Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Syria & Iraq 1972: “Welcome to Baghdad!”

”Are you the one watching birds?”

“Yes.”

”And you have planned to go to Iraq by car?”

“Yes.”

”Can I join you?”

Together, we now plan our trip. We buy a second-hand Volkswagen van, construct sleeping berths in the back, buy a gas stove, put clothes and several books into a few old wooden beer crates – and off we go. We are very young and very inexperienced travellers, ignorant of red tape. Just before leaving, we learn that we need to bring a carnet de passage – a document which ensures that when you bring a foreign car into a country you also export it again, unless you want to pay import duty.

We commence our journey in late October, and as the nights are quite cold, we drive briskly southwards. Finally, in southern Yugoslavia, the nights become pleasantly warmer.

One day, near the town of Titov Veles, we notice some griffon vultures (Gyps fulvus) and golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos), soaring over the mountains. To have a better view of them, Arne pulls out his telescope and mounts it on a tripod.

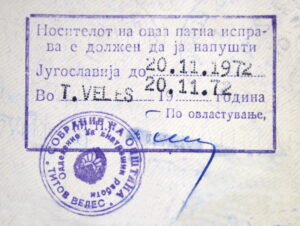

As we are enjoying the birds, a car comes to a halt in front of us, and a couple of grimly looking police officers alight from it. Using sign language, and a few German words, they make it clear to us that we must follow them to the police station in Titov Veles. Here we learn that it is not allowed to stop, where we were watching the birds, and that photography is strictly prohibited.

“We didn’t take any photographs, we were just watching some birds in our telescope.”

They refuse to believe us, and I must hand over the film roll in my camera, my protests being of no avail. The police officers then put a stamp in our passports, ordering us to leave Yugoslavia the same day. This is not a problem, as a couple of hours’ driving will bring us to the Greek border. We hastily leave the unfriendly police officers.

“They are not quite right in their head!” says Arne.

In Istanbul, a ferry brings us across the Bosporus Strait to the Asiatic continent, where we head for central Anatolia. It is now November, and the nights are bitterly cold. We therefore hurry towards the dramatic Taurus Mountains and the Syrian border.

This city is dominated by a huge citadel, built in 1171 by an Egyptian sultan of Kurdish descent, Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub (1137-1193), founder of the Ayubide Dynasty. This sultan, in the West known as Saladin, became famous for his many victorious battles against invading Christian crusaders.

Every morning before dawn, the muezzins call for prayer. “Allah-u-akbar! As-hadu-an-la-ilaha-il-Allah! Muhammadun-rasul-Allah!” (“God is great! I announce: There is no god but God! Muhammad is God’s servant!”) From loudspeakers, placed in high slender towers, minarets, the calls boom across town, reverberated by the house walls.

According to the Holy Quran, devout Muslims must pray five times a day. This can take place anywhere, on Fridays – the weekly Muslim holiday – preferably in a mosque. Before you pray, you should wash your face, hands and feet.

Prayers are performed partly standing, partly kneeling, and partly lying down, your forehead touching a small prayer rug. During the prayer, your face must point in the direction of Mecca, Saudi Arabia. In this city, a square building, the Kaaba, contains a sacred black stone, probably a meteor, which was revered long before the foundation of Islam.

The first prayer, al fajr, must take place at the crack of dawn, when there is enough light to distinguish a black thread from a white one. The other four prescribed prayers take place at noon, in the afternoon, when the sun is at an angle of 45 degrees with the horizon, at sunset, and two hours after sunset.

We inhale wonderful fragrances from spices and herbs, like garlic and mint, ginger and paprika, rosemary and cardamom, and exotic spices, unknown to us. Huge piles of apples, oranges, pomegranates, and other fruits are displayed, handed over by unveiled women to their customers who haggle over the price.

In front of tea houses, small groups of men sit and talk while sipping strong, sweet tea from small, slender glasses. The mouthpiece of a big gurgling water pipe is handed from one man to the next in turn.

In other streets, we experience other smells – exotic, too, but not quite as enjoyable: donkey urine, dog shit, and sometimes even human faeces. The river running through the city is a black mess of sewage and garbage, stinking awfully.

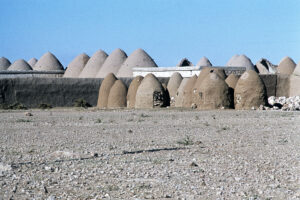

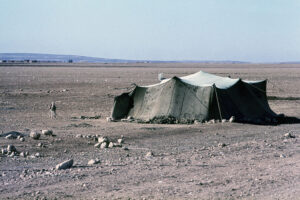

The landscape is far from being monotonous, alternating between sandy desert, rocky outcrops, bush steppe, and arable land, displaying all possible shades of yellow and brown. Village houses are plastered with mud, making them blend remarkably well with the surrounding landscape. Here and there are amazingly green oases with date palms, orange trees, and tamarisks – a great contrast to the more subtle colours of the desert. We make a brief stop to talk to several men, who are training their falcons.

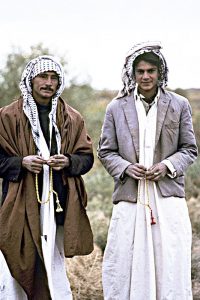

A fellah (farmer) in this area invariably wears a head-cloth, often tattered, and a grey or brown jellaba, a pyjama-like garment, reaching down to his ankles. A thick cloak, an abba, is often draped over his back to ward off the winter cold. The more affluent men wear a kefia, a red-and-white or black-and-white scarf, kept in place on the head by an agal, a thick, black rope with tassels at the end, which often dangle over his shoulders.

