Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Among Annapurna giants

In the centre of the Annapurna Range is an alpine valley, surrounded by a circle of tall mountains, among these Annapurna I (8091 m), Gangapurna (7454 m), Glacier Dome (7193 m), Annapurna South (7219 m), Hiunchuli (6441 m), and Machhapuchhare (6993 m). The latter peak is sacred to Hindus and may not be scaled. In Nepali, Machhapuchhare means ‘fishtail’ – a name given to this mountain in allusion to its twin peaks, which are combined by a curved ridge.

This valley is usually called Annapurna Sanctuary, although, strictly speaking, it is not a sanctuary. The valley, however, does constitute a part of the huge Annapurna Conservation Area, covering 7,629 km2, in which authorities and NGO’s strive to make the locals utilize the area in a sustainable way. One result of their efforts is that hunting has largely ceased, for which reason the wildlife here is rich and varied. Conserving the forests is more difficult. The numerous small hotels in the area are urged to utilize solar heating or hydro-electricity, when heating up water, and to use kerosene when cooking, but during periods of political instability, the import of kerosene from India often comes to a halt, forcing the locals to cut trees for firewood.

Annapurna Sanctuary is drained by a single river, the Modi Khola, running north-south, roaring down a deep gorge between the peaks of Machhapuchhare and Hiunchuli. Over a stretch of only c. 50 km, this river passes through five vegetation zones, from alpine to almost tropical, before joining the larger Kali Gandaki River.

Most of the plant species mentioned below are dealt with in detail on the pages Plants: Himalayan flora 1, 2, and 3.

In May, the hot air vibrates, and from groves of trees a deafening chorus of cicadas make a racket, mingled with the monotonous duet calls from a pair of great Himalayan barbets (Psilopogon virens) and the four-toned call of the Indian cuckoo (Cuculus micropterus). Nepalese people render the call of the cuckoo as kafal pako, meaning ’the kafal fruit is ripe’ – which is the case in May, when the call is at its peak. When the British arrived in India, they rendered the call as One more bot-tel! – very suitable at this time of the year, when the heat is indeed intense!

In this densely populated area, most of the forest has been cleared to construct terraced fields, but to fulfil people’s need for firewood and timber, plantations of chir pine (Pinus roxburghii) have been established. The needles of this species, which are arranged in groups of 3, can grow to 38 cm long – much longer than those of the blue pine (Pinus wallichiana), which grows at higher altitudes.

Schima wallichii, of the tea family, is also widely planted. In Nepali, this species is called chilaune (’to itch’). Beneath the bark, mature trees have a layer of hairs that irritate the skin. The toxic bark can be used when fishing. It is chopped up and sprinkled into the water, anaesthetizing the fish, which float to the surface.

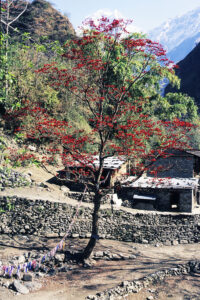

Near villages, you often see a species of coral tree, Erythrina stricta, of the huge pea family (Fabaceae), which, in March-April, displays a profusion of coral-red flowers. Various birds feed in these flowers, such as jungle myna (Acridotheres fuscus), red-whiskered bulbul (Pycnonotus jocosus), black drongo (Dicrurus macrocercus), and ring-necked parakeet (Psittacula krameri).

The most popular chotara trees are two species of fig, banyan (Ficus benghalensis), or Bengal fig, which often has numerous aerial roots hanging down from its branches, and pipal (Ficus religiosa), the leaves of which are heart-shaped and long-pointed. These two species are often planted side by side, and according to a local Nepalese legend they are husband and wife. The small fruits of these fig trees are an important food item for many bird species, including red-billed blue magpie (Urocissa erythrorhyncha) and blue-throated barbet (Psilopogon asiaticus).

The Buddha obtained nirvana beneath a pipal tree, and for this reason Buddhists named it Bodhi (’Tree of Enlightenment’). The Bodhi tree is dealt with in detail on the page Plants: Pipal and banyan – two sacred fig trees, whereas The Buddha and Buddhism are described in depth on the page Religion: Buddhism.

Other species are also planted as chotara trees, one being bel (Aegle marmelos), of the citrus family (Rutaceae). Its large fruits are edible, and they are also utilized as traditional medicine for treatment of certain ailments, including diarrhoea and dysentery, while an extract from its root and bark is used for fever. Various items are made from the very hard wood, including wheel hubs. This plant is sacred to Hindus, and its leaves are often presented as an offering to the mighty god Shiva.

