Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Plants in folklore and poetry

Sage was a healing herb, supposed to impart wisdom and immortality, rosemary is for remembrance, and was believed to identify one’s true love, whereas thyme was believed to impart courage.

It has been proposed that ‘rosemary and thyme’ is a misheard lyric for ‘grows merry in time’.

Traditionally, fungi and lichens were regarded as belonging to the plant kingdom, but have now been placed in a separate kingdom. As most people still regard them as plants, I include a few at the bottom of the page.

In case you find errors on this page, I would be grateful to hear about them. You can use this email address: respectnature108@gmail.com.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kelos (‘burnt’ or ‘dry’), referring to the burnt appearance of the flowers of some species.

Some varieties are cultivated as ornamentals, including cristata, known as crested cockscomb. In several Asian and African countries, tender parts are eaten as a vegetable. The plant is also used for fodder, and in soap. In several African countries, it is utilized to help control growth of the parasitic witchweed (Striga), which is a pest in cereal crops. (A picture, depicting Striga asiatica, is shown on the page Plants: Parasitic plants.)

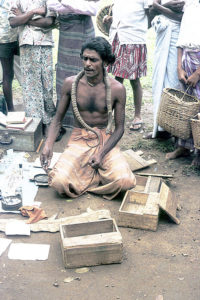

Flowers and seeds have antibacterial properties. They are utilized in treatment of bloody stool, haemorrhoids, bleeding from uterus, leucorrhoea, fever, dysentery, jaundice, and diarrhoea. Seeds are also used for various eye diseases. Powdered seeds are regarded as an aphrodisiac. The root is used for colic, gonorrhea, and eczema. A poultice of the stem and leaves are applied to wounds, inflamed areas, and skin problems. In Sri Lanka, the leaves are used for inflammations, fever, and itching, the seeds for fever and mouth ulcers. In China, flowers and seeds are used for gastroenteritis and leucorrhoea. This species is a very effective remedy against the parasite Trichomonas vaginalis, which causes infection of the genitals. It is also used as an antidote for snake poison.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘silvery’, alluding to the shiny white bracts in the inflorescence (see pictures).

The inflorescence of these plants is very distinctive, consisting of a compact globular umbel on an unbranched stem. Initially, the umbel is enclosed in a papery spathe, which splits into lobes, when the stalked flowers unfold.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of garlic (below).

Today, it is highly valued for its antifungal, antiseptic, and antibacterial properties, utilized for a huge number of ailments, including heart trouble, high or low blood pressure, high level of cholesterol, hardening of arteries, enlarged prostate, fever, headache, stomach ache, gout, joint pain, haemorrhoids, and menstrual disorders. Garlic is excellent for respiratory infections, such as colds, cough, asthma, and bronchitis, and it is highly probable that it acts as a preventive for many types of cancer.

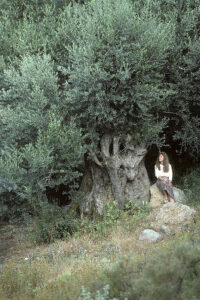

In Europe, in the old days, garlic was regarded as a magic herb, which would protect you against evil. The Ancient Greeks often placed it at crossroads to placate the frightening Hecate, goddess of the underworld, who haunted desolate places at night. People of the Balkans would hang garlic on stable doors to deter milk thieves at night, and in other parts of Europe, garlic rosaries were worn around the neck as protection from evil spirits and disease. In the novel Dracula (1897), by Irish author Abraham Stoker (1847-1912), garlic is utilized to ward off vampires.

Some of the Ancients also believed that garlic was toxic. In his Book of the Epodes, Roman poet Quintus Horatius Flaccus (65-8 B.C.), also known as Horace, says: “If any person at any time with an impious hand has broken his aged father’s neck, let him eat garlic, more baneful than hemlock. Oh! the hardy bowels of the mowers! What poison is this that rages in my entrails? Has viper’s blood, infused in these herbs, deceived me?”

Danish herbalist Simon Paulli (1603-1680) says: ”It is well-known that among animals cocks are the most belligerent, which caused Artemidorus [Artemidorus Daldianus, also known as Artemidorus Ephesius, Greek astrologist and philosopher from the 2nd Century A.D.] to say: ”Cocks are really belligerent and inclined to quarrel and brawl.” However, as many people may know, if you want them to live in all friendliness, you must feed them garlic.”

According to a Hindu legend, The Churning of the Milk Ocean, from the Bhagavata-Purana, garlic came into existence in this way:

The gods had become weakened and had been usurped by the asuras (demons). The gods appealed to the supreme god Vishnu for help, and he suggested that they should regain their power by drinking the miraculous amrita, the nectar of immortality, which they could obtain by churning the cosmic milk ocean, thus bringing the jar with amrita to the surface. However, Vishnu advised the other gods to treat the asuras diplomatically by suggesting them to jointly churn the ocean. When the amrita was brought to the surface, Vishnu would ensure that the gods got hold of it. To perform this stupendous task, the gods and the asuras uprooted the mountain Mandara, placing it upside down in the ocean, and coiling the giant, many-headed naga (serpent) Vasuki around it. By pulling alternately at each end of Vasuki, the mountain would act as a gigantic churn, thus bringing the pot, containing the amrita, to the surface. When that happened, the man-eagle Garuda, Vishnu’s mount, snatched the pot and ran away with it, but some drops spilled and fell on the ground. Later a plant, containing all the divine properties of the amrita, sprouted from these drops – garlic.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘sown’ or ‘planted’, alluding to its cultivation for thousands of years.

The round, hollow leaves are used as a flavouring herb, especially with cheese and fish dishes, for instance as an ingredient in the gräddfil (sour cream) sauce, served with the traditional herring dish at the Swedish midsummer celebration.

In his book Försök til en flora oeconomica Sveciæ eller Swenska wäxters nytta och skada i hushållningen (‘Attempt at a Flora. Benefits and harms of Swedish plants in households’), from 1806, Swedish author Anders Jahan Retzius (1742-1821) mentions that chives is used with pancakes, soups, fish, and sandwiches. In Poland and Germany, it is served with quark (a creamy cheese).

The leaves and the edible flowers are used in salads, and the flowers are added to vinegar.

Retzius (above) describes how Swedish farmers would plant chives between rocks to make borders of their flowerbeds, as it would repel insect pests. Juice from the leaves can be used for the same purpose, as well as fighting fungal infections, mildew, and potato scab.

According to the Ancient Romans, chives could relieve the pain from sunburn or a sore throat, and eating it could increase blood pressure and act as a diuretic.

In his Epigrams, Iberian-Roman poet Marcus Valerius Martialis (c. 40-100 A.D.), in English known as Martial, writes the following about chives: “He who bears chives on his breath, is safe from being kissed to death.”

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek skhoinos (‘rush’, genus Juncus) and prason ‘leek’, thus ‘rush-like leek’, naturally referring to the rush-like shape of the leaves.

The specific name stems from a Medieval German name of the species, Siegwurz (‘root of victory’). Another old German name was Allemannsharnish (’all people’s armour’), referring to the onion, which is wrapped in a thick layer of bracts. In the Middle Ages, this layer was likened to an armour. Alpine leek was carried by soldiers as an amulet, as it was believed that it would protect the bearer from being wounded.

In his illustrated herbal Neuwe Kreuterbuch (from 1588), German physician and botanist Jakob Dietrich (1525-1590), also called Jacobus Theodorus, but better known under the name Tabernaemontanus, remarks that Alpine leek protects from “all kinds of ghosts and bad spirits.” He continues: “Farmers and herdsmen praises it highly as a protection against all kinds of bad air and vapours.”

The plant was also utilized by Bohemian mine workers as a charm against ‘unclean spirits’.

When building a stable in Vorarlberg, western Austria, a cavity was drilled in the lowest beam, and a bulb of alpine leek was placed in it, which would protect the cattle against being bewitched.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek gala (‘milk’) and anthos (‘flower’), referring to the white flowers of the genus.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘of the snow’, derived from nix (‘snow’). It refers to the early flowering of the plant.

The name snowdrop first appeared in 1633 in the book Great Herball, written by English herbalist John Gerard (c. 1545-1612). In the first edition of his book, Gerard had named it the timely flowring bulbus violet. The word snowdrop may be a translation of the German word Schneetropfen – a type of earring, which was popular in those days. Other common English names include February fairmaids, dingle-dangle, Candlemas bells, Mary’s tapers, and, in Yorkshire, snow piercers. (Sources: M. Bishop, A. Davis & J. Grimshaw (2002), Snowdrops: A Monograph of Cultivated Galanthus. Griffin Press, and R. Mabey (1996), Flora Britannica. Sinclair-Stevenson)

The name Candlemas bells refers to the Christian feast day Candlemas, on 2nd of February, also known as the Feast of the Presentation of Jesus Christ, which commemorates the presentation of Jesus at the temple by Joseph and Mary (Luke 2:22-40). Naturally, the first part of the name alludes to the early flowering of snowdrop, the last part to the flower shape.

