Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

India 1979: Hunting blackbuck with camera

The blackbuck disappeared completely from Pakistan, and from most of India. Larger herds survived only in the states of Rajasthan and Gujarat, mainly because the animals were protected by the Bishnoi. Traditionally, these people protect all wild animals, even allowing them to graze in their fields of wheat and lentils. Thanks to their protection of the blackbuck, biologists have been able to re-introduce the species to many locations in India.

My visit to a Bishnoi family is related on the page Travel episodes – India 1991: Bishnois live in harmony with nature.

Back in India, he ordered his subjects to dig canals, construct sluice gates, and build levees around an area of c. 20 km2, which was previously farmland. Small mounds were made, on which acacias and other trees were planted. Water was then led from the Gambir River into the canals to irrigate the area, thus creating a huge swamp. In this way, the Maharaja became the creator of one of the best water bird sanctuaries in Asia.

These days, at least when ample rain has fallen during the monsoon season, hundreds of painted storks (Mycteria leucocephala), Oriental darters (Anhinga melanogaster), spoonbills (Platalea leucorodia), black-headed ibises (Threskiornis melanocephalus), and several species of heron and cormorant breed in the acacia trees. Among the rarer species in the reserve, I observed Pallas’s fish-eagle (Haliaeetus leucoryphus) and black-necked stork (Ephippiorhynchus asiaticus).

In winter, the area is visited by thousands of birds, migrating here from the Himalaya and Siberia, including ducks, geese, and eagles.

A variety of mammals are also encountered, notably sambar deer (Cervus unicolor), nilgai antelope (Boselaphus tragocamelus), wild boar (Sus scrofa), smooth-coated otter (Lutrogale perspicillata), and small Asian mongoose (Herpestes javanicus). Other species are hard to observe, including blackbuck, small Indian civet (Viverricula indica), and fishing cat (Prionailurus viverrinus).

I spend many days roaming this area to photograph its rich and varied birdlife. My favourite birds are the local grey sarus cranes (Grus antigone) and the snow-white Siberian cranes (Leucogeranus leucogeranus). The latter is a winter visitor from Siberia, which was quite common in Keoladeo in former days, but has declined drastically in the later years due to poaching of the cranes, when they pass through Afghanistan and Pakistan on their migration.

[Since this text was written in 1979, Siberian crane as well as Pallas’s fish-eagle have vanished from Keoladeo, the latter due to poisoning with pesticides and heavy metals.]

“If you want to see many blackbuck, you can go to the sanctuary at Tal Chapar, in northern Rajasthan,” he informs me. “More than a thousand of them live there, and they are easy to photograph.”

He explains how to get there, which sounds fairly easy.

First, I go by bus to Ratangarh, where I intend to board another bus. Consequently, I place my backpack on the roof rack, and then approach the conductor to buy a ticket. He refers me to the ticket office, where the clerk informs me that I have to get my ticket from the conductor. I convey this piece of information to the conductor, who makes a racket and informs me that I cannot go. However, after some mumbling and grumbling, he hands me a ticket anyway.

Finally, after an exhausting ride in this bus, which is absolutely packed with people, I arrive at the village of Tal Chapar. At dusk, from my room in a tiny guest house, I hear the strange, rasping hoot of a spotted owlet (Athene brama). All night, there is also lively singing and music, supplied by tablas (small finger drums) and a harmonium.

In the morning, an employee from The Industrial Department invites me for breakfast and proceeds to interrogate me, in depth, about my job, what I am doing in Tal Chapar, my family members, their names and occupation, and much else.

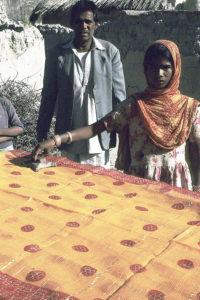

Nearby, two young girls are printing patterns on lengths of orange cotton cloth, spread out on a table. Intricate patterns have been carved into wooden blocks, which are dipped in red dye and pressed against the cloth. The process is slow, but the result is beautiful.

