Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Sri Lanka 1982-83: The elephant charmer

The bus passes through plantations of coconut palms and rubber trees, and along countless rice fields, where women, bent low, are busy planting pale green, newly sprouted rice plants. Small villages are dominated by huge, white Buddhist stupas, under which sacred objects are supposedly buried, maybe bones from some long dead saint. – You can read more about stupas and other aspects of Buddhism on the page Religion: Buddhism.

In a large rock on the summit is a depression, shaped like a footprint, giving rise to the Sinhalese name of the mountain, Sri Pada (‘sacred footprint’). Buddhists claim that the Buddha made the footprint when he, according to legend, visited Sri Lanka.

In Tamil, the name of the mountain is Sivanolipaathamalai (‘Mountain of Shiva’s Light’). Hindus claim that the footprint was made by Shiva, or perhaps the monkey god Hanuman.

According to Christian and Muslim tradition, the footprint was made by Adam, when he and Eve were expelled from the Garden of Eden after The Fall. Some Christians are of the opinion that it was made by St. Thomas, one of the 12 apostles.

Every day, several hours before sunrise, hundreds of pilgrims climb one of the six steep trails, with thousands of steps, leading to the top of the mountain. The goal is to be there at sunrise, when the distinctive shape of the mountain casts a triangular shadow on the surrounding plain.

“Yes-yes, my uncle rents out rooms at a low cost!” he says, guiding us through town to a house, where we are received by a small dark man, Mr. Hassiem Pusana, who is a Muslim. Indeed, he has a room for rent, and he also agrees to cook for us. He lives alone with his two children, as his wife is away, working in Jordan to make money for the family.

Our young guide asks us for a tip before leaving.

“Your nephew was kind enough to show us the way to your house,” we say.

Puzzled, Pusana looks at us, remarking: “He is not my nephew! He is just a young man from town who guides tourists to a hotel and afterwards takes commission from the owner!”

We regret that we gave the young man a tip, but it’s too late to do anything about it.

Our thoughts go to the large females, swimming about in the ocean. Every second or third year, when the time is near, unknown forces will guide them to this beach, where they themselves may have hatched thirty or forty years prior. At night, they come ashore to dig a depression in the sand above the high tide line, laying fifty to a hundred eggs in it. They proceed to cover the eggs, then camouflage the place by scraping the area around the nest with their flippers. This procedure will be repeated about every two weeks throughout the breeding season.

Their characteristic ‘tractor tracks’, however, clearly marks the position of the nest, and men from nearby villages patrol the beaches at night in search of new nests, dig up the eggs, and sell them as a delicacy. The amount they get for the eggs from one single nest is equal to a worker’s salary for two or three days. No wonder they will go far to get hold of the eggs. Not only the eggs are removed, adult turtles are also killed for their tender and delicious meat.

To prevent the sea turtles from going extinct in Sri Lanka, several reserves have been established for them. The beaches in these reserves are guarded day and night against egg robbers, and on unprotected beaches turtle eggs are dug up and moved to the reserves to be buried here. Newly hatched young are kept in captivity for a period, until they have a better chance of survival. Then, one night, they are released into the sea, far from land, to prevent seabirds and other predators from eating them.

In our backpacks, we have some goodies, and Niels has brought a bottle of liqueur from Denmark, which we share this warm night under myriads of stars, wishing each other – and the turtles – a Happy New Year.

A strangler fig (Ficus), which sprouted in a palm tree, has produced numerous air roots, which have joined around the palm trunk, hereby creating an outer ‘trunk’. The palm tree has withered and will soon rot away, leaving the trunk of the fig tree standing alone as a hollow cylinder, full of holes.

Near the coast are a number of large salt pans, in which salt water evaporates in the strong sunshine, leaving the salt behind. In these pans, many wintering waders from Siberia are feeding, such as little stint (Calidris minuta), marsh sandpiper (Tringa stagnatilis), and ruddy turnstone (Arenaria interpres).

Inland is dry scrubland with numerous cassia bushes (Senna), displaying masses of beautiful yellow flowers. Among the bushes we spot a species of climbing lily, which Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus (1707-1778) found so magnificent that he named it Gloriosa superba.

Feral water buffaloes roam the forest, and we find fresh dung from elephants (Elephas maximus). A troop of tufted langur monkeys (Semnopithecus priam ssp. thersites) are feeding out in the open, but flee into the trees when we approach too close. Star tortoises (Geochelone elegans) with beautifully patterned carapaces crawl about, and we are fortunate to watch a pair of mating Bengal monitor lizards (Varanus bengalensis).

