Buddhism

Buddhist pagodas in morning mist, Bagan, Myanmar. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

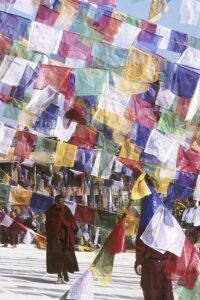

Tibetan Buddhist prayer flags, torn and entangled by the wind, flutter on a rocky ridge beneath King Tashi Namgyal’s old fort, built in the 1500s, near Leh, Ladakh. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Honouring The Buddha, red candles have been ignited beneath the Shwedagon Pagoda, Yangon, Myanmar. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

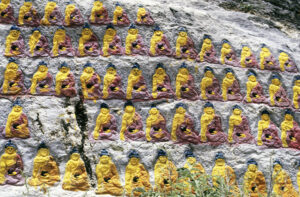

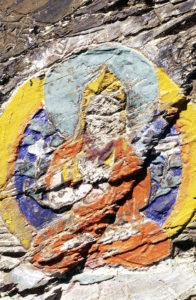

Meditating Buddhas, painted on a rock along the Lingkhor kora, an 8 km long pilgrim route around Lhasa, Tibet, which today, sadly, has been largely destroyed by Chinese building construction. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

One day, around 2,500 years ago, a man, about 35 years old, was hiking along a dusty road near the present-day town of Gaya, Bihar, northern India. For five years, he had been travelling the length and breadth of northern India, trying to get an answer to a question, which had bothered him for a long time: Why did people suffer so much?

The man’s name was Siddharta Gautama. Tradition has it that he was born c. 566 B.C., but recent research suggests that it was maybe around 490 B.C. He was born into a noble family, as his father was a Raja (prince) of the Sakya clan, ruling near the modern town of Lumbini, southern Nepal.

Legend has it that on the night of his conception, Siddharta’s mother, Queen Maya, dreamed that an elephant had placed a lotus flower in her womb.

This relief from Borobodur, a Buddhist temple from the 8th century A.D., at Yogyakarta, Java, Indonesia, depicts Queen Maya with the elephant of her dream. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Because of the role of the elephant in Queen Maya’s dream, it is often depicted in Buddhist artwork. These pictures show a frieze in a wall, surrounding the giant stupa of the Buddhist temple Ruvanvalisaya Dagoba, Anuradhapura (top), and a stela at the stupa Kantaka Chetiya, Mihintale, both Sri Lanka. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Suffering humans

Siddharta lived an easy and carefree life within the enclosures of the palace, until he was about 29 years old. Then, during a visit to a nearby town, he noticed four things, which affected him deeply. First, he met a poor old man, which showed him, how miserable life could be. Next, he observed a very sick man being carried to a doctor, which showed him the frailty of humans, and physical pain. Later, he saw a corpse being carried to the river bank to be burned, which showed him that everyone has to die. And finally, he met a sadhu (holy man), who was begging for food. He owned nothing, but exuded peace and wisdom. This demonstrated the emptiness of possessing material things to Siddharta.

His observations made him speculate upon the reasons for human suffering. He felt that his life as a rich man’s son was without substance, and he left the palace to seek out Brahmins and wise men, who had spent a long time in meditation. However, none of them could give him a satisfactory answer. He therefore decided to leave his family to live an ascetic life and try to find an answer to his question through meditation. For five years, he walked from one village to the next, but his search did not help him to get an answer.

Outside Gaya, Siddharta sat down in the shade of a large pipal tree, determined not to move before he had found a satisfactory answer to his quest. For 49 days, he was seated beneath the tree, in deep meditation. Then he arose, convinced that he had found the answer, and that he was able to recognize the coherence of life.

