Hinduism

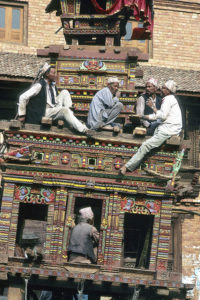

Morning fog, enveloping Hindu temples on Durbar Square, Bhaktapur, Nepal, evaporates at sunrise. This city is mainly inhabited by Newars, a people of mixed Indo-European and Mongolian origin. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

At dawn, this Brahmin greets the rising sun and the sacred Ganges River, Varanasi, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Women, carrying offerings to a Hindu temple in Ubud, Bali, Indonesia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

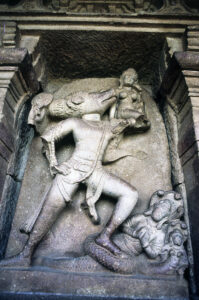

This splendid piece of art from Changu Narayan, Kathmandu Valley, Nepal, shows Garuda, half man, half eagle, who is the mount of the supreme god Vishnu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Praying Hindu pilgrims, Pura Ulun Danu Bratan Temple, Lake Bratan, Bali, Indonesia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The word Hindu is of Persian origin, meaning ’people from the Indus’. Nowadays, however, it refers to followers of Hinduism as a religion. Unlike other world religions, Hinduism has no founder, but is rooted in the Vedas (from the Sanskrit vid: to know) – a collection of doctrines, which arose among the Aryans, a Middle East tribe, who invaded the Indus Valley around 1500 B.C.

The Vedas were learned by heart by Brahmins (scholars, or ‘priests’), and were passed on orally from generation to generation, until they were written down around 1800 A.D. The Vedas relate Aryan gods and myths, and among the Aryans, ritual offerings were the main essence.

Gods and myths from the local Dravidian religion in the Indus Valley were incorporated into the Aryan religion, and Hinduism is the result of this amalgamation.

Hinduism also differs from other world religions in that it does not instruct its followers to pray to specific gods, or to perform specific rituals. The spiritual universe is interpreted from the Vedas, and also to some degree from the great epics Mahabharata and Ramayana.

There is a huge difference in the way that a philosopher and a farmer will interpret and perform his religion, and Hinduism is so capacious that the business man of today can also find a meaning in it. For the major part of Hindus, their religious belief and the daily life are intertwined to an extent, that Hinduism is best described as a way of life as well as a religion.

The Aryan invaders were pale-skinned, whereas the local Dravidian inhabitants, whom the Aryans made their slaves, were dark-skinned. People were divided into four castes, in Sanskrit varna, which merely means ‘colour’ – in all probability referring to the various skin colours of the Indus Valley population. According to one Veda text, this classification of people was dictated by the gods.

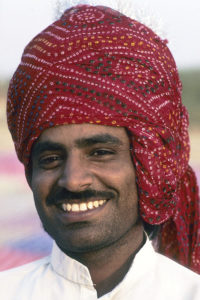

This turban-clad dancer in Bikaner, Rajasthan, is of Aryan descent. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Tamil girl in Tarangambadi, Tamil Nadu, is of Dravidian descent. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Hindu caste system

Hindu rites, including presentation of offerings to the gods, are performed by the Brahmins, who interpret the Vedas, and often live strictly according to these doctrines.

Originally, the Brahmins made rules for the righteous way of life for the four castes. Naturally, they placed themselves in the uppermost caste, Brahman, claiming that they originated from the mouth of the god Brahma, the creator of the Universe (see caption Hindu deities). Today, not all Brahmins are scholars, but include persons from other trades, including farmers.

The second caste, Kshatriya (in Nepal called Chhetri), were said to originate from Brahma’s arms. Traditionally, members of this caste were warriors, whose duties included protecting the country against invaders. In today’s society, they often occupy high posts in the armed forces and in the police, or as government officials, but the caste also includes traders and others.

The third caste, Vaishya, include farmers, artisans, traders, and others. They were said to originate from Brahma’s thighs.

These three higher castes are classified as dvija (‘twice-born’). Across their body, from the left shoulder to the right hip, many men of these castes wear a sacred string (janai), consisting of three twined threads. The string of Brahmins is made of cotton, the one of Kshatriyas of hemp, and the one of Vaishyas of wool. (More about janai is related in the caption Hindu festivals below.)

The fourth caste, Shudra, typically including labourers and servants, were said to originate from Brahma’s feet.

Over time, these four basic castes have been split into thousands of sub-castes, called jati, often based on the various branches of trade. Most Hindus marry within their caste, or even sub-caste, and it is your duty to observe its rules, morals, and rituals. These duties are called dharma (not to be confused with the Buddhist dharma).

Outside the caste system are dalit – ‘the untouchables’, or, as they are termed by the Indian government, ‘the scheduled caste’. They perform ’unclean’ work, such as refuse disposal and dealing with dead people or animals, including cremation and leather work. In principle, all non-Hindus are dalit, including Christians, Muslims, Indian tribal peoples, and tourists.

Meditating Brahmin at the Ganges River, Varanasi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

While waiting to perform rituals for pilgrims at the Ganges River, this Brahmin is reading a newspaper. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Brahmins, giving advice to pilgrims, Manakamana Temple, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Swayambhunath is a huge Buddhist stupa in Kathmandu, Nepal. Around this stupa, various Hindu temples are also found, reflecting the religious tolerance of the inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley.

