Birds in Africa

Tawny eagle (Aquila rapax), swallowing a leg of a hare, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lesser pied kingfisher (Ceryle rudis), perched on a dead acacia branch, Lake Baringo, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male white-bellied bustard (Eupodotis senegalensis) in evening light, Meru National Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male village weaver (Ploceus cucullatus), building a nest, Lake Bogoria, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In the period 1980-2003, I made altogether 8 prolonged visits, and 3 shorter ones, to Africa. Adventures during these visits are described on the Travel episodes pages, see Africa 1980-81, Zaire 1981, Tanzania 1988, Tanzania 1989, Tanzania 1990, Zambia 1993, and Ethiopia 1996. Other aspects of my stay in Zambia 1993, and a visit to Namibia 1993, are described on the page Countries and places. During these visits, I have managed to photograph a large number of bird species.

In 1988-1993, I participated in four expeditions to Tanzania, the aim of which was to count wintering waders, and to investigate bird life in coastal forests. In the forests, we caught birds in mistnets, and the major part of the portraits below stem from this work.

Families, genera, and species are presented in alphabetical order. The text is largely based on the websites ebird.org and Wikipedia, the etymology most often on J.A. Jobling 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names, Christopher Helm, London. Nomenclature largely follows the IOC World Bird List (worldbirdnames.org).

I have used the former name Zaire for the country today officially known as The Democratic Republic of Congo, as I find that name somewhat laborious. Furthermore, you can hardly place the term ‘democratic’ on a country that, for decades, has been pervaded by a chaos of violence.

Accipitridae Hawks, eagles, and allies

A huge family, comprising about 66 genera and c. 250 species of small to large raptors, distributed worldwide, with the exception of Antarctica.

Accipiter Sparrowhawks, goshawks

Comprising 51 species, this is the largest genus in the family. In Europe, these birds are known as sparrowhawks (smaller species) or goshawks (larger species), in America simply as hawks.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for hawk, derived from accipere (‘to grasp’), naturally alluding to the sharp talons.

Accipiter minullus Little sparrowhawk

The smallest species of the genus, with a length of only 23-27 cm, males weighing 75-85 g, females usually a little more, up to 105 g. Its size is reflected in the specific name, from the Latin minulus (‘very small’), diminutive of minus (‘less’).

It occurs in eastern and southern Africa, from Ethiopia and Angola southwards, living in various types of forest, including patches of woodland and scrub, typically along river valleys, sometimes even in suburban gardens.

A male African little sparrowhawk, Accipiter minullus, caught in a mistnet to be ringed, Msumbugwe Forest, northern Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Aquila True eagles

A genus of 11 species, found in most parts of the world, except the polar regions, South America, and rainforest areas. The generic name is the classical Latin word for eagle, perhaps derived from aquilus (‘dark in colour’).

Aquila rapax Tawny eagle

Divided into 3 subspecies, this eagle is breeding in the major part of sub-Saharan Africa, in the Indian Subcontinent, and in scattered locations in north-western Africa, south-western Arabia, and Iran. The plumage is highly variable, with distinct pale and dark morphs, and various intermediate forms.

The specific name is derived from the Latin rapere (‘to seize’).

Tawny eagle, pale morph, looking for fledged young in a nesting colony of wattled starling (Creatophora cinerea), Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tawny eagle, dark morph, Lake Manyara National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Intermediate morph tawny eagles, squabbling over a leg of a hare, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Aquila verreauxii Verreaux’s eagle

This striking eagle lives in hilly regions in eastern and southern Africa, the Chad area, and in the south-western part of the Arabian Peninsula. It is a very specialized species, feeding mainly on rock hyraxes (Procavia).

The specific name commemorates French naturalist Jules Verreaux (1807-1873), who visited southern Africa in the late 1820s. He collected the type specimen there.

Verreaux’s eagle with nesting material, Lake Manyara National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Buteo Buzzards

A genus of about 28 species, distributed on all continents, except Australia and Antarctica. In the Old World, these birds are known as buzzards, whereas the term hawk is often used in North America.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of the common buzzard (B. buteo). The English name is derived from Old French busard, which is a corruption of the classical Latin name.

Buteo augur Augur buzzard

Most adult birds are very distinct, with white underside, blackish back, and orange-red tail. However, the plumage varies, and a dark morph also exists. Young birds are brownish. This is mainly a species of highland grasslands, usually above an elevation of 2,000 m, occasionally observed up to 5,000 m. It is distributed from Ethiopia southwards through eastern Africa to Zimbabwe, with separate populations in western Angola and Namibia.

An augur was a priest in Ancient Rome, whose main role was to interprete the will of the gods by studying the flight of birds – whether they were flying in groups or alone, what kind of noise they made, the direction of flight, and what kind of birds they were. The observation of eagles, hawks, and owls was particularly significant. Why the name was applied to this particular species is not clear.

Augur buzzard, Ngorongoro Conservation Area, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Augur buzzard, taking off, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Augur buzzard, Sanetti Plateau, Bale Mountains, Ethiopia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Buteo oreophilus Mountain buzzard

As its name implies, this bird occurs in mountains. Its main habitat is forest, but it may also be observed in plantations. It is confined to eastern Africa, found in Ethiopia, South Sudan, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, eastern Zaire, Tanzania, and Malawi.

The specific name is derived from the Greek oros (‘mountain’) and philos (‘loving’).

Mountain buzzard, Shume-Magamba, Usambara Mountains, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Circaetus Snake-eagles

As their name implies, these birds feed mainly on snakes. There are 7 species, all restricted to Africa with the exception of the short-toed snake-eagle (C. gallicus), which breeds in southern Europe, western Asia, and the Indian Subcontinent.

The generic name is derived from the Greek kirkos, a type of hawk, in this connection associated with harriers (Circus); and aetos (‘eagle’).

Circaetus cinereus Brown snake-eagle

When sitting, this bird appears a uniform brown, but in flight it shows mainly white wings with black tips. It is widespread south of the Sahara, chiefly in open habitats, avoiding rainforest and desert areas.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘ash-grey’, from cinis (‘ashes’) – not a good name for this mainly brown bird.

Brown snake-eagle, Tarangire National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Circaetus fasciolatus Southern banded snake-eagle

This bird has a rather limited distribution, occurring mainly in evergreen coastal forests, from Kenya southwards to north-eastern South Africa.

The specific name is Latin, derived from fasciola (‘little band’), ultimately from fascia (‘band’), thus ‘the one with little bands’, alluding to the narrow bands on the lower breast and belly.

Southern banded snake-eagle, Mtama, southern Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Elanus Small kites

Members of this genus, comprising 4 quite similar species of small white, grey, and black raptors, are distributed throughout almost the entire globe, although they avoid colder areas.

The generic name is a Latinized form of elanos, the Ancient Greek word for kite.

Elanus caeruleus Black-winged Kite

This bird has a very wide distribution, found in all of sub-Saharan Africa, in north-western Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, France, the Nile Valley of Egypt, at several locations throughout the Middle East, from the entire Indian Subcontinent eastwards to southern China and Taiwan, and thence southwards through Indochina and the Philippines to Indonesia and New Guinea.

The specific name is derived from the Latin caelum (‘sky’), and a diminutive suffix, thus ‘small sky’, i.e. having the colour of the sky, thus ‘sky-blue’, alluding to the bluish sheen in the plumage.

Adult black-winged kite in evening light, Meru National Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young black-winged kites, one calling, West Coast National Park, South Africa. Immature birds may be identified by the scaly pattern on the wings. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gypohierax angolensis Palm-nut vulture

This vulture, the only member of the genus, lives along coasts, from Senegal southwards to Angola, and from Kenya southwards to north-eastern South Africa, and it may also sometimes be encountered along rivers inland.

This species is unique among vultures, as it feeds mainly on the fleshy husks of fruits of palms of the genera Elaeis and Raffia, which constitute more than 60% of the diet of adult birds and over 90% of the diet of juveniles. It also feeds on crabs, molluscs, frogs, fish, locusts, small mammals, and reptiles’ eggs and hatchlings, and it will occasionally attack domestic poultry, or feed on carrion.

