Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Tibet 1987: Tibetan summer

This word conjures up pictures of wind-blown mountain passes with stone cairns, adorned with hundreds of fluttering Buddhist prayer flags; of Tibetan wild asses (Equus kiang), grazing on a meadow among countless red primroses and yellow louseworts; or perhaps of Swedish explorer Sven Hedin (1865-1952), who was the first European to explore the area around the sacred Mount Kailas in western Tibet – the physical manifestation of the mythical mountain Meru and an important pilgrimage destination for followers of three religions: Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism.

Transhimalaya (which literally means ’on the other side of the Himalaya’) consists of two mountain ranges, Gangdise and Nyenchen Tanglha, stretching altogether c. 1,600 km across the southernmost part of the Tibetan Plateau, parallel to the Himalaya. In daily speech, though, the word includes the entire plateau.

For hundreds of years, Tibet was forbidden area for Western travellers. A harsh land with extreme climatic conditions, situated at an altitude between 3,000 and 6,000 m. Summers are usually hot, with a glaring and fierce sun – but an occasional snowstorm is not uncommon. Winters are severe, with temperatures often below -30o Centigrade.

An environment like this creates tough people – and Tibetans are tough. Many are nomads, herding huge flocks of goats, sheep, and yak. They live in black tents, made of felt. Others are farmers, growing barley, buckwheat, and vegetables in river valleys. Naturally, these people live in close contact with nature and natural forces.

The following morning, we learn that the road between the border and the first Tibetan town, Khasa (or Zhangmu, as the Chinese prefer to call it), has been washed away, and the bus service has been cancelled. We shall have to take a 9-km-long shortcut on foot through the forest.

In Kodari, a number of guides are willing to show us the way through the forest, and to hire porters to carry our luggage. We pass the ‘Friendship Bridge’ across the Bhote Khosi River, which constitutes the border, and begin our ascent. The faint trail through the forest is very slippery, and as it is still raining, we must walk with care to avoid causing new landslides. During the walk, we have a pleasant conversation with our guide, who is a friendly man. A crested serpent-eagle (Spilornis cheela) is soaring over the forest, screaming.

Early in the afternoon, we reach the customs office, just below Khasa. The staff here shows no interest whatsoever in our luggage, and we pass through customs without problems.

Following the introduction of tourism in China, the Yuan has two values. Everyday money is RMB (Renminbi), called ‘people’s money’. Tourists cannot buy RMB in the bank, but must buy FEC (Foreign Exchange Certificates), called ‘tourist money’, which is 50% more expensive than RMB. In this way, the Chinese get more money out of the tourists, as the two currencies have equal value in the trade.

The only advantage for the tourist is that using FEC he or she can buy ‘luxury goods’ in the so-called ‘foreign shops’, where RMB are not accepted. Therefore, these goods are out of reach for the common citizens in the Chinese territories, paving the way for a most profitable black market: sometimes you can get twice the value of FEC in RMB. Naturally, this is highly illegal, but nobody seems to care.

[In the early 1990s, the dual currency system was abolished, and FEC was removed from the market.]

An important issue of Lamaism is to preach that all things are connected. Man’s energy is a part of the energy of the Universe, and to increase your knowledge about these energies, thereby changing your mental level, you can meditate, or you can recite powerful words, mantras. The ultimate goal is to liberate your soul from the eternal series of re-incarnations. This goal is called nirvana.

Only the selected few are able to obtain nirvana, while the vast majority must be reborn again and again. The shape, in which this takes place, depends on the number of good or bad deeds you have done in your lifetime. If you have done many bad deeds, you may be reborn as an animal, so it is quite natural that killing is a great sin to devout Tibetans.

The highest monks are called lamas, and most of their time is spent helping other people to practise a more efficient form of meditation. This takes place in monasteries, and over the years, thousands of such structures were erected throughout Tibet. Most families would send a son to a monastery to be enrolled as a monk, but this was in no way compulsory. At any time, a monk could choose to leave the monastery to return to his former life as a nomad or a peasant.

Over time, various branches of Lamaism evolved, often with rather subtle differences. The most well-known is Gelug-pa, ‘Yellow Hats’, named after their yellow headgear. Their highest lama is the Dalai Lama, meaning ‘Ocean of Wisdom’ in Mongolian. He is an incarnation of the eleven-headed Chenrezig (‘Buddha of Compassion’), which is again one of Buddha Sakyamuni’s incarnations. The Dalai Lama is also the secular leader of all Tibetans and Mongolians.

