Wood carvings

Old man, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

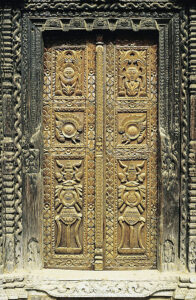

Beautifully carved wooden door in the city of Bhaktapur, Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A crocodile-like monster, Fanø, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Maori wood carving, depicting a super-natural being, was encountered along the road between Raetihi and Ore-Ore, North Island, New Zealand. In his left eye socket is a round piece of mother-of-pearl. Presumably, the right eye socket was once adorned in a similar way, but the mother-of-pearl is now missing. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Carving in wood has appealed to Man since Early Stone Age. What is currently regarded as the world’s oldest wood carving is the so-called Shigir Idol, a totemic sculpture 2.8 m tall. This image, carved in larch wood, was discovered in a peat bog in the Ural Mountains in 1890. Recent test have revealed that it was made about 11,000 years ago.

During my travels, I have often encountered wood carvings of various types. A selection is shown below, arranged country-wise.

Canada

This totem pole at Qualicum Beach, Vancouver Island, depicting a bear, was carved in 1966 by Salish people. The bear was a totem animal for several North American native tribes. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chile

Giant wooden sculpture, depicting an albatross, Valparaiso. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Denmark

In a plantation on the island of Fanø, various images have been carved from dead trees. The following pictures show examples of this artwork.

A gentle wood fairy. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

An exercising ogress. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A rabbit. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A dog, lying on its back. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

An ogre. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A friendly snail. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The crucified Christ, Søndermark Church, Viborg, Jutland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This man, dressed as a Middle Age artisan, is carving printing blocks in a museum, Bornholms Middelaldercenter, on the island of Bornholm. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The common elm (Ulmus glabra), also called wych elm, Scotch elm, or Scots elm, is distributed in the major part of Europe, eastwards to the Ural Mountains, the Caucasus, and the Alborz Mountains of northern Iran.

In Europe, the populations of this species have been drastically reduced by Dutch elm disease, caused by sac fungi of the genus Ophiostoma (formerly called Ceratocystis). These fungi are natives of Asia, where local elm species are resistant to the disease. However, this is not the case in Europe and North America, where the disease is epidemic. Dutch elm disease is dealt with in detail on the page Nature Reserve Vorsø: Dutch elm disease on Vorsø.

In several European countries, artists have carved images into many of the dead elm trees.

This dead elm on the island of Reersø, Zealand, has been transformed into a sculpture, depicting figures from the Norse mythology, including Thor with his hammer, Mjølner, fighting with the Midgard Serpent during Ragnarok. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This picture shows a nest of European hornet (Vespa crabro), built into a cavity in the same tree, above carvings depicting cats and a female figure. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Carving, depicting an Underjordisk (‘Underground Dweller’), a local type of gnome, which is unique to the island of Bornholm. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

According to Danish folklore, Slattenpatten (‘Flaccid Breasts’) is an ogress, or elven woman, from southern Zealand, who is easily identified by her very long, pendulous breasts, which, so it was said, were hanging down to her hip. A number of legends relate incidents, where King Valdemar Atterdag was hunting Slattenpatten with his dogs. In such situations, she would sling her breasts over her shoulders, to avoid them being in the way when she had to run fast.

Slattenpatten steals from people at night, but if you mark bread and other pastry with a cross, she is unable to take it. If you are followed by her, you may escape by running across the furrows of a ploughed field, if it has been ploughed with a steel plough, because she cannot stand steel. You may also escape by jumping across a stream, as she doesn’t like running water either. (Source: Evald Tang Kristensen 1893. Danske Sagn, som de har lydt i Folkemunde, Vol. 2)

This carving below the pulpit in Vejlø Church, Zealand, depicts an ogress with a dog’s head and pendulous breasts – possibly Slattenpatten. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In Chinese mythology, the masculine virtues of the dragon and the feminine virtues of the feng-huang (often erroneously called ‘Chinese Phoenix’) complement one another, and they are often depicted together on Daoist temples.

The wood carving below, observed in Højerup Church, Stevns Klint, Zealand, is probably influenced by Chinese mythology, as it depicts two creatures, which resemble a mixture of dragon and feng-huang.

