Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Iraq 1973: The hospitable mudir

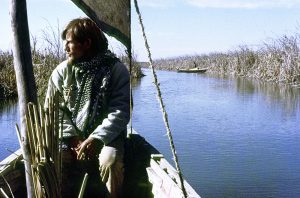

In this town, my companion Arne Koch Christoffersen and I hope to be able to hire a boat and a man to punt it, as we intend to go into the marshes to watch birds, and also to visit the Madan, a people of mixed origin, whose way of life is completely adapted to the wetland they live in.

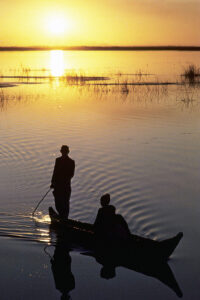

There are almost no roads in the marshes, and to get around you must go by boat. Most boats here are long, slender canoes, called meshof. Motor boats arrived as late as the 1960s, and they are still a relatively rare sight.

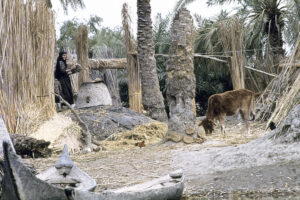

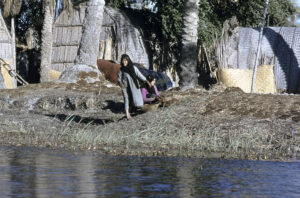

The Madan make a living by growing rice, raising water buffaloes, and by hunting and fishing. Their houses are constructed of reeds, either along the shores of the waterways through the marshes, or on islets.

So we head straight for the police station, greeting the officers, “As-salaamu-aleikum” (‘Peace upon you’).

“Aleikum-as-salaam. (‘Upon you peace.’) Sit down.”

As always, no matter where and for what purpose you have come, sweet, strong tea is served in small glasses. There is no hurry. The officers scrutinize our passports and carefully note our names in a big book – in Arabic. Arne’s surname, Christoffersen, is somewhat troublesome to them. They want to know what our professions in Denmark are, what we are doing in Iraq, and of course why we have come to this place.

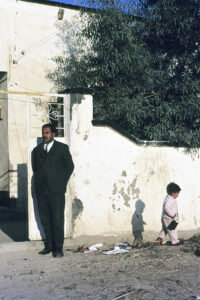

When they learn that we would like to visit the marshes, they instruct us to talk to the mudir, who is away at the moment. A mudir is a town leader, a kind of mayor, but also the head of the police force.

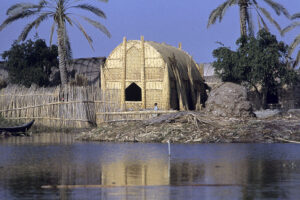

Meanwhile, we drive a short distance to the shore of Hoor al-Hamar. Several houses, with walls plastered with sun-dried mud, are lined along the shore, together with a few mudhifs (guest houses).

A mudhif is constructed from thick, tightly bound bundles of reeds (Phragmites australis). The base of these columns are buried two and two opposite each other, forming two rows. Then the tops of the bundles are bent towards each other and tied together, thus forming a row of arcs, and thick mats, likewise made from reed, are tied to these arcs. The end walls are also made from mats, tied to vertical reed bundles.

Along the shore, many meshofs are tied to poles, and further out in the water, several large, black, snorting water buffaloes are submerged, with only their heads above the surface.

Various birds are feeding in the shallow water, including black-tailed godwits (Limosa limosa) and black-winged stilts (Himantopus himantopus). Pied kingfishers (Ceryle rudis) hover above the water before diving headlong into it. If one bird succeeds in catching a fish, the event is eagerly commented upon by its companions.

Two men are heating lumps of tar over a fire, applying the liquid tar to the hull of a leaking boat. They use a round stick to produce a thin, smooth layer. The tar is from Hit, in central Iraq, where open tar pits are found.

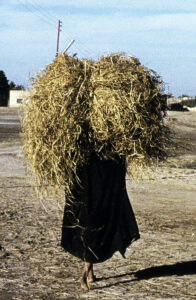

A couple of women are winnowing wheat. Slowly, they pour the grain from a basket onto mats on the ground, so that the wind can blow away dust and chaff. Nearby, another woman places cakes of dried cow dung over a tuft of dry grass, lights a fire and places a kettle over the fire to heat water for tea. Several women pass by, carrying big bundles of fresh reeds or hay on their head, to be used as fodder for the cattle.

A kind school teacher negotiates for us with a man, named Hawas, who is willing to bring us in his boat into the marshes the following morning.

At dusk, large flocks of night herons (Nycticorax nycticorax) leave their day roost, heading into the swamps to feed. Behind them, the sky is a brilliant orange.

“Would you like … to drink … the Pepsi,” he suddenly asks. Yes, why not. We drive to a small restaurant, despite the fact that it is only a few hundred yards away. You must arrive in style.