The present 14th Dalai Lama was born in Kham, eastern Tibet, in 1935, named Lhamo Döndrup. In 1939, he was brought to the capital, Lhasa, where his was to reside in the Potala Palace (‘The Palace of a Thousand Rooms’). From that day, he was called Tenzing Gyatso, Gyatso being the Tibetan word for the Dalai Lama.

You may read more about Lamaism and other branches of Buddhism on the page Religion: Buddhism.

Chairman Mao and the other communist leaders had informed their troops that the Tibetans had to be liberated from their life as slaves under a theocratic rule, which had gathered immense wealth, whereas the common people were living in poverty. These theocrats were influenced by imperialist Americans and Brits, who, in fact, had the real power in the country, the leaders told the soldiers. At this time, however, only six westerners were living in Lhasa, including two Austrians, Heinrich Harrer and Peter Aufschnaiter, who had fled to Tibet in 1943 from a British prisoner’s camp in India. Harrer later wrote a book, Seven Years in Tibet, about their adventures.

The Chinese, who had expected to be received as liberators, were much surprised to encounter a stubborn resistance from the Tibetans. They were not aware that the theocrats were very popular among the population. The Dalai Lama was only fifteen years old, but was already a favourite with the people.

Following the invasion, the Dalai Lama had a very difficult time negotiating the degree of self-government in Tibet. Conditions slowly got worse, and in 1959 the Dalai Lama, accompanied by several Tibetan nobles, fled to India, as rumours had it that the Chinese were planning to murder him.

When, in 1966, Mao Zedong instigated the so-called ‘Cultural Revolution’, a mass destruction of cultural treasures began, not only in Tibet, but in all Chinese territories. Religious paintings were destroyed, icons were smashed, and monasteries were torn down by gangs of ravaging Red Guards. Violence and killings flourished as never before. Most of Tibet’s production of crops was carried off to China, resulting in the starvation of many Tibetans. One estimate says that about 1.2 million Tibetans died as a result of the Chinese occupation. – Further atrocities during the Cultural Revolution are related in depth on the page Folly of Man.

After the death of Chairman Mao in 1976, followed by the arrest of the so-called ‘Gang of Four’, conditions changed. The Cultural Revolution came to a halt, and the restrictions on religious practice were somewhat eased. Jokhang, the largest religious sanctuary in Lhasa, which during the Cultural Revolution had functioned as a pig-pen, was re-opened. In many other monasteries, monks were allowed to carry out their duties, and Lamaism again began to flourish. Large groups of Tibetan pilgrims streamed to the monasteries and temples.

In the 1980s, the advantages of tourism dawned to the Chinese, as it would bring foreign currency into China, thus allowing the elite to acquire foreign luxury goods. Prior to the 1980s, it was almost impossible to get permission to travel in Tibet, but from 1982 Lhasa could be visited by groups, and by 1984 individual travel was allowed.

Tourists now poured into the country – finally the Promised Land was open to travel. Everything you had been reading about and dreamed to see was suddenly within reach. A large-scale restoration of temples began, but many cultural treasures were lost forever.

We, a small group of westerners, negotiate the price with the owner of a minibus, who is willing to take us to Lhasa for 200 Yuan (c. 50 US$) per person, provided there are at least six travellers. All six of us are not going any further than Shigatse, but this has no effect on the price. The free market forces have arrived in China! We return to our hotel to fetch our luggage.

Initially, our journey brings us through lush hardwood forest with many waterfalls, but soon the road becomes very steep, the broad-leaved trees giving way to conifers. Further up, the trees disappear, and the main vegetation is now scattered shrubs and prickly Tibetan globe-thistles (Echinops cornigerus).

In the meadows, however, an abundance of flowers are in bloom, including the white-flowered riverside windflower (Anemone rivularis) and the tall, yellow-flowered Sikkim primrose (Primula sikkimensis).

Eventually, also the shrubs disappear, and the landscape becomes barren and dry. We are now on the Tibetan Plateau. The sky is overcast, but only a few drops fall.

The bus makes a stop in Nyalam, a small and rather ugly town – merely a truck stop with a number of hotels and restaurants. In what rather resembles army staff quarters, but turns out to be a restaurant, we have a meal of rice and fried vegetables, served with green jasmine tea.