The name Mary’s tapers (‘taper’ is an old word for ‘candle’) probably refers to the white colour and the longish shape of the flowers.

An old legend relates that when Adam and Eve were expelled from the Garden of Eden, they experienced dark and cold for the first time, and Eve sat down on the cold ground and wept. An angel appeared before her, caught a snow flake in his hand and blew on it. The water drop fell to the ground, and a snowdrop appeared. This gave comfort to Eve, who began to have new hope.

The family name is derived from the name of honey bees, genus Apis, referring to the fact that many plants of the family are much visited by bees and other nectar-sucking insects, in particular hovering flies.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of dill.

It is widely used in European and Asian cuisines as a vegetable, in soups, sauces, and cakes, and as topping on cold dishes and sour cream products. The seeds are used as a spice, especially in pickles and vinegar. In Jutland, Denmark, dill, thyme, and bog myrtle were once added to a local liqueur. It is also utilized as perfume in soap production, and has been used as an insect repellent.

In the Middle Ages, dill was used by magicians in their spells, and in charms against witchcraft. In Nimphidia, the Court of Faery, from 1627, English poet Michael Drayton (1563-1631) writes:

In his book The Popular Names of British Plants, Richard Chandler Prior (1809-1902) states that the name dill is derived from an old Norse word, dilla (‘to lull’), in allusion to the carminative properties of the plant. The strange name meeting house seed refers to the former custom of chewing dill seeds during long church services to calm rumbling stomachs.

The medical properties of dill were already known in Ancient Greece and Rome, and it is also mentioned in the Bible.

In his Complete Herbal, English herbalist Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654) writes: ”Mercury has the dominion of this plant, and therefore to be sure it strengthens the brain. (…) It stays* the hiccough, being boiled in wine, and but smelled unto, being tied in a cloth. The seed is of more use than the leaves, and more effectual to digest raw and vicious humours, and is used in medicines that serve to expel wind, and the pains proceeding therefrom.”

In today’s herbal medicine, dill is considered antibacterial, an antioxidant, and a powerful remedy for menstrual flow. The fruits, as well as an oil derived from them, possess stimulant, aromatic, carminative, and stomachic properties. It is utilized for lowering cholesterol levels, and for colic, excessive gas, bad breath, heartburn, menstrual cramps, depression, and epilepsy. In Chinese traditional medicine, it is said to benefit the spleen, kidney, and stomach.

The specific name is Latin, derived from gravis (‘heavy’) and olens (‘fragrant’).

The generic name is explained below.

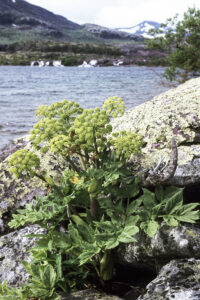

Garden angelica has been utilized medicinally for hundreds of years. In the Middle Ages, dried roots were considered to be an important remedy against plague. In his Paradise in Sole, from 1629, herbalist John Parkinson (1567-1650) puts angelica in the forefront of all medicinal plants.

The root stalks, leaves and fruit possess carminative, stimulant, diaphoretic, stomachic, tonic, and expectorant properties, and today angelica is regarded as a valuable remedy for various heart problems, heartburn, colds, coughs, fever, pleurisy, rheumatism, psoriasis, and urinary diseases. It contains an essential oil with antiseptic properties.

Middle Age legends explain the names angelica and archangelica in various ways. These words are derived from the Latin angelicus (‘angelic’), originally from Ancient Greek angelos (‘messenger’), and from Ancient Greek archos (‘leader’). One legend has it that an angel had a dream that this herb would cure the plague. Another one claims that angels – or even Archangel Gabriel himself – brought the knowledge of this herb to humans. A third legend says that it blooms on the day of Michael the Archangel (May 8, old style; May 18, new style), and on that account it is believed to protect against evil spirits and witchcraft. All parts of this species were thought to be an effective remedy against spells and enchantment, one of its popular names being Root of the Holy Ghost.

The obsolete specific name is derived from the Latin officina (‘workshop’ or ‘office’), and the suffix alis, thus ‘made in a workshop’. However, in a botanical context, the word denotes plants species that were sold in pharmacies due to their medicinal properties.

Tender stems and leaves of angelica are eaten raw or cooked, especially in the Faroe Islands and Greenland. Stem and seeds are used in confectionery, and candied stems are eaten by the French. The roots, which in autumn has a high content of sugar, are dug up and boiled. Angelica root used to be an important ingredient in chartreuse, the famous liqueur produced by Carthusian monks. The dried leaves, on account of their aroma, are used in the preparation of hop bitters.

In Chinese, the root is called 當歸 (‘female ginseng’) due to its usage as treatment of menstrual disorders. It is also utilized for other ailments, including liver problems, hair loss, sciatica, and shingles.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘of woods’. However, wild angelica is more commonly found in open areas, including forest and field edges, hedgerows, and the outskirts of marshes.

Medicinally, this plant has been used as a poorer substitute for garden angelica, utilized for a number of ailments, including lung and chest problems, rheumatism, and corns. In Ireland, chewing the roots of the plant before breakfast was said to cure heart palpitations and promote urination, and the plant was also used in treatment of epilepsy and hydrophobia.

It yields a yellow dye. In England, children once used the hollow stem as a ‘pea shooter’.

The generic name is explained below.

Originally, poison hemlock was called Cicuta in Latin and in several South European languages, but as this name was also applied to another poisonous umbellifer, the water-hemlock (Cicuta virosa), Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), decided to apply the name Conium after classical Greek name of the plant, koneion, derived from konas, to ‘whirl around’, as it causes vertigo and death when eaten. Naturally, the common names poison parsley, devil’s bread, and devil’s porridge also refer to its great toxicity.

The plant is sedative and antispasmodic, paralyzing the centres of motion. For this reason, it was recommended as an antidote to poisoning from strychnine and similar poisons. It was also prescribed for tetanus, hydrophobia, teething in children, epilepsy from dentition, cramps, etc. When inhaled, it was said to relieve cough associated with bronchitis and asthma, and also whooping-cough.

Greek physician, pharmacologist, and botanist Pedanius Dioscorides (died 90 A.D.), who was the author of De Materia Medica (five volumes dealing with herbal medicine), recommended this herb for external treatment of herpes. In the Middle Ages, hemlock was applied to cancerous tumours, and, mixed with betony and fennel seed, it was thought to cure rabies.

Formerly, poison hemlock caused several deaths, because its root was confused with the root of parsnip. In some cases, the poison was utilized to get rid of voles by soaking nuts in hemlock juice and then placing them at the entrance to their dens.

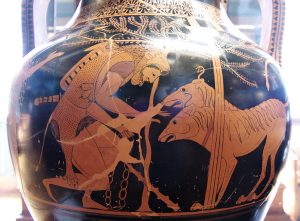

Greek philosopher Socrates (469-399 B.C.), who was accused of introducing new gods and of corrupting youth, was sentenced to commit suicide by consuming hemlock juice. His last minutes are described in Phaido, by Greek poet Plato (c. 428-348 B.C.):

”(…) returned with the jailer carrying the cup of poison. Socrates said: “You, my good friend, who are experienced in these matters, shall give me directions how I am to proceed.”

The man answered: “You have only to walk about until your legs are heavy, and then to lie down, and the poison will act.”

At the same time he handed the cup to Socrates, who in the easiest and gentlest manner, without the least fear or change of colour or feature, looking at the man with all his eyes, as his manner was, took the cup and said: “What do you say about making a libation out of this cup to any god? May I, or not?”

The man answered: “We only prepare just so much as we deem enough.”

“I understand,” he said, “but I may and must ask the gods to prosper my journey from this to the other world, even so, and so be it according to my prayer.”

Then raising the cup to his lips, quite readily and cheerfully he drank off the poison. (…) he walked about until, as he said, his legs began to fail, and then he lay on his back, according to the directions, and the man who gave him the poison now and then looked at his feet and legs; and after a while he pressed his foot hard, and asked him if he could feel. Socrates said no; and then his leg, and so upwards and upwards, and showed us that he was cold and stiff.

