Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

India 1982: Pleasures of Nanda Devi

Thus, our journey into this beautiful area was made in the nick of time. Today, the national park is still closed to all but a few select scientists. In 1988, it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

He relates a hike, which his uncle once undertook to a nature reserve in the Himalaya, called Nanda Devi Wildlife Sanctuary, named after the highest mountain in Garhwal, Nanda Devi (7816 m). To visit this sanctuary, you have to make a very interesting hike up the Rishi Ganga Valley.

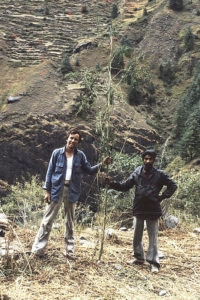

Ajai has planned to go there himself, and he kindly invites me to join him. I believe this would be an interesting hike for an American friend of mine, John Burke. I write a letter to him, and after some library research he decides to join us. In October 1982, we all meet in Delhi.

We hire a taxi, struggling to lift the heavy boxes onto the roof rack. We then take our seats, and off we go towards the small town of Joshimath, deep in the Himalaya.

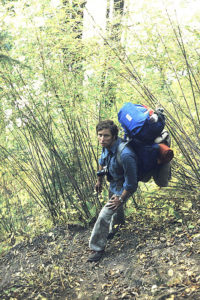

The following day, we board a local bus to the village of Lata, where our hike is going to start. It is impossible for us to lift the two heavy boxes onto the roof-rack of the bus, so we hire a local porter to do the job. He squats beside one of the boxes, tying a rope around it and then around his shoulders. Muscles taut and sweat pouring down his face, he manages to get up and then climbs up the ladder to the roof of the bus. This procedure is repeated with the other box. We pay him the handsome sum of 10 Rupees (1 US $), and he is very pleased indeed.

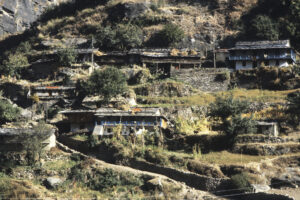

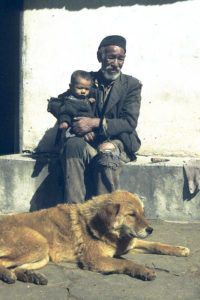

A dominating feature in the village is a Hindu temple, outside which grows an enormous Himalayan hemlock (Tsuga dumosa). Branches of this tree are used as decoration during festivals. Cultivated plants in this area include rice, buckwheat, and amaranth. After being harvested, the crops are spread out on the roofs to dry.

Our camp is situated on a plateau near the Rishi Ganga River, and when we are not busy with preparations for our hike, we study the bird life in the river, which includes blue whistling-thrush (Myophonus caeruleus), white-capped river-chat (Phoenicurus leucocephalus), and brown dipper (Cinclus pallasii). Shrubs along the river harbour birds like green-backed tit (Parus monticolus), red-headed bushtit (Aegithalos concinnus), and yellow-breasted greenfinch (Chloris spinoides).

When our preparations have been completed, we head out of Lata, following a trail along fields to Belta, and thence up through lovely forest of various trees, including Himalayan cedar (Cedrus deodara), West Himalayan yew (Taxus contorta), walnut (Juglans regia), and a species of whitebeam (Sorbus).

John has been walking a little distance behind Ajai and me, and when he catches up with us, he relates a strange encounter he had on the trail. As he was struggling along with his heavy backpack, he noticed one of our porters, an elderly man, lying beside the trail, utterly exhausted. When he saw the white sahib, he opened his mouth, pointed down his throat and exclaimed: “Vitamin E!! Vitamin E!!”

The steep trail continues through the forest, which is now dominated by fir (Abies) and shrubs of Rhododendron campanulatum. Our porters have made camp on a ridge named Lata Kharak, from where we have a wonderful view towards the surrounding mountains, including Dunagiri (7066 m), Trisul (7120 m), and Hathi Parbat (6727 m).

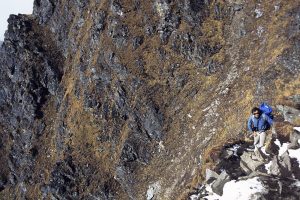

Atop the pass, a narrow trail runs across a stony plateau. Our porters are already far ahead, with the exception of a nice fellow named Gabar Singh, who is waiting for us and now leads the way.

Ajai, who is a student and maybe not so fit, is now very tired, lagging behind. When we notice that he is sitting on a rock, we go back to find out what’s wrong.

He refuses to move, saying: “Just leave me here. I’ll spend the night here. I can’t go on.”

“Don’t be ridiculous, if you stay here, you’ll freeze to death!”

“Oh no, I can’t go on,” he insists.

A snow storm is looming on the horizon, and we decide that I am going to walk in front of Ajai, while John walks behind him, pushing him forward, every time he tends to slow down. To do this, John has to abuse him, calling him nasty names, which makes Ajai angry, and the produced adrenalin somehow makes him able to continue.

