Parasitic plants

The archetype of parasitic plants is the common mistletoe (Viscum album), which has a prominent position in European folklore. In this picture, it grows on poplar trees near Le Blanc, central France. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

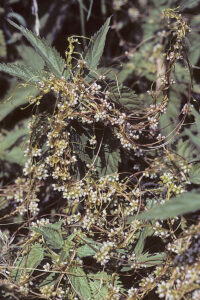

A typical representative of holoparasites is this unidentified species of dodder (Cuscuta), which has completely enveloped a bush in Monumento Natural El Morado, central Chile. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Another holoparasite is cactus mistletoe (Tristerix aphylla), which is partial to two species of cacti in central Chile. In this picture, it grows on the trunk of a quisco (Echinopsis chiloensis), La Campana National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A typical representative of hemiparasites is the whorled lousewort (Pedicularis verticillata), which is native to mountains of Europe, Central Asia, China, Japan, and to arctic areas of Russia, Alaska, and Canada. This picture was taken near the Sölkpass, Austria. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Less than the coral-root you know

That is content with the daylight low,

And has no leaves at all of its own;

Whose spotted flowers hang meanly down.

Extract from the poem On Going Unnoticed, published in West-Running Brook (1928), by American poet Robert Frost (1874-1963), about the spotted coralroot (Corallorhiza maculata, see Orchidaceae below).

Parasitic plants are divided into two main groups: holoparasites, which derive all their nutrients from another living plant or from a fungus, and hemiparasites, which to some extent are able to produce nutrients through photosynthesis. In the Greek, hemi means ‘half’. To me, the term half-parasite seems rather odd. Either you are a parasite, or you are not!

Parasitic plants, comprising around 4,500 species, are known from about 20 different families. They are distributed across virtually the entire planet, but lacking in Antarctica. Almost all species have sucking organs, named haustoria, which are modified roots that penetrate the host plant, extracting water and nutrients from it.

Below, the parasitic plants I have encountered around the world are presented in alphabetical order, according to family, genus, and species.

Balanophoraceae

This family contains 17 genera with about 44 species, some of which superficially resemble fungi. These plants contain no chlorophyll, being holoparasites that obtain all necessary nutrients from tree roots. They are found in subtropical and tropical areas around the globe, with a few species extending into temperate regions.

Balanophora

This genus, comprising about 20 species, is found in tropical Africa, on Madagascar, and from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to Japan, and thence southwards to Indonesia, New Guinea, north-eastern Australia, and some Pacific Islands. Some species emit an odour, which attracts flies as pollinators. Several species are utilized in traditional medicine in certain Asian countries.

The generic name stems from the inflorescence of some members of this genus, which is covered by bumps, resembling barnacles (family Balanidae).

Balanophora dioica

The stems of this plant are pink or purple, cylindric, to 10 cm tall. Leaves are scale-like, clasping the stem, to 4 cm long and 2.5 cm broad. Inflorescences are ovoid or ellipsoid, to 3.5 cm long. This species has a wide altitudinal range, found between 400 and 2,600 m, from central Nepal eastwards to China and Taiwan.

The specific name is from the Latin, meaning ‘having male and female reproductive organs on separate plants’, ultimately from Ancient Greek dis (‘twice’) and oikos (‘house’).

Balanophora dioica, near Bamboo Lodge, Lower Langtang Valley, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Convolvulaceae Morning-glory family

Cuscuta Dodders

Formerly, these plants, comprising 100-170 species, constituted a separate family, Cuscutaceae, but have now been moved to the morning-glory family – the only parasitic members of that family.

They are distributed almost worldwide, with the greatest concentration in the tropics and subtropics. Temperate areas have much fewer species, including northern Europe, where only 4 species are native. In hot climates, dodders are perennials, growing more or less continuously, while in colder areas they are annuals.

These plants twine around other plants, often completely enveloping them in their yellow or reddish stems. A dodder seed starts its life like most other seeds by sending roots into the soil, from which grow stems, whose leaves are reduced to scales. When a stem gets into contact with a suitable plant, it wraps itself around it, inserting haustoria into the plant, through which the dodder obtains water and nutrients. Its root in the ground then dies.

Their strange appearance taken into consideration, it is hardly surprising that dodders have many folk names, including strangleweed, scaldweed, beggarweed, lady’s laces, wizard’s net, devil’s guts, devil’s hair, devil’s ringlet, goldthread, hailweed, hairweed, hellbine, pull-down, angel’s hair, and witch’s hair.

The generic name is derived from the Arabic name of dodders, kusuta, or kuskut, which, in the form Cuscuta, was applied to them by Rufinus, an Italian monk and botanist, who was the author of De virtutibus herbarum, completed c. 1287, which listed nearly a thousand medicinal materials, mostly plants.

Cuscuta australis Southern dodder

This species is very widely distributed, found from southern Europe across the Middle East and Central Asia to Japan, and thence southwards through Indonesia and New Guinea to Australia, and also in India, Africa, and Madagascar.

Stems yellow, sometimes several metres long, flowers in compact clusters, white, very short-stalked, bell-shaped, to 2.5 mm long, corolla with 5 broadly elliptic lobes with rounded tips.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘southern’.

Southern dodder is very common in Taiwan. In this picture, it covers most of the embankment along the Agongdian River, southern Taiwan. The plant with violet flowers is another member of the morning-glory family, Ipomoea pes-caprae. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Southern dodder readily grows in abandoned plots and along drainage canals in cities. These pictures are from Taichung, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cuscuta californica Chaparral dodder

This plant is common in western North America, found from Washington southwards to Baja California, north-western Mexico, and also in Nevada, Utah, and Arizona, growing in grasslands, pine forests, and chaparral, from sea level to elevations around 2,500 m. Chaparral is a community of shrubby plants, adapted to dry summers and moist winters, typical of southern California.

The stems are yellow or orange, with dense clusters of flowers, to 5 mm long, corolla white or cream-coloured, with 5 triangular or lanceolate lobes, calyx yellow, almost as long as corolla.

This chaparral dodder has enveloped a bladderpod bush (Peritoma arborea), near Amboy, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cuscuta europaea Greater dodder

This species is partial to common nettle (Urtica dioica), although it can grow on plants of many other families. The stems are red, orange, or yellowish, about 1 mm thick. The small, short-stalked, urn-shaped flowers, to 3 mm long, are arranged in dense clusters, to 1.5 cm across, along the stem, calyx cup-shaped, sepals 4 or 5, blunt, about 1.5 mm long, corolla pink or whitish, with 4 or 5 triangular or ovate lobes, to 3 mm long, often reflexed.

It is very widely distributed, found in temperate areas of Europe and Asia, eastwards to south-eastern Siberia and Japan, southwards to Morocco, Iran, the Himalaya, and China. It is occasionally encountered in North and South America.

The commonest host of greater dodder is common nettle, as in these pictures from the Lauterbrunnen Valley, Berner Oberland, Switzerland (top), and the island of Møn, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Greater dodder, Spiti, Himachal Pradesh, north-western India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Greater dodder, growing on a species of knapweed (Centaurea), Valle Hecho, Pyrenees, Spain. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cuscuta reflexa Giant Asian dodder

A most proliferate plant, which forms dense masses around even large shrubs. It is more robust than most species in the genus, with intertwining, up to 3 mm thick stems, which may be yellow, greenish, purplish, or brownish, with small fleshy bracts and numerous lateral, branched clusters of flowers, to 5 cm long, corolla white or cream-coloured, sometimes brown-spotted, bell-shaped, fragrant, to 1.1 cm long, with short, triangular or rounded, spreading or reflexed lobes that are often shed. The fleshy capsule is conical or globular, to 1 cm across.

It is widely distributed, found from Afghanistan across the Indian Subcontinent and southern Tibet to southern China, southwards to Sri Lanka and Indochina, with an isolated occurrence on Java. Due to its vigorous growth, it is regarded as a serious pest in many places, including Valley of Flowers National Park, Uttarakhand, northern India.

In Indian folk medicine, the juice is used for treatment of jaundice, a warm paste of the plant for rheumatism and headache. It is also used for urination disorders, muscle pain, and cough, and as a blood purifier. The seeds are used against flatulence, intestinal worms, and liver disorders.

In Nepal, juice from the plant is taken for jaundice, stomach ache, headache, rheumatism, and other ailments. Ash from the burned plant is applied to wounds.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘bent backwards’, alluding to the petal lobes. In Hindi, the plant is called amar bel (‘immortal vine’), presumably either referring to its vigorous growth, or to its healing properties.