The generic name is derived from the Greek gyps (‘vulture’) and hierax (‘hawk’).

Palm-nut vulture, resting in a mangrove tree, Mbezi River, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gyps Griffon vultures

A genus of 8 species of carrion-eating raptors, distributed in Europe, Asia, and Africa. The generic name is the Ancient Greek term for vulture.

The African species have decreased dramatically in numbers in recent years. Both species below have declined by over 90%, especially in West Africa, and they are now regarded as critically endangered.

Vultures in the Indian Subcontinent have also diminished alarmingly since the 1980s. More about this issue is found on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in the Indian Subcontinent.

Gyps africanus White-backed vulture

This vulture was once widespread and common in sub-Saharan Africa, occurring from the Sahel zone eastwards to Ethiopia and Somalia, and thence southwards through eastern Africa to South Africa and Namibia. Sadly, this species is now undergoing a rapid decline. The global population has been estimated at 270,000 individuals.

Previously, it was thought to be conspecific with the Asian white-rumped vulture (G. bengalensis), but today most authorities regard them as separate species.

White-backed vultures, feeding on a dead donkey, Palapye, Botswana. One bird has finished its meal and is now drying its wings. Two pied crows (Corvus albus) are also interested in the carcass. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

White-backed vulture at a carcass, Nairobi National Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gyps rueppelli Rüppell’s vulture

This species occurs throughout the Sahel region, and also in eastern Africa southwards to Mozambique. Formerly abundant, it may now count less than 20,000 individuals.

It was named in honour of German naturalist and explorer Wilhelm Peter Eduard Simon Rüppell (1794-1884), who collected numerous specimens of plants and animals in Africa.

Ruppell’s vultures and two white-backed vultures (centre), resting in a dead tree, Tarangire National Park, Tanzania. A dark rain cloud is looming on the horizon. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rüppell’s vultures and white-backed vultures, gathered around a pregnant plains zebra (Equus quagga ssp. boehmi), which has just been struck and killed by lightning, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rüppell’s vulture, feeding on the carcass of a white-bearded wildebeest calf (Connochaetes taurinus ssp. mearnsi), which was probably killed by lions, Serengeti National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Rüppell’s vulture, which was feeding on the remains of a white-bearded wildebeest calf, defends its meal against an intruding lappet-faced vulture (Torgos tracheliotos), Serengeti National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Preening Rüppell’s vultures, Serengeti National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Haliaeetus Sea-eagles, fish-eagle

A genus of 10 species, widely distributed in Africa and Eurasia, with a single species in North America.

The generic name is derived from the Greek hali– (‘of the sea’) and aetos (‘eagle’). Despite the name ‘sea-eagle’, many of the species are living at freshwater areas inland. These species are termed ‘fish-eagles’.

Haliaeetus vocifer African fish-eagle

This iconic bird is widely distributed in sub-Saharan Africa, always near water. It has been declining in later years, probably due to widespread usage of pesticides.

It was described by French naturalist François Levaillant (1753-1824), who named it vocifer (’the one who has a penetrating voice’) – a most suitable name for this eagle, whose scream is often resounding over the African landscape. It is the national bird of no less than three countries: Zambia, Zimbabwe, and South Sudan.

African fish-eagle, resting on a rock, Adamson’s Falls, Tana River, Meru National Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is resting in a Casuarina tree, Kisigese, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This bird, observed at the Rufiji River, Tanzania, was indeed confiding. Our rubber dinghy bumped into the tree, in which it was resting, but it merely glanced down at us and didn’t take off. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Soaring African fish-eagle, Lake Manyara National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This African fish-eagle has just caught a fish, Chembe, Lake Malawi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young bird, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lophaetus occipitalis Long-crested eagle

This medium-sized eagle, with its striking, bushy crest, is fairly common south of the Sahara, from Senegal eastwards to Ethiopia, and thence southwards to South Africa and Namibia. It mainly lives at forest edges and in moist woodlands, but may be observed in many types of open land, including grasslands, marshes, farmland, and plantations, from sea level up to about 2,000 m, occasionally higher.

At present, this bird is placed in the monotypic genus Lophaetus, but genetic research indicates that it is closely related to the spotted eagles, genus Clanga.

The generic name is derived from the Greek lophos (‘crest’) and aetos (‘eagle’). The specific name is from the Latin occipitium (‘the back of the head’), alluding to the position of the crest.

Long-crested eagle, perched on a dead tree, Arba Minch, Ethiopia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The crest of the long-crested eagle is rather grotesque. – Lake Manyara National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The characteristic silhouette of the long-crested eagle, Lake Manyara National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Melierax Chanting goshawks

This genus consists of 3 very similar, medium-sized raptors, distributed in the major part of Africa.

The generic name is derived from the Greek melos (‘song’) and hierax (‘hawk’), alluding to their melodious piping call.

Melierax poliopterus Eastern chanting goshawk

A bird of semi-desert, dry bushland, and wooded grassland, found from Eritrea southwards to central Tanzania, westwards to South Sudan and Uganda. When sitting, it can be separated from the similar dark chanting goshawk (M. metabates) by its yellow and black bill (versus red and black), and in flight by its white rump (versus barred in dark chanting goshawk).

The specific name is from the Greek polios (‘grey’) and pteros (‘wing’).

Formerly, southern African birds were included in this species, but have now been split to form a separate species, the pale chanting goshawk (M. canorus).

Eastern chanting goshawk, Yabello, southern Ethiopia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Eastern chanting goshawk, Meru National Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Micronisus gabar Gabar goshawk

This small raptor, the only member of the genus, is widely distributed south of the Sahara, avoiding rainforest and the Somali Desert. It also occurs in Yemen. It resembles a small chanting goshawk and was previously placed in the same genus.

The generic name is derived from the Greek mikros (‘small’) and nisus, the specific name of the common sparrowhawk, ultimately from the Greek nisos.

In Greek mythology, Nisos was a king of Megara, who possessed a purple lock of hair, which would protect him and his kingdom. According to one version of the legend, when King Minos of Crete besieged Megara, he tempted Nisos’s daughter Scylla with a golden necklace to betray and kill her father. In another version, she fell in love with Minos from a distance, and after cutting off her father’s purple lock, she presented it to Minos. However, Minos was disgusted with her act, calling her a disgrace. As Minos’s ships set sail, Scylla attempted to climb up one of them, but Nisos, who had turned into a sea eagle, attacked her, and she fell into the water and drowned. She was changed into a bird, possibly a heron, constantly pursued by Nisos.

The specific name is derived from French garde (‘watchman’, ‘guard’) and barré (‘barred’).

Gabar goshawk, Augrabies National Park, South Africa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Milvus Larger kites

A small genus of 3-4 species, erected in 1799 by French naturalist Bernard Germain de Lacépède (1756-1825). The generic name is the Latin name of the red kite (M. milvus).

Milvus aegyptius Yellow-billed kite

This bird was previously regarded as a subspecies of the black kite (M. migrans), but is readily identified by its yellow bill. It is common from the Sahel zone southwards to South Africa, only absent from the Congo Basin rainforest. It is also found in Madagascar, the Nile Valley, and western Arabia.

Yellow-billed kites, Lalibela, Ethiopia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Necrosyrtes monachus Hooded vulture

This small vulture, the only member of the genus, used to be very common in West Africa, from Senegal eastwards to Chad, and in eastern Africa, from Sudan and Ethiopia southwards to north-eastern South Africa. It was much scarcer in central Africa, Angola, and Namibia. Like all African vultures, it has declined steadily, in some places with as much as 85% population loss over the last 50 years. Threats include poisoning, hunting, loss of habitat, and collisions with electric wires.

The generic name is derived from the Greek nekros (‘corpse’) and syro (‘to drag’). The specific name is a Latinized version of the Greek monakhos (‘monk’, i.e. ‘hooded’), alluding to the almost naked head and neck.

