Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Tanzania 1988: Experiencing African bureaucracy

Our planning has been made in co-operation with the Tanzanian section of ICBP, and an important aspect of the trip is to include Tanzanian participants in the expedition, during which we will do our best to make them interested in birds, so that they may later become keen birdwatchers and conservationists.

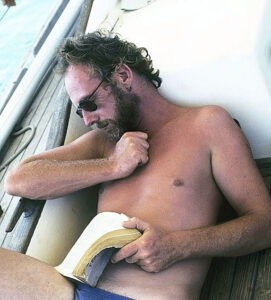

Transportation along the coast is going to take place on board a rented sailboat, the Gaia Quest, a 12-metre-long ketch, owned by Englishman Richard Speir. Besides Captain Speir, the boat is manned by First Mate Neil Murray, who is also English, and a cook, Siobhan Bigger, who is Irish.

The counts are going to be made from the seaside, and we shall motor ashore on selected localities in a rubber dinghy, fitted with an outboard engine.

Meanwhile, our two Tanzanian participants, Bruno Mvula and Paschal Nguye, have arrived. Our fourth Danish member, Ole Thorup, arrives at the last moment, and as our research period is limited to a month, we don’t have time to get him registered as one of the participating ‘scientists’. As it later turns out, this is a serious mistake.

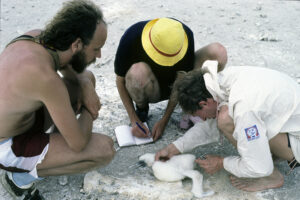

While waiting for the permits, we count birds along the coast north of Dar, and we also make a two-day trip to Latham Island, an offshore island about 70 km from the coast, which houses large seabird colonies of sooty tern (Onychoprion fuscatus), brown noddy (Anous stolidus), and masked booby (Sula dactylatra).

After returning to Dar, the brand-new outboard engine for our dinghy is stolen the following night, which delays us another couple of days.

The coast here contains various habitats, including sandy beaches; flat rocks, consisting of fossilized coral, which are submerged during high tide; river deltas; mangroves; and low, coastal forests, situated inland behind the mangroves, and along river banks.

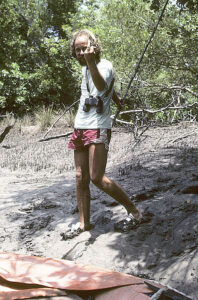

As a rule, Neil brings us ashore in the dinghy, where we make our counts on foot, often walking several kilometres, sometimes in soft mud. In Kisigese Forest Reserve, we observe two female Tanzanian black-and-white colobus (Colobus angolensis ssp. palliatus) with young, and we find feathers of the rare Kenya crested guineafowl (Guttera pucherani).

One day, when we have all left Gaia to go ashore, we almost get a heart attack. A sudden gale causes the anchor chain to snap, and the boat drifts towards the shore, where it settles on a sand bar. Sprinting out to the boat, Richard and Neil tie the second anchor chain to the stern, fastening the anchor into the sea bottom, as far out as the chain can reach. Then full speed on the boat engine, while the anchor chain is rolled in, using our winch. This is repeated several times, and slowly, very slowly, the boat is pulled out towards open water. We are much relieved, when the keel is once again under water. Luckily, only minor damage has been done to the boat. The bolts around the rudder having been pulled out, causing water to seep in. Throughout the night, we take turns baling out the boat.

During our stay, we interview the local school teacher.

“How many people live on Kwale Island?”

“About a thousand.”

“How do people here make a living?”

“Most men are fishermen, and the women grow crops like cassava and papaya, and they keep goats.”

“How is life here?”

“Kwale Island is a good place to live. There is a strong feeling of solidarity, and theft is not tolerated. If someone is stealing, he or she must leave the island.”

A thousand people on this small island are far more than it can support. Almost every tree has been cut down for fuel – only a few great baobabs (Adansonia digitata) have been spared. The remaining vegetation is heavily overgrazed by the goats.

