Urban plant life

Railroad creeper (Ipomoea cairica, Convolvulaceae), creeping along barbwire, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

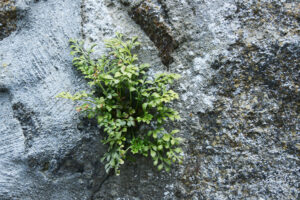

This spreading pellitory-of-the-wall (Parietaria judaica, Urticaceae) has sprouted in a hole on a house wall, Sultanahmet, Istanbul, Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mexican primrose-willowherb (Ludwigia octovalvis, Onagraceae), growing along the Han River, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Asiatic dayflower (Commelina communis, Commelinaceae) has sprouted in a crack along a house wall, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Withered peacock-plume grass (Chloris barbata, Poaceae) is often very decorative. These specimens are illuminated by the morning sun against a dark wall in the city of Taichung, Taiwan. The small plants are lantern tridax (Tridax procumbens, Asteraceae). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Traditionally, fungi and lichens were regarded as plants, and although they now belong to separate kingdoms, I include them here, as most people still regard them as plants. A few species are presented at the bottom of the page.

Acanthaceae Acanthus family

A huge family, counting about 229 genera with c. 4,000 species of herbs, shrubs, climbers, or trees, distributed in most parts of the world.

A popular name of this family is bear’s breeches family. This strange name builds on a misunderstanding. A medieval Latin name of the plant, which Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), later named Acanthus mollis, was Acanthus sativus branca ursina (‘cultivated spiny (plant with) bear bracts’), alluding to the curved bracts of the inflorescence, which, to those who named the plant, apparently resembled a bear’s claws. Over time, branca was corrupted to breech, leading to the name bear’s breeches.

Ruellia

This huge genus, containing about 365 species, native to tropical and subtropical areas in the Americas, Africa, southern Asia, and Australia. They are sometimes called wild petunias due to their resemblance to true petunias (Petunia), of the nightshade family (Solanaceae).

The generic name honours French herbalist and physician Jean Ruelle (1474-1537), who translated works of Greek physician, pharmacologist, and botanist Pedanius Dioscorides (died 90 A.D.), who was the author of De Materia Medica, 5 volumes dealing with herbal medicine.

Ruellia tuberosa

This species is native to Central America, but is widely cultivated elsewhere and has become naturalized in several places, including eastern Africa, the Indian Subcontinent, and Southeast Asia.

Naturalized Ruellia tuberosa, growing in a crack in a wall along a drainage canal, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Amaranthaceae Amaranth family

This worldwide family contains about 174 genera with 2,100 to 2,500 species of herbs or shrubs, rarely trees or climbers. Many of the species were formerly in the goosefoot family (Chenopodiaceae), which is now regarded as a subfamily, Chenopodioideae, of the amaranth family.

Alternanthera

Members of this genus are characterized by their whitish, papery flowers. The number of species varies enormously, from 80 to 200, depending on authority. These plants, also known as joyweed or Joseph’s coat, mainly stem from South America, with some species native to Asia, Africa, and Australia. Many species have been accidentally introduced elsewhere, and several are regarded as noxious weeds.

The generic name is derived from the Latin alternus (‘alternate’), and Ancient Greek anthera (‘anther’), presumably referring to the anthers being alternately fertile and barren.

Alternanthera sessilis Sessile joyweed

This creeping plant is native to South America, but has been spread to more than 30 countries in warmer regions around the world. It is a pioneer plant, growing in a wide range of habitats, including marshes, margins of streams, damp forests, and open disturbed areas, such as lawns and abandoned plots. It is also a weed in fields.

In many places, it has become a huge problem in water courses, as it may block the flow of water. It is listed as invasive in a number of countries, including Spain, United States, New Zealand, India, China, Taiwan, Namibia, and South Africa.

The specific name refers to the unstalked inflorescences.

Sessile joyweed is very common in Taiwan, also in cities. These have sprouted in a crack in a pavement (top), and in an abandoned plot, Taichung. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Amaranthus Pigweed, amaranth

A worldwide genus with about 75 species.

In his delightful book All about Weeds, Dover Publications (1974), American botanist Edwin Spencer (1881-1964) says about a species of pigweed, A. retroflexus:“One of the most robust, devil-may-care weeds is the pigweed. ‘Careless weed’ is another of its common names, and it comes by this name honestly enough. In good rich soil, it cares for nothing. Wind, hail, fair weather and foul are all the same to the pigweed. Nor does it care what plants are its competitors. It can usually shoulder our any plant within reach, and it has a considerable reach. The name pigweed, however, has no reference to the piggish nature of the plant. It refers to the gustatory pleasure the weed affords pigs. Hogs will leave their corn to feast on pigweeds. In spite of its bristly appearance (it always reminds one of a boisterous young sailor with a week’s growth of sandy beard on his face and his cap on the side of his head), the leaves are tender, and if the smacking of lips and satisfied grunts mean the same thing to pigs that they do to Man, the weeds must be delicious.”

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek a (‘not’, ‘without’) and maraino (‘to wither’), given in reference to the flowers, which last a very long time.

Amaranthus viridis Slender amaranth

The native area of this species, also known as green amaranth, is unknown, and today it is distributed in all warmer areas of the world.

Leaves, as well as seeds, are eaten in many parts of the world. In Australia, this plant was also a source of food during the 19th Century. In 1889, botanist Joseph Maiden (1859-1925) wrote: “It is an excellent substitute for spinach, being far superior to much of the leaves of the white beet sold for spinach in Sydney. Next to spinach it seems to be most like boiled nettle leaves, which when young are used in England, and are excellent. This amarantus should be cooked like spinach, and as it becomes more widely known, it is sure to be popular, except amongst persons who may consider it beneath their dignity to have anything to do with so common a weed.” (Source: T. Low, 1985. Wild Herbs of Australia & New Zealand. Angus & Robertson)

In India, slender amaranth is utilized in traditional Ayurvedic medicine.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘green’.

In Taiwan, slender amaranth is very common in cities, especially in fallow areas, and along roads and embankments. These pictures are all from Taichung. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Celosia Cockscomb

This genus contains about 45 species, native to tropical and subtropical areas of Central and South America, Africa, Arabia, and the Indian Subcontinent.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek keleos (‘burning’ or ‘blazing’), alluding to the colourful inflorescences.

Celosia argentea Silver cockscomb

Like the slender amaranth, the native area of this species, also called feathery amaranth, is unknown, and today it is found in most tropical and subtropical areas of the world. It is regarded as an invasive plant in numerous countries, including India, Japan, Ecuador (Galapagos Islands), Fiji, Taiwan, and the United States.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘silvery’, like the common name alluding to the ripe inflorescences, which shine like silver.

Silver cockscomb is described in depth on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Silver cockscomb is abundant in Taiwan, also in cities, where it often grows in abandoned plots, in this case in Taichung. Downy bur-marigold (Bidens pilosa, see below), likewise an invasive species, is also seen in the picture. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Silver cockscomb, growing in an abandoned parking lot, Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this picture, silver cockscomb completely covers the bottom of a drainage canal in Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anacardiaceae Sumac family

This family, comprising about 83 genera with c. 860 species, is native to tropical and subtropical areas around the world, with a few species occurring in temperate regions. Several species are economically important fruit and nut crops, including the cashew tree (Anacardium occidentale).

The family name is derived from the Greek ana (‘upwards’) and kardia (‘heart’), alluding to the heart of the fruit (the ‘nut’) of the cashew nut, which is outwardly located.

Rhus Sumac

Sumacs are a genus of c. 35 species, distributed in subtropical and temperate areas, especially around the Mediterranean, and in Asia, Australia, and North America. Other species, which were formerly placed in Rhus, have now been transferred to the genus Searsia, others to Toxicodendron, including poison ivy and poison oak, described on the page Autumn.

The word sumac is derived from Ancient Syriac summaq (‘red’), referring to the red fruits of the genus. They have an acrid taste and are used as a spice. In North America, the fruits of staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina) are soaked in cold water to make ‘pink lemonade’, a refreshing beverage, rich in vitamin C.