A lot of Chinese are busy eating, and their eating habits are definitely worth a study. Using their chopsticks, they shovel rice into their mouth, not the least concerned that some of it is spilled on the table or on the floor. Smacking their lips and burping, they throw gnawed chicken bones over their shoulder. When a group has left, their table and its surroundings resemble a battlefield.

Towards the south, splendid Himalayan mountains soar towards the sky, including Gauri Shankar (7145 m) and Shishapangma (8013 m), the latter called Gosainthan in Nepal. In Hinduism, Gauri-Shankar conveys the unification of the gods Shiva (also called Shankar) and his female aspect Devi (also known as Gauri) – a symbol of fertility. Gosain is also another name of Shiva. – You may read in depth about Hindu gods on the page Religion: Hinduism.

At an altitude of 5,000 m, we make a brief stop at a pass, marked by a number of stone cairns. Poles have been placed among the stones, and on ropes, tied between these poles, numerous colourful prayer flags are fluttering fiercely in the strong wind. On these prayer flags are printed Buddhist mantras, which are transmitted into the Universe by the wind.

The mountains along the road come in all shades of colours: brown, grey, greenish, red, violet often with a touch of blue, yellow, or orange from the sparse vegetation. Some of the rock layers are twisted and folded – proof that they were once the bottom of a huge sea, the Tethys Sea, which, aeons ago, covered this area. About 60 million years ago, the continental plate with the landmass that is today the Indian Subcontinent, drifted north to collide with the Asiatic continental plate, uplifting the hardened sediments on the sea bottom to form the Himalaya and surrounding mountain ranges.

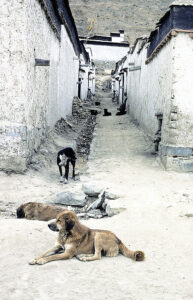

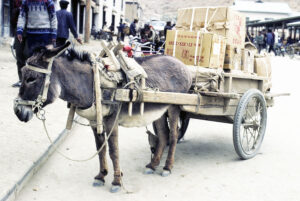

Occasionally, our bus passes through a small village, built beneath a mountain or along a river. The houses are dirt-coloured, blending very well with their surroundings. People travel in carts, drawn by horses or donkeys. Tree sparrows (Passer montanus) twitter among the houses, and ravens (Corvus corax) soar, screaming hoarsely. The river valleys are covered in dense vegetation of grass and shrubs, where thousands of sheep and many yak are grazing. Late in the afternoon, the landscape is bathed in a gorgeous yellowish light from the setting sun.

The hamlet of Tingri, also called Xegar, is a truck stop, situated at an altitude of more than 4,000 m. The local restaurant is not a very cosy place, looking more like a stable than a place to eat. Small groups of freezing tourists huddle around the tables. No food is served at this time, but our friendly German fellow travellers share their instant soup with us.

Not that I have any appetite. A splitting headache, nausea, and a galloping pulse are sure symptoms of AMS (Acute Mountain Sickness), a condition caused by lack of oxygen in your body. Today, we have ascended from 1,800 to over 4,000 m altitude, and the air here contains only about two thirds of the amount of oxygen as at sea level. The best cure is to descend, but this is not possible at present.

As if AMS was not enough, I also get diarrhoea. I almost crawl to the tiny toilet building, which has low walls and no roof. This means that during your business you can admire an incredibly starry sky. However, I am not able to appreciate stars or anything else. I swallow a couple of painkillers and creep into my sleeping bag. Throughout the night, I am extremely uncomfortable, my heart pounding. The night seems endless, as I am disturbed by other tourists, who discuss similar symptoms, and by speeding trucks.

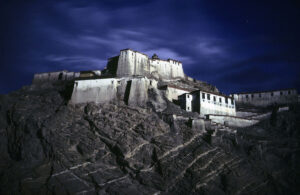

Our bus now heads east, bringing us through villages and along rows of poplar trees, bordering green fields of wheat. Our goal is the town of Shigatse, where we check into at a small hotel, with a splendid view towards the remains of a huge fort, Samdup-tse Dzong, which was formerly the seat of the local government. It was almost completely destroyed by Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution. On the fort wall, Chinese authorities have placed gigantic loudspeakers, every day blaring propaganda, harassing people. The central part of Shigatse has been bulldozed and replaced by broad streets and concrete houses with very little appeal.

