the Australian continent, and just ten years later a million. Today, the total population worldwide is estimated at one billion.

Today, the European mouflon (Ovis musimon) is regarded as an ancient breed of domestic sheep, which has turned feral. These pictures show a ram near Lake Rørbæk, central Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Portraits of sheep, resting in the shade beneath an old oak, central Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Over the years, numerous breeds of sheep have evolved. These pictures show two breeds: Oxford Down with lambs (top), and Gotland sheep, photographed on a cold winter morning, their breath forming steam. – Both pictures are from Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grazing ram on Conic Hill (385 m), Loch Lomond, Scotland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Until the late 1900s, a small part of the inhabitants of Iran were semi-nomadic herders, who spent the winter with their sheep and goats on the grass steppes in south-western Iran. In spring, they would drive their animals up into the Zagros Mountains, and when an area had been utilized for grazing, they would continue nortwards, until the harsh autumn weather forced them to move south again.

During a stay in the Zagros Mountains in 1973, my companion Arne Koch Christoffersen and I paid a visit to a nomads’ camp. The following 5 pictures were taken during this visit, which is related on the page Travel episodes – Iran 1973: In the mountains of Luristan.

Grazing sheep, Luristan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Herding boy with his sheep. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

At night, and in bad weather, lambs and kids were kept in enclosures inside this nomad’s tent, mainly to protect them from wolves. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On a spring day, these nomads have loaded their tents and other belonging on donkeys, moving to a more northerly grazing area in the Zagros Mountains. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Resting sheep and goats, Plateau Presa de las Niñas, Gran Canaria. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young sheep herders, Thar Desert, Rajasthan, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Assisted by dogs, this woman is driving home a large flock of sheep along the road, Col de la Madelaine, Pyrenees. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female sheep herder, Tirebolu, northern Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A live road-block. – Numerous sheep block the passage of a bus on a high-altitude gravel road in Lahaul, Himachal Pradesh, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

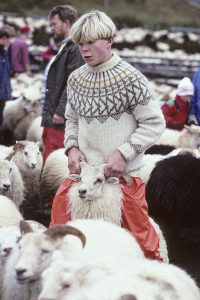

In Iceland, sheep spend the entire summer on grazing grounds in the mountains. In September, when winter is approaching, they are rounded up, after which they are divided according to owners, using different ear-cuts as a means of identification. Each owner then takes his sheep back to the farm on trucks.

The pictures below were taken at Fnjóská, near Akureyri.

(Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Shearing a Gotland sheep with an electric trimmer, a so-called handpiece, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Carding wool to make yarn, Melstedgård Agricultural Museum, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dyed woollen yarn, Melstedgård Agricultural Museum. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The role of sheep in culture and mythology

Domestic sheep were present in Egypt from about 6000 B.C. To the Ancient Egyptians, a ram-headed sphinx was the symbol of the god Amun, who, during the 11th Dynasty (21st Century B.C.), was the patron deity of Thebes. Later, he became an important national god, being fused with the Sun God, Ra, to become Amun-Ra.

Ram-headed sphinx, photographed at the Great Temple of Amun, Karnak, Luxor. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fat-tailed sheep on a frieze, Sultanahmet, Istanbul, Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

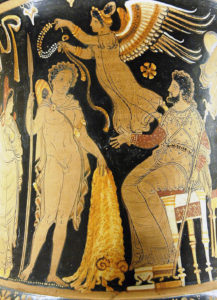

A famous sheep skin plays an important role in the Greek epic Jason and the Golden Fleece, from at least the 8th Century B.C., in which Jason and his Argonauts set out on a quest, by order of his uncle, King Pelias, who had usurped the throne in the city of Iolcos, in Aeolia, from his half-brother, Jason’s father.

When Jason grows up, he travels to Iolcos to demand the throne, but is ordered first to obtain the fleece of a golden-haired, winged ram, which is kept in the land of Colchis (on the Black Sea coast, in present-day Georgia), guarded by a terrible dragon. This fleece is a symbol of royal authority, and in case Jason and his men should succeed in acquiring the fleece and bring it to him, Pelias believes that he will remain on the throne.

The quest of Jason and his men is successful, and back in Iolcos, he presents King Pelias with the Golden Fleece. Later, however, he kills him and takes over the throne.