These creatures are described in detail on the page Religion: Daoism in Taiwan.

(Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

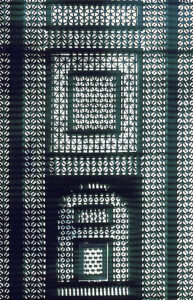

Egypt

Bayt al-Suhaymi (‘House of Suhaymi’) was originally constructed in 1648, during the Ottoman Era, along the Darb al-Asfar in Cairo, which in those days was a very prestigious area of the city. The various buildings of the mansion were erected around a central garden. Today, this house is a museum.

These pictures show some of the Mashrabiya windows in Bayt al–Suhaymi, adorned with wonderfully carved wood latticework. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

France

This ‘dice’ fish was observed in a window in the city of Dinan, Brittany. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These faces, which make fun of you, are carved at the tip of house beams, Malestroit, Brittany. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This face with a worried expression is carved into a house beam in the city of Rochefort en Terre, Brittany. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

India

According to the famous Hindu epic Mahabharata, one of the Pandava brothers, Bhima, spent some time in exile in Manali, Himachal Pradesh. He fell in love with a local beauty, Hadimba (also called Hidimbi), who, as a young woman, had vowed to marry the man, who was able to defeat her brother Hadimb (or Hidimb) – a very brave and strong person. Bhima managed to kill Hadimb, whereupon Hadimba married him. Later, the local people regarded her as a goddess, an incarnation of the supreme Mother Goddess, Devi.

This picture shows a collection of carvings, adorning the Hadimba Temple in Manali, erected in 1553 over a cave in a huge rock, where Hadimba supposedly meditated. Later, this rock was worshipped as an image of the deity. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In the village of Agora, Asi Ganga Valley, Uttarakhand, several of the houses are adorned with beautifully carved columns and beams, made from West Himalayan yew (Taxus contorta) – a tree that has become rather scarce due to over-exploitation. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In the village of Sangam Chatti, Uttarakhand, local women have created art from dead branches, which were washed up along the river banks. Faces are applied to some, whereas others resemble birds or dinosaurs. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Indonesia

Wooden sculpture, depicting a flute player, Bali. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Italy

Bench with face and hands, Ragusa, Sicily. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This sculpture, carved in a trunk of Etna silver birch (Betula pendula ‘aetnensis’), was observed in a forest beneath Etna, Sicily. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Malawi

This road vendor is selling locally produced wood carvings as souvenirs, Chembe, Lake Malawi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

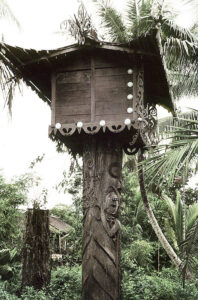

Malaysia

Formerly, when a Dayak tribal chief in Borneo passed away, an ornate burial pole would be erected on his grave. When the pictures below were taken in 1975, this custom had already vanished. You may read about my adventures with a Dayak tribe, the Punan, on the page Travel episodes – Borneo 1975: Canoe trip with Punan tribals.

Dayak tribal chief burial poles in the village of Belaga, Sarawak. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Dayak tribal in Belaga is sitting on an old-fashioned chair, carved out of a tree trunk. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

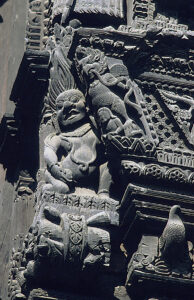

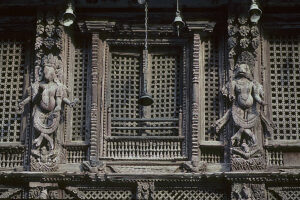

Nepal

Still today, a few houses in Nepalese villages are adorned with beautifully carved window frames, but this millennia-old craft is quickly vanishing, giving way to pre-fabricated windows.

House in the village of Dana, Kali Gandaki Valley, Annapurna. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Two window frames in the village of Thulo Shyabru, which is beautifully situated on a ridge in Langtang National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

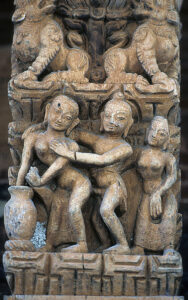

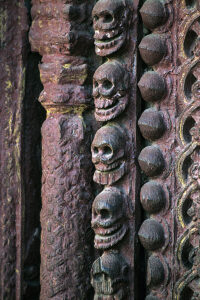

Hindu temples in the Kathmandu Valley are adorned with an abundance of wood carvings, depicting mainly religious issues. Some, however, are more profane!

