Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Sri Lanka 1975: An illegal walk through Wilpattu

The vegetation in Wilpattu mostly consists of rather dry scrub forest, which is nevertheless home to a surprising variety of wild animals, including Asian elephant (Elephas maximus), leopard (Panthera pardus), wildboar (Sus scrofa), several species of deer, feral water buffalos (Bubalus bubalis), Bengal monitor lizard (Varanus bengalensis), marsh crocodile (Crocodylus palustris), and a large number of various water birds. The park also harbours ruins from ancient Sinhalese cultures.

It is now our intention to repeat this hike, accompanied by Sarath’s friend Siva, who is a Tamil. We board a bus from Colombo, heading north, and from the small town of Puttalam, another bus brings us around a large lagoon, through vast plantations of coconut palms (Cocos nucifera). These trees are very hardy, growing in pure sand, as long as there is enough water underground. In large pans, salt is extracted from sea water, which evaporates in the strong sunshine, leaving salt behind. We also pass small saltwater ponds, where various waders are fouraging, including Kentish plover (Charadrius alexandrinus) and black-winged stilt (Himantopus himantopus).

The soldier relates that he and his colleagues, not so long ago, made a hunting trip into Wilpattu, where they shot a deer and a wildboar. Sarath is of the opinion that the marine soldiers can do whatever they want, as the park rangers are probably afraid of them.

The following day is a Sunday, and as this area is mainly inhabited by Christians, no ferry will leave for the small island of Karativu. Instead, we arrange with some fishermen, who are going to the island this evening, to take us there – for the huge amount of 70 US Cents for the three of us. The fishermen load their boat with various items, including wooden beams, palm leaves for thatching, and diesel for the boat engine. Huge flocks of ring-necked parakeets (Psittacula krameri) pass over Kalpitiya, heading inland, while numerous house crows (Corvus splendens) fly the opposite way.

My companions take their seat on top of the engine hull, whereas I am a bit more comfortable on a pile of palm leaves. Heading north, the boat passes several islets, covered in mangrove, which serves as night roost for numerous great white egrets (Ardea alba) and little egrets (Egretta garzetta). The sun sets over the ocean, adding an orgy of red to the sky. A clear planet is seen, but there is no moon at all. After a while, stars begin to appear.

We pass a number of small boats, with lamps tied to the stern, which attract fish. Small waves wash over the rail, and in the wake from the stern, phosphorescent glimpses are emitted. The wind increases in force, causing spray from the stern to run down our face and hindneck. Soon we are more or less drenched.

From our packs, we bring out two loaves of bread, and one of the men brings a bowl of delicious fish curry. The men also serve arak – alcohol, made from palm toddy, which is quite potent. The rest of the evening we chat with the fishermen, until it is time to go to sleep.

Karativu is only inhabited during the fishing season, and most of the fishermen’s wives and children remain on the mainland. The village here consists of about a hundred huts, constructed of branches, covered with palm-leaf mats. Some huts are completely open, others are equipped with walls, made from palm leaves. Coconut palms, low and windblown, grow among the huts. Numerous fish have been spread out on mats to dry in the sun, protected against crows and dogs by fine-meshed nets.

These fishermen are Catholics, and a small church has been constructed on the island. As today is Sunday, the men are not going out fishing. Instead, they sit in small groups and talk, while they repair their nets. The cost of a large net is around 30,000 Rupees (c. 3,000 US$), but just three lucky fishing trips are able to pay for it.

The beach near the village acts like a garbage dump. Among the rubbish, we spot yellow sea snakes, small dolphins, and porcupine fish with a ball-shaped body, densely covered in spines. Without a cooling wind, the stench would probably be overwhelming.

A man and his daughter are searching for edible creatures on the mud flats, where redshank (Tringa totanus) and whimbrels (Numenius phaeopus) are feeding. A yellow bittern (Ixobrychus sinensis) moves adeptly about among the arched air roots of a mangrove tree. Numerous small holes in the mud are inhabited by fiddler crabs (Uca), the males waving their one huge, brightly coloured claw, partly to attract females, partly to mark their territory.

Sea turtles are protected in Sri Lanka, but on this remote island, the fishermen can do as they please.

At lunch time, we are served rice and a meat curry.

“How do they get beef out here?” I ask foolishly.

Giggling, Sarath says: “It’s meat from the butchered turtle!”

It is delicious, so maybe it is not so strange that the fishermen ignore the law and catch the turtles.

