Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Tanzania 1989: Memorable nights in the Ngorongoro Crater

Once we reach the park, we observe many giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis) grazing on the grass-covered mountain slopes. Their pattern is quite unique, and some authorities consider them a hybrid between reticulated giraffe, subspecies reticulata, and Masai giraffe, subspecies tippelskirchi. They are sometimes called Galana giraffes.

Our camp is situated at a beautiful spot in the foothills of Mount Meru, beneath a few large trees, which are enveloped by strangler figs (Ficus). The area around our camp is an important feeding area for animals like giraffe, bushbuck (Tragelaphus scriptus), warthog (Phacochoerus africanus), and a tiny antelope, a subspecies of Kirk’s dik-dik (Madoqua kirkii ssp. cavendishi).

Birdlife is abundant, including Hartlaub’s turaco (Tauraco hartlaubi), paradise flycatcher (Terpsiphone viridis), and, along streams, mountain wagtail (Motacilla clara) – a habitat quite similar to that of the Eurasian grey wagtail (M. cinerea). A young crowned eagle (Stephanoaetus coronatus) is calling from a tree.

During our first night here, we are a little alarmed by an unbelievably powerful noise from the trees above our tents, sounding like a mixture of some gigantic croaking frog, and a car engine that won’t start. As it turns out, the source of this sound is a troop of Kilimanjaro black-and-white colobus monkeys (Colobus guereza ssp. caudatus), which live in the trees around our camp.

The montane rainforest is very beautiful, with many large trees, their trunks covered in mosses, whereas their branches are festooned with old man’s beard lichens (Usnea). (A fascinating account of these lichens is related on the page Quotes on Nature.) High above the forest, two mountain buzzards (Buteo oreophilus) are soaring.

Various bushes grow in the understorey, including tree heath (Erica arborea) and a shrubby species of St. John’s wort, Hypericum revolutum, and herbs include a species of balsam (probably Impatiens pseudoviola), and orange trumpet vine (Thunbergia gregorii), a close relative of the well-known Black-eyed Susan (T. alata), which is described on the page In praise of the colour yellow.

Soon the road comes to an end. Although dark, threatening clouds are looming on the horizon, my companions commence their walk. Shortly after their departure, rain starts pouring, continuing almost incessantly throughout the day.

After pitching our tents at a primitive campsite near the river, we commence on a game drive to experience the rich wildlife of the park. On the savanna, large herds of impalas (Aepyceros melampus) and Grant’s gazelles (Nanger granti) are grazing, accompanied by a troop of about a hundred olive baboons (Papio anubis).

Two barn owls (Tyto alba) are sitting in a huge baobab, using the tree as a day roost. A strong musk scent drifts out from the interior of the hollow baobab, indicating that bats spend the day here. Several spikes are hammered into the trunk, all the way up, placed here by honey gatherers, says Moses.

Early in the afternoon, a tremendous rain storm passes over. The rain is so powerful that the landscape is barely visible through the dense mist. Just before sunset, the rain ceases, and in the west, the sky turns red and yellow.

Back at our camp, we are met by a pitiful sight: Lars’s tent and mine are flattened, and everything inside is drenched: sleeping bags, sheets, clothes. Thomas’s and Conny’s tent is simply missing, washed away, and they find it about 50 m from the camp.

Luckily, before leaving, they had the foresight to empty their tent, and they are kind enough to lend me a spare sleeping bag, while Lars spends an uncomfortable night on the front seat of the car, which is alive with bed bugs. He hardly gets any sleep at all.

The following morning is bright and sunny, and we spend some hours drying our equipment.

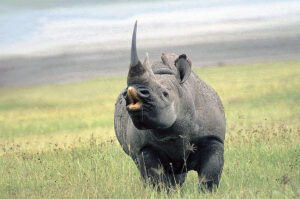

Today, this caldera is one of Africa’s best wildlife areas, home to large numbers of animals, including white-bearded wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus ssp. mearnsi), plains zebra (Equus quagga ssp. boehmi), lion (Panthera leo), spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta), African buffalo (Syncerus caffer), black rhino (Diceros bicornis), and hippo (Hippopotamus amphibius).