Hooded vulture, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Preening hooded vultures, Debre Mariam, Lake Tana, Ethiopia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Neophron percnopterus Egyptian vulture

This small species, the only member of the genus, has a very wide distribution, found from the Mediterranean eastwards across the Middle East to Kazakhstan and the Indian Subcontinent, and in the Sahel Zone of Africa, southwards to northern Tanzania. It also once had a resident population in Angola, Namibia, and South Africa, which is now considered extinct.

Three subspecies are currently recognized, the nominate northern and African birds, which have a mainly grey bill, Indian birds of subspecies ginginianus with a yellow bill, and finally a separate, larger subspecies, majorensis, in the eastern Canary Islands.

It lives in open areas, nesting on cliffs, less frequently in trees. Besides feeding on carcasses, it is often encountered at rubbish dumps, and it will also prey on small mammals, birds, and reptiles. It is among the few bird species known to use tools. Eggs of other birds, which are too large to break open with the bill, are broken by tossing stones onto them, using the bill.

This species is also in decline over much of its range due to habitat destruction, hunting, poisoning, and collision with power lines.

The generic name stems from the Greek mythology. Neophron and Aegypius were young men and close friends, but it upset Neophron that his mother Timandra was having a love affair with Aegypius. To punish Aegypius, Neophron made advances towards Aegypius’ mother, Bulis. He succeeded and enticed Bulis into entering the dark chamber where his mother and Aegypius were soon to meet. Neophron then distracted his mother, tricking Aegypius into entering the chamber and sleeping with his own mother. When Bulis discovered the deception, she gouged out the eyes of her son before killing herself. Aegypius prayed for revenge, but Zeus, instead of helping him, changed both young men into vultures as a punishment.

The specific name is derived from the Greek perknos (‘dark-coloured’) and pteron (‘wing’).

In ancient Egypt, the bird was held sacred to the Moon God Isis, and its protection by Pharaonic law made it common in the streets, giving rise to the name pharaoh’s chicken.

Preening Egyptian vultures, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Polemaetus bellicosus Martial eagle

A very large and powerful eagle, native almost throughout Africa south of the Sahara, although avoiding rainforest areas. It primarily hunts by soaring and then suddenly pouncing on its prey.

It is the sole member of the genus. The generic name is from the Greek polemos (‘battle’, ‘war’) and aetos (‘eagle’). The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘aggressive’, derived from bellum (‘war’).

Martial eagle, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This martial eagle in Serengeti National Park, Tanzania, had caught an Abdim’s stork (Ciconia abdimii). As our vehicle got too close, the eagle grabbed the stork with one foot and walked some distance away with it, dragging the carcass along. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stephanoaetus coronatus Crowned eagle

Like the martial eagle, this species lives in Africa south of the Sahara, but its preferred habitat is forest. It is the only living member of the genus, as a second species, the Malagasy crowned eagle (S. mahery) was hunted to extinction, when humans settled on Madagascar.

On average, it is a little smaller than the martial eagle, but is just as powerful, living mainly on mammals such as duikers, rock hyraxes, and monkeys.

The generic name is derived from the Greek stephanos (‘crown’) and aetos (‘eagle’), like the specific and common names alluding to a fairly large and bushy crest on the crown.

Crowned eagle , Tarangire National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young crowned eagle, calling, Arusha National Park, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Terathopius ecaudatus Bateleur

This eagle, the only member of the genus, is very characteristic when in flight, due to the extremely short tail, with the feet extending beyond the tail. This is the cause of the specific name, from the Latin ex (‘without’), cauda (‘tail’), and atus (‘provided with’), thus ‘not having a tail’. In fact, only adult birds have a very short tail. The tail of juveniles is longer, but becomes shorter with each moulting.

The generic name is derived from the Greek teras (‘wonder’, ‘marvel’) and ops (‘appearance’), presumably referring to the exceptional flight style of this bird, which twists and turns, often making somersaults. This is probably also the reason for the common name bateleur, French for ‘street performer’, but originally meaning ‘a tightrope walker or balancer’.

The bateleur is widely distributed in open areas south of the Sahara, avoiding rainforest and the Somali Desert.

Bateleur, Tarangire National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bateleur, Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ecaudatus – the bird without a tail. – Bateleur, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Torgos tracheliotos Lappet-faced vulture

This massive vulture, also known as Nubian vulture, is the only member of the genus. It is easily identified by the naked, blue and red face with wrinkled, flesh-coloured lappets (loose skin) on the side of the head and neck. It lives in dry, open areas, including savannah, thorny shrubland, deserts with scattered trees, and open mountain slopes.

It is widely distributed from the Sahel Zone and southern Egypt southwards to northern South Africa, and also on the Arabian Peninsula. It has disappeared from many areas, and is still in decline.

The generic name is an Ancient Greek word for vulture, whereas the specific name is derived from the Greek trakhelia (‘meat scraps of the neck’), ultimately from trakhelos (‘neck’); and ous (‘ear’).

Lappet-faced vulture and tawny eagles (Aquila rapax), resting in an acacia, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lappet-faced vulture, Tarangire National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lappet-faced vulture, feeding on a white-bearded wildebeest calf (Connochaetes taurinus ssp. mearnsi), Serengeti National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Trigonoceps occipitalis White-headed vulture

This striking white and black vulture, with naked, bluish and reddish skin in the face, is widely distributed south of the Sahara, southwards to Namibia and northern South Africa, but absent from rainforest and desert. It has been declining drastically in later years due to habitat destruction and poisoning.

The scientific name is derived from the Greek trion (‘three’) and gonia (‘angle’), the Latin –ceps (‘-headed’), and the Latin occipitium (‘the back of the head’), thus ‘the one with the angled back of the head’ – a most descriptive name.

White-headed vulture with a bone, Ngorongoro Conservation Area, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

White-headed vultures, resting in an acacia, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Soaring white-headed vulture, Serengeti National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Alaudidae Larks

This family contains 21 genera with about 100 species, distributed in Africa and Eurasia, with a single species reaching the Americas, and a single species in Australia.

Ammomanes Desert larks

Following genetic research, this genus now contains only 3 species, whereas 4 others have been moved to other genera. The 3 remaining species are distributed from northern Africa eastwards to Kazakhstan and the Indian Peninsula.

The generic name is derived from the Greek ammos (‘sand’) and manes (‘passionately fond of’), from mania (‘passion’), alluding to the fact that these birds mainly live in sandy areas.

Ammomanes deserti Greater desert lark

This species is widely distributed in northern Africa, from Morocco and Mauritania eastwards to the Red Sea, along the coast to Somalia, and also in Arabia and the Middle East, eastwards to Kazakhstan and the Thar Desert of north-western India.

Greater desert lark in morning sun, Seldja, near Metlaoui, Tunisia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calandrella

This small genus of 6 species was introduced in 1829 by German naturalist Johann Jakob von Kaup (1803-1873), who believed in a strict mathematical order in nature, classifying plants and animals based on the rather strange Quinarian system, with emphasis on the number five: it proposes that all taxa are divisible into five subgroups, and if fewer than five subgroups are known, quinarians believed that a missing subgroup remained to be found.

The generic name is a diminutive of Ancient Greek kalandros, the calandra lark (Melanocorypha calandra). Apparently, Kaup found that the type species, the greater short-toed lark (C. brachydactyla) resembled a small calandra lark.

A number of species, which were previously placed in this genus, have been moved to other genera.

Calandrella cinerea Red-capped lark

A widespread bird, distributed in open areas from Zaire, Uganda, and Kenya southwards to the southern tip of the continent, with an isolated population on the Jos Plateau in Nigeria.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘ash-grey’ – a strange name for this species with its reddish cap, brown upper parts, and whitish underside.

Singing red-capped lark, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calendulauda

Members of this genus, altogether 8 species, were previously placed in the genus Mirafra. They are restricted to Africa south of the Sahara.