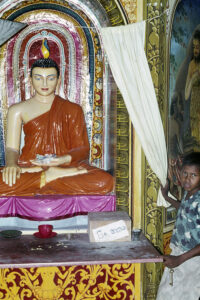

This image in a temple in Hikkaduwa, Sri Lanka, depicts the meditating Buddha. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This relief, carved on a pillar in Sri Dalada Maligawa (‘Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic’), Kandy, Sri Lanka, depicts the meditating Buddha. According to legend, this temple houses a canine tooth of The Buddha. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wall painting, depicting a scene from the life of the Buddha, Atanagalle Temple, western Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This sculpture at Gal Vihara, Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka, 14 m long, depicts the Reclining Buddha. To the left a standing Buddha, 7 m tall, which was formerly believed to be his disciple, Ananda. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Absence of desire

Siddharta maintained that everything in life is connected, as links in a chain, which can only be broken by knowledge. He defined The Four Truths, which explain people’s sufferings and frustrations. They can briefly be described as follows:

Human life is unhappy, because it has numerous sufferings. These sufferings emerge because of needs, wishes, and desires, and the attraction of material things is nothing but an illusion of the senses. Unhappiness, ultimately, is caused by egoism, which can be avoided by following these five rules of conduct: not to kill, not to act immorally, not to lie, not to steal, and not to take drugs.

From this day, Siddharta walked about, giving lectures to people about his new philosophy. In the course of time, he was followed by a growing crowd of people, who were fascinated by these new thoughts. These followers called him The Buddha (‘The Enlightened One’).

The Buddha emphasized that he did not get his thoughts from any god, but that he was an ordinary man who had been able to develop a method to avoid suffering. He only passed on his thoughts verbally, and he would adjust his teachings according to his audience. He did not try to persuade people to abandon Hinduism, and he didn’t deny the existence of gods. He merely explained that the final goal in Buddhism is to recognize that the ego is an illusion, and to realize that it is the cause of all suffering.

If you attain this knowledge, you have broken the endless cycle of rebirths. This complete enlightenment is called nirvana (best translated as ’absence of desire’) – a condition of perfect harmony, in which the ego has been eliminated, causing all desire to have ceased and thus no longer being able to disturb this knowledge. These are the basics of Buddhist dharma (teachings).

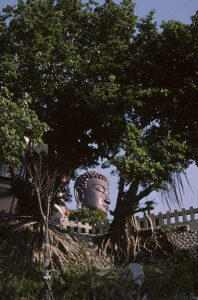

Siddharta’s followers called him The Buddha (‘The Enlightened One’). These pictures show a huge Buddha statue near Changhua, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Karma

Devout Buddhists believe that their karma (the sum of their good and bad deeds in the present life) affects your position in the next life. By doing many good deeds you will have a better chance of reaching a higher position after rebirth.

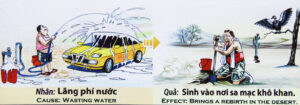

These drawings, depicted in the Tran Quoc pagoda, Hanoi, Vietnam, vividly illustrate the reults of doing bad deeds. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bodhi tree and lotus

To followers of The Buddha, the pipal tree, beneath which Siddharta attained nirvana, was called the Bodhi tree (‘tree of enlightenment’). When this species was described scientifically by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus in 1753, he named it Ficus religiosa (‘sacred fig tree’). It is presented in depth on the page Plants: Fig trees.

Over time, the Bodhi tree became a pilgrimage site for devout Buddhists, and a town named Bodhgaya arose, housing numerous temples.

The lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) is a plant that often grows in murky water, but produces a wonderful flower, fresh and clean, above the water. The Buddha is often likened to a lotus flower, indicating his purity in a polluted human world. As the waterlily (Nymphaea) grows in similar places and produces flowers, which superficially resemble lotus flowers, this plant is also sacred to Buddhists. Botanically, however, the two plants are not closely related.