Rhus coriaria Elm-leaved sumac

This species, also known by other names, including tanner’s sumac and Sicilian sumac, is native from the entire Mediterranean region eastwards through the Caucasus and the Middle East to Kyrgyzstan and Afghanistan. It is also found on the Canary Islands and Madeira.

It is a shrub, growing to 5 m tall, leaves pinnately divided, with 7-8 pairs of ovate leaflets. The inflorescence is a terminal cluster of small white flowers, which later become brownish-red or greenish-yellow drupes, with a very acidic taste. They are dried and crushed to be used as a spice, which, together with other spices, form a mixture called za’atar.

Leaves and bark contain tannic acid and were formerly used in leather tanning, hence the specific name, derived from the Latin coriarium (‘leather’ or ‘tanning’). Various parts of the plant yield red, yellow, black, or brown dyes. Oil from the seeds are utilized to make candles.

Elm-leaved sumac is very common in Turkey. This one has taken root on the wall of an abandoned house in Sultanahmet, Istanbul. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Apiaceae (Umbelliferae) Carrot family

A huge worldwide family, containing about 434 genera with c. 3,700 species of herbs. Many species are economically important crops.

The inflorescence of this family is unique. In almost all species, the flowers are arranged in terminal umbels, which may be simple, usually with bracts at the base, and each of the stalks, the so-called primary rays, ending in a flower. More commonly, the umbel is compound, consisting of a number of primary rays, each ending in a secondary umbel. Each of these umbels usually has small bracts, bracteoles, at the base, and a number of secondary rays, each ending in a flower. Usually, the secondary umbels together form a flat-topped inflorescence, mostly with white, yellow, pink, or purple flowers, rarely blue or bright red. The flowers have five petals and stamens. This also accounts for the sepals, if they are present. They are usually missing, however.

The family name is derived from the name of honey bees, genus Apis, referring to the fact that many plants of the family are much visited by bees and other nectar-sucking insects, in particular hovering flies.

Aegopodium

A genus with 12 species, found in Eurasia.

The generic name is explained below.

Aegopodium podagraria Goutweed

As far back as Ancient Rome, and throughout the Middle Ages, young leaves of goutweed were utilized as a vegetable, much as spinach is used. The generic name is from the Greek aix, genitive aigos (’goat’), and podion, diminutive of pous (’foot’), thus ‘little goat-foot’, referring to the shape of the leaves. According to the Doctrine of Signatures, Our Lord had shaped the plants, so that humans were able to discover what ailments they could be used for. Therefore, goutweed must be an effective remedy for gout. Medicinally, however, there is no basis for this assertion. It was also used as a laxative.

Goutweed is native to southern Europe and western Asia, but was introduced as a garden plant to northern Europe as early as the Middle Ages. It has also been accidentally introduced to North America, and almost everywhere it has become a most annoying garden weed.

In this picture, goutweed is growing out through a beech hedge alongside a pavement. – Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Goutweed as a garden weed, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chaerophyllum Chervil

A genus with about 35 species, native to Europe, North Africa, Asia, and North America.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek khairephyllon, from khairo (‘to be glad’) and phyllon (‘leaf’), the classical name of garden chervil (Anthriscus cerefolium), a culinary herb, which is much used in Mediterrenean kitchens. Botanically speaking, however, the word chervil also applies to members of the genus Chaerophyllum.

Chaerophyllum temulum Rough chervil

This pioneer plant is found in a variety of habitats, including forest edges, waste places, and along walls and fences. It is distributed in the major part of Europe, eastwards to the Ural Mountains, the Caucasus, and Turkey, and also in north-western Africa.

The purplish, very hairy stem grows to about 1 m tall, leaves long-stalked, twice or thrice pinnate, pale or dark green, lobes ovate in outline, deeply toothed. Flowers are white. The plant is poisonous.

The generic name is derived from the Greek chairo (‘to please’) and phyllon (‘leaf’), thus ‘with pleasant foliage’. The specific name is from the Latin temulentum (‘drunken’), derived from temetum (‘an intoxicating drink’) and ulentus (‘full of’), alluding to the symptoms from poisoning by the plant being similar to those of alcoholic intoxication.

Rough chervil, growing at a house wall, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Apocynaceae Dogbane family

This almost worldwide family contains about 415-425 genera with c. 4,500 species of trees, shrubs, or climbers, rarely herbs.

The family name is derived from Ancient Greek apo (‘away’) and kyon (‘dog’), alluding to the toxic dogbane (Cionura erecta), which was formerly utilized to poison dogs.

A large number of genera in this family formerly constituted the milkweed family (Asclepiadaceae), which is today regarded as a subfamily, Asclepiadoideae, of the dogbane family. An amusing description of the peculiar pollination method in the genus Asclepias is found on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Catharanthus Periwinkle

A small genus with 8 species, all but one endemic to Madagascar, with a single species, C. pusillus, native to India and Sri Lanka. Previously, these plants were included in the genus Vinca.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek katharos (‘pure’) and anthos (‘flower’).

Catharanthus roseus Madagascar periwinkle

This pretty plant is native to Madagascar, but is widely cultivated in warmer areas as an ornamental and sometimes escapes cultivation. It is also widely used as a medicinal plant, as it is a source of drugs, used in the treatment of cancer.

Madagascar periwinkle, growing in a crack in a concrete wall along a drainage canal, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Aspleniaceae Spleenwort family

According to Kew Gardens, London, this family of ferns today contains 24 genera, distributed almost worldwide, with the exception of Antarctica and the high Arctic. They grow in soil, on rocks, or as epiphytes, and a few are aquatic.

Asplenium Spleenwort, bird’s-nest ferns

This huge genus, comprising about 700 species, is found in almost all parts of the world. They differ in size from tiny plants to the huge epiphytic bird’s-nest ferns, some of which grow to more than 1 m across, with fronds up to 1.5 m long.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek asplenon, the classical name of spleenworts, ultimately from splen (‘spleen’), alluding to its usage to cure anthrax in livestock.

Asplenium ceterach Rusty-backed fern

This evergreen fern, previously known as Ceterach officinarum, grows in cracks in limestone rocks, and on old walls. It is distributed from the British Isles and Germany southwards to northern Africa, and thence eastwards to Kazakhstan, Xinjiang, and Tibet, found from sea level up to elevations around 2,700 m.

It is a small, compact fern, growing to about 20 cm tall, fronds narrowly elliptic in outline, to 8 cm long and 1.6 cm broad, pinnately divided into 6-8 alternate, triangular pairs. The underside is covered in a dense layer of pale reddish-brown scales, giving rise to the common name. The leaves roll up in hot weather, displaying the scaly underside.

Previously, this fern was much utilized as a medicinal herb for treatment of a large variety of ailments.

The specific name is an ancient name of this plant, derived from the Persian name of it, cedracca.

Rusty-backed fern, growing on a churchyard wall, Hirel, Brittany. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Asplenium ruta-muraria Wall-rue

This small fern grows exclusively on limestone and other calcareous rocks, including walls of old buildings. The fronds are green or bluish-green, much divided, up to 12 cm long. The sporangia clusters are blackish-brown, situated on the underside of the leaflets.

It is a very widespread plant, found in all of Europe, eastwards across most of Siberia, in North Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia, the Himalaya, and China. In Central Asia, it grows up to elevations of c. 3,300 m.

The specific and common names refer to the fact that it often grows on walls, and to the likeness of its leaves to those of common rue (Ruta graveolens).

Wall-rue, growing on an old wall, St. Malo, Brittany. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Asplenium trichomanes Maidenhair spleenwort

A small plant, forming tufts from a short, scaly rhizome. The evergreen fronds are narrow, usually to 20 cm long, sometimes to 30 cm, gradually tapering towards the tip, pinnately divided into small, rounded or slightly elongated, yellowish-green to dark green leaflets. The rachis (stem of the frond) is brownish-black. Sporangia clusters small, 1-3.5 mm long, on the underside of the leaflets.

This plant is very widely distributed, found in scattered locations in most parts of the world, growing in rocky habitats and on walls, from sea-level up to about 3,000 m. It is fairly common in the Pyrenees and the Alps.