Socrates felt them himself, and said: “When the poison reaches the heart, that will be the end.”

He was now beginning to grow cold about the groin, when he uncovered his face, for he had covered himself up, and said his last words: “Crito, I owe a cock to Asclepius. Will you remember to pay the debt?”

In Ancient Greece, it was customary to sacrifice a cock to Asclepius, the god of medicine, when you had recovered from an illness. In this case, Socrates had left the vulnerable, sickly life and had been healed to eternity.

In an old Danish medicinal book, herbalist Henrik Harpestræng (died 1244) says: ”If a virgin applies the juice to her breasts, they will become stiff and stay thus” (i.e. they won’t grow any bigger). Furthermore, he claims that ”applied above the penis, the juice restricts the lust for women and spoils all the semen, by which a child is born.”

In another Danish herbal book, the juice is recommended for monks and nuns, as it would cause them to behave chastely. It was also recommended for mothers, when their child was to be weaned. The juice was applied to the nipples – a rather drastic method, as the child might easily be poisoned.

In his book Art of Simpling, English botanist William Coles (1626-1662), also called William Cole, writes: “If asses chance to feed much upon hemlock, they will fall so fast asleep that they will seeme to be dead, in so much that some thinking them to be dead indeed have flayed off their skins, yet after the hemlock had done operating they have stirred and wakened out of their sleep, to the griefe and amazement of the owners.”

This species is mentioned in the tragedy King Lear, by William Shakespeare (1564-1616):

The specific name maculatum means ‘spotted’, referring to the reddish spots on the stem. According to a Christian legend, these spots represent the brand, which was applied to Cain’s brow after the killing of Abel.

The common name hemlock is derived from the Anglo-Saxon words hem (‘border’ or ‘shore’) and leác (‘plant’). According to a 14th Century herbal book, there are two kinds of hemlock, one being the “grete homeloc, called kex, or wode whistle, being of no use except for poor men’s fuel, and children’s play.” The word kex may mean ‘with a hollow stem’, or it may stem from a Swedish name of the plant, käx, which possibly refers to the similarity of the umbel to a primitive basket for catching fish, called käx. Wode is Old English for ‘mad’ or ‘insane’.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek koriannon (‘stink bug’), undoubtedly referring to the very powerful fragrance of coriander (below).

All parts of the plant are edible, and the species is utilized as food over most of the world. The strongly aromatic fresh leaves are eaten as a vegetable, and the dried seeds are a very common spice, either whole or ground, especially in Indian cuisine, where it is called dhanya. It is one of the main ingredients in the popular spice mixture garam masala. The root is used in Thai cuisine.

Since 1610, Carmelite friars have been making so-called Carmelite drops, a liquor, in which coriander is one of the ingredients.

In California, aphids are a serious pest in organic lettuce fields. Experiments have shown that coriander was among the species that, when planted with lettuce and allowed to flower, would attract hoverflies, the larvae of which eat up to 150 aphids per day. (Source: E. Brennan. Efficient Intercropping for Biological Control of Aphids in Transplanted Organic Lettuce, in: articles.extension.org).

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek koriannon (‘stink bug’) – a name that was probably given because of the very powerful fragrance of this plant. The Spanish name cilantro is a corruption of Coriandrum, whereas the name Chinese parsley stems from the very popular usage of this herb in Chinese cuisine.

Coriander has been utilized medicinally for at least 3000 years. Since the Middle Ages, it was used as a digestive and for stomach trouble, including flatulence. Other ailments traditionally treated with coriander include skin inflammation, diarrhoea, high cholesterol levels, mouth ulcers, anemia, and diabetes. Alcohol, containing coriander, is rubbed on rheumatic joints and muscles.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘sown’ or ‘planted’. The Spanish name cilantro is a corruption of the generic name, whereas the name Chinese parsley stems from the very popular usage of this herb in Chinese cuisine.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek daukos, a term first applied by Greek-Roman physician, surgeon, and philosopher Aelius Galenus (c. 129-210 A.D.), also known as Claudius Galenus or Galen of Pergamon, to distinguish the carrot from the parsnip.

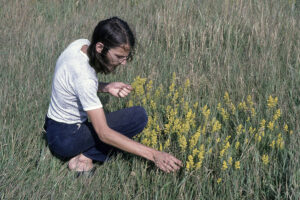

In North America and Australia, it has invaded open grasslands, meadows, roadsides, abandoned fields, waste areas, and degraded prairies, often displacing native plants. In his delightful book All about Weeds, American botanist Edwin Spencer (1881-1964) says: “(…) authorities say that it is the cultivated carrot run wild. If it is, it has run a long way and into all sorts of places. It seems never to be the least particular in its choice of a habitat. It thrives in uncultivated ground, wherever or whatever it may be, as long as it is not densely shaded.”

Some authorities claim that 13 subspecies exist, 12 wild taxa and one cultivated, named ssp. sativus. The original wild species, named ssp. carota, has a thin, white root, which has a bitter taste and is inedible. It is generally assumed that the cultivated purple form, which contains red anthocyanins, originated in Afghanistan and was later cultivated in Afghanistan, Russia, Iran, Pakistan, and Turkey. The purple carrot, together with a yellow variety, spread to the Mediterranean and Western Europe around the 11-14th Centuries, and to China, India, and Japan in the 14-17th Centuries. The orange form, which contains carotene, probably arose somewhere in Europe through gradual selection within yellow carrot populations. The Dutch types Long Orange and Horn were the basis for the orange carrot cultivars that are now grown all over the world. In Asia, they have largely replaced the purple and yellow types because of superior yield and changing fashion. (Source: cabi.org)

The specific name, derived from the classical Greek word for carrot, karoton, first appears in the writings of Greek rhetorician and grammarian Athenaeus of Naucratis (c. 170-220 A.D.). The English name evolved around 1530, derived from Middle French carotte.

The popular name bird’s-nest refers to the umbel, which, after flowering, curls upwards, forming a dense structure, which somewhat resembles a bird’s nest. The popular names bishop’s lace and Queen Anne’s lace were given in allusion to the inflorescence, which resembles lace. The Anne in question may refer to Queen Anne of Great Britain (1665-1714), or to her great grandmother, Anne of Denmark (1574-1619), who was married to King James Charles Stuart (1566-1625). In those days, lace was prominent in fine clothing.

In the centre of each inflorescence is one, or sometimes a few, red or purple flowers. According to legend, they are thought to represent a blood droplet where Queen Anne pricked herself with a needle when she was making the lace. One biological explanation is that they may attract insects. This explanation, however, is not satisfactory. Other umbellifers, which possess only white flowers, have no difficulty in attracting insects. As Spencer (above) expresses himself: “What possessed old Mother Nature to attempt to hide that purple stitch in the center of each of the Queen’s snow-white kerchiefs?”

The fruit of these plants is characteristic, strongly compressed and ribbed, the lateral ribs with a broad wing. Inside the fruit are club-shaped resin canals, clearly visible against the light.

The generic name is a Latinized version of the classical Greek name of a southern European plant, which was utilized in traditional Greek medicine. It was called panakes herakleion, meaning something like ‘the universal healing herb of Herakles’. It was thought that the immensely strong mythological hero Herakles (in Latin Hercules) discovered the medicinal properties of this plant. The generic name was applied in 1753 by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), undoubtedly referring to the profuse growth of many of these plants, likened to the strength of Herakles.

The common name hogweed is variously interpreted, either referring to pigs being fond of eating common hogweed (below), or as a derogatory term, a plant only fit for pigs. Cow-parsnip, used from about 1548, presumably alludes to the plant being eaten by cattle.

Danish herbalist Henrik Smid (c. 1495-1563) recommends the root, soaked in salt, as a diuretic, and taken with food it is a good remedy for urinary hecitancy. Other Middle Age herbalists used the boiled root in a poultice, especially for treatment of enlarged liver, spleen, and uterus.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek spondylos (‘vertebrate’), alluding to the segmented stem.

In the 1800s, it was introduced as an ornamental to Europe, and later to the United States and Canada. It has become naturalized in many areas, especially wetlands, and due to its vigorous growth it often expels native species. Furthermore, its sap is toxic to the human skin, causing inflammation and blisters. In many countries, its spreading is inhibited by using herbicides – the only known efficient means to control this species.

