Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Iran 1973: Car breakdown at the Caspian Sea

Here and there, rows of poplars break the monotony. High up in the trees, rooks (Corvus frugilegus) gather around their nests, calling raucously – a sign that spring is just about to arrive. Imperial eagles (Aquila heliaca) and black kites (Milvus migrans) are soaring above in search of food.

However, a harsh wind still blows dust and dirt about in the streets. When they have finished their shopping, women hurry home, pulling their chaddor down to cover their face. Houses here are unheated and damp, causing women and children to huddle around the fireplace in the kitchen, while they prepare their meal.

The foothill streams, tumbling down from the mountains, are swollen with melt water. Along their banks we observe white-throated dippers (Cinclus cinclus) and white wagtails (Motacilla alba). In patches, where the snow has melted, colt’s-foot (Tussilago farfara) and lesser celandine (Ranunculus ficaria) are already in bloom, and small tortoiseshells (Aglais urticae) suck up the heat from the spring sun.

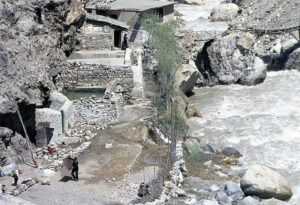

Along the rocky mountain side, people still live in caves. The road climbs steadily, surrounded by snow-covered fields. Snow-fences have been erected along the road, but nevertheless we occasionally encounter large stones, lying on the road.

On our way, we pass snow-clad Damavand (5671 m), the highest mountain in Iran. The road heads through tunnels and over mountain passes, before diving into a dense cloud cover on the north side. Here the climate is almost sub-tropical, the mountain slopes covered in rich forests of broad-leaved trees, including oriental beech (Fagus orientalis) and species of oak (Quercus), maple (Acer), and poplar (Populus), the majority already sporting fresh, green spring foliage.

Birds abound in this forest, and various mammals also live here, including roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), fallow deer (Dama dama), brown bear (Ursus arctos), and grey wolf (Canis lupus).

For two days we are parked near a small stream, waiting for the pouring rain to stop. Everything is wet, very wet. But despite the weather, birds are singing merrily, including chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs), winter wren (Troglodytes troglodytes), song thrush (Turdus philomelos), blackbird (Turdus merula), and robin (Erithacus rubecula). In the evening, the hooting of a tawny owl (Strix aluco) is heard.

Flowers also abound here, and on short trips along the stream we find flowering primroses (Primula), vetches (Lathyrus), and violets (Viola).

The Caspian Sea is home to a large number of fish species, including the sturgeon (Huso huso), which supplies Shah Muhammed Riza Pahlevi with caviar. This product seems to be so important to him that he keeps most of it to himself, whereas most of his people live in poverty. In this inland sea you also find a species of seal, the Caspian seal (Phoca caspica), which lives nowhere else on Earth.

Near the foothills, huge areas have been converted into rice fields, and at this time of the year, ploughing is taking place. We make a stop near a small canal, in which numerous marsh frogs (Pelophylax ridibundus) are croaking. Dice snakes (Natrix tessellata) are basking in the morning sun, and we also see a legless lizard, or scheltopusik (Ophisaurus apodus), a relative of the slow worm (Anguis fragilis). A man, who is passing by, approaches us to see, what we find so interesting. I make twisting movements with my hand, causing him to smile.

“Hreli!” (”Many!”), he says, resuming his walk. In a village we stop to buy food. Its houses are constructed of sun-dried bricks, plastered with mud. Groundsels (Senecio) are blooming among the straw on the roofs.

The fertile strip of land stretches almost to the shores of the Caspian Sea, replaced by rows of low, greyish sand dunes. Depressions among the dunes are covered in vegetation, primarily prickly tufts of a species of rush (Juncus). The beach is hard and smooth, and thus very good to drive on. At the water’s edge, various waders are feeding, including greater sand plovers (Charadrius leschenaultii), Kentish plovers (C. alexandrinus), and dunlins (Calidris alpina).