The generic name is a combination of two other generic names of larks, Calendula and Alauda.

Calendulauda sabota Sabota lark

Distributed in southern Africa, from Angola and Zimbabwe southwards to South Africa. It lives in grasslands and shrubberies.

The specific name is derived from the Tswana word sebotha, the name for various larks.

Sabota lark, Etosha National Park, Namibia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Eremopterix Sparrow-larks

These small larks, comprising 8 species, were named due to their resemblance to sparrows. They are found all over Africa, except the northernmost part and rainforest areas, and in Madagascar, the southern part of Arabia, southern Iran, and the Indian Subcontinent.

The generic name is derived from the Greek eremos (‘desert’) and pteron (‘wing’), i.e. ‘birds of the desert’.

Eremopterix leucopareia Fischer’s sparrow-lark

This bird is found from extreme eastern Zaire and northern Kenya southwards to eastern Zambia, northern Malawi, and north-western Mozambique. Its natural habitat is grasslands.

The specific name is derived from the Greek leukos (‘white’) and pareion (‘cheek’). The common name commemorates German explorer Gustav Adolf Fischer (1848-1886), who explored parts of East Africa 1876-1886. Shortly after returning to Germany he died of a bilious fever, contracted during his travels.

Fischer’s sparrow-lark, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mirafra Bushlarks

As of today, this genus contains about 24 species, distributed in sub-Saharan Africa, southern parts of Asia, and Australia. Following genetic studies, many other former members have been moved to other genera.

The etymology of the generic name is obscure.

Mirafra africana Rufous-naped lark

This bird, comprising no fewer than 23 subspecies, is very widely distributed in eastern and southern Africa, and also has scattered populations in the Sahel zone and Somalia. Its habitat is a wide variety of grasslands.

Singing rufous-naped lark, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mirafra hypermetra Red-winged lark

This species is found at scattered locations in savannas of eastern Africa, from South Sudan and Ethiopia southwards to northern Tanzania.

Red-winged lark, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Alcedinidae Kingfishers

Kingfishers, comprising about 114 species of small to medium-sized, often brilliantly coloured birds, are characterized by having a large head, a long, sharp, pointed bill, and very short legs. As their name implies, most of these birds eat fish, although many species live away from water, eating mainly small invertebrates.

These birds are divided into 3 subfamilies: river kingfishers (Alcedininae), tree kingfishers (Halcyoninae), and water kingfishers (Cerylinae).

Ceryle rudis Pied kingfisher

This species, the only member of the genus, has a very wide distribution, found in sub-Saharan Africa and Egypt, and in Asia, from Turkey eastwards across the Middle East, the Indian Subcontinent, and Indochina to south-eastern China.

The generic name is derived from the Greek kerylos, an unidentified bird mentioned by scientist and philosopher Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) and other authors. This bird was probably mythical, associated with the halkyon (see genus Halcyon below).

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘rude’ or ‘uncultivated’. This strange name was applied by Swedish naturalist Fredrik Hasselquist (1722-1752) who probably confused the Latin word hispida (‘kingfisher’) with hispidus (‘rough’ or ‘rude’).

Pied kingfisher, Lake Awassa, Ethiopia. Another picture of this species is found at the top of this page. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Corythornis

A small genus of 4 species, 2 of which are found in sub-Saharan Africa, 2 on Madagascar. They were previously included in the genus Alcedo.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek korys (‘helmet’) and ornis (‘bird’), alluding to the bushy crest of the malachite kingfisher (below).

Corythornis cristatus Malachite kingfisher

This bird is rather common in lakes and along slow-moving rivers south of the Sahara, being absent from the Somali Desert and some parts of south-western Africa.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘crested’. The common name refers to malachite, a mineral that owes its green colour to a high content of copper. The upperparts and crown of this kingfisher are bright blue, so the common name is far from descriptive. However, some specimens has a greenish-blue band on the forehead.

Malachite kingfisher, Lake Naivasha, Kenya. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Halcyon

A genus of 11 medium-sized kingfishers, distributed in warmer areas of Africa and Asia.

The generic name is associated with a bird of Greek legend, called halkyon, generally thought to be the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis). The Ancients believed that this bird made a floating nest in the Aegean Sea and had the power to calm the waves while brooding her eggs. Two weeks of calm weather were to be expected when the halkyon was nesting, which took place around winter solstice. These halkyon days were generally regarded as beginning on the 14th or 15th of December.

This belief in the bird’s power to calm the sea originated in a myth recorded by Roman poet Publius Ovidius Naso (43 B.C. – c. 17 A.D.), known as Ovid. The story goes that Aeolus, ruler of the winds, had a daughter named Alcyone, who was married to Ceyx, the king of Thessaly. Ceyx drowned at sea, and in her grief, Alcyone threw herself into the waves. However, instead of drowning, she was transformed into a bird and carried to her husband by the wind. (Source: phrases.org.uk)

Halcyon albiventris Brown-hooded kingfisher

This bird is very widely distributed south of the Sahara, from Congo eastwards to southern Somalia and thence southwards to Namibia and South Africa. It lives in woodland, shrubberies, grasslands with trees, farmland, parks, and gardens, occurring from the lowland up to an elevation of about 1,800 m.

The specific name is derived from the Latin albus (‘white’) and ventris (‘belly’).

Brown-hooded kingfisher, sitting on a fence, Narunyu, southern Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Brown-hooded kingfisher, Msumbugwe Forest, northern Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Halcyon leucocephala Grey-headed kingfisher

A bird of various types of forest, especially riverine woodland. Nests have been found in riverbanks. It is quite common south of the Sahara, from Mauritania and Senegal eastwards to Ethiopia and Somalia, and thence southwards to South Africa, although absent from the southernmost part. It is also found on the Cape Verde Islands and in southern Arabia.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek leukos (‘white’) and kephale (‘head’), although the head is grey rather than white.

Grey-headed kingfisher, Meru National Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Portraits of a grey-headed kingfisher, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Halcyon senegalensis Woodland kingfisher

A striking bird, blue and black above, bluish-grey on the underside, with a distinctive bicoloured bill: the upper mandible is red, the lower black. It has about the same distribution as the previous species, being absent from most of South Africa, and deserts.

Woodland kingfisher, Litipo Forest, southern Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ispidina

This genus contains only 2 African species, closely related to members of the genus Corythornis.

The generic name is from the Latin hispida (‘kingfisher’).

Ispidina picta African pygmy kingfisher

This tiny kingfisher is widespread in forested areas south of the Sahara, being absent from the Somali Desert and large parts of south-western Africa.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘painted’, alluding to the colourful plumage of this bird.

African pygmy kingfisher, Rondo Forest, southern Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Megaceryle Giant kingfishers

A genus of 4 very large kingfishers, found in Africa, southern Asia, and the Americas.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek megas (‘great’), and the genus name Ceryle (above).

Megaceryle maxima Giant kingfisher

The largest kingfisher in Africa, growing to 46 cm long, and having a large crest. The male is chestnut-coloured on the upper breast, the female on the lower belly. It is widely distributed in wetlands south of the Sahara, but absent from desert areas.

Female giant kingfisher, illuminated by late afternoon sunshine, Katima Mulillo, Namibia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anatidae Ducks, geese, and swans

At present, this large worldwide family contains 43 genera with about 146 species.

Alopochen aegyptiaca Egyptian goose

This bird is very common in wide areas south of the Sahara and in the Nile Valley. It was considered sacred by the Ancient Egyptians, often appearing in their artwork. Due to its tameness and beauty, it was introduced to Britain in the 1700s, and later to other European countries, the United States, and New Zealand. It has become naturalized in many places in Europe, where it competes with indigenous geese and ducks. It has been declared a pest in several countries, where it may be hunted year-round, but few birds are bagged, and the species is still expanding.

The generic name is derived from the Greek alopex (‘fox’) and chen (‘goose’), alluding to the ruddy colour around the eye, and on the hindneck, back, and inner flight feathers. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘of Egypt’.

