Quotes on Nature

Ravnekilde, a spring in Rold Skov, Jutland, Denmark, with vegetation of the mosses Palustriella commutata and Brachythecium rivulare, and also a variety, hydrophilus, of common sorrel (Rumex acetosa). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spring in a beech forest, eastern Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

I’m going out to clean the pasture spring;

I’ll only stop to rake the leaves away

(And wait to watch the water clear, I may):

I sha’n’t be gone long. – You come too.

American poet Robert Frost (1874-1963), in his poem The Pasture, from North of Boston, 1915.

“Inman put the dawn to his back and set out walking west. All that morning he felt stunned and wretched. His head ached in accordance with the beat of his pulse and felt as if his skull was about to fall into a great number of pieces at his feet. From a fencerow he gathered a wad of the feathery leaves of yarrow and tied it to his head with the stripped stem of the plant. The power of yarrow is to draw out pain, which to an extent it did. The leaves waggled in time with his tired walk, and he spent the morning watching the shadow of them move before him down the road.”

American author Charles Frazier (born 1950), in his excellent novel Cold Mountain, 1997.

In his novel Lykkelige Kristoffer (‘Lucky Kristoffer’, 1945), Danish author Martin A. Hansen (1909-55) relates the adventures of a group of lazy good-for-nothings during a war in Halland, Sweden, in the 1500s. One of them is a clergyman who describes the wonderful healing properties of the common yarrow (Achillea millefolium):

“No herb curbs bleeding and cures wounds as the yarrow. I knew a farmer from Hunnested who stumbled into his hand-mower, and the blade cut the cartilage off his nose just beneath the bone. He plucked a wad of yarrow, went home and told his wife: ”Gumme, chop this yarrow with a bit of unsalted pork, while I hold the nose in place.” Then they tied the nose and covered it with the yarrow ointment, and four weeks later the nose was healed.”

For thousands of years, this plant has been utilized to curb bleeding. It was already mentioned as a medical herb in De simplicium medicamentorum facultatibus, written by Greek-Roman physician, surgeon, and philosopher Aelius Galenus (c. 129-210 A.D.), also known as Claudius Galenus or Galen of Pergamon. English herbalist John Gerard (c. 1545-1612) informs us that during the Trojan War the Greek hero Achilles used yarrow to stop bleeding on wounded soldiers. The role of the plant in traditional medicine is described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

“From a fencerow he gathered a wad of the feathery leaves of yarrow.” – This yarrow was photographed in Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“The wind blowed so hard from the northeast, that, cold as it was, we resolved to see the breakers on the Atlantic side, whose din we had heard all the morning; so we kept eastwards through the Desert, till we struck the shore again northeast of Provincetown, and exposed ourselves to the full force of the piercing blast. There are extensive shoals there over which the sea broke with great force. For half a mile from the shore it was one mass of white breakers, which, with the wind, made such a din that we could harly hear ourselves speak.”

American writer Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862), in his book Cape Cod, first published 1865.

At dusk, a sea-going gale blows off foam from the top of breakers, Pemaquid, Maine, United States. Note the gulls in the lower picture. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Remember it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.” That was the only time I ever heard Atticus say it was a sin to do something, and I asked Miss Maudie about it.

“Your father’s right,” she said. “Mockingbirds don’t do one thing but make music for us to enjoy (…) but sing their hearts out for us. That’s why it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.”

American author Nelle Harper Lee (1926-2016), in her novel To Kill a Mockingbird, 1960.

Northern mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos), sitting in a loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), Assateague Island, Maryland, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Northern mockingbird, Long Island, New York. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Autumn is a second spring, when every leaf is a flower.”

French writer and philosopher Albert Camus (1913-1960).

Gorgeous foliage of red maple (Acer rubrum). In autumn, the leaves turn orange, scarlet, or yellow – or sometimes all three colours on the same leaf. – Adirondacks, New York State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Yes, a corn field is nature to me. Personally, I experience a feeling of nature by standing next to a blooming field of rapeseed. It’s possible that others see a biodiverse desert, but I don’t.”

Esben Lunde Larsen, Danish minister of the environment and foods 2016-18, in the newspaper Morgenavisen Jyllandsposten, April 29, 2016. I guess that he was a minister of foods, very much more than he was a minister of the environment. Well, the entire government at that time was opposed to nature conservation, which was obvious to all, when it combined these two ministeries!

Few things could be further from nature than a uniform, well sprayed field of rapeseed, whose colour is a menace to the eye, and, furthermore, has an unpleasant odour. – Stevns, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Poison ivy grew in thick beds that stretched as far as Inman could see through the woods. It climbed the pine trees and spread among their limbs. The falling needles caught in the tangled ivy vines and softened the lines of the trunks and limbs and formed heavy new shapes of them, until the trees loomed like green and grey beasts, risen out of the ground. (…) Blisters of poison ivy beaded up on his hands and forearms from his flight through the flatwoods.”

American author Charles Frazier (born 1950), in his excellent novel Cold Mountain, 1997.

The only thing that poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans, formerly called Rhus radicans) has in common with the true ivy (Hedera) is its climbing habit. This plant, which belongs to the sumac family (Anacardiaceae), is very common in the eastern half of North America, from Labrador south to Texas and Florida.

As with other members of this genus, poison ivy contains the poisonous urushiol, which causes rashes and other allergic reactions in some people. In his delightful book All about Weeds, American botanist Edwin Spencer (1881-1964) writes about poison ivy: “With allitterations, we may almost truthfully say ‘the worst weed of the woods’ or ‘the worst weed of waste places’ is the poison ivy. If its toxin affected the skin of every one as it does that of a few, it would not be necessary to qualify these allitterations. They would be literally true. This is the one weed, however, that every one who lives in the country, and all who visit it, should know. Those who are immune to its poison have nothing to fear, but no one knows whether he is immune or not until he has come in contact with some part of the plant. If he is susceptible he will long remember that day, and if he is wise he will develop his observational powers, until they equal those of a first-class botanist, when he approaches a likely habitat of this snake of the woods.”

In his excellent book The Green Pharmacy, American botanist and herbalist James A. Duke (1929-2017) recommends the juice of soapwort (Saponaria officinalis) as the best remedy, if you have been into contact with poison ivy or other Toxicodendron species. Smear the juice over the affected area to neutralize the poison.

Poison ivy, climbing up a black locust (Robinia pseudacacia), Sands Point Preserve, Long Island. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flowering poison ivy, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Tennessee. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“But if I were required to name a sound, the remembrance of which most perfectly revives the impression which the beach has made, it would be the dreary peep of the piping plover (Charadrius melodus). Their voices, too, are heard as a fugacious part in the dirge, which is ever played along the shore for those mariners who have been lost in the deep since it was first created.”