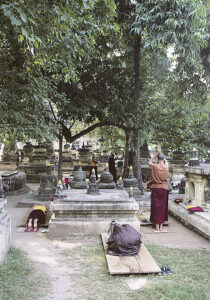

Buddhist monks meditate and prostrate in front of a sacred Bodhi tree in Bodhgaya – an offspring of the ancient tree, beneath which Siddharta Gautama attained nirvana. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sinhalese woman, meditating beneath a sacred Bodhi tree at a temple in Kalutara, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The lotus plant produces wonderful flowers. This one was observed near Siem Reap, Cambodia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Offerings of fresh waterlily flowers have been placed beneath a Buddha statue in Bodhgaya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

State religion during Emperor Ashoka’s reign

In 326 B.C., when Alexander the Great had conquered most of the Indus Valley, he was stopped east of the river by Chandragupta Maurya’s army. Maurya assumed control in parts of northern India, creating a dynasty, which was named after him.

During his reign, Gandhara art and architecture blossomed, including pillared temples. Maurya’s successors conquered nearby principalities, and the dynasty reached its peak during the reign of Emperor Ashoka (272-238 B.C.), comprising the Indus and Ganges Valleys, and parts of central India.

Ashoka fought aggressive wars to expand his empire. In 263 B.C., he won a battle against a local Kalinga king, near the town of Bhubaneswar, in what is today the state of Odisha (Orissa). It is said that the water in the Daya River turned red from the blood of fallen soldiers. According to legend, Ashoka was so chocked by this bloodbath that he stopped all further expansion campaigns.

He now converted to the non-violent Buddhism, which was made state religion in his empire. Numerous Buddha statues and stupas were constructed. Originally, stupas were tombs for rulers, heroes, or holy men. According to legend, The Buddha wished that his ashes be placed inside a stupa.

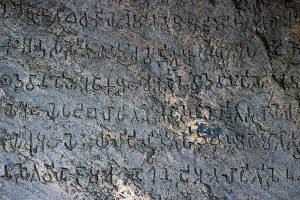

Ashoka also ordered quotes from The Buddha´s teachings to be carved into rocks, so that wayfarers could learn from them. Missionaries were sent to the neighbouring countries, including Sri Lanka, Tibet, China, and Myanmar.

As a commemoration of Ashoka’s conversion to Buddhism, the Japanese, constructed a Peace Pagoda, the Shanti Stupa, in 1969-72, on a hilltop near the Daya River, where the emperor’s last battle took place.

Buddhism was the dominant religion in India until about 800 A.D., when Hinduism regained its former influence through aggressive missionary work, implemented by the Brahmins, who probably felt that their power was crumbling.

Today, Buddhism is of minor importance in India, but it is still the dominant religion in Sri Lanka, Indochina, Tibet, Mongolia, China, Taiwan, and Japan.

Daya River, Odisha (Orissa), seen from the Shanti Stupa, a Japanese Peace Pagoda, which was erected on a hill named Dhauligiri. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Emperor Ashoka ordered quotes from The Buddha´s teachings to be carved into rocks in the Pali language, so that wayfarers could read them. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

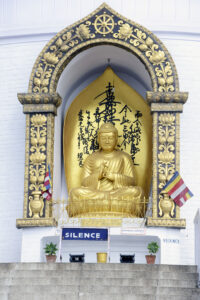

Another Japanese Peace Pagoda has been erected near Pokhara, Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dharma wheel

The circular shape of the Buddhist dharma wheel represents the perfection of the dharma, the teachings of the Buddha. The rim represents concentration during meditation, while the hub represents moral discipline. At the centre is a Daoist yin-yang symbol, where yin represents the dark, or negative forces, and yang the bright, or positive forces, the two being intertwined, symbolizing that they are interconnected. The deer, kneeling beside the dharma wheel, symbolize the deer garden at Sarnath, where Siddharta gave his first lessons.

Buddhist dharma wheel on the Jokhang Temple, Lhasa, Tibet (see below). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Meditating Buddhas

Sculptures, depicting meditating Buddhas, the so-called Dhyani Buddhas, do not symbolize living persons like Siddharta Gautama, but are merely images which show five meditation postures.

According to legend, these Dhyani Buddhas arose from the brilliant light, emitted by a thousand-leaved lotus flower in the Kathmandu Valley. This light contained five differently coloured rays, one for each of the five Dhyani Buddhas.