Here and there are open areas with large lagoons and littoral meadows. In the lagoons of the Bundala Reserve, we spot two large saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus). A couple of times we have been wading across shallow water without fear, but from now on we keep a careful lookout for crocodiles. The largest specimens sometimes become man-eaters. In most areas, these dangerous reptiles have long since been shot, and today large crocodiles only survive in reserves like Bundala.

Greater flamingos (Phoenicopterus ruber) are feeding in the shallow water, head upside down, while they emit peculiar grunting calls. A peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus) suddenly appears, scaring away all the small waders, and two white-bellied sea-eagles (Haliaeetus leucogaster) pass over, emitting a mewing scream.

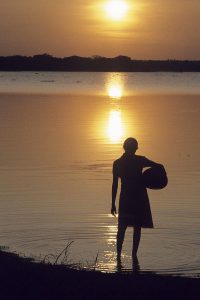

Birdlife in these tanks is very rich indeed. The largest one, Tissa Wewa, is home to thousands of cormorants of various species, dozens of lesser whistling-ducks (Dendrocygna javanica), and a few spot-billed pelicans (Pelecanus philippensis). Brahminy kites (Haliastur indus) and grey-headed fish-eagles (Ichthyophaga ichthyaetus) are soaring over the lake.

Large areas of the surface are covered by the floating leaves of lotus and water lilies (Nymphaea). On the shore, a medium-sized swamp crocodile (Crocodylus palustris) is resting, its mouth wide open. Purple swamphens (Porphyrio poliocephalus) and white-breasted waterhens (Amaurornis phoenicurus) are feeding nearby, oblivious of its presence.

Along the shore, several species of heron are feeding, together with black-headed ibises (Threskiornis melanocephalus) and open-billed storks (Anastomus oscitans). The latter has a peculiar bill – the upper mandible is almost straight, while the lower one is curved, literally causing the bill to gape. This is an adaption to feed on the main source of food for this stork – snails. While the upper mandible holds the snail in position, the razor-sharp lower mandible is thrust into the shell to cut the snail’s powerful muscles.

In a patch of tall grass, 15 to 20 male striped weavers (Ploceus manyar), whirring and buzzing, are busy constructing ball-shaped nests, weaving blades of grass together.

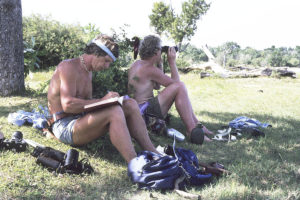

Kids run after us, shouting: “Hello, money! – Where you go? – What is your name?” They very much enjoy using our binoculars and are amazed to see how close trees and houses on the other side of the lake suddenly seem to be.

One boy points into the grass, exclaiming: “Snake!” – but he almost has to touch it, before we are able to spot it. It is a thin, green whip snake (Ahaetulla nasuta), a completely harmless species, which has a peculiar, triangular head and a long, pointed snout.

“Yes,” he says, adding: “I can charm elephants with my flute! Do you want to see it?”

This sounds very interesting indeed, so the following morning he guides us into the scrubland near the salt pans. This is where his cattle pens are situated. He is the owner of about two hundred cows, which most of the time roam freely in the scrubland. Once or twice a stray leopard (Panthera pardus) has killed one of his cows.

We follow the coast, which, in places, is covered by a carpet of creeping stems of beach morning glory (Ipomoea pes-caprae). Along the way, we pay a visit to a dozen lobster fishermen, who live on the beach in small huts, constructed of palm leaves. They haven’t brought their wives and children along. It will bring bad luck, they claim. Their only company, apart from one another, is a kitten.

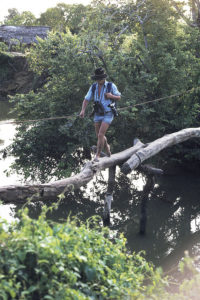

Pusana disappears into the bushes with his flute. Now he is going to charm the elephants, so we can see them! He is much too fast for us, and when we finally catch up with him, we only see the rear end of a large bull elephant, disappearing into the dense shrubs.

“I found it for you!” he exclaims, running after the elephant. We feel absolutely no inclination to follow him into these dense bushes, where visibility is perhaps 2 m, and we don’t expect to see him alive again. But he re-appears, fit and fine, saying: “The elephants won’t harm me! I can charm them!”

We trudge behind him single-file to a nearby road, where we manage to get a lift back to town in an old wreck of a car. Enough elephant charming for us!