A pair of Egyptian geese, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Egyptian geese, having a dispute, Lake Manyara National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Egyptian goose, Ngorongoro Crater. In the background lesser flamingos (Phoeniconaias minor, see Phoenicopteridae). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Preening Egyptian goose, Ngorongoro Crater. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anas

Following genetic studies, this formerly very large genus has been divided into 7 genera, including Spatula (below). Today, the genus contains 31 species.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for duck.

Anas capensis Cape teal

A medium-sized duck, sexes alike, head pale grey with numerous darker dots, underside whitish with brown bars, wing and back feathers dark brown with pale brown edges. The bill is pink with a black base. In flight, the wing shows a large white patch with a green and black centre. This species is widely distributed, found from Angola and Zambia southwards, with isolated populations in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania. It prefers saltwater wetlands, but may occasionally be observed in freshwater habitats.

Cape teal, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anas erythrorhyncha Red-billed duck

This bird is easily identified by its brownish plumage, blackish-brown cap and hindneck, and the reddish bill. It is widely distributed, from Eritrea southwards through eastern Africa to southern Africa, including Angola and Namibia, and also on Madagascar.

The specific name is derived from the Greek erythros (‘red’) and rhynchos (‘bill’).

Resting and preening red-billed ducks, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anas sparsa African black duck

Like the North American harlequin duck (Histrionicus histrionicus), the South American torrent duck (Merganetta armata), and the blue duck (Hymenolaimus malacorhynchos) of New Zealand, the habitat of the African black duck is fast-flowing rivers.

This species is sooty-brown or dark chocolate-brown with white bars on back and rump, bill dark with a white base. It is distributed in the major part of Africa, from the Sahel zone and Ethiopia southwards to South Africa, but avoids the rainforest areas of central Africa.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘speckled’.

This pair of African black duck are feeding above the Mare Dam, Nyanga National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anas undulata Yellow-billed duck

This species resembles the red-billed duck (above), but the head is uniform pale brown, and the bill is bright yellow with a dark centre. It is found from Ethiopia southwards through eastern Africa to southern Africa, including Angola and Namibia, with an isolated population in Cameroun.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with wavy markings’, alluding to the pattern on the underside of this species.

Yellow-billed duck, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cyanochen cyanoptera Blue-winged goose

This bird is endemic to the central highlands of Ethiopia, living along rivers and in marshes. It is the only member of the genus, and genetic research indicates that it belongs to an ancient clade.

The scientific names are derived from Ancient Greek kyaneos (‘dark blue’), chen (‘goose’), and pteron (‘wing’), thus ‘blue goose with a blue wing’.

Blue-winged goose, west of Dinsho, Bale Mountains, Ethiopia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dendrocygna Whistling-ducks

A genus of 8 species, distributed worldwide in tropical and subtropical areas.

The generic name is derived from the Greek dendron (‘tree’) and kyknos (‘swan’), alluding to the fact that these ducks often breed in tree cavities, and to their fairly long neck. Several members have clear, whistling calls, which gave rise to the popular name.

Dendrocygna bicolor Fulvous whistling-duck

This fulvous-coloured duck has a huge distribution area, found in Florida, southern Texas, the Caribbean, much of Mexico, northern and eastern South America, large areas of sub-Saharan Africa, Madagascar, and eastern and north-eastern India. It lives in wetlands, including shallow lakes and rice fields, nesting among dense vegetation or in a tree hole.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘of two colours’, presumably alluding to the black wings, contrasting with the fulvous body.

Mixed flock of water birds, dominated by fulvous whistling-ducks, Lake Chale, Bangweulu Swamps, Zambia. Also present are white-faced whistling-ducks (Dendrocygna viduata, below), grey-headed gulls (Chroicocephalus cirrocephalus, see Laridae), and 3 African skimmers (Rynchops flavirostris, left). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A pair of fulvous whistling-duck, Bangweulu Swamps. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dendrocygna viduata White-faced whistling-duck

This beautiful duck is often seen in large flocks, occasionally in the hundreds. It is widely distributed in sub-Saharan Africa, Madagascar, and northern and eastern South America. A population in Florida is probably established from escaped birds.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘widowed’, from viduare ‘to be deprived of’, in this connection meaning ‘in mourning’, alluding to the black hindneck and neck of the bird, which somewhat resembles a mourning veil.

White-faced whistling-ducks, Lake Awassa, Ethiopia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

White-faced whistling-ducks, Lake Manyara National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

White-faced whistling-ducks, taking off, Bangweulu Swamps, Zambia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nettapus Pygmy geese

A small genus of 3 species of tiny ducks, the African pygmy goose (below), the cotton pygmy goose (N. coromandelianus), found in the Indian Subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and northern Australasia, and finally the green pygmy goose (N. pulchellus) of northern Australia and southern New Guinea.

Traditionally, these birds are called pygmy geese, although genetic research indicates that they are more closely related to dabbling ducks than to geese. The name alludes to the short, goose-like bill.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek netta (‘duck’) and pous (‘foot’), Apparently, German naturalist Johann Friedrich von Brandt (1802-1879), who erected the genus in 1836, regarded these birds as a kind of small geese due to their short bill, but also found that they possessed the feet and body of a duck.

Nettapus auritus African pygmy goose

This colourful duck is widespread south of the Sahara, only missing in the south-western part and in the rainforest area of central Africa. It also lives in Madagascar. It is partial to freshwater wetlands with floating vegetation, especially water lilies (Nymphaea).

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with large ears’, referring to the large green patch on the side of the neck.

A pair of African pygmy geese (male left), Bangweulu Swamps, Zambia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Oxyura Stiff-tailed ducks

These ducks, comprising 6 species, are very distinctive, often raising their tail upwards. They are found across large parts of the globe, with 3 species in the Americas, one in Africa, one in southern Europe, the Middle East, and Central Asia, and one in Australia.

Breeding males are a rich chestnut brown, females and non-breeding males brownish.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek oxys (‘sharp’) and oura (‘tail’).

Oxyura maccoa Maccoa duck

The male is very distinctive in breeding plumage, with blackish head, chestnut body, and a large blue bill. Female and non-breeding male are dark brown with white head stripes. It lives in freshwater wetlands, but may occasionally be observed in saline lakes.

This species has two disjunct breeding areas, from Eritrea southwards to Tanzania, and from Namibia and Zimbabwe southwards to the Cape Province.

The maccoa duck was named by the Boer, who apparently found that it resembled the domestic Muscovy duck, which, for some reason or other, they called makou. This was then corrupted to maccoa. In fact, the word makou is of Chinese origin, referring to the Portuguese enclave Macau.

Male maccoa duck in breeding plumage, and a female with ducklings, Daan Viljoen National Park, Namibia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Plectropterus gambensis Spur-winged goose

This large bird differs from other geese in a number of anatomical features, and for this reason it has been placed in a separate subfamily, Plectropterinae. It is common in wetlands throughout Africa south of the Sahara, with the exception of the African Horn and some rainforest areas of central Africa.

The diet of this species includes blister beetles of the family Meloidae, which contain a poison, cantharidin. This poison is stored in its meat, and if you eat it, you may easily get poisoned. 10 mg of cantharidin is enough to kill a human.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek plektron (‘to sting’) and pteron (‘wing’), alluding to the spur on the wing. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘from the Gambia’. The type specimen was collected there. It was called the ‘Gambo-Goose’ by English naturalist John Ray (1627-1705) and was illustrated in the seminal work Ornithologiae Libri Tres (1676), which Ray wrote together with his friend and colleague Francis Willughby (1635-1672). Ray was pleased that the plates were “the best and truest, that is, most like the live Birds, of any hitherto engraven in Brass.”

Spur-winged goose, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

‘Gambo-Goose’, illustrated in Ornithologiae Libri Tres. (Public domain)

Sarkidiornis melanotos Knob-billed duck

This peculiar duck, with a large protuberance on the bill, is widely distributed in tropical wetlands in the Indian Subcontinent, Indochina, sub-Saharan Africa, and Madagascar. Previously, the very similar American comb duck, which lives in South America, was included in this species, but today many authorities regard it as a separate species, named S. sylvicola.