Four of these meditating Buddhas are often depicted as a sculpture, a so-called chaitya, in which they are seated back to back, their faces turned towards the four cardinal directions – always the same for each of the four Buddhas. They may also be identified by colour, tool, female aspect, or position of their hands.

Akshobhya is facing east, pointing palm and thumb of his right hand inwards. He is touching the earth, to make it a witness of his ability to resist the temptations, which the evil goddess Mara is imposing on him to disturb his meditation. He is a symbol of the highest truth.

Ratnasambhava, facing south, holds the palm of his right hand forward – a symbol that all knowledge is equal.

Facing west is Amitabha, with his hands folded in his lap, palms facing up. He symbolizes the ability to distinguish knowledge.

Amoghasiddhi, facing north, stretches the fingers of his right hand out, as a blessing. He is the symbol of perfect wisdom.

The fifth meditating Buddha, Vairocana, is rarely seen on chaityas, as he is the central figure, thus not having a specific cardinal direction. On pictures, he is depicted above the others. He is teaching, seated with his hands folded across his chest – a symbol of absolute knowledge.

This chaitya at the Swayambhunath Stupa, Kathmandu, Nepal, shows four of the meditating Buddhas. It is adorned with an offering, a Chinese hibiscus (Hibiscus rosa-sinensis). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This sculpture at Gal Vihara, Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka, depicts a meditating Buddha. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stone sculptures, depicting meditating Buddhas, amid fallen leaves, Ubud, Bali, Indonesia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rock paintings, depicting meditating Buddhas, on the pilgrim route around Lhasa, Tibet, called a kora (see caption ‘Mahayana Buddhism’ below). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This sculpture in the Wat Pho Temple, Bangkok, Thailand, depicts a meditating Buddha, adorned with offerings of marigold and lotus flowers. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Theravada – the Old Buddhist School

An important issue of Buddhism is to preach that all things are connected. Man’s energy is a part of the energy of the Universe, and to increase your knowledge about these energies, thereby changing your mental level, you can meditate, or you can recite powerful words, mantras.

The ultimate goal is nirvana, but only the selected few are able to reach this goal. Most people must be reborn again and again, and in which shape, this is going to take place, depends on the number of good or bad deeds you have done in your lifetime. You can easily be reborn as an animal, so it is quite natural that to Buddhists, killing is a great sin.

In the course of time, various schools of Buddhism have evolved, interpreting The Buddha’s teachings in different ways. The Theravada Buddhism is the Old School, which teaches followers to meditate individually, hereby seeking the path toward nirvana. This school is predominant in Sri Lanka and Indochina.

Prasat Phra Dhepbidorn (‘Royal Pantheon’), in English called Grand Palace, a Theravada temple in Bangkok, Thailand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Golden Reclining Buddha, Wat Pho Temple, Bangkok. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Theravada monks, Pitipana, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Small Theravada shrine, Van Long Nature Reserve, Vietnam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rays from the rising sun illuminate a Buddhist pagoda, built atop a limestone crag in Yangshuo, Guangxi Province, China. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This huge statue depicts ‘The Spectacled Buddha’, Shwedaung, central Myanmar. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lanka Tilaka, Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka, was built during the reign of King Parakramabahu (1153-1186). The building is made from reddish bricks, and the outer walls are covered with images and carvings, hence its popular name ‘The Image House’. It houses a Buddha statue, also made from bricks, which was previously about 12 m high. However, today the head is missing.

Nearby lies a stupa, which was originally named Rupavathi. Today it is greyish, but in former times it was snow-white, hence its other name Kiri Vihara (‘milk white shrine’). It was likewise built during the reign of King Parakramabahu, presumably dedicated to his wife Subhadra.