At the market, a variety of interesting items are for sale, including rancid butter, packed in goat skin bags; entire dried goats, stiffened in grotesque positions; jewellery, consisting of large pieces of turquoise and coral; traditional medicine, made from herbs, pulverized horns of hornbills, dried lizards, musk from the belly gland of the musk deer (Moschus), and many other ingredients. We also observe three pelts of lynx (Lynx lynx) and two of leopard (Panthera pardus). In fact, it is illegal to sell pelts of wild cats in China, as they are protected by law, but nobody seems to care.

An elderly man is standing in the doorway of his house. When I ask permission to take his photograph, he cracks down laughing and invites us in. In the courtyard, which is full of cows, chewing the cud, a young woman is suckling her baby, whereas the man’s wife stares at us, astonished to see us here. She is clearly uncomfortable because of our presence, as Tibetans are not supposed to mingle with ‘imperialist’ foreigners.

Her husband just laughs, and inside the house we are served several glasses of chang (beer, made from fermented barley), with a little tsampa (roasted barley flour) in it. A corner of the living room is occupied by a large bench, adorned with painted dragons, and a huge prayer wheel, which is turned by the heat from a lighted candle. Inside these prayer wheels are scrolls with written mantras, which are transmitted into the Universe by the turning wheel. Before we leave, the man asks us for a photograph of the Dalai Lama, and, naturally, we hand him one.

For many years, the Tibetans regarded the 10th Panchen Lama, Gonpo Tseten, as a renegade, who co-operated with the Chinese authorities. In 1982, after 19 years of house arrest in Beijing, he was finally allowed to visit Lhasa.

During a public speech in Jokhang, the most sacred of all Tibetan temples, he said: “There is only one human being worthy of occupying this throne: His Holiness the Dalai Lama.”

Uttering these words, he once again rose to honour and dignity among the Tibetans, and in his hometown Shigatse, thousands of people gathered to pay tribute to him. The Chinese authorities, however, were furious, and the Panchen Lama was severely punished for his ‘reactionary’ speech.

Every room houses numerous statues, of Buddha Sakyamuni, of various bodhisattvas (monks that refrain from entering nirvana, instead choosing to guide other people towards the goal), of demons and guardians. In front of the Buddha statues, hundreds of yak butter lamps are burning, emitting a distinct smell of rancid butter.

Monks, clad in red robes, are chanting, some beating large drums or cymbals, others blowing into large conches. The walls are decorated with paintings and tankas (large scrolls, made from cloth), depicting Buddhist issues.

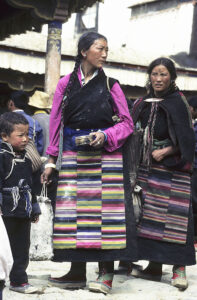

We follow a group of friendly pilgrims around the complex. Many have come from far away, travelling for days to reach Tashilhunpo. They are clad in thick woollen clothes and wear felt shoes, made from goat hair. The married women wear a thick apron around their waist, made from three pieces of woven cloth, sown together lengthwise, one above the other. In front of each Buddha statue, the pilgrims make small offerings of barley, tsampa, or money.

Before visiting the sanctum sanctorum, merit is gained by circumambulating the entire temple complex along a route, called kora, which is several kilometres long. Some pilgrims prostrate all the way, lying down and stretching their arms in front of them, as far as they can reach. On this spot, they place their rosary, after which they get up, walking the few steps to the rosary, and prostrate again, repeating this procedure countless times. Devout pilgrims travel in this way from their home village to a temple, often being on the road for years. During their pilgrimage, other pilgrims, or resident farmers, will feed them.

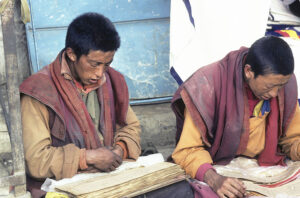

From a courtyard, we hear voices and clapping sounds. A group of monks are performing a lesson of ‘intellectual discussion’. Two by two, the monks are facing each other. One monk gives a speech, emphasizing his words by slapping one hand into the palm of the other hand, while his opponent makes comments, whenever he feels like it.

As many tourists over the last few years have been unable to show proper conduct during this ritual, the Chinese authorities have decided that tourists can no longer participate in sky burials. They are allowed to watch them, but only from a distance. Consequently, we take our seats in the grass on a nearby hill and wait. Clouds come and go, creating ever changing patterns of light and dark on the mountain slopes.