Swayambhunath and other stupas are described on the page Religion: Buddhism.

Near Swayambhunath, this Brahmin is performing an offering ceremony outside a temple, dedicated to the Hindu goddess of children’s diseases, Harati, also called Ajima. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

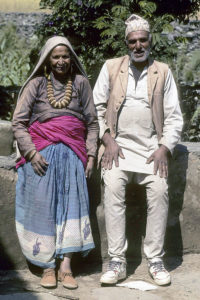

Not all Brahmins are scholars, and this caste also takes in persons from other trades, including farmers, like this elderly couple in the Kabeli Valley, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A mountainous area north of Kathmandu, central Nepal, holds 54 lakes, all of which are sacred to Hindus. Every year, during Full Moon in July or August, thousands of devout pilgrims undertake the demanding hike to these lakes to have a cleansing bath in their icy waters. Orthodox Hindus wish to bathe in all 54 lakes. The lakes are described in depth on the page Countries and places: Sacred lakes of Shiva.

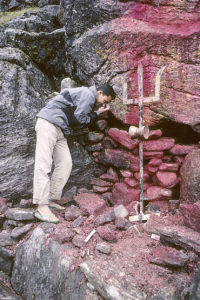

Ganga Thapa, a young pilgrim of the Chhetri caste, applies a tika mark on his forehead, taking the vermilion dye from a small Shiva shrine at the Gosainkund Lake. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hindu temples

Hindu temples, clustered around a sacred lake, Pushkar, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Temples, dedicated to the supreme god Brahma, are only seen a few places. This one is situated in the town of Pushkar, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Manakamana Mandir (in Nepali meaning ‘the temple that grants wishes of its devotees’) is dedicated to the goddess Bhagwati, an incarnation of Devi (see caption Hindu deities: Shiva and Devi). It is situated on the Kafakdada Hill at an elevation of 1,300 m in the Gorkha District, central Nepal, at the confluence of the Trisuli and Marsyangdi Rivers. A village has sprung up around the temple, which receives hundreds of thousands of visitors a year. A cable car, built in 1998, leads up to the temple.

The temple is in two storeys, built in the traditional Nepalese pagoda style. According to Nepalese legend, it dates back to the 17th Century, during the reign of the kings of Gorkha.

The temple began to lean after the 1934 earthquake, whereas the 2015 earthquake made cracks on the roof and made the temple tilt even worse. It has since been restored.

The Manakamana Temple. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tiny sculptures, depicting goddess Bhagwati, Manakamana Temple. They have become red due to offerings of red dye. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A gopura, or gopuram, is an entrance tower, leading into a Hindu temple or temple complex. The pictures below show a gopura in the Minakshi Temple, Madurai, Tamil Nadu, which is adorned with thousands of sculptures, depicting deities and myths. This temple is dedicated to goddess Minakshi, a South Indian name for Shiva’s shakti (see Hindu deities below), who, in northern India, is known by various names, including Devi, Uma, and Parvati.

(Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

According to legend, the moon god Chandra was the progenitor of the rulers of the Chandella Empire, situated in present-day Khajuraho, Madhya Pradesh.

Once, in moonshine, a beautiful woman, Hemavsti, was bathing in Lake Rati, when Chandra descended from the sky and embraced her. Later, she gave birth to a son, who became the first ruler of the Chandella lineage.

Between 900 and 1050 A.D., 85 stone temples were erected in Khajuraho, whose friezes and sculptures depict many aspects of life in those days. Numerous sculptures show women in challenging positions, their hips and breasts accentuated. They possibly depict apsaras, supernatural female beings, who are superb in the art of dancing. They are often depicted dancing to music, delivered by Gandharvas, court musicians of the rain god Indra. They entertain and sometimes seduce gods and men. Other sculptures depict mithuna, couples in intercourse.

This sculpture in the Vishvanath Temple, Khajuraho, depicts a mating couple, which seems to embarrass the two spectators. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Khmer relief, depicting dancing apsaras, Bayon, Angkor Thom, Cambodia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This sculpture in the Vishvanath Temple, Khajuraho, depicts a voluptuous woman, possibly an apsara. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Another sculpture, depicting a beautiful woman, possibly also an apsara, Ta Prohm, Angkor, Cambodia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This frieze in the temple Jagdish, from 1651, in Udaipur, Rajasthan, may also depict apsaras. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Khmer relief at Angkor Wat may also depict apsaras. The darker colour on their breasts stems from greasy hands of numerous visitors! (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

According to the Mahabharata, Bhima, one of the Pandava brothers (see caption Hindu deities: Krishna), spent some time in exile in Manali, Himachal Pradesh. During his stay, he fell in love with a local beauty, Hadimba (also called Hidimbi), who, as a young woman, had vowed to marry the man, who was able to defeat her brother Hadimb (or Hidimb) – a very brave and strong person.

Bhima managed to kill Hadimb, and, as she had vowed, Hadimba married him. Later, the local people regarded her as a goddess, an incarnation of the supreme Mother Goddess Devi.

The Hadimba Temple in Manali was erected in 1553 over a cave in a huge rock, where Hadimba supposedly meditated. Later, this rock was worshipped as an image of the deity.