Lanka Tilaka and Kiri Vihara, Polonnaruwa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

As an offering, this girl applies leaf gold to a Buddha image, Grand Palace, Bangkok, Thailand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Woman, praying at Buddha statues, with much applied leaf gold and offerings of marigold flowers, Wat Pho, Bangkok. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Elephant tusks adorn the entrance to the sanctum sanctorum of Sri Dalada Maligawa (‘Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic’), Kandy, Sri Lanka. According to legend, this temple houses a canine tooth of The Buddha. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Decoration on the ceiling, Sri Dalada Maligawa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Monks on their morning begging round, Nyaung Shwe, Lake Inle, Myanmar. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stupa in evening light, Kalutara, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

An ancient Theravada shrine on this rocky islet in Van Long Nature Reserve, Vietnam, has crumbled and is now being restored – obviously a difficult task. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

During a ceremony, in which a boy is being initiated as a Buddhist monk, members of his family are photographed together with two orange-clad monks, Wat Benchamabophit (‘Marble Temple’), Bangkok. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mirisavatiya Dagoba, an ancient Buddhist stupa from 2nd Century B.C., Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Street altar, Bangkok, Thailand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A huge area around Bagan, Myanmar, is dotted with the remains of c. 2,200 ruined Theravada pagodas and temples. During the height of the Bagan Kingdom, between the 11th and 13th Centuries, more than 10,000 temples, pagodas, and monasteries were built in this area.

Buddhist pagodas in morning light, Bagan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Shwedagon – a Theravada pagoda

Shwedagon is an enormous Buddhist pagoda in Yangon, the capital of Myanmar. Especially in the evening, many local Buddhists come to this shrine to pray, give offerings, or participate in cleaning the pagoda.

In the evening, the gigantic Shwedagon Pagoda is illuminated. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Little boy in prayer. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flower offering for The Buddha. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

People, pouring water on a sacred sculpture, depicting a rat, beneath a Buddha statue. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Volunteers, sweeping the platform in front of the pagoda. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Evening sunlight on the platform. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mahayana Buddhism (Lamaism)

In the 600s, when Buddhist monks began preaching their faith in Tibet and Mongolia, the local populations soon embraced these new thoughts. Prior to the introduction of Buddhism, the local religion was an animistic belief, called Bon, whose followers were convinced that all things in nature – animals, rocks, trees, etc. – contained a spirit, good or evil, and that these spirits could control the actions of humans. The Bon belief is described in depth on the page Religion: Animism.

Inevitably, the new religion, called Mahayana Buddhism or Lamaism, contained many elements from Bon. Today, this religion dominates in Tibet, Mongolia, Nepal, Ladakh, Sikkim, and Bhutan.

Mahayana emphasizes the concept of Bodhisattva – a Buddhist who is on the threshold of nirvana, but instead of entering this ultimate state, chooses to use his knowledge to guide other persons towards the same goal. Thus, Mahayana Buddhism emphasizes solidarity and collectivism, in which you guide others instead of only thinking of your own goal.

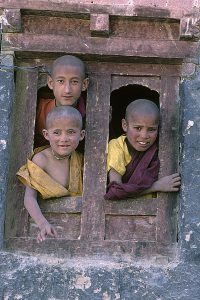

The highest monks, called lamas, spend most of their time helping other persons to practice a more efficient form of meditation. This takes place in monasteries, and over the years, thousands of these monasteries were constructed throughout Tibet and Mongolia. Most families would send one or two sons to a monastery to be enrolled as a monk, but this act was by no means compulsory. Anytime, a monk could choose to leave the monastery to return to his former life as a nomad or a peasant.

In the course of time, various branches of Lamaism evolved, often with rather subtle differences. The most well-known of these is Gelug-pa (‘Yellow Hats’), named after their yellow headgear. Their highest lama is the Dalai Lama (‘Ocean of Wisdom’ in Mongolian), who is a re-incarnation of the eleven-headed Chenresig (‘Buddha of Compassion’) – one of The Buddha’s incarnations. The Dalai Lama is also the secular leader of Tibetans.

