Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Zaire 1981: The ghost forest

We gaze at him, questioningly. The last river? In this dripping wet forest? It sounds really unbelievable. After all, the hike of the day has just begun! However, his statement is true, and we shall soon realize why.

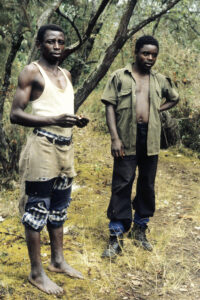

We are two Danes and five Germans, hiking up the Ruwenzori Mountains, situated in the borderland between Zaire* and Uganda. Steffen and I have been travelling with the Germans Wolfgang, Jürgen, Franz, Gisela, and Albert, ever since we met them in Bangui, capital of the Central African Republic (read more on the page Travel episodes – Africa 1980-81: An arduous journey across Africa).

The last participant in the party, Johnny, doesn’t want to participate in the hike due to an inflamed foot.

When Greek scientist Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100-170 A.D.) made his world map, he placed a huge mountain in the heart of Africa, adding this text: “The Mountain of the Moon, feeding the lakes of the Nile with its snow.” Even viewed with today’s eyes, the location and description were astonishingly accurate.

As no European had ever seen these mountains, they turned legendary over time – especially because the thought of snow on the Equator was regarded with scepticism.

Even the great Victorian explorations didn’t cast any light on the issue, and the existence of the mountains was still shrouded in mystery. In 1864, Samuel White Baker (1821-1893) reached Lake Albert, travelling along the Nile, and in 1876, Henry Morton Stanley (1841-1904) managed to reach Lake Edward. Neither of them realized that a mountain range, 120 km long, 65 km wide, and more than 5,000 m high, is situated between these two lakes. The simple explanation is that they are virtually always hidden in fog.

The first European to see these mountains was Stanley, when camping at Lake Albert in 1888. One of his native staff drew his attention to a peculiar phenomenon in the horizon – ‘a mountain of salt’, as he expressed himself. Presumably, the mountains were extremely hazy and might resemble salt from a distance.

The highest peak of the Ruwenzori is Margherita (5109 m), third-highest peak in Africa. The upper regions of the range are permanently snow-covered, with several glaciers. The major part of the mountains are included in two national parks, the Virunga NP in eastern Zaire, which covers an area of 8,090 km2 (including lowlands along Lake Edward), and the Rwenzori Mountains NP in south-western Uganda, covering 998 km2.

There are five overlapping vegetation zones in the Ruwenzori: the rainforest zone (below c. 2,800 m), the bamboo zone (c. 2,800-3,300 m), the heather zone (c. 3,000-3,800 m), the alpine zone (c. 3,500-4,500 m), and the nival zone (c. 4,400-5,000 m). The zones overlap due to local soil composition, and deviating climatic conditions, for instance beneath rock walls.

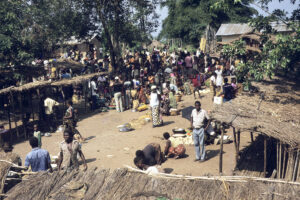

In Beni, we approach the Catholic mission to ask permission to camp on their land. However, this is rejected by the missionaries who claim that the kids will throw stones at us. Instead, we go to the Seventh Day Adventists who readily gives us permission. We are soon surrounded by a crowd of about a hundred friendly and curious villagers who wouldn’t dream of throwing stones at us.

A long-crested eagle (Lophaetus occipitalis), perched in the top of a tree, is watching our doings, its rather grotesque crest waving here and there, when it turns its head.

The following morning, we drive a few kilometers to another village – the starting point of the hike. Initially, the trail leads through farmland with manioc fields and banana plantations. We are quite sweaty when we a couple of hours later make a stop at a house, which is the home of a local man who has been hired by our guide to carry his gear – unlike us who struggle along with heavy backpacks.

A very steep trails leads up to the entrance to the Virunga NP. We are now surrounded by lush rainforest with many tree ferns (Cyathea deckenii) and innumerable other plants, including several species of balsam (Impatiens) and a member of the mallow family (Malvaceae) with yellow flowers. A chorus of cicadas are making a racket in the forest, and we also hear calls of various birds. Of the birds themselves we only get an occasional glimpse, and the only one that we are able to identify is the black saw-wing swallow (Psalidoprocne pristoptera), feeding over the trail.

We are lucky to spot a troup of about 20 beautiful black-and-white colobus monkeys (Colobus guereza) – black with a white beard, a long, white, flowing mane on the back, and a white tip to the tail.

The major part of the day the sky is overcast, but occasionally we get a glimpse of valleys and mountain slopes, whereas the peaks are hidden all day. Exhausted, we reach the first hut, Kalonga, elevation 2,138 m. Here we relax for the rest of the day. Towards evening, the clouds disperse.

Initially, the hike of the day leads down to a small river with fast-running, clear water. Our guides urges us to fill up our water bottles. Then it goes up, up, up, almost throughout the day.

Gradually, the vegetation now changes, showing rather large stands of African alpine bamboo (Yushania alpina). This bamboo species, which may grow almost 20 m tall, was formerly known as Arundinaria alpina. However, together with a large number of other bamboo species, it has been transferred to the genus Yushania, erected in 1957 by Chinese botanist Keng Yi-Li (1898-1975). This rather strange genus name relates to Yu Shan (3952 m), the tallest mountain in Taiwan. Presumably, the type species Y. niitakayamensis was collected on this mountain.