The Hadimba Temple is adorned with horns of various animals, including bharal (Pseudois nayaur), and antlers of Kashmir stag (Cervus hanglu). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hindu deities

Many Westerners believe that Hinduism holds thousands of gods, but, in reality, they are merely aspects of one supreme deity. These many gods, which often have several names, simply reflect the countless aspects of the human mind.

Originally, only male gods existed in the Aryan pantheon, but at an early stage, the female aspects, or energies, of these gods, called shakti, became an important part of worship. In daily use, this shakti is personified, becoming the ’wife’ of the deity in question.

Worship of gods, called puja, takes place through prayer and offering at statues or images of the gods, which are found everywhere in streets, temples, and private homes.

Below, the most important deities of the Hindu pantheon are presented.

Brahma and Saraswati

Brahma, the creator of the Universe, has four heads, often with a full beard, and several arms. He is often depicted on his mount, a goose, or standing on a lotus flower. Worship of this deity only takes place on a small scale, probably because his deed is over and done with, and praying to him would hardly benefit you. Temples dedicated to Brahma are few and far between. One is found in the town of Pushkar, Rajasthan.

Saraswati is Brahma’s shakti (female aspect). She is depicted with four arms, often sitting on her mount, a swan. She is the goddess of learning, wisdom, and music, mostly worshipped by students. Many homes have pictures of her, in which she is playing on her string instrument, the veena.

Khmer relief, depicting Brahma, riding on his mount, a goose, Banteay Srei, Angkor, Cambodia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Khmer rock carving in the Stung Kbal Spean riverbed, Cambodia, depicts the reclining Brahma. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sculpture, depicting Saraswati, playing on her veena, Indeshwor Mahadev Temple, Panauti, Kathmandu Valley. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Fire in the Khandava Forest

Once Agni, the god of fire, suffered from indigestion and went to Brahma for help. Brahma told him that his only cure was to consume the entire vegetation and inhabitants of the Khandava Forest.

Agni now approached Krishna and Arjuna (one of the Pandava brothers) to ask for their help in his stupendous task, to which they readily agreed. Their task was to prevent any of the inhabitants of the forest from escaping the fire.

Now Agni set fire to the forest, which soon burned with an immense force. The water in ponds and lakes began boiling, killing all creatures. Birds that tried to escape were pierced by Arjuna’s arrows.

The rain god Indra, who was the protector of the forest, began pelting the forest with showers, which, however, dried up in mid-air due to the intense heat.

This Khmer relief in Banteay Srei, Angkor, Cambodia, depicts horror-striken animals and people during the fire in the Khandava Forest. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Riding on his 3-headed elephant Airavata, Indra creates showers in his effort to extinguish the fire. – Banteay Srei. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Vishnu and Lakshmi

According to legend, at the beginnings of time, the supreme god Vishnu was resting in the primeval sea, lying on a huge serpent, the 7-headed cobra Shesha. When he awoke, Vishnu had assumed the shape of a golden egg, from whose shells the Sky and the Earth were created. It is said that when the World comes to an end, he will assume a similar position and recreate the World.

Vishnu is usually depicted with four arms, sitting, lying, or standing on a lotus flower, or on Shesha. He holds a conch in one of his hands, pointing it towards the sea, where all creation began.

Vishnu represents the positive and preserving aspects, protecting humans and gods against demons and other evil forces. For this reason, he has assumed nine other forms, so-called avatars. According to Hindu mythology, the tenth avatar, Kalki – a white horse with the head of a goat – will soon emerge on Earth, bringing an end to it due to Man’s excessive desire for material goods. A picture of our time?

During religious festivals, or when on a pilgrimage, worshippers of Vishnu, called Vaishnavites, adorn their face with a white figure, shaped like a tuning fork, running from their forehead down the nose.

Lakshmi, Vishnu’s shakti, is the goddess of wealth, happiness, and beauty. She is often depicted on a lotus flower, or holding a lotus in her hand. Lakshmi is the most important deity during Dipavali, or Tihar (popularly called ’Festival of Lamps’). In the evening, during this festival, countless small oil lamps illuminate streets and houses, and long rows of lamps lead to the entrance of houses, so that Lakshmi can find her way to the family cash box and fill it up.

The mount of Vishnu and Lakshmi is Garuda, part eagle, part human, who is often guarding the entrance to Vishnu temples.

This brass water tap in Tusha Hiti, a royal bath from 1646 in the Old Royal Palace, Durbar Square, Patan, Kathmandu Valley, Nepal, depicts Vishnu and Lakshmi, riding on Garuda. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

During the festival of Tihar, Lakshmi visits all her devotees. In the evening, countless small oil lamps illuminate streets and houses. – Kathmandu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this sculpture from Patan, Kathmandu Valley, Garuda is depicted with an eagle’s head and a human torso. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These Khmer sculptures on the outer wall of Preah Khan (top), and on the Terrace of Elephants, both at Angkor, Cambodia, also depict Garuda with an eagle’s head and a human torso. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The sculpture in the picture below, 6 m long and carved from one huge rock, is called The Reclining Vishnu. He is depicted, reclining in The Cosmic Ocean, resting on a somewhat unusual bed – the 11-headed cobra Anantha Naga. This remarkable sculpture is found in a temple in the village of Budhanilkantha, in Kathmandu Valley.

