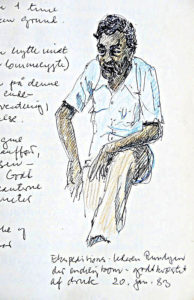

Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Sri Lanka 1983: Jungle trip with Ranjan

An elderly Tamil woman is selling paan, a mild intoxicant, which consists of a leaf from the betel bush (Piper betle), wrapped around the following ingredients: bits of a nut from the betel palm (Areca katechu), lime, a paste (katha), made from the wood of Senegalia catechu (an acacia), and, according to your taste, tobacco or spices.

A couple of young men approach us to talk. When they learn about our plans to visit the remote nature reserve Wasgomuwa, they explain that it is very difficult, if not impossible, to visit the reserve proper, but they know an area with pristine jungle near the reserve, where it should be possible to see elephant (Elephas maximus), sloth bear (Melursus ursinus), leopard (Panthera pardus), and many other animals.

The brothers inform us that where we are going you cannot buy anything, so we give them 1,000 Rupees, to buy supplies for the trip. Ranjan will pick us up at our hotel at 6 A.M. two days later, as the bus heading north will leave at 6:30.

At six o’clock on the appointed day we are ready to go. No Ranjan. At 6:30, still no Ranjan. We are now beginning to get nervous that the brothers have cheated us and run away with our money, but as our hotel owner knows them, this is not likely.

Finally, both of them arrive in a taxi. They look as if someone has beaten them up, and they stink of arak, a local type of alcohol. Obviously, they have been on the bat all night long. Well, it’s Ranjan’s salary they have squandered, so that’s their own business.

Jumping into the taxi, we drive to the bus station to await the next departure north, an hour later. Ranjan is leaning against a pole, shaking all over and looking really awful.

In Mahiyangana, we learn that no buses will be leaving for our destination due to damaged roads. Instead we manage to get a lift on a truck. The road is in a terrible condition, with deep pot-holes and muddy stretches. Foolishly, our driver moves his vehicle into a rather deep mudhole at a snail’s pace, so naturally we’re stuck. The driver speeds up frantically – but to no avail. A wire is tied to a passing tractor, but soon both truck and tractor are stuck. The tractor, however, manages to get out, this time hauling the truck out backwards. Now the truck can pass through the mudhole at a more efficient speed, but when we encounter several similar holes, the driver decides to turn back.

As we are now without transportation, we shall have to walk the last 3 km. Ranjan is carrying the box with provisions on his head, sweating profusely. By now he has become fairly sober. Along the road, peasants are ploughing paddy fields with the help of water buffaloes – hard work in the sticky mud.

On our way, we make a brief stop at a house, which belongs to Ranjan’s friend. We are received by his sons, but he himself is out in his chena, a clearing in the jungle, to guard his crops against elephants and wild boar (Sus scrofa).

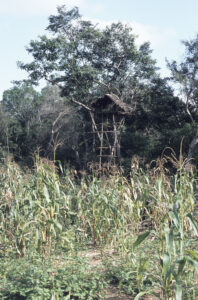

Now it seems that the driver wants to show us his skills at manoeuvring the big machine, zooming along full speed on the muddy road. When we finally arrive at our destination, all of us are more or less covered in mud stains from the wheels. The whole merry crowd joins us through the jungle to the chena, where maize plants, 2 m tall, are swaying in the slight breeze, with small patches of pumpkins and beans here and there.

Ranjan’s friend and his wife live in a small, simple hut. Naturally, they are much surprized to see us out here, but, nevertheless, receive us very courteously.

We have a welcome bath in a nearby stream, after which we are guided to a tree at the edge of the maize field. In this tree, a covered platform has been constructed, and this is to be our home for the next four nights.

So, this is the ‘treetop hut in the jungle’, as our alcoholic friend expressed himself back in Badulla. Well, we cannot deny that it is situated near the jungle.

As we are busy trying to identify some birds, we are suddenly frightened by a gunshot – our tracker has aimed at a tufted langur monkey (Semnopithecus priam ssp. thersites), luckily without hitting it. We scold him, but he looks utterly puzzled.

As it turns out, until now Ranjan has not taken the trouble to inform him why we have come here, but he readily agrees only to shoot, when we are in danger. We then proceed along the path, but observe noting but tracks of a wild boar. Dusk is approaching, so we must return to the chena.

Ranjan disappears, his excuse being that he wants to change the cartridges he bought in Badulla to a larger calibre – suppose we meet buffaloes, he says. Later in the evening he returns, so drunk that we abstain from attempting to communicate with him this evening.

The tracker’s wife is a sweet person, who takes very good care of us. She speaks a little English, so we can communicate with her without Ranjan. The little food she and her husband have is shared with us, and she apologizes that the meal is very simple. On the contrary, it is delicious!

By now, we are rather tired and retire for the night to the platform, where we creep into our sleeping bags. We must admit that it’s quite cosy here!

In the dark, we hear a calling Jerdon’s nightjar (Caprimulgus atripennis) and a hooting collared scops owl (Otus bakkamoena). For some time, we are kept awake by shouting people, who try to shoo away wild boar and feral water buffaloes from their chenas.

We return to the hut to have our breakfast – rice pudding and tea. Ranjan is up and appears to be fairly sober. He says that today we have a long day trip to make. We head for the road, but on our way our friend is overpowered by shaking fits, and we have to leave him at a teahouse for treatment with alcoholic beverages. We see him no more this day.