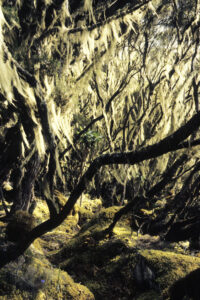

In the Ruwenzoris, African alpine bamboo rarely dominates completely, but is mixed with various broad-leaved trees. As we gain in altitude, heather trees appear, especially Erica kingaensis, but also other members of the genus, including the widespread E. arborea. The trees are draped with old man’s beard lichens (Usnea), which thrive in the humid air, whereas the forest floor is covered by thick moss cushions.

In the acid conditions on the forest floor, turned-over tree trunks take a long time to rot, and decades of decaying trunks lie helter-skelter, overgrown by mosses. The trail has been trodden down into the moss, and we must often climb over over under the trunks.

“Mind where you put your feet,” says the guide, “you can easily twist an ankle on the slippery trunks. Once a scientist broke his leg in this forest. His leg had to be supported by bamboo sticks, and then he was carried all the way down.”

This awful story makes us even more cautious.

The air here is very humid indeed, but the thick moss cushions absorb all the rain water, and this explains the lack of rivers in the forest. This is the reason that our guide instructed us to fill up our water bottles this morning.

Occasionally, we observe a bush with rhododendron-like leaves and bluish-violet berries: Myrsine melanophloeos, previously known as Rapanea rhododendroides.

Flowers are encountered here and there in the heather forest. Disa stairsii, a ground-living orchid with small pink flowers, is fairly common, and various yellow-flowered groundsels of the genus Senecio are also observed. Scadoxus cyrtanthiflorus is a gorgeous member of the amaryllis family (Amaryllidaceae) with orange-red, funnel-shaped flowers, clustered on a short stalk.

Animal life is scarce in the forest. Now and then we hear birds, but the few glimpses we get of them don’t allow us to identify them. The only mammal we observe is a single duiker antelope (Cephalophus).

Our guide makes a halt at a number of small shelters, with small heaps of manioc flower beneath. He explains that here it is the custom to make a small offering to the gods before continuing the hike. Our contribution consists of a little oatmeal and some bits of bread.

Late in the afternoon we finally reach the next hut, Mahangu, situated in the heather forest at an altitude of 3,310 m. The only source of water here is a small puddle in a hole, which has been dug behind the hut to collect rain water. The water is very muddy, and we use Albert’s hat as a filter before boiling the water for 20 min.

The evening is very chilly, and we retire early. Franz, Gisela, and I are snug in our sleeping bags, but the others don’t have sleeping bags and must face a cold night.

At a distance, some look like distorted, petrified ogres, a thick, up to 10 m tall trunk with 2-4 branches, at the end of each branch a rosette of enormous leaves above the withering remains of yesteryear’s leaves. This is a species of giant groundsel, Dendrosenecio adnivalis, a gigantic relative of groundsels of the genus Senecio. These crooked beings may grow for 30-50 years without blooming, then suddenly exploding in an abundance of yellow flowers, gathered in a huge, terminal inflorescence. The strangest thing is that flowering is often synchronized, many individuals blooming simultaneously. After flowering, the plant grows a new branch, and the next flowering takes place at the end of this branch. Research indicates that a plant can only flower four times before dying.

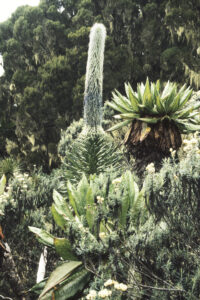

Another gigantic plant here has a large rosette of narrow, pointed leaves, and from the centre of the rosette a long, candle-shaped stem emerges, up to 7 m tall and densely covered in white, felt-like hairs, among which hundreds of small blue flowers are hidden. This plant is Lobelia wollastonii, a gigantic relative of the water lobelia (L. dortmanna) of the Northern Hemisphere. L. wollastonii is frequently paid a visit by the scarlet-tufted sunbird (Nectarinia johnstoni), sucking nectar from the flowers and hereby pollinating them.

Filled with wonder, we walk about in this peculiar forest. The great plants grow at quite some distance from one another, and the space between them is occupied by dense shrubs of a species of everlasting, Helichrysum stuhlmannii, with yellowish flowerheads. The fog occasionally lifts a bit, and we are rewarded with views over a large valley with a couple of lakes, surrounded by enormous, greyish-black mountains with several glaciers.

In this captivating area lies the third hut, Kiondo, at an elevation of about 4,200 m. We scale a small peak near the hut, but the cloud layer is dense, and we never see the mountains in their full majesty.

In the evening, several piercing calls are heard from the forest. Our guide informs us that they are emitted by the tree hyrax (Dendrohyrax arboreus), a relative of the widespread rock hyrax (Procavia capensis). At lower elevations, the tree hyrax lives up to its name, as it is mainly seen in trees. Up here, however, it has taken over the habitat of the rock hyrax, as the latter is not found here.

Exhausted, we reach the brook before the hut, where we get a refreshing bath. The following morning, all our joints are very tender, and the relatively short walk towards Mutsora is undertaken at a leisurely pace. Now we have time to enjoy the wildlife, and among mammals we again observe blue monkey, besides olive baboon (Papio anubis) and red-legged sun squirrel (Heliosciurus rufobrachium).

Bird life is rich, and I note for instance mountain buzzard (Buteo oreophilus), Ruwenzori batis (Batis diops), cinnamon-chested bee-eater (Merops oreobates), grey-throated barbet (Gymnobucco bonapartei), and yellow-bellied greenbul (Chlorocichla flaviventris).

Our last stop is at the porter’s house, where we are served a delicious course, consisting of cooking bananas, beans, and boiled manioc, added a liberal amount of chili.