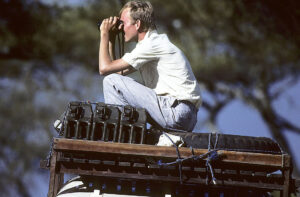

We observe two zebra stallions engaged in a dominance dispute, neighing loudly and galloping side by side, while they bite each other’s legs and do their best to bite at the opponent’s testicles. A bull rhino sniffs a tuft of grass, into which a female has urinated, baring his lips in a posture, called flehmen. The inhaled air passes special sensing organs that are able to detect whether the female is in heat. This behaviour is seen in many mammals, including cats and horses.

Birdlife is abundant in the crater. In a salt-lake, thousands of lesser flamingos (Phoeniconaias minor) are feeding, besides many species of waders. In grassy areas, large kori bustards (Otis kori) and Masai ostriches (Struthio camelus ssp. massaicus) strut about.

During a slight rain shower, a male black-bellied bustard (Lissotis melanogaster) is displaying, bending his long neck and filling it with air, while emitting a humming sound. He then stretches his neck as far into the sky as possible, ending the whole séance with a loud ‘pop’.

From other tourists, camping nearby, we learn that during our absence they saw a troop of green vervets (Chlorocebus pygerythrus), jumping up and down on our tents. These monkeys are incredibly naughty. As soon as you turn your back on them, they steal fruit or other food items. But we can hardly believe that these small monkeys would be able to create such havoc. Maybe the tents have been destroyed by baboons.

Lars, Thomas, and Conny now spend quite some time repairing their tents, while I clean my sleeping bag. My tent is beyond repair, so I hand Lars one of my tent poles, which, luckily, can replace his broken one. As I am now without a home, Lars generously suggests that I sleep in his tent, which has plenty of space for two people.

The following evening, as we are just about to take our seats on the rim of a concrete fireplace to enjoy our meal, Moses suddenly exclaims: ”Careful, there are lions around!”

When we switch on our torches, we observe three lionesses, less than 10 m away, so we quickly retreat to a respectful distance. The lions, however, are not interested in us, but in a puddle of water, which has gathered beneath a leaking tap. When they have quenched their thirst, they disappear into the darkness.

In the night, I am awoken by Lars, who shakes my shoulder, whispering: ”There are elephants just outside our tent, breaking branches off trees! What are we going to do?”

Loud creaking and crashing sounds can be heard, besides a crunch-crunch, when their strong teeth crush branches and twigs. The huge animals are so close that we can also hear their stomachs rumbling. All we can do is to stay as quiet as mice.

Thomas, in the other tent, is curious to see, what’s going on, so he starts unzipping the tent. Moses, who is spending the night in our car, shouts: ”Thomas, stay in your tent!”

The elephants, however, have heard the noise from the zipper and are now on their way towards the other tent to investigate. Moses yells, flashing the headlights of the car and starting the engine. The elephants get confused and retreat a short distance. They remain in the area for a couple of nerve-shattering hours, but finally we manage to fall asleep again, awaking at dawn, unharmed.

Zebras, wildebeest, Grant’s gazelles, kongonis (Alcelaphus cokei), and Defassa waterbuck (Kobus defassa) are grazing nearby, and in the trees around our camp site, tree hyraxes (Dendrohyrax arboreus) emit piercing screams. They look somewhat like fat rabbits with sharp fangs, but, in fact, their nearest living relatives are elephants!

In order to dry my laundry, I want to tie a clothes-line to a tree branch, but, as it turns out, the tree is occupied by a huge male baboon, who bares his formidable canines, assuming a threatening position.

”On your guard, you weakling!” he seems to say. I hastily retreat, finding another tree for my clothes-line!

The large fig tree near our camp is full of ripe fruits, which are much praised by various birds, including African green pigeon (Treron calvus), red-eyed dove (Streptopelia semitorquata), violet-backed starling (Cinnyricinclus leucogaster), and superb starling (Lamprotornis superbus). The latter is also observed bathing in a small puddle together with other birds, including the endemic rufous-tailed weaver (Histurgops ruficauda).

In the bushes above the lions, many wattled starlings (Creatophora cinerea) have built their nests – large heaps of sticks, with an entrance hole on the side. Most of the nests contain young of different age groups, and several tawny eagles (Aquila rapax) are sitting on top of the nests, scanning the surroundings for inexperienced young, which have just left the nest.

At Ndutu, we pay a visit to a luxurious lodge, hoping to supplement our rather monotonous diet with a delicious meal. Learning that a meal will cost 1900 Tanzanian Shillings, we make an orderly retreat, instead heading for the camp ground, where we cook our own meal – monotonous or not!