(…)

“In summer I saw the tender young of the piping plover, like chickens just hatched, mere pinches of down on two legs, running in troops, with a faint peep, along the edge of the waves.”

American writer Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862), in his book Cape Cod, first published 1865. – A fuga, or fugue, is a piece of classical music, built over a theme, which is repeated and variated.

Piping plover, observed at its breeding place at Breezy Point, Long Island, New York State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Below are four quotes from the booklet Chrut und Uchrut (in English called Weeds – a useful booklet on medicinal herbs), written in 1911 by Swiss priest and herbalist Johann Künzle (1857-1945).

“When someone is green like a frog, skinny as a poplar, loses weight daily, his good humour too, and doesn’t even cast a shadow, make him take a teaspoonful of wormwood tea every two hours.”

Absinth wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) is dealt with in detail on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Absinth wormwood, Degerhamn, Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“This very disdained herb is undoubtedly the principal, best and most prevalent of all healing herbs. God has scattered it along all roadsides, in all meadows, and on all banks, as well as in all climates, so that we shall always have it on hand.”

Künzle is referring to the greater plantain (Plantago major), which is described in depth on the page Plants: Urban plant life.

Greater plantain, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Hares, rabbits, birds, and cattle like it very much. The dandelion has existed since the creation of the universe and sows itself.”

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) is described in depth on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Seed heads of dandelion, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“The application of Herb Robin is also very effective against abscesses and inflammations of cattle. Glory be to God.”

Herb Robert (Geranium robertianum) is described on the page Plants: Railway flora.

Herb Robert, growing beside a rivulet, Døndalen, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Below is a number of quotes from a book, Naturhistorie for Folkeskolen (‘Natural History for Primary and Lower Secondary School’), written by Danish school teacher Christian Vilhelm Balslev (1860-1935), and first published in 1909. This book was in use in Danish schools until the late 1950s, and I had the great honour of being taught all this horrible nonsense, when I was a boy.

“The dog is a domestic animal almost all over the world. Actually, it is a carnivore, and its teeth are much like those of a fox. The dog is clever and faithful and is of excellent use in many ways.”

The domestic dog is dealt with in detail on the page Animals: Animals as servants of Man.

Wire-haired dachshund, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“The wolf resembles a large, grey dog. It is often a coward, but in winter, when the wolves are hungry, they can be very dangerous to both people and cattle.”

The wolf (Canis lupus) is described on the page Animals – Mammals: Dog family.

Mexican wolf, subspecies baileyi, Tucson Desert Zoo, Arizona, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“The domestic cat is also a carnivore, and it rarely eats anything but meat. We keep it as a domestic animal because of its great ability to catch mice; but it never becomes as faithful as a dog, and is not as clever.”

The domestic cat and its origin are described on the page Animals: Animals as servants of Man.

Kittens, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“The tiger resembles a giant cat and is yellowish-brown with dark stripes. It is the most dangerous of all carnivores. In India, where the tiger lives, they kill several hundred people every year. In the daytime, the tiger sleeps in the shrubs, but in the evening, it lies in wait at the river banks for animals, which come down to drink, and attacks them.”

The sad fate of the tiger (Panthera tigris) is related on the page Folly of Man.

Tiger, Kanha National Park, Madhya Pradesh, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“The seal cannot walk, because its feet point backwards; when on land, it pushes itself or wriggles forward. But in the sea, it is as fast as a fish (…) The seal glides easily through the water, because its head and body merge into each other gradually, and because its hairs are short and greasy. (…) The Greenlanders hunt them with harpoons, and there is no animal, of which they have so much use. Here at the coasts of Denmark, the seals do some damage by eating fish.”

Harbour seal (Phoca vitulina), resting on a coastal rock, Point Lobos, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“The mole lives in the ground. (…) It mainly eats worms and larvae, and it is so gluttonous, that in one day it can eat more than its body weight.”

Mole (Talpa europaea) in its den, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg, arranged photograph)

“The monkeys are fun to look at, because their behaviour is so odd, and they want to imitate, whatever they observe people doing.”

Numerous monkey species are described on the page Animals – Mammals: Monkeys and apes.

Young orphaned orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus), Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre, Sabah, Borneo. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“The magpie always lives near houses or farms, and it loves to steal silverware and other shining objects.”

The magpie (Pica pica) is described on the page Animals – Birds: Corvids.

A small part of a flock of about a hundred magpies, gathering at their night roost in willow trees, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“The swan is even larger than the goose and has a very long neck, which is of much use, when it has to reach the plants on the bottom of the water.”

The mute swan (Cygnus olor) is described on the page Animals – Birds: Swans.

Mute swan, Copenhagen, Denmark (top), and incubating mute swan, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“The gull lives at the beach. It does not swim as well as a duck, but is a better flier.”

Numerous gull species are described on the page Animals – Birds: Gulls, terns and skimmers.

Herring gull (Larus argentatus) on its breeding site, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“A lammergeier came down from the sky and took off my cock.”

Colonel J. Davidson, Indian Staff Corps, Calcutta, in his book Notes on the Bashgali (Kafir) Language, 1901.

Whether it be one cock or the other, is an open question.

The lammergeier (Gypaetus barbatus), also known as bearded vulture, mainly feeds on carcasses, notably bones, which it carries high, dropping them on a rocky surface, whereupon it eats the shattered fragments. However, there are also examples of it attacking farm chickens.

Lammergeier, Govindghat, Uttarakhand, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

It is white outside:

Kyndelmisse strikes at its utmost,

Exceedingly biting and severe –

White below, white above,

The forest tree has been thickly powdered,

Just like my apple orchard.

(…)

With all my heart I long for spring,

But winter grows more severe;

Again, the wind is coming out of the North!

Come, Southwester, to subdue the frost!

Come with your wings of fog!

Come and free the tied earth!

Steen Steensen Blicher (1782-1848), Danish poet, in his poem Ouverture, one in a collection of poems named Trækfuglene (‘Migratory Birds’), 1838.

Kyndelmisse is an old Danish term for February 2nd, when – so it was told – you still had to face the second half of the winter. At this time, the winter was often at its most severe, and, incidentally, the winter of 1838, when this poem was written, was one of the coldest ever experienced.

Fence, covered in rime, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Snowdrift of an unusual shape, formed by whirlwinds in front of a building, Nature Reserve Tipperne, Ringkøbing Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Snow-covered field with stems of scentless false mayweed (Matricaria perforata, left) and yarrow (Achillea millefolium), Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Nuttall’s flowering dogwood makes a fine show when in bloom. The whole tree is then snowy white. The involucres are six to eight inches wide. Along the streams it is a good-sized tree thirty feet high, with a broad head when not crowded by companions. Its showy involucres attract a crowd of moths, butterflies, and other winged people about it for their own, and, I suppose, the tree’s advantage.”

