Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

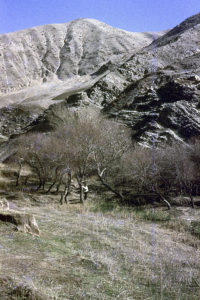

Iran 1973: In the mountains of Luristan

Today, the vast majority of the Lur people are farmers, but a few still live a semi-nomadic life, grazing their sheep and goats in the mountains in the summer and in the lowlands in the winter.

In these mountains, my companion Arne Koch Christoffersen and I intend to spend the rest of the winter. We left Iraq without regret. The eternal suspicion, with which the government officials were watching our whereabouts, had become a nuisance. We hope to experience a more relaxed time in Iran.

The dried-out rivulets are full of oleander bushes (Nerium oleander), from whose open seed pods thousands of downy seeds fly about. Caspian pond turtles (Mauremys caspica) swim in the brooks, innumerable frogs are croaking, and pied toads crawl about. Down in the valley, along the river, farmers are ploughing their fields with oxen.

A metre-long desert monitor lizard (Varanus griseus) is creeping up a rock face, and here we also observe blue rock thrushes (Monticola solitarius), black redstarts of the red-bellied subspecies (Phoenicurus ochruros ssp. rufiventris), and rock pigeons (Columba livia). Herdsmen are grazing goats and sheep high up on the slopes. The animals are surefooted, but occasionally they cause a shower of pebbles to tumble down. Over the highest mountain peaks, which are still clad in snow, golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) are soaring, whereas griffon vultures (Gyps fulvus) and lammergeiers (Gypaetus barbatus) patrol the valleys in search of carcasses.

We spend a week in this area and then proceed north to Khorramabad, the capital of Luristan. As it turns out, this city is definitely not a nice place. Garbage and dung litter the streets, and also the river, where women wash carpets by stomping on them in the icy water. Boys clean our car windows, without us asking them, and demand money afterwards. The town is teeming with beggars.

Even though spring is near, the mornings here are bitterly cold, the vegetation covered in rime. We don’t want to drive through Iran now, as we hope to get into contact with Lur nomads. As a consequence, we drive south again. We stop in a minor town to do some shopping. An elderly lady with henna-coloured hair grins to me and slaps me on the shoulder, while she strokes her chin and points to the sky. I guess that she is asking whether I am a priest, since I grow a full beard. (In Iran, only priests have full beards.)

“My father has sent me to ask you to come to our village,” he says. Finally, what we have been hoping for is happening.

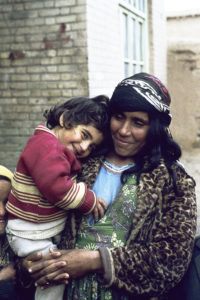

The village is not far from the road, connected to it by a muddy track. We drive into the yard in front of a large brick house. Most of the other houses in the village are made of large stones, with a plaster of mud. The roof consists of thick willow branches, covered with several layers of reed mats. A horde of children and an unveiled woman, around 35 years old, appear from the house. Everybody is smiling, and we are received very courteously. People from the neighbouring houses also appear to have a look at the strangers. We enter their guest room, where the floor is covered by a beautiful carpet. The mother serves us tea.

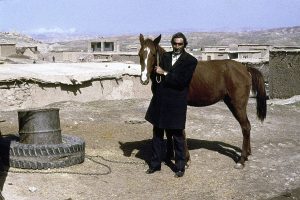

Some hours later, the man of the house enters, clad in a huge European coat. He presents himself as Muhammad, khan (chief) of the village. He is 52 years old, with grizzled hair and a long, hooked nose. He lives with his present wife, Badri, and seven of his twelve children. Ali, his eldest son, is 20, the daughter Maria is 16, the four sons Ardishir, Mamakru, Husain, and Reshik are 15, 12, 10, and 7, and his youngest daughter is only one year old. His other children stay with their mothers, whom Muhammad has divorced.

Muhammad speaks a fair bit of English, learned while working for an American oil company. His English is certainly very colourful, containing many phrases, which don’t belong in ball-rooms.