During the festival Haribondhi Ekadasi, the face of The Reclining Vishnu is being cleaned ritually with milk. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kurma, 2nd avatar

In the legend The Churning of the Milk Ocean, from the Bhagavata-Purana, it is related that the gods had become weakened and had been usurped by the asuras (demons).

The gods appealed to the supreme god Vishnu for help, and he suggested that they should regain their power by drinking the miraculous amrita, the nectar of immortality, which they could obtain by churning the cosmic milk ocean, thus bringing the jar with amrita to the surface.

However, Vishnu advised the other gods to treat the asuras diplomatically by suggesting them to jointly churn the ocean. When the amrita was brought to the surface, Vishnu would ensure that the gods got hold of it.

The asuras readily agreed to participate in the churning. To perform this stupendous task, the gods and the asuras uprooted the mountain Mandara, placed it upside down in the ocean, and coiled the giant, many-headed naga (serpent) Vasuki around it. By pulling alternately at each end of Vasuki, the mountain would act as a gigantic churn, thus bringing the amrita to the surface.

The mountain, however, began sinking into the ocean floor, causing Vishnu to assume the shape of a giant, named Kurma, half man, half turtle. He then dove to the bottom of the sea, where he placed Mandara on his back, thus preventing the mountain from sinking.

Finally, the jar with amrita surfaced, whereupon a fierce battle between the gods and the asuras ensued, the latter grabbing the jar and running away with it.

Again, the gods appealed to Vishnu, who assumed the form of a new avatar, Mohini, a beautiful goddess, who seduced the asuras and managed to get hold of the jar of amrita, thus preventing evil from becoming eternal, and preserving the good.

This relief in the wall above the entrance to an old well, Raniji-ki-Baori, in Bundi, Rajasthan, depicts Vishnu as his second avatar, Kurma. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Due to the role of Kurma in the legend The Churning of the Milk Ocean, turtles are sacred to Hindus. This sculpture, overgrown by green algae, was encountered in a temple in Ubud, Bali, Indonesia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this frieze at Angkor Wat, Cambodia, Hanuman, the monkey god, is urging the gods to pull harder on the body of Vasuki. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Part of a long line of sculptures at Angkor Thom, Cambodia, depicting asuras, holding on to Vasuki. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Varaha, 3rd avatar

Once, when an asura (demon) named Hiranyaksha had dragged the Earth, personified as the goddess Bhudevi, to the bottom of the cosmic ocean, Vishnu assumed the shape of a gigantic boar, named Varaha. He and the asura fought for a thousand years, before he managed to kill the demon. He then retrieved the Earth from the ocean, lifting it on his tusks, and restored Bhudevi to her place in the universe.

This sculpture in the great temple of Aihole, Karnataka, depicts Vishnu as Varaha, trampling the demon Hiranyaksha, and lifting Bhudevi on his shoulder. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rama, 7th avatar

Rama is often depicted with blue skin. According to the great epic Ramayana, he was a crown prince, but, in a moment of thoughtlessness, his father promised one of his other wives that her son should inherit the throne for 14 years, and during this period, Rama should be expelled from the kingdom.

Rama knew of no higher law than to obey his father, and he spent his exile wandering about in the forests with his chosen one, Sita, and his half-brother, Lakshmana.

One day, Sita was abducted by Ravana, a 10-headed and 20-armed demon king from Sri Lanka. Hanuman, leader of the monkey army, which supported Rama, went to Sri Lanka to negotiate Sita’s release, but Ravana’s soldiers tied a rag, soaked in oil, to his tail and set fire to it. This was noticed by the god of fire, Agni, who protected Hanuman from the heat, while the flaming tail, in retaliation, set many houses on fire. An enormous leap brought Hanuman back to India.

During the final battle, Rama managed to kill the evil demon, and Sita was released. When the 14 years of exile had passed, Rama went home and assumed his throne.

The Balinese Keçak Dance (‘Monkey Dance’) depicts a scene from Ramayana. Rama’s fiancée Sita has been abducted to Sri Lanka by the demon king Ravana, and Hanuman’s monkey army is trying to rescue her. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Khmer relief in Banteay Srei, Angkor, Cambodia, depicts another scene from Ramayana. The monkey brothers Sugriva and Valin battle for the crown, while Rama fires an arrow at Valin, killing him. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hanuman – the monkey god

As a reward for his services, Hanuman was made a deity. He inspires strength in people, making him popular among men, while women regard him with mistrust, because he is unmarried. During puja, Hanuman statues are smeared in orange sindur, consisting of cinnabar or another red dye, mixed with mustard oil.

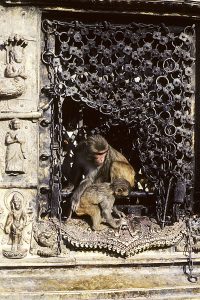

Due to the great deeds, performed by the monkey army in the Ramayana, monkeys are considered sacred, and troops of rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta), bonnet macaques (M. radiata), or grey langurs (Semnopithecus) often live around temples, where part of their diet is rice, sweets, or other edible offerings.