John Muir (1838-1914), Scottish-American writer and environmentalist, in his book My First Summer in the Sierra, 1911.

Nuttall’s flowering dogwood, today better known as Pacific dogwood (Cornus nuttallii), Yosemite National Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“If we diligently consider the nature of this aconite [Aconitum napellus] and investigate its powers, we must conclude that it does more harm than good, and has been misused more than the opposite. It has become a common habit among women, who are about to give birth, to strew flowers and leaves of this herb as decoration in windows and other places in bedrooms and living-rooms. They also often hand it to children to play with, unaware of its content of poison, which can easily kill a human being. Were it not for God’s great protective powers, parents would often be overcome by grief due to their inadvertence. (…) So great is the toxicity of this herb that if the point of an arrow is smeared with its juice, the person who is hit by this arrow, must inevitably die.”

Danish physician and herbalist Simon Paulli (1603-1680), in his book Flora Danica, 1648.

Aconites are further described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Common monkshood (Aconitum napellus), Alto Gallego, Aragon, Spain (top), and Umbal Valley, Tirol, Austria. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The butterfly

Flitting from flower to flower

Ever remains mine,

I lose the one

That is netted by me.

Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), Indian poet, in a collection of poems, titled Fireflies, 1928.

The Paris peacock swallowtail (Papilio paris) is distributed from north-western India eastwards to southern China and Taiwan, and thence southwards through Southeast Asia to Sumatra and Java.

This gorgeous butterfly is named for Prince Paris of Troy, son of King Priam and Queen Hecuba. According to Greek mythology, King Peleus was about to marry the beautiful sea nymph Thetis, but, unfortunately, they had forgotten to invite the goddess of strife, Eris, to the wedding. As a revenge, Eris let a golden apple roll in among the guests, and in the fruit skin she had carved: “For the most beautiful one.”

Three of the goddesses, Hera, Athene, and Aphrodite, began arguing, to whom of the three the title should be bestowed. Zeus advised them to go to Troy to consult Prince Paris. Off they went, and upon arrival in Troy, each of them promised Prince Paris a reward, if he chose her: Hera promised him power, Athene fame and wisdom, and Aphrodite the most beautiful woman. He chose the latter – hereby indirectly causing the long siege of Troy, related in Homer’s poem Iliad.

Male Paris peacock swallowtail (Papilio paris ssp. paris f. decorosa), sucking moisture from sand, Annapurna, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The chestnut tiger (Parantica sita) belongs to Danainae, which includes monarchs, tigers, nymphs, and crows, a subfamily of the huge brush-foot family (Nymphalidae). This butterfly is found from northern Pakistan eastwards along the Himalaya to Southeast Asia, China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan, Russian Ussuriland, and the island of Sakhalin.

Chestnut tiger, feeding in a species of boneset, Eupatorium schimadae, Longdongwan Cape Trail, north-eastern Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The peacock pansy (Junonia almana) is distributed from India and Sri Lanka eastwards to China, Taiwan, and Japan, and thence southwards to Indonesia. It is very common, living in a wide variety of habitats up to altitudes around 1,000 m. It is one among c. 33 species of this genus, which belongs to the huge brush-foot family (Nymphalidae).

Peacock pansy, encountered in Pokhara, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Conversation on the mountain

問余何事(意)棲碧山

笑而不答心自閒

桃花流水杳然去

別有天地非人間

This poem has been translated in various ways. One version is given below.

You ask why I stay on the green mountain?

I smile, but do not answer, my heart is at peace.

A peach blossom is carried far off by a flowing stream,

In this world apart from the human world.

Chinese poet Li Bai (Li Bo) (701-762).

Clouds, illuminated by the morning sun, behind the jagged peaks of Lhotse (8511 m), Khumbu, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Still, so tenuous is the existence of this species that one-fourth to one-third of all the Nilgiri tahr in existence were within my view from Anaimudi Peak.”

George B. Schaller (b. 1933), German-American biologist and environmentalist, in his book Stones of Silence: Journeys in the Himalaya (1980), after estimating the total population of the Nilgiri tahr (Nilgiritragus hylocrius) at c. 1,500. Since then, conservation measures have caused its numbers to increase to c. 3,100.

Formerly, this species, which is restricted to mountains of South India, was placed in the genus Hemitragus, together with the Himalayan tahr (H. jemlahicus) and the Arabian tahr (H. jayakari, today called Arabitragus jayakari). However, genetic research has shown that it is more closely related to sheep of the genus Ovis than to the other tahrs, and, consequently, it was moved to a separate genus.

Eravikulam National Park, Kerala, where these pictures were taken, is a stronghold of the Nilgiri tahr, housing an estimated 700-800 individuals, app. one-fourth of the total population. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In the late 1990s, tourists began feeding the tahr in Eravikulam, and the animals lost their fear of people. This practice has since been banned. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offence.

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That wants it down.

Robert Frost (1874-1963), American poet, in his poem Mending Wall, 1914.

Over time, many stone walls become covered by large moss cushions, and they often constitute valuable habitats for many different plants and animals.

Moss-covered stone fence, Kristianopel, Blekinge, Sweden. Common polypody (Polypodium vulgare) also grows on the wall. The brown leaves are from oak (Quercus) and beech (Fagus sylvaticus), whereas the yellow leaf is from Norway maple (Acer platanoides). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Moss-covered stone fence, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This stone fence was seen at Borgholm, Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“On Hirsholmen [one of a group of islets in northern Kattegat, Denmark] there used to be a community, complete with a school and everything. (…) It is a brilliant bird locality, also called ‘Isles of the black guillemots.’ This little, blackish-brown auk with a large white wing-patch and bright red legs is present here as never before. Anyone can see them, when the boat lays to in the tiny harbour. If you arrive in the morning, black guillemots are swarming around the stone jetties, in which they breed. (…) For hundreds of years, the sandvich tern has been constantly present on this island, breeding in the thousands.”

Jens Gregersen (b. 1952), Danish artist and author, in his book Årets ring. Fuglene og landet (’Circle of the Year. Birds and landscape’), 2008.

The quote ‘Isles of the black guillemots’ refers to a Danish book, entitled De Sorte Tejsters Øer, written by C.A. Rasmussen and published in 1932.

The black guillemot (Cepphus grylle) breeds abundantly on the stone jetties in the tiny Hirsholm harbour. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

” For hundreds of years, the sandvich tern has been constantly present on this island, breeding in the thousands.” – Sandvich terns (Thalasseus sandvicensis), Hirsholm, 2017. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Information board, Trounson Kauri Park, New Zealand.

Trounson was born in England, but emigrated to New Zealand in 1862, where he purchased c. 970 hectares of bush at Paparoa, and later acquired c. 1,375 ha in the Kaihu Valley.

