Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

India 2003: Camel safari in the Thar Desert

The fruit of Sodom apple was first described by Roman historian Titus Flavius Josephus, born Yosef ben Matityahu (c. 37-100 A.D.), who found it growing near the city of Sodom: “which fruits have a color as if they were fit to be eaten, but if you pluck them with your hands, they dissolve into smoke and ashes.” (Source: W. Whiston 1737. The War of the Jews, Book IV, Chapter 8)

Titus is referring to the fact that the ripe fruit easily dissolves, releasing hundreds of downy seeds, which are scattered to the four winds.

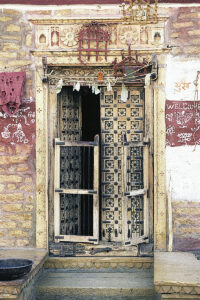

Scattered across the bleak landscape lie numerous towns and villages. One such town is Jaisalmer, close to the Pakistani border, which was founded in 1156 by a Rajput prince, Roa Rawal Jaisal. As many of its buildings are constructed of golden-yellow sandstone, it has been dubbed ‘The Golden City’.

During the era of the great trading caravans, a side branch of the Old Silk Road led through this town. Travelling along this route, numerous camel caravans brought goods to and from India, trading with faraway China, Persia, Turkey, and Europe. As wealth accumulated in Jaisalmer, rich traders built extravagant and ornate sandstone mansions, called havelis, their walls and balconies decorated with beautiful and detailed carvings.

Wealth, however, also attracts robbers, so in order to protect his people, Roa Rawal Jaisal ordered a strong fort, Sonar Qila, to be constructed atop a 76-metre-high hill. The population was then moved inside the walls of the fort, which was fortified with 99 ramparts. Large stone balls and long stone cylinders were placed on the walls, and during sieges, Rajput soldiers would roll these balls and cylinders over the edge, causing many casualties among attackers, who attempted to scale the walls of the fort. Still today, some of these balls remain on the walls.

As the population of Jaisalmer increased, people began building houses outside the fort, so as a means of protection, the Rajput prince ordered a wall, 4.5 km long, to be erected around this new part of the town.

K.K. himself has had a fair share of problems. He and his brothers own a rather large piece of farmland, but his brothers neglect it, leaving it to K.K. to earn money for the entire family through his travel agency. He has paid their wedding expenses, and also contributed half a million Rupees to their farming, which, however, did not result in an increased production. K.K. is bitter, calling his brothers a bunch of good-for-nothing parasites.

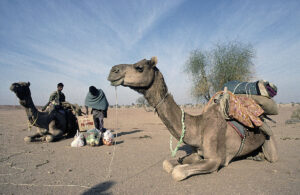

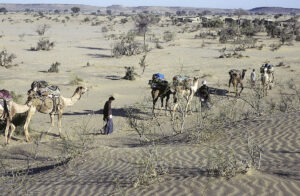

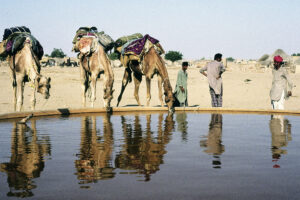

Arriving at Akal, we meet with my two camel drivers, Jamset and Dina Khan, and their three camels, which look rather arrogant, but turn out to be gentle and peaceful animals, with large and beautiful eyes. In winter, when she camels are in heat, bulls in rut often emit a gargling roar, blowing up their tongue and letting it hang out of the mouth, smeared in pink saliva. My camel drivers make this comment: “The camel is sexy.”

The first time you mount a camel, you are in for a surprise. When a camel gets up, its legs are unfolded in several tempi. First, it rises halfway on its hindlegs, and you are thrown forward. Next, it rises on its forelegs, and you are thrown backward. Finally, it rises completely on its hind-legs, making you slide forward again. If you don’t have a firm grip on the saddle, you may easily fall off.

Camels have an ambling walk, which takes time to get used to. On my first day as a camel rider, my thighs and buttocks quickly get quite sore. I regularly dismount to take pictures, often walking beside the camel for hours.