The generic name is probably derived from Ancient Greek sarx (‘meat’, or ‘body’) and ornis (‘bird’), maybe alluding to the compact body of the bird. The specific name is also from the Greek, from melas (‘black’) and noton (‘back’).

Knob-billed ducks, Bangweulu Swamps, Zambia. In the background a blue-billed teal (Spatula hottentota), and near the papyrus swamp African pygmy geese (Nettapus auritus). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spatula Shovelers and allies

Members of this genus, comprising 10 species of shovelers and teals, were formerly placed in the genus Anas. The genus Spatula had originally been proposed in 1822 by German zoologist and lawyer Friedrich Boie (1789-1870), who described many new species and several new genera of birds. He and his brother Heinrich also described about 50 new species of reptiles.

The generic name is the Latin word for ‘spoon’ or ‘spatula’, alluding to the spatulate bill of shovelers.

Spatula hottentota Blue-billed teal, Hottentot teal

A very pretty duck with fulvous underside, dark brown cap, and blue bill. It is widely distributed in freshwater habitats, from South Sudan and Ethiopia southwards through eastern Africa to southern Africa, including Angola and Namibia, and also on Madagascar.

The specific name refers to the word Hottentot, which was the Boer term for the Khoisan people. However, this was a derogative term, and in later years many authorities have changed the popular name to blue-billed teal.

Feeding blue-billed teals, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. The small wader is a little stint (Calidris minuta, see Scolopacidae). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anhingidae Darters

Darters, also called snakebirds due to their long, thin, flexible neck, are large water birds, comprising two or four species in the genus Anhinga, the sole genus of the family. The American darter (A. anhinga), often called anhinga, lives in the New World.

One or three species are found in the Old World. If only one species is acknowledged, it is called A. melanogaster. Most authorities, however, recognize three full species: Oriental (A. melanogaster), African (below), and Australasian (A. novaehollandiae).

The generic name means ‘little head’ in the Tupi language of Brazil, referring to an evil spirit of the forests, the devil bird. (Source: G. Marcgrave 1648. Historiae rerum naturalium Brasiliae. Liber V)

Anhinga rufa African darter

Widespread and common in sub-Saharan Africa and Madagascar. One subspecies, chantrei, was previously found in south-central Turkey, in northern Israel, and in the marshes of southern Iraq. Today, this subspecies is almost extinct. A tiny population still lives in the remnants of the marshes of Iraq.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘rufous’.

African darters in rainy weather, Huntley’s Farm, Zambia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ardeidae Herons, egrets, and bitterns

Herons, comprising 18 genera with about 64 species, are long-legged and long-beaked, fish-eating water birds, distributed worldwide with the exception of the polar regions. Some species are called egrets, mainly birds with ornate plumes during the breeding season, whereas birds of the genera Botaurus, Ixobrychus, and Zebrilus are called bitterns.

Many members of the family are presented on the page Fishing.

Ardea

A genus with about 13 species of mainly large herons, distributed almost worldwide. The generic name is the classical Latin word for herons.

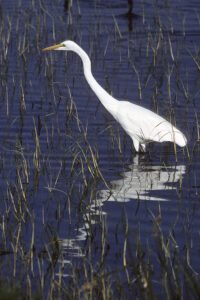

Ardea alba Great white egret

This large heron has an almost global distribution, found in Europe, Africa, most of Asia, Australia, and the Americas. Traditionally, it was placed in the genus Egretta (below), mainly due to its white plumage. Some authorities have also placed it in a separate genus, Casmerodius. However, it shows many affinities to large herons in the genus Ardea.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘white’.

Feeding great white egret, Lake Awassa, Ethiopia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ardea goliath Goliath heron

This bird resembles the purple heron (below), but is larger, with a much heavier bill. In fact, it is the world’s largest heron, up to 1.5 m tall and with a wingspan up to 2.3 m.

It is fairly common in Africa south of the Sahara, southwards to northern Namibia and Botswana, and north-eastern South Africa. Small numbers are also found in the marshes of southern Iraq, in southern Iran, and in Yemen.

Goliath heron, feeding in a swamp with water hyacinths (Eichhornia crassipes), Lake Naivasha, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Goliath heron, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ardea intermedia Yellow-billed egret, intermediate egret

This bird resembles a smaller edition of the great white egret (above). It has a very wide distribution, found in sub-Saharan Africa, the Indian Subcontinent, East and Southeast Asia, and Australia. In East Asia, it breeds as far north as South Korea and southern Japan. These northern birds are migratory, spending the winter in Taiwan, the Philippines, Indochina, and Indonesia.

The specific name refers to its size, intermediate between the great white egret and the little egret (Egretta garzetta, below).

Some authorities place this bird in a separate genus, Mesophoyx.

Yellow-billed egret, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ardea melanocephala Black-headed heron

A widespread and common species south of the Sahara. As opposed to most other herons, it often feeds quite far away from water.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek melas (‘black’) and kephale (‘head’).

Black-headed heron, feeding in a tall-grass savanna, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Black-headed heron, resting on a tree stump, Serengeti National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Resting and preening black-headed herons, Lake Legaja, Serengeti National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ardea purpurea Purple heron

This species is very widely distributed, breeding in Africa south of the Sahara, on Madagascar, in central and southern Europe, around the Mediterranean eastwards to Kazakhstan, from Pakistan eastwards to China and Siberian Ussuriland, and thence southwards to the Philippines and Indonesia.

Purple heron, resting in papyrus (Cyperus papyrus), Lake Naivasha, Kenya. The plants in front are water hyacinths (Eichhornia crassipes). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Purple heron, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ardeola Pond herons

A genus of 6 species of small herons, most of which are found in tropical areas of Asia and Africa. One species, the squacco heron (below), also breeds in southern Europe and the Middle East.

Most of the year, the plumage of these birds is buff or brownish, making them extremely well camouflaged among various types of vegetation. When they take to flight, however, they are transformed as if by magic, when their brilliant white wings are displayed.

The generic name is from the Latin ardea (‘heron’) and –ola, a suffix denoting something diminutive, thus ‘small heron’.

Ardeola ralloides Squacco heron

This bird breeds in eastern and south-eastern Africa, in scattered locations in West Africa, on Madagascar, and around the Mediterranean, eastwards to Kazakhstan and Iran. Northern populations are migratory, spending the winter in Africa and Arabia.

The specific name is derived from Rallus, the generic name of certain rails, and Ancient Greek –oides (‘resembling’), thus ‘resembling a rail’.

Squacco heron, Lake Awassa, Ethiopia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bubulcus ibis Cattle egret

This species, in my opinion the sole member of the genus, is very widely distributed, found in most warmer areas of the world, only avoiding rain forests and desert areas.

Originally, this bird was native to southern Spain and Portugal, the northern half of Africa, and across the Middle East and the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to Japan, and thence southwards to northern and eastern Australia. In the late 1800s, it began expanding its range into southern Africa, and in 1877 it was observed in northern South America, having apparently flown across the Atlantic Ocean. By the 1930s, it had become established as a breeding bird in this area, rapidly spreading to North America, where it is now found as far north as southern Canada. In later years, it has also spread northwards in Europe.

As its name implies, it often follows cattle to snap grasshoppers and other small animals, flushed by the grazers. It is also often observed in newly ploughed fields. The generic name is Latin, meaning ‘cowherd’. The specific name is the Ancient Greek term for ibises. Why it was applied to the cattle egret is not clear.

Today, some authorities split the cattle egret into two species, the western (B. ibis) and the eastern (B. coromandus). Apart from minor differences, they are identical, so why this split was made, is a bit of a mystery to me.