This giant Asian dodder has completely enveloped a bush at Angkor Wat, Cambodia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this picture, taken early in the morning, it has enveloped a bush in Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This shrub of the genus Lindera, growing at Tharke Ghyang, Helambu, Nepal, has been enveloped by giant Asian dodder. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The small, bell-shaped flowers of giant Asian dodder, Marsyangdi Valley, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cynomorium coccineum

Formerly, this plant was regarded as belonging to the family Balanophoraceae (above), but genetic research indicates that it constitutes a separate family, Cynomoriaceae, where it is the only member. Previously, plants in Central Asia were regarded as a separate species, C. songaricum.

It is holoparasitic, living the major part of its life underground, where its rhizome is attached to the roots of various shrubs of the rockrose family (Cistaceae), the amaranth family (Amaranthaceae), the tamarisk family (Tamaricaceae), or the family Nitrariaceae. The fleshy top of the rhizome emerges in spring, with scale-like leaves, and a peculiar, erect, club-shaped, dark-red or purplish inflorescence, to 30 cm long, with numerous diminutive scarlet flowers, which are pollinated by flies, attracted by their sweet, slightly cabbage-like fragrance. The fruit is a small nut.

This species is distributed from the Mediterranean region eastwards across Arabia, the Middle East, and Central Asia to Mongolia and north-eastern China. It is quite rare, growing in rocky or sandy soils, in the Mediterranean area often near the coast.

It has been widely used in folk medicine throughout the distribution area. To some early herbalists, following the Doctrine of Signatures, the phallic shape of the inflorescence suggested that it could be used as a cure for impotence and other sexual problems, and its colour suggested that it could cure blood diseases. In Chinese medicine, it is used to treat kidney dysfunction.

Popular names include desert thumb and red thumb, and the name Maltese fungus was given due to its fungus-like appearance.

The generic name was the classical Latin term for broomrapes (Orobanche, see below), whereas it in the form kynomorion was the classical Greek word for dodders (Cuscuta, see above). The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘scarlet-coloured’.

Cynomorium coccineum, photographed in Zaranik Protected Area, Sinai, Egypt. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cytinaceae

A small family with about 12 species in 2 genera, Cytinus and Bdallophytum, which were previously included in the family Rafflesiaceae.

Cytinus

This genus contains about 8 species, found around the Mediterranean, eastwards to the Caucasus, and also in southern Africa and on Madagascar. They are parasites on plants of the genera Cistus, Halimium, and Ptilostemon.

The generic name was the classical Greek term for C. hypocistis, which was formerly used in herbal medicine for dysentery, throat tumors, and as an astringent. Young specimens of this plant may be eaten as a substitute for asparagus.

Cytinus ruber

This plant occurs around the Mediterranean, eastwards to the Caucasus. It is parasitic on Cretan rockrose (Cistus creticus) or other red-flowered rockroses. The corolla has 4 reddish, pink, or whitish petals, and the male flowers are situated in the centre of the inflorescence, whereas the female flowers are around the edge. They are pollinated by ants and beetles. The fruit is a berry.

Young plants are edible, and the species has been used in folk medicine for uterus and menstruation problems.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘red’, alluding to the main colour of the plant.

Young specimens of Cytinus ruber, near Vatos, Crete. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ericaceae Heath family

This huge family contains a few parasitic genera, which used to constitute a separate family, Monotropaceae. However, following genetic research, this family has now been reduced to a subfamily, Monotropoideae, in the heath family.

Allotropa virgata Candystick

This striking plant, the only member of the genus, is found in forests along the American Pacific coast, from California northwards to British Columbia, and also in Nevada, Idaho, and Montana, growing up to elevations around 3,000 m.

The red-and-white-striped flower stalk, which may sometimes grow to about 50 cm tall, has scale-like leaves. The inflorescence is a spike-like, terminal raceme with erect, white bracts, to 3 cm long. Sepals are usually missing, but 2-4 may sometimes be present, corolla cup-shaped, with 5 white, concave petals, stamens 10, maroon, protruding. The fruit is a capsule. The flower stalk remains standing long after the seeds have been dispersed, turning brown.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek allos (‘different’) and tropos (‘to turn’), alluding to the often upturned flowers. The specific name is derived from the Latin virga (‘staff’), referring to the straight flower stalk.

The popular names candystick, sugarstick, and barber’s pole all refer to its peculiar red-and-white-striped appearance, the latter name alluding to the poles with a helix of red and white stripes (in America also often blue), which used to signify a barber’s shop.

Candystick, Mount Rainier, Washington. Note the bluish-green caterpillar on the inflorescence. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Monotropa

This genus of 5 species is native to temperate areas of the Northern Hemisphere.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek monos (‘single’) and tropos (‘to turn’), referring to the flowers of pinesap (below), which all point in the same direction.

Monotropa hypopitys Pinesap

Also known as Dutchman’s pipe or yellow bird’s-nest, this plant is found throughout Europe, in northern Asia, southwards to the Himalaya and Thailand, and throughout North America, southwards to Mexico. It is parasitic on mycorrhiza of the genus Tricholoma.

A fleshy plant, to 35 cm tall. The only parts to emerge from the soil are the yellowish-white inflorescences, sometimes tinged with red, bracts scale-like, to 1 cm long, covering most of the flowers. The inflorescence is a raceme with up to 11 flowers, each to 1.2 cm long, all pointing in the same direction. They are pendulous when young, becoming erect when the seeds ripen.

There is some controversy regarding the specific name of this plant. Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) spelled the name hypopithys. In the Greek, hypo means ‘under’, whereas Pithys was the name of a wood nymph in Ancient Greek mythology, thus ‘under the nymph’. Linnaeus was known to be sometimes a bit of a prankster. Was he referring to the tangled root, which may resemble the tangled pubic hairs of a woman? Or did he simply misspell the name? Modern taxonomists spell the name hypopitys (without an h), where pitys (‘pine’) refers to one of the habitats of this species, as it often grows in dark pine forests.

The name yellow bird’s-nest alludes to the yellowish flowers and to the thick, tangled root, which somewhat resembles a bird’s nest. Naturally, the name Dutchman’s pipe refers to the flower shape.

Following recent genetic research, some scientists suggest that this species should be placed in a separate genus, named Hypopitys monotropa. (Source: M.I. Bidartondo & T.D. Bruns 2001. Extreme specificity in epiparasitic Monotropoidiae (Ericaceae): widespread phylogenetic and geographical structure. Molecular Ecology)

Pinesap, photographed on the island of Møn, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fruiting stage of pinesap, Byrums Sandfelt, Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Monotropa uniflora Ghost plant

This species differs from pinesap in being pure white, hence its popular name. Another name is Indian pipe, which, of course, refers to the flower shape. The specific name means ‘one-flowered’. As opposed to pinesap, each inflorescence of this species only has a single flower.

It is native to North and Central America, southwards to Columbia, and in eastern Asia, from the Himalaya eastwards to Sakhalin and Japan, and thence southwards to southern China and Taiwan. It grows in forests, being parasitic on mycorrhiza of the family Russulaceae.

This plant has been widely used in western herbal medicine to calm the nerves.

Ghost plant, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Tennessee, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ghost plant, Dasyueshan National Forest, central Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sarcodes sanguinea Snow plant

This striking, purely red plant, which derives its nutrients from underground fungi, is distributed in westernmost regions of North America, from the Cascade Range in Oregon southwards through montane areas of California and Nevada to the Mexican states Baja California, Baja California Sur, Sonora, and Sinaloa.

In his book The Yosemite (1912), Scottish-American writer and environmentalist John Muir (1838-1914) writes the following about this species: “The snow plant (…) is more admired by tourists than any other in California. It is red, fleshy, and watery and looks like a gigantic asparagus shoot. Soon after the snow is off the ground, it rises through the dead needles and humus in the pine and fir woods like a bright glowing pillar of fire. (…) It is said to grow up through the snow; on the contrary, it always waits until the ground is warm, though with other early flowers it is occasionally buried or half-buried for a day or two by spring storms. (…) Nevertheless, it is a singularly cold and unsympathetic plant. Everybody admires it as a wonderful curiosity, but nobody loves it as lilies, violets, roses, daisies are loved. Without fragrance, it stands beneath the pines and firs, lonely and silent, as if unacquainted with any other plant in the world; never moving in the wildest storms; rigid as if lifeless, though covered with beautiful rosy flowers.”

American botanist, chemist, and physician John Torrey (1796-1873) found the colour of this plant so striking that he named it Sarcodes sanguinea, from the Greek sarkos (‘flesh’) and the Latin sanguis (‘blood’), thus ‘the blood-coloured, fleshy one’. The common name refers to the early flowering of this species, which often appears, when snow is still partly covering the ground.