The women’s dress, which almost reaches the ground, is either black or with flower design. Veils are not used in this area. When they spot us, a couple of women pull down their black scarves to cover their faces. Other women hand us hrobes, freshly baked pancake-shaped loaves, proudly refusing to accept any payment. ”La-la!” (”No-no!”) they say, waving their hands deprecatingly.

“As-salaamu-aleikum,” (“Peace upon you”) they greet us, to which we reply: “Aleikum-as-salaam.” (“Upon you peace”) They want to know, what we are doing in Syria and where we are going. Some of them bring cassette players, and we experience the distinct Arabic music and songs.

In the restroom is a cistern, its brand written in raised letters: ‘The best Niagara’. There is no water in it, and the presence of plenty of rust reveals that the waterfall has ceased to flush several years ago. Arabian toilets are usually just a hole in the floor, over which you squat. In the wall near the hole is a water tap with a jug, which you fill up, using the water to clean yourself, always with your left hand. For this reason, the left hand is considered unclean, and you must always eat and receive items with your right hand. This is very inconvenient for Arne who is left-handed.

At the border control post, we realize that we have made a grave mistake. The imposing immigration officer scrutinizes our passports for some time, and then says: “Mister, where are your visas for Iraq?”

Visas? We thought we would get them at the border, like we did when entering Syria. We spend some nerve-shattering hours on a bench, while the immigration officers call their boss in Baghdad to ask, whether or not we must go back to the Iraqi consulate in Halep to get visas. Just before dusk, the big officer hands us back our passports, saying: “Mister, go to Baghdad, to the Residence Department. You will get visas there.”

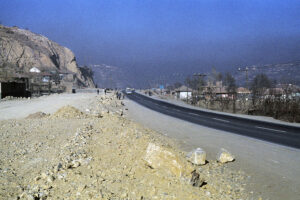

We spend the night in our car on the premises of the border post, and next day, all day long, we drive towards Baghdad along unbelievably bad dirt roads, sporting enormous potholes, protruding stones, slanting surface, etc. Top speed is sometimes as low as 15 km/h.

Eleven exhausting hours later we reach Baghdad, where we find accommodation in a modest hotel.

Now we have to find the Residence Department. When we arrive, we are ushered into a dull, damp office, in which three uniformed officials are seated behind their desks. One of them scrutinizes the paper we were given at the border, finally asking: “Mister, how long do you want to stay in Iraq? What is your purpose of coming here? Where do you stay in Baghdad?”

We explain as best we can.

“Mister, you can only get visas for one week.”

They instruct us to go up one floor to another office to get a signature. Someone here informs us that we need photographs for the visas. I sprint back to our car, which is parked 500 yards away, collect the pictures and hurry back to the office, only to find out that we have to wait a further quarter of an hour. From Office No 2 we are sent to Office No 3, the ultimate castle of registration. The shelves are absolutely stuffed with folders and ring binders. A clerk flips through an almost infinite number of these, muttering our names. After ten minutes, he gives up and signs the paper we have brought.

“Mister, go to the next room.”

In Office No 4 we get yet another signature.

“Mister, go downstairs.”

Yes, sir. While descending, we mutter in Danish, cursing bureaucracy. “They are not quite right in their head!” says Arne again.

In Office No 1, the same official is suddenly much more positively inclined.

“How many days do you need? Is one week enough?”

“Can we get two weeks?”

“Are two weeks enough?”

“Can we get a month?”

“No, then you must go to our embassy in Kuwait.”

We readily accept this, in order to get away from this place. A new formula has to be filled in.

“Go to the president.”

In a somewhat more sophisticated office we get the signature of the ‘president’. Then back to Office No 1 for a control.

“Go to the president again.”

Back to the noble office again for a control. Then down to Office No 1 for yet another control.

“Go upstairs with the papers. Welcome to Baghdad!” says the official and salutes.

In Office No 2 we get a stamp in our passports: ‘Emergency visa’, for two weeks – and they never wanted our photographs. Utterly exhausted, we leave the building.

“They are not quite right in their head!” says Arne yet another time.

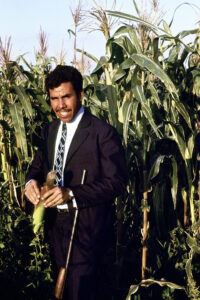

Following the exhausting experience in the Residence Department, we decide to go to Aziziyah and try to find Muhammad. Arriving in the small town, we seek out the address, given in the magazine. Here we are received by a friendly agricultural consultant, named Salman, who speaks fairly good English.

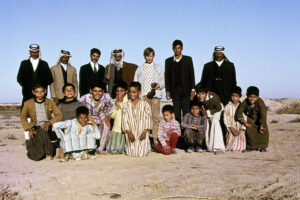

While we drink tea, he informs us that Muhammad is now working in Baghdad, and then asks if he can do anything for us. On learning that we would like to visit farmers in the surrounding area, he willingly brings us to several villages during the follwing days. Everywhere, we are received with great hospitality, enjoying tea and even meals. We also make friends with several students in Aziziyah, who drag us around to friends and family.

An immense contrast to the difficulties in the Residence Department!