Sculpture, depicting Hanuman, Kathmandu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This sculpture, depicting Hanuman, is adorned with flower offerings, Ubud, Bali, Indonesia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sculpture at the Kalika Temple in Gorkha, Nepal, depicting Hanuman. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Over the years, the features of this Hanuman sculpture at the Pashupatinath Temple, Kathmandu, have become blurred, due to a thick layer of orange sindur (red powder, mixed with mustard oil), applied by devout Hindus. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A female rhesus monkey and her young, feeding on rice grain, presented as offerings at the Swayambhunath Stupa, Kathmandu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Krishna – 8th avatar

Krishna is a very popular deity, identified by his blue skin. He is often depicted playing on his flute, accompanied by his greatest love, Radha, or with gopis, beautiful female herders, whom he was fond of seducing.

Krishna grew up with a herdsman, well protected against a cruel king, Kansa, who was killing male children, as a fortune teller had warned him that he would be overthrown by a young man. However, a divine voice warned Krishna, who took shelter with the herdsman. When he had reached manhood, he killed the evil king and liberated the people.

Krishna is one of the main characters in the great epic Mahabharata, which describes a conflict over the throne between the five Pandava brothers and their cousins. In a passage of the Mahabharata, the Bhagavad Gita (’The Sublime Song’), Krishna is the charioteer of one of the Pandava princes, Arjuna, trying to convince the prince that he must fight for honour and power, even against relatives.

This carving in a window opening in the city of Puri, Odisha (Orissa), depicts Krishna in a local black form, named Jagannath, with his brother and sister. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Khmer relief in Banteay Srei, Angkor, Cambodia, depicting Krishna, killing the evil King Kamsa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Shiva and Devi

Shiva is a complex deity, destroying and re-creating in an eternal interaction. He is sometimes depicted in the three-headed form, Trimurti, which represents his three aspects: the destructive, the preserving, and the mild and feminine (shakti).

He is often depicted performing a savage dance, his four arms flailing in dynamic positions. His hair is tied in a knot, which is also seen among many of his followers, called Shaivites. A third eye on his forehead is able to behold what is hidden for humans. His forehead is adorned with three horizontal lines – a pattern, which his followers also use. In one of his hands, he carries a trisul (trident).

Shiva is also connected with cremation platforms, where he dashes about, smeared in ashes. For this reason, Shaivites often smear themselves in ashes and dust.

Shiva’s mount is a great bull, Nandi. Sculptures, depicting this bull, is often placed in front of Shiva temples as a guardian.

Shiva’s shakti is known by various names, including Devi (the Great Mother Goddess), Durga, Parvati, Sati, Uma, and Kali. In the form Durga, she is often depicted riding on a tiger or a lion.

A lingam is a phallus-shaped stone, representing Shiva as the fertility god. Such lingams are often placed on a yoni, a carved, flat stone, which resembles a stylized vagina, representing Devi. Such sculptures, called linga-yonis, which symbolize the unification of Shiva and Devi, are often placed outside Shiva temples.

On the island Elephanta, Mumbai, is a splendid statue, depicting Shiva in the form Trimurti. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lichen-covered sculpture in a temple in Ubud, Bali, Indonesia, depicting Shiva and his mount Nandi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Khmer relief from Banteay Srei, Angkor, Cambodia, shows the god of love, Kama, firing an arrow at Shiva to make him more attentative to his wife Parvati. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Old man at a lingam, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Four-headed lingam, observed outside a temple in Parphing, Kathmandu Valley. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This exquisite marble sculpture in Pushkar, Rajasthan, depicts a four-headed Shiva, Devi, and Nandi, worshipping a linga-yoni. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Linga-yoni, Budhanilkantha, Kathmandu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lingam, linga-yoni, and Shiva’s trisul (trident), Amritsar, Punjab. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In Hindu mythology, Mahishasura was a powerful demon, who threatened to usurp the gods, and not even the mighty Vishnu and Shiva could resist him.

Now Durga went into action. Riding on her lion, she attacked Mahishasura, who changed into a huge buffalo, then into a lion. Durga sliced off his head, but he then changed into an elephant, whereupon Durga cut off his trunk. In spite of the demon hurling large mountains at the goddess, she managed to kill him with her spear.

This sculpture in the great temple at Aihole, Karnataka, depicts Durga, riding on her lion, battling against Mahishasura, in the shape of a buffalo. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

During the festival of Dassera, or Durga Puja, which celebrates Durga’s victory over Mahishasura, a procession with musicians is marching through the streets of Kullu, Himachal Pradesh. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In Deshnok, Rajasthan, a local goddess, Karna Mata, is regarded as an incarnation of Devi. Her followers believe that if you are reborn as a rat, you escape the wrath of Yama, ruler of the underworld and the god of judgement after death. For this reason, rats are sacred.

In the Karna Mata Mandir Temple in Deshnok, pilgrims feed a horde of black rats (Rattus rattus). (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Khmer relief depicts Yama, seated on his mount, a water buffalo, Angkor Wat, Cambodia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kali

Bluish-black Kali is a bloodthirsty form of Devi. She is often depicted with a bloody sword in one of her many hands, and the chopped-off head of a demon in another. Her tongue is blood-red, hanging far out of her mouth, her necklace and belt consist of chopped-off heads, and chopped-off arms are tied around her hips.

In temples dedicated to Kali, a daily offering of blood is made. In former days, certain Kali sects sacrificed humans, but today billygoats and roosters are the most common offerings. Kali worship mainly takes place in West Bengal, and the capital of this state, Kolkata, formerly called Kalikata, is named after this goddess.