Snow plant, Siskiyou Mountains, Oregon. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

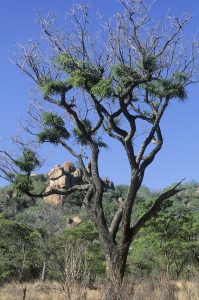

Loranthaceae Showy mistletoe family

Previously, a number of parasites on trees were all called mistletoes, placed in the family Viscaceae. However, extensive DNA research has caused this family to be abolished, and the vast majority has been moved to this family, which contains about 75 genera and 950 species. All are hemiparasites, with the exception of 3 terrestrial species, which are non-parasitic, and Tristerix aphylla (below), which is holoparasitic. Most species are found in tropical and subtropical regions.

As the family name implies, many species have beautiful, often brightly coloured flowers. The fruit is a berry, rarely a drupe or capsule. As in Santalaceae (below), the seeds are surrounded by a sticky substance, being spread by birds or, rarely, by small mammals.

This unidentified fruiting showy mistletoe was encountered near Upington, South Africa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Agelanthus

This is the largest genus of showy mistletoes in Africa, containing about 61 species. They are parasitic on various trees, including species of Combretum and acacias.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek agele (‘a group’) and anthos (‘flower’), alluding to the dense flower clusters in these plants.

Agelanthus zizyphifolius

This plant is distributed in drier forests of south-eastern Africa, from Kenya and eastern Zaire southwards to Botswana and Mozambique, at elevations between 500 and 2,200 m.

It is a bush with branches to 1 m long, leaves leathery, green or bluish-green, alternate, short-stalked, oblong, obovate, or elliptic, to 10 cm long and 4 cm wide, with 3-5 nerves. The remarkable flowers look like tiny pencils, clustered in the leaf axils, calyx tubular, to 5 mm long, corolla tubular, to 4.5 cm long, bright pink, with a narrow white or greenish constriction above, tip initially red, later white.

The specific name means ‘with leaves like Ziziphus‘, a genus of spiny shrubs and small trees in the buckthorn family (Rhamnaceae).

Agelanthus zizyphifolius, encountered at Lake Naivasha, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Oncocalyx

This genus contains about 12 species, distributed from Arabia and Sudan southwards through eastern Africa to South Africa, and also in Namibia and Angola.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek onkos (‘a bulb’ or ‘a swollen mass’) and kalyx (‘husk’), presumably referring to the flowers of these plants, which are swollen at the base.

Oncocalyx ugogensis

An East African species, distributed in Somalia, Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania.

A smooth plant, leaves alternate, clustered on short shoots, sessile, leathery, bluish-green, to 5 cm long and 3 cm wide, oblong, obovate, or elliptic, tip blunt or rounded, with a pair of lateral nerves. Flowers are solitary or up to 4 together in sessile, terminal umbels on short shoots, calyx tubular, to 6 mm long, with short lobes, corolla to 3.5 cm long, yellow or greenish-yellow, rarely red and yellow, tube to 1.5 cm long, swollen at the base, lobes extremely long, initially erect, later strongly reflexed. The fruit is an ovoid berry, to 7 mm long and 4 mm wide.

Oncocalyx ugogensis, observed at Lake Bogoria, northern Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Plicosepalus

A genus of about 12 species, found from Egypt, Jordan, and the Arabian Peninsula southwards through eastern Africa to South Africa, westwards to Chad, Angola, and Namibia.

The generic name is derived from the Latin plicatus (‘folded’), referring to the folds on the inner surface of the lower part of the sepals.

An unidentified species of Plicosepalus, Same, northern Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Plicosepalus curviflorus

The short-stalked leaves are clustered on short shoots, blade linear, oblong, or oblanceolate, to 7.5 cm long and 2 cm broad. Inflorescences are axillary umbels on short shoots, with 3-7 flowers, petals separate, to 3.5 cm long, basal part yellow or red, less often white or orange, S-shaped, with 4-5 paired folds inside, upper part normally red, sometimes yellow, recurved. Stamens red, anthers to 1.2 cm long. The fruit is an ellipsoid, smooth, red berry, to 1.2 cm long and 7 mm wide.

This species is widely distributed, from southern Egypt and the Arabian Peninsula southwards to eastern Zaire and Tanzania, primarily found in deserts or dry shrubland.

It is utilized in folk medicine to treat various diseases, including cancer, tonsillitis, and diabetes.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘having curved flowers’.

Plicosepalus curviflorus, growing on an acacia, Lake Baringo, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Psittacanthus Parrot-flower

These plants, comprising about 67 species, are found from Mexico through Central America to parts of South America. They differ from most other showy mistletoes by their large haustoria, flowers, and fruits. The flowers frequently “light up the host tree in brilliant hues of red or red and yellow.” (J. Kuijt 2009. Monograph of Psittacanthus (Loranthaceae). Systematic Botany Monographs, vol. 86, pp. 1-361)

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek psittakos (‘parrot’) and anthos (‘flower’), presumably referring to the gorgeous flower colours.

Psittacanthus ramiflorus

This gorgeous shrub grows in montane areas at altitudes between 1,000 and 2,500 m, mostly in humid forests. It is distributed from southern Mexico eastwards to Panama.

Branches many, to 1 m long, leaves short-stalked, elliptic, dull green, to 8 cm long and 4 cm wide, tip blunt, base continuing down the stalk. The inflorescences are dense clusters at the nodes, corolla tube swollen at the base, to 4 cm long, tapering towards the tip, red or orange on more than half of the length, yellow near the tip, flower stalk forming a cup-like structure at the base of the corolla. The fruit is a fleshy, bluish-black berry.

The specific name is derived from the Latin ramus (‘branch’) and flos (‘flower’), referring to the branched inflorescence.

Psittacanthus ramiflorus, Rincon de la Vieja National Park, Cordillera de Guanacaste, Costa Rica. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Scurrula

This genus, containing about 27 species, is found from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to China and Taiwan, and thence southwards through Indochina and the Philippines to Indonesia. The fruit is a berry.

The generic name may be derived from the Latin scurra (‘dandy’ or ‘jester’), perhaps alluding to the brightly coloured flowers.

An unidentified species of Scurrula, Rajaji National Park, Uttarakhand, northern India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Scurrula elata

A shrub, parasitic on broad-leaved trees, especially of the genera Quercus, Rhododendron, and Viburnum. Branches to 1.5 m long, brown, smooth, twigs covered in brown hairs. Leaves are ovate or oblong-ovate, opposite, smooth, leathery, pointed, to 15 cm long and 5 cm broad. Inflorescences are in axillary clusters with 6-10 flowers, corolla curved, red or orange at base, greenish or yellowish on upper half, to 3.5 cm long, with 4 reflexed lobes. The berry is yellowish, tapering, to 8 mm long and 5 mm broad.

This Himalayan plant is found from Himachal Pradesh, north-western India, eastwards to south-eastern Tibet, at elevations between 1,500 and 3,000 m. It is common in Nepal.

Ripe fruits are edible and sweet, and seeds can be chewed. A gluey substance was formerly extracted from the fruits and used as birdlime.

The specific name is Latin, having many meanings, here probably ‘lofty’, referring to its epiphytic way of growth.

Scurrula elata, growing on Rhododendron arboreum, Pati Bhanjyang, Helambu, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Scurrula elata, Tharke Ghyang, Helambu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Scurrula elata, growing on a species of Viburnum, Khumbu, eastern Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Scurrula elata with unripe fruits, Thodung Danda, Helambu, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tapinanthus

A genus with about 30 species, found from Mauritania eastwards to Sudan and the Arabian Peninsula, southwards through Africa to South Africa.

Some species, which were formerly placed in this genus, have been moved to other genera, including Agelanthus (above).

This picture probably shows a species of Tapinanthus, photographed at Spitzkoppe, Namibia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tristerix

This genus, comprising about 13 species, is native to the Andes, from Colombia southwards to Chile and Argentina. These plants are pollinated by hummingbirds and flowerpiercers (Diglossa), and the seeds are usually dispersed by various birds.

Tristerix aphyllus Cactus mistletoe

This bright red plant differs from other showy mistletoes in being holoparasitic. It is partial to two cactus species of central Chile, copao (Eulychnia acida) and quisco (Echinopsis chiloensis). Its seeds are dispersed by the Chilean mockingbird (Mimus thenca), which often deposits the seeds on the spines, where they sprout, the seedling growing up to 10 cm to reach the stem of the cactus. (Source: llifle.com/Encyclopedia/CACTI/Family/Cactaceae/7067/Eulychnia_acida)

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek a (‘without’) and phyllon (‘leaf’), alluding to the fact that this plant has no leaves.