The present 14th Dalai Lama was born in Kham, eastern Tibet, in 1935. His name as a lay person was Lhamo Döndrup. In 1939, he was brought to the capital, Lhasa, where he was to reside in the Potala Palace (‘The Palace of a Thousand Rooms’). From that day, he was called Tenzing Gyatso, gyatso being the Tibetan word for the Dalai Lama.

Prior to the Chinese invasion of Tibet in the 1950s, the Potala Palace in Lhasa was the residence of the Dalai Lama. Today, the building is merely a museum. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pilgrim in the Potala Palace, offering yak butter, burned as incense. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tibetan monks, engaged in the art of debating, Sera Monastery, Lhasa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Monks, blowing horns during a Tibetan Buddhist procession in Leh, Ladakh, India, transporting sacred books from the Sankar Monastery. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In areas dominated by Tibetan Buddhism, many boys spend longer or shorter periods of time as apprentices in local monasteries. – Lamayuru, Ladakh. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

During the Chinese Cultural Revolution in the 1960s, large-scale vandalism took place all over Tibet and other Mahayana-dominated areas, causing numerous cultural treasures to be destroyed. This image of a meditating monk, painted on a rock on the kora (pilgrim route) around Lhasa, has been defaced. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gompas

Monasteries in areas dominated by Tibetan Buddhism are called gompas.

These pictures, from Leh, Ladakh, show the red Tsemo Gompa (built 1430), the ruins of King Tashi Namgyal’s old fort (built in the 1500s, left), and a white Maitreya temple. The title Maitreya indicates that this temple is dedicated to the Maitreya Buddha (‘The Future Buddha’), who, in due time, will return to Earth to save humanity. In the bottom picture, black rain clouds darken the sky behind the buildings. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The gompa at Lamayuru, Ladakh, has a dramatic setting, built atop eroded crags. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tengboche Gompa, founded in 1919, is the most important monastery in the Khumbu region, eastern Nepal. It was destroyed twice, in 1934 by an earthquake, and in 1989 by a fire, but was quickly rebuilt. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This gompa at Namobuddha, Kathmandu Valley, Nepal, houses numerous sculptures of tigers, draped in katas (white scarves), which denote respect. Legend has it that on this spot, a Bodhisattva let a tigress kill him, so that she could feed her starving cubs. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A dense layer of clouds disperses, revealing a gompa on a mountain slope near Keylong, Lahaul, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chortens

Chortens are the Tibetan variety of stupas, whose various parts symbolize the elements, the base representing soil, the dome water, the rings or squares above the dome fire, the crescent moon air, and the uppermost point – sometimes a small sun – space.

Row of chortens in morning light, Shey Palace, Ladakh. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

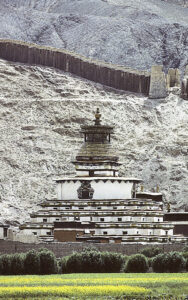

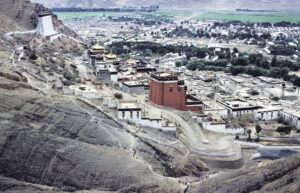

This huge pagoda-shaped chorten is a kumbum, a three-dimensional mandala, depicting the Buddhist cosmos, situated in the Palcho Monastery, Gyantse, Tibet. The word kumbum is often translated as ‘one hundred thousand holy images’. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This wall painting in the kumbum depicts Palden Lhamo, a goddess who protects the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government, having been instigated in this role by the Second Dalai Lama, Gendun Gyatso (1475–1542). Her wisdom and compassion will overcome every obstacle. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Early in the morning, a chorten stands out against the barren hills surrounding Tso Kar, a saline lake in Ladakh. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Strings with prayer flags surround these chortens at the pass Kunzum La, Spiti, Himachal Pradesh. They are adorned with paintings of snow lions, a mythical creature of Central Asia, which, according to traditional folklore, controls mountains and glaciers. It symbolizes strength, fearlessness, and joy. Mani stones (see below) have been placed on one of the chortens. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mani stones