Finally, a tractor arrives with two bundles, which men proceed to carry twice around a large circle, where several fires are burning. The bundles are then placed on a nearby slanting rock, which is darkened by dried blood, whereupon the men take their seat inside the circle. A few minutes later, they get up, pick up some bowls of tsampa, and walk up the slope to the bundles. Facing the mountains, they throw some of the tsampa into the air, shouting, the sound reverberating between the hills. From the rocks, about fifty Himalayan griffon vultures (Gyps himalayensis) take off, soaring over the area.

The two men now begin to cut up the bodies. Arms and legs are dismembered, and the meat is cut into long strips, which is again divided into smaller strips. In this way, most of the body is divided into small pieces, the skull and the rib case being left intact. The men then return to the circle.

The vultures drop from the sky, gorging on the meat, while ravens and Himalayan black kites (Milvus lineatus) make an effort to get a share. Occasionally, two birds fight over some tidbit, their heavy wing beats causing a cloud of dust to rise. When their stomach is full, they hop clumsily up the slope, where they begin digesting their meal.

A couple of Japanese tourists, who have approached too close, are chased away by the butchers, who shout angrily at them. They then return to the bodies, armed with large hammers to crush the bones, whereas the skulls are crushed by dropping a large stone on them. This is lengthy work, as the bone splinters must be very small, before the birds are able to swallow them. The broken bones and the brain are mixed with tsampa, which is strewn on the slope. Some of the vultures, which haven’t had their fill, return to the spot, and soon all that remains of the deceased is a couple of splintered bones and a little dried blood.

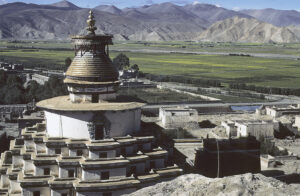

The town is tiny and very peaceful. Two rows of houses and shops line the main road, leading up to the huge Palcho Monastery, enclosed by a long wall. On the temple premises is a large, pagoda-like structure, kumbum (which means something like ‘one hundred thousand holy images’) – a three-dimensional mandala, depicting the Buddhist cosmos.

In the main building of the monastery, the frescos on the walls have been restored, but in a smaller building behind the monastery we witness several examples of the destruction that was carried out by Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution. Using hammer and chisel, the faces of the depicted Buddhas and bodhisattvas were chipped away, and several rooms have been completely destroyed.

Outside the gate, an old woman hands us a tattered note, informing us that there is an entry fee of 2 Yuan (50 US Cents) per person. An elderly man, clad in red and wearing a large, brown felt hat, gives a long talk, of which we understand absolutely nothing.

A jeep now arrives with three Chinese and a few Tibetan tourists. We obtain tickets, whereupon the guide opens the large, squeaking gate. He talks Tibetan and a bit of English, but is somewhat reserved during our tour around the fort. He doesn’t mention anything about the destruction, which took place during the Cultural Revolution, no doubt because of the Chinese tourists.

When the tour has come to an end and the other tourists have left, the old man suddenly becomes much more informative. He gives a colourful description of the bombardment by the British troops, and the ravages, caused by Red Guards. The monastery inside the fort has many rooms, and the destruction of cultural treasures is obvious. One of the rooms once contained fine frescos, depicting the eleven-headed and thousand-armed Chenrezig, of whom the Dalai Lama is an incarnation. There also used to be three gilded bronze statues, but they were stolen, and the present ones are poorly crafted copies.

From the top of the fort, we have a splendid view over the valley, where women are on their way home through the fields, hoes slung on their shoulder. Beneath the rock lies the town, with its huge monastery and the kumbum. The guide points out several other monasteries, which were destroyed by the Red Guards.

This looks indeed inviting, and we decide to stay here a few days. However, there are no hotels in the village of Nagarze, but following some difficult negotiations, as our Chinese vocabulary is very limited, we are allowed to spend the night at a small army camp, in which there is a spare room. The rest of the day we relax to avoid getting acute mountain sickness, as the altitude is around 4,600 m. In the evening, a lot of children from the village visit us. The event of the day for them is being allowed to use my binoculars.

The lake side is lovely. Yellow long-tubed louseworts (Pedicularis longiflora var. tubiformis), red primroses (Primula), and yellow saxifrage (Saxifraga) grow in the meadows, where Tibetan larks (Melanocorypha maxima) and Tibetan snowfinches (Montifringilla adamsi) hop about.