Cactus mistletoe, growing on the trunk of a copao, Valle del Encanto, Ovalle (top), and on a quisco, south of Vallenar. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tristerix corymbosus

This gorgeous plant is restricted to the Andes in Chile and Argentina, found at elevations between 500 and 2,000 m. It is a generalist, being parasitic on at least 27 different plants in 13 families, mainly found in humid forests of southern beech (Nothofagus). Its seeds are not only dispersed by birds, but to a great extent by tiny marsupials of the genus Dromiciops.

The flowers are red or yellow, in dense clusters, and the leaves are fleshy, broadly ovate. The fruit is yellow or green at maturity.

The specific name is derived from the Latin corymbus (‘flower cluster’) and osus (‘numerous’).

Tristerix corymbosus, Reserva Nacional Altos de Lircay, Chile. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Misodendraceae

This family consists of a single genus, Misodendrum, popularly called feathery mistletoes, which are parasitic on various species of southern beech (Nothofagus). These plants, 8 species altogether, are restricted to South America.

The generic name is from the Greek misos (‘hatred’) and dendron (‘tree’), thus ‘hates trees’, referring to the parasitic habits of this genus. The common name refers to the feathery look of some species, especially M. linearifolium (below).

Misodendrum linearifolium

This shrub has a most peculiar appearance, resembling a huge, unkempt beard of an old man. As its specific name implies, the leaves are linear, to about 5 cm long. The branches grow to about 30 cm long.

It is distributed in central and southern Chile and south-western Argentina, southwards to Tierra del Fuego, found up to elevations around 300 m.

Previously, it was used medicinally, rubbed on sore muscles.

Misodendrum linearifolium, Reserva Nacional Altos de Lircay, Chile. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Misodendrum punctulatum

A small, much-branched shrub, to 25 cm high. The initial stem stops growing, and growth continues by lateral stems. Leaves are reduced to scales. Small flowers occur in spring in the leaf axils.

This plant is native to the southern half of Chile and adjacent areas of Argentina, growing up to elevations of about 2,000 m.

Misodendrum punctulatum, Conguillio National Park, Chile. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Moraceae Fig family

Ficus Fig trees

Certain members of this genus, called strangler figs, are not true parasites, as they do not possess haustoria. Instead, they begin their life as an epiphyte in a tree, the seed often sprouting in a pile of bird dung, delivered by the bird which ate the fig fruit.

Over the years, aerial roots of the young strangler fig grow down to the ground, where they take root, while other roots wrap themselves around the host tree, over time completely enveloping the tree, which is eventually strangled to death. As the trunk of the host tree decays, it leaves the fig tree as a hollow cylinder of aerial roots. Many strangler figs also readily grow on buildings.

Only 2 species are mentioned here. A large number of fig trees, including several strangler figs, are described on the page Plants: Fig trees.

This strangler fig in Bedugul Botanical Garden, Bali, Indonesia, stands alone, after its host tree has died. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

As the trunk of the host tree decays, it leaves the fig tree as a hollow cylinder of aerial roots, as in this picture from Ubud, Bali, Indonesia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ficus chirindensis

This strangler fig may grow into a massive tree, to 50 m tall, with numerous aerial roots. The leaves are spirally arranged, elliptic, oblong, or rounded, to 15 cm long and 7 cm wide, tip pointed, base heart-shaped, margin entire. Fruits to 4 cm across, greenish or pale yellow, with brown spots at maturity, in clusters up to 3 on short stalks on main branches.

It grows in montane evergreen forest at elevations between 700 and 1,600 m, from southern Kenya and eastern Zaire southwards through Tanzania, eastern Zimbabwe, and Malawi to Mozambique.

The specific name means ‘found in the Chirinda Forest’, a forest in eastern Zimbabwe. Presumably, the type specimen was collected there.

In this picture, I am standing inside a Ficus chirindensis, which has killed its host tree, leaving a hollow cylinder of aerial roots, Chirinda Forest, eastern Zimbabwe. (Photo Uffe Gjøl Sørensen, copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ficus tinctoria Dye fig, humped fig

A large evergreen strangler fig, to 25 m tall, with a spreading crown, and a trunk up to 3 m across. The short-stalked leaves are elliptic, ovate, or oblong, to 13 cm long and 6.5 cm wide, tip and base blunt-pointed or rounded, margin entire and often wavy. The fruits are globular, solitary or paired, very short-stalked, growing in the leaf axils, to 1.7 cm across. Initially they are green, later becoming yellow, orange, dull red, purple, or rusty-brown.

This species is found from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to southern China, and thence southwards through Indochina, Indonesia, the Philippines, and New Guinea to eastern Australia and many islands in the Pacific.

The fruits are edible and constitute as a major food source in Micronesia and Polynesia. Medicinally, a decoction of the leaves is used as a dressing for broken bones. Ropes are made from fibres of the bark.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘to dye’, alluding to the traditional usage of root and fruits to produce red and scarlet dyes.

This huge dye fig, subspecies gibbosa, envelops a Khmer ruin at Ta Prohm, Angkor Wat, Cambodia. Other pictures, depicting giant trees among these ruins, may be studied on the page Plants: Ancient and giant trees. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Orchidaceae Orchid family

Counting c. 880 genera and more than 22,000 species, orchids comprise one of the world’s largest plant families, found almost worldwide.

The flower structure of this family is unique. There are 3 sepals, often coloured and shaped like 2 of the 3 petals. The third petal forms the lower lip, usually differering very much from the other petals in size and shape, and sometimes in colour, often with a spur. Stamens and ovary are fused, forming the so-called column. Anthers and stigma are separated by a beak-like structure, the rostellum. The anthers produce so-called pollinia, small ‘bags’ which contain pollen. These pollinia easily stick to visiting insects by a sticky secrete, and the insects then transport them to the next flower where they get attached to the stigma. Other species are self-pollinating. The fruit is a capsule, containing countless tiny seeds, spread by the wind.

Most of these plants live in symbiosis with the mycelium of underground fungi, which is attached to the rhizome or root of the plants. When an orchid seed is about to germinate, it is completely dependent on this mycelium, as it has virtually no energy reserve, obtaining the necessary carbon from the fungus. Many orchids are dependent on the mycelium their entire life, but their relationship is symbiotic, as the orchid delivers crucial water and salts to the fungus. A few orchids, however, are parasitic on the fungus, as they do not possess chlorophyll, thus being unable to deliver nutrients to the fungus.

Corallorhiza Coralroot

A genus with about 12 species, all but one, the circumboreal common coralroot (C. trifida), restricted to North and Central America, and the Caribbean. These plants are entirely dependent on fungi to obtain nutrients, again with the exception of common coralroot, which contains some chlorophyll.

The generic and popular names allude to the entangled rhizomes of these plants, which resemble corals.

Corallorhiza maculata Spotted coralroot

This species is widespread, found from Canada southwards through most of the United States to Mexico and Guatemala, and also on some Caribbean islands.

Flowering stalk to 60 cm tall, yellowish-brown, reddish-brown, or reddish-purple, leaves reduced to yellowish, reddish, or dark purple sheaths. The inflorescence is a raceme with up to 40 flowers. The 3 sepals and 2 lateral petals are lanceolate, to 1.5 cm long, spreading or pointing forward, reddish, purplish, or yellowish-green, often with purple dots, lip obovate or elliptic, white with reddish-purple spots, to 9 mm long and 6 mm wide, with 2 tiny lateral lobes at the base. The column is pale yellow, with purple dots. Occasionally, plants with completely white or yellow flowers are encountered.

Dance-flies of the genus Empis have been reported as pollinators of this species.

Previously, several indigenous tribes made a decoction of the dried flower stalks to treat colds, pneumonia, and skin problems.

This plant is mentioned in a poem by American poet Robert Frost (see top of this page).

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘spotted’, alluding to the many purple spots on the flowers.

Spotted coralroot, Buttle Lake, Vancouver Island, Canada. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Corallorhiza mertensiana Pacific coralroot, Mertens’s coralroot

This plant is native to damp coniferous forests of western North America, from Alaska southwards to California, eastwards to Alberta, Montana, and Wyoming.

Flowering stalk to 65 cm tall, lavender-purple or reddish-purple, rarely yellow, leaves reduced to pale red, lavender-purple, or reddish-purple sheaths. The inflorescence is a raceme with up to 35 flowers. The sepals are reddish-purple, sometimes yellowish, lanceolate, to 1.2 cm long, the dorsal one and 2 petals arching over the column, nearly touching it. The 2 lateral sepals are widely spreading. Lip reddish-purple, white, or white with purple streaks or spots, to 1 cm long and 5 mm wide, usually with 2 tiny teeth on the margin. The column is pale yellow on the upper half, purplish or whitish near the base, curved.

