Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

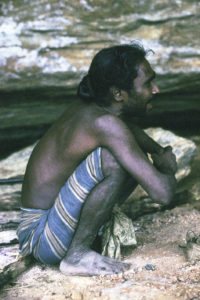

Sri Lanka 1974: Among Veddas

The Sinhalese soon converted to Buddhism. According to legend, Buddhist preacher Arahat Mahinda arrived at Mihintale, near Anuradhapura, c. 250 B.C., where he met King Devanampiyatissa, who was out hunting. The king became interested in this new philosophy and decided to convert to Buddhism. A monastery was built at Mihintale, and a large rock out in the open was elected as ’information rock’. From this rock, monks were informing the old gods about the new thoughts.

Mahinda had many conversations with the king, once saying: “Oh, Great King! The birds of the air and the beasts have an equal right to live and move about in any part of this land as Thou. The land belongs to the peoples and all other beings, and Thou art only the guardian of it.”

Apparently, these wise words did not count for the Veddas, who were driven into remote mountains and jungles in the eastern part of the island. Around 1163, the Veddas are mentioned by King Parakramabahu, who calls them Kiratas, meaning ’wild hunters’ in Sanskrit. He employed several of them as warriors. Buddhism preaches non-violence, but nevertheless various kings fought each other viciously. The irrigation systems were destroyed, the artificial lakes turned into muddy pools, and malaria killed the majority of the population. The jungle conquered the Sinhalese buildings, and the Veddas got some of their old hunting grounds back.

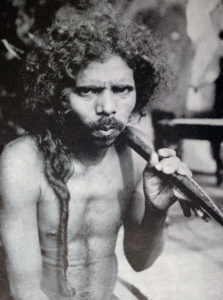

Later the Portugese, then the Dutch, and finally the British took control of the island. In 1681, Robert Knox writes about the Veddas: ”They kill deer, and dry the flesh over the fire, and the people of the country come and buy it of them. They never till any ground for corn, their food being only flesh. They are very expert with their bows. They have a little ax, which they stick in by their sides, to cut honey out of hollow trees.”

Numerous tales have been told about Tissahami, a famous Vedda, who lived near Maha Oya in the 1930s. Together with his two wives, a Vedda and a Sinhalese, he lived on a small piece of land, growing crops, which they sold to travelling tradesmen. Tissahami and his eldest son were both very hot-tempered, and in a dispute with another man they killed him. They were declared outlaws, and the family fled into the jungle, always moving about to avoid the authorities. Finally, his wives and children had enough and left him, moving to the small hamlet of Pollebedda. Only his eldest son stayed with him, and they fled into the most remote parts of the jungle. The son died, but Tissahami disappeared completely. He was declared dead, but many years later he suddenly emerged from the jungles, and lived to a ripe old age.

Today, there are probably no pure-blooded Veddas left, as they have intermarried with Sinhalese and Tamils. They now make a living as farmers, cultivating crops like maize, manioc (cassava), and chili in chenas (clearings) in the jungle. Occasionally, the men hunt sambar deer (Cervus unicolor) and wildboar (Sus scrofa), and they gather honey from wild bees. From a certain tree, they collect the sweet fruits, which are considered a great delicacy. Unfortunately, the Veddas cut down these trees to gather the fruits, and this species has become very rare.

Scattered in the landscape are huge banyan trees (Ficus benghalensis), with numerous stilt roots. Malabar hornbills (Anthracoceros coronatus), hill mynas (Gracula religiosa), and toque monkeys (Macaca sinica) feed on their tiny fruits. In the scrubland we observe many other birds, including blue-tailed bee-eater (Merops philippinus), Indian roller (Coracias benghalensis), ring-necked parakeet (Psittacula krameri), brown-headed barbet (Psilopogon zeylanicus), and black-winged kite (Elanus caeruleus).

It is very hot, and we make a brief stop to ask a farmer for water. He hands us oranges to quench our thirst. We walk briskly, covering about 12 kilometres before reaching the hamlet of Pollebedda, just before dusk. We are allowed to spend the night in a small school, which is wonderfully cool, as it has only one end wall, while the other three sides are open. We enjoy our dinner, spaghetti with melted cheese and sardines. It tastes better than one should imagine – but then we are hungry.