The specific name honours Italian neurologist, physiologist, and anthropologist Paolo Mantegazza (1831-1910), who was known for his investigation of coca leaves and their effects on the human psyche. He tested the leaves on himself in 1859, and then wrote a paper, titled Sulle Virtù Igieniche e Medicinali della Coca e sugli Alimenti Nervosi in Generale (“On the hygienic and medicinal properties of coca and on nervous nourishment in general”). He noted enthusiastically the powerful effect of the cocaine in the leaves:

“(…) I sneered at the poor mortals condemned to live in this valley of tears while I, carried on the wings of two leaves of coca, went flying through the spaces of 77,438 words, each more splendid than the one before. (…) An hour later, I was sufficiently calm to write these words in a steady hand: God is unjust because he made man incapable of sustaining the effect of coca all life long. I would rather have a life span of ten years with coca than one of 10 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 centuries without coca.” – Like that!

The generic name is of unknown meaning.

Previously, it was believed that it had numerous medicinal properties. In his Herball (1597), English herbalist John Gerard (c. 1545-1612) states the following about it: “A speciall helpe to defend the heart from noysome vapours and from the infection of the plague or pestilence, and all other contagious diseases, for which purpose it is of great effect, the juice thereof being taken in some drink. (…) It is a capital wound herb for all sorts of wounds, both of the head and body, either inward or outward, used either in juice or decoction of the herb, or by the powder of the herb or root.”

In his illustrated herbal Neuwe Kreuterbuch (from 1588), German physician and botanist Jakob Dietrich (1525-1590), also called Jacobus Theodorus, but better known under the name Tabernaemontanus, states that the root is an efficient remedy against the plague.

In the 1600s, in Kanton St. Gallen, Switzerland, most of the population succumbed to the plague. However, one evening a secretive voice from the sky said: “Esset Knoblauch und Bibernelle – dann sterbet ihr nit so schnelle!” (‘Eat garlic and burnet-saxifrage – then you won’t die so fast!’). And in 1832, when cholera claimed many victims in Gaden, Austria, a bird flew out from a forest, landed on a man’s head and screamed: “Essts Granabier und Bibernäl – so sterbts nid so schnäl!” (‘Eat juniper berries and burnet-saxifrage – then you won’t die so fast!’).

Today, leaves and root are used against cough, bladder trouble, and muscle spasms, as an astringent and a diuretic, to relieve flatulence, to promote the flow of bile from the gall bladder, and to stimulate menstrual flow.

The specific name is derived from the Latin saxum (‘rock’) and frangere (‘to break’). It was formerly believed that this plant had the ability to dissolve kidney stones.

In his booklet Chrut und Uchrut (in English called Herbs and Weeds – a useful booklet on medicinal herbs), from 1911, Swiss priest and herbalist Johann Künzle (1857-1945) writes: “(…) the root smells like a billy-goat. For this reason it is also called goat’s root, or boucage in French.” – This word is derived from bouc (‘billy-goat’).

The family name is derived from Ancient Greek apo (‘away’) and kyon (‘dog’), alluding to the toxic dogbane (Cionura erecta), which was formerly utilized to poison dogs.

In his delightful book All about Weeds, American botanist Edwin Spencer (1881-1964) writes about pollination of milkweeds:

“(…) they have one of the most distinct flowers of the plant kingdom. It is made for the purpose of tricking insects in order that cross fertilization may be assured. (…) insects attempting to get nectar from the cups in the flower. There are five of these cups on each flower, and they usually are found hanging mouth downward. They are very smooth, and a foot of the insect that tries to alight on one of them invariably slips off and lands on the slit, which lies between two of the cups. This is exactly what should happen; the very purpose for which the flower was made. In that slit lies the male principle of the flower in such a position that it may never come in contact with the female organ, unless it is pulled out and pulled in again. So the foot of the insect goes into the slit and finds itself caught as if between two tough little wires. If the insect is strong enough, a jerk or two will bring out the foot, and along with it two little bags of pollen, which ride away on the insect’s leg to another flower, where the foot again slips into a slit, but this time carrying the pollen bags (…) right down upon the stigmatic surface of the female organ. There the bags stay, and the pollen in them develops as it should (…). Of course, that same insect leg may come out of the second flower slit with two more bags of pollinia hanging to it like two little saddle bags. (…) it takes a strong leg to do this work, and strong insects are sometimes seen with several bags of pollinia hanging to their legs. If the insect is not strong enough, he pays dearly for the sip of nectar he gets. (…) if he cannot pay for that nectar by carrying away to another flower those two little pollinia bags, he hangs there until he dies (…).”

The generic name is the classical Greek name of the swallow-wort (Vincetoxicum hirundinaria), another member of the dogbane family. The name refers to Asklepios, the Greek god of medicine, son of Apollo and princess Coronis.

According to Kew Bulletin (1897), it has insecticidal properties, being especially obnoxious to fleas. Infected rooms are thoroughly swept with brooms, made from this plant, and the pests are said to disappear. It has also been widely utilized in traditional medicine.

The specific name is derived from Curaçao, a Caribbean island, where the type specimen was collected.

The fruit of one member, the Sodom apple (Calotropis procera), was first described by Roman historian Titus Flavius Josephus, born Yosef ben Matityahu (c. 37-100 A.D.), who found it growing near the city of Sodom: “which fruits have a colour as if they were fit to be eaten, but if you pluck them with your hands, they dissolve into smoke and ashes.” (W. Whiston, 1737. The War of the Jews, Book IV, Chapter 8, Sec. 4). Titus is referring to the fact that the ripe fruit easily dissolves, releasing hundreds of downy seeds, which are scattered to the four winds.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kalos (‘beautiful’) and tropis (‘keel of a ship’), referring to the beauty of the flowers, and to the 5 keel-shaped ridges in the corona.

In India, it is used as an insecticide and fungicide. Bark fibres are utilized for ropes, carpets, fishing nets, and sewing thread. A fermented mixture of giant milkweed and salt is employed to remove the hair from goat skins for production of nari leather. The seed hairs are often stuffed into pillows.

In Nepal, juice of bark and root are taken for diarrhoea and dysentery. Heated leaves can relieve muscular pain. Dried leaves are smoked, the smoke blown out through the nose to relieve sinusitis. Juice of the leaves is taken for fever, and juice of young buds is dripped into the ear for earache. Powdered flowers are used for cough, colds, and asthma. The milky juice, and also a paste of the root, is applied to wounds, sprains, boils, and pimples.

In Ayurvedic medicine, the root bark is regarded as a laxative, as a remedy against fever, and to expel phlegm and intestinal worms. The powdered root is used for asthma, bronchitis, and dyspepsia, the leaves for treatment of paralysis, painful joints, swellings, and fever. The latex is used as a purgative and an emetic.

The flowers are widely utilized as decoration. It is told that Hawaiian Queen Liliuokalani (1838-1917) wore them as a symbol of royalty, strung into leis (garlands).

The specific name refers to its great size. It may grow to 4 m tall.

The inflorescence of these plants is very distinctive, with a large, often brightly coloured blade, the spathe, which encircles a central club-shaped axis, the spadix, on which numerous tiny flowers are clustered, male flowers above, females below. The tip of the spadix often has a flowerless part, the appendage. In some species, spathe and spadix have a thread-like tip, which is sometimes up to 1 m long. In other species, the flowers are foul-smelling, which attracts flies that pollinate the flowers. The fruit is a club-like cluster of berries, remaining on the spadix when the spathe has withered.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek arisamos (‘conspicuous’ or ‘distinguished’), naturally alluding to the spectacular appearance of these plants. A common name of the genus is Jack-in-the-pulpit. To some people, the flower resembles a person in a pulpit: ‘Jack’ is the flowering club, and the ‘pulpit’ is the spathe. Another name is cobra plant, referring to the cobra-like spathe on some species. The Nepalese name of these plants is sarpa ko makai (‘snake maize’), likewise alluding to the cobra-like spathe, and to the cluster of fruits, which resembles a maize cob.

Outside the summer months, fresh vegetables are often difficult to find in rural areas of the Himalaya. A widespread method of obtaining nutrients from vegetables at times, when fresh ones are not available, is to make gundruk – fermented leaves of certain cultivated plants, including cabbage, mustard, and radish, and of various wild plants, including Arisaema utile (below), a large buttercup named Ranunculus diffusus, and Nepalese dock (Rumex nepalensis).

Two methods are utilized to make gundruk. One is to wash the leaves and leave them to dry for a day, after which the last juice is beaten out of them. They are then stuffed firmly into a container, which is tightly closed, making it airtight. About a week later, the fermented leaves are taken out and left to dry in the sun, after which they are stored in a dry place for later use. Another method is to boil the leaves for a short time and then stuff them tightly in a container. After a short period of time, the juice is removed and boiling water added. The leaves are then left to ferment for 4-5 days, before being dried in the sun. (Source: N.P. Manandhar 2002. Plants and People of Nepal. Timber Press)

Gundruk can be kept for about a year. The fermented leaves emit a characteristic fragrance, and they have a unique, strong, and lovely taste – at least in my opinion.

