Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Borneo 1975: Canoe trip with Punan tribals

Our hotel is utilized by the prostitutes and their customers, and throughout the night there is great activity, people entering and leaving the rooms. We sleep in a large dormitory, and some of the other guests seem to find it interesting to watch the activities of the couples through peepholes, which have been carved between the boards in the wall.

From Sibu, we board another freight boat to Kapit. The river is now much narrower, with dense rainforest along the shores in many places. Collared kingfishers (Todiramphus chloris) take off from trees, and a striated heron (Butorides striata) crosses the river in front of the boat. On board, we see our first tribals, with pierced earlobes and lots of tatoos on their breast, back, and legs. The indigenous population of Borneo is comprised of many tribes, including Iban, Punan, Kayan, Kelabit, and Penan, known by the common name of Dayaks.

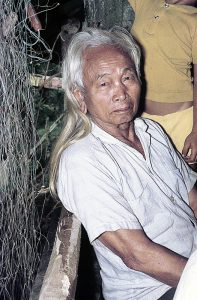

To go to Belaga, still further upriver, we have to board an expensive express boat. Belaga is the last village on the river, which can be visited by tourists. To visit areas close to the border with Kalimantan, you need a special permit, which is very difficult to obtain. The river is now quite narrow, and often we encounter protruding rocks, surrounded by dangerous rapids. Two Kayans board the boat, old men with gentle and calm eyes, long hair, and gold rings in their long earlobes. Obviously, they have enjoyed a lot of tuak (rice wine), making them quite merry.

Belaga is a small village, consisting of a boat landing, a bazaar – a modified Dayak longhouse – the district office, a police station, a school, and a number of dwellings. Several Western tourists are visiting Belaga, and we are allowed to spend the night in a house, belonging to the Evangelist Mission, whose priest is a friendly Kayan tribal.

We all pay a visit to the only restaurant in the village, owned by a Chinese, who takes great advantage of his monopoly, as a very small portion of nasi goreng (fried rice with vegetables) costs one Malaysian Dollar (app. 70 US Cents). This is outrageous, so we start arguing about the price – after finishing our meal. The owner just smiles, refusing to receive any payment. We can go! When we are hungry again, we have no other choice than to go back to the restaurant, where the Chinese is not at all surprised to see us. He merely serves our meal and receives his payment of one Dollar per head – no arguing this time!

The water level at Long Ba is quite low, so I have to wade barefoot through a lot of mud before reaching firm ground. A couple of boys receive me and guide me to the village longhouse. Here I meet Ida Nicolaisen, who has been living here on and off for a couple of years, and by now speaks the Punan language fluently. She receives me very courteously and takes me to the tuai rumah, the village chief, in whose house I can stay.

Usually, a Dayak village consists of only one house, a longhouse, which is in fact an entire community under one roof. A longhouse is mainly constructed from tabelian wood, which is very hard and durable. Most longhouses are app. 75 m long and 25 m wide, and – at least in former days – always situated near a river, providing easy access to drinking water.

Closest to the river is a common veranda, stretching along the entire length of the longhouse. Many activities take place here. Men and women sit in groups, often separated by sex, performing a number of tasks, including basket weaving, cleaning of rice, and production of hunting spears. Next to the veranda, each individual family has a separate apartment, where several generations live together. Behind the apartments, another veranda is used for drying rice, pepper and other crops, and for hanging up laundry. On the other side of this veranda are the kitchens.

A longhouse is erected on poles, and to enter it you must balance up a log, into which steps have been cut. Often there is no rail, and the first couple of times you wonder, whether you’ll make it without falling down. There are several reasons, why longhouses are constructed on poles. For one, it keeps the number of dangerous creatures, like snakes and scorpions, entering the house, at a minimum. Floors consist of thin poles, tied together, and when you sweep the floor, dust and rubbish fall through the cracks between the poles. Chickens and pigs roam beneath the house, eating any edibles.