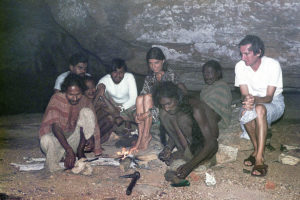

After dark, many people from the village gather to talk with us. Four of them are of Vedda origin, and they agree to be our guides the following day, showing the way to a huge rock in the jungle, Nuwaragala, where, not so long ago, Veddas used to live on rock ledges. An old prankster entertains us with songs, which Sarath, one of our Sinhalese companions, writes down, giggling. He refuses to translate for us!

Colourful butterflies flutter about in the clearings, and hornbills make a tremendous noise. A beautiful Sri Lanka junglefowl (Gallus lafayetii) crosses the trail in front of us, and a sambar deer flees into the forest. In a dried-out watercourse, we find tracks of wild elephants (Elephas maximus) and Indian porcupines (Hystrix indica). Many other animals live in this jungle, including wildboar, sloth bear (Melursus ursinus), purple-faced langur, and the strange slender loris (Loris tardigradus), a small primate with large eyes and long, slender limbs.

Occasionally, we make a stop to pull off blood-sucking leeches, which cling to our legs. On its head, a leech has a sucking pad, and when it senses your body heat it quickly tries to attach itself to your skin. If it goes unnoticed, it cuts into your skin with its sharp mandibles to suck your blood. You don’t feel anything, but the wound will bleed copiously, itching terribly. Otherwise, there are no effects of the bite.

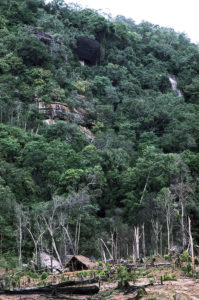

Twice we pass chenas, where the forest has been burned and maize planted among the black stumps. At the end of one chena is a small palm-thatched hut, containing only a few kitchen utensils. They belong to people from Pollebedda, who occasionally come here to tend their crops. In the intense heat, we start ascending the huge Nuwaragala rock. A rope ladder is dangling down the rock face, used by Veddas, when they collect honey from wild bees, which often build their nest on sheer rock walls.

Atop the rock are the remains of an ancient Sinhalese culture, including a water reservoir, which was carved out of the rock. Here we quench our thirst, afterwards having a refreshing swim. Numerous frogs, water beetles, and other small creatures swim about in the water, and a huge pile of dung indicates that wild elephants also drink from the pool.

“Can elephants really get up here?” I ask Sarath.

“Oh, yes,” he answers, “elephants are very adept at climbing quite steep rocks.”

This rock ledge is an old Vedda dwelling, approximately 25 metres long and 10 metres wide. Along the outer edge of the ceiling, a small furrow has been carved to collect rainwater, which would otherwise drip down on the floor. From this furrow, the water drips into another furrow on the floor, from where it is directed over the edge. At one end of the ledge, rainwater is led from yet another furrow into a small pool, acting as a source of drinking water.

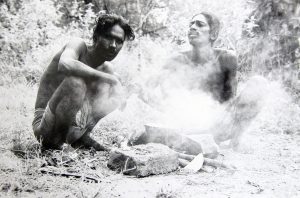

Our guides ignite a fire to give us some warmth, and to dry our clothes. Finally, the rain ceases, and the surrounding mountains can occasionally be seen through clouds, which the fierce wind blows upwards to our ledge – where they dissolve as if by magic. To the south-east is the ragged top of a mountain, named Friar’s Hood, and we get a glimpse of a huge lake, Senanayake Samudra, in the distance. Small Indian swiftlets (Aerodramus unicolor) zoom along the rock face, hunting for insects.

We enjoy our evening meal, huddled around the fire, while a chorus of frogs start croaking from the small pool on the ledge. Then we creep into our sleeping bags, as near to the fire as possible, as the wind is still very cold. The Veddas keep the fire going throughout the night.

The following morning, we return to the Sinhalese reservoir. In the wet forest, we find baskets and the remains of a fire, and soon we meet a few men from the village, who are out to gather forest fruits. They inform us that the previous evening they had been unable to find our rock ledge, and were forced to spend an uncomfortable night, huddled under a small, overhanging rock.

By now, our water supply is almost exhausted, and we approach a small house to ask for drinking water. The owner hands us water of a dubious colour, but we are very thirsty, so we drink it anyway. The family are settlers who have been given 5 acres of land. Maize grows well here, but, unfortunately, the area is malaria-ridden. One of their sons is lying on a mattress on the floor, sick with a high fever. We hand them malaria tablets and a little money, so that they can take the sick child to the doctor by bus. “Ayobowan,” says the man as we leave, hands cupped in front of his face.

Exhausted, we reach Maha Oya, just as ominous black clouds cover the sky. However, only a few drops of rain fall.