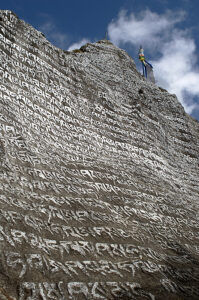

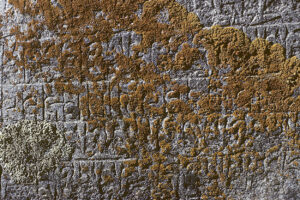

Mani stones are stones, rock walls, or slabs, covered in chiseled Buddhist mantras, the most common of which is Om Mani Padme Hum, which loosely translates as ‘Hail Jewel in the Lotus Flower’ – a symbol of The Buddha.

This mani stone shows the meditating Buddha and two of his disciples, Namche Bazaar, Khumbu, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This huge rock near Namche Bazaar, Khumbu, Nepal, is covered in chiseled mantras. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Morning fog envelops these mani stones near Phortse, Khumbu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These cairns near the village of Ghat, Khumbu, consist of mani stones. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Searching for food, this dzopkio, a cross between a yak and a cow, is walking past a mani stone in Khumbu. These animals are used for transportation at lower altitudes instead of yaks, as these do not thrive below 3,000 m altitude. The cluster of plants to the left is Sikkim spurge (Euphorbia sikkimensis), which grazing animals will not touch, as it is toxic. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Over the years, numerous mani stones are covered in colourful lichens, and on some of the older slabs, the carved mantras can hardly be seen anymore. – Langtang National Park, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Prayer flags

Buddhist prayer flags are coloured pieces of cloth, on which mantras are printed. They are always placed in this order: blue, white, red, green, and yellow. When these flags flutter in the wind, the mantras are dispersed into space, for the benefit of humankind.

Prayer flags are ubiquitous in the Himalaya, here at Annapurna Base Camp, Annapurna Sanctuary, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Prayer flags, illuminated by the rising sun, Fanga, Gokyo Valley, Khumbu, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Prayer flags, outlined against dark rocks, Ulley, Ladakh, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Prayer flags, fluttering in the wind on a rocky ridge beneath King Tashi Namgyal’s old fort, built in the 1500s, near Leh, Ladakh. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Morning sunshine illuminates a chorten and countless prayer flags, Shermatang, Helambu, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Prayer wheels

Inside Tibetan prayer wheels are sheets of paper with written mantras. When the wheel is turned, by hand or by running water in a stream, the mantras are dispersed into the Universe.

This huge prayer wheel near Pangboche, Khumbu, is turned by running water. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Another huge prayer wheel, situated in a Nyingma-pa monastery in Manali, Himachal Pradesh, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

While circumambulating the huge Swayambhunath Stupa in Kathmandu, Nepal, these Tibetan pilgrims are turning long rows of prayer wheels. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Tibetan woman, clad in traditional dress, is turning her prayer wheel beneath the Swayambhunath Stupa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This dog has found a peaceful resting place, next to a huge prayer wheel in Upshi, Ladakh. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Incense

Most visitors to Buddhist temples place burning incense sticks in sand in metal thuribles, which are often adorned with various figures.

This girl is igniting incense sticks in the Wat Pho Temple, Bangkok, Thailand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Incense thuribles in the garden surrounding the Tran Quoc pagoda, Hanoi, Vietnam. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tashilhunpo – a Mahayana monastery

As opposed to most other Tibetan monasteries, this huge Mahayana monastery, situated in Shigatse, Tibet, did not suffer much damage during the Cultural Revolution.

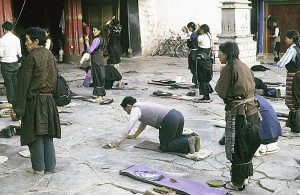

A pilgrim route, several kilometres long, the so-called kora, has been established around the gompa, and before entering the monastery, pilgrims walk along this route. Some pilgrims prostrate all the way around the kora, lying down and stretching their arms in front of them, as far as they can reach. On this spot, they place their rosary, after which they get up, walk the few steps to the rosary, and prostrate again – repeating this procedure countless times.