This species and its near relatives were much utilized in traditional herbal medicine. Greek physician, pharmacologist, and botanist Pedanius Dioscorides (died 90 A.D.) and Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder (23-79 A.D.) both distinguished between a pale and a black adianton. They were variously called polytrichon (‘many hairs’), kallitrichon (‘fair hair’), trichomanes (‘fine hair’), and capillus veneris (‘venus hair’). They were supposed to possess general anti-toxic properties, used as a diuretic, to expel kidney stones, to cure pulmonary problems, jaundice, spleen diseases, and skin ailments, and to promote hair growth.

The specific name is explained above.

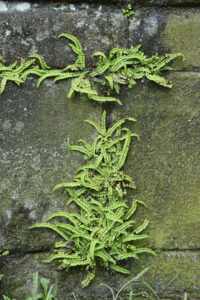

Maidenhair spleenwort, growing on the algae-covered wall of Basilique Saint-Sauveur, Dinan, Brittany. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Blechnum Hard ferns

A large genus with about 240 species, found in most parts of the world, with the exception of the polar regions, Siberia, north-eastern North America, and desert areas.

The generic name is derived from blechnon, an Ancient Greek term for ferns in general.

These plants were formerly placed in a separate family, Blechnacae, which is today regarded as a subfamily of the spleenwort family.

Blechnum orientale Oriental hard fern

This large fern, with fronds sometimes reaching a length of 2 m, is distributed from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to southern China, Taiwan, and southern Japan, and thence southwards through Southeast Asia to New Guinea, Australia, and islands in the western Pacific. Elsewhere, it is cultivated as an ornamental, and plants are sometimes harvested from the wild to be used for food or medicine.

Oriental hard fern, growing on a humid house wall, Hanoi, Vietnam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This oriental hard fern is clinging to a crack in a wall along a drainage canal, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this picture, oriental hard fern is growing on a concrete wall along the Suei Wei River, Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is growing in a crack along a balcony, Hanoi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Asteraceae (Compositae) Daisy family

This worldwide family is one of the largest, comprising about 1,620 genera with c. 24,000 species of herbs or shrubs, rarely climbers or trees.

The inflorescence consists of many individual flowers, called florets, which are grouped densely together to form a flower-like structure, the flowerhead, technically called the capitulum. The flowerhead is surrounded by an involucre, consisting of densely packed green bracts, often erroneously called a calyx. The central disk florets are symmetric, and the corolla is fused into a tube. The outer ray florets are asymmetric, the corolla having one large lobe, which is often erroneously called a petal. In some species, ray florets, or sometimes disk florets, are absent.

Achillea Yarrow, milfoil, sneezewort

A large genus of about 200 species, found mainly in Europe and temperate areas of Asia.

English herbalist John Gerard (c. 1545-1612) informs us that during the Trojan War the Greek hero Achilles used yarrow to stop bleeding on wounded soldiers. Hence, the name Achillea was applied to the genus by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778). It was already mentioned as a medical herb in De simplicium medicamentorum facultatibus, written by Greek-Roman physician, surgeon, and philosopher Aelius Galenus (c. 129-210 A.D.), also known as Claudius Galenus or Galen of Pergamon.

Various plants, including yarrow, were found in a 50-60,000-year-old Neanderthal grave in Iraq, perhaps indicating that these plants were used medicinally. (Source: G.P. Shipley & K. Kindscher 2016. Evidence for the Paleoethnobotany of the Neanderthal: A Review of the Literature. hindawi.com/journals/scientifica/2016/8927654)

The name yarrow is a corruption of gearwe, an ancient Anglo-Saxon name for common yarrow (below).

Achillea millefolium Common yarrow

A widespread plant, to 90 cm tall, found in temperate areas of Eurasia and North America, mainly growing in disturbed areas, along roads and ditches, and in fallow fields. It was introduced as a fodder plant to Australia and New Zealand, where it has become naturalized in several areas. In montane areas of south-eastern Australia, it is regarded as an invasive weed.

The greyish-green leaves are very finely dissected, aromatic, to 10 cm long. Flowerheads are numerous, sometimes up to 50, borne in a flat or slightly domed cluster to 30 cm across. Ray florets are white, much larger than the tiny yellowish or cream-coloured disc florets. The entire flowerhead is only to 8 mm across.

The specific name is derived from the many fine segments of the leaves, hence its popular names milfoil and thousand-weed. In parts of south-western United States, it is called plumajillo (Spanish for ‘little feather’), likewise alluding to the leaves.

The role of this species in folklore and traditional medicine is described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Dwarf form of common yarrow, growing among cobbled stones, together with buck’s-horn plantain (Plantago coronopus), Nyborg, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ageratum Goat-weed, whiteweed, bluemink

A genus with about 40 species, native to the Americas, with most species in Mexico and Central America. Many species have become widely naturalized worldwide in tropical and subtropical areas, often regarded as invasive weeds.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek a (‘without’) and geras (‘old age’), alluding to the fact that these plants flower for a long period of time.

Ageratum conyzoides Goat-weed

This plant, and the rather similar Mexican blueweed (A. houstonianum), are both native to Central and South America, but have become naturalized worldwide in tropical and subtropical areas. Both are regarded as invasive weeds in numerous countries around the world, in Africa, Southeast Asia, China, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.

The medical usage of these plants is described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Large growth of goat-weed along a fence, Hanoi, Vietnam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Artemisia Mugwort

A huge, worldwide genus, counting between 200 and 400 species. Besides mugwort, common names of these plants include wormwood and sagebrush. The genus is presented in depth on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

A picture, depicting lance-leaved mugwort (A. lancea), is shown below at Ixeridium laevigatum.

Artemisia vulgaris Common mugwort

This plant is native to the major part of Temperate Europe and Asia, and also to North Africa and Alaska. In other areas of North America, it has become naturalized. Originally, it was restricted to dry grasslands and sandy beaches, but when farming was introduced, it readily spread to fields, and today it is regarded as a noxious weed.

In China, this species is sometimes used as a substitute for A. argyii to make moxa, which is much utilized as a healer in traditional Chinese medicine.

Common mugwort, growing near a canal in Copenhagen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bidens Bur-marigold

This genus of herbs, comprising between 150 and 250 species, is mainly native to warmer areas of North and South America. However, a large number of species have been accidentally introduced to many other warmer parts of the world.

The generic name is from the Latin bi (’two’) and dens (’tooth’), alluding to the mostly 2 (sometimes 3 or 4) sharp, hooked teeth on the seeds, which easily get attached to animal pelts or people’s clothes, hereby often being spread a considerable distance from the mother plant. This way of seed dispersal has given rise to names like beggar-ticks, stickseed, farmer’s friend (sic!), needle grass, Spanish needles, stick-tight, cobbler’s pegs, Devil’s needles, and Devil’s pitchfork.

Bidens pilosa Downy bur-marigold

This pan-tropical and -subtropical weed, of unknown origin, has become a pest in numerous places, expelling native species. One isolated plant can produce over 30,000 hooked seeds, which are readily spread by sticking to animals’ furs, socks, trousers, etc.

A South African website, farmersweekly.co.za/animals/horses/beware-those-blackjacks, says: “The common blackjack is not only an irritant to horses, (but) can cause them injury. (…) There can be few of us who have not spent ages picking them off our clothes after walking through the veld to catch horses in the early winter. Blackjacks that become entangled in the forelock of a horse can be a great irritant, and the animal will toss its head, if you try to remove them. The spines can injure the eyes, so it’s better to clip the forelocks short. Blackjacks can also get caught up in the long hair behind the fetlocks and pasterns, causing chronic irritation and lameness.”

Downy bur-marigold is reported to be a weed of 31 crops in more than 40 countries, Latin America and eastern Africa having the worst infestations. (Source: cabi.org/isc/datasheet/9148)

However, this species is not only a troublesome weed, but also has medicinal properties. In traditional Chinese medicine, it is used for a large number of ailments, including influenza, colds, fever, sore throat, appendicitis, hepatitis, malaria, and haemorrhoids. Due to its high content of fiber, it is beneficial to the cardiovascular system, and it has been used with success in treatment of diabetes.

In Taiwan, downy bur-marigold is extremely common, often covering huge areas, including in cities, where it pops up everywhere, as is obvious from the pictures below, all from Taichung.