The specific name was given in honour of German botanist Franz Carl Mertens (1764-1831), who undertook several scientific expeditions throughout Europe. He also published the third edition of Deutschlands flora, a five volume treatise on German flora, written by German botanist Johann Christoph Röhling (1757-1813).

Pacific coralroot, Kruse State Forest, California (top), and Mount Rainier, Washington State. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Neottia Nest orchid, twayblade

Formerly, this genus included only parasitic plants, but today, following genetic studies, it also includes members of the former genus Listera (twayblades). In its wider sense, the genus now contains about 80 species, native to cooler regions across most of Europe, northern Asia, and North America, with a few species extending into subtropical regions around the Mediterranean, in Indochina, and in the south-eastern United States.

The generic name is Ancient Greek, meaning ‘bird’s nest’, alluding to the appearance of the tangled roots of N. nidus-avis (below).

Neottia nidus-avis Bird’s-nest orchid

This species is distributed in the major part of Europe, eastwards to central Siberia, and also in north-western Africa, Turkey, Iran, and the Caucasus.

It is very easily identified by its brownish stem and flowers, entirely devoid of chlorophyll. The stem is to 40 cm, rarely 60 cm tall, with a terminal spike of up to 60 flowers. To germinate, the seeds are completely dependent on various species of fungi of the genus Sebacina.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘bird’s nest’, which, as the popular name, alludes to the thick, tangled root, which somewhat resembles a bird’s nest.

Bird’s-nest orchid is easily identified by its brownish inflorescence. This picture is from Kandersteg, Berner Oberland, Switzerland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bird’s-nest orchid, Dolomites, Italy. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Orobanchaceae Broomrape family

This family is huge, containing about 100 genera and more than 2,000 species, with members on all continents except Antarctica. With a few exceptions, all members are parasitic. Many genera are hemiparasites, which were formerly included in the figwort family (Scrophulariaceae), but, following extensive genetic research, they have been moved to the broomrape family.

Aeginetia

A small genus with about 7 species, distributed from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to Japan and Korea, and thence southwards through Indochina and the Philippines to Indonesia and New Guinea. According to Kew Gardens, there is also a single species in Cameroun, which is quite odd, considering the huge distance to the other species. It may belong to a separate genus.

The generic name honours Paulus Aegineta (c. 625-690), in English Paul of Aegina, a Byzantine, Greek-born physician, who wrote a medical encyclopedia in 7 volumes.

Aeginetia indica

This plant has no green parts, being parasitic on roots of various grass species, including bamboo, rice, maize, and sugarcane. Stem to 40, occasionally 50 cm tall, yellowish with thin, brown, vertical streaks, unbranched or branched from below, leaves usually absent, otherwise red, ovate-lanceolate or lanceolate, to 1 cm long and 4 mm wide, smooth. Flowers usually solitary, stalked, calyx to 4 cm long, pointed, yellowish or reddish with brown streaks, encircling the base of the corolla, which is purplish-red or violet, faintly dotted or streaked, tubular or bell-shaped, to 5 cm long and 2 cm wide, slightly curved. Anthers and stigma are yellow.

It is widely distributed, found from the Indian state of Uttarakhand eastwards to Korea and Japan, southwards to Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and New Guinea. In the Himalaya, it may be found up to elevations around 1,800 m.

In Nepal, root and flowers are used for treating infections and skin problems, in China for clearing away heat and toxins.

Aeginetia indica, Tamba Kosi Valley, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Aeginetia indica, Sagada, Luzon, Philippines. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bartsia alpina Alpine bartsia, alpine bells

Previously, the genus Bartsia contained 49 species, 45 of which are endemic to the Andes. Recent genetic studies, however, have led to a revision of the genus, placing most species in a new genus, Neobartsia, leaving only this species in Bartsia.

The genus was named in honour of a Prussian botanist, Johann Bartsch (1709-1738) of Königsberg. The famous Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) urged him to participate in an expedition to present-day Suriname as a physician, but, unfortunately, he perished during this journey.

Alpine bartsia is easily identified by its dark purple inflorescence, an adaptation to repel harmful UV-radiation. It is a prostrate plant, often branched from below, stems erect or ascending, hairy, to 30 cm tall. Leaves opposite, ovate, very hairy, to 2.5 cm long, toothed along the margin. The lower leaves are green, those above are tinged with purple. The dark purple corolla is narrow at the base, to about 2 cm long, 2-lipped, a hood-like upper lip and a shorter lower one with 3 blunt lobes.

This plant is distributed in subarctic areas, from Scandinavia eastwards to central Siberia, and also in Iceland, Greenland, and north-eastern Canada. In southern Europe, it is restricted to mountains, found in the Pyrenees, the Alps, mountains of eastern Europe, and on the Balkans. Populations in the Black Forest and the Vosges, and on the Swedish island of Gotland, are regarded as ice-age relics.

Alpine bartsia is common in the Alps. This picture shows a large population in Cabane de Prarochet, Col du Sanetsch, Valais, Switzerland. A leaf rosette of dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) is seen in front. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Alpine bartsia, Turracher Höhe, Austria. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bellardia trixago Mediterranean lineseed

This hemiparasite, the only member of the genus, is native around the Mediterranean, eastwards to the Caucasus and Iran, and thence southwards to Yemen and Kenya, and also on the Azores, Madeira, and the Canary Islands, with an isolated occurrence in South Africa. It has been introduced to western and southern United States and several South American countries, and is regarded as an invasive in some areas. It grows in a variety of habitats, including shrubberies, fields, maquis, open slopes, meadows, and sandy areas, from sea level to elevations around 1,200 m.

Stem erect, usually simple, to 70 cm tall, glandular-hairy above, leaves glandular-hairy, linear or oblong, to 9 cm long, sessile, margin strongly toothed or pinnately divided. The inflorescence is terminal, bracts leaf-like, heart-shaped, pointed, longer than the calyx, which is to 1.2 cm long, upper lip of corolla pink or purple, smaller than the lower lip, which is white or yellow, 3-lobed, to 2.3 cm long, tube to 1.7 cm long.

The generic name was given in honour of Italian physician and botanist Carlo Antonio Lodovico Bellardi (1741-1826), professor at the University of Turin.

The meaning of the specific name is obscure. It may stem from Ancient Greek thrix (‘hair’), alluding to the plant being glandular-hairy, or from Ancient Greek trixos (‘triple’), referring to the lower lip having 3 lobes.

Mediterranean lineseed, near Kandira, Black Sea (top), and Boz Dağlari, east of Manisa, both in Turkey. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Boschniakia, see Kopsiopsis.

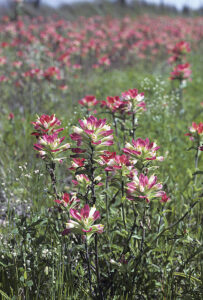

Castilleja Indian paintbrush

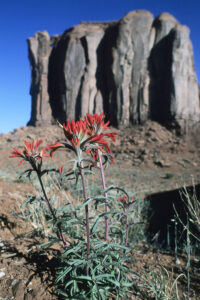

Most members of this genus, comprising about 200 species, have brilliant red bracts, giving rise to their popular names Indian paintbrush and prairie-fire. The flowers of a few species are orange, yellow, or violet.

These plants are native to the western parts of the Americas, from Alaska southwards to the Andes, with one species, C. pallida, distributed across Siberia, westwards to the Kola Peninsula, and southwards to the Altai Mountains.

The flowers of some species are edible and were formerly consumed by various native tribes, but as these plants tend to absorb and concentrate selenium in their tissue, roots and green parts can be very toxic.

The generic name was given in honour of Spanish surgeon and professor of botany Domingo Castillejo Muñoz (1744-1793).

An unidentified Castilleja species, Yosemite National Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Castilleja affinis Coast paintbrush

Stem erect or ascending, to 60 cm tall, more or less hairy, leaves linear or lanceolate, green or purplish, sometimes reddish-brown, to 13 cm long, with up to 5 spreading, linear or lanceolate lobes, margin often wavy. Inflorescence to 30 cm long, bracts green or dark purple near the base, otherwise bright red, pink, orange, purplish, or yellow, with up to 7 narrow lobes. Corolla tubular, straight or curved, to 4 cm long, lower lip dark green, reddish, brown, or dark purple.

This plant is native to the Pacific States, from Washington southwards to Baja California, growing on slopes along the coast, and also a little inland.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘related to’, presumably referring to another member of the genus.