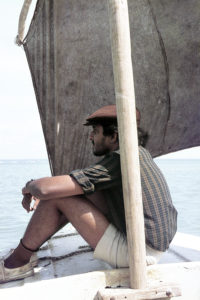

We have arranged with a fisherman to bring us to the coast of Wilpattu National Park, not so far away. He sets sail and places an outboard engine on the rail, after which he lies down to sleep, leaving the rest of the work to an adolescent boy. During the trip, small waves wash over the rail, but in the intense heat our wet clothes soon dry again.

On our way through the dense scrub forest, we observe a number of birds. A white-bellied sea-eagle (Haliaeetus leucogaster) passes over, and a woolly-necked stork (Ciconia episcopus) takes off from a tree. Numerous blue-tailed bee-eaters (Merops philippinus) and smaller green bee-eaters (M. orientalis) zoom along the trail, hunting for insects, and ring-necked parakeets utter their shrill scream. A beautifully patterned star tortoise (Geochelone elegans) crawls about on the trail, and in several places the soil has been overturned by wildboar, searching for tubers. When our guide is convinced that we can find our way, he leaves us.

Late in the afternoon, we arrive at a large clearing, in which some fifty spotted deer (Axis axis) are grazing, accompanied by several gorgeous peacocks (Pavo cristatus). At the other end of the clearing lies a large bungalow – staff quarters of the national park. From this building, two rangers walk briskly towards us.

“What are you doing here?” one of them exclaims, ”Don’t you know that it is illegal to enter this park on foot? You will have to pay a fine!”

The quiet and dignified behaviour of my companions quickly calms down the rangers, and when they learn that I am a Dane, one of them says: “Of course, he is not aware that it is illegal.”

The rangers are not nearly as angry, as they might want to be, and later they invite us to spend the night on the verandah in front of the bungalow – provided that we promise not to leave the dirt road the following day. Naturally, we agree to this. We place our loads on the verandah, where we sit down to enjoy the view.

At dusk, ten or fifteen wildboar emerge from the forest to graze in the clearing. By now, the rangers have become very friendly. They lend us a small lamp, so that we don’t have to cook in the dark, and we borrow a coconut scraper which allows us to make sambol (bits of copra, onion, salt, chili powder, and lemon juice). Nobody is talking about fines anymore.

Down the road, a travelling tradesman has made camp, with his ox and cart. Most of these traders are Muslims, called moors, who travel around in remote parts of Sri Lanka, selling kitchenware, ammunition, and other commodities. Instead of cash, they often receive local goods, for example animal hides, crops, and honey from wild bees.

Before setting out, we eat a hurried breakfast. We are facing a walk of about 30 km, as we have promised the rangers to be out of the park the same day. During our walk, large sambar deer (Cervus unicolor) flee into the dense scrub forest, and we often hear the barking call of Indian muntjacs (Muntiacus muntjak) – small reddish deer with very short antlers. Twice we observe golden jackals (Canis aureus) on the road. They stare at us for some time before running away.

Finally, the dense forest opens up to wide expanses of swampy meadows with numerous waterholes. A herd of water buffaloes sniff the air, snorting when they catch our scent, whereupon they turn around and gallop into the forest, making a tremendous racket. Great white egrets and pond herons (Ardeola grayii) are feeding at the edge of the waterholes, among huge piles of elephant dung. We take a break to cook lunch – potatoes, boiled in dirty lake water, and served with marmalade.

Continuing our walk, we observe several troops of two species of monkeys, the tufted langur (Semnopithecus priam ssp. thersites) and the toque monkey (Macaca sinica). Grizzled giant squirrels (Ratufa macroura), with enormous bushy tails, climb about in the trees, and a large star tortoise with three big humps on its carapace creep about on the trail.

In a small cabin, inhabited by rangers, we get water to make tea. The rangers inform us that we have yet 5 km to walk before reaching the Kala Oya River, which marks the southern border of the national park.

“Is it difficult to cross the river on foot?”

“No, you won’t have any problems. The water level is very low, because the December rains were very scarce.”

At dusk, we reach Kala Oya. This place looks so inviting that we decide to sleep on a sand bar in the river. Before cooking our dinner, we have a refreshing bath in one of the few pools that still remain in the riverbed. We light a fire, adding numerous sticks to it to keep the mosquitoes at bay. An owl hoots from a tree along the river bank, and in another camp downstream somebody is playing a flute. Satisfied and at peace with ourselves and the world, we fall asleep.