Swamp with resting cattle egrets, African spoonbills (Platalea alba), and a single black-winged stilt (Himantopus himantopus), Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cattle egrets, using the backs of African buffalos (Syncerus caffer) as a lookout point, Queen Elizabeth National Park, Uganda. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cattle egrets on resting hippos (Hippopotamus amphibius), Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Butorides

Most authorities recognize 3 small herons of this genus as separate species, the striated heron (below), the green heron (B. virescens) of North and Central America, and the lava heron (B. sundevalli), which is endemic to the Galapagos Islands. Others regard them as being conspecific.

The generic name is derived from Middle English botor (‘bittern’), and from Ancient Greek –oides (‘resembling’).

Butorides striata Striated heron

This small heron, also known as mangrove heron or green-backed heron, is widespread in South America, in Africa south of the Sahara, around the Red Sea, in south-eastern Arabia, and from Pakistan eastwards to Japan and the Philippines, and thence southwards to Australia. North-eastern populations in Asia are migratory.

Striated heron, subspecies rhizophorae, feeding in a tidal pool, Iconi, Grande Comore, Comoro Islands. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Looking for fish in a small stream, this striated heron seems petrified. – Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Egretta Egrets

A genus of 12 small to medium-sized herons, the major part breeding in warmer areas around the globe. Most members have black legs with bright yellow toes, and many develop ornate plumes during the breeding season.

The generic name is derived from Provençal French aigrette, a diminutive of aigron (‘heron’).

Egretta dimorpha Dimorphic egret

A coastal species, which breeds on coral islets along the coasts of Madagascar, the Comoro Islands, the Seychelles, Kenya, and Tanzania. It mainly feeds in pools in exposed, fossilized coral reefs. As its name implies, this species comes in two morphs, one white, although sometimes with a darker shade, and one slate-coloured.

It is often debated among scientists, whether the dimorphic egret is a separate species, or a subspecies of the little egret, or of the western reef heron (both below). A review of the complex relationship between these species has been made by Don Turner. (The Egretta garzetta complex in East Africa: A case for one, two or three species. Scopus. Journal of East African Ornithology, Vol. 30, 2010)

Today, most authorities regard the 3 birds as separate species.

Dimorphic egrets, pale and dark morphs, and sooty gulls (Ichthyaetus hemprichii), Kunduchi Beach, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. In the background, fishermen are pulling in their net. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dark morph dimorphic egrets, feeding on mudflats, Rufiji River, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A pale morph dimorphic egret takes off, Shungu Mbili Island, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Egretta garzetta Little egret

The little egret is found in most tropical and subtropical areas of Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia. In 1994, a small population was established on the Caribbean island Barbados, and the species has since spread to other Caribbean islands and to the Atlantic coast of the United States.

The specific name is the Italian name for the bird.

Little egret, Lake Awassa, Ethiopia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Egretta gularis Western reef heron

This coastal species is divided into two subspecies, gularis, which is found in West Africa, from Mauritania southwards to Gabon, and schistacea, which is distributed in the Red Sea, from Sinai southwards to Somalia, in the Persian Gulf, and along coasts of Iran, Pakistan, India, and Sri Lanka.

Like the dimorphic egret, this bird has two colour morphs, black and white.

The specific name is derived from the Latin gula (‘throat’), presumably referring to the white throat-patch of the dark morph.

Western reef heron, dark morph of subspecies schistacea, feeding among mangrove roots, Nabq, Sinai, Egypt. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Western reef heron, pale morph, Nabq, Sinai. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bucerotidae True hornbills

These peculiar birds, comprising about 53-57 species, are distributed in tropical Asia and Africa. They vary greatly in size, from the small West African black dwarf hornbill (Horizocerus hartlaubi), which is 30 cm long and weighs only c. 100 grams, to the huge rhinoceros hornbill (Buceros rhinoceros) in Malaysia and Indonesia, growing to about 1.2 m long and weighing up to 5.9 kg.

The family name and the name of the type genus, Buceros, are derived from the Greek bous (‘cow’) and keras (‘horn’), referring to a peculiar protuberance, or casque, on the bill of most species. Hornbills are very noisy, and the casque is probably a means to increase the volume of their call, which carries a long distance. The casque of males is larger than that of females.

A number of Asian species are presented on the page Animals – Birds: Hornbills.

Bycanistes

A genus of 6 large species, living in forests south of the Sahara.

The generic name is a Latinized version of Ancient Greek bykanistes (‘trumpeter’), alluding to the loud call of these birds.

Bycanistes brevis Silvery-cheeked hornbill

This impressive bird is still fairly common, albeit declining, distributed from Ethiopia southwards through eastern Africa to eastern Zimbabwe and extreme north-eastern South Africa.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘short’. What it refers to is a bit of a mystery, as the bird is not at all short, but has a long tail. The popular name was given due to the silvery-grey dots on the side of the head and neck.

Hornbills often call simultaneously, like these silvery-cheeked hornbills, gathered in a tree, Lake Manyara National Park, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Silvery-cheeked hornbill, catching swarming termites, Lake Manyara National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is feeding on fig fruits, Wondo Genet, Ethiopia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bycanistes bucinator Trumpeter hornbill

This species is distributed from Kenya and eastern Zaire southwards through eastern Africa to south-eastern South Africa. It lives in various types of forest, including riverine and coastal forests.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘trumpeter’, from bucina (‘a military trumpet’). This bird must really be trumpeting, as the scientific name means ‘the trumpeting trumpeter’!

Male trumpeter hornbill, sitting on a rock in front of Victoria Falls, or Mosi-oa-Tunya (’the smoke that thunders’), Zambezi River, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This male is feeding on fruits of a fig tree, Zambezi National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bycanistes subcylindricus Grey-cheeked hornbill

This species, also known as the black-and-white-casqued hornbill, lives in rainforests. It has a patchy distribution south of the Sahara, from Guinea eastwards to western Kenya, with an isolated population in north-eastern Angola.

The specific name is from the Latin sub (‘near to’), and cylindricus, the specific name of the brown-cheeked hornbill (B. cylindricus), thus ‘the one resembling brown-cheeked hornbill’. Cylindricus is derived from the Greek kylindros (‘cylinder’), presumably referring to the somewhat cylinder-shaped casque of these two birds.

Grey-cheeked hornbill, swallowing some large insect, Kakamega Forest, western Kenya. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lophoceros

Members of this genus were formerly included in the genus Tockus (below), but have recently been moved to a separate genus. There are 7 species, all found south of the Sahara.

The generic name is derived from the Greek lophos (‘crest’) and keras (‘horn’) – an odd name, as these birds have small casques.

Lophoceros hemprichii Hemprich’s hornbill

This species is mainly an Ethiopian bird, but is also found in southern Eritrea, northern Kenya, and along the Somalian Red Sea coast. It lives in shrubland, forests, and rocky areas, often near water. The sexes are quite similar, but the female has paler red bill than the male.

This bird was named in honour of German naturalist and explorer Wilhelm Friedrich Hemprich (1796-1825), who travelled extensively in Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia. He died of malaria in Ethiopia, only 29 years old.

Female Hemprich’s hornbill, Yabello, southern Ethiopia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lophoceros nasutus African grey hornbill

This bird is very widely distributed south of the Sahara, from southern Mauritania and Senegal eastwards to the Red Sea coast (also on the Arabian side), and thence southwards through Ethiopia, Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania to Mozambique and north-eastern South Africa. From here, it is found westwards to southern Angola and eastern Namibia.

It lives in open woodland and savanna. The male has a black bill, whereas that of the female is blackish, often with reddish or yellowish parts. Both sexes have a conspicuous white stripe on the upper mandible.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘large-nosed’, derived from nasus (‘nose’), referring to the casque, of course.

Male African grey hornbill, observed near the Blue Nile, Ethiopia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tockus

A genus of 6-10 small hornbills, living in grasslands and shrubland south of the Sahara.

The generic name is derived from the French tock, applied to the African grey hornbill and the red-billed hornbill by French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707-1788). Supposedly, this name was based on an onomatopoeic Senegalese name of these birds.