The most important reason, however, lies in the past. Before c. 1900, most Dayaks were headhunters, and a man’s status depended on his ability to kill enemies and cut off their heads as trophies. The heads were brought back to the longhouse and stored under the roof. Before a young man could marry his fiancée, he had to bring her a freshly cut head. By constructing their house on poles, the inhabitants could haul up the ‘ladders’ in the evening, making it more difficult for enemies to enter the longhouse at night.

The British, who colonized Sarawak in the 1800s, forbade headhunting, and the punishment for breaking this law was severe. Around 1900, headhunting had almost vanished. But the Dayaks had not entirely lost their desire to hunt heads, and during World War II, the British again allowed them to cut off heads – but only heads of Japanese soldiers, no others. The Dayaks immediately began head hunting, and thousands of Japanese soldiers lost their lives.

Even though headhunting does not exist today, most Dayaks still prefer the traditional way of house construction. A large number, however, now live near the cities to work in oil palm plantations, which are replacing the rainforests of Sarawak at an alarming rate these years.

In former times, Dayaks placed their deceased relatives on top of high burial poles, which were decorated with carved faces and snake patterns. Today, deceased Dayaks are buried.

Dayak men spend most of their time hunting and fishing. They punt up small rivers to roam the forest, accompanied by their hunting dogs, in search of deer, monkeys, bearded pigs, turtles, or other animals. If they happen to kill a mother, they bring back the young to the longhouse, where the children will take care of them, until they are big enough to be eaten.

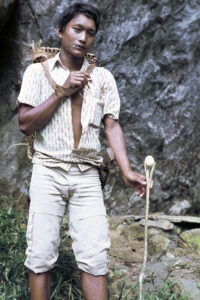

In former times, the Dayaks used blowpipes, up to 2 m long, for hunting. Inside the tube they placed plant marrow, which would fit the pipe exactly. Into the marrow they stuck a very sharp arrow, 15 to 18 cm long. The point of the arrow was smeared in a brown mass, containing strychnine, obtained from fruits in the forest. When a Dayak blew into his pipe, the arrow would shoot out with a tremendous force, piercing the bark of a tree at a distance of up to 20 m. He would be able to hit prey up to 40 m away, and when an animal was hit, the poison would soon take effect. Even if the animal managed to climb to the top of a tree, the poison would cause its muscles to relax, and it would fall to the ground. Today, there are almost no blowpipes left in Borneo.

The women fetch water for the household in the river, but laundry is done on the bank. The kids have invented an amusing game. Stark naked, they throw mud on each other, afterwards sliding on their behind down the smooth surface of the mud, ending in the water with a splash. The adults don’t interfere. Their upbringing of children is very liberal, but nevertheless the kids are nice and friendly, willingly performing any task their parents may demand from them.

Punans love cock fighting, and almost every man is breeding fighting cocks. A sharp metal spur is tied onto the cock’s own spur, whereupon the competing men release the two cocks. Before the fight, the gathered men make bets, as to which cock will win. When their favourite cock attacks its opponent, they shout and cheer. The fight that I watch is short and bloody. The cocks are a blur of wings and legs, and they disappear behind some bushes. The cock belonging to the Chinese trader lies dead, intestines hanging out. The Punans are overjoyed.

In the evening, people sit in small groups, talking, or girls perform the old-time dances, with fans of hornbill feathers attached to their wrists, moving gracefully to the rhythm of the music. In former times, the music was performed by men, playing drums and a local, two- or three-stringed instrument, called a sapé. Today, however, the Punans have become modern, and the music is delivered by a small cassette tape recorder.

When a person is ill, a ceremony is performed, the purpose of which is to call upon the good spirits to expel the bad spirit, which has entered the sick person. Ida and I participate in a healing ceremony, in which a sick man is going to be cured for ‘insanity’. However, Ida is of the opinion that the man just wants some attention. He has been living a very quiet life and feels a bit like an outcast.

