Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

India 1986: “Sir, would you like to see this peacock?”

The slow pace of the train gives us ample time to enjoy the landscape, which is far from dull, alternating between yellow sand dunes, red sandstone outcrops, and flat sand or gravel plains with scattered bushes and trees, including a cactus-like species of spurge, Euphorbia caduca, locally called thor, Sodom apple (Calotropis procera), called akaro, and a small tree, Salvadora procera, called dzal. Here and there, small herds of Gujarat gazelle (Gazella bennettii ssp. christii) and nilgai antelope (Boselaphus tragocamelus) are grazing on the sparse vegetation.

The fruit of Sodom apple was first described by Roman historian Titus Flavius Josephus, born Yosef ben Matityahu (c. 37-100 A.D.), who found it growing near the city of Sodom: “which fruits have a color as if they were fit to be eaten, but if you pluck them with your hands, they dissolve into smoke and ashes.” (Source: W. Whiston 1737. The War of the Jews, Book IV, Chapter 8)

Titus is referring to the fact that the ripe fruit easily dissolves, releasing hundreds of downy seeds, which are scattered to the four winds.

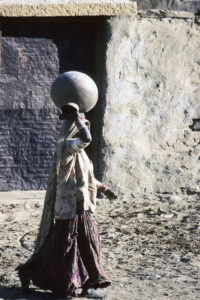

Occasionally, the train passes small clusters of brown or white houses. Women, clad in brightly colored saris, walk gracefully from the village well to their home, with brass jars balancing on their head. Men ride camels with a dignified air, striding across the sand in what appears to be a slow motion, but is in fact surprisingly fast.

Fields are hibernating throughout the dry winter and spring. On one field, thousands of chili peppers are drying in the sun, their bright crimson colour contrasting with the brownish-yellow desert sand.

This gigantic yellow sandstone structure looms over the town, telling a tale of war and rivalry in the desert. Founded around 1155 by a Rajput prince, Roa Rawal Jaisal, it was originally surrounded by an outer wall, 4.5 km long.

From the walls of the fort proper, we have a marvellous view over the town. In the old days, the walls were fortified by 99 ramparts, constructed to defend the king and his people. From these ramparts, soldiers would roll large stone balls and long stone cylinders over the edge, crushing many enemies, who were trying to scale the walls of the fort. Still today, many of these balls remain on the walls.

Early in the 18th Century, people began building houses within the outer fort walls, and today most of the town is situated here. Inside the fort proper, most of the area is also occupied by residential houses.

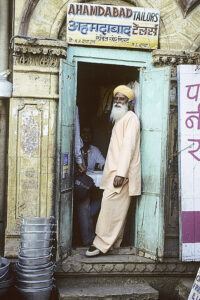

Many mansions in Jaisalmer, called havelis, are built from blocks of yellow sandstone, carved into the most intricate patterns. On more humble dwellings, paintings of Ganesh, Krishna, and other Hindu gods often adorn the walls. – Hindu gods are described in depth on the page Religion: Hinduism.

The doors are often painted in bright colours, and above many of them is placed a brass bird, on which is written Welcome.

The carcass of a dog beneath the fort is surrounded by more than a hundred white-backed vultures (Gyps bengalensis). When a dominant bird arrives, it will lift one foot slowly towards the vulture, which is presently eating. If this bird does not instantly retreat, there will be a fight. The birds try to grab their opponent with their talons, pecking at each other and beating their great wings, dust flying all over.

We leave an hour before dawn. It is quite cold, and when we arrive at Sam, the driver and his son light a small fire to keep warm. After enjoying the sunrise over the dunes, we instruct our driver to go to the national park. However, he turns the car, heading towards Jaisalmer.

“No-no,” I say. “We are going that way, into the desert!”

He looks at me, somewhat bewildered, then steers the jeep along the track towards the desert. After a few hundred yards, however, the vehicle slows down and then comes to a complete stop.

“What’s wrong?”

“No desert jeep!” he says.

“No desert jeep? But we rented the jeep to go into the desert!”

The man hasn’t got a clue, what I am talking about, but stares desperately at me.

“No desert jeep!” he says again.

I confer for a moment with my companions, and we decide to give up. Sulking, we head towards Jaisalmer. Not even a couple of beautiful gazelles in the fine morning light can cheer us up. Back at the hotel we complain to the receptionist, who informs us that there was not enough petrol to go into the desert. When we point out that our agreement included a desert trip, he says: “Oh, you wanted to go into the desert? No problem, Sir, I’ll join you there myself right away!”

The day is still young, so maybe the trip can be made after all. The receptionist brings along a couple of friends, causing the front seat to be quite crowded. However, they are all laughing, while Indian pop music is blaring from their cassette player. Not exactly our taste, but hopefully they’ll soon switch it off.