“I tell my fucking son, go tell these people come to my house. Not good sleeping in the mountains – wolf, leepard,” he says. He has noticed that we usually park in strange spots to spend the night, and as the head of this village he doesn’t want anything to happen to us in his area.

We inform him that we have come to his land, among other things to look for wolves and ‘leepards’, and we have no fear of these animals. He digests this piece of information for a while, and then says: “Loose man! Not good sleeping in the mountains!” Oh, so that is the problem! He is afraid that bandits will attack us during the night.

Muhammad disappears into the stables, returning with his pride, a red horse. We must say hello to him, too. The family invites us for dinner, rice and fried eggs. We eat in a separate room, whereas the members of the family eat in an adjacent room.

Later in the evening, it seems that half of the population of the village have gathered in the guest room, and the subjects of our conversation are the usual ones: Where do we come from, what are our professions, where are we going, what are we doing in Luristan, etc. Muhammed invites us to spend the night in the house, and we collect our sleeping bags from the car.

We take a stroll along the fields, where green wheat sprouts have just emerged. Muhammad notices that some calves have escaped from their enclosure and are now happily grazing in the wheat, and he gives an order to one of his sons.

“I tell my fucking son, go get them calves out of my wheat!” he says.

We continue our walk to a small lake at the far end of the fields. One of Muhammad’s sons has saddled the red horse, riding ahead. Poppy anemones (Anemone coronaria) and cranesbill (Geranium) are blooming among the grass, and colourful butterflies flutter about. In the lake, several hundred ducks and coot (Fulica atra) are feeding. A couple of men are driving a large herd of cattle and donkeys towards the village.

Muhammad soon gets tired and wants to go home to eat lunch. He mounts the horse, places his youngest son in front of him, and rides along the stony path, singing loudly and out of tune.

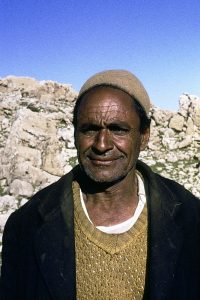

To some extent, people here have adopted European garments. Women wear a frock, with big, baggy trousers underneath – tight trousers would be bothersome, as much of their work is done squatting. Almost all the men wear baggy trousers, a shirt, a European jacket, and on the head a small felt cap.

We spend the evening in the guest room, listening to songs and music from our cassette player. Muhammad wants us to record one of his songs. He is definitely not a good singer, but out of politeness, we let him fill an entire tape and wear out some batteries, while he delivers a long speech in praise of Shah-in-Shah Muhammad Reza Pahlevi and his Queen, lying on his back on a blanket with his long, dangling legs woven into one another. He is too lazy to get up, so every half an hour he shouts: “Maria!” – a signal to his daughter to come and re-arrange the cushions under his head.

Minutes pass, an hour passes. Still no Muhammad. Finally, he appears, but seems a bit distant. No more talk about cartridges, and we wonder. We return to Mirabad. The following days, this procedure is repeated, and then, finally, he confides to us that he is an opium addict. The house, which he enters every day, is a place, where opium with a revenue label is sold. However, only elderly men with a special permit can smoke opium legally. Sometimes we doubt if Muhammad possesses this permit.

A week later, we are fully accepted, and by now he smokes openly in the yard. He spreads out a small rug and cushions, lies down, and proceeds to prepare the pipes. The opium is ignited with a piece of glowing charcoal from the fireplace. Some days earlier, we have been talking about the first landing on the Moon, a few years prior. After enjoying five or six pipes, Muhammad points at his pipe and says: “This is my Apollo! Now I’m flying to the Moon!”

The eldest son declares that opium is his father’s batteries – nodding towards the cassette player.

In the evenings, we listen to our tapes, and Muhammad fills several of our empty ones with new speeches in praise of the Shah. One evening we have no more empty tapes, and we convey this fact to the old man. After digesting this piece of information for a while, he says: “God damn! Don’t know what’s the matter you not tell me no more tube! I will buy!”

Muhammad is a bit of a hypochondriac. Invariably, he claims that something is wrong with his miserable body, but in spite of this he jumps about like a goat. Time and again we hear about his bad teeth, but when we are served mutton, he eats more – and faster – than we do. He often complains of headache, but when we offer him a pill, he declines.