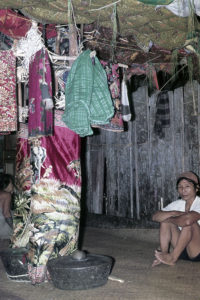

A scaffold, with a burning candle on its top, has been decorated with brightly coloured bits of cloth. The shaman, the sick man, and several women now circumambulate the scaffold, while three girls are beating drums of various sizes.

The shaman is wearing a special headgear, with numerous hornbill feathers attached. Suddenly he and the sick man jump towards the spectators, uttering a piercing ‘psit’. This sound, as well as the burning candle, attracts beneficial spirits, who supposedly will chase out the evil spirit.

When the beneficial spirits have entered the sick person’s body, the shaman touches his face with both hands, making a sucking sound to extract the evil spirit. A sword is rubbed on his body, arms and legs, while a very old woman is beating the dancers on head and back several times with an inflorescence from the betel palm (Areca catechu).

At one point during the ceremony, the shaman’s sarong drops to the floor, but he ignores this, continuing to dance, clad only in his underwear. Someone hands him his sarong, but he goes on fooling around, touching several persons with the edge of the cloth, gasping ‘ladylike’. When they reach out to touch the cloth he gets ‘scared’, jumping backwards. Now the old lady, carrying another inflorescence from the betel palm, walks around to all spectators, beating them on their shoulder. During the ceremony, food was served for the spirits, but since they didn’t eat it, we all consume it, washing it down with strong and sweet rice wine.

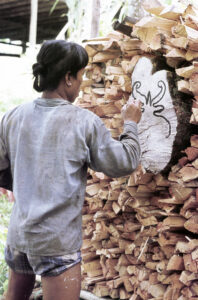

Two men, who have chopped a lot of firewood, now stack it and decorate it with various mythological images. This firewood is meant to be used to cook food for a ceremony, which is going to take place several weeks later, commemorating the villagers who have died during the last year or so. The food is for the deceased.

Now the Punans partake in a small preliminary ceremony. Rice with vegetables and dried fish is served, with a glass of rice wine. After the meal, a man approaches me, pouring rice into my hair and down my neck. This is the part for the deceased! A young girl throws vegetables on a young man, and the whole affair soon develops into a mock fight.

The following morning, we say goodbye to Ida and commence our journey up the Ba River in two canoes, perahus, each paddled by two men. A fourth Punan has agreed to join us without pay, as he is going into the forest to collect rattan stems. We make good progress, soon reaching the first rapid. The men paddle furiously against the strong current, ligaments on their strong arms taut. They now stand up, punting the canoes through the rapids, safely and securely. On several occasions, we must leave the canoes, waiting on rocks in the river, while the men pull the canoes over the rocks.

We encounter several such rapids, but otherwise the river is calm and quiet, the only sounds coming from birds and insects in the forest, and the splashing of the paddles. In open areas it is very hot, but where the rainforest is dense it is wonderfully cool in the shade, with beautiful beams of sunlight penetrating the foliage.

Our first night is spent in a simple hut, constructed of branches, the roof consisting of several layers of palm leaves. Tables and beds are scaffolds, made from thin branches. Five or six men from Long Ba are already gathered in the hut. They now light a fire and cook rice which we eat with newly caught, fried fish. Dusk is approaching, and a huge chorus of insects make a tremendous racket. However, we are very tired and soon fall asleep on the scaffolds.

After breakfast the following morning – again rice and fish – we continue our journey upriver. As we are out of rice, the Punans go ashore at a small hut, where they take some of the stored rice, placing money in a can to show that the rice has been bought – not stolen. However, theft is almost unknown in this area.

One of our guides borrows a fishing net to be able to catch our daily supply of fish, a throwing net with a string attached to the centre. The man holds on to this string while throwing the net, which spreads out like a fan on the surface of the water. Small iron rings, which are attached to the edge of the net, pull it downwards, thus trapping any fish that might happen to be beneath the net.