Sculpture, depicting Kali with a malla (garland) of marigolds, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Newar people, waiting in line with their offerings at a Kali temple, Dakshinkali, in the Kathmandu Valley. The goat has just left pellets on the feet of a woman. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In the Dakshinkali Temple, ritual slaughtering of sacrificial animals is carried out by people of a certain caste. Note the cut-off heads of roosters. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ganesh

This deity, traditionally regarded as the youngest son of Shiva and Parvati, has a human body, but the head of an elephant. He is often depicted with his four arms raised in a friendly gesture, while standing on his mount – a rat. He is a very popular deity, and before making important decisions it is wise to place a malla (flower garland) on an image of Ganesh, while saying a prayer.

There are various legends as to how Ganesh got his elephant-head. According to one, it happened in this way:

One day, when Shiva was away on a longer journey, Parvati wished to take a bath. She created a young man from clay to guard outside the house, while she was having her bath, ordering him not to let anybody enter the house.

Shortly after, Shiva returned from his journey, and the young man told him not to enter the house, as he was ordered. This made the fierce-tempered god so furious that he chopped off the young man’s head. However, this deed made Parvati so angry that she threatened to destroy the universe, unless Shiva restored the young man’s head to his body. Sadly, his head had been destroyed, so Shiva ordered a servant to go outside the house and take the head of the first one he would meet. This happened to be an elephant, and the servant – taking his master’s order literally – ordered the elephant to hand over his head.

This Ganesh sculpture in Ubud, Bali, Indonesia, is adorned with mallas (garlands), made from marigold flowers. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ganesh sculpture with offerings of red dye and flower petals, Kathmandu, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This house wall in Jaisalmer, Rajasthan, is decorated with a painting, depicting Ganesh and his mount, a rat. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This malla has been presented as an offering outside a shrine on the Asan Tole Square, Kathmandu, dedicated to Ganesh. Very appropriately, an albinistic black rat (Rattus rattus) is sitting behind the lattice! (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Surya

Surya is the Hindu sun god, from the Sanskrit surya (‘sun’). He has many other names, including Aditya, Bhanu, and Savitr. In the Mahabharata, he is called ‘the eye of the universe, the soul of all existence, the origin of all life’. Surya is often depicted, holding a chakra (disc). He is revered in a number of festivals, including Pongal (see Hindu festivals below). The worship of Surya declined greatly around the 13th Century, perhaps as a result of the Muslim conquest of north India.

Surya, riding in his chariot with his charioteer and two of his wives. – Carving in the temple Indreswor Mahadev Mandir, from 1291, Panauti, near Kathmandu, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sculpture in the Sun Temple, Konark, Odisha (Orissa), depicting Surya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Life without desire – moksha

In the West, most people understand time as a straight line, moving from the past, via the present towards the future. As opposed to this perception, Hinduism operates with a cyclic conception of time, envisaging the course of life as a wheel: You are born, grow up, and die, whereupon you are reborn in a different body. This process is called reincarnation, and devout Hindus claim that all living beings undergo this cycle.

All Hindus hope for a better life in their next reincarnation. Whether you are reborn as an animal or a human, rich or poor, is determined by your karma – a result of your deeds in your former life. Broadly speaking, karma is a reckoning of your good and evil deeds. If you have performed more good than evil, you are reborn in a higher caste, and if you have done more evil than good, you are reborn in a lower caste, as a dalit, or as an animal.

The final goal of an orthodox Hindu, however, is to completely avoid being reborn, obtaining moksha – a state, in which you have no wishes or desires (corresponding to the nirvana of Buddhism). The best way to obtain moksha is through ritual offerings, and through recognition without ulterior motives.

This man brings an offering to a statue of Kalo Bhairab, Durbar Square, Kathmandu. This deity is the local version of Shiva among the Newar people of the Kathmandu Valley. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This woman is burning incense as an offering to Krishna in the Sri Venkatesvara Temple, Tirumalai, Andhra Pradesh. Venkatesvara is a local name of Krishna in this state. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Offerings, consisting of various herbs and mallas (flower garlands), have been draped around this statue of Ganesh in the Sri Minakshi Temple, Madurai, Tamil Nadu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Worship of the Ganges

Numerous rituals are performed on the shores of the Ganga River (Ganges), the most sacred river to Hindus. The following pictures show scenes from this river in the most sacred of cities, Varanasi.

Pilgrims, cleansing themselves ritually in the Ganga. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This woman scoops up water from the sacred Ganga into her cupped hands, then presents it as an offering back into the river. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Aarthi is a ceremony, performed at sunrise or sunset, in which incense is presented as an offering to Mother Ganga. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tiny oil lamps and marigold flowers are placed on ‘rafts’, made from leaves, which are then presented as an offering to the Ganga. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mallas, flower garlands, which have been presented as an offering to the Ganga, are floating on the surface. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

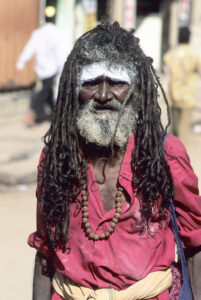

Sadhus

These holy men wander about, carrying very few basic possessions, making a living from alms. Many of these sadhus strictly follow the Hindu doctrines, and their only goal in life is to obtain moksha.