Darkness is falling, and we still have to negotiate a steep, muddy slope down to our campsite. On our way, we must often cling to branches. John slips, tearing his trousers on a rock.

In the very last light of the day we struggle into camp near a big rock, under which our porters have decided to spend the night. Gosh, what a day! Ten hours of hiking – the toughest walk we have ever made.

We get company from an Indian climbing expedition, and one of the climbers is this gorgeous girl from Calcutta. Ajai immediately forgets his tiredness and babbles away with the girl for an hour or more. That night we sleep like logs.

The following morning, we find fresh tracks of leopard (Panthera pardus) outside the camp.

We thought that we could make it into a circular valley, called ‘The Sanctuary’, which is surrounded on all sides by tall mountains. However, we soon get wiser.

We encounter two members of an expedition, who have just climbed a spectacular white granite mountain named Changabang (6864 m) (see photos at the top of this page). They inform us that to enter ‘The Sanctuary’ we have to deal with “treacherous snow on treacherous ice on treacherous rock,” as they vividly express themselves.

This scares us off, and, following the advice from our porters, we decide to camp a few days near the great Bethartoli Glacier, situated in a side valley, which leads up to Trisul Base Camp.

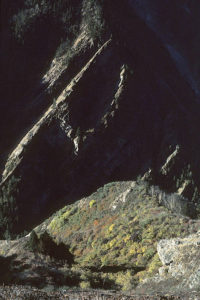

Leaving a part of our equipment and food in a crack between two rocks at Deodi, we continue our hike through a lush birch forest, where the branches of the gnarled and twisted trees are covered in old man’s beard lichens (Usnea). – A fascinating account of these lichens is found on the page Quotes on Nature.

Himalayan vultures (Gyps himalayensis) and lammergeiers (Gypaetus barbatus) soar above us, and in the forest we observe passerines like blue-fronted redstart (Phoenicurus frontalis) and spot-winged tit (Periparus melanolophus). A Himalayan bluestart (Tarsiger rufilatus) is feeding among the stones.

In the evening, we all gather beneath the slanting rock, our staff singing Garhwal songs, which I record on my tape recorder. I place my hand in hot ashes, but a large blister is the only harm done.

During the night there is heavy snowfall. A Himalayan queen fritillary (Issoria issaea) is sitting on the fresh snow, and near the glacier we find pugmarks of a snow leopard (Uncia uncia). This superb cat, which is only found in mountains of Central Asia, has diminished drastically in most areas, and today the total number may be less than 5,000.

The cloud cover lifts, and soon most of the snow has vanished. The yellow whitebeam leaves are covered in a layer of snow, and when this snow begins to melt, the leaves drop to the ground, where they form a brightly coloured carpet on the snow.

With great care, we cross the Bethartoli Glacier to explore the Trisul Nala Valley. Gabar Singh, who is leading the way, suddenly comes to a stop, uttering only one word: ”Bharal!” On the mountain slope across the river, a herd of 26 beautiful blue sheep (Pseudois nayaur) are feeding. This species is an evolutionary curiosity, as its behavior shows traits from goat as well as sheep. On our way back, we surprise four of them on the trail in front of us. They bolt, uttering a peculiar, bird-like call. However, they soon calm down, allowing us to approach quite close.

Throughout our hike, I have been on the lookout to photograph the impressive lammergeier, or bearded vulture. One day I go out to collect firewood, and to look for Himalayan musk deer (Moschus chrysogaster). Meanwhile, John is lying in the grass, reading a book. When I return, he says: “While you were away, this huge bird landed in a tree about 50 yards from me. It was reddish and had hanging, beard-like feathers around the bill. What bird is that?”

I almost feel an urge to hit him!

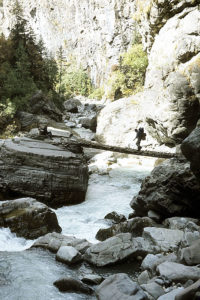

As we now follow the Rishi Ganga River out of the area, we won’t have to cross the awful Dharansi Pass, but otherwise the trek is far from easy. Descending sheer rock walls, we have to dangle on ropes, and several times we must cross the Rishi Ganga, balancing on logs. Gabar Singh, in his black, shiny ballroom shoes, just dances over these logs like nothing, but John and I are scared stiff while crossing.

On a particularly nasty ‘bridge’, consisting of rather thin logs which balance precariously on larger rocks on either side of the river, John stops halfway across, clinging to another log with both hands. Gabar Singh has to go out and help both of us ashore.

Finally, we reach agricultural areas, where sheep herders invite us for tea. Late in the afternoon, Gabar Singh points to a harvested field, saying: “This is a good place to camp.”

John leaves to explore the field, but quickly returns, exclaiming: “Holy shit, we are going to camp in a marihuana field!”

When we reach Gabar Singh’s village, John gives him his sneakers, so that he’ll not have to wear his black ballroom shoes on future hikes. Later that day we meet him in the street, clad in his best finery: Super-clean clothes and John’s sneakers.