In this picture, downy bur-marigold is growing at the edge of a parking lot. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These have sprouted in a drainage canal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is growing up a fence. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Here, a specimen has taken root between two road dividers. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A form of downy bur-marigold with pinkish petals. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These pictures show the characteristic fruits of downy bur-marigold. The hooked seeds will cling to almost anything. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calyptocarpus

This genus contains about 4 species, distributed in the southern United States and Latin America.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kalypto (‘covered’ or ‘hidden’) and karpos (‘fruit’).

Calyptocarpus vialis

This creeping plant is native from Mexico eastwards to Venezuela, and is also found in southern Louisiana and Texas, and in the Caribbean. It has become naturalized in many other countries, including India, Australia, China, and Taiwan. It grows in lawns and other disturbed places, such as roadsides and trails.

In Taiwan, Calyptocarpus vialis is a common city plant, often growing in cracks along sidewalks. These were photographed in Taichung. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A large growth of Calyptocarpus vialis, climbing up a long-term parked bicycle, Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this picture from Taichung, Calyptocarpus vialis covers the ground around a planted tree. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Crassocephalum Thickhead, rag-leaf

About 48 species, indigenous to Africa and Madagascar. Several members have been accidentally introduced to other parts of the world. Some species are cultivated as vegetables and for medicine, especially in West Africa.

The generic name is derived from the Latin crassus (‘thick’ or ‘stout’), and Ancient Greek kephale (‘head’), presumably alluding to the rather robust flowerheads.

Crassocephalum crepidioides Red-flower rag-leaf

This plant, which may sometimes reach a height of 1.7 m, is native to Africa, but has become naturalized in most warmer areas around the world, growing in open areas, fallow fields, along trails, and in cities.

The numerous flowerheads, to 1 cm across, are in terminal clusters. Ray florets are missing, disc florets have a unique reddish-brown colour, more rarely orange or yellow. Leaves are mostly elliptic, to 12 cm long and 5 cm wide, hairless, margin irregularly toothed, sometimes pinnately lobed at the base.

It is used medicinally for indigestion and diarrhoea, and to invigorate the spleen. In Nepal, juice of the plant is applied to wounds, and young leaves and stems are eaten as a vegetable. Young flowerheads emit a mango-like fragrance when crushed.

The specific name means ‘resembling Crepis‘ (see below).

Other pictures, depicting Crassocephalum, are shown on the page Plants: Himalayan flora 1.

Red-flower rag-leaf, growing next to a house wall, Kathmandu, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Crepis Hawk’s-beard

This large genus, comprising about 200 species, is distributed in the Northern Hemisphere and Africa, with the core area around the Mediterranean.

The generic name is derived from the Greek krepis (‘slipper’ or ‘sandal’), according to some authorities referring to the shape of the fruit.

Crepis capillaris Smooth hawk’s-beard

A widespread plant, native to the major part of Europe, eastwards to the Ural Mountains and the Caucasus, but widely introduced elsewhere, including North America, the northern Andes, South Africa, and Australia. It grows to 60 cm tall, with numerous pale yellow flowerheads to 1.5 cm across.

In these pictures, smooth hawk’s-beard has sprouted in cracks in house walls, Brugge, Belgium (top), and Laven, Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cyanthillium Ironweed

This genus contains 12 species, found in warmer regions of Africa, southern and eastern Asia, and Australia.

Presumably, the generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kyanos (‘blue’) and anthyllion (‘little flower’), alluding to the corolla.

Cyanthillium cinereum Little ironweed

This plant, previously known as Vernonia cinerea, is native to tropical areas of Africa and Arabia, and from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to Japan, and thence southwards to eastern Australia and many islands in the Pacific. It has become naturalized elsewhere, including Latin America, the Caribbean, and southern United States.

It may grow to 1.2 m tall, with a many-branched inflorescence, containing numerous flowerheads with pinkish or purplish florets, all disc florets.

It is used medicinally for colds, and as a means to stop smoking.

It resembles Emilia sonchifolia (below), but that species is smaller, with a much smaller inflorescence, often with only a few flowerheads.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘ash-coloured’ or ‘grey’. It may refer to the stems.

Little ironweed, growing in open areas, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Emilia Tasselflower

This genus contains c. 115 species, distributed mainly in tropical and subtropical areas of Africa and Asia.

The generic name may allude to a person named Emilie or Emily, but when French botanist Alexandre Henri Gabriel de Cassini (1781-1832) named the genus in 1815, he did not give any explanation.

Emilia sonchifolia Lilac tasselflower

Lilac tasselflower may grow to 70 cm tall, but is often much smaller. It is probably native to South and East Asia, but is today widespread in tropical and subtropical regions around the world.

This plant is also known as Cupid’s shaving brush, named for Cupid, the Roman god of desire, eroticism, and affection, alluding to the tiny flowerheads, which resemble miniature shaving brushes. The specific name is derived from the Greek sonkhos, the ancient name for sow-thistles, and the Latin folium (‘leaf’). The leaves of this plant often resemble those of Sonchus oleraceus (see below). However, they vary tremendously, from lyrate and pinnatifid to almost entire.

Lilac tasselflower is very common in Taiwan, also in cities, in this case Taichung. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Erigeron Fleabane

A huge genus with around 400 species, widespread in Asia, Europe, and North America, and also a few species in Africa and Australia. These plants are very similar to some members of the well-known genus Aster, but ray florets are usually in 2 or several rows, and very narrow, as opposed to one row of broader florets in Aster.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek eri (‘early in the morning’) and geron (‘old man’), alluding to some species, which are covered with down when young. Some members of the genus contain an oil with a turpentine-like smell, which, supposedly, should deter fleas, hence the common name.

Erigeron annuus Annual fleabane

This species is native to North America, but has become naturalized many other places, especially Europe and Asia. It is a pioneer plant, often colonizing disturbed areas, including fallow fields, waste places, roadsides and along railways.

Annual fleabane, Nyborg harbour, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Erigeron canadensis Horsetail fleabane

This plant is also known as Canadian fleabane, and some authorities regard it as belonging to the genus Conyza. It is native to North America and parts of Central America, but has been accidentally introduced to large parts of the world. In many places it has become a serious pest, especially in Europe and Australia, but also in its native North America. It prefers to grow in undisturbed areas and is particularly troublesome in newly established plantations, where it is able to resist herbicides, growing to 3 m tall, thus depriving planted species of nutrients and sunlight.

This plant contains an oil with a turpentine-like smell, which, supposedly, should deter fleas, hence its common name. Another popular name is bloodstanch, given by herbalists, who claim that an extract from leaves and flowers arrests haemorrhages from the lungs and alimentary tract.

Horsetail fleabane, growing at the edge of a drainage canal in the city of Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Here, horsetail fleabane has sprouted in a crack along a street in Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This horsetail fleabane, observed in a graveyard in Taichung, is almost 2 m tall. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Horsetail fleabane, growing along a house wall, Ørbæk, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Erigeron karvinskianus Mexican fleabane

This vigorous plant is native to Mexico, Central America, Colombia, and Venezuela, but has become naturalized in numerous other countries around the world, including parts of Europe, Africa, Australia, Chile, and the United States.

It has numerous stems, branching from a woody rootstock to a height of about 25 cm, often forming dense clumps, stems slender, furrowed, smooth or sparsely hairy. Leaves alternate, lower ones large, elliptic, lobed or toothed, upper ones smaller, linear or lanceolate, entire, toothed, or shallowly lobed. Ray florets, up to 80, are white, mauve, or pink, disc florets yellow.

The plant gives a pleasant smell when crushed.

The specific name refers to Bavarian naturalist Wilhelm Friedrich Karwinski von Karwin (1780-1855), who was born in Hungary, but worked in Germany. He collected plants and animals in Brazil and Mexico.

Large growth of Mexican fleabane on the stairs, leading up to the church Notre Dame de Roscudon, Pont-Croix, Brittany. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mexican fleabane, growing in cracks between stepping stones, St. Malo, Brittany. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this picture, Mexican fleabane grows on one of the many stone bridges in Brugge, Belgium. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mexican fleabane, growing in a crack in a wall along a canal, Brugge. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Galinsoga

This genus has between 15 and 33 species, native to the Americas. Some species have been spread almost worldwide.