Coast paintbrush, Torrey Pines State Beach, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Coast paintbrush, Ronald W. Caspers Wilderness Park, Santa Ana Mountains, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Castilleja chromosa Desert paintbrush

This plant, also called C. angustifolia, is much like the previous species, but leaves are greyish-green or bluish-green, to 7 cm long, strongly lobed. It is quite common in arid areas, from the Pacific States eastwards to Wyoming and Colorado, and from northern Idaho southwards to the Mexican border.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek khroma (‘colour’), thus ‘(strongly) coloured’.

In this picture, desert paintbrush grows in a barren area in front of a natural bridge, named Owachomo Bridge, which spans the White River, Natural Bridges National Monument, Utah. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Desert paintbrush, Monument Valley, Arizona. The striking rock in the background is called Elephant Butte. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Castilleja exserta Purple owl’s clover

Previously, this plant, also called red owl’s clover, was placed in the genus Orthocarpus, named O. purpurascens. It is easily identified by bracts and flowers usually being bright purplish-violet, although they may also be lavender, magenta, pale purple, or white. The specific name refers to the protruding stigma.

It is native to California, Arizona, New Mexico, and north-western Mexico.

In former days, indigenous peoples of California harvested the seeds for food.

This species is crucial as a host plant for a threatened subspecies of the Bay checkerspot butterfly (Euphydryas editha ssp. bayensis), of the family Nymphalidae, which is endemic to the San Francisco Bay area.

Purple owl’s clover, Mazatzal Mountains, Arizona. The white flower is Arizona mariposa tulip (Calochortus ambiguus). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Purple owl’s clover, Lake Saguaro, Arizona. Note the protruding stigmas. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Castilleja indivisa Texas paintbrush, entire-leaved paintbrush

A highly variable species, growing to 45 cm tall, with green, entire, linear leaves, bracts varying from bright red to reddish-purple or pinkish, calyx hairy, pale green near the base, white or rosy near the tip, surrounding the corolla, of which only the tip of the beak and the stigma are protruding.

This plant is restricted to Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘undivided’, alluding to the entire leaves (as opposed to most other members of the genus, which have strongly lobed leaves).

Texas paintbrush, Gilchrist, Texas. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Castilleja lanata Sierra woolly paintbrush

A tall plant, to 90 cm high, leaves pale grey or greyish-brown, standing at an angle at around 90 degrees to the stem, and often with upturned margin. The greenish-yellow corolla is tubular, to 4 cm long, tapering towards the tip.

A widely distributed plant, found from California eastwards across Arizona and New Mexico to Texas, growing in rocky areas and shrubberies.

The specific name is derived from the Latin lana (‘wool’), alluding to the woolly hairs covering stem and leaves.

Woolly paintbrush, Pinnacles National Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Castilleja latifolia Monterey paintbrush

This plant is restricted to a small area along the Californian Pacific Coast, from San Francisco Bay southwards to Monterey, where it grows in coastal shrub and on sand dunes. The bracts are usually red with a green base, but a form with yellow and green bracts is sometimes seen. It may be identified by the broad, entire leaves, which gave rise to the specific name, Latin for ‘broad-leaved’.

Monterey paintbrush, Garrapata State Park, south of Monterey, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A form of Monterey paintbrush with yellow bracts, observed in Andrew Molera State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cistanche

This genus, comprising about 24 species, is indigenous to northern and eastern Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and from southern Europe eastwards across the Middle East and Central Asia to northern China, and thence southwards to India and southern China.

Two species, C. deserticola and C. salsa, in Chinese 肉苁蓉 (rou cong rong), constitute an important ingredient in Chinese herbal medicine. The former is grossly over-collected and has become rare, partly due to loss of its host, Haloxylon ammodendron, which is widely used for firewood. (Source: urbol.com/cistanche-tubulosa-and-deserticola)

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kistos (‘rockrose’) and ankhein (‘to strangle’), referring to some species being parasitic on rockroses, genus Cistus.

Cistanche phelypaea

This plant is parasitic on roots of various bushes, growing in sandy areas. Stem fleshy, to 50 cm tall, leaves pale brown, ovate or lanceolate, smooth. The inflorescence is a terminal, cylindrical, dense spike, corolla bell-shaped, strongly curved, smooth, bright yellow or sometimes pale purple, with 5 broad, reflexed lobes.

It is native to the Iberian Peninsula, Italy, northern Africa, Somalia, the Arabian Peninsula, Jordan, Syria, and Cyprus.

The plant may be eaten similar to asparagus. It is used medicinally in Somalia for diarrhoea and menstrual disorders.

The specific name was given in honour of French politician Louis Phélypeaux (1643-1727), Marquis of Phélypeaux (1667), Count of Maurepas (1687), and Count of Pontchartrain (1699).

Cistanche phelypaea, growing on roots of Tetraena alba (formerly called Zygophyllum album), a shrub of the family Zygophyllaceae, Zaranik Protected Area, Sinai, Egypt. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cistanche tubulosa Desert broomrape

Stem to 40 cm tall, yellowish-brown or purplish, with small scale-like leaves. The inflorescence is a broad spike, to 30 cm long and 9 cm across, bracts often purplish, corolla various shades of yellow, to 5 cm long, erect at first, later curved forwards, with 5 broad, entire, reflexed lobes, which are sometimes mauve along the margin.

As its popular name implies, this species is found in deserts, from northern and eastern Africa eastwards to India and Kazakhstan. Favourite hosts include bushes of the genera Salvadora, Haloxylon, Zygophyllum, and Cornulaca.

In Chinese medicine, it is sometimes used as a substitute for C. deserticola.

The specific name is a diminutive of the Latin tubus (‘pipe’ or ‘tube’) and osus (‘numerous’), alluding to the numerous tubular flowers.

Desert broomrape, Buffalo Springs National Park, Kenya. The small blue flowers in the foreground are Blepharis linariifolia, of the acanthus family (Acanthaceae). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Conopholis Squawroot

A small genus with 3 members, found from eastern Canada southwards to Florida, and from south-western United States southwards to Panama.

The generic is derived from Ancient Greek konos (‘cone’) and pholis (‘scale’), presumably referring to the general appearance of the plant when in fruit.

Conopholis alpina Alpine squawroot

This plant, sometimes called alpine cancer-root, is native from south-western United States (Texas, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona) southwards to Honduras, growing at elevations between 1,500 and 2,800 m. Despite the latter name, there is no evidence that it contains any anti-cancer properties.

The entire plant is bright yellow, yellowish-white, or cream-coloured, stem occasionally to 33 cm tall, but usually much lower, bracts triangular or narrowly lanceolate, to 2.2 cm long and 9 mm wide, often brown-tipped, glandular-hairy, corolla tubular, to 2 cm long, 2-lipped.

A variety of this species, var. mexicana, called Mexican squawroot, is parasitic on roots of various species of pine (Pinus) and oak (Quercus). It was formerly used by indigenous tribes against tuberculosis.

Mexican squawroot, Lake Powell, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cycnium

This genus, contaning about 17 species, is indigenous to sub-Saharan Africa and Madagascar. These plants are usually parasitic on grass roots. The flowers are showy, resembling Phlox flowers.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kyknos (‘swan’), probably likening the slender, elongated corolla tube to a swan’s neck.

Unidentified species of Cycnium, possibly tubulosum, Kalasa Mukoso, northern Zambia (top), and Sao Hills, western Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cycnium tubulosum

A very variable plant, stem smooth, angular, from almost absent to 60 cm tall, erect, ascending, or creeping, leaves few, linear, entire, pointed, to 8 cm long and 1 cm broad, flowers axillary, stalked, to 3.2 cm long, sepals 5, fused, forming a bell-shaped tube, to 1.3 cm long, ending in 5 lanceolate, keeled lobes, to 8 mm long, corolla white, pinkish, or purple, with 5 fused petals, forming a curved, cylindrical tube, to 2.8 cm long, ending in a flat disk, to 4.2 cm across, with 5 ovate lobes.

It is distributed in the major part of Africa south of the Sahara, and also on Madagascar, growing from the lowlands up to elevations around 1,600 m.

The specific name is a diminutive of the Latin tubus (‘pipe’ or ‘tube’) and osus (‘numerous’), alluding to the tubular flowers.

This picture from Lake Bogoria, Kenya, probably shows Cycnium tubulosum. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Epifagus virginiana Beech-drops

This species, the sole member of the genus, is distributed in the eastern half of North America, from Hudson Bay southwards to Texas and Florida, and also in north-eastern Mexico.

In her book Nature’s Garden: An Aid to Knowledge of Our Wild Flowers and Their Insect Visitors (1900), American historian and nature writer Neltje Blanchan de Graff Doubleday (1865-1918) gives this characteristic of beech-drops: “Nearly related to the broom-rape is this less attractive pirate, a taller, brownish-purple plant, with a disagreeable odor, whose erect, branching stem without leaves is still furnished with brownish scales, the remains of what were once green leaves in virtuous ancestors, no doubt. But perhaps even these relics of honesty may one day disappear.”