While we drink ‘the Pepsi’, he entertains us with a monologue, commenting on the imperialistic ways of the Coca-Cola Company in the Third World. His English is somewhat erratic, with a break after every two or three words, leaving him time to find the next few words.

“No, you must … drink … the Pepsi,” he concludes. We look at each other and refrain from commenting. We haven’t got his permission to go into the marshes yet. But, as it turns out, the mudir does not at all object to our plans.

He invites us for dinner in his house some distance away along the shore, so off we go in our van. He leads us into a basic room, furnished only with a few rugs, on which we take our seats. The meal is already served on a rug in the centre of the room. We make rice lumps, using our right hand, dipping the lumps in a delicious mutton stew. Water is served with the food. When the mudir has had his fill, he tosses the remaining water in his glass into a corner.

After dinner he wants to hear our opinion about the Palestine conflict, and he also wants to know more about our country. Denmark must be an imperialistic country, because we are a kingdom.

He points to our beard and says: “You must cut this … you blame the girl!” He himself sports a short, prickly moustache and day-old stubble, but it seems that this will not do any damage to a girl’s cheek.

We have brought along Wilfred Thesiger’s excellent book The Marsh Arabs, which the mudir now studies with interest. However, he finds it all immensely primitive and is highly offended by some pictures of naked boys.

When we ask permission to sleep in our car, he instructs us to park for the night in front of the police station.

Initially, our trip brings us along narrow waterways through the reedbeds, which, besides the ubiquitous reed, contain large stands of clubrush (Schoenoplectus) and bulrush (Typha), whose downy seeds are carried by the wind in the thousands. The water surface is covered by white, fragrant water-crowfoot (Ranunculus aquatilis). Squacco herons (Ardeola ralloides) and goliath herons (Ardea goliath) take flight, uttering raucous calls. Over the reedbeds, marsh harriers (Circus aeruginosus) glide effortlessly, searching for prey.

Out in the open, the lake surface is partly covered by water lilies (Nymphaea) and other plants with floating leaves. Large flocks of great cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo), white pelicans (Pelecanus onocrotalus), tufted ducks (Aythya fuligula), shovelers (Anas clypeata), and coot (Fulica atra) take flight, when we get too close, and little grebes (Tachybaptus ruficollis) dive, or skate along the surface, uttering their trilling call. Above us soar white-tailed sea-eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla) and greater spotted eagles (Aquila clanga).

A man, punting his boat through the water lilies, is singing loudly, and two younger men a busy placing a fishing-net in the cold water, which reaches up to their thighs.

A boat approaches us, punted by two men who have been cutting hashish, fodder for their buffaloes. They wear pyjama-like garments, which they have rolled up, to be able to move about more easily. Another boat contains two hunters, who have shot some coot. Distant shots are heard from other hunters.

When a man catches sight of us, he comes down to the shore, and after our mutual greetings he invites us into his house. A woman is busy making pancake-shaped loaves, applying them to the inside of an oval clay oven, the inside of which is heated by embers. The embers heat one side of the loaves, the hot wall of the oven the other, and they are baked in a few minutes. Leaning against the house wall are several buffalo dung cakes, drying in the sun, later to be used as fuel.

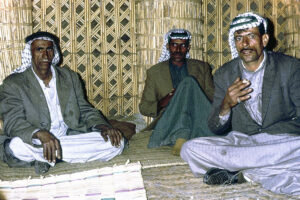

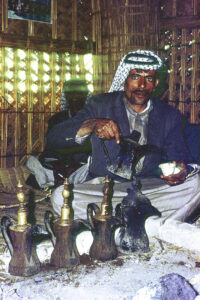

Before entering the mudhif, we kick off our shoes. Inside, several men are seen dimly along the walls. After our mutual greetings, we walk around to shake their hands. Three beautiful rugs are placed around a fireplace in the centre, on which are several coffee pots and a tea pot, all blackened by smoke. We are seated on cushions along a wall.

Muhammad had only one child, a daughter, and the Shi’a acknowledge Muhammad’s son-in-law Ali, who was also his cousin, as his first true heir, and Ali’s sons Hassan and Husain as the next two heirs.

In 681 A.D., Husain and his followers travelled to Iraq to fight against the Khalif of Damascus, who claimed that he was the true heir of Muhammad. At Karbala, Husain and his men were all killed in a battle, and Husain became a martyr for the Shi’a Muslims.

The foundation of the Shi’a Islam is related in detail on the page Travel episodes – Iran 1973: In the mountains of Luristan.

From the kitchen on the other side of the wall, smoke seeps into our part of the mudhif, and we hear women talking. Sheep are bleating outside, and a slight wind causes the reeds of the mudhif to creak.

A young man now pours kerosene over a few dung cakes, and soon flames are licking up around the tea pot. Meanwhile we are served coffee, following an ancient ritual. A few drops of strong coffee are poured into a cup, not much bigger than an egg cup. This is repeated twice. After drinking the third cup you shake the cup, signalling that you have had enough. A packet of cigarettes and matches are placed in front of each of us, while Hawas is questioned about our purpose of coming here.