“Grandfather galloping same horse!” says Dina.

Shortly before dusk, we make camp. The baggage is unloaded, and our blankets are rolled out in the sand. No need for tents here, as the risk of rain is next to none. However, nights in the desert are rather cold, so my sleeping bag is of good use.

Jamset and Dina collect a few dead branches from nearby trees, light a fire and start preparing our evening meal. Meanwhile, I am seated, leaning against a camel’s soft body, watching the flickering fire, while the camels are chewing their cud, their neck bells tinkling softly. While cooking, my camel drivers sing sad songs about love or precious rain.

The night is wonderful. To lie snug in your sleeping bag on the soft desert sand, under a thousand twinkling stars, and maybe a falling star or a moving satellite, is indeed meditative.

The commonest mammal is the Gujarat gazelle (Gazella bennettii ssp. christii), locally known as chinkara. On several occasions, I also encounter the desert fox (Vulpes vulpes ssp. pusilla), of which one is eagerly digging in the sand for mice, or maybe beetles.

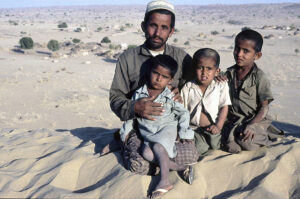

As it turns out, their village, Bambara, comprising about twenty houses, is situated at the end of a valley, beneath marvellous sand dunes. Most houses are made of clay, which has been applied to a frame, constructed of branches. Before the clay dried, the women drew fine patterns, trees and other images in it. The roof is made of straw. In front of every house is a courtyard, worn smooth by many feet. At one end of the village sits the school – an ugly concrete building, which seems out of place among the beautiful clay houses.

We camp in the dunes outside the village, where we are soon joined by many men and children. We invite them for supper, which makes heavy inroads into our provisions. However, Jamset assures me that we have ample supplies, and besides, K.K. has given him extra money to buy more provisions.

After the meal, an elderly man entertains us, singing sad songs, as usual about love and precious rain, but also a song about a brother, who was lost in war. Next, a young man performs a wild dance, with much gamboling, while a boy beats the time on a tin tray.

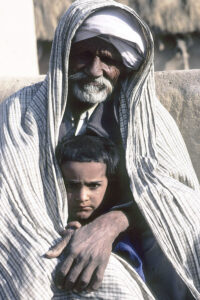

The following morning, I pay a visit to several houses in the village. All inhabitants are more or less blood-related, and marriages outside the village are rare. However, apart from a young man who is an albino, I see no sign of inbreeding. On the contrary, the villagers are beautiful and erect people. Presumably, the hard desert life sorts out the weak ones.

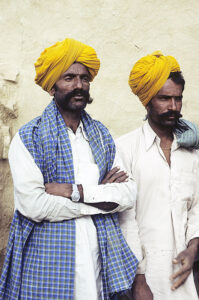

Many of the men sport a full beard, looking rather like Baluchis from western Pakistan. They do not grow the enormous ’cycle-handle’ moustache, which is so popular among the Hindu Rajputs. The women’s dress is very beautiful, the upper half a patchwork of bits of cloth, silver, and small, glittering buttons. Around their wrist – and sometimes also their neck – they wear heavy silver jewellery.

One of Jamset’s camels, its forelegs tied together, hobbles into our camp, presumably hoping to get at bit more hay. However, there is no more hay. It is meagre times, for men as well as for the camels, whose hump has been reduced to a pitiful little thing, hanging down their side. ”Camel caput,” says Dina. I guess it is not quite as bad, but if rain will not soon fall, their camels may very well perish.

Dina orders a 10-year-old boy, Ibrahim, to chase the camel back into the desert, but it assumes a threatening position, scaring the boy. The other boys laugh, pick up some branches and run towards the camel, yelling. This is too much for the camel, which immediately turns around, hobbling back into the desert.

At dusk, a white-eared bulbul (Pycnonotus leucotis) is calling from a dzal bush. Otherwise a complete silence prevails.