The man has brought some stones with him, and now he throws one of these ahead of the canoe. This seems to attract fish. When we get to the point, where the stone splashed into the water, he throws the net with a secure hand. This is repeated several times. On most occasions, a fish or two are caught, and the man jumps headlong into the river to extract them from the net. The total catch is ten fish, enough for us for two days.

Because of our fishing activities, we don’t travel far this day, and stop for the night at another small hut along the shore. A large turtle, which is swimming in the river, is taken ashore, and to prevent it from escaping, the man drills a small hole at the edge of its carapace with his spear, then tie it to a pole with a piece of rattan stem. Thus, it will remain here, until the men return.

During the night, one of the men manages to catch a jungle rat. In the morning, it is roasted over the fire and served for breakfast. It was quite tasty!

Most of the day we wade through streams or walk along muddy paths. I wouldn’t call them paths, as I am not able to distinguish them from the surrounding forest, but our guides lead the way, quickly and safely. Where dense vegetation is taking over the ‘path’, our guides cut it down with parangs, large jungle knives.

Late in the afternoon, we reach a small, dilapidated hut near a crystal-clear brook. On our way, our companions have collected a large number of leaves from a certain palm species, and now they proceed to ‘tie’ them together, sticking sharp strips of rattan stems through them. When the work is done, the leaf-mats are placed over gaping holes in the roof. Rotten branches on the sleeping scaffold are replaced with fresh ones, and now we have nice sleeping quarters – quickly and efficiently. On our way, we also picked a lot of edible fungi from a rotten tree trunk, and these we now enjoy with rice and fish.

The following morning, we climb a low mountain – hard work indeed in the intense heat and humidity, but we are rewarded with a splendid view over the forest-clad hills around us. Arriving at the peak, we make a brief stop beneath a couple of huge rocks, which are covered in dense, soft, green moss. From cracks in the rocks, we detect the distinct smell of ammonium, emitted by guano from bats, which roost in the cracks during daylight.

We consume the rest of our food, leaving an egg for the spirits, before we start our descent. It is steeper than the ascent, and we often have to cling to the climbers that cover the rocks. At the foot of the mountain is Sungei Puti, a clear and cool brook. Past the brook, our guides lose the trail, and for some time we have to make our way through dense vegetation, cutting down plants that block the way. A prolonged shower leaves us drenched, but we’re soon dry again in the intense heat.

The rice has just been harvested, the bare, yellow stems standing out among a dense tangle of green weeds. At the other end of the field, men and women are threshing the harvest by trampling it with their bare feet.

After a brief rest we continue towards the village, about an hour’s walk away. The path is muddy and slippery after the rain shower, sometimes leading through abandoned rice fields. Every second year, the villagers must clear a new patch of forest to grow rice, as the nutrients are soon washed out of the soil.

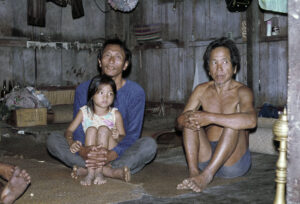

The village is tiny, consisting of only two or three small houses, built on poles. We are invited into one of them and spend the evening with its inhabitants. A young man entertains us by playing on a sapé. A couple of men agree to take us downriver, to the Kakus River, in a perahu, provided with an outboard engine.

In the afternoon, we arrive at a small sleeping hut, and our companions persuade us to stay here, as there are no huts further down the river. As it turns out, this is a wise decision. During the night it rains heavily, and in the morning the water level has risen significantly, making it possible for us to use the outboard engine.

Soon we reach the Kakus River, where we observe a small saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus). In the old days, there were large and dangerous crocodiles in Borneo, but most of them have long since been shot. We spend the night in an Iban village, where we are entertained by a boy who plays the sapé, while another boy performs a dance to the music. In a nearby field, people are conserving a bark roll by applying smoke to it. These rolls are for storing harvested rice.

The following morning we get a lift with a Chinese to the small town of Tatau. And exactly one week after leaving Long Ba, we reach Bintulu.