Tockus deckeni Von der Decken’s hornbill

This species is distributed from central Ethiopia and extreme south-eastern South Sudan southwards through Somalia and Kenya to southern Tanzania. It lives mainly in arid shrublands.

It was named in honour of a German explorer, Baron Karl Klaus von der Decken (1833-1865). He was the first European attempting to climb Mount Kilimanjaro, but did not succeed due to foul weather. He also visited Madagascar and the Mascarene Islands. In 1865, he went to Somalia, exploring the lower parts of the Jubba River, on board the small steamship Welf. However, after the ship sank in rapids, he and three others in his party were murdered by hostile Somalis.

Female von der Decken’s hornbill, Awash National Park, Ethiopia. The female has a dark bill, whereas the male has a red bill with an ivory-coloured tip. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tockus erythrorhynchus Red-billed hornbill

Following genetic studies, some researchers claim that this bird should be split into 5 separate species, whereas other authorities still regard them as belonging to a single species. If you follow the latter, the bird is distributed from Mauritania eastwards to Eritrea and Somalia, southwards to Namibia and north-eastern South Africa.

The five species/subspecies are as follows:

The northern red-billed hornbill (T. (e.) erythrorhynchus) is found from southern Mauritania eastwards to Eritrea and Somalia, and thence southwards to Kenya and northern Tanzania.

The western red-billed hornbill (T. (e.) kempi) is distributed from southern Mauritania through Senegal and Gambia to western Mali.

The Tanzanian red-billed hornbill (T. (e.) ruahae) is restricted to central and western Tanzania.

The southern red-billed hornbill (T. (e.) rufirostris) is found from Angola and Namibia eastwards to Zambia, and thence south to north-eastern South Africa.

The Damara red-billed hornbill (T. (e.) damarensis) is restricted to southern Angola and northern and western Namibia.

The specific name is derived from the Greek erythros (‘red’) and rhynkhos (‘bill’).

Northern red-billed hornbill, subspecies erythrorhynchus, feeding in a grassy area, Tarangire National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Northern red-billed hornbill, Meru National Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Southern red-billed hornbill, subspecies rufirostris, Matobo National Park (top), and Hwange National Park, both in Zimbabwe. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tockus flavirostris Eastern yellow-billed hornbill

This bird, also known as northern yellow-billed hornbill, is similar to southern yellow-billed hornbill (below), but has blackish skin around the eyes. It is found in eastern Africa, from Eritrea, Djibouti, and Somalia southwards to extreme south-eastern South Sudan, eastern Uganda, Kenya, and extreme northern Tanzania.

The specific name is derived from the Latin flavus (‘yellow’) and rostrum (‘bill’).

Eastern yellow-billed hornbills, Samburu National Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tockus jacksoni Jackson’s hornbill

This bird resembles von der Decken’s hornbill, but has dense white spots on the wing-coverts. It is restricted to a rather small area in south-eastern South Sudan, south-western Ethiopia, north-eastern Uganda, and north-western Kenya. The population is decreasing.

The name of this species was given in honour of Sir Frederick John Jackson (1860-1929), an English administrator, explorer, and ornithologist, who lived in Kenya.

Male Jackson’s hornbill, Lake Baringo, Kenya. This individual has a very pale head. Usually, males have a dark smudge around the eye. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tockus leucomelas Southern yellow-billed hornbill

This species is distributed from Angola and Namibia eastwards across Botswana and northern South Africa to extreme southern Zambia and Mozambique. It is similar to eastern yellow-billed hornbill (above), but has pinkish skin around the eye and beneath the bill.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek leukos (‘white’) and melas (‘black’), thus ‘black and white’.

Southern yellow-billed hornbill, illuminated by the evening sun, Etosha National Park, Namibia. – This park and other fantastic natural areas in Namibia are presented on the page Countries and places: Namibia – a desert country. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A pair of southern yellow-billed hornbills, greeting each other in the morning sun, Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Southern yellow-billed hornbill, photographed in a campground, Etosha National Park, Namibia. In the background a red-shouldered glossy-starling (Lamprotornis nitens). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Southern yellow-billed hornbills, feeding on insects in elephant dung, Kruger National Park, South Africa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bucorvidae Ground-hornbills

The huge ground-hornbills may grow to about 1.2 m long and weigh up to 6.2 kg. They differ sufficiently from true hornbills (above) to form a separate family, containing only 2 species in the genus Bucorvus.

Their habitat is grasslands with short vegetation and scattered trees, in which they nest. They differ mainly in their feeding habit, as they spend most of their time on the ground, searching for prey like lizards, snakes, and larger insects.

The generic name is composed of two other genus names, Buceros (see above), and Corvus (ravens and crows), thus ‘the hornbills that resemble crows’.

Bucorvus abyssinicus Abyssinian ground-hornbill

This species, also known as northern ground-hornbill, is endemic to Ethiopia (in former times called Abyssinia). It differs from the southern species (below) by its blue wattles and a larger casque. It is declining due to habitat destruction and hunting.

Abyssinian ground-hornbill, photographed near the Genale River, Ethiopia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bucorvus leadbeateri Southern ground-hornbill

This bird is found from Rwanda, Kenya, south-eastern Zaire, and Angola southwards to northern Namibia, northern Botswana, and eastern South Africa. It has been declining in later years.

The specific name refers to Benjamin Leadbeater (1760-1837), an English natural history dealer in London.

Southern ground-hornbill, Lake Manyara National Park, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This southern ground-hornbill walks around in a savanna, catches an insect and swallows it, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Buphagidae Oxpeckers

These birds, comprising two species, were previously regarded as a subfamily of the starlings, but have now been moved to a separate family. They live in Africa south of the Sahara.

They feed mainly on insects and ticks, usually on the skin of large ungulates. It has been observed that in one day a bird may eat more than 100 adult ticks or 13,000 larvae.

However, their preferred food is blood, and they often peck in wounds on animals to make the blood flow, or they may even peck at the skin, making a wound themselves. This behaviour is reflected in the generic name, derived from Ancient Greek bous (‘ox’) and phagos (‘eating’).

Buphagus africanus Yellow-billed oxpecker

Widely distributed in the Sahel zone, from Senegal eastwards to Ethiopia. In southern and eastern Africa, it has a scattered occurrence.

Yellow-billed oxpecker, sitting on the back of a Chapman’s zebra (Equus quagga ssp. chapmani), Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Burhinidae Thick-knees, stone-curlews

These birds comprise about 10 species in two genera, Burhinus and Esacus.

Burhinus Thick-knees, stone-curlews

A genus of 8 species, known as dikkops in South Africa. These birds are widely distributed, from southern Europe across the Middle East to the Indian Subcontinent and Southeast Asia, and thence southwards through Indonesia to Australia, in Africa, in Central America and northern South America, and along coastal Ecuador and Peru. Most species live in dry habitats.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek bous (‘ox’) and ‘rhinos’ (‘nose’, or, in this connection, ‘bill’), alluding to the large bill of these birds. The name thick-knee refers to the swelling of the leg joint.

Burhinus capensis Spotted thick-knee

This bird lives in grasslands and savannas in the Sahel zone, from Senegal and Mauritania eastwards to Ethiopia and Somalia, and thence southwards through eastern Africa to the entire southern Africa. It also occurs a few places in Yemen and Oman.

The specific name refers to the Cape Province.

Spotted thick-knee, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Burhinus vermiculatus Water thick-knee

The habitat of this bird is wetlands, including lakesides, rivers, mangroves, and river deltas, usually surrounded by shrubberies or woodlands. It is distributed from Ethiopia southwards through eastern Africa to the major part of southern Africa, from sea-level up to an elevation of about 1,800 m. It also occurs a few places in West Africa.

The specific name is derived from the Latin vermiculus (‘little worm’), diminutive of vermis (‘worm’). Apparently, German ornithologist Jean Louis Cabanis (1816-1906), who named the bird in 1868, found that the stripes on its body resembled worms.

Water thick-knee, Tarangire National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calyptomenidae Broadbills