Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

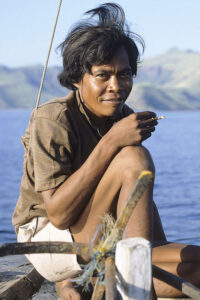

Indonesia 1985: Difficult journey to Komodo

Firstly, this species has a very limited distribution, found only on the small Indonesian islands of Komodo, Rintja, and Padar, and possibly in a very small area on the western tip of Flores.

Secondly, these small islands were uninhabited until the 1800s, when convicts were deported to Komodo – a dry, inhospitable place with a very limited supply of freshwater. The prisoners were allowed to bring women to the island, and in time a small settlement, Kampong Komodo, was established on the east coast.

Pearl fishermen, who visited Komodo in the early 1900s, spread a rumour that real dragons were living on the island. (The English may have thought the same thing, when they named it.)

Around 1910, reports concerning a ‘giant lizard’ became so persistent that the Dutch director of the Botanical Garden on Java, Mr. P.A. Ouwens, managed to persuade the governor of Flores to send an expedition to Komodo. The result was that Mr. Ouwens was able to describe this gigantic lizard scientifically in 1912.

Since I read articles about these monstrous lizards in my boyhood, I have been dreaming of seeing them. Now I have the chance. My companion Jette Wistoft and I are staying on the island of Lombok, and from here it will only take us a few days to travel to Komodo.

Driving across Lombok, the rays from the rising sun lend a pink glow to the peak of a majestic volcano, Gunung Rinjani (3726 m), the highest mountain on this island. In Labuhan Lombok, on the east coast, we obtain tickets for the ferry between Lombok and Sumbawa, and also for the bus between Alas and Bima, on Sumbawa.

In Alas, the ferry passengers disembark and board a line of busses, waiting on the pier. Almost all of them leave at the same time towards Bima, and it seems that all the drivers participate in some kind of competition. They drive like madmen on the narrow road, seemingly obsessed with the thought of getting first to Bima. I ask our driver to slow down, but a few moments later the racing bug seems to take control of him again. Finally, when we almost end up in the ditch, our Indonesian fellow travellers start shouting, and from this moment the driver is able to control himself. We continue our journey at a more sensible speed.

Now we can concentrate on enjoying the landscape. Our trip takes us along the northern coast of Sumbawa. At first, rather dry grassland dominates, with paddy fields in more fertile areas. We observe many grazing horses, water buffaloes, and Bali oxen – a domesticated form of the wild banteng ox (Bos javanicus), which lives in forested areas of Indochina and Indonesia. However, it is almost extinct in the wild. – The banteng is described on the page Animals: Animals as servants of Man.

Further east, the mountains are clad in lush forest, and the coast is quite rocky, alternating with mangrove swamps and littoral meadows. Darkness is falling, and a full moon partly illuminates the landscape.

In a losmen in Sapé, we get acquainted with an Englishman and two Swedish girls. As it turns out, they have been negotiating with a boat owner, who is willing to take them to Komodo, and back again, at a much lower price than the usual charter fee, which is around 400 US $. We join them to the harbour, where the skipper agrees to take us all to Komodo. Following further negotiations, the final price will be 17,000 Rupiah (c. 23 US $) per person.

However, now the bureaucratic machinery starts grinding. Police and harbour authorities maintain, that our skipper doesn’t possess a license to carry tourists on board his boat. Meanwhile, a German couple and their Indonesian guide have joined us, and, as it turns out, the guide is a true master of the art of negotiating. After endless discussions, we are finally permitted to leave on board the boat. Meanwhile, the sum of 30,000 Rupiah has changed hands under the table.

Dolphins are frolicking in front of the boat, and many red-necked phalaropes (Phalaropus lobatus) swim about on the water, picking tiny insects from the surface. Several species of seabirds pass by, including brown booby (Sula leucogaster), sooty tern (Sterna fuscata), and streaked shearwater (Calonectris leucomelas).

We are now close to the west coast of Komodo, which we follow southwards. The climate in this area is quite dry, causing most of the island to be grass-covered. Here and there are small groves of lontar palms (Borassus flabellifer), but forest is limited to the more humid gorges.

Now the sun is setting behind pink clouds, and soon darkness falls. An hour or so later, the moon is rising behind Komodo. We are now south of the island, passing islets and skerries. Sometimes we seem to be heading straight towards a rock, but the old man, who keeps a lookout in the stern, always manages to spot an opening that we can pass through. The wake is filled with glinting phosphorescence.

Time passes, and most of us are more or less dozing, when we finally, around 10 P.M., arrive at Kampong Komodo, a cluster of huts, situated in a sheltered cove. The Indonesian passengers disembark, and a lot of cargo is unloaded. The boat then continues a bit further north along the coast, to the national park headquarters. It’s past midnight, before we have been registered and given rooms.

Then, in the company of a national park ranger, we walk along the beach, where a tame rusa deer (Cervus timorensis) follows us like a dog. Along the shore, a whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus) and two or three common sandpipers (Actitis hypoleucos) are feeding.

Now we leave the beach, making our way into the forest, through shrubs of jujube (Ziziphus), Albizia, Hibiscus, and others. In this area, we encounter a number of bird species, including green imperial pigeon (Ducula aenea), black-naped oriole (Oriolus chinensis), and the endangered yellow-crested cockatoo (Cacatua sulphurea).

Finally, we arrive at a clearing, where a large sign announces the following, ”Dangerous area – Watch out – Komodo crossing – Be silent!”

When tourists visit the island, the national park staff will usually use slaughtered goats as bait, to make sure that the tourists are able to observe the giant lizards. The previous night, our group has also bought two goats. [This practice has since been banned by the national park authorities.]

We have reached the feeding area, where a safe enclosure has been constructed for the tourists. (On several occasions, Komodo dragons have attacked – and eaten – people.) In a dried-out watercourse, a large lizard is already waiting, and others soon come running. They look so slow and clumsy, but are in fact surprisingly fast and agile, easily able to outrun a person.

Now one of the goats is slaughtered and hung up in a tree, whose branches reach out over the riverbed. The dead animal is lowered, and immediately the giant lizards start fighting furiously to get the best parts of the carcass. They quickly manage to open the belly, gorging themselves on the intestines.

By now, eight of the greedy lizards are gathered around the carcass. Two monsters, more than 3 m long, each grab a leg, while an even larger fellow manages to twist off the head of the goat and swallow it. Only tidbits are now remaining, and the other goat is hung up in the tree. When, in no time, the monsters have finished eating this one, too, they lie down in the hot sand, with distended bellies, to start digesting. Now they don’t have to eat for several weeks.

The largest of the lizards are greyish-brown, with pale, diffuse rings down the tail, whereas younger animals are more colourful, with pale spots on the hindneck and down the sides of the neck, and yellowish rings on the tail. A small specimen, which the rangers manage to catch, has even brighter colours.

On our return journey, we travel north around Komodo, where we have a fine view of the islands Rintja and Padar, which are also part of the national park. The strong current is against us most of the way, and our trip to Sapé lasts almost 12 hours. A highlight on the way is two beautiful white-bellied sea-eagles (Haliaeetus leucogaster), soaring over us.

Darkness falls, and the night is warm, with plenty of heat lightning.