In 1890, when the timber industry threatened to wipe out all giant kauri trees (Agathis australis), Trounson set aside 22 ha and established a Scenery Preservation Club. Later, a further 364 ha were added, and the area was officially opened as Trounson Kauri Park in 1921. Today, the scenic reserve covers 586 ha.

In 1952, the nearby Waipoua Forest, covering c. 80 km2, was proclaimed a forest sanctuary. Today, these two forests constitute the only larger area of kauri forest remaining in New Zealand. You may read more about the sad fate of these magnificent trees on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees.

Ancient kauri tree, Waipoua Forest. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Far into the 1800s, most botanists only recognized one species of butterfly-orchid [in Europe]. However, in 1862, Charles Darwin, in a masterly way, describes in his work: On the various Contrivancies by which Orchids are fertilised, that the tiny differences in the sexual organs are so significant that, biologically speaking, there must be two species (lesser and greater butterfly-orchid). (…) In the early 1800s, the brilliant biologist Salomon Th. Drejer, in Flora Danica, described a new butterfly-orchid, the long-spurred butterfly-orchid, which is larger than the more common lesser butterfly-orchid. It blooms two weeks earlier than lesser butterfly-orchid, despite growing in dark hardwood forests, as opposed to lesser butterfly-orchid, which grows in moors and dry grasslands.”

Bernt Løjtnant (1946-2020), consultative biologist, in his and Jens Gregersen’s book Blomsternes Danmark (‘The Denmark of Flowers’), 1999.

The greater butterfly-orchid (Platanthera chlorantha) is distributed from central Norway and Sweden southwards to the Pyrenees, southern Italy, and northern Greece, and from Ireland eastwards to the European part of Russia. It is also common in the Caucasus and has scattered populations in in Spain, Morocco, and Turkey.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek platus (‘broad’) and anthera (‘anther’), referring to the broad anthers of this species, whereas the specific name is derived from Ancient Greek khloros (‘green’) and anthos (‘flower’), referring to the flower colour, which is sometimes slightly greenish.

The pictures below were taken in a spruce plantation near Hjortsballe Gavlbanker, central Jutland, Denmark, which harbours a huge population of greater butterfly-orchid, besides many other interesting plant species, such as southern marsh orchid (Dactylorhiza majalis ssp. integrata var. junialis, also called D. praetermissa), and perhaps the largest population in Denmark of round-leaved wintergreen (Pyrola minor).

(Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The lesser butterfly-orchid (Platanthera bifolia) is more slender than greater butterfly-orchid and grows in drier areas, such as heaths and grassy slopes. It has a very wide distribution, from western Europe eastwards to central Siberia, and from northern Norway southwards to North Africa, southern Italy, northern Turkey, and the Caucasus. Populations of Platanthera in the Far East are sometimes regarded as this species, sometimes as several separate species.

In these pictures from a military area near Jægerspris, northern Zealand, Denmark, lesser butterfly-orchid grows together with heath spotted orchid (Dactylorhiza maculata), common stitchwort (Stellaria graminea), and common sorrel (Rumex acetosa), among others. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

As its name implies, the long-spurred butterfly-orchid (Platanthera bifolia ssp. latiflora) has a very long spur, which is almost completely straight. Today, it is regarded as a subspecies of the lesser butterfly-orchid, which is odd, considering that it only grows in forests, and it blooms two weeks earlier.

Long-spurred butterfly-orchid, photographed in the Vrata Valley, Triglavski National Park, Slovenia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Sabine’s gulls are moderately irascible, performing a reserved attack, while displaying superb elegance. Their voices are sharp and reserved as those of terns. Their flight is soft and elegant, butterfly-like as that of the little gull [Hydrocoloeus minutus]. Graphically, too, they are magnificent, displaying a staunch colour scheme. I am referring to their hood, which is of a unique colour; steel-violet, I would call it. Around the eye is a succulent red colour, repeated around the gape. The yellow point of the bill is a gradual dissolvement of a dark bill colour.”

Jens Gregersen (b. 1952), Danish artist and author, in his book Arktisk sommer (‘Arctic Summer’, published in Danish), 2014.

Sabine’s gulls (Xema sabini) on their breeding ground, Kosa Ruskaya Koshka (‘Russian Cat’s Spit’), Chukotka, Siberia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Outside my window, some alders are growing so close to the edge of the water that their roots, like knotty old-man’s-fingers, cling to the pebbles on the shore, partly submerged in the water, even when the water level is low.”

Gunnar Brusewitz (1924-2004), Swedish artist and writer, in his book Strandspegling. Naturupplevelser i tid och rum (‘Coastal reflections. Nature experiences in time and space’), 1979.

These exposed roots of common alder, growing on a lake shore in central Jutland, Denmark, resemble “knotty old-man’s-fingers.” (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Come with rain, O loud Southwester!

Bring the singer, bring the nester,

Give the buried flower a dream.

Robert Frost (1874-1963), American poet, in his poem To the Thawing Wind, 1915.

In northern Europe, species of butterbur (Petasites) are among the earliest flowers to sprout in spring. These pictures show white butterbur (P. albus), photographed in eastern Jutland, Denmark (top), and common butterbur (P. hybridus), observed in eastern Funen, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“(…) the racket-tailed drongo is a never-ending source of pleasure and interest for, in addition to being the most courageous bird in our jungles, he can imitate to perfection the calls of most birds and of one animal, the cheetal [spotted deer, Axis axis], and he has a great sense of humour. Attaching himself to a flock of ground-feeding birds – junglefowl, babblers, or thrushes – he takes up a commanding position on a dead branch and, while regaling the jungle with his own songs and the songs of other birds, keeps a sharp look-out for enemies in the way of hawks, cats, snakes, and small boys armed with catapults, [the author’s reference to himself] and his warning of the approach of danger is never disregarded. His services are not disinterested, for in return for protection, he expects the flock he is guarding to provide him with food. His sharp eyes miss nothing, and the moment he sees that one of the birds industriously scratching up or turning over the dead leaves below him has unearthed a fat centipede or a juicy scorpion he darts at it screaming like a hawk, or screaming as a bird of the species he is trying to dispossess does when caught by a hawk. Nine times out of ten he succeeds in wresting the prize from the finder, and returning to his perch kills and eats the titbit at his leisure, and having done so continues his interrupted song.”

Jim Corbett (1875-1955), hunter, writer, and conservationist, in his book Jungle Lore, 1953.

Greater racket-tailed drongo (Dicrurus paradiseus), feeding on flowers of a coral tree (Erythrina stricta), Periyar National Park, Kerala, South India. This picture clearly shows, why the bird is called ‘racket-tailed drongo’. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“A genuine Danish term, [rather than ’Indian Summer’] describing the late return of the summer, is ’Flying Summer’. On calm and sunny days, the stubble fields are covered in myriads of young spiders’ webs, creating a transparent silk carpet, as far as the eye can reach. And it reaches far on a glass-clear September afternoon.”