Instead, we make a stop to stroll among marvellous red sandstone outcrops, on which agamas scuttle up and down. Large black beetles run across the sand, leaving tiny lines of tracks. Around us, desert larks (Ammomanes deserti) twitter, and variable wheatears (Oenanthe picata) cock their tail, flashing white. Above us, two laggar falcons (Falco jugger) are soaring. We take our seat on a couple of flat rocks to enjoy the peace and quiet.

However, suddenly the silence is shattered. The boys have turned up the volume of the cassette player, causing Indian love duets to blast through the air. We get up and descend towards the car, rather angry. Tersely, we explain the boys that we haven’t gone into the desert to listen to music, but to enjoy the peace and to watch birds. Birds! Do you understand?

“Yes, Sir, we understand,” they declare, cutting off the tenor in the middle of his ballad to the slim maiden.

Now we commence our journey in absolute silence – the boys dare not speak a word. But suddenly the receptionist turns his head, saying, “Sir, would you like to see this peacock?”

Right in front of the car, a great Indian bustard is crossing the road! The boys now witness a complete change taking place in the strange Europeans on the back seat, who start shouting, pointing their telephoto lenses out of the window. Their bad mood is gone, and they laugh!

The boys regain their speech, and we happily zoom across the desert on soft sandy tracks. The wheels whirl up huge clouds of dust, and to prevent being suffocated we must cover the window frames with canvas tarpaulins, as they have no glass panes. This blocks our view, and from our positions on the back seat we’re not able to see much.

The car suddenly slows down, and even though the driver steps hard on the gas pedal, the car comes to a complete stop, stuck in the soft sand. On a prior trip across Africa, I have often experienced similar situations, so it won’t be a problem.

“Where are your shovels?” I ask.

“Shovels?” The boys look puzzled. “We don’t have any shovels!”

So, we shall have to use our hands. While the boys scrape away sand from the wheels, we break off branches from bushes and place them under the wheels. After a few failures, we succeed. No need to get mad again!

“I can also arrange a genuine Rajasthani meal for you there,” he says.

“We would like that, but it must be a simple meal – and not too expensive.”

We don’t want to be tricked once more, but he guarantees that the meal will be simple.

We must admit that Khudi is a beautiful place, and while we sip tea in a tea shop, the receptionist leaves to arrange for our meal. Time goes by – still no food. We ask him, if the food will soon be ready. Yes-yes, it won’t take long. Hours pass, and we lose our patience.

“If the food is not ready in half an hour, we shall cancel the whole thing!”

“Yes, Sir, it will be ready!”

A little more than half an hour later, they bring us to a house, and we enter. Holy mackerel! The mats on the floor are absolutely packed with innumerable trays of food: chapatis and paratas (two types of pancake-shaped loaves), curry dishes with every kind of vegetable available, lentils, eggs, and many other items. It looks inviting, indeed, but what on Earth will it cost? For a moment, we are paralyzed. Then we call the receptionist.

“What is the meaning of all this?”

The young man explains that the owner of the tea house has demanded a ‘special’ lunch for us, because our four other companions have eaten in his tea house and paid only five Rupees each. This is his way of getting the rest of the money.

“What is the price of this meal?”

“Only a hundred Rupees!”

“A hundred Rupees! That’s not cheap! A cheap meal for three people costs 30 Rupees! We didn’t order all this food, and we don’t want to pay a hundred Rupees!”

“Yes, Sir, you can pay whatever you like!”

We have been tricked again. The nice lady, who spent hours cooking all this food, is not going to be cheated, because the landlord of the tea house was tricked by the boys. Therefore, we take our seat on the mats and start eating. It is absolutely delicious!

We pay the woman a hundred Rupees and thank her for our gorgeous meal.

In the evening, we call the receptionist to pay for our trip. We check his bill very carefully, noticing that he has charged extra money for the morning trip to Sam. The number of miles driven the rest of the day is also slightly inaccurate – in favour of the receptionist, naturally. We inform him of these facts, and that we intend to subtract a hundred Rupees from the bill.

“That’s quite all right, Sir.”

“We are also going to subtract 40 Rupees, because your four companions had their meal at our expense!”

He explains that the young man in Khudi tricked him to order all that food. We don’t know what to think, but agree to subtract only 25 Rupees. We ask him to get the rest of the money from the young Khudi resident’s relatives in Jaisalmer.

“That’s quite all right, Sir. No problem!”

We must admit that he takes it all very well and is not at all angry. If the Europeans would pay for his little joke, that’s fine. If not, that’s also fine. When we leave a few days later, we are still on friendly terms, and his good-bye is hearty.