The tuber and ripe fruits of various Himalayan species are also edible after being boiled.

Numerous species of the genus are described on the page Plants: Himalayan flora 1.

It is endemic to Taiwan, growing in forests from the lowland to medium elevations throughout the island.

In 1544, when the Portuguese first saw Taiwan from the sea, they named it Formosa (‘beautiful’). Since then many plants and animals, which were described from specimens collected on the island, were named various forms of this word.

It grows in forests at altitudes between 2,100 and 3,000 m, from Kashmir eastwards to Sikkim.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘size in between’, presumably compared to two other Arisaema species.

This species is widespread and very common in the Himalaya, found in forests and shrubberies at elevations between 1,300 and 3,000 m, from Pakistan eastwards to south-western China.

Locally, ripe fruits are cooked for food, and the corm and fresh fruit are used as an insecticide. In Pakistan, an extract of the rhizome is utilized to expel intestinal worms in cattle.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘twisting’, presumably alluding to the spadix.

The spathe is to 15 cm long, including tube, dark purple with white ribs near the base. The margin is netted with transparent veins, and the apex is notched, with a pointed tip, to 3 cm long. The purple spadix appendage is whip-like, to 22 cm long. The single leaf is trifoliate, with red-margined leaflets, to 25 cm long and 18 cm broad.

This species is much utilized for making gundruk (see above), a fact reflected in the specific name, which means ‘useful’ in the Latin.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek symploce (‘connection’) and karpos (‘fruit’), indicating that the plant has a compound fruit.

Other popular names like clumpfoot cabbage and foetid pothos are not too flattering either, whereas the names swamp cabbage and meadow cabbage refer to its former usage in soups and stews by native tribes. Shamans also used it as a magic talisman.

Later, it was used in the treatment of various respiratory diseases, nervous disorders, rheumatism, and dropsy.

It is native to eastern North America, from Nova Scotia and southern Quebec, westwards to Minnesota and southwards to North Carolina and Tennessee.

In spite of its unpleasant odour, skunk cabbage is praised in a poem, My Fetid Friend, by Joshua Schwartz (born 1976):

The generic name is the classical Latin name of the common ivy (below), stemming from Proto-Indo-European ghed (‘to seize’ or ‘to grasp’). The common name is derived from Old English ifig, ultimately from the German Efeu, of unknown origin.

In his Herball (1597), English herbalist John Gerard (c. 1545-1612) recommends water infused with ivy leaves as a wash for sore or watering eyes. In his Complete Herbal, British herbalist Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654) says: “It is an enemy to the nerves and sinews taken inwardly, but most excellent outwardly.”

In his work The New Family Herbal: Comprising a Description, and the Medical Virtues of British and Foreign Plants, etc., etc., herbalist Matthew Robinson tells us that the flowers decocted in wine restrains dysentery, and that the yellow berries are good for those who spit blood, and also against jaundice.

In Ancient Greek mythology, ivy was dedicated to the wine god Dionysos, symbolizing joy and merriment. His followers adorned themselves with foliage of grape vine and ivy, and poets wore ivy wreaths around their forehead.

In former days, English taverns bore over their doors the sign of an ivy, to indicate the excellence of the liquor supplied in them.

The specific name is Ancient Greek, meaning ‘twisted’ or ‘spiralled’, which of course refers to its climbing habit.

Ginseng has been utilized in traditional medicine for thousands of years. The most popular species are Chinese ginseng (P. ginseng) and American ginseng. The first use of ginseng in Chinese medicine dates back to the famous classic herbal book 神農本草經 (Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing), which was written c. 200 A.D., its origin being attributed to the famous emperor and herbalist Shen Nong, who ruled about 2750 B.C. In this book, it is said: “Ginseng is a tonic to the five viscera, quieting the animal spirits, stabilizing the soul, preventing fear, expelling the vicious energies, brightening the eye, improving vision (…) and prolonging life.”

Today, ginseng is mainly taken for its restorative qualities, improving a poor immune system, increasing physical endurance, and treating chronic infection, diabetes, headache from exhaustion, depression, and, taken with Ginkgo biloba, dementia. It is also widely regarded as an excellent aphrodisiac, being a good remedy for erectile dysfunction, again taken with Ginkgo.

American ginseng was used by several Native American tribes for various ailments, including headache, ear ache, fever, stomach problems, and female infertility, and also as an aphrodisiac. Creeks used it for lung problems, the Chippewa people to prolong the life of a dying person. Among several tribes, it was regarded as a magic herb. Creeks would carry the root to ward off evil spirits.

Today, Chinese ginseng and American ginseng are both extremely rare in the wild, having been seriously over-harvested. American ginseng may even be extinct in the wild state. Both species, however, are widely cultivated, and, therefore, not at risk of becoming extinct.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek pan (‘all’) and akos (‘to cure’), alluding to the many medicinal uses of these herbs. The common name is a corruption of the Chinese word 人參 (ren shen), meaning ‘man-root’, in allusion to the root, which resembles a human torso with two legs (see photo).

Himalayan ginseng is widely used in traditional medicine for a large number of ailments, including nosebleed, intestinal bleeding, stroke, dizziness, and sore throat. The Naga people of north-eastern India take a powder made from the dried root orally to treat heart problems, diabetes, cancer, tuberculosis, and ulcers, and also as an aphrodisiac. They also eat the leaves as a vegetable.

The specific name presumably alludes to the inferior quality of this plant, compared to the true ginseng.

The compound leaves, in most species growing fan-like from the top of the plant, are often very large and decorative. Numerous pictures, depicting palm leaves, may be seen on the page Nature: Nature’s patterns.

The type species of the family is the betel palm (Areca catechu), whose name is derived from a local South Indian name of this species, either from the Tamil areec, or from the Malayalam atekka.

In pre-Columbian North America, saw palmetto fibres were widely traded. The leaves are still used for thatching by several indigenous peoples. The fruit is edible and nutritious and was collected for food by several native tribes. It was also taken as an aphrodisiac. The Seminoles and the Bahamians utilized it to treat poisoning from eating tainted fish.

Saw palmetto fruits have expectorant and soothing properties, and traditionally they have been taken for sore throat, cough, colds, bronchitis, and asthma. Research indicates that they are a good remedy for impotence. The fruits have also been used for migraine headache, chronic pelvic pain, bladder problems, and prostate cancer, but new research has not confirmed that the species is effective in treating any of these medical conditions. It may, however, be effective in treatment of benign enlargement of the prostate.

The generic name honours American botanist Sereno Watson (1826-1892), who joined the Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel. From 1867 to 1872, this survey conducted field work in western United States. Later he became curator of the Gray Herbarium at Harvard University. The popular name refers to the numerous sharp spines on the leaf-stalk.

The inflorescence consists of many individual flowers, called florets, which are grouped densely together to form a flower-like structure, the flowerhead, technically called the capitulum. The flowerhead is surrounded by an involucre, consisting of densely packed green bracts, often erroneously called a calyx. The central disk florets are symmetric, and the corolla is fused into a tube. The outer ray florets are asymmetric, the corolla having one large lobe, which is often erroneously called a petal. In some species, ray florets, or sometimes disk florets, are absent.

In his Herball (1597), English herbalist John Gerard (c. 1545-1612) informs us that during the Trojan War the Greek hero Achilles used yarrow to stop bleeding on wounded soldiers. Hence, the name Achillea was applied to the genus by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778).

Various plants, including yarrow, were found in a 50-60,000-year-old Neanderthal grave in Iraq, perhaps indicating that these plants were used medicinally. (Source: G.P. Shipley & K. Kindscher 2016. Evidence for the Paleoethnobotany of the Neanderthal: A Review of the Literature. hindawi.com/journals/scientifica/2016/8927654)

The name yarrow is a corruption of gearwe, an ancient Anglo-Saxon name for common yarrow (below).

English herbalist John Parkinson (1567-1650) informs us that “if it be put into the nose, assuredly it will stay* the bleeding of it.”

In earlier days, yarrow was dedicated to the Evil One, hence the folk names devil’s nettle, devil’s plaything, and bad man’s plaything. It was also used for divination in spells. In eastern England, where yarrow is called yarroway, a peculiar mode of divination formerly took place with its leaves, with which you would tickle the inside of the nose, while reciting the following lines:

In his Complete Herbal, English herbalist Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654) speaks of yarrow as a profitable herb in cramps, and Parkinson (above) recommends a decoction to be drunk warm for ague (malaria).