Jens Gregersen (b. 1952), Danish artist and author, in his book Årets ring. Fuglene og landet (’Circle of the Year. Birds and landscape’), 2008.

”(…) myriads of young spiders’ webs, creating a transparent silk carpet, as far as the eye can reach.” – Nature Reserve Tipperne, Ringkøbing Fjord, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Many other pictures of spiders’ webs are shown on the page Animals: Cobwebs.

“In June and early July there will be the delicate, three-petaled flowers of the mariposa lily. This plant has a bulb-shaped root that tastes a great deal like a potato. Native Americans used it widely as a food source, as did thousands of hungry Mormon settlers in Utah, who were so thankful for its presence in those early years that they ended up making it the Utah state flower.”

Gary Ferguson (b. 1956), American author, in his book Rocky Mountain Walks, 1993.

Calochortus is a genus of beautiful lilies with about 78 species, almost exclusively growing in the western United States. These plants can be divided into three distinct groups: mariposa tulips, or mariposa lilies, which have open, wedge-shaped petals; globe lilies with globe-shaped flowers; and cat’s ears and star tulips, which have erect, pointed petals.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kalos (‘beautiful’) and khortos (‘grass’), alluding to the grass-like leaves of many of the species.

Kennedy’s mariposa tulip (Calochortus kennedyi) comes in two colour forms, red and yellow. Both pictures were taken in Arizona. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Arizona mariposa tulip (Calochortus ambiguus), Mazatzal Mountains, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

White globe lily (Calochortus albus), Point Lobos State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The flower of elegant cat’s ear (Calochortus elegans) does indeed resemble a hairy cat’s ear. – Leggett, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Of birds there were many varieties, and of flowers there was a great profusion, the most beautiful of which was the white butterfly orchid. These orchids hang down in showers and veil the branch or the trunk of the tree, to which their roots are attached. One of the most artistic nests I have ever seen was that of a Himalayan black bear, made in a tree, on which orchids were growing.”

Jim Corbett (1875-1955), British author, hunter, and conservationist, in his book The Temple Tiger, And More Man-eaters of Kumaon, 1954.

“These orchids hang down in showers…” – Corbett refers to the shining coelogyne (Coelogyne nitida), here photographed in the Modi Khola Valley, Annapurna, central Nepal, where it is very common. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The woods are lovely,

Dark and deep.

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

Robert Frost (1874-1963), American poet, in his poem Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening, 1922.

Frozen pond, Massachusetts, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“No one who looks into a gorilla’s eyes – intelligent, gentle, vulnerable – can remain unchanged, for the gap between ape and human vanishes; we know that the gorilla still lives within us. Do gorillas also recognize this ancient connection?”

George B. Schaller (b. 1933), German-American biologist and environmentalist, in his article Gentle Gorillas, Turbulent Times, National Geographic, 188 (4): 66, 1995.

Resting female mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei), Bwindi National Park, Uganda. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Climb the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you, and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves.”

John Muir (1838-1914), Scottish-American writer and environmentalist, in his book Our National Parks, 1901.

At dawn, sun beams spread star-like into space behind the sacred peak of Ama Dablam (6856 m), Khumbu, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Inman could see west for scores of miles. Crest and scarp and crag, stacked and grey, to the long horizon. Cataloochee, the Cherokee word was. Meaning waves of mountains in fading rows. And this day, the waves could hardly be differed from the raw winter sky. Both were barred and marbled with the same shades of grey only, so the outlook stretched high and low, like a great slab of streaked meat.”

American author Charles Frazier (born 1950), in his excellent novel Cold Mountain, 1997.

”(…) stacked and grey, to the long horizon.” – Siskiyou Mountains, Oregon. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The wintry hedge was black

The green grass was not seen;

The birds did rest

On the bare thorn’s breast,

Whose roots, beside the pathway track,

Had bound their folds o’er many a crack

Which the frost had made between.

Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822), British poet, in his poem The cold earth slept below, 1815.

“The wintry hedge was black…” – Hedge of pruned poplars (Populus) in winter, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“One of the creatures that intrigued and irritated me most was the dung beetle. I would lie on my stomach with Roger, my dog, squatting like a mountain of black curls, panting, by my side, watching two shiny black dung beetles, each with a delicately curved rhino horn on its head, rolling between them (with immense dedication) a beautifully shaped ball of cow dung. To begin with I wanted to know how they managed to make the ball so completely round. I knew from my own experiments with clay and Plasticine that it was extremely difficult to do, however hard you rubbed and manipulated the material, yet the dung beetles, with only their spiky legs as instruments, devoid of calipers or any other aid, managed to produce these lovely balls of dung, as round as the moon.”

Gerald Durrell (1925-1995), British writer and environmentalist, in his book Birds, Beasts, and Relatives, 1969.

Dung beetles, making balls from zebra dung, Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This dung beetle is rolling a dung ball towards its nesting hole, where it will bury it and lay eggs in it. – Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In Ancient Egypt, Khepri was a solar deity, connected with the dung beetle, or scarab beetle (Scarabaeus sacer), which was sacred, because these beetles roll balls of dung across the ground – an act that the Egyptians saw as a symbol of the forces, which move the sun across the sky. Dung beetles became very popular as amulets and impression seals, called scarab, and they were often depicted on temples, graves etc.

Cartouches with reliefs in the Death Temple of Queen Hatsepsut, depicting dung beetles, a falcon (which was a symbol of the god Horus), an ox, a barn owl (Tyto alba), a bee, a pintail (Anas acuta), a sacred ibis (Threskiornis aethiopicus), and a horned viper (Cerastes cornutus), besides various tools and other items. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“As I stepped clear of this giant slate, I looked behind me over my right shoulder and – looked straight into the tigress’s face. (…) Her head, which was raised a few inches off her paws, was eight feet (measured later) from me, and on her face was a smile similar to that one sees on the face of a dog welcoming his master home after a long absence.

Two thoughts flashed through my mind: one, that it was up to me to make the first move, and the other, that the move would have to be made in such a manner as not to alarm the tigress or make her nervous.

The rifle was in my right hand, held diagonally across my chest, with the safety-catch off, and in order to get it to bear on the tigress, the muzzle would have to be swung round three-quarters of a circle.

The movement of swinging round the rifle, with one hand, was begun very slowly, and hardly perceptibly, and when a quarter of a circle had been made, the stock came in contact with my right side. It was now necessary to extend my arm, and as the stock cleared my side, the swing was very slowly continued. My arm was now at full stretch and the weight of the rifle was beginning to tell. Only a little further now for the muzzle to go, and the tigress – who had not once taken her eyes off mine – was still looking up at me, with the pleased expression still on her face. (…) the movement was completed at last, and as soon as the rifle was pointing at the tigress’s body, I pressed the trigger.