Here and there are small dens, from which black-lipped pikas, or mouse-hares (Ochotona curzoniae), peep out. About 12 species of these small, rodent-like animals live in Central and East Asia, besides a few species in Siberia and North America. They may look like rodents, but are in fact related to rabbits and hares. During the summer months, they collect large amounts of grass and other plants to store as winter food, as they do not hibernate.

There is an abundance of birds in the lake. A goosander (Mergus merganser) is swimming with her five ducklings along the shore, where redshanks (Tringa totanus) and mongolian plovers (Charadrius mongolicus) are scolding. On the lake surface, large flocks of brown-headed gulls (Chroicocephalus brunnicephalus) and Pallas’ gulls (Ichthyaetus ichthyaetus) are resting.

The soldiers cannot (or, rather, will not) tell us what has happened, but one of them offers to join us to the police station in Nagarze to make a report. The officer in charge is not at all interested, but instructs us to go to the police station in Lhasa. The soldiers agree to give us a letter, which we have to bring to the police in Lhasa, after which we must return to Nagarze with an officer, but, for some reason or other, they demand that one of us stay in the army camp. This is out of the question, so we decide to go to Lhasa to make a police report there.

Part of the way, the road follows the shore of a great salt lake, Yamdrok Tso, which appears far more barren than the lake at Nagarze. The bus huffs and puffs up a steep gravel road towards a pass, only to zoom down through several hairpin bends at a tremendous speed.

Finally, we reach a surfaced road, and the last 100 km before Lhasa are fairly easy going. From a distance, we can now see a huge palace, looming over the town. This is Potala, former winter residence of the Dalai Lama, today a museum.

“The staff is having lunch. Come back at 4 p.m.”

At 4 p.m., I get this message: “The officer, who is going to take care of your case, is at a meeting. Come back on Monday.”

Sunday morning, we pay a visit to the impressive Jokhang Temple, the most important shrine in Tibet. In front of the entrance, two huge clay ovens emit a balsamic fragrance of burning juniper branches. The roof of the temple is dominated by a large golden Dharma Wheel, whose eight spokes symbolize the eight-fold path to nirvana. The wheel is flanked by two deer, symbolizing the deer park in Sarnath, near Varanasi, where the Buddha gave his first lecture after finding the way. – You may read more about the Dharma Wheel and other aspects of Buddhism on the page Religion: Buddhism.

Numerous pilgrims are gathered in front of the entrance. They are standing with their hands cupped, whereupon they kneel and finally prostrate, their hands stretched out in front of them. Hundreds of times they repeat this ritual, muttering their most important mantra: “Om! Mani padme! Hum!” (“Om! Jewel in the Lotus Flower! Hum!”) Om and Hum are powerful mantra words, the jewel is the Buddha, and the lotus flower symbolises purity.

Some pilgrims have tied flip-flop sandals to their hands, to protect their skin from being scraped off on the rough slates. Others have brought mats to protect their knees. Through the centuries, most of the slates have been worn smooth by the hands and knees of thousands of pilgrims.

Inside, the temple is adorned with dozens of beautiful frescos and hundreds of Buddha statues, in front of which countless yak butter lamps are burning. Numerous pilgrims walk along rows of prayer wheels, rotating them with their right hand. Outside the building, monks are bent low over books, studying sacred texts.

A happy and positive atmosphere prevails here.

“There is no theft in China!” he says.

“I beg your pardon? Well, anyway, I have lost my camera and some film rolls!”

“First you tell me that your camera has been stolen, then you say that you have lost it. We cannot make a report, when you cannot give us a clear account of what happened!”

Astonished, I ask: “You are not going to make a report?”

“No!” he answers, turning his back to me and ignoring me completely. Bubbling with rage, I leave the building.

Quite depressed, Jette and I stroll down the streets of Lhasa. Passing a camera shop, we notice some Kodak film rolls, displayed in the window.

“They are probably your film rolls!” says Jette jokingly.

We enter the shop to enquire about the price. As it turns out, they are quite cheap, so I ask for more. The sales clerk leaves, returning a little later with more film rolls, wrapped in plastic, which I immediately recognize. They are my film rolls! With mixed feelings, I buy enough for the rest of our stay in Tibet and China.