A very strange custom, which used to be common among the Newar people of Nepal, is the ‘marriage’ of little girls to a fruit from the bel tree. This fruit is regarded as a symbol of Shiva’s son Kumar, and the ‘marriage’ ceremony is similar to a genuine marriage. This marriage cannot be annulled, but it doesn’t prevent the girl from marrying a genuine man. The original reason for this remarkable custom was that, according to ancient Hindu tradition, a widow was supposed to commit suicide in a terrible ritual, sati, during which she would throw herself into her husband’s funeral pyre. A Newar widow, however, did not have to perform this act, as her first husband, Kumar-bel, was still alive!

Other chotara species include rose apple (Eugenia jambos), a tree of the myrtle family (Myrtaceae), locally called jamun. On its shiny leaves are numerous transparent dots, causing locals to use them as a remedy for spotty skin – an excellent example of the Doctrine of Signatures, whose followers claim that the Great God made all plants, so that humans would recognize the usage of them. Its fruit is an edible berry.

Another one is the butter tree (Diploknema butyracea), of the family Sapotaceae, from whose seeds a butter-like product can be extracted, called chiuri ghee. The well-known mango tree (Mangifera indica), with its delicious fruits, is also sometimes planted as chotara tree.

Senna occidentalis (also called Cassia occidentalis), of the sub-family Caesalpinioideae, has beautiful yellow flowers, whereas Callicarpa macrophylla, of the mint family (Lamiaceae), has large clusters of small, violet flowers. – A picture of Callicarpa may be seen on the page Plant hunting in the Himalaya: Rainy season in Nepal.

Members of the genera Melastoma and Osbeckia, of the melastoma family, with two and seven Himalayan species, respectively, all have showy reddish-violet flowers. Spanish flag (Lantana camara) was introduced as an ornamental from America, but has become a serious pest in many lower valleys of the Himalaya, as it is able to form large, impenetrable scrubs, expelling native species.

Among the subtropical herbs, members of the acanthus family (Acanthaceae) are conspicuous, comprising at least 28 genera. Among encountered species were the ubiquitous Barleria cristata, Justicia adhatoda, and Asystasia macrocarpa. Many genera of the nettle family (Urticaceae) are also found. Besides the Himalayan nettle (Urtica ardens), which is quite similar to the European common nettle (U. dioica), you often encounter Girardinia diversifolia, which you will quickly learn to avoid, as it has a very powerful sting. The leaf shape of this species is quite variable, but mostly it has three large lobes. Wet rocks are often covered in Pilea umbrosa or Elatostema sessile, both belonging to the same family, but without stinging hairs.

Cleared areas, which lie fallow, are often invaded by a large fern, Diplopterygium giganteum (formerly called Gleichenia gigantea), which forms large growths. Various weeds grow along the edge of terraced fields, including a reddish-brown composite, Crassocephalum crepidioides, a tiny St. John’s-wort, Hypericum japonicum, a low, creeping knotweed with globular inflorescences, Polygonum capitata, and the invasive goat-weed (Ageratum conyzoides), which is dealt with in depth on the page Nature: Invasive species.

Branches of larger trees are often covered in epiphytes, such as lichens, mosses, ferns, a mistletoe, Viscum articulatum, and orchids of the genera Coelogyne and Dendrobium, comprising 12 and c. 26 species, respectively, in the Himalaya. The commonest species are Coelogyne nitida, Coelogyne cristata, and Dendrobium amoenum, all of which flower between March and May. Rhaphidophora decursiva, a large, philodendron-like liana, is very common, climbing up tree trunks by means of suckers.

On the forest floor are shrubs like Dichroa febrifuga, of the hydrangea family, the bark of which is used as a febrifuge, Mussaenda roxburghii, of the coffee family, which is easily identified by its white bracts, surrounding the orange inflorescences, and Mahonia napaulensis, of the barberry family, with large, beautiful, yellow inflorescences. Herbs include Arisaema tortuosum and A. erubescens, peculiar plants of the arum family.

Birdlife at this altitude is abundant. Black-capped sibia (Heterophasia capistrata) is very common. Previously, this bird was placed in the timaliid family (Timaliidae), but has now been moved to the newly established laughingthrush family (Leiothrichidae).