Among the Micmac people of north-eastern North America, the stalk was chewed or stewed to induce sweating to break fevers and colds. They also pounded the stalks into a pulp to be applied to wounds, insect and snake bites, sprains, and swelling. Among other American tribes, boils, inflamed eyes, and cracked skin on your hands were bathed in a decoction of this plant. This decoction was drunk against fever, colic, and dyspepsia, and it was considered to be blood cleansing and diuretic. Leaves were stuck into the ears in case of toothache, and boiled leaves were wrapped around arthritic limbs. A decoction of the flowers was used internally for stomach pain, and liver and kidney problems, externally against itching. The root was chewed for colds.

Today, yarrow is utilized to relieve menstrual cramps, for colic and infections, and as a diuretic. It stimulates sweating and reduces fever. In the Orkneys, milfoil tea is drunk to dispel melancholy.

In former days, an ounce of yarrow was sewed up in flannel and placed under the pillow before going to bed. You would then repeat the following words, which would supposedly bring a vision of your future husband or wife:

In Sweden, yarrow was formerly used in beer brewing, hence its popular name jordhumle (‘field hops’). Linnaeus considered beer of this type more intoxicating than beer brewed with hops.

In a Chinese form of divination, hexagrams are generated by throwing sticks, made from yarrow stalks – a random method, using the I Ching, or Book of Changes, consisting of sixty-four hexagrams, each of them six lines, each of which is either yin (dark forces) or yang (light forces).

In his novel Cold Mountain, from 1997, American author Charles Frazier (born 1950) relates an old superstition connected with the leaves of yarrow. If its crushed leaves would emit a sharp smell like falling snow, it was a sure sign that the coming winter was going to be hard.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘thousand-leaved’, referring to the many fine segments of the leaves, hence its popular names milfoil and thousand-weed.

These plants have evolved an ingenious method of protecting themselves from insects. They produce a compound, which interferes with the function of the organ responsible for the secretion of juvenile hormones. This chemical will trigger the next moulting cycle to prematurely develop adult structures and can render most insects sterile if ingested in large enough quantities.

They are widely used medicinally, but ingestion is quite risky, as they may harm your liver. They are also toxic to grazing animals, causing liver lesions.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek a (‘without’) and geras (‘old age’), alluding to the fact that the flowers last for a long period of time.

It is a soft-haired plant, which may grow to 90 cm tall, but is mostly much lower. The flowerheads are bluish or white, to 6 mm across, without ray florets.

The juice of this species is widely used to treat cuts, wounds, and burns, and for its antibacterial properties. In Nepal, a paste of the root, mixed with bark of the tree Schima wallichii, is applied to set dislocated bones. A paste of the leaves is applied to remove thorns from the feet, to boils, and, mixed with several other plants, to snakebites. Crushed leaves are rubbed into the hair to expel lice. A paste of the flowers is used to treat rheumatism, and juice from them is applied to scabies. Juice of the flowers, mixed with tulsi (Ocimum tenuiflorum) and boiled for 10 minutes, is taken for colds and cough.

In Brazil, an infusion of goat-weed is employed to treat colic, colds, fever, diarrhoea, rheumatism, and spasms. In Africa, it is used to treat fever, rheumatism, headache, pneumonia, and colic.

Locally, the plant is used for epilepsy, as an insect repellent, an insecticide and a nematicide. Dried powder of it is applied to wounds, a paste of the leaves to boils, a paste of the root to disrupted bones, and juice of the flowers for rheumatism and scabies. Squeezed leaves are used against head lice.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘resembling Conyza‘, formerly a large genus of composites, which has been merged with the genus Erigeron (fleabanes).

Goat-weed has a number of other popular names, including chickweed, whiteweed, bastard agrimony, and appa grass. In Vietnamese, it is called cứt lợn (‘pig faeces’), because it often grows in dirty areas.

The juice is commonly used to treat cuts, wounds, and burns, and for its antibacterial properties. In Africa, it is used to treat fever, rheumatism, headache, pneumonia, and colic. In India, an extract of the plant has been employed to kill mosquito larvae.

Other common names include flossflower, bluemink, pussy foot, and Mexican paintbrush.

The specific name was given in honour of Scottish surgeon and botanist William Houstoun (c. 1695-1733). In 1729, he sailed for the Caribbean and the Americas, employed as a ship’s surgeon for the South Sea Company. He collected plants in Jamaica, Cuba, Venezuela, and at Vera Cruz, Mexico, sending seeds and plants to Scottish botanist and gardener Philip Miller (1691-1771), who was head gardener at the Chelsea Physic Garden in London. One of the collected plants at Vera Cruz was Mexican blueweed.

After returning to England in 1731, Houstoun was commissioned to undertake a three-year expedition, “for improving botany and agriculture in Georgia.” On the way, he visited Madeira to gather grape plantings. As it turned out, he never completed his mission, as he “died from the heat” shortly after arriving in Jamaica in August 1733.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek arktos (‘bear’), in allusion to the burs, which are somewhat similar to bear claws. Of course the name burdock also refers to the burs, which, when ripe, will attach themselves to any animal fur, sweater, or trousers, which happens to bruise the plant, and dock is a term applied to various plants with large leaves.

One authority states that the specific name stems from the Celtic word llap (‘hand’), alluding to the ‘gripping’ burs. The popular name herrif is derived from two Anglo-Saxon words, haeg (‘hedge’), and reafe (‘robber’), perhaps referring to the vigorous growth of this species. Other folk names include fox’s clote, thorny bur, clot-bur, beggar’s buttons, and cockle buttons.

In his delightful book All about Weeds, American botanist Edwin Spencer (1881-1964) writes about the burs: “Sometimes (a boy) is mean enough to throw a bunch of the burs into the hair of a rival, or even into the hair of the girl he thinks has snubbed him. She who has had this experience needs no technical description of the burdock.”

In the tragedy Troilus and Cressida, by William Shakespeare (1564-1616), Pandarus says: “They are burs, I can tell you, they’ll stick where they are thrown.”

Another Shakespeare tragedy, King Lear, also has a direct reference to this plant:

Khadzhi (Hadji) Murat is the title of a short novel, written by Tolstoy 1896-1904, in which the main character is an Avar rebel from the Caucasus, who, because he wants revenge, enters into a fragile alliance with the Russians, whom he until then has fought against.

In his Complete Herbal, English herbalist Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654) says: “The burdock leaves are cooling and moderately drying, wherby good for old ulcers and sores. (…) The leaves applied to the places troubled with the shrinking in the sinews or arteries give much ease: a juice of the leaves or rather the roots themselves given to drink with old wine, doth wonderfully help the biting of any serpents – the root beaten with a little salt and laid on the place suddenly easeth the pain thereof, and helpeth those that are bit by a mad dog. (…) The seed being drunk in wine 40 days together doth wonderfully help the sciatica: the leaves bruised with the white of an egg and applied to any place burnt with fire, taketh out the fire, gives sudden ease and heals it up afterwards. (…) The root may be preserved with sugar for consumption, stone and the lax. The seed is much commended to break the stone, and is often used with other seeds and things for that purpose.”

Traditionally, in many countries, farmers have applied bruised leaves as a remedy for hysteria. Among American natives, a decoction of the root of a near relative, the lesser burdock (Arctium minus), was drunk for whooping cough and arthritis. It was considered to be sweat-inducing and blood cleansing, and also a diuretic.

In modern herbal medicine, root and seeds are used for boils, scurvy, psoriasis, rheumatism, and arthritis. The leaves are applied externally as a poultice for tumours, gouty swellings, bruises, ulcers, and inflammation, and an infusion of the leaves is used for indigestion. Burdock is also utilized for seborrhea, which causes dandruff, and it is regarded as one of the best blood purifiers. Research indicates that it may inhibit attack of HIV virus.

In Nepal, the root is utilized as a diuretic and diaphoretic, and juice of the plant is applied to boils.

Burdock roots are edible, with a sweet and mucilaginous taste. They are much utilized in Chinese cuisine. The stalk is also edible. After removing the rind and boiling the stalk, it tastes like asparagus. However, it is highly laxative, so only small amounts can be enjoyed.

One authority states that the specific name stems from the Celtic word llap (‘hand’), alluding to the ‘gripping’ burs. The popular name herrif is derived from two Anglo-Saxon words, haeg (‘hedge’), and reafe (‘robber’), perhaps referring to the vigorous growth of this species. Other folk names include fox’s clote, thorny bur, clot-bur, beggar’s buttons, and cockle buttons.