Carrying his few belongings, this sadhu is walking down a road in Kolkata, West Bengal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

I met this colourful sadhu in the great Minakshi Temple in Madurai, Tamil Nadu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

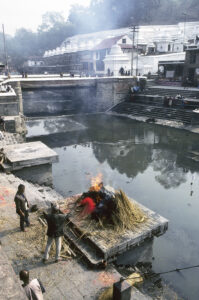

Cremation

Almost all deceased Hindus are cremated. For the sake of the next reincarnation of the deceased, his or her relatives make a great effort to carry out the cremation rituals in a proper way. The oldest son, who is tonsured, ignites the funeral pyre. To increase the chances of the deceased obtaining moksha, the ashes are strewn into a sacred river, preferably the mighty Mother Ganga, or one of her tributaries.

In Kathmandu, most cremations take place along the sacred Bagmati River, a tributary to the Ganga. Prior to the cremation, many rituals are performed by the relatives, including throwing rice and dyes on the deceased. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The body is placed on a platform on the river bank, then covered in straw and wood, which is ignited. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A family member throws red dye on the deceased. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A certain caste of men see to it that the cremation is carried out properly. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cremation, taking place at night, Bagmati River. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hinduism in Southeast Asia

The spreading of Hindu religion and culture to Southeast Asia began in the first millennium B.C., partly through traders, who settled there, partly through conquests.

Hinduism had an enormous influence on the civilizations of Southeast Asia. Brahmins probably travelled with Indian merchants, and many were patronized by rulers who converted to Hinduism, hereby giving rise to numerous Hindu empires in Indochina, the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Java, Bali, and parts of the Philippine archipelago.

Over the years, in most of these former Hindu kingdoms, Hinduism was replaced by Islam or Buddhism. Hinduism is still the major religion on Bali, but in most other places, only minor Hindu communities exist today, mainly descendants of Indian settlers, especially Tamils.

Prambanan is a Shiva temple, 40 m high, near Yogyakarta, Java, Indonesia, which was erected in the 9th century A.D., during the reign of a Saivite king of Mataram. This temple is part of a complex, comprising 242 temples, which was rediscovered in the 1880s. It was restored in 1953. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This algae-covered sculpture in the Wenara Wana Temple (popularly called ‘Monkey Forest’), near Ubud, Bali, Indonesia, depicts Rangda, a Hindu demon queen with lolling tongue and pendulous breasts. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Khmer Empire

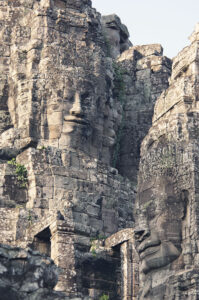

Notable among the Southeast Asian Hindu kingdoms was the Khmer Empire, which left a superb legacy in the form of the Angkor Wat ruins, in present-day Cambodia. In the 19th century, when European travelers visited these ruins, they were overgrown by rainforest. Since then, most of the vegetation has been removed, with the exception of Ta Prohm, which has been preserved in the state it was found.

At Angkor Thom, countless large stone blocks have been carved and fitted together to form numerous huge faces, depicting Lokesvara, a great Hindu Khmer king. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This picture from Ta Prohm shows a ruin, overgrown by a huge rainforest tree of the species Tetrameles nudiflora. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hindu festivals

Maha Shivaratri

Several days before the important festival Maha Shivaratri (‘Great Shiva’s Night’) is celebrated, numerous Shaivites (followers of Shiva) gather at the Pashupatinath Temple in Kathmandu, often considered the most important Shiva temple in the world. Many of these Shaivites smoke charas (hashish) to enter a different mental level and thus get in contact with their god.

These Shaivites at the Pashupatinath Temple, smeared in ashes and wearing nothing but a loincloth and rosaries, are smoking hashish. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The following 4 pictures show a procession in the city of Jaipur, Rajasthan, celebrating Maha Shivaratri.

Decorated chariot with a huge image, depicting Shiva. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This decorated chariot shows Shiva, riding on his bull Nandi with his consort Devi (also known as Parvati, Durga, or Uma). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Adorned elephants. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These men perform as Krishna (with blue skin) and an unknown god, aiming at each other with bow and arrow. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Janai Purnima

Janai is the sacred hand-spun string, which men from the three highest Hindu castes wear around their body, from the left shoulder to the right hip. During Janai Purnima, on Full Moon Day in July or August, every Tagadhari (‘wearer of the sacred string’) will replace his janai with a new one.

For Vaishnavites (followers of Vishnu), the Muktinath Temple in Mustang, central Nepal, is an especially auspicious place to change your janai. During Janai Purnima, thousands of pilgrims are crowding around this temple.

These girls are cleansing themselves ritually, passing under 108 fountains, which bring forth water to the temple from the sacred Muktinath spring. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The 108 fountains at the Muktinath Temple are shaped as ox heads, with the exception of three, which depict mythic creatures. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pilgrim, igniting oil lamps during Janai Purnima, Muktinath. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Holi

This spring festival celebrates the god Krishna, and the victory of good over evil – a gay festival, in which people, regardless of caste, pelt each other with red, yellow, purple, or green powder, or with water, dyed with powder. For this reason, Holi has been dubbed The Festival of Colours.