(…) For a perceptible fraction of time the tigress remained perfectly still, and then, very slowly, her head sank on to her outstretched paws, while at the same time a jet of blood issued from the bullet-hole. The bullet had injured her spine and shattered the upper portion of her heart.”

Jim Corbett (1875-1955), British author, hunter, and conservationist, in his book Man-eaters of Kumaon (1944).

In his book Carpet Sahib (1986), author Martin Booth (1944-2004) points out that this incident has been greatly dramatized by Corbett who, in a letter to his sister Maggie, wrote this edition:

“At the lower end of the rock, the bed of the nala [canyon], was on level with the banks. I tip-toed forward without making a sound, and as I cleared the rock I looked over my right shoulder and – looked straight into the tiger’s face. She flattened down her ears and bared her teeth and slipped forward, but by then I had slipped the safety over, and the bullet went straight through her heart. It was all over in a heart beat, and the tiger was dead as nails.”

Quite a different story!

“(…) on her face was a smile similar to that one sees on the face of a dog welcoming his master home after a long absence.” – Tigress (Panthera tigris), Kanha National Park, Madhya Pradesh, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“The fragrant growth of pasque flowers and red clover in the meadow surrounded my small person like a heavenly wave, while I stormed ahead, not being stopped by even the widest ditches, and when finally I reached the brook, lying like a wonderful and breath-taking carpet of rolling velvet and satin in front of me, my swelling boy’s heart was filled with an inexplicable happiness (…).”

Jeppe Aakjær (1866-1930), Danish poet, in his autobiography Fra min Bitte-Tid (‘From my Tiny-Time’), 1928.

”The fragrant growth of pasque flowers and red clover (…)” – Common pasque flower (Pulsatilla vulgaris), Beijershamn, Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

”(…) a wonderful and breath-taking carpet of rolling velvet and satin.” – Stream with aquatic plants, Connetquot River State Park, Long Island, New York. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

My beloved is like a gazelle or a young stag.

Behold, there he is standing behind our wall,

Gazing through the windows,

Looking through the lattice.

Until the cool of the day,

When the shadows flee away,

Turn, my beloved, and be like a gazelle,

Or a young stag on the mountains of Bether.

Song of Solomon, 2:9, 2:17.

”Turn, my beloved, and be like a gazelle.” – Gujarat gazelle (Gazella bennettii ssp. christii) in morning light, Rajasthan, India (top), and gerenuk (Litocranius walleri), Samburu National Park, Kenya. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“(…) a herd of buffalo, one hundred and twenty-nine of them, came out of the morning mist under a copper sky, one by one, as if the dark and massive, iron-like animals with the mighty horizontally swung horns were not approaching, but were being created before my eyes and sent out as they were finished.”

Karen Blixen (1885-1962), alias Isak Dinesen, Danish author, in her book Out of Africa, 1937.

A herd of African buffalo (Syncerus caffer) in morning mist, Tarangire National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“A grove of giant redwood or sequoias should be kept just as we keep a great and beautiful cathedral.”

Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), American president 1901-1909.

The magnificent giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum) is described on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees.

Giant sequoias, Sequoia National Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“A hundred divine epochs would not suffice to describe all the marvels of the Himalaya.”

Sanskrit proverb.

An almost Full Moon is rising behind the sacred mountain of Machhapuchhare (‘Fishtail Peak’) (6,993 m), Annapurna, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Early in the morning, fair-weather clouds are passing above the peak of Thamserku (6,608 m), Khumbu, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Changabang (6,864 m) is a striking white granite mountain, situated in Nanda Devi National Park, Uttarakhand, India. This national park comprises a wilderness area, parts of which are closed to the public. In the foreground, old-man’s-beard lichens (Usnea) are draped around branches of a Himalayan birch (Betula utilis). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Morning sun penetrates a thick layer of clouds, which almost hides the peak of Annapurna III (7,555 m), seen from the Upper Marsyangdi Valley, Annapurna, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In his play A Midsummer Night’s Dream, British poet William Shakespeare (1564-1616) describes a mischievous puck, or spirit, Robin Goodfellow, who meets a fairy, asking her what she is doing. She answers:

And I serve the fairy queen

To dew her orbs upon the green,

The cowslips tall her pensioners be,

In their gold coats spots you see,

Those be rubies, fairy favours,

In those freckles live their saviours,

I must go seek some dewdrops here,

And hang a pearl in every cowslip’s ear.

Modified into modern English:

I serve the fairy queen,

Adding dew drops on her flowers in the grass.

The tall cowslips are her servants.

In their golden coats you can see spots.

Those are rubies, gifts from the fairies.

Their sweet smell comes from those freckles.

Now I must go to find some dewdrops,

And hang a pearl earring on every cowslip flower.

Cowslip (Primula veris) in morning light, Jutland, Denmark. This species is presented in depth on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry, and many other primrose species are described on the page Plants: Primroses. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“But above all other kinds of moss [lichens], which grow in the forests on trees, rocks and other places, the most famous one is Usnea, sev Muscus cranii humani, meaning: ’That moss which grows on human skulls’, which, although rarely, is sometimes found on the skulls of miscreants, who have been beheaded, or otherwise done away with, and whose heads have been placed on a stake.”

Danish physician and herbalist Simon Paulli (1603-1680), in his book Flora Danica, 1648.

Old-man’s-beard lichens (Usnea) are a large, worldwide genus of the family Parmeliaceae, comprising about 600 species. Most members of this genus are greyish-green, and most grow on trees. They are ubiquitous in wetter areas, where they often drape trees, hanging down from twigs and branches and waving in the wind.

Old-man’s-beard lichens often drape trees, like this Himalayan birch (Betula utilis), photographed near Pungi Tenga, Khumbu, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Old-man’s-beard lichens, waving in the wind, Ghunsa Valley, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“The Great Chief in Washington sends word that he wishes to buy our land. (…) How can you buy or sell the sky – the warmth of the land? The idea is strange to us. (…) We do not own the freshness of the air or the sparkle of the water. (…) Every part of this earth is sacred to my people. (…) When the buffaloes are all slaughtered, the wild horses all tamed, the secret corners of the forest heavy with the scent of many men, and the views of the ripe hills blotted by talking wires, where is the thicket? Gone. Where is the eagle? Gone.”

Part of a speech, allegedly given to the American President, in 1854, by Duwamish chief Si’ahl (Sealth, or Seattle) (c. 1786-1866). There is a great deal of controversy surrounding this speech, and many scholars question the authenticity of it. To me, however, it is not so important who gave the speech – under all circumstances it is of great poetic beauty.