A venereal disease is not high on our priority list, so we politely decline his offer to get ladies. After a pensive moment Muhammad declares: “Irani queen got good pussy!”

We wonder how he knows.

Moving in these circles, Muhammad tells us a true story from the neighbourhood: A man in a nearby village had brought a small donkey to bed with him, because he wanted ‘jig-jig’. But the donkey got entangled in the blankets and escaped with them. Another man noticed this, fired his gun into the air, and shouted: “Wolf! Wolf!”

Everybody in the village came running, and when they saw the entangled donkey, they had a great time. The owner claimed that he knew nothing about it, but nobody believed him.

In 681, Husain and his followers went to Iraq to fight against the Caliph of Damascus, who claimed that he was the true heir of Muhammad, selected by a council of elders. The Shi’a did not acknowledge this choice, maintaining that only God could appoint Muhammed’s heirs. In a battle at Karbala, Husain and his men were all killed, and from this day, the Caliphs of Damascus, and later Baghdad, held the power within Islam.

The Shi’a fervently commemorate the death of Husain. In his book Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegenden Ländern (Gloyer und Oldshausen, Hamburg, 1837, in English Travels Through Arabia and Other Countries in the East, Performed by M. Niebuhr, Gale Ecco, 2018), German cartographer and mathematician Carsten Niebuhr gives a vivid description of a group of pilgrims, paying a visit to the tomb of the martyr in Karbala, in present-day Iraq: “I was genuinely puzzled by watching the devotion, with which the superstitious people already in the front yard kissed the entrance door, and also later kissed the door of the mosque. Inside the temple, they eagerly kiss the floor, and I was told with conviction that to some devotees the death of Hössein is so sad that they hit their head agains the wall and the iron grids. It has been told that some devotees have become so mad with rage that they have killed themselves at their great imam’s grave, believing that they will also be recognized as martyrs, and go to heaven, because they have given their life for the sake of Hössein. I must confess that I have never heard anything more plaintive than these devoted Shi’a. People screamed and howled as if Hössein had been their father and had been murdered this day; this was by no means false, like the professional mourners who weep over a deceased for money, but so genuine that the eyes of those who left the mosque were swollen from crying.”

Instead of the caliphs, the Shi’a acknowledge a succession of 12 imams, all descendants of the Prophet. They maintain that the 12th imam, Muhammad ibn Hasan al-Mahdi (868-941), disappeared, but will return in due time as the ultimate saviour of mankind and, together with Isa (Jesus Christ), bring peace and justice to the World.

In 818, the 8th imam, Ali ibn Musa al-Riḍha (in Iran known as Imam Reza), was murdered by order of the Abbasid Caliph, al-Ma’mun. The place he was buried was called Mashhad al-Ridha (‘Martyrdom of al-Riḍha’), and in the late 9th Century, a dome was erected on the grave. Later, numerous other buildings were built on this place, today constituting the largest Islamic temple complex.

During a break we are offered tea and sugar-water – the latter having religious significance. While the men resume their beating, the women are seated in the next room, gossiping and smoking a bubbling water pipe. Later, the imam recites from a holy book, and when he is reading the chapter, which describes the death of Husain, the men bury their face in their hands, sobbing loudly. (Some days later, the same imam reproaches Muhammad for taking non-believers into his house. Muhammad is not affected, but replies that the holy Quran instructs you to be hospitable to all strangers – regardless of their race or religion.)

The following morning, a large group of men and boys are gathered in front of a mosque in Mirabad. They carry a large standard, depicting Husain’s horse, and many garments are tied to a long pole, depicting a woman from Husain’s house. The head is made of wood and covered in black cloth. On her chest and back are pictures of Husain and his family. She weeps because Husain has gone to war. “Where is Husain?” she shouts, her voice belonging to a local boy. The procession then proceeds to the next village.

”God damn, Mr. Arne, Mr. Kaj,” says Muhammad. ”Today, we go in your car to Shush, very nice festival.”