The genus was named in honour of Ignacio Mariano Martinez de Galinsoga (1756-1797), director of the Royal Botanical Garden in Madrid, and physician to the Spanish Queen consort Maria Luisa de Parma. In Britain, the generic name was corrupted to gallant soldiers.

Galinsoga parviflora Hairy galinsoga, gallant soldiers

This herb, which is native to South America, was brought from Peru to Kew Botanical Gardens, London, in 1796. Later it escaped, quickly forming wild populations, and today it has been spread to most parts of the world, growing in waste areas, fields, gardens, along trails, and in cities.

The stem is branched, sometimes growing to 75 cm tall, but usually much lower. The leaves are opposite, stalked or sessile, broadly lanceolate, to 11 cm long and 7 cm wide, margin weakly toothed. The flowerheads are tiny, to 5 mm across. The ray florets, usually 5, but sometimes up to 8, are usually white, sometimes pink, 3-lobed, to 1.8 mm long and 1.5 mm wide, disc florets yellow.

Leaves, stem and flowers are edible, and the subtle flavour, reminiscent of artichoke, develops after being cooked. It is also dried and ground into powder for usage in soups. In Nepal, juice of the plant is applied to wounds.

Hairy galinsoga, growing next to house walls, Kathmandu, Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gnaphalium Cudweed

A genus with about 38 species, distributed in subarctic, temperate, and subtropical areas on all continents, except Antarctica.

The generic name is a Latinized form of Ancient Greek gnaphallion (‘a lock of wool’), referring to the woolly leaves of many of these plants.

Gnaphalium uliginosum Marsh cudweed

Marsh cudweed, sometimes called brown cudweed, is native to Europe and northern Asia, and it has been accidentally introduced in North America, where it is found in the northern half of the continent.

The natural habitat of this plant is humid areas, such as water-logged fields, but it is also able to thrive in drier areas, including city streets. In Russia, it has been used in folk medicine to treat high blood pressure.

The specific name is derived from the Latin uligo (‘dampness’), referring to the preferred habitats of this plant.

Marsh cudweed (the greyish-green plants), growing among cobble stones on a sidewalk, Jutland, Denmark, together with annual meadow-grass (Poa annua) and greater plantain (Plantago major, see Plantaginaceae below). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ixeridium

This genus with about 19 species is found from Pakistan eastwards along the Himalaya and southern Tibet to Korea and Japan, and thence southwards through Indochina and the Philippines to Java and New Guinea.

Ixeridium laevigatum

The basal leaves of this species are very variable, mostly with rather large lobes, but sometimes being almost entire, whereas the stem leaves are mostly linear and rather narrow. The yellow flowerheads are up to 1 cm across. It is distributed in Japan, China, Taiwan, Indochina, the Philippines, and Indonesia, growing in forests, shrubberies, and grasslands, up to an elevation of about 600 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘smooth’, presumably referring to the smooth stem.

In Taiwan, Ixeridium laevigatum is often encountered in urban areas. In this picture, it grows beneath a tree on a sidewalk in Taichung, together with lance-leaved mugwort (Artemisia lancea). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ixeris

This Asian genus, comprising about 19 species, is found from south-eastern Siberia and Kamchatka southwards to Borneo and New Guinea, westwards to Afghanistan and the Indian Subcontinent.

Ixeris chinensis Rabbit milkweed

This plant is easily identified by its mostly linear, rather narrow leaves and pale yellow flowerheads, to 2 cm across. It is distributed from south-eastern Siberia southwards through China, Korea, Japan, and Taiwan to Southeast Asia, growing commonly in a variety of habitats, including grasslands, forest margins, shrubberies, riverbanks, field margins, wastelands, and roadsides, up to an elevation of about 4,700 m.

As these pictures show, rabbit milkweed may sprout in small cracks in roads and sidewalks, and along house walls. – Taichung, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lactuca Lettuce

The number of species in this genus is unsettled. Many former members have been moved to other genera, and the genus is still being revised. It may have 50-70 members, mainly distributed in temperate areas of Asia, Europe, and North America.

The generic name was the classical Latin name of the garden lettuce (below), derived from lactis (‘milk’), alluding to the milky sap of this plant. The English name is a corruption of the Latin word.

Lactuca muralis Wall lettuce

This species, by some authorities called Mycelis muralis, is native to most of Europe, north-western Africa, and West Asia, eastwards to the Caucasus, where it may be found up to an altitude of 2,300 m. It has also become naturalized in North America and New Zealand.

The main habitat of this plant is woodlands, but it may also be found in open areas, including forest clearings, city walls, stone fences, and along railroads.

The specific name is derived from the Latin murus (‘wall’).

Wall lettuce, growing out from beneath a rhododendron bush, Vejle, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lactuca sativa Garden lettuce

Lettuce probably originated from a plant in Mesopotamia, but is not known in the wild today. At an early stage, it was farmed by the Ancient Egyptians, from where it spread to Greece and Rome. By 50 A.D., many types were known, and the species often appears in medieval writings.

Today, it is cultivated in most parts of the world, mostly as a leaf vegetable used in salads, and also for sandwiches and wraps. It can also be added to soups.

Garden lettuce, naturalized in a drainage canal, Taichung, Taiwan. The composite with white ray florets is downy bur-marigold (Bidens pilosa), see above. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lactuca serriola Prickly lettuce

This plant is named for the row of spines along the mid-vein on the underside of the leaves, and the leaf margins also have fine spines. The leaves are very variable, from entire to deeply divided. It is a tall plant, under favourable conditions growing to 2 m tall, with a slightly fetid smell.

It is native to Europe, North Africa, and temperate areas of Asia, and has also become naturalized elsewhere, growing along beaches, roads, and railroads, and as a field weed.

One folk name of prickly lettuce is compass plant. The leaves of its main stem are aligned north-south, offering the least surface area to the midday sun, but the maximum area to the weaker light early and late in the day.

Incidentally, this plant was named twice by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), in 1756 as L. serriola, and in 1763 as L. scariola, derived from the Latin escarius (‘edible’). The first name is probably a misspelling, which Linnaeus then corrected in 1763. However, according to the nomenclature rules, the first published name has priority.

The name scariola was used by Englishmen at least as far back as the 1400s. According to the Oxford Dictionary, one source said: “Wylde letus hat feldman clepyn Skariole.” (“Wild lettuce have field-men (farmers) called Skariole”).

In these pictures, prickly lettuce has sprouted among tombstones, Houdain, southwest of Lille, France. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Matricaria Chamomile, mayweed

A small genus with 6 species, widely distributed in the Northern Hemisphere.

The generic name is derived from the Latin matricis (’mother’s life’, i.e. the womb). Formerly another plant, feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium), was regarded as a species of chamomile, named Matricaria parthenium by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778). In Ancient Rome, feverfew was used for uterus problems.

Matricaria discoidea Disc mayweed

Disc mayweed is native to North America and north-eastern Asia, southwards to Hokkaido, Japan. Today, however, it has been accidentally introduced to most other areas of the world, where it is a common weed, growing in open areas. Other names of the plant include wild chamomile and pineapple weed, due to its chamomile- or pineapple-like smell, when crushed.

The specific name is derived from the Latin discoides (‘disc-shaped’), referring to the flowerheads.

Disc mayweed, growing in a crack along a gutter, Jutland, Denmark. The white object is a bird feather. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This large specimen of disc mayweed has sprouted between cobble stones, Nyborg, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Notobasis syriaca Syrian thistle

This extremely spiny plant, the only member of the genus, is native to the Mediterranean region and the Middle East, from Madeira, the Canary Islands, Portugal, and Morocco eastwards to Iran and Oman. It mainly grows in dry areas, including semi-desert.

It grows to about 1 m tall, leaves spirally arranged on the stem, deeply lobed, grey-green or dark green with white veins and very sharp spines on lobes and apex. Flowerheads to 2 cm across, bracts numerous, spiny, ray florets absent, disc florets reddish-purple.

In Crete, the tender shoots are peeled and eaten raw.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek notos (‘spine’ – anatomical) and vasis (‘base’), hence ‘based on the spine’. This strange name alludes to the compressed achenes attached by the base of their upper side. The specific name refers to Syria. Presumably, the type specimen was collected there.