Landscape Arch is a natural bridge in Arches National Park, Utah. That these bridges exist is due to thick layers of salt, deep in the underground. These layers are unstable because of the tremendous weight of sediments resting on them. The layers sometimes move, causing the rocks in the overlaying sediments to crack, often along parallel lines. In these cracks, alternating temperatures loosen small bits of rock, which are removed by rain and wind. In some places, underlying, softer sediments are eroded away, leaving natural bridges of harder material.

The slender and fragile Landscape Arch may fall anytime. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Our sun has become cold,

We are at the mercy of winter

And dark days.

But now the decline has come to an end

And there is a gleam of hope,

Yes, a gleam of hope,

Because the sun has turned,

And now the light and the long days are returning.

Johannes V. Jensen (1873-1950), Danish writer, in his poem Solhvervssang (’Solstice Song’), 1917.

Mute swans (Cygnus olor) resting on ice, waiting for milder weather, Roskilde Fjord, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“The woodchuck (Arctomys monax) of the bleak mountains is a very different sort of mountaineer – the most bovine of rodents, a heavy eater, fat, aldermanic in bulk and fairly bloated, in his high pastures, like a cow in a clover field. One woodchuck would outweigh a hundred chipmunks, and yet he is by no means a dull animal. In the midst of what we regard as storm-beaten desolation he pipes and whistles right cheerily, and enjoys long life in his skyland homes.”

John Muir (1838-1914), Scottish-American writer and environmentalist, in his book My First Summer in the Sierra, 1911.

In the days of John Muir, it seems, the highland marmot, or woodchuck, was regarded as the same species as the lowland woodchuck, or groundhog, Arctomys monax, now named Marmota monax. Today, however, the highland marmot is regarded as a separate species, the yellow-bellied marmot (Marmota flaviventris). This species and other marmots are described on the page Animals – Mammals: Squirrels.

Yellow-bellied marmot, resting on a rock, Sequoia National Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sitting Alone on Jingting Mountain

衆鳥高飛盡

孤雲獨去閒

相看兩不厭

只有敬亭山

This poem has been translated in various ways. One version is given below.

Bird flocks vanish into the sky.

A lone cloud calmly drifts on.

We never tire of looking at each other,

Jingting Mountain and I.

Chinese poet Li Bai (Li Bo) (701-762).

Evening light on Merra Peak (6344 m), Upper Ghunsa Valley, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“By this time, the sun was driving broad golden spokes through the lower branches of the mango trees; the parakeets and doves were coming home in their hundreds; the chattering, grey-backed Seven Sisters, talking over the day’s adventures, walked back and forth in twos and threes almost under the feet of the travelers; and shufflings and scufflings in the branches showed that the fruit bats were ready to go out on their night-picket. Swiftly the light gathered itself together, painted for an instant the faces and the cart-wheels and the bullocks’ horns as red as blood. Then the night fell, changing the touch of the air, drawing a low, even haze, like a gossamer veil of blue, across the face of the country and bringing out, keen and distinct, the smell of wood-smoke and cattle and the good scent of chapaties, baked on ashes. The evening patrol hurried out of the police station with important coughings and reiterated orders; and a live charcoal ball in the cup of a wayside carter’s hookah glowed red while Kim’s eye mechanically watched the last flicker of the sun on the brass tweezers.”

Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936), English writer, in his novel Kim, 1901.

Ox-cart and evening shadows, southern Pakistan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Jungle babbler (Turdoides striata), enjoying the evening sun in Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan, India. This gregarious species forages in family groups of six to ten birds, a habit which has given rise to the popular name ‘Seven Sisters.’ (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“So many things die in Africa, and many more shall die. But not everything should become deserts, farms, villages, cities, and empty, dry savannas. In at least one small area the world should remain as wonderful as it was created, so that black and white people can fold their hands here in silent worship. Serengeti shall not die.”

Bernhard Grzimek (1909-1987), German zoologist and environmentalist, in his and his son Michael Grzimek’s book Serengeti Shall Not Die, 1960.

Rain, falling on rocky outcrops, named Simba Kopjes, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

During their annual migration, white-bearded wildebeests (Connochaetes mearnsi) and plains zebras (Equus quagga ssp. boehmi) quench their thirst in the Grumeti River, Serengeti National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Now the elder spreads its cool hands towards the summer moon.”

Johannes V. Jensen (1873-1950), danish author, in his poem Envoi, 1921.

The role of elder (Sambucus nigra) in folklore and traditional medisine is described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Elder inflorescence, Roskilde Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Kunwar Singh was by caste a Thakur, and the headman of Chandni Chauk village. (…) What endeared him to me was the fact that he was the best and the most successful poacher in Kaladhungi, and a devoted admirer of my eldest brother Tom, my boyhood’s hero.

(…) It was now Tom’s turn to shoot, and to shoot in a hurry, for the pigs were fast approaching the tree jungle, and getting out of range. Standing four-square, Tom raised his rifle, and as the two shots rang out, the pigs, both shot through the head, went over like rabbits. Kunwar Singh’s recital of this event invariably ended up with: ‘And then I turned to Budhoo, that city-bred son of a low-caste man, the smell of whose oiled hair offended me, and said, “Did you see that, you, who boasted that your sahib would teach mine how to shoot? Had my sahib wanted to blacken the face of yours he would not have used two bullets, but would have killed both pigs with one”.’ Just how this feat could have been accomplished, Kunwar Singh never told me, and I never asked, for my faith in my hero was so great that I never for one moment doubted that, if he had wished, he could have killed both pigs with one bullet.”

Jim Corbett (1875-1955), British author, hunter, and conservationist, in his book My India, 1952.

“The pigs were fast approaching the tree jungle, and getting out of range.” – Wild boar (Sus scrofa), Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leaf’s a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.

Robert Frost (1874-1963), American poet, in his poem Nothing gold can stay, 1923.

Flowers and new leaves of field maple (Acer campestre), Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“When we hear his call [the crane] we hear no mere bird. We hear the trumpet in the orchestra of evolution. He is the symbol of our untamable past, of that incredible sweep of millennia which underlies and conditions the daily affairs of birds and men.”

Aldo Leopold (1887-1948), American writer and environmentalist, in his book Marshland Elegy, 1937.

The sandhill crane (Grus canadensis) is described on the page Animals – Birds: Sandhill cranes are a threat to breeding birds.

Cranes often call simultaneously, here Eurasian cranes (Grus grus) at Lake Hornborgasjön, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

During their spring migration in March-April, about half a million sandhill cranes – c. 80% of the total population – spend the night on sand bars in the Platte River, Nebraska. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach.”

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862), American writer, in his book Walden, 1854.