Other birds include the gorgeous maroon oriole (Oriolus traillii), and in the river the brown dipper (Cinclus pallasii), which, unlike the European dipper (C. cinclus), is of a uniform brown colour.

Many herbs grow on wet rocks along the streams, including Platystemma violoides, of the gloxinia family (Gesneriaceae), and two primroses, the violet Primula edgeworthii and the red P. geraniifolia. In cracks on sun-exposed rocks, grasses and various herbs have taken root, such as the pink Roscoea purpurea, of the ginger family, a large-leaved buttercup, Ranunculus diffusus, and hairy bergenia (Bergenia ciliata), of the saxifrage family. Blue-grey Kashmir rock agamas (Laudakia tuberculata), with numerous yellow dots on the body, often scuttle about on the rocks.

At an altitude of c. 2,800 m, the forest floor is often covered in dense growths of various species of dwarf bamboo, among others the genera Arundinaria and Thamnocalamus. Bamboo is utilized in numerous ways in the Himalaya. Baskets and mats are woven from split stems of dwarf bamboo, while the larger species are used for house construction, bridges, scaffolds, etc. The thickest stems can be used as water pipes, after removing the node walls.

Various bushes also grow here, including a bramble with rose-red flowers, Rubus foliolosus, a yellow jasmine, Jasminum humile, and a currant with black berries, Ribes himalense. In clearings, I observe an orchid with violet-red flowers, Dactylorhiza hatagirea, a near relative of the European early marsh orchid (D. incarnata). Its tubers are much utilized in traditional medicine, and it has now become scarce due to over-collecting.

Outside the summer months, fresh vegetables are often difficult to find in rural areas of the Himalaya. A widespread method of obtaining nutrients from vegetables at times, when fresh ones are not available, is to make gundruk – fermented leaves of certain cultivated plants, including cabbage, mustard, and radish, and of various wild plants, such as Arisaema utile, a buttercup, Ranunculus diffusus, and Nepalese dock (Rumex nepalensis).

Two methods are utilized to make gundruk. One is to wash the leaves and leave them to dry for a day, after which the last juice is beaten out of them. They are then stuffed firmly into a container, which is tightly closed, making it airtight. About a week later, the fermented leaves are taken out and left to dry in the sun, after which they are stored in a dry place for later use. Another method is to boil the leaves for a short time and then stuff them tightly in a container. After a short period of time, the juice is removed and boiling water added. The leaves are then left to ferment for 4-5 days, before being dried in the sun. (Source: N.P. Manandhar. Plants and People of Nepal)

Gundruk can be kept for about a year. The fermented leaves emit a characteristic fragrance, and they have a unique, strong, and lovely taste – at least in my opinion.

In clearings, you encounter a profusion of herbs, including Anemone obtusiloba, which has white or blue flowers, and the yellow Megacarpaea polyandra, of the mustard family (Brassicaceae), which can grow taller than a man. On a wet rock, I observe the rare Pycnoplinthopsis bhutanica, likewise of the mustard family. With its low growth and thick leaf rosette, it somewhat resembles a primrose.

Around 3,700 m, trees become scarce, and woody plants are mainly composed of huge thickets of various dwarf shrubs, mainly Rhododendron anthopogon and R. lepidotum, a honeysuckle, Lonicera obovata, and various species of Cotoneaster. Various herbs grow in clearings among the bushes, such as a beautiful fritillary, Fritillaria cirrhosa, Arisaema propinquum, an alp lily, Gagea longiscapa (formerly called Lloydia longiscapa), and an imposing yellow primrose, Primula sikkimensis, which can grow to 90 cm tall.

In May, few plants are flowering at this altitude. However, a pinkish-violet primrose, Primula denticulata, is abundant. The primrose genus probably evolved in the Himalaya, and at least 62 species are found here. Pictures of many other primroses may be seen on the page Plants: Primroses.

Other plants include a white, cushion-forming saxifrage, Saxifraga andersonii, and a cinquefoil, Potentilla argyrophylla, which occurs in several colour varieties: purplish, red, orange, and yellow.

At this altitude, the commonest bird is the yellow-billed chough (Pyrrhocorax graculus). Otherwise, animal life is scarce in the valley at this time of the year. However, while I am resting near a small stream, a Siberian weasel (Mustela sibirica) comes tearing along the bank, stops for a few seconds to investigate me, and then disappears like lightning.