In the south-eastern corner of the lake is a 70-km-long sand spit, Mian Kaleh, pointing east, hereby creating a large inlet, named Gorgan Bay. On their northbound migration in spring, numerous birds follow the shoreline, concentrating in numbers at this sand spit. Before we continue our journey towards Afghanistan, we would like to study this bird migration.

Along the shore, we encounter the occasional cluster of fishermen’s huts, and flat-bottomed boats are hauled up on the beach. Twenty or thirty fishermen are busy pulling ashore a huge net, full of fish. To reinforce their effort, the men are equipped with a large hook, which they attach to the net before pulling. When a man comes ashore, he removes his hook, wades into the water, and hooks the net again. This is hard and tedious work.

A Caspian seal pops its head out of the water, but when one of the men aims at it with his gun, it immediately dives out of sight.

Every morning, the sand is criss-crossed by tracks from numerous millipeds and beetles. Ant lion larvae have constructed small pits in the sand, waiting in ambush at the bottom of the pit for an ant or another small animal to fall into the pit. As the unfortunate victim attempts to crawl out of the pit, the larva bombards it with sand, causing it to fall to the bottom of the pit, where the larva grabs it with its mandibles, whereupon it sucks out its body juices.

Corn buntings (Emberiza calandra) are singing, perched atop bushes, and from dense shrubs we hear the morse-like call of black francolins (Francolinus francolinus): “Erp-serp-se-se-serp.” Hares (Lepus) are common, and we find tracks of red fox (Vulpes vulpes) and badger (Meles meles). At dusk, golden jackals (Canis aureus) utter their eerie howling call.

One day I hear a snoring sound from a dense patch of grass. As it turns out, the noise is emitted by a sleeping wild boar (Sus scrofa), but when I approach too close, it suddenly jumps up, running for dear life. My heart almost jumps into my mouth!

From our camp, we walk across the peninsula towards Gorgan Bay, passing through fields, which are enclosed by fences of dense, spiny shrubs, constructed to keep cattle and sheep from straying. We have our difficulties finding our way through this maze. In the grass we find many species of familiar flowers, including speedwell (Veronica), shepherd’s-purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris), common storksbill (Erodium cicutarium), and scarlet pimpernel (Anagallis arvensis), the latter mostly in the pretty blue form.

We often encounter Greek tortoises (Testudo graeca), crawling about, but when we squat to have a closer look at them, they quickly retrieve their head into the carapace. If we wait a few minutes, however, the head will soon re-appear. Occasionally, a beautiful hoopoe (Upupa epops) is flushed from the grass, and when it lands land again, the large, red, black-tipped crest is invariably raised.

Finally, we reach the littoral meadows around Gorgan Bay. Many water birds are resting in its shallow waters, including white pelicans (Pelecanus onocrotalus), greater cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo), teal (Anas crecca), lesser white-fronted geese (Anser erythropus), greater flamingos (Phoenicopterus ruber), and spoonbills (Platalea leucorodia).

A young man suddenly appears out of nowhere, asking us where we are going.

“To the harbour.”

“Just a moment. I have to make a phone call!”

To whom, and why, we never learn, but in a small building near the harbour we must show our passports, before they allow us to go back the way we came. Before we proceed, we are invited to visit a cold storage plant, in which great heaps of frozen sturgeon and other fish are stored. Before stacking them, a man cuts off head and tail, using an electric saw, and these are stacked in separate heaps.

On another occasion, we give a lift to an elderly man. He informs us that he is only going 6 km. But when we have driven these 6 km, he wants to go further. We pass our campsite, and, using sign language, we inform him that we have now driven 12 km. Just 3 km more, he says. All right, we can do him that favour. After a further 3 km he still wants to continue, but by now we have had enough of him, so we stop the car and tell him to get out. He gets upset and starts shouting – what an ungrateful old bloke!

A couple of days later, I want to drive into the mountains to learn, how far spring has advanced there by now. Once again, the car gets stuck in sand, but is pulled out by a passing tractor. A short distance further on, I feel that something is wrong. One of the rear wheels has become very hot. I presume that the brake was stuck, and continue on my way. Then I hear an ominous cracking sound from the wheel, and oil starts dripping out.