Jason presents King Pelias with the Golden Fleece, and Nike, the Winged Goddess of Victory, prepares to crown him with a wreath. – Apulian vase, c. 340 B.C., exhibited in Louvre. (Photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen, public domain)

Domestic goat (Capra aegagrus ssp. hircus)

The goat is also among the earliest domesticated animals. About 8000 B.C., inhabitants of the Zagros Mountains in south-western Iran began domesticating the local wild goat, the Bezoar goat (Capra aegagrus). These Stone Age people were herding goats for their meat and milk, the pelt was used as clothing, tools were made from the bones, and the dung was used as fuel.

The domestic goat is still closely related to the Bezoar goat, which is named ssp. aegagrus, to distinguish it from the domestic goat, ssp. hircus.

A male goat is called a billy, or a buck, whereas a castrated male is a wether (like a castrated sheep). A female goat is a nanny or a doe. Young goats are called kids.

Over time, goats, similar to sheep, have been spread to most areas of the globe. Its total worldwide population is estimated at one billion, about half of which are in Asia.

It is almost unbelievable, what goats are able to digest – bone-dry grass, thorny twigs, cardboard boxes. Indeed, in northern India, I once watched a herd of goat head straight for a growth of very poisonous thorn-apples (Datura stramonium) and commence eating the fruits. Apparently, goat stomachs can neutralize the toxins.

Goats, grazing in an alpine meadow, Puga Marshes, Ladakh, India. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The domestic goat has evolved into numerous breeds. These pictures show a flock of Wallis goats, resting on a rocky outcrop on the island of Bornholm, Denmark. This Swiss breed has black foreparts and white hind parts. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

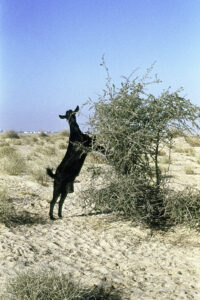

Goats are very agile. Standing on their hindlegs, these two are feeding on bushes in the Thar Desert, Rajasthan, India (top), and in Kuwait. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grazing goats in a desert near Lake Tso Moriri, Ladakh, India (top), and in a grassland south of Dolo Mena, Ethiopia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These men are driving a mixed flock of goats and sheep along a road, Kielang, Himachal Pradesh, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Goats, resting on a ruined bridge, near Izmir, Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This goat in the city of Jaisalmer, Rajasthan, India, is investigating provisions on a loaded camel in search of food, but is chased away by the camel. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

From a window, this goat is watching the world go by, Dhulikhel, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Goat, searching for food in a garbage container, Kochi, Kerala, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Resting kids, Tamur Valley, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Goats are mostly kept for their meat and milk. In this picture, dried goat carcasses are for sale at a market in the town of Shigatse, Tibet. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Hindu festival of Bisket Jatra is celebrated with vigour by the Newar population of the city of Bhaktapur, Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. During this festival, several gods are worshipped, notably Kalo Bhairab, a local form of the supreme god Shiva.

These Newars in Bhaktapur have sacrificed a goat to Kalo Bhairab. They have just applied oil to the head of the goat and ignited it. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kali is a Hindu goddess, a bloodthirsty form of Devi, the shakti (female energy) of Shiva. In temples, dedicated to Kali, daily offerings of blood are made. The various forms of Devi are described on the page Religion: Hinduism.

Newar people, waiting in line with their offerings outside a Kali temple at Dakshinkali, Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. The commotion is caused by the goat, which has just left pellets on the feet of a woman. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Heavy impact on the environment

In many countries, sheep and goats have a heavy impact on the environment, often seriously overgrazing areas, as their numbers are often far too high for the vegetation to sustain them. Such areas include most countries around the Mediterranean and in the Middle East, and also Tibet, the Himalaya, and the Andes.

On numerous small islands around the globe, goats have often escaped (or have been released on purpose), forming feral populations, which create havoc through overgrazing. These islands are mostly without larger predators, meaning that the goats have no natural enemies here. Measures have been taken to rid many of these islands of their goats.

Huge mixed flocks of sheep and goats on overgrazed slopes, Bara Lacha Pass, Lahaul, Himachal Pradesh (top), and near Sarchu, Ladakh, both in north-western India. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Goats, grazing in a desert, Jhong River Valley, Mustang, central Nepal. The only vegetation, which has been left by the goats, consists of extremely spiny bushes and toxic plants. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Uploaded September 2017)

(Latest update April 2024)