This Syrian thistle has sprouted in a crack on a sidewalk, Cefalú, Sicily. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Parthenium

Members of this American genus, which contains about 12 species, are commonly known as feverfew, not to be confused with an Old World plant with the same name, Tanacetum parthenium, which is presented on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

The generic name is a Latinized version of the Greek parthenos (‘virgin’), or maybe parthenion, which was the name of an unknown plant in Ancient Greece.

Parthenium hysterophorus Santa Maria feverfew

This plant is native to large parts of the Americas, from southern United States southwards to Mexico, the Caribbean, and northern South America. However, it has been spread to virtually all warmer areas of the world and has become naturalized in many places, ranging from fields and grasslands to roadsides, fallow plots, and along railroads, usually below 1,500 m altitude, but occasionally observed up to 1,800 m. It is regarded as an invasive in Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania.

The stem grows to 1.2 m tall, leaves ovate or elliptic in outline, to 18 cm long and 9 cm wide, pinnately divided, ultimate segments lanceolate to linear, to 5 cm long and 1.5 cm wide. Flowerheads to 3 mm across, in open panicles, florets snow-white, ray florets tiny or missing. This plant somewhat resembles certain species of Artemisia (above), but its flowerheads are more flattened, and pure white.

In America, it has a number of popular names, including bitterweed, carrot grass, congress grass, false chamomile, false ragweed, and white-top.

The specific name is from the Greek hystera (‘womb’) and phoros (‘bearing’), maybe alluding to the shape of the flowerheads.

This plant should be handled with caution, as it may cause dermatitis and respiratory malfunction in humans, and, if eaten by livestock, it may cause udder disease.

An abundance of Santa Maria feverfew, growing in an empty lot, Kathmandu, Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this picture, Santa Maria feverfew grows along a busy street in Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Santa Maria feverfew, Taichung. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Inflorescences of Santa Maria feverfew, Taichung. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The leaves of Santa Maria feverfew resemble those of certain species of Artemisia (see above). – Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Senecio Groundsel, ragwort, butterweed

This huge genus, comprising more than 1,200 species, is found almost worldwide. The majority of these plants are erect herbs, with a few climbing or scrambling species.

The generic name is derived from the Latin senex (‘old man’), alluding to the white seed hairs of the genus.

Senecio inaequidens Narrow-leaved ragwort

This plant, also known as South African ragwort, is native to southern Africa, but since the 1970s it has spread to almost all countries in Europe, accidentally introduced through wool imports from southern Africa. Recently, it has also been reported from many other parts of the world, often regarded as an invasive plant that dispels native species.

In its native area, this species grows in a wide variety of disturbed habitats, including heavily grazed or recently burned grasslands, roadsides, and river banks, from sea level to altitudes around 2,850 m. In Europe, it is mostly found along highways and railways.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with unequal teeth’, alluding to the unequal teeth along the leaf margin.

Narrow-leaved ragwort, growing on a pier in the city of Enkhuizen, Holland. An old sailing ship is anchored at the pier. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Senecio viscosus Sticky groundsel

As its name implies, this plant, also called sticky ragwort or stinking groundsel, is very sticky. The following quotation gives a vivid impression of its stickiness: “Sticky groundsel has characteristic glandular hairs, which secrete a substance that is as sticky as fly paper, and by the end of summer it is quite a mess with all the dust, sand, small insects, hairs, feathers, downy seeds, its own cypselas [seeds], candy wrappers, and who knows what else that have stuck to it.” (Source: luontoportti.com/suomi/en/kukkakasvit/sticky-groundsel)

Originally, sticky groundsel was a native of southern and central Europe and western Asia. Since the 1800s, it has spread considerably, mainly along railroads, and has become naturalized in northern Europe, Canada, United States, and elsewhere.

Sticky groundsel, Nyborg harbour (top), and Aarhus Railway Station, both Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Senecio vulgaris Common groundsel

This species is found in a vast area, from the entire Europe eastwards to eastern Siberia, southwards to northern Africa, Arabia, Iran, southern China, and Taiwan, growing in disturbed habitats, and very often seen in cities.

It is a slender plant, sometimes growing to 40 cm tall, but usually lower. It resembles sticky groundsel, but lacks the ray florets and the glandular hairs.

Common groundsel, growing at a house wall, Malestroit, Brittany. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sonchus Sow-thistle

This genus, comprising about 100 species, is widely distributed in the entire Old World, and has also become widely naturalized in the New World.

The generic name is a Latinized form of the Greek sonkhos, the ancient name for sow-thistles.

Sonchus arvensis Corn sow-thistle

As its name implies, this plant is a weed in fields. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘growing in fields’, derived from arvus (‘cultivated’). It is also found in other open areas, including pastures, beaches, and along rivers and roads. It is native in a vast area, from the entire Europe eastwards to the Pacific Ocean, southwards to the Mediterranean, Turkey, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, and Ussuriland in south-eastern Siberia. It has also become naturalized in many other areas, and is regarded as a noxious weed in North America, New Zealand, and Australia.

It grows to about 1.5 m tall, lower leaves alternate, to 35 cm long and 14 cm wide, lobed, with fine teeth along the margin, leaves getting gradually smaller up the stem. The flowerheads are yellow, to 5 cm across.

Corn sow-thistle, Nyborg Harbour, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sonchus asper Prickly sow-thistle

A stout plant, which may grow to 1.2 m tall, but is often much lower. The stem is often reddish. Leaves are extremely variable, obovate, spatulate, or elliptic, to 13 cm long and 5 cm wide, entire or irregularly divided, base eared and strongly recurved, clasping the stem, margin heavily spiny. Flowerheads relatively few, to 2.5 cm across, in an open terminal cluster. Ray florets numerous, bright yellow, disc florets absent.

This species presumably originates from the Mediterranean region, but has become naturalized in most parts of the world. In Nepal, a paste of the plant is applied to wounds and boils. It is also collected for fodder, and tender parts are cooked as a vegetable.

In the picture below, prickly sow-thistle is growing in front of a tombstone in the Assistens Cemetery, Copenhagen, placed on the grave of Thorkild Weiss Madsen, who was active in the alternative-lifestyle area of Christiania (described on the page Culture: Folk art around the world.) The stone is shaped as a runic stone with a carved dragon and the following text (approximate translation): ”This stone was erected in memory of Thorkild by his wife and daughter. The good boy Eric the Red carved the runes.”

(Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sonchus oleraceus Common sow-thistle

This species is native to Europe and western Asia, but has been spread to most other areas of the world. It is regarded as an invasive plant in many countries, including Australia, where it is a serious problem in crops. It is easily identified by its slightly prickly, deeply divided leaves.

The specific name is derived from the Latin oleris, meaning ‘edible’. Young leaves can be eaten as salad or cooked like spinach. The common name refers to the fact that pigs like to eat this plant, and to the leaves, which resemble young thistle leaves.

Common sow-thistle is very common in Taiwan. This picture shows a large growth in the city of Taichung. The white flowers are downy bur-marigold (Bidens pilosa, see above). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one has taken root along a house wall in the town of Rønne, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Common sow-thistle, peeping out through a garden fence, Terrasini, near Palermo, Sicily. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This common sow-thistle has sprouted in a crack along a parking lot, Taichung, Taiwan. Tree sparrows (Passer montanus) are eating its seeds. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hybrids between prickly and common sow-thistle, Taichung. The spines on the leaves indicate prickly sow-thistle, whereas the deeply divided leaves, and the pointed ‘ears’ at the nodes, indicate common sow-thistle. The composite with white ray florets is downy bur-marigold (Bidens pilosa), described above. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sonchus tenerrimus Slender sow-thistle

This plant is native to southern Europe, northern Africa, and western Asia, but has been spread to many cities around the world, the seeds presumably arriving with ship cargo. It resembles the common sow-thistle (above), but may at once be identified by its deeply divided leaves, with very narrow lobes.

Slender sow-thistle, growing at a house wall, Castellamare del Golfo, Sicily. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sonchus wightianus

This plant resembles the previous species, but may at once be identified by the leaves, which are usually undivided, sometimes lobed, the margin with few or many sharp teeth. It grows to 1.5 m tall, but is often much lower. The flowerheads are to 1.5 cm across.

