Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Malaysia 1985: Thaipusam – a Hindu festival

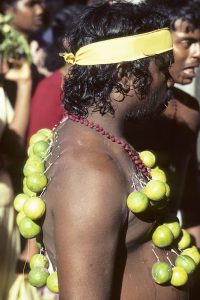

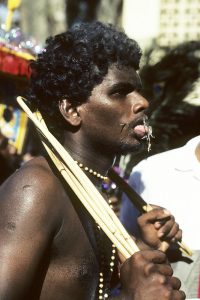

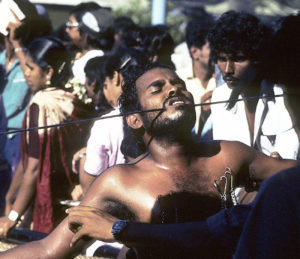

Likewise, chains are hooked to the back and chest of other male pilgrims, with oranges or lime fruits dangling at the end of the chains. The weight of the fruits will increase the pain and suffering of the pilgrim. Others have needles stuck through their tongue, or their cheeks are pierced by spears, up to 2 m long. As their mouth cannot be closed, spit is running down their chin and neck. Coagulated blood on their tongue or cheeks is supplemented with red dye to increase the visual effect.

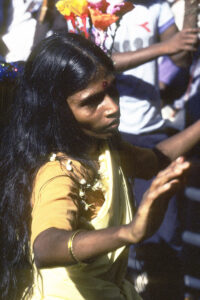

The kavadi of female pilgrims is much lighter than the men’s, almost all without hooks. Other women simply carry flower garlands or bowls with coconut milk.

During his walk, the suffering pilgrim will often stop to perform a wild dance, while his companions utter ear-shattering screams, and drummers beat their instruments to an incredible crescendo. The oranges and lime fruits jump up and down during the dance, threatening to tear open the skin. The men with spears, piercing their cheeks, hold on to the spear with both hands during their dance, to avoid their cheeks being mutilated.

This is the day of repentance, forgiveness, and hope – this is Thaipusam.

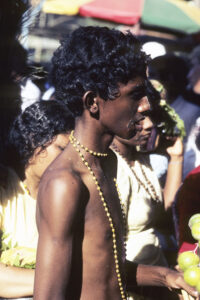

In Malaysia, Thaipusam is the most important of these festivals. Every year in February, thousands of devout Hindus undertake a pilgrimage to the sacred limestone caves of Batu, near Kuala Lumpur, to celebrate the birthday of Subramanya (‘The Spotless One’), another name of Skanda, who is the son of Shiva and his shakti (female aspect), Devi, also known by the names Uma, Parvati, Durga, or Kali. – Shiva, Devi, and other Hindu gods are described on the page Religion: Hinduism.

Thaipusam is the time to ask Subramanya to forgive committed sins, to cure an illness, or to supply luck in the future. Enduring pain and suffering, you show the god that you are willing to bring a sacrifice to obtain his goodwill.

When my companion Jette Wistoft and I arrive around 8 o’clock, a huge crowd is already gathered beneath the limestone crags, which contain the sacred caves. The level area here has been transformed into a market place with countless tiny restaurants, food-stalls, tents of traders, etc. Indian pop music is blaring from loudspeakers, the noise mingling with shouts from traders, who try to persuade people to buy their goods. The ground is littered with paper, banana peels, and other garbage.

Two small limestone caves are enclosed by a fence, and a sign outside announces Art Gallery. Before entering, each person must pay one Malaysian Dollar as a ’donation’. Inside, along the rock wall, is a long row of gypsum images, depicting Hindu gods, painted in gaudy colours and illuminated by red, yellow, blue, and green bulbs. To us, they appear awfully bombastic, but Indians, dressed up to the nines, cup their hands in front of the images in supplication, throwing coins at their feet. Every now and then, a Hindu priest comes out to collect these coins.

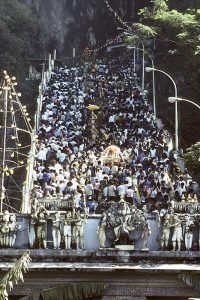

Between the river and the stairs, which lead up to the caves, the pilgrims move through a compact mass of spectators. Tens of thousands have come to watch this festival of repentance. The pilgrims, now in a deep trance, are oblivious of their presence. Foam oozing out of their mouth, they perform spectacular dances, accompanied by incredible drumming crescendos. Young men jump up to balance on the edge of huge, sharp knives, held on the ground by their companions.

Before climbing the stairs, the repenting pilgrims make a brief stop to rest, while their companions pour water on their face and into their mouth.

The stairs are divided into three sections. The central section, fenced off by thick ropes, is reserved for pilgrims and their companions. The left side is for ascending spectators, the right side for descending. Ascending the 272 steps, we move in slow-motion, chest to back, unable to do anything but follow the stream. If you lose your hat or a sandal, it is gone.

A couple of times, a group of pilgrims, with their heavy kavadi, ascend our section of the stairs, and we must scramble aside to avoid being trampled, while people shout and scream. The many police officers, who patrol up and down the stairs, try to keep a minimum of order in this inferno.

Inside, the cave is illuminated by numerous lamps, and pencils of daylight reach the floor through natural openings in the ceiling. In this cave, the ecstasy of the pilgrims reaches its climax. One last wild dance is performed, before you sacrifice coconuts by smashing them on the floor. Camphor is burned in two enormous trays in the middle of the cave. The air is nauseating, stinking of smoke, sweat, camphor, and sweet coconut milk.

At the other end of the cave, small platforms have been constructed for people to rest on. The pilgrims, who are now so exhausted that they can hardly walk, are led here by their companions. Hooks and kavadi are removed, and needles and spears are pulled out rapidly, after which ashes are applied to the wounds. The pilgrims are then taken to a small niche in the wall, where priests bless them, in return receiving small offerings of flower garlands or coconut milk.

The pilgrims are now led to the entrance and down the stairs, where long rows of beggars are seated, all the way down. They have a great day, judging from the heaps of coins in front of them.

At the foot of the stairs, the pilgrims make a brief stop to receive a drink, almost about to faint, but nevertheless happy. They have fulfilled their vow. They have endured the sufferings of Thaipusam. Surely, Subramaniya will listen to their prayer and forgive their sins, or fulfill their wish.

They can go home with a peaceful mind.