These carvings on the Old Royal Palace, Durbar Square, Kathmandu, depict a wrestler (malla), and a griffin, devouring a snake. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These carvings, also on the Old Royal Palace, Kathmandu, depict various mythological creatures. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This carving on a temple rafter at Pashupatinath depicts a couple, making love in a rather advanced position. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The carvings on this beam in a Hindu temple, Bhaktapur, depict a deity, possibly Krishna, whose skin was blue, and a woman, giving birth. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These carvings adorn a Hindu temple on Durbar Square, Kathmandu, dedicated to the supreme Mother God, Devi, who, in the form Kali, wears a garland of human skulls. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The picture below, likewise from the Durbar Square, Kathmandu, shows a Vishnu temple with two of this supreme god’s avatars (incarnations). The one to the left is the second avatar, Kurma, half man, half turtle, who plays a vital role in the epic drama The Churning of the Milk Ocean, which you may read about on the page Religion: Hinduism. The figure to the right is the third avatar, Varaha, a gigantic boar, who kills the terrible demon Hiranyaksha.

(Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

New Zealand

For millennia, owls have appealed to people’s imagination due to their nocturnal living, silent flight, and mysterious hooting. They often play a role in indigenous mythologies, and carvings depicting owls are seen in many cultures around the world.

For many years, the Tasmanian spotted owl (Ninox novaeseelandiae), also called morepork or ruru, was regarded as the same species as the Australian boobook (Ninox boobook). However, in 1999, it was decided that Tasmanian and New Zealand populations differed significantly from the mainland populations to form a separate species. Ongoing genetic research of this genus may result in the separation of the Tasmanian and New Zealand populations into two separate species.

The Tasmanian spotted owl was mentioned by English physician and naturalist John Latham (1740-1837) in his work A General Synopsis of Birds (1781-1801), but he did not include a binomial name. It was formally described in 1788 by German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin (1748-1804).

The names morepork and ruru are onomatopoeic, emulating the distinctive two-pitched call of this owl.

These Maori wood carvings on a totem pole in the Wai-O-Tapu Thermal Area, North Island, depict Tasmanian spotted owls, and a fish. Pieces of mother-of-pearl have been placed in the eye sockets of two of the owls. The third one probably also had mother-of-pearl in the eye sockets, but it has disappeared. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fantails, or fantail flycatchers (Rhipidura), are a group of c. 50 species of small insectivorous passerines, which, as their name implies, often spread their tail feathers to form a fan. Formerly, these birds were included in the Old World flycatcher family (Muscicapidae), but today they form a separate family, Rhipiduridae, together with two species of silktail (Lamprolia) and the drongo fantail (Chaetorhynchus papuensis).

Fantails are widely distributed, from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to southern China, the Philippines, and western Polynesia, and southwards through Southeast Asia and Indonesia to Australia and New Zealand.

As its name implies, the New Zealand fantail (Rhipidura fuliginosa) is restricted to New Zealand, where it is common in many places. This species is very confiding and will often flit about in front of your face, catching insects. It is very variable, being mainly grey, white, and pale brown, and it also occurs in a dark morph, which is sometimes called black fantail.

In the Maori language, the New Zealand fantail is known as piwakawaka. It is a messenger, bringing death or news of death from the gods to the people. Its bulbous eyes and erratic flying behaviour is attributed to it being squeezed by the hero Maui, because it would not reveal the whereabouts of his ancestress Mahuika, the fire deity.

Maori wood carving on a totem pole, depicting New Zealand fantail, Wai-O-Tapu Thermal Area, North Island. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Norway

The Oseberg Ship is a very well-preserved Viking ship, unearthed in 1904 from a large burial mound near the Oseberg farm in Vestfold. It is thought to date from about 800 A.D. Today, it is displayed in the Vikingskipshuset (Museum of Viking Ships) in Oslo.