Shungu Mbili seems to be an important egg-laying beach for sea turtles. We find carapaces of three or four animals, and no less than eleven nests have been robbed. The local fishermen claim that they don’t kill turtles, or dig up their eggs, but we suspect that they are not telling the truth, as they are probably aware that sea turtles and their eggs are fully protected, according to Tanzanian law.

In the dense vegetation on Shungu Mbili, we find a small nesting colony of the dimorphic egret (Egretta dimorpha), which occurs in two colour morphs, black and white – hence its name.

We spend four days at the large Mafia Island, which turns out to be an important wintering place for waders. In this area, we observe our first lesser frigatebirds (Fregata ariel), and a whale shark (Rhincodon typus) passes under Gaia. It is so huge that we can observe it on both sides of the boat simultaneously!

In this area, we often observe the beautiful African fish eagle (Haliaeetus vocifer), which is fairly common along the Tanzanian coast, and every day, small packs of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa plumbea) are playing in the river near the boat.

Much to our surprise, large areas of riverine forest have been cleared and converted into rice fields. Richard, Neil, Siobhan, and I pay a visit to a village on Kiomboni, one of the larger islands in the delta. To get there, we must wade through plenty of mud. People in the village are very friendly.

Among other crops, they grow coconut palms (Cocos nucifera), but many of these have died, their leaves eaten by coconut rhinoceros beetles (Oryctes rhinoceros). We observe a few brown-headed parrots (Poicephalus cryptoxanthus), sitting in a mango tree. Richard is of the opinion that maybe they are not so good at spelling, since, according to our bird book, this species lives in mangrove.

Leaving the Rufiji River, heading for Boydu Island, we encounter a pair of mating green turtles (Chelonia mydas).

The following morning, I wake up early, noticing that the dinghy is missing. During the night, the rope has been cut by thieves. Sailing downwind, we soon find the dinghy floating – but both outboard engines have been stolen. However, we are very lucky, because one of the locals in the town of Kilindoni is willing to lend us his outboard. Now we can continue our work.

The oldest building here is the Friday Mosque, probably built in the 1100s – one of the largest of its kind in East Africa. Husuni Kubwa is the largest non-European building in all of central and eastern Africa, situated on a hill, from where you have a gorgeous view towards the Indian Ocean. It was probably built c. 1245, during the reign of Sultan al-Malik al-Mansur al-Hasan bin Sulaiman. In southern Arabia, the word husuni refers to a fort-like building. However, Husuni Kubwa is not a fort, but a palace.

On a rocky promontory near the town lie the ruins of Gereza, a huge fort, built c. 1800 by the Sultan of Muscat.

For six days, we are withheld here, unable to go anywhere, as the passports of the four ‘culprits’ have been confiscated. Not only is the officer very unfriendly. It also seems that he is unable to make a decision. Alternately, he orders us to sail back to Dar to get the necessary papers, accompanied by him and an armed guard; to fly to Dar, which we are willing to – but he then changes his mind and forbids us to fly back; and to sail to Lindi to present ourselves to his boss there. Finally, he decides that Ole, Richard, Neil, and Siobhan must go to Lindi by Landrover to meet his boss.

Early the following morning, Thomas and I walk to the small airstrip outside town, Thomas with a flight ticket in his pocket. The friendly staff of Air Tanzania knows all about the affair (in fact, the entire town does), and everybody finds the behaviour of the immigration officer appalling (including his own assistant). We are very nervous that the officer is going to stop us, as he has forbidden us to fly. However, Thomas boards the plane, and I am indeed relieved when I see it disappear in the distance.

The same afternoon, Thomas makes a phone call from Dar, informing us that the four visas have already been changed from transit visas to visitor’s visas. He makes his call at the last moment, as our four friends are already seated in the Landrover, bound for Lindi. The only reason they haven’t left is that the driver wants to make more money by taking extra passengers. Now he won’t make any money at all, as the trip has been cancelled.

The following evening, Thomas arrives in a Landrover, bringing the required documents. Everybody is very happy to see him (except maybe the immigration officer).

However, as we have wasted six days here, our research permit is running out, and it is time to go back to Dar. On our way, we again make a brief stop at Latham Island to ring young masked boobies.