Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Malawi 1997: A three-day ferry cruise on Lake Malawi

The first European to see this lake was the Scottish missionary and explorer David Livingstone, in 1859. He named it Lake Nyasa.

A Christian mission was established near Cape Maclear, in the south-western corner of the lake, as early as 1875, but it was abandoned a few years later, as the missionaries died of malaria. Another mission, called Livingstonia, was established in the high, malaria-free mountains northwest of the lake. The work of the missionaries was very efficient indeed, and today almost the entire population of Malawi are Christians.

Ilala’s sister-ship, the M/V Mtendere, takes over, when Ilala has to be overhauled, and vice versa. If both ships are navigable, there are two weekly departures, one going all the way up to Tanzania in the northern end of the lake.

On board the Ilala are seven First-Class cabins on the upper deck (of which only one has attached bathroom). The rest of the First-Class passengers must spend the night in the open. Most passengers travel on Second Class, on the lower deck, which is rather crowded. The ferry can carry a total of 500 passengers.

Shortly after our departure, the ship comes to a stop. A passenger (presumably a VIP) has missed the ferry, and one of the Ilala’s small motor boats, attached to the side of the ferry, is sent ashore. When it returns, the ship glides out between the rocks, bound for the village of Chilinda, on the eastern lake shore.

The Ilala anchors some distance from the shore, whereupon its two motor boats are lowered into the water. Passengers jump into the boats, bringing all sorts of luggage, including suitcases, boxes, huge bunches of unripe bananas, flower-pots, and cages containing chickens or ducks, tied together by the legs, two or more in a bundle.

The boats depart in a dense cloud of diesel smoke, only to return a little later with new passengers. Several trips must be made, before all passengers, bound for this village, have been brought ashore. Some passengers are picked up by small canoes.

Other canoes approach the ship, loaded with mangoes, and a furious haggling over the price begins. When the two parties have come to an agreement, the fruits are handed up, and coins are tossed into the canoe.

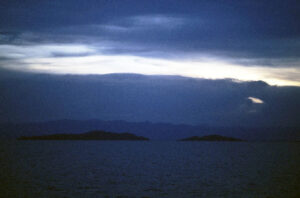

At dusk, gigantic black clouds, with lightning and thunder, pass over Cape Maclear. The storm approaches the ferry which, in this type of weather, is not able to go alongside the quay in Chipoka, but is forced to anchor offshore.

Heavy rain is pouring, and enormous gusts of wind cause the ship to roll. Without pause, the sky is illuminated by lightning. In this inferno, the crew is trying to get people into one of the motor boats, which is thrown back and forth by the waves, hitting the side of the ship with a tremendous crash. The crew members try to hold the boat close to the ship, while people, drenched to the skin, jump into it, risking being crushed between the ship and the boat. People shout and scream, babies cry on their mother’s back, and luggage is thrown helter-skelter into the boat, where people tumble about, trying to get foothold. Amazingly, nobody is hurt.

The boat is only half loaded before taking off towards the shore to await more suitable weather conditions. And soon the rain diminishes, the gusts of wind are less fierce, and the lightning ceases. The passengers on the upper deck are drenched to the skin, and they face a very uncomfortable night. I am happy that I was able to seek shelter in my tiny cabin during the worst part of the storm.

In the dark night, the ship heads north. At dawn, the weather is pleasant, although the waves are still quite high. We approach the village of Nkhotakota, named after the numerous sand bars found in this part of the lake. Drumbeats announce that breakfast is served on First Class. The rolling ship causes a single passenger to lose his appetite, and he must leave the table before getting his fill.

The present population of these tiny islands numbers about 5,000 souls, and they bear the stamp of a long period of overuse. Apart from a few fat baobabs, there is hardly a wild tree left on the islands. They have all been cut down to supply timber or firewood, or wood for smoking fish. Recently, a number of eucalyptus trees have been planted to supply firewood, but not nearly enough to meet people’s need.

The pride of Likoma is its great cathedral, an imposing building, which was inspired by the cathedral in Salisbury, England, and almost as large. Construction began in the late 1800s and was completed in 1911. It is beautifully crafted in stone and has fine stained-glass windows, depicting the twelve apostles and other subjects. I find the new roof ugly.

A great building like this seems rather out of place on this tiny island, perhaps fulfilling the ambitions of a bishop rather than the need of the inhabitants.

The cemetery is unique. Because of the rocky surface of the island, most graves are above ground, covered by numerous small rocks, sometimes with a stone or iron cross squeezed between the stones.

White-breasted cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo ssp. lucidus) rest on rocks around the island, but out on the lake proper, birds are surprisingly scarce. I only observe a few grey-headed gulls (Chroicocephalus cirrocephalus) and white-winged terns (Chlidonias leucopterus). Nile crocodiles (Crocodylus niloticus) should occur around the islands, but I fail to observe any.

When I get up at 5 a.m., it is still raining. We are now anchored some distance from the village of Mangwina, which is surrounded by forest-clad mountains, partly hidden behind clouds.

Whereas the landscape around the eastern and southern lake shores mainly consists of low, rolling hills, steep mountains rise several hundred metres along the north-western shore, between Nkhata Bay and Mlowe. These mountains are densely inhabited, and most villages are situated along the numerous small streams, which make their way down to the lake.

Only the most inaccessible parts of the mountains are still forest-clad. Elsewhere, the forest has been cleared for timber and firewood, and fields now stretch most of the way up the slopes. A depressing sight, but only too common throughout the Tropics.

This area is almost devoid of roads. Narrow and winding, one road leads from Mzuzu across the mountains, then steeply down the slope, through a number of hairpin bends, ending abruptly at the village of Usisya. Most villagers here connect with the outside world via one of the ferries, or in small canoes. If you don’t own a canoe, you must hike up steep trails to reach the road, where you can continue your journey by bus.

A beautiful red-and-white fish-eagle (Haliaeetus vocifer) is soaring over the lake, near the shore. It suddenly plunges into the water, emerging with a fish in its talons, while its mate, sitting in a nearby tree, emits a penetrating call.

North of Mlowe, the mountains retreat inland, and sand bars stretch far into the lake. In the afternoon, we reach the harbour in Chilumba. My three-day trip on Lake Malawi has come to an end.