Carvings on the Oseberg Ship, depicting human faces. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The pictures below show other carvings on the Oseberg Ship, depicting the Midgard Serpent, or Jormungand, a giant, which had assumed the form of an enormous monster. The gods tried to drown it by throwing it into the cosmic sea, but it merely wound itself around the entire Midgard (abode of humans), biting its own tail. A völva (a prophetess) had foretold that at Ragnarok, when the world comes to an end, Thor will fight a final battle with the Midgard Serpent, which he succeeds in killing, but he himself will succumb to the monster’s poison.

(Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lom Stavkirke is a stave church in the Gudbrand Valley – one of the largest of its kind in the country. It was probably constructed during the 1100s.

Carved dragon’s head on the roof of the church. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mythical creatures, carved along one of the entrances to the church. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Philippines

In 1984, I spent a few days with wood carver Joseph Blas, who lived in the Ifugao village of Bocos, near Banawe, northern Luzon. My interesting adventures with him are related on the page Travel episodes – Philippines 1984: Shamanism among Ifugao tribals.

One of Joseph’s wood carvings – a door panel in his house, depicting everyday life in an Ifugao village. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These carved wooden figures, depicting house gods, called Bulol, were guarding Joseph’s rice harvest. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sri Lanka

Small wooden mask, depicting a devil. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sweden

The Vasa is a Swedish warship, which was completed in Stockholm in 1628. On its maiden voyage, in August the same year, it sank after sailing only 1,300 m. Most of her bronze cannon were salvaged shortly after, but then the ship was largely forgotten, until it was found again in the late 1950s. In 1961, it was salvaged, with a largely intact hull, and in 1988 it was moved to the Vasa Museum in Stockholm.

Wood carvings, adorning the hull of the Vasa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Taiwan

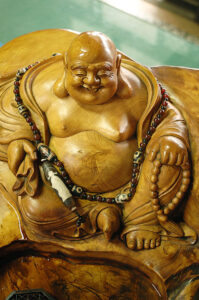

Wood carving is a millennia-old tradition in Taiwan.

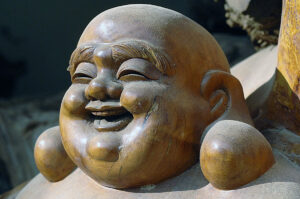

Budai, often called ‘The Laughing Buddha’, does not represent the Buddha Sakyamuni, as is sometimes believed by Westerners. He is a bodhisattva, a Buddhist, who is on the threshold of nirvana, but who, instead of entering this ultimate state, chooses to use his knowledge to help other persons towards the same goal.

Budai is usually regarded as an incarnation of Maitreya, the ‘Future Buddha’, who, it is said, will return to Earth in due time to save humanity. The word budai means ‘a sack made of cloth’. This name has been applied to him, as he is usually seen carrying a sack over his shoulder. When asked why he is carrying this sack, he will just throw it to the ground, smiling, indicating that you should let go of all desires – the final goal of all Buddhists.

Two images, depicting Budai, Sanyi. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

According to tradition, the Indian Buddhist missionary Damo (also called Bodhidharma), was the person who brought Buddhism to China, c. 450-500 A.D. It is said that three years after his death, Chinese ambassador Song Yun met him walking in the mountains, carrying one sandal, tied to a stick on his shoulder. Song Yun asked him where he was going, to which he replied, “I am going home.” When asked, why he was carrying only one sandal, he answered, “You will know when you reach the Shaolin Monastery. Don’t mention that you saw me, or you will meet with disaster.”

Regardless of Damo’s warning, Song Yun told the emperor that he had met him, to which the emperor replied that he was already dead and buried, whereupon he let Song Yun arrest for lying. When they arrived at the Shaolin Monastery, the monks informed them that Damo had been buried in a hill behind the temple. When the grave was opened, the coffin only contained a single sandal. The monks exclaimed, “Master has gone back home,” whereupon they prostrated three times.

This wood carver in the town of Sanyi is working on a sculpture, depicting the Indian Buddhist missionary Damo. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wood carvings, depicting Damo, Sanyi. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wood carvings, depicting Damo, Dongshih, central Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Carving from Sanyi, depicting a Chinese nobleman. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Two monkeys, seemingly ready for pranks, Sanyi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

For millennia, owls have appealed to people’s imagination due to their nocturnal living, silent flight, and mysterious hooting. They often play a role in indigenous mythologies, and carvings depicting owls are seen in many cultures around the world.