Quite depressed, I walk back to our campsite. Arne, who is a mechanic by profession, joins me back to the car, and after a short examination he declares that one of the bearings has probably cracked. At a snail’s pace, we drive back to camp, and the following morning we continue to Aschur, luckily without further mishap. There is no mechanic here, so we must take the ferry across the strait to the town of Bandar Shah.

By now it is late in the day, and we stop at the roadside to spend the night here. A local boy keeps us company, singing nice songs, which we record on our tape recorder. Two soldiers approach us, but, as it turns out, they don’t intend to bother us – on the contrary, they hand us two fish as a gift!

At the repair shop, we contact the owner, a small, powerfully built man, who, as it turns out, is a fugitive from Russian Armenia. His name is Yasha, and he speaks Russian, Farsi, and Turkomani, but no English. However, that is hardly necessary to understand our problem.

Unfortunately, the damage is greater than we expected. One bearing and a cog-wheel is broken. We are told to go to the town of Gorgan, 50 km away, to get spare parts. Consequently, we board a dilapidated bus, and, as it turns out, the greatest passion of the driver is apparently racing. He drives like a madman along the tarmac road, which is full of potholes. Surprisingly, we reach Gorgan alive.

We hire a taxi to the spare part shop, and, since the taxi driver is also a madman, we arrive there within five minutes. In the shop, a clerk informs us that, unfortunately, they don’t have the required spare parts in stock – they must be ordered from far-away Tehran. The parts are quite expensive, and we cannot afford to buy all of them. We must file down the cog-wheel – and hope for a little luck. The spare parts will arrive in four or five days.

Later, we eat rice and kebab, and we start feeling quite good. When the mechanics have left for their home, we enter our car to sleep – not an easy task, as it is slanting quite a lot, one side jacked up.

We spend the following days in the company of Yasha and his staff. His friends Ali and Albert work in a bank and speak a bit of English. Even though their friend Yasha is a mechanic, their cars are old wrecks. The gear box makes ominous sounds, and the fan belt is in shreds, but such petty things are not important, as long as the car is able to move.

We make friends with the men, and they take very good care of us indeed. We eat, talk, and go on picnic trips into the mountains, bringing lunch and beer along. They also want to give us money, but, naturally, we refuse to accept it. There must be a limit!

Learning that Arne is a mechanic, Yasha wants him to become his partner in the work shop, but Arne declines.

“What will happen to my friend, if I stay here?” he says, pointing at me. Yasha looks at me for a moment and then says: “Teacher!” In his opinion, this is a suitable job for me in Bandar Shah.

Finally, the spare parts arrive, and the mechanics set to work. It is now late in the day, and Ali is of the opinion that we should have a farewell party. Albert is not able to participate. “He is afraid of his woman,” says Ali, who is unmarried. Fried fish and vodka – we are not quite sober, but, nevertheless, we manage to say that we would now like to pay for the work. Yasha blankly refuses to accept any payment – we only have to pay the spare parts!

The following morning, we’re a bit sad to leave our friends. As it turns out, after paying the spare parts, we have so little money left that we shall have to abandon our plan to go to Afghanistan. The filed-down cog-wheel still produces an ominous sound, but the arrangement seems to work, as long as we drive slowly.

Consequently, we slowly head back towards the Alborz Mountains.

Plant life in the forest has changed dramatically since our last visit. On my hikes, I find several interesting species, including hart’s-tongue fern (Asplenium scolopendrium), and Rhynchocorys elephas, a striking member of the broomrape family (Orobanchaceae), which is distributed in north-western Africa, Italy, the Balkans, Turkey, the Caucasus, and northern Iran. The Latin name is derived from three Greek words, rhunkhos (‘snout’, ‘nose’), korus (‘head’), and elephas (‘elephant’), alluding to its style, which resembles the trunk of an elephant.

One day I am out alone on a hike, when I observe what looks like a large grey dog, coming down a slope towards me. Coming to a stop, it stares at me for a moment with its yellow eyes, whereupon it turns around and disappears, at full speed. A wolf! Back at the car, I relate my experience to Arne, but he just says scornfully: ”It was just a dog!”

However, still today I insist that it was a wolf, with its yellow eyes and shy behaviour.