Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Zambia 1993: Hunting shoebill with camera

In several villages in and around these swamps, WWF has founded so-called Community Development Units. Each of these units co-operates with units in other villages, and with local authorities, to increase the standard of living of the local tribes. Simultaneously, WWF is trying to persuade the locals to harvest the natural resources in a sustainable way, so that these resources will also be available for future generations.

Together with Danish sociologist Peter Gregersen, who is working for WWF, I participate in a CDU meeting in the village of Kalasa Mukoso, near Samfya, which is inhabited by people of the Bena Kabende tribe.

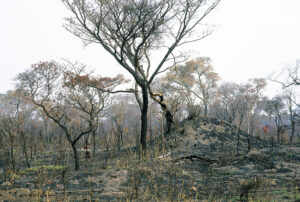

During the meeting, various local issues are discussed, including the burning of forest to create more farmland, how to protect crops against pests like bush pigs (Potamochaerus larvatus), and hunting bans on various game species, including antelope. I also participate in a merry meeting in the local Women’s Group, with much singing and dancing taking place.

One evening, we are seated in front of his house, talking. David confides in me that he is afraid of all wild animals, including lizards and frogs, and of course snakes. A couple of days ago he was a bit hysterical, when a frog was jumping about in his house, and I had to carry it out and release it some distance from the house.

Now I say, jokingly: “Maybe there’ll be a snake inside the house tomorrow!”

At this very moment, a thin, dark snake enters the veranda, just in front of David. He immediately jumps up and runs into the house, shouting: “Kill it! Kill it!”

However, I am more interested to find out, what kind of snake it is. As it turns out, it belongs to a group of completely harmless snakes, called shovel-snouts, genus Prosymna, which have a very flat snout. I manage to shoo it into a flowerbed, but David shouts excitedly: “It is hidden in there! Tomorrow, I’ll have these flowers removed!”

I am convinced that he is joking, but the following morning he persuades the watchman to remove the flowers.

Arriving at the opposite shore, we follow a narrow, twisting channel through high vegetation of papyrus (Cyperus papyrus) and reed (Phragmites australis). This channel is one of numerous tributaries to the great Luapula River.

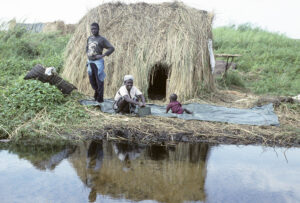

Along the shores of the channel are several temporary fishing camps, consisting of huts, built of reed and grass, allowing the wind to pass through the walls, which keeps the interior wonderfully cool. Many Unga families move to fishing camps for a period of three to four months each year, to catch and dry as many fish as possible. Later, the dried fish are sold at markets in villages on the mainland.

Finally, we arrive at Bwalya Mponda. Black clouds are looming on the horizon, but only a few drops of rain fall. Alex guides me to a house, owned by WWF, where I settle for the night. In the west, the sun disappears behind the clouds in a blaze of orange and red. After dark, a nightjar is calling, and numerous fireflies fly about, flashing.

Unga men have adopted the European dress. The women wear a European frock, and also a many-coloured chitenge, a piece of cloth, measuring about 2 x 1 m. Unga babies spend almost all their time wrapped in this cloth on the back of their mother (or sister, or grandmother), no matter what task she may be performing.

A group of women and girls are busy pounding tubers of cassava (Manihot esculentus), the staple food of the Unga. This is hard and tedious work. After several days of pounding, washing, and drying, the cassava flour is ready to be cooked to a porridge-like substance, called nshima. This porridge is eaten with fried fish and a bit of green leaves, sometimes wild plants from the swamps.

A woman is weaving a mat from split reed stems, tying them together with fiber strings. In the shallow water along the shore, another woman and some children attempt to catch small fish, using large baskets.

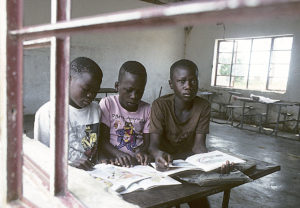

I pay a visit to the local school, which is in a very poor condition, and inside are very few tables and chairs for the children. Most Unga boys go to school for a longer or shorter period of time, but the girls must help their mother with her numerous tasks, so their education is often quite erratic. Unga people are of the opinion that education is not very important, as the children are just going to become fishermen or house wives. Education is also very expensive, and most Unga cannot afford to pay school fees. This is why the school building is not maintained.

The peculiar name of this bird stems from the shape of the bill, which is boat-shaped, with a hook on the upper mandible – it does indeed look like an old-fashioned wooden shoe. The Arabic name of this bird is Abu Markub (‘Father of the Shoe’). George and a local tracker are willing to guide me to a place, where it should be possible to see this enigmatic bird.

The following morning, we head out to walk 5 km to the southern end of Ncheta Island, where one of George’s uncles lives in a fishing camp. In this camp, we borrow a couple of canoes. A 12-year-old boy joins us to punt the canoe, in which I am a passenger, while George is punting the other canoe.

After some time, the water becomes very shallow, and finally we must give up punting, continuing our journey on foot. I am wearing an old pair of sneakers, whereas my companions are wading barefoot. Here and there, the bottom is very soft, and we often sink in mud up to our knees. It is very hot, but we can quench our thirst in small pools with crystal-clear water.

A grazing Zambezi sitatunga (Tragelaphus spekii ssp. selousi) immediately flees, sprinting across the swampy ground. This antelope is well adapted to a life in swampy areas, as its very long hooves are able to spread out widely, when the animal is running, preventing it from getting stuck in mud.

We also observe a pair of wattled cranes (Grus carunculata), a rare African species, which is declining everywhere because of draining of marshlands and construction of dams across rivers. The total population may be less than 10,000 individuals. In the Bangweulu Swamps, however, it is still fairly common.

We now commence our return journey. How my companions are able to find their way in this featureless landscape is a mystery to me, but we arrive at the exact same spot, where we left our canoes.

Back at the fishing camp, we are served nshima, fried fish, and a few vegetables for lunch.