Consequently, we drive south with six men from the village, all crammed into our van. We spend the night in Andimesh, continuing early next morning to Shush, where a large drama is performed, depicting the slaughter of Husain and his men. From each and every minaret, imams recite from holy books through loudspeakers, their blaring mingling to an infernal noise.

In a huge, bare field, thousands of people are gathered, all dressed in their fineries. Many policemen are patrolling to keep a minimum of order. One of them instructs us not to take photographs, but one of our friends from Mirabad offers to take them for us. At one end of the field sits a man with a green scarf, depicting Husain, whereas the colourful men at the opposite end depict followers of his enemy, Sunni Caliph Yassid.

Horsemen depict Husain’s men, who ride into battle and get killed by Yassid’s men. Husain’s brother Abbas rides. Reputedly, he was able to perform miracles. Men and women now bring their children to the actor to have them blessed by the touch of his right hand. When he is ‘killed’, people around us start sobbing loudly, tears streaming down their face. Many run across the field to collect soil from the spot, where Abbas ‘fell’. They bring home this soil to eat it, as medical properties are ascribed to it.

Climax of the show is reached at noon, when Husain himself is ‘killed’. The ring of spectators narrows, and when Husain’s ‘body’ is carried away, people stream to the place, where he was lying, to collect soil.

The leader bids us welcome, and we are seated on carpets in one of the tents. The canvas is kept in position by several thin wooden poles, the sides of the tent tied to big rocks with strong ropes. Along the sides are low stone walls, made wind proof by stuffing grass between the rocks. A fire is burning in the centre of the tent, kept alive by adding a few dried branches now and then. We are served tea. Soon several men from the other tents join us, all clad in European clothes. By contrast, most of the women wear the original Lur garments – coarse black cloth, decorated with silver coins and other jewellery.

Inside the tent are enclosures, made from interwoven thin willow branches. Here lambs and kids are kept during the night and in bad weather. They have many enemies in these mountains: Wolves and golden eagles are common, and we are told that a leopard took five lambs a few weeks ago. The men tried to shoot it, but didn’t succeed.

Black clouds build up, and a lot of lambs and kids are ushered into the tent, all bleating as they try to enter the enclosures simultaneously. Rain starts pouring, and a few drops sprinkle through the canvas. Outside, a lamb is slaughtered, and the meat is carried into the tent, where it is roasted over the fire on large spikes. With the mutton comes rice and bread. The meal is delicious.

New clouds look threatening, and Muhammad is of the opinion that we should leave, as the road might become impassable for our car. However, the road is a perfectly fine gravel road, so we justly suspect that the old man’s true reason for wanting to leave is that we should go to town, so that he can get his daily ration of opium.

The following day we return to the nomads’ camp to watch them dismantle their tents and load them onto donkeys, together with big baskets, which contain kitchen utensils, chickens, puppies, infants, and more. Off they go, following stony paths to nearby grazing grounds. The women walk beside the donkeys and urge them forward with sticks, while the men drive their flocks of sheep and goats a shorter, but more difficult route, which the donkeys cannot negotiate with their heavy loads.

We drive into the mountains to spend some time in natural surroundings. A few days later, we are again invited to a village, hidden behind the hills. The road leading to the village is horrible. Our new host guides us across his yard, where a couple of ferocious dogs are barking like crazy, tugging on their chain. Soon 15-20 men are gathered in the guest room, enjoying the Lur music, which we play on our cassette player. They listen attentively to Muhammad’s praises of the Shah, nodding and exclaiming: “Balle! Balle!” (“Yes! Yes!”)

We drink tea, and they invite us to stay for dinner, which turns out to be a chicken so tough that we can hardly pull the meat from the bones with our teeth. In the evening, numerous sheep and goats are ushered into the yard, which is soon filled with animals. A man guides us to the toilet across the yard to make sure that the terrible dogs won’t eat us. We are invited to spend the night in the house, and our host brings out quilts and blankets for us.

Early in the morning, our host ignites a fire. With a knife he chips bits of sugar from a big lump, adding them to warm milk. It tastes lovely with bread. We thank him and continue our journey into the mountains.

Three days later, I discover that we are no longer only the two of us in our car. I’ve got lice.