It is distributed from Afghanistan eastwards to China, thence southwards to Sri Lanka and Java, growing in open areas, waste lands, fallow fields, and urban areas, from the lowlands to elevations around 2,300 m.

The specific name was given in honour of Scottish surgeon and botanist Robert Wight (1796-1872), who spent most of his life in southern India, where he was the leading botanical taxonomist, describing 110 new genera and 1,267 new species. He published a series of illustrated works in Madras, including the six-volume Icones Plantarum Indiae Orientalis (1838–53), the Illustrations of Indian Botany (1838–50), and Spicilegium Neilgherrense (1845–51).

Sonchus wightianus, Sundarijal, Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Galinsoga parviflora is also seen. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sonchus wightianus, growing up a fence, Hanoi, Vietnam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Symphyotrichum American aster

A large genus with about 100 species, formerly included in the genus Aster. These plants are distributed in the Americas, and in central and eastern Asia.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek symph (‘come together’) and trich (‘hair’), alluding to the woolly anthers, which resemble a tuft of hairs.

Symphyotrichum subulatum Eastern saltmarsh aster

This species, formerly known as Aster subulatus, is native to eastern North America, Texas, northern Mexico, and some islands in the Caribbean, but has become naturalized in many other warmer areas around the world.

The stem grows to 1.5 m tall, leaves dark green, narrowly linear, with entire margin. The inflorescence is a raceme with numerous small flowerheads, to 1 cm across, disc florets yellow, ray florets varying in colour from white to lavender. It grows in a wide variety of habitats, including salt marshes, lawns, empty plots, and along ponds, fields, and roads.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘awl-shaped’. It is not clear what it refers to.

Eastern saltmarsh aster, Mandzou, southern Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this picture, eastern saltmarsh aster grows near a house wall in Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tanacetum Tansy

This genus, comprising about 100 species, is distributed in Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia, and northern North America. About 36 species, which were formerly placed in this genus, have been moved to the genus Ajania.

Disc florets are yellow, whereas ray florets are missing in most species. When present, they are mostly white.

The generic name is Latin, adapted from Ancient Greek athanatos (‘immortal’), probably referring to the persistence of these plants. The common name was adapted from Old French tanesie, a corruption of the Latin name.

Tanacetum partheniifolium

There is much confusion regarding the difference between this species and the well-known garden plant feverfew (T. parthenium), which probably evolved through selection from T. partheniifolium. The leaves of the latter are dark green or grey-green, with a pointed outline, whereas they are pale green and has a rounded outline in feverfew. Otherwise they are very similar.

Stems single or up to 3 together, to 80 cm tall, erect, branched, ridged. Leaves are mainly stalked stem leaves, once or twice pinnately lobed, to 10 cm long and 4 cm wide. Flowerheads 5-20, sometimes more, in an umbel-like cluster, involucre to 7 mm across, ray florets 10-20, white, to 1.2 cm long, disc florets yellow, to 2 mm long.

T. partheniifolium is native from Turkey and Ukraine eastwards to Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and northern Iran, mainly growing in dry or sandy areas, from sea level up to elevations around 2,000 m.

The medicinal properties of feverfew are discussed on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Tanacetum partheniifolium is very common in Istanbul, even on buildings. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Taraxacum Dandelion

Apomictic (asexual) reproduction is very common in dandelion, resulting in an abundance of species and micro-species, more than 2,500 worldwide, mainly in subarctic and temperate zones of the Northern Hemisphere, a few in temperate regions of the Southern Hemisphere.

These plants are characterized by stem and leaves having a milky sap, and most species have lobed or serrated leaves. The single flowerhead, 2-6 cm across, is borne on a leafless, hollow stem, 10-20 cm tall, sometimes more. Florets are yellow, very numerous, densely crowded.

Dandelion was first mentioned as a medicinal herb by Arabian physicians in the 10th or 11th Century, who called it a sort of wild endive (Cichorium), under the name of tharakhchakon, which was corrupted to Taraxacum. In French, these plants were named dent de lion (‘lion’s tooth’), alluding to the often strongly serrated leaves. This name was adopted by the English, corrupted to dandelion.

The role of dandelion in folklore and traditional medicine is described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Taraxacum officinale Common dandelion

This species is a native of the Northern Hemisphere, but has become naturalized in countless countries around the globe. It is ubiquitous in Europe, including in cities, where it readily grows in cracks and between flagstones.

Large growth of dandelion along a highway, Århus, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In these pictures from Copenhagen, Denmark, dandelion grows among wood chips, strewn along a street (top), and outside the Carlsberg Breweries. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tridax

This is a genus of Latin American plants, comprising about 34 species, distributed from Mexico southwards to northern Argentina.

The generic name is Ancient Greek, presumably referring to the 3-toothed ray florets of lantern tridax (below).

Tridax procumbens Lantern tridax

This small composite, which is native to Tropical America, has been introduced to most warmer areas of the world and has become naturalized in many places.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘prostrate’.

Lantern tridax is extremely common in Taiwanese cities, sprouting in cracks everywhere and often covering large areas. These pictures are all from the city of Taichung. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Here, lantern tridax has sprouted in a crack in a concrete wall along the Han River, Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lantern tridax, growing near a metal sheet wall, Taichung. The tall plant is a species of aster, Symphyotrichum subulatum (see above). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this picture, lantern tridax has sprouted on a grass-clad grave in Taichung. The plant with white flowerheads is downy bur-marigold (Bidens pilosa, see above). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Youngia

A genus of Asiatic composites, counting about 44 species, found from Uzbekistan and Afghanistan eastwards to Japan, southwards to Sri Lanka, the Malayan Peninsula, and the Philippines.

When French botanist Alexandre Henri Gabriel de Cassini (1781-1832) named the genus in 1831, he wrote that the name honoured two Englishmen named Young: “deux Anglais célèbres, l’un comme poète, l’autre comme physicien.” The first may have been poet and dramatist Edward Young (1683-1765), and the other may have been Thomas Young (1773-1829), a multifarious scientist and physician.

Youngia japonica Oriental false hawksbeard

The stem of this plant, which is also known as Japanese hawksbeard, is usually tall, erect, and unbranched, with numerous small, yellow, terminal flowerheads, to 8 mm across. The basal leaves are quite broad, more or less hairy, and mostly deeply lobed or pinnately divided.

It is native from Afghanistan eastwards to Japan, southwards to Sri Lanka, the Malayan Peninsula, and the Philippines, but has spread to most warmer areas of the world. It is common in disturbed areas, wastelands, roadsides, abandoned pastures, lawns, cultivated fields, and forest margins.

Oriental false hawksbeard thrives under tree cover. This picture shows a large growth in a green spot between streets, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In cities, oriental false hawksbeard is mostly found in parks. These pictures are from Tunghai University Park, Taichung. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Boraginaceae Forget-me-not family

A huge family, comprising about 156 genera with c. 2,500 species of herbs, rarely shrubs, climbers, or trees. Most species are bristly-hairy. These plants are distributed in temperate, subtropical, and tropical regions, with a core area around the Mediterranean.

The family was named after the borage (Borago officinalis), native to the Mediterranean area and widely cultivated as a food plant and an ornamental. The popular name of the family is explained on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Anchusa Bugloss, alkanet, ox-tongue

This genus contains about 38 species, native from Europe and North Africa eastwards to the Ural Mountains, Mongolia, and northern China, and also in Ethiopia and southern Africa.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek ankhousa, the name of Alkanna tinctoria, which was used as a cosmetic. The name bugloss stems from Ancient Greek bouglosson, the name of Anchusa azurea, from bous (‘ox’) and glossa (‘tongue’), referring to the leaves, which are shaped like an ox-tongue and have a rough surface – just like the tongue of an ox.

Anchusa officinalis Common alkanet

This species, also known as common bugloss, probably originates from the Mediterranean area or western Asia, but was spread to the major part of Europe at a very early stage. Today, it ranges from Scandinavia and France eastwards to the Ural Mountains, Kazakhstan, and Turkey, and it has been introduced to North America, where it is regarded as a noxious weed in many places. It grows in disturbed habitats, often along roads, and in fallow fields and waste ground.

The small flowers are tubular, to 1.2 cm across, petals 5, fused, corolla initially reddish-brown, later changing colour to dark blue or purple.