The following morning, the savanna west of Ndutu is indeed a wonderful sight: sunshine behind us, and pitch-black rain clouds in the western sky. It is time for Serengeti’s famous annual wildebeest migration. The savanna is completely covered in dense masses of wildebeest, as far as you can see, many of the dark-grey wildebeest cows followed by a pale-brown calf.

For an hour or more, we are parked near a small stream, where myriads of wildebeest are running down the bank, causing huge clouds of dust to rise – yet another great sight!

Kopjes are isolated rocky outcrops, which, somewhat wantonly, pierce the savanna here and there. Incidentally, they are the remains of ancient, eroded mountains. To the Boer, when they migrated to Southern Africa in the 1700s, these outcrops resembled heads, so they named them kopjes (‘head’ in Dutch).

When a spotted hyena enters the territory of the hunting dogs, two of the dogs immediately give chase. The hyena utters its peculiar laughing call, leaving the area at full speed. But it’s far too slow, compared to the swift dogs. After a few seconds, they catch up with the hyena, biting its hind legs a couple of times. The hyena screams, whirling around to snap at the dogs with its powerful jaws. The incredibly fast dogs swarm around the hyena, biting its behind and jumping backwards, before it is able to bite them.

The poor hyena zooms across the savanna, bleeding from its legs and behind, still chased by the furious dogs. Finally, it backs into a hole, where only its head and front paws are exposed. Here the dogs are unable to bite the hyena, as its powerful jaws keep them at bay. After a few minutes, the dogs return to their territory. Two other hyenas, which receive the same punishment, quickly retreat.

Hyenas are much attracted to hunting dogs, their favorite food being the dogs’ faeces, which they are willing to do almost anything to get at. There have been instances of hyenas, creeping up to a sleeping hunting dog to lick its anus – afterwards being bitten in their own behind. Hyenas often try to steal the prey of hunting dogs, and if their pack is large enough, they often succeed in chasing the dogs away from their prey.

The dogs are incredibly fast. In a moment, they have caught up with the gazelles, picking out a potential prey. Two dogs are chasing a buck, while the other two run some distance behind them, ready to prevent the buck from turning back. When gazelles get tired, they often begin running in semi-circles, in which case the dogs at the rear quickly take over the chase.

This hunt ends abruptly after only two minutes, when one of the dogs collides with the buck. The collision is so powerful that the buck makes a somersault, and a few seconds later the dogs have a firm grip at it. Their sharp teeth tear up the belly of the gazelle, and they start eating its intestines, while it is still alive.

This is a rather nasty sight, and for this reason, in the past, many hunting dogs were shot on sight by people, who hated this behaviour.

But in reality, this way of killing is fast and efficient. Large and deep wounds cause an instant shock effect, and the sufferings of the prey are probably rather limited, before it dies, which mostly happens within a few minutes. Larger prey like zebras and wildebeest live a little longer – up to 17 minutes has been recorded, but such cases are very rare.

People seem to have a much more sympathetic attitude towards the way large cats kill their prey, namely by biting it around the neck until it is strangled. This is not a very bloody affair, which is probably why people regard it as more ’humane’. In reality, the prey is suffering for a much longer time from being strangled than from being torn apart alive.

After finishing their meal, the dogs trot across the savanna towards their territory, and we decide to follow a bitch with swollen teats. She doesn’t mind the car at all, but approaches a den, emitting a strange, bird-like twitter.

Immediately, nine pups, about four weeks old, with black, wrinkled faces and enormous ears, emerge from the den. On their short legs, they totter towards the bitch, licking the corners of her mouth. She retreats a bit, makes a few convulsive throat movements, and then regurgitates a large portion of meat. The pups immediately fall upon it, swallowing the smaller bits and fighting over the larger ones. Sometimes it evolves into a tug-of-war, in which two pups haul at either end.

When the other three dogs return to the den, they also regurgitate meat, not only for the pups, but also for the mother and for the fifth dog, which remained back at the den to guard the pups. All dogs in a pack participate in rearing a litter. When the pups are young, the mother, and often also another dog, will remain at the den, while the other members of the pack go hunting.

Even if the mother dies, the other members of the pack will rear the pups. There has even been an example of a pack of male dogs rearing a litter, when the mother, which was the only female in the pack, had died.

You may read more about these fascinating dogs on the page Animals – Mammals: Hunting dogs – nomads of the savanna.