The owl appears in the mythology of several Taiwanese indigenous peoples. This carving was exhibited at Buluowan, Taroko Gorge. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Daoist wooden images in the Fushing Temple, Xiluo, depicting Lohan (‘Worthy Ones’), i.e. persons, who have attained a very high level of knowledge and understanding. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Guan Yu, also known as Guan Gong (160-220 A.D.), was originally a military general, serving under the warlord Liu Bei during the late Eastern Han Dynasty (c. 25-184 A.D.). Among Daoists, he is regarded as a subduer of demons, revered as a deity for his righteousness, loyalty, and forgiveness.

Carvings, depicting mythical lions and an elephant-like creature, Guan Gong Daoist Temple, Tainan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In Chinese mythology, the masculine virtues of the dragon and the feminine virtues of the feng-huang (often erroneously called ‘Chinese Phoenix’) complement one another, and they are often depicted together on Daoist temples.

Carvings, depicting dragons, Gong Fan Daoist Temple, Mailiao. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Carving, depicting a feng-huang, Gong Fan Temple. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Carving, depicting a mythical lion, Gong Fan Temple. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Carvings in a Daoist temple, Shinggang. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In Daoism, the tiger god, Hu Ye, is often depicted with rabbit front teeth, as well as with exposed canine teeth. A number of picture, depicting images of the tiger god, are shown on the page Religion: Daoism in Taiwan.

This wood carving, depicting the tiger god, was observed in Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This small section of a sawn tree trunk has been placed vertically, adorned with a carved duck and a flower pot, Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

For several years now, a collection of weather-beaten sculptures has been exhibited outside a wood carver’s workshop in the city of Taichung.

(Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These images have lost part of the colours. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This carving, depicting a Daoist goddess, has been invaded by termites. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These wood carvings probably depict Daoist scholars. Note the image of the woman, which has been placed, so that it looks like she is peeping out from behind a window. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This carving depicts a sika deer (Cervus nippon), which was almost exterminated in Taiwan due to excessive hunting. It has now been re-introduced in several places. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pictures, depicting wood carvings produced by Taiwanese tribal minorities, are shown on the page Culture: Tribal art of Taiwan.

Thailand

In the town of Damnoensaduak, this artist is carving figures into a tabletop, including elephants and trees. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Turkey

This carving in the town of Amasra, Black Sea Coast, depicts a cart, pulled by an emaciated donkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

United States

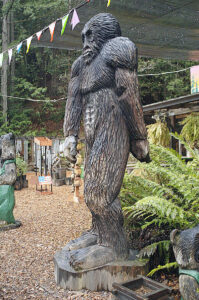

Driving through California, I came across two storage places for hundreds of kitschy wood carvings, at Garberville and Leggett. Several of these are shown below.

Native Americans. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pinocchio and the fairy. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A friendly bear. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The famous ’Bigfoot’, a creature like the Himalayan Yeti – a giant, human-like ape, which supposedly roams the forests of western United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Carving, depicting a fight between a bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) and a mountain lion (Puma concolor). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

For millennia, owls have appealed to people’s imagination due to their nocturnal living, silent flight, and mysterious hooting. They often play a role in indigenous mythologies, and carvings depicting owls are seen in many cultures around the world.

The American great horned owl (Bubo virginianus) is a large owl with an enormous distribution, found from Alaska and northern Canada southwards through the entire United States to southern Mexico and Guatemala, and also in two separate areas of South America, from Columbia eastwards to north-eastern Brazil, and south of the Amazon Basin, from eastern Peru eastwards to the Atlantic Ocean, and thence southwards to north-eastern Argentina.

Another American bird, the great blue heron (Ardea herodias), is also widely distributed, from Alaska southwards to the extreme north-western South America.

Wooden window panels in the Wendell Gilley Museum, Mount Island, Acadia National Park, Maine, depicting a great horned owl and a great blue heron. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Carving, depicting ‘Charlie’, mascot of the town of Charlton, Coos Bay, Oregon. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Vietnam

These fearsome fish, carved in drift wood, were observed in the city of Da Nang. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Uploaded March 2018)

(Latest update February 2025)