In the tracker’s house, near the paddy fields, we take a break to have tea. His five beautiful daughters are busy making bundles of newly sprouted, bright green rice plants to be planted in another inundated field. They return to the house to have a closer look at the three suddhas (white people), giggling.

Their father proudly presents hides of a spotted deer (Axis axis) and a sambar deer (Cervus unicolor), bagged by him. Clearly, he supplies his meagre income with a good deal of poaching – but who doesn’t in this area, where police and other authorities are absent.

Inside the forest, we find tracks of elephants, and a sambar deer is calling. Three purple-faced langurs (Semnopithecus vetulus) are perched high up in a tree, and a couple of Malabar pied hornbills (Anthracoceros coronatus) make a racket. On the trail, we find quills of Indian porcupine (Hystrix indica).

Finally, we are in the jungle! But, alas, our pleasure is short-lived. Near a small stream lies a cluster of huts, where we get another cup of tea. Then we continue along the stream, soon entering a chena with maize plants. And then another chena with maize. And then another, and another, and so on!

Once again, we enjoy tea, served with unripe maize cobs. Gymnastics for our gums! We then return to our own maize field, where our dinner today is boiled maize cobs.

Truly a day in the sign of maize!

We get in a slightly better mood – but, after all, we have come here to see jungle.

Back at the hut, we ask him to write down how he has spent our 1,000 Rupees. He proceeds to write, but his hands are shaking so violently that I have to take over, while he dictates. After several minutes of ransacking his memory, he concludes the following:

For quite some time, Ranjan proceeds to think (if this is possible in his present condition), finally saying: “180 Rupees are personal expenses.”

He is not able to express more precisely, what ‘personal expenses’ means, but we have a qualified guess. He has absolutely no idea, where the remaining 59 Rupees are. It is a fact that he hasn’t got as much as one single Rupee in his pockets. We inform him that the value of the goods in the box hardly exceeded 100 Rupees. To this fact he gives no answer, but looks defiant and unhappy at the same time. We dismiss him on the spot.

Our hosts in the maize field haven’t been paid as much as one Rupee. On the contrary, Ranjan has borrowed money from the kind tracker, his wife informs us, when the others are out of earshot.

Niels decides to buy an old kitchen knife from the couple and pays a handsome price for it. We also hand the wife 40 Rupees, when her husband doesn’t notice, and ask her to keep the money, until we have left. She is very happy.

As it turns out, he knows Ranjan, and we are told a couple of facts about him – facts that have meanwhile dawned to us in all clarity.

“I never expected to find a type like him out here!” he says.

“He has a big mouth!” says Ranjan meekly, but without conviction.

Our new acquaintance is in charge of distributing food among settlers in this area. When a family settles here, the Sri Lankan government will supply them with basic needs, i.e. rice, lentils, sugar, and dried fish, for the first 15 months. After this period, they must fend for themselves. He talks like a waterfall and offers us arak, and when, finally, we say goodbye to the tracker and his wife, we are in a fairly good mood.

Sweat running down our back, we trot out the road towards Kuda Oya, from where we should be able to get some means of transportation to our next goal, Polonnaruwa. We are followed by the drunkard, who doesn’t utter a word – but what can he possibly say?

At a crossroad, he tries to make amends by getting us a lift on a tractor to Kuda Oya, and when we leave, he manages to mumble: “I’m sorry!”

Then we zoom along, leaving him on the road – a lost figure in the middle of nowhere.

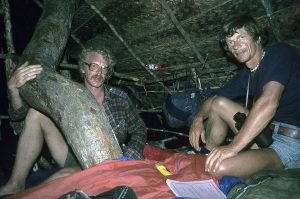

The four young surveyors, who live in this camp together with their staff, receive us very courteously. When we inform them that our goal is Polonnaruwa, they explain that there is no public transportation at all, but they promise to try to get a lift for us the following day in a jeep.

We learn a little about their working method: When they enter the jungle, a few men with guns will go ahead, at some distance followed by the surveyors with their staff and instruments. If the gunbearers meet elephants or buffaloes, they run back, as fast as they can, in which case you had better turn around and run yourself.

Walking to a nearby reservoir, we hope to see a few birds, but apart from two little grebes (Tachybaptus ruficollis) it is absolutely devoid of birds. A black-winged kite (Elanus caeruleus) swoops down to catch a mouse and settles on a branch, proceeding to tear the mouse apart, flanked by six or seven common mynas (Acridotheres tristis).

We spend the evening in the company of the surveyors. Obviously, they are happy to talk to strangers, and our conversation touches on subjects like old-age care, family patterns, weddings, salaries etc. They offer us arak and a snack of sambar meat, conserved in pure chili powder. Our throats are on fire – it is almost inedible.

Later, they invite us for dinner, rice with pumpkin curry – and the same type of sambar meat. They inform us that the deer are shot openly, although, strictly speaking, this is poaching. Well, maybe it doesn’t really matter whether the deer are shot now, or will later starve to death because their habitat is being destroyed.

Here, we pick up a number of men, one of them carrying a shotgun, as their camp was paid a visit by elephants the previous night. We continue our journey through the poor remains of the former jungle. The road is quite muddy, and there are very few bridges across the streams, so the four-wheel drive is often engaged. The men inform us that the road is less than a year old, but settlers are already pouring in. In chenas, the ubiquitous maize plants wave lazily in the breeze.

The men drop us at a crossroad, as they are going in a different direction. For a long time, we sit in this land of settlers, waiting for some means of transportation. Finally, a bus arrives, and we proceed along a bumpy road towards Kaduruwela. Late in the afternoon, we arrive in Polonnaruwa.

Our ‘jungle’ trip has come to an end.