The generic name may be derived from Ancient Greek arni ('lamb'), alluding to the soft, hairy leaves of these plants.

In his illustrated herbal Neuwe Kreuterbuch (from 1588), German physician and botanist Jakob Dietrich (1525-1590), also called Jacobus Theodorus, but better known under the name Tabernaemontanus and often called ’the father of German botany’, describes the usage of arnica to treat bleeding: ”In Sachsen, common people use arnica, when they fall down from a high place, or are otherwise hurt during work. You take a handful [of flowers], boil them in beer and drink this concoction in the morning, whereupon you cover yourself to sweat. Where you were hurt feels great pain for two or three hours, but then you are cured.”

In Denmark, arnica was much utilized in the 1700s. In an herbal book, it is said that it has dissolving and neurotonic properties, and another source mentions that a decoction of the plant, drunk with beer, can be used for headache, pressure on the chest, and pains in arms and legs. Arnica flower tea was used as a laxative.

In another herbal from the 1700s, it is said that the flower, laid on an aching tooth, would cause ‘the worms’ to fall out. Danish herbalist Laust Glavind (died 1891) recommended a decoction of arnica and linseed in beer for insanity. As late as in the 1920s, herbal tea with arnica was drunk by women in northern Jutland to treat sterility.

To prevent hair loss, the scalp was bathed in beer, boiled with arnica root, and the label on an Austrian remedy for growth of hair, Quinar, states the following: “Substances are extracted from the flowers, which in an effective way will make your hair bouffant, luxuriant, and beautiful. For centuries, these substances have been known as life-giving for hair growth. Dissolved in alcohol, with added quinine, they form the most important ingredients in Quinar.”

In modern herbal medicine, arnica is regarded as a stimulant and diuretic, chiefly used for low fever and paralysis. It is excellent for shock. Arnica oil is a good remedy for bruises and sprains, but it should not be applied to open wounds. It is also used for insect bites, arthritis, muscle and cartilage pain, chapped lips, and acne.

The leaves were formerly utilized as a substitute for tobacco – hence the name mountain tobacco. Today, an extract of the plant is used for flavouring beverages, frozen dairy desserts, candy, baked goods, gelatin, and puddings, and also as an ingredient in hair tonics and anti-dandruff remedies. The oil is used in perfumes and cosmetics.

In Germany, much superstion was formerly connected with arnica. Placed under the roof, in the living room, in the window, or at the edge of fields, it would ward off lightening strikes, hail, and witches. During thunder, you should burn dried arnica while saying the following rhyme: “Steckt Arnica an, steckt Arnica an, dass sich das Wetter scheiden kann” (‘Ignite arnica, ignite arnica, so that the storm may go away’).

A German folk name of arnica is Wohlverleih, by many authorities translated as ‘endowed with good’, referring to its usage as a medical herb. This interpretation is discarded by German botanist Helmut Gams (1893-1976) in the book Alpenflora – farbige Wunder (‘Alpine Flowers – Colourful Wonder’, 1963), claiming that it stems from the Middle Age names Wolverlei and Wolfesgelegena, which refer to the wolf (Wolf in German), alluding to the great toxicity of the plant. The latter name was used by the well-known German Benedictine nun Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179), a multifarious genius, who was a philosopher, mystic, visionary, herbalist, and composer.

The folk name leopard’s bane also refers to its great toxicity.

The specific name is not very appropriate, as the plant also grows in lowlands.

The genus is named for Artemis, the Greek goddess of wilderness and wild animals, hunting, childbirth and virginity, protector of young girls, and also bringer and reliever of disease in women. In his Herbarium, Roman philosopher and scholar Lucius Apuleius (c. 124-170 A.D.) writes: “Of these worts that we name Artemisia, it is said that Diana found them and delivered their powers and leechdom to Chiron the Centaur, who first from these worts set forth a leechdom, and he named these worts from the Greek name of Diana, Artemis.”

Numerous Asian species of the genus are utilized medicinally. Among certain American tribes, tea made from leaves and flowerheads of mugwort (A. vulgaris) was taken as a stomachic, to calm the nerves, and to reduce fever. It was also drunk in case of menstrual problems, and to expel intestinal worms. – Mugwort is described on the page Plants: Urban plant life.

It held a high reputation among herbalists in Ancient Greece and Rome, according to whom it would counteract the effects of poisoning by hemlock (Conium maculatum, see Apiaceae above), toadstools, and the biting of the sea dragon.

During the Middle Ages, in the Nordic countries, wormwood was used for all sorts of ailments and diseases. In 1546, Danish herbalist Henrik Smid notes: ”Where is the person who can explain all the virtues of wormwood?”

In his compendium The Vegetable System, English botanist John Hill (c. 1714-1775) says: “The leaves have been commonly used, but the flowery tops are the right part. These, made into a light infusion, strengthen digestion, correct acidities, and supply the place of gall, where, as in many constitutions, that is deficient. (…) In the morning, the clear liquor with two spoonfuls of wine should be taken at three draughts, an hour and a half distance from one another. Whoever will do this regularly for a week, will have no sickness after meals, will feel none of that fulness so frequent from indigestion, and wind will be no more troublesome; if afterwards, he will take but a fourth part of this each day, the benefit will be lasting.’”

In modern herbal medicine, common wormwood is used as a tonic, stomachic, febrifuge, and as an anthelmintic. It is also a good remedy for indigestion, debility, and gall bladder infection. As a nervine tonic, it is particularly helpful against epilepsy and for flatulence.

The common name green ginger was given in allusion to the medicinal properties, comparable with those of ginger (Zingiber officinale, see Zingiberaceae below).

Since the Middle Ages, the plant has been utilized to get rid of lice and fleas. It was strewn in bedrooms and placed among clothes and furs to keep away moths. In corn lofts, ‘worms’ and snout beetles were exterminated with wormwood, and smoke from the burning herb would keep flies and mosquitos at bay.

In July’s Husbandry, from 1577, English poet and farmer Thomas Tusser (1524-1580) says:

An old proverb says: “As bitter as wormwood,” and all members of the genus are remarkable for their extreme bitterness. For hundreds of years, common wormwood has been added to alcohol, and still today, two alcoholic drinks in southern Europe, vermouth and absinthe, are spiked with wormwood. However, absinthe is addictive, in large quantities even deadly.

Today, wormwood is cultivated as an ornamental, and it can also be utilized for dyeing, producing yellow colours.

The specific name is the classical Greek name of the plant.

In his Complete Herbal, English herbalist Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654) says about this plant: “Boiling water poured upon it produces an excellent stomachic infusion, but the best way is taking it in a tincture made with brandy. Hysteric complaints have been completely cured by the constant use of this tincture. In the scurvy and in the hypochondriacal disorders of studious, sedentary men, few things have a greater effect: for these it is best in strong infusion. The whole blood and all the juices of the body are effected by taking this herb.”

Dr. Hill (see above) states: “This is a very noble bitter. Its peculiar province is to give an appetite, as that of the common wormwood is to assist digestion. The flowery tops and the young shoots possess the virtue, the older leaves and the stalk should be thrown away as useless. (…) The apothecaries put three times as much sugar as of the ingredient in their conserves; but the virtue is lost in the sweetness, those will not keep so well that have less sugar, but ’tis easy to make them fresh as they are wanted.”

An old proverb says: “As bitter as wormwood,” and for hundreds of years, sea wormwood has been added to alcohol in the Nordic countries.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘found at the sea’.

The generic name is derived from the Latin bi (’two’) and dens (’tooth’), alluding to the mostly 2 (sometimes 3 or 4) sharp, hooked teeth on the seeds, which easily get attached to animal pelts or people’s clothes, hereby often being spread a considerable distance from the mother plant. This way of seed dispersal has given rise to names like beggar-ticks, stickseed, farmer’s friend (sic!), needle grass, Spanish needles, stick-tight, cobbler’s pegs, Devil’s needles, and Devil’s pitchfork.

It is quite common, but less common than the trifid bur-marigold (below). It is larger than that species, to about 1 m tall, has undivided leaves and rather large, sunflower-like flowers. It is partial to wet areas, especially along lake sides.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘bent forward’, referring to the nodding flowers.

A South African website, farmersweekly.co.za/animals/horses/beware-those-blackjacks, says: “The common blackjack is not only an irritant to horses, (but) can cause them injury. (…) There can be few of us who have not spent ages picking them off our clothes after walking through the veld to catch horses in the early winter. Blackjacks that become entangled in the forelock of a horse can be a great irritant, and the animal will toss its head, if you try to remove them. The spines can injure the eyes, so it’s better to clip the forelocks short. Blackjacks can also get caught up in the long hair behind the fetlocks and pasterns, causing chronic irritation and lameness.”