It produces many brown stems, to 30 cm tall, bearing small, white and purple flowers.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek epi (‘on’) and the Latin Fagus, the generic name of beeches, alluding to the plant being parasitic on roots of American beech (Fagus grandifolia).

Beech-drops, encountered in Blydenburgh County Park, Long Island, New York. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Euphrasia Eyebright

This genus, comprising about 200 species, is widely distributed, with the exception of large parts of Africa, Madagascar, Arabia, Tropical Asia, and the Americas. Most species are very similar and difficult to distinguish.

The generic name is derived from Euphrosyne (’gladness’), the name of one of the three graces of Ancient Greece, who was known for her joy and mirth. The name was probably given to the plants because of their properties as medical herbs.

The usage of eyebright for eye problems goes back to medieval Europe. Followers of the Doctrine of Signatures claimed that the Great God had made all plants, so that humans would recognize the usage of them. To them, the red streaks on the petals of eyebright resembled bloodshot eyes, and for this reason, these plants would be an effective remedy for eye diseases.

Matthaeus Sylvaticus (1285-1342), a physician of Mantua, recommended them for disorders of the eyes, whereas Jervis Markham (1568?-1637), in his Countrie Farm (1616), advises people to “drinke everie morning a small draught of eyebright wine.” In the 18th Century, eyebright tea was drunk, and in Queen Elizabeth’s time a drink called ‘eyebright ale’ was produced.

English herbalist John Gerard (c. 1545-1612) says that powdered eyebright, mixed with mace, “comforteth the memorie,” and another herbalist, Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654), recommends the following recipe for “an excellent water to clear the sight: Take of fennel, eyebright, roses, celandine, vervain, and rue, of each a handful, the liver of a goat chopt small, infuse them well in eyebright water, then distil them in an alembic, and you shall have a water will clear the sight beyond comparison.”

For once, the followers of the Doctrine of Signatures hit the nail on the head, as these plants are still recommended for conjunctivitis (‘red eyes’), infection of the eyelid, and discharge from the eyes. They are also used for indigestion, and for inflammation of the trachea. The dried herb is an ingredient in British Herbal Tobacco, which, when smoked, is useful for treatment of chronic bronchial colds.

A popular French name of these plants is casse-lunettes, which loosely translates as ‘throw away your glasses’.

This unidentified eyebright was encountered in Lahaul, Himachal Pradesh, northern India. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Another unidentified eyebright, near Ibon de Piedrafita, Spanish Pyrenees. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ghikaea speciosa

This pretty plant, the sole member of the genus, is distributed in dry habitats of south-eastern Ethiopia, Somalia, and northern Kenya.

Stem to 3 m tall, rough, leaves ovate, to 4 cm long and 1.6 cm wide, blunt or pointed, margin entire, flowers stalked, calyx to 1.3 cm long, divided about halfway into triangular lobes, corolla to 4 cm long, pink, purple, or rose-coloured, broadly bell-shaped, widened towards the mouth, with 5 reflexed lobes.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘showy’.

Ghikaea speciosa, Shaba National Park, northern Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kopsiopsis Ground-cone

A small genus with only 2 species, native along the North American Pacific coast, from British Columbia southwards to north-western Mexico. They were previously placed in the genus Boschniakia.

The part above ground is a very compact cone-shaped cluster of flowers, which gave rise to the popular name. The flower colour may be yellow, red, brown, or purple.

The generic name is Latin, meaning ‘resembling Kopsia‘. This does not relate to the modern genus Kopsia, which includes showy members of the dogbane family (Apocynaceae), but to Orobanche ramosa (see below), which was originally named Kopsia ramosa. This name was given in honour of a Dutchman, Jan Kops (1765-1849), who worked as priest, botanist, agronomist, professor, and publisher. It seems that he was an extremely busy man, having 11 children with his first wife and 6 with his second.

Kopsiopsis hookeri Small ground-cone, Hooker’s ground-cone

This species, previously known as Boschniakia hookeri, is distributed in forests, from British Columbia southwards to northern California. It is parasitic on roots of salal (Gaultheria shallon), occasionally on Pacific madrone (Arbutus menziesii), bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), and blueberry species (Vaccinium).

The part visible above ground is a flower stalk, to 16 cm tall, with scale-like leaves, to 1.2 cm long. The inflorescence is a cone-shaped, very dense raceme, to 7 cm long, with large erect bracts, to 1 cm long and broad, corolla reddish, pink, purplish, brownish, pale yellow, or whitish, to 1.5 cm long, upper and lower lips to 4 mm long.

In former days, coastal tribes ate the base of the flower stalk raw.

The specific name honours British botanist William Jackson Hooker (1785-1865), who became the first director of the famous Kew Gardens in London in 1841. Here, he founded the herbarium and enlarged the gardens and the arboretum.

White-flowered form of small ground-cone, Crest Mountain Trail, Vancouver Island, Canada. The lower picture with withered flowers gives a clear impression of the reason for the common name ground-cone. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lathraea Toothwort

This small genus contains 5 species, native to the entire Europe, except Iceland, eastwards to Russia, southwards to the Mediterranean, Turkey, and northern Iran, and also in the Himalaya, China, Korea, and Japan

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek lathraios (’clandestine’), alluding to the fact that the entire plant is hidden underground, except when it is flowering. Its whitish underground stem is covered in thick, fleshy leaves with rows of tooth-like scales, giving rise to the popular name of the genus.

Lathraea squamaria Common toothwort

This species is distributed in almost all of Europe, and in Turkey, the Caucasus, and northern Iran, with an isolated population in the Himalaya, which may very well be a separate species.

Flowering stem erect, to 30 cm tall, juicy, smooth, glandular-hairy, white or yellowish below, pinkish above, leaves scaly, fleshy, ovate or rhombic, to 1 cm long and 8 mm wide, bracts broad, leaf-like, inflorescence a one-sided spike, calyx bell-shaped, pink, to 1.2 cm long, glandular-hairy, corolla tubular, to 1.7 cm long, with 2 lips, upper pink, entire, boat-shaped, with keel, lower 3-lobed, whitish.

It is parasitic on roots of hazel (Corylus), occasionally on elm (Ulmus), ash (Fraxinus), alder (Alnus), walnut (Juglans), and beech (Fagus).

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘scaly’, referring to the scale-like subterranean leaves.

Common toothwort may bloom as early as March, when snow occasionally covers the ground. This picture is from near Aarhus, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Melampyrum Cow-wheat

This genus, comprising about 38 species, is distributed in subarctic and temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere, in Eurasia southwards to the Mediterranean, Iran, and China, in America to Idaho and Georgia.

The generic name is derived from the Greek melas (‘black’) and pyros (‘wheat’), alluding to the black seeds, which somewhat resemble wheat grains. An ancient belief has it that the seeds, when mixed with wheat and ground into flour, tend to make the bread black. In the Middle Ages, it was also believed that the seeds were capable of being converted into wheat, supposedly because of the sudden appearance of these plants among wheat, planted on recently cleared land. Cows and sheep readily eat these plants, hence the name cow-wheat. (Source: M. Grieve 1931. A Modern Herbal. Jonathan Cape)

In his Cruydeboeck (‘Herbal Book’), Flemish physician and botanist Rembert Dodoens (1517-1585) tells us that “the seeds of this herb taken in meate or drinke troubleth the braynes, causing headache and drunkennesse.”

Melampyrum arvense Field cow-wheat

Stem erect, to 60 cm tall, usually branched, leaves opposite, almost stalkless, linear or narrowly elliptic, upper ones with many narrow teeth at the base. The inflorescence is a terminal spike, to 10 cm long, lower bracts green, resembling the leaves, but with longer teeth, upper bracts bright purplish-red, lanceolate or narrowly ovate, with many teeth, to 8 mm long, corolla 2-lipped, to 2.5 cm long, purplish-red at base and tip, white or yellow on the middle part.

This species is distributed almost throughout Europe, southwards to the Mediterranean, eastwards to the Ural Mountains and Kazakhstan. In Central Asia, it grows in grasslands.

The specific name is derived from the Latin arvus (‘cultivated’), thus ‘growing in cultivated fields’. Previously, it was a troublesome weed in corn fields, as its seeds contain the toxic aucubin. Today, however, it has become rare due to more effective treatment of crop seeds.

Field cow-wheat, photographed on the island of Gotland, Sweden (upper two), and on Røsnæs Peninsula, north-western Zealand, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Melampyrum nemorosum Wood cow-wheat

This species is distributed from Denmark and Sweden eastwards to western Siberia, southwards to the Mediterranean and Ukraine. It is quite common in eastern Europe.