I take my seat in one of the hides, waiting for the blackbuck to arrive. In the other hide, an Indian photographer has taken shelter, but it seems that he doesn’t possess the necessary patience to photograph wildlife. When a small herd of blackbuck approaches the waterhole, he immediately runs out to get close-up photos – only managing to scare the animals away. Exasperated, I give up and leave my hide. The nearby plains are dotted with blackbuck. Mr. Singh didn’t exaggerate – there must be at least a thousand of them.

In the village reservoir, many herons, ducks, and coot (Fulica atra) are feeding, while common mynas (Acridotheres tristis), ring-necked parakeets, doves, and many other birds arrive to drink. A small Asian mongoose zooms along the shore, and a large, black snake disappears into a bush. A beautiful hoopoe (Upupa epops) is feeding in a grassy area, while peacock (Pavo cristatus) strut about, resembling decorated noblemen. From far away, the distinct call of grey francolins (Francolinus pondicerianus) can be heard: “Ji-de-li-de-li-ji-de-li-ji-de-li!”

In the evening, a group of men gather in my room. A pipe of tobacco is handed around, and one of the men starts singing, again accompanied by tablas and harmonium. Occasionally, the other men join in as a chorus. Their singing continues for hours. I learn that they are giving a farewell party to one of the men, who has been transferred to a place far into the desert, near the Pakistani border.

“Sir, do you have a written permission from my superior, the District Forest Officer in Bikaner, to enter the reserve?”

“No, I’m sorry, Mr. Singh didn’t inform me that I would need one.”

“In that case, unfortunately, we cannot allow you to enter the reserve!”

“But yesterday your staff told me that it wouldn’t be a problem for me to get the permission!”

“I’m sorry, but we cannot give you permission to enter without a written permission from the D.F.O. You must go to Bikaner to get the permission. Then you can return here and get our permission to enter.”

“But Bikaner is far away, and I already spent a long time getting here. Can’t you make an exception and give me permission?”

All my arguments are in vain, but finally he agrees that a phone call from his boss will be sufficient to allow him to let me enter the sanctuary. This day, however, is a Sunday, and the post office is closed, but, nevertheless, the friendly postmaster opens the office and allows me to use the phone. This phone would be a treasure for any technical museum in Europe. Nothing but whirring and wheezing can be heard, and I fail to get any connection. Then the kind postmaster gives it a try. He manages to get a line through to the D.F.O.’s office, only to learn that he is absent. I ought to have told myself – after all, it is a Sunday.

I make a quick decision. I’ll to go to the water reservoir and from there sneak into the reserve to some waterholes, where the antelope often drink. These waterholes are situated near the outskirts of the sanctuary, so I convince myself that this action must be rather harmless. I run back to the guesthouse, grab my equipment and manage to arrive at the waterholes without being seen by the staff.

Three females and two beautiful bucks with enormous, spiralled horns approach the waterhole to quench their thirst, not far from the bush, behind which I’m hiding. The bucks walk a short distance, spar a bit, and then re-join their herd. Several other blackbuck also approach the waterhole, and, gradually, my mood changes to the better. I have seen these beautiful animals at close quarters, and managed to get fine pictures.

While waiting for a third bus in Sikar, I am bothered by beggars, shoe-shiners, and snot-nosed kids. The queue in front of the ticket office is unusually long, but luckily the conductor from the previous bus spots me and drags me in front of the queue.

This act is indeed very nice of him, but, alas, of very little use, because when our bus finally arrives, it’s already packed with passengers. This fact doesn’t seem to subdue anyone – they push and shove and shout, and when the bus leaves the station, there must be about 150 passengers, inside, on the roof, and in every other place a person can possibly cling to.

Inside the bus, an obese man offers me his seat, my protests being to no avail. That’s Indians for you! The most paradoxical people in the world. For two hours, I am seated in a most inconvenient position, before the crowds thin out a bit.

Arriving in Jaipur, I’m captured by one of the usual obnoxious rickshaw boys. When I ask him to take me to a hotel, he says: “Yes-yes, I know a good hotel!” He then proceeds to drive me 200 m to a hotel, which he finds good – namely the one, where he gets commission for every guest that he brings there.

I’m too exhausted to protest, but when he demands 2 Rupees to drive me the short distance, I feel an almost irresistible urge to kick his behind.