Tashilhunpo Gompa, seen from the kora. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Prayer flags adorn the kora, and in clay ovens, juniper branches are burned as incense. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

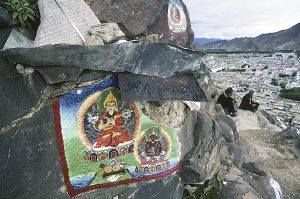

Countless mani walls have been erected along the kora. This slab is adorned with painted Buddha images. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female pilgrim, prostrating all the way around the kora. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This female Tibetan pilgrim is touching a wall inside Tashilhunpo. This sacred spot has turned black from offerings of yak butter, mixed with dirt from thousands of hands. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This wall painting inside Tashilhunpo depicts supernatural creatures from the Central Asian mythology: a dog with fish-head; a snow-lion with elephant trunk, and with a conch and a sea anemone attached to the hind part of its body; and a snow-lion with head, wings, and talons of a feng-huang (often erroneously called Chinese Phoenix). The feng-huang is described on the page Religion: Daoism. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Jokhang – a Mahayana temple

The Jokhang Temple in Lhasa is the most important Buddhist temple in Tibet. After functioning as a pig pen during The Cultural Revolution, this beautiful temple has regained its importance as a pilgrimage centre. This temple is described in depth on the page Travel episodes – Tibet 1987: Tibetan summer.

Early in the morning, fragrant juniper branches are burned as incense in front of the Jokhang Temple. Note the dharma wheel in the background. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pilgrims, prostrating in front of the temple. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

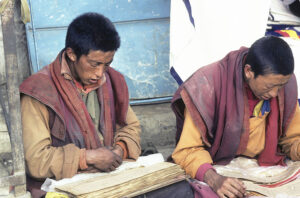

Outside the temple, these monks are busy studying sacred texts. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bodhnath – a Mahayana stupa

One of the largest stupas in the world is Bodhnath, in Kathmandu, Nepal. Around it, a town has sprung up, dominated by Tibetans, who are descendants of fugitives from Tibet, fleeing the Chinese supremacy.

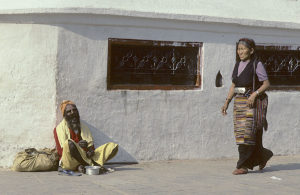

Buddhist pilgrims believe that by distributing coins among the poor during their pilgrimage, they will improve their karma (the sum of their good and bad deeds), and thus have a better chance of reaching a higher position in their next life. Naturally, this has been noticed by beggars, mainly from India, who migrate in large numbers to Buddhist temples during festivals.

The great Bodhnath Stupa, adorned with hundreds of Tibetan prayer flags. The birds on the dome are pigeons, which are being fed here every day. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

While circumambulating the Bodhnath Stupa, this Tibetan woman is passing by a beggar. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This man ignites numerous tiny oil-lamps as an offering. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

During Losar, or Tibetan New Year, the stupa is decorated with thousands of new prayer flags, on which mantras are printed. The flags are always hung on the strings in this order: blue, white, red, green and yellow. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Likewise during Losar, crocus stamens are soaked in water, which is then sprayed on the dome to form semi-circles. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Celebrating Losar, Tibetan monks throw tsampa (barley flour) into the air as an offering. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

While reading, this Buddhist monk seeks shelter from the fierce sunshine beneath an umbrella. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The following three pictures show people, celebrating the birthday of The Buddha at Bodhnath.

Pilgrims, offering rice at a chaitya (described above in the caption Meditating Buddhas). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This woman is igniting hundreds of mustard oil lamps. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Monks, playing on flutes made from human femurs. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In a Tibetan monastery near Bodhnath, monks perform an initiation ceremony.

The leader of the ceremony is the young monk to the right, instructing the man in colourful garments, who is being initiated. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Monks, chanting from holy scripts. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young monk, blowing a huge horn. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Uploaded April 2016)

(Latest update February 2025)