This species is reported to be a weed of 31 crops in more than 40 countries, Latin America and eastern Africa having the worst infestations. (Source: cabi.org/isc/datasheet/9148)

However, downy bur-marigold is not only a troublesome weed, it also has medicinal properties. In traditional Chinese medicine, it has been used for a large number of ailments, including influenza, colds, fever, sore throat, appendicitis, hepatitis, malaria, and haemorrhoids. Due to its high content of fiber, it is beneficial to the cardiovascular system, and it has been used with success in treatment of diabetes.

The specific name is derived from the Latin pilus (‘hair’) and osus (‘full of’, ‘plenty’), thus ‘very hairy – not a suitable name, as the plant is not particularly hairy.

Other pictures of this species are shown on the pages Plants: Urban plant life, and Nature: Invasive species.

Formerly, it was much utilized in traditional medicine to treat bleeding, particularly blood in the urine. The plant is astringent and diuretic, and was used against fever, to stimulate menstruation, to relieve constipation, to induce sweating, and as a sedative.

Young leaves are edible when cooked.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘trifid’, alluding to the leaves, which often have 3 lobes.

The generic name is possibly derived from keksher, a word of Egyptian origin.

Chicory was cultivated in Ancient Egypt and was utilized medicinally from at least the 1st Century A.D. The Egyptians, as well as the Greeks and the Romans, considered the bitter leaves to be blood cleansing, and to invigorate the nerves. Other old herbalists recommended the leaves, when bruised, as a good poultice for swellings, inflammations and inflamed eyes, and that “when boiled in broth for those that have hot, weak and feeble stomachs doe strengthen the same.”

English poet and farmer Thomas Tusser (1524-1580) considered chicory a useful remedy for ague (malaria), and herbalist John Parkinson (1567-1650) found it to be a “fine, cleansing, jovial plant.”

In the 16th and 17th Centuries, followers of the Doctrine of Signatures took it for granted that the milky juice of the plant would be a good remedy for sore breasts of nursing mothers, whereas its bright blue flowerheads symbolized blue eyes and would thus be an effective remedy for inflammation of the eyes.

Today, herbalists recommend chicory as a stomachic and diuretic, and as a blood purifier. It also stimulates the heart and liver. The root is widely used to expel intestinal worms and other parasites.

The flowerheads of chicory unfold in the morning, and until around noon they turn, always pointing toward the sun, after which they wither. A German name of the plant is Wegwarte (’waiting at the road’). A legend has it that chicory is a transformed virgin, standing at the road side, looking for her sweetheart, turning this way and that.

The Ancient Egyptians, Arabs and Romans ate the leaves as a vegetable or in salads. Today, young leaves of cultivated forms are still eaten in salads, but they are generally blanched, as this removes the bitterness of the leaves. The French call blanched leaves barbe de capuchin (‘Capuchin monk’s beard’) – a favourite winter salad.

It has been suggested that a common name of the plant, succory, stems from the Latin succurrere (‘to run under’), referring to its long root. However, it may be a mere corruption of the generic name. Hendibeh is the Arabic name of a near relative, endive (C. endivia), and the specific name is a corruption of this word.

Naturally, the common names blue sailors, ragged sailors, blue daisy, blue dandelion, and blue weed all refer to the pretty blue flowerheads, whereas the name coffee weed refers to the earlier usage of the root, which, dried and pounded, was widely utilized as a substitute for coffee, but this usage has largely disappeared.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of elecampane (below), derived from Ancient Greek inaein (‘cleansing’), referring to its medicinal properties. The common name refers to the large, showy, yellow flowerheads of many members.

Several species that were previously placed in this genus, have been transferred to the genus Pentanema.

This plant has been used medicinally for at least 2000 years, first mentioned in Codex Constantinopolitanus in 512 A.D.

In his Complete Herbal, English herbalist Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654) states: “The fresh roots of Elecampane preserved with sugar, or made into a syrup or conserve, are very effectual to warm a cold windy stomach, or the pricking therein, and stitches in the sides caused by the spleen; and to help the cough, shortness of breath, and wheezing in the lungs. The dried root made into powder, and mixed with sugar, and taken, serveth to the same purpose; and is also profitable for those who have their urine stopped, or the stopping of women’s courses, the pains of the mother, and of the stone in the reins, kidnies, or bladder (…) The root boiled well in vinegar, beaten afterwards, and made into an ointment with hog’s suet, or oil of trotters, is an excellent remedy for scabs or itch in young and old; the places also bathed or washed with the decoction, doth the same (…)”

Elecampane was also used for tuberculosis.

Even today, many herbalists consider this herb an effective remedy for lung problems, such as congested phlegm, bronchitis and emphysema (swollen alveoles). It has a beneficial effect on digestion. It is also used to expel intestinal worms and other parasites.

To the Celts of Britain, elecampane was a sacred plant.

In the 1500s, elecampane roots were sweetened and eaten as candy in England. Today, in France and Switzerland, an extract from the root is added as flavouring to absinthe, an alcoholic drink. It is widely cultivated as an ornamental.

In the 5th Century, the plant was called Inula campana, in medieval times Enula campana, which, by the English, was corrupted to elecampane. The specific name, derived from Ancient Greek helenion, was first mentioned by Greek scholar and botanist Theophrastos (c. 371 – c. 287 B.C.), called ‘the founder of botany’. Later a physician, Nikander (c. 147-? B.C.), linked the name with Helen of Troy. One legend has it that elecampane sprang from Helen’s tears, falling on the ground, when she was abducted by Prince Paris.

The popular names horseheal and horse elder were given in allusion to an old custom in Britain, where asthmatic horses were fed with the fleshy root of elecampane. The name scabwort refers to its former usage to treat scabies.

The very similar Inula racemosa of Central Asia is widely used as an expectorant. It is described on the page Plants: Himalayan flora 1.

The generic name is derived from the Latin matricis (’mother’s life’, i.e. the womb). Formerly another plant, feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium, see below), was regarded as a species of chamomile, named Matricaria parthenium by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778). In Ancient Rome, feverfew was used for uterus problems.

The flowerheads are collected and dried to be used as tea, which is a very efficient remedy for colds, sore throat, mouth ulcers, stomach ache, and colic. It is used for many other problems, such as allergies, diverticulitis (abdominal pain), fungal infections, insomnia, and heartburn, and also as a diuretic and a diaphoretic. Chamomile soothes inflammation, cramps, and menstrual pain. Externally, it is used for skin problems, including eczema, and for ulcers and burns, and a tincture is used to keep biting insects at bay.

In former days, chamomile was one of the commonest medicinal herbs, utilized for many diseases, including bladder stones, flatulence, chest pain, tooth ache, bite of a mad dog, ‘heated brain’ (migraine?), bad nerves, etc.

In Denmark, in the old days, a number of superstitions were connected with chamomile. When a woman passed a growth of chamomile, she had to make a curtsy twice. On Midsummer’s Eve, the girls would adorn their chamber with chamomile flowers, and on the island of Falster, it was placed among the plates on their rack. On Sunday morning, chamomile flowers were burned to spread fragrance in the living room. In the 1600s, on 24th of June, chamomile and burdock (Arctium lappa, see above) were placed several places in the house as protection against the poison, which in the evening would surge up from the earth.

Formerly, boys would smoke dried chamomille flowers as tobacco. If you rinsed your hair in chamomile water, it would get a sheen. Chamomile and wormwood (Artemisia absinthium, see above) were added to beer to make it keep. (The honour probably goes to wormwood, whereas chamomile might have added fragrance.)

Today, an essential oil, derived from the flowers, is utilized cosmetically.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek chamaimelon, meaning ‘earth-apple’, referring to the apple-like scent of German chamomile.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek petasos, meaning ’a broad-brimmed hat’, which, like the common name umbrella plant, refers to the large leaves of many species, sometimes growing to 1 m across. The common name supposedly stems from the habit of using the large leaves to wrap around butter in hot weather, while another popular name, lagwort, refers to the late appearance of the leaves, which do not usually unfold, until the flowers have faded. ‘Dock’ is a term applied to various plants with large leaves, for these plants used in the popular names flapperdock, blatterdock, and butterdock.

It has both male and female plants, and female plants were given the name Tussilago hybrida by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), as he thought they were a hybrid between the male plants and white butterbur (Petasites albus). In northern Europe, female plants are very rare, and almost all populations are clones of male plants.