Stem to 40 cm tall, branched, soft-haired, leaves opposite, short-stalked, lanceolate or ovate, upper ones toothed at the base. The lower flowers are in pairs from the leaf axils, upper ones in a one-sided, terminal spike, surrounded by crowded bracts, purplish-blue or violet, rarely yellowish-white, sepals fused, calyx bell-shaped, woolly-hairy, 4-lobed, corolla to 2 cm long, bright yellow, tubular, curved, 2-lipped, upper lip hooded, lower 3-lobed.

The specific name means ‘growing in woods’, originally derived from Ancient Greek nemos (‘a clearing in the forest’). Popular names include the Swedish natt-och-dag (‘night-and-day’) and the Russian Ivan-da-Marya (‘Ivan and Maria’), both names referring to its striking inflorescence with yellow flowers and bright purplish-blue or violet bracts.

Large growth of wood cow-wheat, Småland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wood cow-wheat, growing along a hedge near Halltorps Hage, Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wood cow-wheat, Laelatu Nature Reserve, Estonia. Note that the bracts are quite different from those of the Swedish plants above. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Melampyrum pratense Common cow-wheat

This species is found in all of Europe, eastwards to central Siberia, all the way north to the Arctic coast, growing in open forests and shrubberies, and in moorlands, on acidic soils.

Plant to about 40 cm tall, often branched, leaves opposite, almost stalkless, linear or narrowly lanceolate, green or occasionally purple, to 10 cm long. The inflorescence is a terminal, one-sided, lax spike, lower bracts like the leaves, but smaller, upper usually toothed or with long, narrow lobes, calyx with fused sepals, with 4 lobes to 5 mm long, corolla pale or dark yellow, sometimes reddish, to 1.8 cm long, 2-lipped, upper lip forming a hood, lower straight, 3-lobed. The seeds are dispersed by ants of the genus Formica, which eat a fleshy structure on the seed, called elaiosomes.

This species is readily eaten by cows, giving rise to the common name of the genus. It contains large quantities of dulcit, a saccharide, and the fact that it also contains a toxic glycoside, rhinanthin, did not seem to harm the cattle.

In former days, it was utilized in traditional Austrian medicine, taken internally as tea, or used externally as filling in pillows to treat rheumatism and blood vessels calcification.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘growing in meadows’ – not a descriptive name, as the plant mostly grows in forests and moorland.

In Sweden, common cow-wheat is extremely common. These pictures are from a pine forest near Friseboda, Skåne. The lower picture shows a plant, which has rooted among reindeer lichens (Cladonia). (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Common cow-wheat, Grimstrup Krat, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Common cow-wheat, a form with purple bracts and reddish flowers, Lake Salten, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Melampyrum sylvaticum Small cow-wheat

This plant resembles common cow-wheat (above), but is smaller, with smaller, golden-yellow flowers. It is partial to coniferous forests, growing all over Europe, including Iceland, eastwards to western Siberia, southwards to the Mediterranean.

The specific name means ‘growing in woods’, derived from the Latin silva (‘forest’).

Small cow-wheat is quite common in the Alps, here photographed in the Stubai Valley, Austria. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Odontites Red bartsia, false bartsia

This genus, numbering about 37 species, is distributed in all of Europe, except Iceland, and in north-western Africa, the Middle East, and northern Asia, southwards to Iran and northern China. Formerly, these plants were included in the genus Bartsia (above), which is the reason for their popular names.

The generic name means ‘tooth-related’, derived from Ancient Greek odous (‘tooth’). According to Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder (23-79 A.D.), plants of this genus were used to treat toothache.

Odontites litoralis Salt bartsia

This plant resembles the red bartsia (see description below), but as its name implies, it always grows near the coast, preferably on littoral meadows, but sometimes on rocks. It has a limited distribution, from Norway and Finland southwards to England, Holland, Germany, and Poland.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘of seashores’.

Salt bartsia, growing in a littoral meadow on the island of Fanø, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Odontites vulgaris Red bartsia

Stem to 50 cm tall, angular, downy, reddish, usually much-branched from below, branches 2-12, ascending, leaves opposite, lanceolate, to 5 cm long and 1 cm wide, tip blunt, margin with 3-5 teeth. Inflorescences are rather lax racemes, growing from the leaf axils, each with up to 10 flowers, to 1 cm long, bracts like the leaves, but much shorter, to 1.5 cm long and 4 mm wide, calyx broadly bell-shaped, green or purple, hairy, to 6 mm long, with 4 rather large lobes, corolla tubular, pink, rose-coloured, or whitish, hairy, 2-lipped, upper lip down-curved, notched, lower 3-lobed.

It is widely distributed, found in all of Europe, except Iceland, eastwards to eastern Siberia, southwards to the Mediterranean, Iran, and northern China.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘common’.

Red bartsia, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Orobanche Broomrape

A genus with about 200 species, distributed on all continents, except Antarctica, with a majority in temperate areas of the Northern Hemisphere.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek orobos (‘bean’) and ankhein (‘to strangle’), alluding to the bean broomrape (O. crenata, below).

Orobanche alba Thyme broomrape

As its popular name implies, this species is partial to thyme (Thymus), but may occasionally grow on species of oregano (Origanum) and savory (Satureja). The stem is reddish or yellow, erect, to 25 cm tall, leaves and bracts dark purple, scale-like, flowers in a terminal, open spike, corolla tubular, to 2.2 cm long, glandular-hairy, whitish, reddish, or yellowish with numerous violet or purple streaks, especially towards the tip.

It has a wide distribution, occurring in the major part of Europe and in North Africa, eastwards through Russia and south-western Asia to Tibet, the Himalaya, and central China. In the Alps, it is found up to altitudes of about 1,900 m, whereas in Asia it has been encountered up to 3,700 m. It prefers moderately dry, calcareous soils.

Thyme broomrape, Lake Gosau, Austria. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Orobanche anatolica Anatolian broomrape

Stem to 35 cm tall, thick, densely hairy. Spike many-flowered, usually very dense, bracts same length as flowers, or longer, hairy, calyx with broad, pointed teeth, glandular-hairy, with 3-5 thick veins, corolla densely glandular-hairy, colour variable, reddish-brown, yellow, or ginger-orange, lower lip with 2 red bumps, upper lip curved and helmet-shaped.

This plant is found from Turkey and the Caucasus southwards to Syria, northern Iraq, and northern Iran, growing exclusively on species of sage (Salvia), at elevations between 400 and 2,500 m.

The specific name refers to Anatolia, the Asian part of Turkey.

Anatolian broomrape is rather common in central Turkey, here observed near Bulanik, south of Çay. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Orobanche crenata Bean broomrape

This species is native around the Mediterranean, and thence across Turkey, Jordan, and Iraq to the Caucasus and Iran, and also on the Azores, Madeira, and the Canary Islands. It is a common parasite on the fava bean (Vicia faba), but may also grow on various other plants, from sea level to elevations around 800 m.

Stem stout, to 80 cm tall, spike many-flowered, bracts narrowly lanceolate, long-pointed, glandular-hairy, brown or purplish about the same length as the corolla tube. Calyx lobes 2, separated, each with 2 narrow, divergent teeth. Corolla to 3 cm long, white or pale lilac, or a combination, often with many darker violet, longitudunal streaks, orange-yellow in the throat, lips having broad lobes, which have rounded teeth along the wavy margin.

In Apulia, southern Italy, its stems, called sporchia, are eaten. (Source: E. Luard 2004. European peasant cookery, Grub Street)

The specific name is Latin, in a botanical context meaning ‘with blunt teeth along the margin’, in this case referring to the corolla tube.

Bean broomrape, growing on an umbellifer among boulders along the sea front, Sultanahmet, Istanbul, Turkey. The plant in the background is spreading pellitory-of-the-wall (Parietaria judaica). (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Orobanche elatior Knapweed broomrape

This large species, which may grow to 70 cm tall, is partial to greater knapweed (Centaurea scabiosa), but is occasionally found on other species of knapweed, and also rarely on other members of the daisy family (Asteraceae) and on members of the buttercup family (Ranunculaceae).

Plant reddish or yellowish-brown, or a combination, usually glandular-hairy, leaves scale-like, narrowly lanceolate, to 2 cm long and 4 mm wide. The inflorescence is a terminal spike, to 15 cm long, bracts lanceolate, as long as the flowers, which are up to 2.5 cm long, yellowish-brown or purplish-red, curved, upper lip toothed, stigma yellow.

It grows in open areas, only on alkaline soils, found in the major part of Europe, eastwards through western and Central Asia to the Gansu Province of China, southwards to the Mediterranean and Iran.