The ‘woods’, however, were not just any wood. In his book A Walk in the Woods (1998), American author Bill Bryson writes: “The inestimably priggish and tiresome Thoreau thought that nature was splendid, splendid indeed, as long as he could stroll to town for cakes and barley wine, but when he experienced real wilderness, on a visit to Katahdin [a mountain in Maine] in 1846, he was unnerved to the core. This wasn’t the tame world of overgrown orchards and sun-dappled paths that passed for wilderness in suburban Concord, Massachusetts, but a forbidding, oppressive, primeval country that was “grim and wild … savage and dreary,” fit only for “men nearer of kin to the rocks and wild animals as we.”

I guess the term “as we” indicates ‘civilized’ people like Thoreau himself.

Light and friendly forest: hardwood forest in April, Clement Farm Conservation Area, Haverhill, Massachusetts, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Grim and wild, savage and dreary” coniferous forest, Hoh Forest, Olympic National Park, Washington State, with moss-covered western hemlocks (Tsuga heterophylla), growing in a row on a fallen log, a so-called nursery log, on which they have found sufficient light to sprout. The fern on the forest floor is western sword fern (Polystichum munitum). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“The mountains are enormous stones, cast by the gods of the Underworld into the garden of the Earth. The protective gods, however, do not allow them on flat surfaces.”

Archimedes (c. 287-212 B.C.), Greek scientist.

Sunrise behind Machhapuchhare (6993 m), Annapurna, C Nepal. in Nepali, the name of this mountain means ‘fishtail’ – thus named because of its twin peaks, which are connected by a curved ridge. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Yellow butterflies

Over the blossoming virgin corn

With pollen-spotted faces

Chase one another in the brilliant breeze.

(…)

Over your fields of growing corn,

All day shall hang the thundercloud.

Over your field of growing beans

All day shall come the blessed rain!

Hopi song.

Needles of pitch pine (Pinus rigida) with raindrops, Pine Barrens, New Jersey, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Natural beauty of a country is a national treasure, from which generation after generation shall benefit through centuries. One single generation can destroy it; not dozens of generations can restore it.”

Carl Wesenberg-Lund (1867-1955), Danish zoologist, in his book Bondelandets Fauna (’Farmland Fauna’), 1927.

Fortunately, conditions are not quite as bad, as Wesenberg-Lund predicted. In later years, in Denmark and other countries, a number of drained lakes and other wetlands have been restored, which today harbour a rich wildlife.

Lake Selsø, Zealand, Denmark, was re-established in 1996. This picture shows a view over this lake from Selsø Church, with blooming marsh-marigold (Caltha palustris), greylag geese (Anser anser), and ducks. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

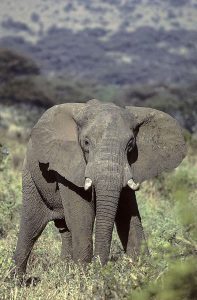

“Indeed, I think that anyone not fond of elephants cannot be of sound mind.”

Peter Matthiessen (1927-2014), American writer and environmentalist, in his book Sand Rivers, 1981.

The sad fate of elephants is described on the page Animals – Mammals: Rise and fall of the mighty elephants.

This bull savanna elephant (Loxodonta africana) in Tarangire National Park, Tanzania, is waving his ears, indicating his annoyance with the presence of our vehicle. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Asian elephant cow (Elephas maximus) with a small calf in a breeding centre near Chitwan National Park, southern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“The owls appeared now, drifting from tree to tree as silently as flakes of soot, hooting in astonishment as the moon rose higher and higher, turning to pink, then gold, and finally riding in a nest of stars, like a silver bubble.”

Gerald Durrell (1925-1995), British writer and environmentalist, in his book My Family and Other Animals, 1956.

Full Moon and grazing cattle, western Nebraska, United States. The picture has not been manipulated. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

His legs are like pillars of marble,

Set in sockets of finest gold.

His posture is stately,

Like the noble cedars of Mount Lebanon.

Song of Solomon, 5:15.

Lebanon cedars (Cedrus libani), near Ermenek, Toros Dağlari (Taurus Mountains), Turkey. This tree is native to the eastern Mediterranean, found in Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, and Cyprus. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“The concept of conservation is a far truer sign of civilization than that spoilation of a continent which we once confused with progress.”

Peter Matthiessen (1927-2014), American writer and environmentalist, in his book Wildlife in America, 1959.

Delicate Arch, in Arches National Park, Utah, is balancing precariously on the edge of an abyss, looking as if might fall any moment. In the background the La Sal Mountains. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Just living is not enough… one must have sunshine, freedom, and a little flower.”

Hans Christian Andersen (1805-1875), Danish poet.

This little boy is blowing seeds off a dandelion (Taraxacum vulgare), Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Deep Peace of the running wave to you

Deep Peace of the flowing air to you

Deep Peace of the shining stars to you

Deep Peace of the quiet earth to you.

Adapted from Gaelic runes.

Fallow field with thousands of common catchfly (Viscaria vulgaris), Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Nature manages growth and expansion in the most ideal way – and, furthermore, a divine way!”

Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), Swedish naturalist.

Crescent-leaved sundew (Drosera peltata), heavy with monsoon rain, Langtang National Park, central Nepal. This species is distributed in montane areas, from the western Himalaya across Southeast Asia to Australia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“And bending across the path as if saying prayers to welcome the dawn, were long grasses which were completely overpowered by the thick dew.”

Grace Ogot (1930-2015), born Grace Emily Akinyi, Kenyan writer and politician, in her book Land without Thunder: Short Stories, 1968.

Morning dew in grass, Corbett National Park, Uttarakhand, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“The crown of the tree had broken off sometime in the previous century, and the mossy, stout cylinder of it lay remnant on the ground nearby, slowly melting into the dirt, so soft with rot that you could have kicked it apart like an old dung pile and watched the hister beetles scuttle away.”

American author Charles Frazier (born 1950), in his excellent novel Cold Mountain, 1997.

”(…) so soft with rot…” – Moss-covered trunk, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“(…) it is a beautiful bush, whose white cotton wads, especially against the light, brighten the brownish and somewhat autumn-dark fen.”

Gunnar Brusewitz (1924-2004), Swedish artist and writer, in his book Strandspegling. Naturupplevelser i tid och rum (‘Coastal reflections. Nature experiences in time and space’), 1979, about the bay willow (Salix pentandra), which, as opposed to most other willows, spreads its seeds late in the autumn.

In this picture from Jutland, Denmark, seeds of bay willow are sailing into the wind. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Down in the valley a couple of lions are roaring, and the bullfrogs are serenading, accompanied by the cicadas’ finely tuned violins.”

Bror Blixen (1886-1946), Swedish playboy and big-game hunter.

Golden cat in golden grass. – Male lion (Panthera leo), Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Other quotes on nature may be found on the page Folly of Man.

(Uploaded April 2016)

(Latest update February 2025)