The plant was formerly cultivated for its edible leaves, and for the root, which was used as a dye and as a folk medicine. Originally, the name officinalis was derived from officina (‘workshop’, or ‘office’), and the suffix alis, which, together with a noun, forms an adjective, thus ‘made in a workshop’. However, in a botanical context, the word denotes plants species that were sold in pharmacies due to their medicinal properties.

Common alkanet, Glömminge, Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cerinthe Honeyworts

A small genus with 6 species, found from central and southern Europe eastwards to Kazakhstan, and in the Middle East and northern Africa. These plants are unusual members of Boraginaceae, as all parts are smooth. Most members of the family are very hairy.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek keros (‘wax’) and anthos (‘flower’). It was once believed that bees got wax for their hives from these flowers.

Cerinthe major Greater honeywort

This plant is native to countries around the Mediterranean, growing in open, grassy areas. It is very variable, having green, bluish-green, or purple bracts beneath the colourful flowers, which may be yellow, yellow with brownish base, or purple. It is usually below 60 cm tall, but may grow to 1 m under favourable conditions.

It is divided into 3 subspecies, major, which is widespread around the Mediterranean, oranensis of northern Africa, and purpurascens, which is restricted in the wild to southern Spain, but is widely cultivated elsewhere.

Escaped greater honeywort, ssp. purpurascens, Dinan, Brittany. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Echium Viper’s bugloss

A genus with about 68 species, distributed from the Azores, Madeira, the Canary Islands, and the Cape Verde Islands eastwards to central Siberia and Xinjiang, and from Scandinavia and Finland southwards to northern Africa, Arabia, and Iran. No less than 29 species are endemic to the Macaronesian islands. Members have also become naturalized in many other places, including North America, southern South America, Australia, and New Zealand.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek echis, meaning ‘viper’. Greek physician, pharmacologist, and botanist Pedanius Dioscorides (died 90 A.D.), author of De Materia Medica, 5 volumes dealing with herbal medicine, noted the resemblance between the shape of the nutlets and a viper’s head. The long stamens, sticking out of the flower, also resemble a viper’s tongue. The name bugloss is explained above at Anchusa.

Formerly, it was believed that these plants could be used as a cure for snake bite. British herbalist Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654) says: “It is a most gallant herb of the sun; it is a pity it is no more in use than it is. It is an especial remedy against the biting of the viper, and all other venomous beasts, or serpents; as also against poison, or poisonous herbs. Dioscorides and others say that whosoever shall take of the herb or root before they be bitten, they shall not be hurt by the poison of any serpent.”

Echium vulgare Common viper’s bugloss

Common viper’s bugloss is native to most of Europe and northern Temperate Asia, and it has also become naturalized in parts of North America.

Among American indigenous peoples, a decoction of the plant was taken in case of ’white urine’, indicating too much calcium in the urine.

In Swedish, the name of this species is blåeld, meaning ‘blue fire’, alluding to the wonderful blue colour of the flowers, which, when many plants grow together, does resemble ‘blue fire’.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘common’.

Common viper’s bugloss, Glömminge, Öland, Sweden. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Brassicaceae (Cruciferae) Cabbage family

A huge family of herbs and some shrubs, with about 330 genera and c. 3,500 species, found in all continents, except Antarctica, mainly in temperate areas. The highest diversity is around the Mediterranean, in the Middle East and Central Asia, and in western North America.

Petals are always 4 in number, arranged cross-wise, which has given rise to the alternative family name Cruciferae, from the Latin crux (‘cross’) and ferae (‘bearing’). The fruit is a carpel, which, at maturity, splits into two valves, either less than 3 times as long as broad (a silicula), or more than 3 times as long as broad (a siliqua).

A very difficult family, in which ripe fruits are often necessary for identification.

Capsella

A small genus with about 7 species, native to Europe, northern Africa, and western Asia.

The generic name is Latin, meaning ‘a little box’, referring to the fruit, which resembles a small bag.

Capsella bursa-pastoris Shepherd’s purse

The place of origin of this plant is probably western Asia and Europe, but it has become naturalized almost worldwide in temperate and subtropical areas. It grows in open areas, including fields, villages, cities, and along trails and roads, in Central Asia found up to elevations around 4,500 m.

A very variable plant, sometimes to 70 cm tall, but often much lower, stem erect, smooth or sparsely hairy, often branched. Basal leaves in a rosette, stalked, oblong or oblanceolate, to 10 cm long and 2.5 cm broad, base wedge-shaped, margin usually deeply dissected, but sometimes entire or variously toothed, tip pointed. Stem leaves are stalkless, lanceolate or linear, to 5.5 cm long and 1.5 cm broad, clasping the stem, margin entire or toothed. Inflorescences are terminal or axillary, many-flowered, to 30 cm long in fruit. Petals are usually white, but sometimes pinkish or yellowish, obovate, to 5 mm long and 1.5 mm broad.

The fruit is flat, inverted triangular, to 9 mm long and 6 mm broad. Its shape has given rise to the specific name bursa-pastoris (‘purse of a shepherd’), and to many of the popular names of the plant, including shepherd’s purse, lady’s purse, witches’ pouches, rattle pouches, case-weed, and mother’s heart.

An Irish name of the species, clappedepouch, was likewise given in allusion to the long-stalked siliques, which resemble a beggar’s cup. In the old days, lepers would ring a bell, or a clapper, receiving their alms in a cup at the end of a long pole, to avoid people being infected.

In Nepal, tender parts are cooked as a vegetable, and the seeds are used to kill mosquito larvae.

The role of shepherd’s purse in folklore and traditional medicine is described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Shepherd’s purse, growing in a crack along a sidewalk in Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Large growth of shepherd’s purse in Tunghai University Park, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this picture, shepherd’s purse grows in a gutter together with annual meadow-grass (Poa annua), Mineo, Sicily. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lepidium Cress, peppercress, pepperweed

A huge genus with about 260 species of herbs, rarely shrubs or climbers, found across the globe, except polar regions and some tropical areas.

The generic name is the classical Greek word for dittander (L. latifolium).

Lepidium ruderale Roadside pepperweed

This plant is native to temperate areas of Eurasia, eastwards to eastern Siberia, southwards to the Mediterranean, Iran, Xinjiang, and northern China, but has also become accidentally introduced to many other areas around the world. As its name implies, it grows in waste places, and is also found in fields, gardens, and along streets and roads.

Stem erect or ascending, many-branched, to about 35 cm tall, basal leaves forming a rosette, pinnately divided, to 5 cm long, lobes usually entire, rarely toothed. Stem leaves are sessile, linear, to 3 cm long and 3 mm wide, base cuneate, margin entire. Inflorescences are many-branched racemes, usually with an abundance of tiny flowers, petals usually white, sometimes yellow or pink, to 0.5 mm long. Fruits are ellipsoid, to 2.5 mm long and 2 mm wide, winged.

The leaves are edible when young. Medicinally, the plant has been used to treat skin disease, and a decoction to lower blood pressure and reduce respiration.

Roadside pepperweed, growing at a house wall, Brugge, Belgium. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Roadside pepperweed, Nyborg harbour, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lepidium virginicum Virginian peppercress

The common names of this species, which also includes least pepperwort, stem from the fact that all parts of this plant have a peppery taste. It resembles the previous species, but is larger, to about 70 cm tall, and it does not have a basal leaf rosette. The stem leaves are larger, to 15 cm long.

It is a native of North America, from southern Canada southwards to Mexico, but has been widely introduced to many other countries. It grows in open, drier places, and has readily adapted to a life in cities.

When the British colonized eastern America, they named the colony Virginia. When early botanists gave a plant the specific name virginicum, it applied to a much larger area than the present state of Virginia.

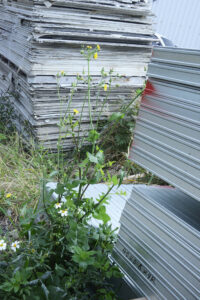

This Virginian peppercress has sprouted in a crack in an abandoned parking lot in the city of Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sisymbrium

A genus with about 48 species, native to almost the entire Eurasia and Africa, except arctic and tropical regions, and it is also native to western North America.