My ‘colourful’ adventures during this festival is related on the page Travel episodes – India 1991: Attending Hindu festivals in Rajasthan.

During Holi, family members perform a stick dance around the grandparents, while dyed powder and rice is thrown into the air. – Jaisalmer, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In Charbhuja, Rajasthan, where these pictures were taken, Holi lasts no less than 15 days. The lower picture shows a young man, throwing red powder on women, who are leaving a temple. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bisket Jatra

Around the Hindu New Year, this festival is celebrated with vigor by the Newar population in the cities of Bhaktapur and Thimi, Kathmandu Valley.

Bisket means ‘serpent killer’. According to legend, a king of Bhaktapur had but one daughter, who had a mighty appetite on lovers. Every night, she wanted a new one, and, mysteriously, he was always found dead in the bed in the morning. Many families mourned their lost sons.

A young prince, visiting the town, heard about the misery. He offered to take over the role as lover, bringing his sword to the bedroom of the princess. When she had fallen asleep, he kept awake. He observed two thin threads, coming out of the nostrils of the princess, transforming into two monstrous serpents. They attacked the prince who killed them with his sword.

In the morning, when the king’s servants came to remove the dead prince, they saw him, to their surprise, sitting calmly on the bed, talking to the princess. The dead serpents were tied to a tall pole, which was erected on one of the town squares. The prince now married the princess, and the king announced that the event should be celebrated every year.

He ordered a tall chariot to be built, housing a statue of the goddess Bhadra Kali, so that she might also have a look at the dead serpents. Bhadra Kali is the female aspect of Kalo Bhairab, the name of Shiva among the Newars of the Kathmandu Valley. Later, an even larger chariot was built to house Kalo Bhairab. The prow was high and curved, symblosing the serpent god. A small brass face of the betala, Kalo Bhairab’s servant, was tied to the prow.

Nowadays, some days before the New Year, Kalo Bhairab and Bhadra Kali are placed in their heavy chariots, which are pulled to the square Taumadi Tole by many men, using strong ropes. The chariots are painted and adorned, and the betala image is tied to the tall prow. During these preparations, people bring offerings to the chariots.

On New Year’s Day, a lot of boys climb the chariot of Kalo Bhairab, which is heaved to a steep road, leading down to Khalna Tole, nær the Hanumante River. On each side of the road is a drainage canal, into which the wheels of the chariot fit. Now the men push and pull the wheels of the chariot into these canals. Slowly, the wheels start turning, the entire chariot is swaying, and suddenly it disappears down the road, full speed. At the end of the road is a sandy area, where the chariot comes to a stop. Now the smaller chariot of Bhadra Kali goes through a similar process.

On Khalna Tole lies a 20 m tall pole, to which two banners, symbolizing the dead serpents, are tied. Now this pole has to be erected – a dangerous task. It has sometimes fallen, killing several people, which is regarded as a bad omen for the coming year.

Thousands of people arrive to bring offerings to Kalo Bhairab and Bhadra Kali – roosters, whose blood is smeared onto the betala, and also rice, flowers, sacred water, and money. Men gather to play music, and people march in processions to temples near the raised pole and along the river.

In the afternoon, the pole is taken down again – yet another dangerous task. Two teams of men pull from either side, competing to be the team to topple the pole. When the pole is swaying, people scatter in all directions. Finally, it falls with a huge crash, symbolizing that the previous year has come to an end, and with that the two evil serpents.

During Bisket Jatra, numerous men haul a chariot, containing an image of Kalo Bhairab, through the streets of Bhaktapur. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These men have just sacrificed goats to Kalo Bhairab. They apply rice kernels, red powder, and mustard oil to the severed heads, whereupon the oil is ignited. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This picture shows the tall pole with two banners, symbolizing the evil monster serpents. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A rooster has been sacrificed, and the blood is smeared onto the betala, which is tied to the prow of Kalo Bhairab’s chariot. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pongal

This festival, also called Sankranti, takes place in South India, celebrating the outset of the harvest. During this festival, cows are washed and decorated with turmeric powder, their horns and hooves are painted, and they are fed with pongal (a mixture of rice, sugar, lentils, and milk).

Decorating a cow during Pongal, Mysore, Karnataka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Thaipusam

This festival, which celebrates Shiva’s and Devi’s son Subramaniam (‘The Virtuous One’), takes place in the Batu Caves, near Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. During this festival, pilgrims undergo various self-inflicted pains to repent their sins, or to have their wish fulfilled.

The festival is described in detail on the page Travel episodes – Malaysia 1985: Thaipusam – a Hindu festival.

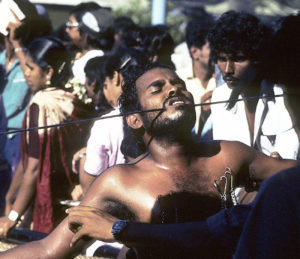

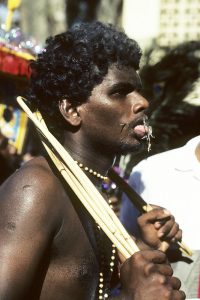

During Thaipusam, a pilgrim has pierced his cheeks with a spear (top), while another has stuck numerous small needles into his tongue. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Uploaded May 2017)

(Latest update September 2023)