Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

India 1997: A night on board an Indian First-Class train

We arrive early at the train station, and after some time our train pulls up. It is not at all obvious, which one of the carriages is First Class, but finally we think we have found it. Its appearance, however, is indeed very shabby, looking more like a wagon, designed for cattle transportation.

“Excuse me, is this the First-Class carriage?” Søren asks a nearby conductor.

The man bends back his head, opens his mouth and says something like: “Gurgle-gurgle-raaah.”

“What does he say?”

“I don’t know. His whole head is full of beetle spit.”

The conductor walks to the edge of the platform and, with remarkable precision, sends a blood-red shower of saliva down between the carriage and the platform.

“Yes, it is,” he says.

We have sleepers in a four-person compartment, called ‘A’. However, the next one, ‘B’, is a two-person compartment, and we get permission from the conductor to swap berths, so that we shall only have to listen to one another’s snoring.

A sign with the text ‘STORE’ is attached to the outside of the sliding door, and this is exactly what the compartment looks like: garbage and dust litter the floor, and nails and screws stick out of the walls, which are mended in several places with an assortment of available pieces of laminated wood and metal. Naturally, the fans don’t work, but luckily it is winter season, so we shall not need them.

When I close the sliding door, I discover something written on the wall behind it: “Unfit for passengers. 7/11-97” (two days prior to our departure).

A few moments later, somebody pounds on the door, and a uniformed man enters.

“Security check! Is this your luggage?”

“Yes.”

He glances at our backpacks, marks them with a squiggle with a piece of chalk, whereupon he disappears.

“No problem!” he says, tearing off the laminated piece of wood, whereupon he pulls out two wires from the hole and separates them.

“But how are we going to get light again?”

“No problem!” he says, joining the two wires again. Light illuminates the room.

We have hardly put our heads on our pillows, before the sliding door is opened with a tremendous noise. We are convinced that we had locked it, but, as we soon learn, the lock mechanism is worn out, and, by using some force, you are still able to open the door.

We blink against the light from the corridor, in which a new conductor requests to see our tickets.

“You have tickets for ‘A’, not for ‘B’. You must move!”

We explain that his colleague gave us permission to swap, and after some negotiations we get permission anew, but on the condition, that should the ‘owners’ turn up, we shall have to move.

Again, we try to get some rest, but with short intervals the door is opened by travellers who want to check, if any space is available. Finally, Søren is able to lock the door securely.

A few minutes later, somebody is again pounding on the door.

“Who is it?” Søren shouts – in Danish. The answer is a shower of Hindi.

“This is occupied!” shouts Søren. More Hindi, and a more powerful pounding on the door.

Søren opens the door, and a policeman, armed with a stick, enters. He glances around and leaves again, not uttering a single word. We mumble a few curses and go back to bed.

The rest of the night passes as peacefully as conditions permit. Still people try to open the door, and there is the usual noise from passengers getting on or off the train. On each and every station, throughout the night, we hear vendors shouting: “Chaii! Chai! Garam chaii!” (“Tea! Tea! Hot tea!”)

Bellies full, we can now watch life on the immense, flat Ganges plains. Village houses are mostly made of clay and straw, often surrounded by groups of mango or fig trees, which cast long morning shadows. Beneath these trees, in the shade, village men will gather in the evening after a long day’s work to talk and smoke a bidi, a ‘poor man’s cigarette’, made from the leaves of a tree, Diospyros melanoxylon.

Beneath small groves of bamboo, whose leaves are fluttering in the morning breeze, carts, pulled by zebu oxen, move at a snail’s pace along bumpy tracks. A group of vultures are fighting with dogs over the remains of a dead cow. Many people are defecating on the railroad slopes, oblivious of the passengers watching.

In a grey and ugly industrial town, numerous chimneys are spewing out ominous columns of black smoke, dimming the landscape, which is already filled with clouds of dust.

We hardly believe our eyes. Pure-bred dogs in India! The dogs gasp and grunt and spread their saliva generously onto our backpacks.

“Please, we have reserved this compartment for our dogs, please leave!” says one of the men. We ask permission to see their reservation, which turns out to be in perfect order. And besides, they did write on the wall that this compartment was ‘unfit for passengers’. Maybe that’s why it has been reserved for the dogs. The men inform us that their dogs have participated in a show in Lucknow, and they are now returning to their home in Calcutta.

Consequently, we pack our belongings, retreating to compartment ‘A’. Luckily, the number of passengers which was stuffed in here, has reduced somewhat, and, consequently, we are able to get our reserved seats without a fight.

On the platform outside, endless arguments are taking place between the conductor and a lot of passengers, who have reservations for First Class, but nowhere to use them.

We invite two Englishmen to share our seats. They woke up in the third First Class compartment, only to find out that, during the night, they had been sharing it with nine other people.

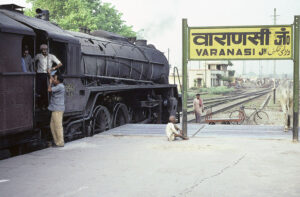

Now three other passengers manage to impose themselves upon us, but we are able to keep the rest out. Without further incidents, the train pulls up at the platform in Varanasi.