When the tea is hot, we are served first, being guests. An elderly, blind man is lead into the mudhif by a boy. After the usual greetings our host shouts: “Sabakkum-alab-el-khrer” (‘Good morning’), the blind man answers, after which all the other men (and we) greet him in a similar way.

A few minutes later, we thank our host, commencing our return trip to Hamar.

Again, the mudir invites us for dinner: “In some hours … you must come … to my house … to eat breakfast.”

When we are seated, he says: “Tonight … we eat … the meat … from … eeeerh? – Get your book, get your book!”

Arne goes to our car to fetch our bird book, which the mudir has been studying earlier, and now he turns the pages, until he finds the plate, depicting ducks. We are served rice and teal.

After dinner we have a long conversation with the mudir. His English is poor, and yet each subject must be covered in detail. Obviously, he has heard about something, called ‘free sex’, and is very eager to hear more about it. He wants to know whether we in Denmark “… do it … from the back … or from behind.”

We glance at him questioningly, and he repeats. Finally, I must get up. He pats me on my back and says “back.” Then he pats me on my stomach and says “behind.”

Oh, that’s what he means!

We ask the mudir for permission to stay a few more days in Hamar, as we would like to go on several trips into the marshes. Not only does he readily agree to this, he also invites us for dinner every day and instructs his wife to prepare lunch for us. This is served by his beautiful sister-in-law at our car, which is parked at the lake shore near their house. She is unmarried and therefore allowed to show her face to strangers. But we have not seen his wife yet – not as much as a glimpse.

One day, we pay a visit to a green-domed tomb, a qubba, the final resting place of Said Esa. Said is a title, which only descendants of the Prophet are allowed to use. Such persons are revered, and it is quite remarkable, how many people claim to be descendants of him!

Relics of the deceased are often buried under a qubba, and Shi’a pilgrims, who visit it, bring gifts for his relatives. (This may very well be a good reason, why Muhammed has so many ‘descendants’!)

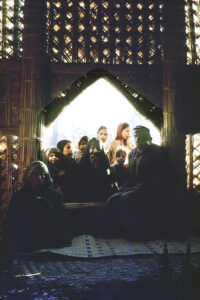

We place our shoes outside the building and enter. In the centre of the room is a platform, covered by a multi-coloured cloth, on which lie several Qurans, wrapped in green cloth. Small, brown ‘stones’ are sacred, hardened clay from Karbala, where the Shi’a martyr Husain is buried.

We spend the evenings with the mudir, eating and talking. One evening, three police officers join us. The mudir tears a chicken into two halves, handing us one of them.

“When you … have finished this … you must take … from this!” he says and points to the other half, which he is going to share with the three other men.

Another evening, a student arrives during our meal to talk to the mudir. After our formal greetings, the mudir asks us: “Why don’t you … kill him … to eat?”

We look at one another, bewildered. Why should we kill and eat this fine young man? Finally, it dawns to us that the mudir means “call him to eat”, i.e. invite him to join our meal.

Later, the mudir asks: “Did you see … my wife … last night?”

“No, we didn’t.”

“Why not? She saw you … while you … wish your hands!”

Back at our van, Arne and I agree that she must have been peeping through the semi-open door, while we were washing our hands before the meal.

As time goes by, the mudir seems to gain some confidence in us. His wife, a pretty woman about thirty years old, is now allowed to serve the food and to talk to us. Her English is by far better than his!

Time and again, the mudir directs the topic of our conversation to Scandinavian girls, which seem to fascinate and repel him at the same time. He confides to us that he is indeed attracted to the mode of super-short skirts. Yet, his own wife and sister-in-law wear garments that almost reach the floor. A woman, who has been visiting his wife, leaves the house, wearing an enormous black veil, which covers her face entirely. You should definitely not look at the face of another man’s wife!

The chief of the local police force arrives one evening to discuss something with the mudir. The wife brings our tea, unaware that the policeman is there. The mudir jumps up to take the tray, while the policeman hurriedly turns his face away.

One evening, when we are alone with the mudir, he leans forward and confides to us that there is a matter, which he has been giving some thought.

“If I … in Danimark … kissink a girl … and with her … doink anythink … and she … after some months … this …” (Here he shows a big belly with his hands.) “What then?” he says, looking at us expectantly.

Arne and I look at one another, not knowing whether to laugh or weep. We try to explain that in Denmark all lone mothers are supported by the government, if the father is unknown.

Believing that he has misunderstood us, he says: “It may mean … if I … in Danimark … kissink a girl … and with her … doink anythink …” (The whole thing is repeated). “Then … the government of Danimark … will pay?”

“Yes.”

The mudir’s eyes bulge to an extent, that we fear they will leave his skull.